Summary of British Art

Whereas Italy (the Renaissance) France (Impressionism) or America (Abstract Expressionism) have provided clearly defined national schools, the development of British art has tended to be more splintered and therefore more difficult to place within the historical trajectory of world art.

Though their global influence might not have reached the heights of the aforementioned movements, one might argue with a degree of justification that the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood or YBAs (Young British Artists) qualify as "quintessentially British" movements. It is also true that Britain has produced a number of internationally renowned artists working across a broad range of styles - names like Turner, Constable, Hepworth, Freud and Hockney come easily to mind - but, though affiliated with specific movements (Romanticism, Surrealism, School of London and Pop Art), they tend to be thought of as exceptional individuals rather than figures who carried the torch for a particular cadre or school. Moving into the 21st century, meanwhile, the Street artist Banksy and the annual Turner Prize continue to represent Britain at the cutting-edge of the contemporary international art scene.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The story of Britain can be traced back through its art over 500 years and more. A country that prides itself on its heritage, and the tenets of democratic and personal freedom, its art - from Gower to Hogarth; Holman Hunt to Cameron; Francis Bacon to Emin - represents the full creative ebb-and-flow of the nation's stately and libertarian traditions.

- A rain-swept island state, and still thought of fondly (thanks in no small part, no doubt, to William Blake's poetry) as a "green and pleasant land", Britain was in fact at the forefront of the seventeenth-century age of scientific reason and industrialization. The early period of "enlightenment" provided a strong creative backdrop for British art giving rise on the one hand to the exact equine paintings of George Stubbs, and on the other, the biting social satire of William Hogarth.

- The age of objective reason brought with it its dissenters and the "romantics" are amongst Britain's greatest internationally recognized artists. The first to explore the links between forces of nature, poetry and art, William Blake opened a door for two icons of British art, John Constable and J.M.W. Turner, who between them effectively "reinvented" the British rural and industrial landscape and whose influence carried far across Europe and North America.

- From the ruins of two world wars, Britain was delivered into the global age through 1950s British Pop Art. Since "swinging" London vied with New York as the epicentre of 1960s world culture, British art has continued to keep pace - through Conceptualism, Minimalism, the revival of the figure, and the iconoclasm of YBA - with the insistent march of postmodernism.

Overview of British Art

Pop Art is thought to have originated in the USA, but in fact, it was born in the UK. A closer look at art from this small nation reveals many more surprises. "The Shark" is just one example how British Art is so central in the contemporary creative world.

The Important Artists and Works of British Art

The Wilton Diptych

This devotional piece has been described as the "most beautiful dream of heaven to survive in all British art". The work was created as a portable altarpiece for Richard II, who ruled England from 1377 to 1399. Named after Wilton House in Wiltshire, where it was housed for more than two centuries, the diptych depicts Richard II kneeling and robed in anticipation of holding the Christ Child. Behind him stand Saint John the Baptist, Saint Edward the Confessor and Saint Edmund. The work is finely adorned, with golden crowns, finery and gowns. The right panel shows the Virgin Mary holding the outstretched Jesus as she hands him to the king. Mary is surrounded by eleven winged angels in blue, standing amid flowers. The work is rich with symbolism: St George's flag flies in the background; the white harts pinned to the angels' gowns act as the king's badge; and the rosemary of the grassy meadow is thought to be presented in remembrance of Richard's dead wife, Anne of Bohemia.

The work is most significant because it stands alone in the canon of early art history, argued art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon, and it marks the point at which the nation cut itself off from the continent. The reformation saw England isolated from the rest of Europe, artistically as well as politically. Indeed, The Wilton Diptych is the lone British piece in the Renaissance wing of the National Gallery. As Graham-Dixon, noted it "hangs among Sienese paintings of the fourteenths and fifteenth centuries and it is the only British painting in this section [...] There was to be no British Titian, no Tintoretto, no Raphael, no Michelangelo, no Caravaggio, no Velázquez."

Egg tempera on oak panels - The National Gallery, London

Mr and Mrs Andrews

In a sunny patch beneath an oak tree, a couple sits informally for a painting celebrating their marriage. Behind them stretches the English countryside, with well-managed farmland and hills beyond. The work acts as a triple portrait, showing not just Robert Andrews and his new wife Frances, but their sprawling 3,000-acre estate.

The Rococo influence can be seen in the ornate curvature of the bench on which Mrs Andrews sits and the couple's status as wealthy landowners can be seen in their fine clothing. And while landscape painting was not given the status of history painting, Reynolds used his technical excellence in his depiction of the Essex countryside so as to emphasize the painting's "Englishness". The row of corn, which would not have likely existed so close to the sitters' location, symbolized harmony between humankind and nature, and the fertility of land - an important factor in a marriage portrait.

A leading portraitist, Joshua Reynolds believed that the Italian Renaissance masters were the brave men of art, and he sought to bring the lessons of their technical excellence into British painting. Indeed, his works mimicked the grand Renaissance style and brought a new gravity to society portraiture. As art historian Wendy Beckett noted: "Reynolds, as befitted a poor boy, responded enthusiastically to the romance of the British aristocracy. He understood the need of upper-class personages - frequently undistinguished in either intellect or appearance - to seem far more interesting than they actually were."

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, London

The Rake in Bedlam

This is the final work in an eight-part cautionary tale series about the demise of the fictional Tom Rakewell, a hapless and greedy young man who has come to London to find his fortune. The plates tell the story of how this arrogant man who thought he could become a member of the aristocracy squandered all his money on drinking, prostitution and gambling, and ended up in debtors' prison and finally Bethlem Hospital (or "Bedlam") a notorious mental asylum. The protagonist lies in the front of the frame, shackled at the ankle, bald and denuded of the fine clothes he had been trying on in plate I. Surrounding him are other patients, ghoulish in their hallucinations to highlight Tom's own delusions of grandeur that brought him down. The walls, covered in art in previous plates, here are unadorned and gloomy, as light from the denied world streams through barred windows. In William Hogarth's times, members of the aristocracy were permitted into such institutions to gawp at the victims for their own amusement. This finale sees two finely-dressed women looking on and whispering in gruesome delight at the stricken Tom.

A portraitist and history painter, Englishman Hogarth's work was groundbreaking in a number of ways. It was he who first created the idea of a British school (of art), he was one of the first self-made artists (producing works independently of direct patronage) and he was considered the creator of satire. His work held up a mirror to a rapidly-changing England and all the social ills that were the downside of industrialization. Previously, lessons in art came from religious teaching, but Hogarth's modern moral tales had important messages for the public about greed, excess, and hypocrisy.

Oil on canvas - Sir John Soane's Museum, London

The Market Cart

Born in Sudbury, Suffolk, Gainsborough trained in London before setting up his practice in Ipswich. He later moved to the spa town of Bath where he attracted many fashionable clients seeking portraits. A great admirer of Anthony Van Dyck and Peter Paul Rubens, Gainsborough continued to paint landscapes (it is estimated that he produced some 200 in total) though many of these were produced from the memory of his rural Suffolk origins.

A founding, if somewhat indifferent, member of the Royal Academy (and favorite painter of King George III), Gainsborough was considered, with his competitor Joshua Reynolds, the leading portraitist in late 18th century England but both men made important contributions to British landscape painting. Speaking of his great rival, Reynolds was generous in his praise for his more instinctive, "less academic," colleague: "If Gainsborough did not look at nature with a poet's eye [as Reynolds had] it must be acknowledged that he saw her [nature] with the eye of a painter; and gave a faithful, if not poetical, representation of what he had before him." Indeed, according to Rothenstein, when compared to Reynolds, Gainsborough's landscapes were considered by many of his contemporaries to be positively realist.

The Market Cart belongs to Gainsborough's mature period (it was completed two years before his death) when his work had become more nostalgic. He was engaged in the creation of a "credible" Arcadia; that is an Arcadia comprised of two elements: observation and poetry that, when combined, would produce a kind of "material paradise". His later landscapes featured a series of pictures of peasant life that were generally more ideal than real, but The Market Cart came much closer to his version of a "material paradise" and in fact looks forward towards Constable in its treatment of breaking light and overwhelming foliage. Indeed, commenting on Gainsborough's landscapes, Constable said: "The stillness of noon, the depths of twilight, and the dews and pearls of morning, are all to be found on the canvases of this most benevolent and kind-hearted man. On looking at them we find tears in our eyes, and know not what brings them." It was a view supported by Rothenstein who argued that Gainsborough had ultimately produced "An Arcadia so touching in its beauty that it has never ceased to haunt the English imagination."

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, London

Beatrice addressing Dante from the Car

All but unknown in his own lifetime - he was buried in a pauper's grave, and even those who were acquainted with him thought him mad - William Blake, painter, poet, draughtsman and printmaker, has assumed an illustrious position in the history of British art. A bona-fide radical whose personal, spiritual and expressive language proved inspirational for future generations of artists - especially the Romantics - many would argue that he is perhaps, if not the most technically gifted, then certainly amongst the most original, of all the great English artists. Blake developed a visual language all of his own but he remained mindful of the fact that his work should possess a clarity that could communicate his heart-felt spiritualism to the lay spectator or reader.

Confirming his distaste for formal art education and the likes of "academics" such as Joshua Reynolds, Blake declared "Men think they can copy nature [but] they will find this impossible, and all the copies of nature proves that nature becomes to its victims nothing but blots and blurs". His view was then that the power of imagination was the greatest artistic tool and he painted free, as much as that is possible, from the chains of convention. As such, Blake preferred to bring the written word to life by illustrating stories including those from the Bible, Milton and Dante.

Commissioned by John Linnell, Blake produced a total of 102 illustrations (most of them left incomplete due to ill health and his subsequent passing) that brought his own Christian interpretation to Dante Alighieri's epic fourteenth century poem The Divine Comedy. In this watercolor, for instance, he imagines the end of The Divine Comedy where Dante is led to paradise (through the gates of heaven) by Beatrice, the earthly (rather than divine) personification of Vala, the Goddess of nature. Beatrice is flanked by the four apostles, here represented by Blake through Christian symbolism: Luke resembles an ox; Mark appears as a lion; John with the face of an eagle while Matthew is shown as a man who resembles Christ himself. Blake also uses color to promote the idea that beauty exists in the natural world rather than in the divine and now that Dante comes to this realization he can enter into paradise.

The Palace of Westminster

The Houses of Parliament, otherwise known as the Palace of Westminster, is possibly London's most iconic landmark and a symbol of Great Britain and its proud parliamentary democracy. The central block of the Palace is skirted by two towers: the Victoria Tower (which at 325 feet was thought to be the tallest square stone tower in the world) served originally as a royal entrance and as an archive for parliamentary records, and the Elizabeth Tower - known colloquially as "Big Ben" after its famous bell - which overlooks Westminster Bridge and Parliament Square. The Palace, and the neighbouring Westminster Abbey and St. Margaret's Church, are classified as UNESCO World Heritage sites while the palace itself is a grade 1 listed building.

The original Palace was built during the eleventh century when it was the official residence of the Kings of England until it was destroyed by fire in 1512. The Palace was duly rebuilt and became the seat of English law. This move was necessitated somewhat by the rule of Henry VIII, whose break with the holy church of Rome, and his various divorces (which threw the succession to the throne into confusion) caused constitutional chaos. The current building replaced the timber-framed parliament building when it too burnt to the ground in 1834. Considered the worst fire since the Great Fire of London, only the Jewel Tower, the medieval Hall, cloister and the Chapel of St Mary Undercroft were spared.

Charles Barry (he had estimated a six-year construction period that eventually took 30 years at a cost of over two million pounds) won the competition to design the new Palace having proposed a complex of buildings - reclaiming some eight acres of land from the river Thames - in the Gothic style while incorporating the surviving medieval buildings. The perpendicular structure is home to some 1100 rooms, positioned around two courtyards and Barry was preoccupied with bringing a harmony between the horizontal bands of the panelling and the vertical turrets that rose above the walls. He is also credited with introducing steeply-pitched iron roofs which made a special feature of the Palace's skyline. Barry was aided by A. W. Pugin who deserves the best part of the credit for the sumptuous exterior and interior Gothic detail. It is he who extended Barry's decorative Gothic scheme to interior furnishings - such as wallpaper, carvings and stained glass - and its various thrones and canopies. Sadly, both men died before the Palace was completed.

Rain, Steam, and Speed - The Great Western Railway

In contrast to his contemporary, John Constable, Turner's take on Romanticism is expressed in his fondness for symbols of the industrial age, and their relationship to nature. In this acknowledged masterpiece, we see Brunel's Maidenhead railway bridge emerging from the mist as a locomotive thunders towards us. Beneath the bridge runs the River Thames as it courses eastwards towards London. A lone boatman drifts in the water, his stillness at odds with the noise and speed of the oncoming train. The drama and power of this work echoes the change seen by the era: the locomotive rushes towards us from the swirling mists and vapor: Victorian Britain is witnessing irreversible changes to its industry and landscape. This work was produced just two decades after Constable's The Hay Wain, but, in a sense, they are an age apart.

The theory of "the sublime" in art was proposed in 1757 by British stateman and philosopher Edmund Burke in his book A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. Burke defined the sublime in art in terms of works that could evoke the very strongest emotions in the spectator: "whatever is in any sort terrible or is conversant about terrible objects or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime" he wrote. This work shows Turner's exploration of the sublime, as foreboding notions of speed, time, change and progress are mixed with Turner's flamboyant brush strokes. Its striking effect (which caused discontent amongst Academy members) was alluded to by art historian E.H.Gombrich who noted: "In Turner, nature always reflects and expresses man's emotions. We feel small and overwhelmed in the face of the powers we cannot control, and are compelled to admire the artist who had nature's forces at his command." It was Turner's study of architecture and industry that proved him to be a true pioneer. As historian Andrew Graham-Dixon put it: "Turner did not just predict modern art. He anticipated at least some of the poetry and adventure, and uncertain, speculative beauty of modern science". Indeed, some of Turner's landscapes could be seen as precursors for abstract art given that he was willing to transform the familiar by altering the light and scale of his compositions.

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, London

Mother and Child

Between 1920-21 Hepworth and her colleague Henry Moore both studied at art college in Leeds before moving to the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Having formed a close working friendship with Moore, Pablo Picasso, Constantin Brancusi, and later with a host of other European avant-gardists, Hepworth would (like Moore) become a world leader in avant-garde sculpture. She (like Moore) is chiefly associated with the practice, pioneered by Brancusi in 1906, of Direct Carving, a process whereby the sculptor works without preparatory models and maquettes (which would then be constructed, at the sculptor's behest, by artisans). Both Hepworth and Moore were interested in primitivism and drew inspiration from objects on display at the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Hepworth indeed owned several ancient artefacts, including some of Neolithic and Cycladic origin.

Predating her career defining move to St Ives, Hepworth made Mother and Child in her London studio in 1934. By now Hepworth was in a romantic relationship with the abstract painter Ben Nicholson and with whom she developed a symbiotic working relationship. But what might have been thought of as a truly abstract piece - the small stone sculpture is a horizontal configuration using undulating and biomorphic shapes - Hepworth gives Mother and Child figurative form through the nodule like "heads" and, of course, the descriptive title.

We can thus discern that the mother reclines while supporting her "pebble" child on her lap and the opening (the negative space) that draws our eye to the centre of the work acts to denote the shape of the mother's arm that rest on the leg supporting her child. It is possible that the negative space (a concept that Hepworth pioneered) also carries a conceptual value in that it connotes the child's removal/separation from the mother's womb. It appears, moreover, that the couple are independent sculptural elements but they were in fact carved from a single piece of brownish-grey Cumberland alabaster while the piece itself sits on a thin rectangular base.

Cumberland Alabaster - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

War Child: Portrait of a Young Victim of the Blitz. Three-year-old Eileen Dunne, a victim of the London Blitz, in hospital

The English photographer Cecil Beaton might be considered something of a 20th-century Renaissance man. Best known, of course, for his fashion photography and his high society portraits, Beaton's sophisticated portraiture earned him the role of unofficial court photographer of the British royal family. His standing was such that in 1937 he took the wedding portraits of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and in 1953 he shot Queen Elizabeth II's official coronation portrait against a backdrop of Westminster Abbey. Beaton also won four Tony Awards and three Oscars for costume design and art direction. He is less well-known however for his war photography in which he covered the conflict in England, the Near East, Far East and India, for the Ministry of Information. Beaton was in fact an accomplished war photographer, producing some of the most enduring images of the conflict.

Beaton's 1940 portrait of Eileen Dunne, a bandaged 3-year-old victim of the blitz, was a breathtaking piece of propaganda that, by featuring on the cover of LIFE magazine, encouraged America to take a keener interest in the war in Europe and drew special attention to Britain's defiance of the Third Reich. The portrait repeats the elegant and sympathetic touch that Beaton brought to his portraits of the British royal family. LIFE introduced the portrait thus:

The wide-eyed young lady on the cover is Eileen Dunne, aged 3 3/4. A German bomber whose crew had never met her dropped a bomb on a North England village. A splinter from it hit Eileen. She is sitting in the hospital. A plucky chorus of wounded children had just finished singing in the North English dialect, "Roon, Rabbit, Roon." The picture was taken by Cecil Beaton, the English photographer who generally specializes in fashionable or surrealist studies of society women.

Gelatin silver print - Imperial War Museum collection, London

Lancashire Fair, Good Friday, Daisy Nook

Though he has divided critical opinion it would be remiss in a history of mid-twentieth century British art to overlook the contribution of L. S. Lowry. In 1976, shortly after his death, for instance, a comprehensive retrospective exhibition of his work at the Royal Academy saw some hail him as a significant artist with a unique vision while others dismissed him as a minor talent and only of interest as a social commentator.

Lowry lived all his life in or near Salford, in industrial Northern England, where he worked as a rent collector and clerk until he retired in 1952. Painting mostly at night in his free time (a recent film-biography shows him at a lonely man at the beck-and-call of his cantankerous bed-bound mother), he has sometimes been dismissed as a "Sunday painter" but he had studied intermittently at art schools, including the Manchester School of Art, over a period of some twenty years. Indeed, one of his most eminent teachers was the French painter Adolphe Valette who produced several memorable Manchester cityscapes of his own in the earlier part of the century.

Rather than Valette, however, Lowry has been likened to members of the Camden Town Group with whom he shared a Post-Impressionistic style that favored urban subjects. Lowry's most characteristic pictures feature firmly drawn backgrounds against which groups or crowds, painted in his signature "matchstick men" manner, go about their daily business. Many of his paintings record his immediate surroundings, but others draw, in part at least, on his imagination. One can locate an element of humor in his work but he is known mostly for what art historian John Rothenstein called "a kind of gloomy lyricism". His first one-man exhibition, at the Reid and Lefevre Gallery, London in 1939, established his name outside of Lancashire, and his reputation steadily increased thereafter, although his new-found fame did not alter his humble way of life. He turned down all honors in his lifetime, including a knighthood.

Lowry's popularity amongst the British public reached its peak in 1978 when a song, Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs (Lowry's Song) by the British music duo Brian and Michael reached No. 1 in the music charts where it stayed for three weeks. The song included the following lyric:

now canvas and brushes were wearing thin

when London started calling him

to come on down and wear the old flat cap

he said tell us all about your ways

and all about them Salford days

is it true you are just an ordinary chap

and he painted matchstalk men and matchstalk cats & dogs

he painted kids on the corner of the street

that were sparking clogs

now he takes his brush and he waits

outside them factory gates

to paint his matchstalk men and matchstalk cats & dogs

The most comprehensive collection of his work is housed at The Lowry, a large arts centre that opened in Salford in 2000. In addition to his signature works, the collection includes a number of unusual fetish drawings of women that only came to light after his death.

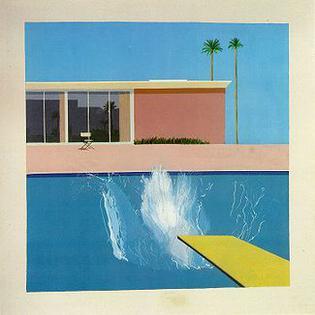

A Bigger Splash

Painted around the time of the summer of love, David Hockney's work represents the shedding of a restrictive and restrained British sensibility that tied in with the advancement of British Pop Art. In this painting, the viewer stands at the edge of a pool, into which an unknown person has just jumped (or dived) from a diving board. The water in which he has submerged was completely still; there is no ripple or texture to be seen. In contrast, his presence is marked only by an upward explosion of water, splashing skywards in sheets. Behind is a low building rendered in warm pinks, with a large window reflecting palms and buildings in gray. Beyond, the clear blue Californian sky is interrupted only by two, tall still palms. It is an unpeopled scene; the only other suggestion of human activity provided by an empty solitary chair.

Hockney, one of Britain's best-known artistic exports, has lived much of his life between the United States and Bradford, in West Yorkshire. In tribute to William Hogarth, his first trip to America saw him drawing his own version of A Rake's Progress as he chronicled his own explorations into the 1960s Queer scene. The idea of freedom and sunshine he found in Los Angeles is revealed in his series of water paintings, showing homoerotic images of men swimming, emerging from swimming pools and in the shower. As such his work was considered bold and outrageous (homosexuality was not decriminalized in the UK until 1967). But the mood of this particular work is hard to gauge. In the US, Hockney may have found freedom and pleasure, but as critic Jonathan Jones asks, "Is A Bigger Splash a happy painting or a sad one? The upward rush of white water [...] hangs ghostlike in the air, frozen by art. The diver has vanished underwater. Apart from the splash, the hot day is completely motionless. Palms, sky, the surface of the pool - an impersonal stillness prevails. Is this the beginning or the end of something?"

Acrylic on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Three Figures and Portrait

Born in Dublin in 1909 to English parents, Bacon emerged as a dominant figure in post war British art. He spent the majority of his life working in London where he developed his unmistakable style of figurative painting. Referred to by Margaret Thatcher as "that man who paints those dreadful pictures" (and inadvertently enhancing his already enviable reputation!), Bacon is a truly iconic British painter whose art transported the spectator into a world of human suffering, psychosis and even death. A time of great creativity and experimentation, the 1950s was an important decade for Bacon. Indeed, his international standing reached new heights when he exhibited with Ben Nicholson and Lucian Freud in the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1954. Bacon's work took on wider national significance however, when, in the mid-1970s, he joined an elite cadre of new figurative artists.

In 1976 R. B. Kitaj curated the Human Clay exhibition featuring 80 paintings and drawings by Lucian Freud, David Hockney, Peter Blake, Stephen Buckley, Richard Hamilton, Allen Jones, William Roberts and Euan Uglow. The exhibition is best known however for Kitaj's catalogue essay in which coined the term "School of London". The School of London would mount a forceful challenge to the avant-gardists preference for Minimalism and Conceptualism and it would soon focus on the output of just six painters: Bacon (who was not part of the Human Clay exhibition) Michael Andrews, Auerbach, Freud, Kitaj and Kossoff. Between them, the School of London expanded the possibilities for figurative art and brought it new critical respectability.

In addition to the disfigured heads and bodies, and his morbid fascination with animal carcases (witnessed here in the left sided figure's protruding spine), Bacon's style, which drew on a disparate range of influences including Van Gogh, Eadweard Muybridge, Velazquez and filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, was characterized by figures in motion set against still backgrounds. In this image, two twisted human figures occupy a claustrophobic room while in the foreground a bird-like form is contained (restrained?) within a geometric frame. The figures are being looked upon by a portrait of a man nailed to the wall. All three human figures are thought to be that of George Dyer, Bacon's lover who committed suicide in 1971. It is unclear what the disturbing bird-like creature in the foreground represents. There us some suggestion that it is a Fury, feared agents of divine judgement according to Greek mythology, or perhaps a Harpy, which Bacon had introduced as a symbol of mockery or malice. In either case, it brings a disquieting presence to an already punishing image.

Untitled (House)

Whiteread studied painting at Brighton Polytechnic before moving to the Slade School of Fine Art in London where she majored in sculpture. While at Slade she made the acquaintance of Tracey Emin and Gary Hume and thus begun her association with the YBAs. Having already won the Turner Prize for Untitled (House) in 1993 (and having been shortlisted for the same award in 1990), Whiteread exhibited with the YBAs at the notorious "Sensation" exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1997. Though she did not court publicity in the way some of her more media savvy colleagues had, on its unveiling on 25 October 1993, Untitled (House) had already caused a sensation in its own right.

Sitting between a busy traffic junction and the Regent's canal, Wennington Green is in Bow, East London, an area that for two decades had succumbed to various failed attempts at urban gentrification. The terraced houses around Wennington Green had been heavily bombed during the Second World War and they were among the properties marked for demolition in order to make way for a "green corridor" around the new financial district of Canary Wharf. Having gained the appropriate planning permissions, Whiteread and her team pumped the old house at 193 Grove Road with liquid concrete before then demolishing its exterior. Turning the house "inside-out" as it were, Whiteread had created an inversion of domesticity - a house "not for living" and an impression of something that no longer existed - that suggested a meditation on the relationship between human beings and the spaces they inhabit.

As soon as it was unveiled, Untitled (House), polarized opinion amongst the denizens of Bow, in the popular press, and amongst seasoned art critics. Of the latter, Andrew Graham-Dixon was celebrating "one of the most extraordinary and imaginative public sculptures created by an English artist this century" while Brian Sewell condemned the piece as "meritless gigantism". Despite, or perhaps because of, the controversy, Untitled (House) drew advocates and pilgrims from all over the world even though the sculpture stood for only 80 days before it was demolished by the local authority leaving not trace or commemoration of the work. Whiteread was asked later if she thought her most famous sculpture might have become something of an albatross. In reply she stated: "I was always aware of that, but no. I'm very proud of House [...] and I don't want to sound arrogant [...] but it opened up a dialogue. It really did change contemporary art in the UK".

Plaster and steel frame - now destroyed

The Pharmaceutical Paintings

In an article published in 2007, The New York Times called Hirst a "shining symbol of our times, a man who perhaps more than any other artist since Andy Warhol has used marketing to turn his fertile imagination into an extraordinary business". The most prominent and financially successful of all the YBAs, Hirst made his name pickling (and sometimes dissecting) dead animals in formaldehyde. But his bigger achievement has been to create (like Warhol) a recognizable "Hirst" brand. His "spot" series is now highly recognizable, only to be surpassed by his "Shark" - his iconic 1991 sculpture, titled The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, that is now considered a prime example of contemporary art.

Produced between 1986 and 2011, and reflecting the artist's preoccupation with the theme of mortality, the spot series was introduced with his "Pharmaceutical" paintings. In fact, Hirst would create a total of thirteen sub-series under the spots category, his overarching aesthetic goal was to find a way to use color in a way that moved beyond Expressionism: "to do those colours, and do nothing [...] It was just a way of pinning down the joy of colour" he said. In the "Factory" spirit of Warhol, Hirst employed assistants to create his spot paintings which could in theory yield a random and infinite range of color combinations. Hirst stipulated that all residues of human intervention, such as the compass point left at the centre of each spot, were to be concealed so as to give the false impression that the hand painted works had been mechanically produced.

In 1988 Hirst organized the so-called "Freeze" exhibition which is considered by many to have been the launching pad for what would become the YBA movement, and "a golden moment of British art" according to art critic Johnathan Jones. Hirst was able to secure the loan of a redundant warehouse in London's south-east dockland which he and his colleagues transformed into a makeshift exhibition space. Most of the 16 exhibiting artists were, like Hirst, ex-students of Goldsmiths College of Art including Mat Collishaw and Anya Gallaccio. For his part, Hirst painted his near identical spot paintings - called "Edge" and "Row" - directly onto the warehouse wall. However, Hirst's bigger achievement was in his ability to secure a sponsorship deal that allowed for the production of a professional exhibition catalogue that was widely distributed in galleries and bookshops ahead of the Freeze exhibition itself. Thanks in no small part to the catalogue, the exhibition caught the attention of several notable curators and Hirst was celebrated for his entrepreneurial savvy. Hirst's Goldsmith's tutor Craig Martin saw things slightly differently however: "It amuses me that so many people think what happened was calculated and cleverly manipulated whereas in fact it was a combination of youthful bravado, innocence, fortunate timing, good luck, and, of course, good work. It caught people's imagination".

Acrylic paint on canvas - Gagosian Gallery, New York

30 St Mary Axe (known colloquially as "The Gherkin")

This distinctive skyscraper stands proud at the heart of the City of London's business district and has become an iconic landmark on the capital's skyline. It was designed by Norman Foster, whose firm Foster and Partners also designed the Reichstag in Berlin, London City Hall, the Great Court and Reading Room at the British Museum, and the new Wembley Stadium. In contrast to the rectangular concrete high rises that neighbored the building at its inception, the Gherkin is rounded and covered in reflective glass; its curved structure enabling it to find a patch of blue sky to reflect on a grey day. As art critic Jonathan Jones noted: "Its entire body curves at every point. It glitters and reflects all over, creating optical patterns that change with distance, and with the times of day. It is a masterpiece that opens new possibilities for world architecture."

The building, which houses offices and restaurants, comprises an elongated, curved, shaft with a rounded end that has been described as "reminiscent of a stretched egg". Adjacent buildings added since its completion have complemented its original design, echoing its bright glass and curved edges. Jones added: "Where other recent architecture has a lot in common with the extravagance of the baroque, Foster and his team have created a form that is manifestly in the classical tradition [...] Its expansiveness culminates in a dome that rhymes with that of St Paul's. Far from being a stranger on the London skyline, this is a shape that Wren, or Michelangelo, or any of the architects of the European great tradition would have recognized, admired and envied."

The Gherkin has helped London compete on a national stage, not just in terms of business and industry, but architecturally. Reminiscent of Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao and comparable to New York's Chrysler Building, the Gherkin is in Jones's words "a masterpiece that opens new possibilities for world architecture."

Glass and steel - City of London

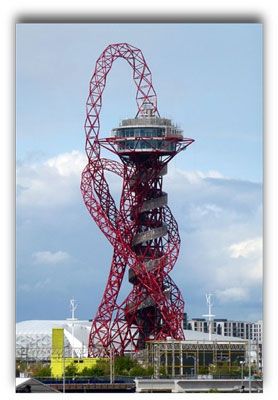

ArcelorMittal Orbit

The ArcelorMittal Orbit is the UK's tallest sculpture and was designed, in conjunction with engineer Cecil Balmond, as a new landmark to celebrate London's 2012 Olympics (an estimated 130,000 people visited the structure during the Games). The sculpture's name combines that of ArcelorMittal Steel company, its chief sponsor, with that of Orbit, the original working title for the design. Made from 600 pre-fabricated star-like nodes, the structure also contains a staircase, elevators, an interior viewing platform and, from 2016, the addition of an enormous helter-skelter slide designed by the German Conceptual Artist, Carsten Höller.

Made with the equivalent of 265 double-decker buses worth of steel, and held together with 35,000 rivets, installation artist Anish Kapoor wanted the work to be both a visual and experiential event, encouraging visitors to ask themselves questions about how they occupy and move through space. Beginning in darkness beneath a huge domed steel canopy, the visitor travels up via the lifts towards the light at the top of the structure where they are met by two huge concave mirrors - Kapoor's trademark - bringing the sky in as if in the lens room of a telescope. The visitor is then returned to earth (in just 40 seconds) via Höller’s helter-skelter that twists its way through the spectacular steel sculpture.

Kapoor's work is highly international and he has set up momentous public sculptures around the globe. This work, with its spirals and steel bears similarities to Vladimir Tatlin's Tower (project for the Monument to the Third International (c. 1917)). But while Tatlin's work was a monument to nation, Kapoor's is more personal. The artist was fascinated with origins, and with this work the "viewer" starts from the bottom, ascends to the top, only to slide down to their roots, replicating one's journey through life. Kapoor said the work acted as a meeting point between sculpture and architecture: "I wanted the sensation of instability, something that was continually in movement. Traditionally a tower is pyramidal in structure, but we have done quite the opposite, we have a flowing, coiling form that changes as you walk around it [...] It is an object that cannot be perceived as having a singular image, from any one perspective. You need to journey round the object, and through it. Like a Tower of Babel, it requires real participation from the public." This comparison is significant; East London in 2012 was a melting pot of nationality, culture and language and the Games and the ArcelorMittal Orbit had a vital role to play in promoting a multinational British identity.

Steel structure - Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, Stratford, London

Early British Art

Beginnings

Some of the earliest examples of British art come from sumptuous metalwork of the Anglo-Saxon period and the stone churches, abbeys and castles belonging to the early medieval period. Very rare, early decorative works, including the famous Lindisfarne Gospels (c. 690-750 AD) with their intricately patterned lacework, were also to be found in churches throughout Saxon England. While little remains of their original interiors, buildings such as Exeter Cathedral (the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter) still stand today as an examples of early Gothic architecture. The cathedral's Norman Towers were completed by 1133, while the west front image screen is considered one of the great architectural features of Medieval England. The cathedral also houses the longest uninterrupted vaulted ceiling in England as well as an early set of misericords and an astronomical clock.

According to art historian E. H. Gombrich it was not until the thirteenth century that artists (or rather artisans as they would have been then regarded) began to create pictures "copied and rearranged from old books," of the apostles and the Holy Virgin. Yet much of the decorative and religious art produced during the middle ages (c. 410-1485 AD) was destroyed during the century of iconoclasm that begun in 1536 when King Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries under the English Reformation. In setting up the Protestant Church (and thereby breaking away from the rule of Roman Catholicism) the monarch sanctioned the destruction of art housed in churches and cathedrals and many thousands of sculptures, paintings, carvings and stained glass windows were smashed and burned.

The English Renaissance

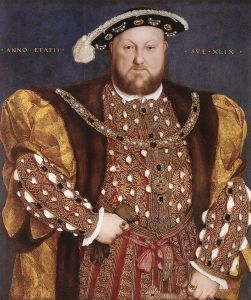

The period of the English Renaissance (c. 1520 to 1620) differed from the earlier Italian Renaissance in that playwrights and poets were awarded higher societal status than visual artists. In the visual arts, however, religious painting, which was widely demonized as a relic of the Catholic church, was overtaken by portraiture which took on a dominant role in promoting the Tudor dynasty (1485-1603). But it was in fact a German painter working in England who became one of the greatest artists of the English Renaissance. Hans Holbein the Younger, court painter to Henry VIII, was the artist who did most to bring the Tudor age to life which he did by idealizing the king; lengthening his squat legs and transforming his conspicuous folds of fat into muscle.

Elizabethan Portraiture and Beyond

The transition to Elizabethan rule (daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth I was crowned in 1558) brought with it a period of great social upheaval though this was not reflected through its portraiture. Indeed, while portrait painting grew in popularity, artists who had previously found themselves employed by the church, brought with them the tranquil hieratic quality of religious painting. There are numerous portraits of the British ruling classes dating from this period though relatively little is known about the men (or women) who painted them. A small number of portraits have been attributed to George Gower, the first Englishman to be appointed Serjeant Painter of the Queen in 1581. Though infused with all the courtly and refined qualities of the best portraits, Gower's work, often singled out as representative of British portraiture as a whole, still lacked the penetrating depth of space that had come to distinguish the work of painters from the continent at the time.

Elizabethan architecture had tended to reflect a time when post-Reformation Britain sought glory and legacy. Stately homes, known as "prodigy houses," were built for the English ruling classes with decorative estates such as Burghley House, Hardwick Hall, Longleat and Wollaton Hall conceived of as architectural works of art. Personally responsible for introducing the architecture of the Roman Renaissance to Britain, Inigo Jones designed England's first neo-classical building: the Royal Palace at Banqueting House, in London's Whitehall (completed in 1622).

English Art Before and After the Civil War

Despite the success of artists such as Gower, William Dobson, Peter Lely, Nicholas Hilliard, Isaac Oliver and Robert Walker, Europeans were held in higher esteem than British artists and the Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck arrived from Antwerp in 1632 to be employed by the court of Charles I. Influenced by the Baroque period and the High Renaissance, van Dyck's work, according to art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon, brought a new "openness and freedom, a new opulence, a new brightness of color, a new sensuality and a new sense of drama to British painting." Indeed, Charles I was captivated by Renaissance and Baroque art, and he became a collector, buying works by Raphael and Titian and bringing them back to England. To showcase Stuart power, meanwhile, Charles I employed van Dyck's erstwhile tutor and mentor Peter Paul Rubens to create a vast painted ceiling within the Royal Palace (the three main canvases, depicting the peaceful reign of Charles, were installed in 1636). Historians have surmised that Rubens's ceiling would have been the last thing the King would have seen before his beheading at the Royal Palace in 1649.

The period between 1650-1730 saw considerable social and political upheaval. The monarchy was restored in England in 1660 as Charles II returned to the throne following the English civil war and the period of Oliver Cromwell's Commonwealth (1642-59). There was the plague, the Great Fire of London and the creation of the United Kingdom in 1707. Landscape painting, still lifes and "the conversation piece" became recognized genres of painting and the period saw the first female professional painter, Mary Beale. The era also saw a classical revival as architects looked to northern Europe for inspiration in buildings such as Hardwick Hall, Wollaton Hall, Hatfield House, and Burghley House.

British Art 1600-1900

The Seventeenth Century and Enlightenment

The second half of the seventeenth century saw advancements in science and (led to a large extent by Christopher Wren) artists and thinkers started to look to the natural world as the source of all knowledge. Wren himself produced drawings of magnified creatures, including a flea and a louse, while Peter Lely shocked the public with his sensual nudes. Following the Great Fire, Wren became the prime architect of London, and he started rebuilding St Paul's Cathedral with a cupola (placed atop the second largest dome in the world after that of St. Peters in Rome) a structure that had never before been seen in Britain before the cathedral was constructed (1675-11). Meanwhile, aristocratic houses of the eighteenth century tended to evoke ancient Greek and Roman architecture, as seen in Buckinghamshire's Blenheim Palace, inspired by Alexander Pope's writing and designed in part by Capability Brown.

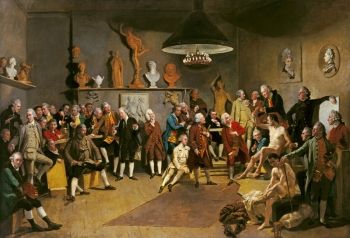

Coinciding with the dawning of the age of "scientific reason" - better known perhaps as the age of "Enlightenment" - 1690s London became the biggest metropolis in the Western world, and travelers from all over the country came to live in the city whose changing fortunes were documented by portraitist and satirist William Hogarth. Hogarth has been credited with being the first to create a British School of Art. His "modern moral subjects" were groundbreaking, not just in their frank subject matter, but in the role of the artist himself. Indeed, Hogarth was the first artist to support himself financially (independently of wealthy patronage) and his role set a precedent for many of the artists that succeeded him. The philosophy of Enlightenment could also be seen in George Stubbs' anatomically exact paintings of horses.

Away from the capital meanwhile, the themes of the Enlightenment were explored explicitly by Joseph Wright of Derby who aligned his art, albeit rather theatrically, with the scientists, industrialists and inventors of the Industrial Revolution. Wright became known in fact for his industrial scenes and for his use of lighting for dramatic affect. (It was rumored that Wright had aspired to become a portrait artist but was deterred having seen Thomas Gainsborough's work.)

The Royal Academy

The idea of an Academy dates back to the fourth century BC when Plato established a school to teach philosophy. Raphael followed suit in 1509 with the School of Athens. Based on the teachings of ancient Greek philosophy, Raphael painted four stanzas representing different fields of knowledge but with a self-portrait on the right of the picture, as an assertion of Renaissance artists' claim to be deserving of a new and higher education. The most influential European academy was arguably the Académie Royale de Peintre et de Sculpture which was founded in Paris in 1648.

Soon after its establishment, the important connection between centralized academies and the state was presumed and their popularity spread throughout Europe during the 18th century. Academies were vital in fostering national schools of painting and sculpture and remained pinnacles of aspiration for most artists. In addition to practical skills, artists learned academic subjects such as history, since history painting - which borrowed subjects from literature, mythology and the Bible - was widely regarded as the most demanding genre, although academies also produced skilled portraitists and still life painters. A further, and most important, function of the academy was to provide artists with a regular exhibition venue. Since the authority of the academies lent considerable authority to these juried shows, they often became the most important event in the exhibition calendar. This in turn lent further weight to the academies as arbiters of popular taste.

In 1768 a group of 36 artists and architects - including four Italians, a Frenchman, a Swiss and two women - signed a petition which was presented to King George III seeking his permission to "establish a society for promoting the Arts of Design." Having received his approval, the Royal Academy of Arts - or the RA as it was to become known - emerged as an independent institution ran by artists with an elected President. It became, in effect, the first British school of art. The RA provided an exhibition space, public lectures, an Art School and a School of Design. The aim of the RA was to elevate artists to the stature enjoyed by poets, dramatists and philosophers. Housed initially in Pall Mall in central London, its founder and first president was Joshua Reynolds, the leading English portraitist of the 18th century and Royal Academicians have included Angelica Kauffman, Mary Moser, Thomas Gainsborough, and John Everett Millais.

Like other academies, the RA placed history painting as the highest of the genres and required that the RA member show all his (or her) talents; not only the skill of eye and hand co-ordination, but also his (or her) mastery of the often complex and philosophical subject matter. The style considered appropriate for history painting was classical and idealized; what was commonly referred to as the Grand Manner was considered the epitome of High Art. The RA's second president was the American ex-patriot Benjamin West, and the King's personal "History Painter." An accomplished painter in his own right, he also possessed an "eye for talent" and is said to have consoled a young John Constable after one of his landscapes had been rejected by the Academy: "Don't be disheartened young man," he said, "we shall hear more of you again [for] you must have loved nature before you could have painted this."

Romanticism

With the dawning of Romanticism, many artists began to question the centralized authority of the Academy. Indeed, by the late-18th century, many artists were rejecting authority entirely. Modernists formed an opposition to "academic" art which was dismissed by them as old-fashioned and moribund. In this respect, one could argue that Romanticism carried the earliest seeds of 19th and 20th century Modern Art.

The Welshman Richard Wilson is considered a pioneer amongst Romantic landscapists. A close acquaintance of the French painter Joseph Vernet, Wilson was influenced by the landscapes of Claude Lorrain and Gaspard Dughet and he interpreted the English and Welsh (and Italian) landscapes in a style that in fact earned him the nickname "The English Claude" (sic). Wilson exhibited at the Society of Artists from 1760 and was in fact a founder member of the Royal Academy (though he sadly died in poverty in 1782).

In a reaction against the dispassionate objectivity of science, and the restrictive rules of the RA, Romanticism flourished. By the end of the 18th century artists began to turn inward - calling on the senses and emotions - for their inspiration. William Blake was one of the leading Romantic "insurgents" and his highly impassioned explorations in art and poetry paved the way for a new generation of artists amongst whom were John Constable and J.M.W. Turner, arguably the two greatest painters in British history. Turner took classical scenes and infused them with a new dynamic in painting in a way that had a profound influence on Claude Monet, the father of Impressionism, while Constable's ability to capture nature in vibrant color and fluid brush strokes had a deep impact on Eugène Delacroix and future generations of European and American landscapists, namely the French Barbizon School and the American Hudson River School.

The rise in British Romanticism was to coincide with the new Regency Period in British sovereign history. Though there is some disagreement on when it started and finished - the introduction to the Regency galleries in the National Portrait Gallery however describes "a distinctive period in Britain's social and cultural life [spanning] the four decades from the start of the French Revolution in 1789 to the passing of Britain's great Reform Act in 1832" - the Regency "spirit" was personified by the figure of George, Prince of Wales. In 1811 Prince George (the future King George IV) began his nine-year tenure as Prince Regent, replacing his father who was stricken with mental illness and deemed unfit to reign. The Prince - referred to by some as "the first gentleman of England" but ridiculed by others - brought with him a flamboyant feel for decadence and self-abandon. This image did not sit well with large portions of the public and political classes who thought Prince George had defiled the role of the monarchy, and duly treated him as a figure of derision. However, his vigorous spirit and general joie de vie was reflected in fine art, in literature, in architecture and in fashion.

The Romantic spirit was well-established by the time of the Regency and it continued to infuse the visual arts in the paintings but also in literature with poets of the stature of Wordsworth, Byron, Coleridge and Shelley and novelists Walter Scott and Jane Austen. In the field of architecture, meanwhile, John Nash, known for his highly picturesque style and his ability to combine past and present styles, became a personal friend of the Prince Regent who accordingly appointed him architect to the Surveyor General of Woods, Forests, Parks and Chases. In addition to re-modelling Buckingham Palace, The Royal Pavilion at Brighton and the Royal Mews, Nash was commissioned to develop large areas of central London and is associated with the Gothic Revival, an architectural style that drew its inspiration from medieval architecture. The Gothic Revival, associated also with the likes of James Wyatt (Fonthill Abbey), and Charles Barry and A. W. N. Pugin (Palace of Westminster), favored picturesque and romantic qualities over practical structural and functional factors.

Formed in 1824, and lasting roughly a decade, Samuel Palmer was, with Edward Calvert and George Richmond, a founder member of The Ancients. Thought by some to be the first British manifestation of an artistic "brotherhood;" they pre-dated, though lacked the impact of, the Pre-Raphelites. The Ancients were deeply influenced by William Blake with whom Palmer became personally acquainted (albeit that the men were separated in age by two generations). Like Blake, the group railed against "stuffy" academic painting, but also the incessant march of industrialization. Unlike, say, Hogarth, or the novelist Charles Dickens, however, The Ancients looked back towards a "better" (ancient) age through its faith in gnosis and its mythical pastoral visions.

It is worthy of note that in the march of a progressive British art, individuals like Alfred Stevens, a sculptor, draughtsman and designer who only "knew but one art" and who was roundly dismissed as being a mere imitator of the past, remained steadfast in his reverence for Classical Art. While acknowledging his preoccupation with the masters of the past, in his history of the Tate Gallery, Rothenstein reserved this glowing praise for Stevens: "Looking at King Alfred and his Mother (1848), so bold in the sweep of its composition, so masterly in drawing, so masterly, too, in the variety and richness of effect obtained from the manipulation of a narrow range of tones and a few subdued colors, and so elevated in feeling, it is difficult to believe that this was not the work of a master wholly dedicated to painting". One can add the name of George Frederic Watts, an artist known for his monumental religious and ethical works, to the field of important English decorative painter who failed to find critical favor. Both men have, however, come under the scrutiny of historical revisionists who acknowledge their significant contributions to the canon of nineteenth century British art.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Arts and Crafts Movement

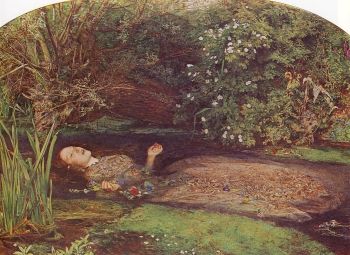

Founded in 1848, by John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood offered a more forceful challenge than the Ancients to the "official" art in British history. Opposed to the dominance of the British Royal Academy and its narrow preference for Victorian subjects and styles, which owed a debt to the early Italian Renaissance and Classical Art, the Pre-Raphaelites looked back to an earlier (before Raphael) period. The group believed painters before the Renaissance provided a better template for depicting nature and the human body realistically and that medieval craftspeople/artists offered an alternative vision to the austere and idealistic mid-19th-century academic approaches.

Above all, Pre-Raphaelitism championed the detailed study of nature and a true fidelity to its appearance, even if this risked showing ugliness. The Brotherhood also promoted a preference for natural forms as the basis for patterns and decoration that offered an antidote to the industrial designs of the machine age. As part of their reaction to the negative impact of industrialization, Pre-Raphaelites turned to the medieval period as an ideal for the synthesis of art and life in the applied arts. Their revival of medieval styles, stories, and methods of production had a profound influence on the development of the Arts and Crafts Movement which revived handicrafts in design. Their ethos was driven by the writer and critic John Ruskin and the textile designer, poet and novelist William Morris who designed elaborate decorative wallpapers that proved especially popular with the educated middle-classes. Ruskin and Morris deplored mass-production and were joined by noted craftsmen C. R. Ashbee, Walter Crane, and A. H. Mackmurdo, whose collective works proved precursors to Art Nouveau and Art Deco movements.

Women Artists Emerge

Emily Mary Osborn was the most important artist associated with the campaign for women's rights in the arts and arts education during the Victorian era. She trained as an artist at Dickinson's academy in Maddox Street and became an established figurative genre painter of "unpretending characters" during the 1850s. She was associated with Barbara Bodichon's Langham Place circle and the Society of Female Artists both of which campaigned vigorously for women's rights. In 1859 Osborn was one of the signatories of the women's petition to the Royal Academy of Arts to open its doors to female students and to the Declaration in Favour of Woman's Suffrage in 1889. As Alison Smith of Tate Britain recorded, Osborn enjoyed the support of important female patrons including Queen Victoria.

Known for her pioneering photographic portraits, Julia Margaret Cameron's images were considered (by non-conformists at least) to be highly innovative. Her portraits were often intentionally out-of-focus; surfaces often left scarred with scratches and other blemishes - a style now classified as Pictorialism. She was simultaneously criticised and revered for her unconventional compositions and her insistence that photography, still in its infancy in the mid-to-late 19th century, was already a legitimate art form. The daughter of Indian and French aristocracy, Julia Margaret Pattle married Charles Hay Cameron, a reformer of Indian law and education, in 1838. She became a prominent colonial hostess before the family relocated to southern England a decade later. Cameron, by now aged 48, took up photography as a career and within two years she had sold and gifted her photographs to the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria & Albert Museum), which, from 1868, granted her the use of two rooms as a portrait studio, effectively making her the museum's first ever artist-in-residence.

The British Museum

Offering free admission to all "studious and curious persons," The British Museum, housed in a seventeenth mansion called Montagu House at Bloomsbury, was the first public museum in the world. Opened in 1759, the museum's origins owe a debt to the physician and naturalist Sir Hans Sloane. Having collected some 70,000 artefacts in his lifetime, on his death he bequeathed his collection to King George II and the state with the proviso that £20,000 would be paid to his surviving family. Parliament accepted his proposal and the British Museum was duly established. The original collection consisted of books, manuscripts, specimens from the natural world and an assortment of coins, medals, prints and drawings.

Moving into the mid-nineteenth century, the museum expanded with Sir Robert Smirke's new quadrangular building and the round reading room housing high profile acquisitions including the Rosetta Stone, the Parthenon Sculptures, and the King's Library. To make room for its expanding collection, the museum's natural history collection was moved to a new site in South Kensington (what was to become the Natural History Museum). A key figure during the mid-century expansion was Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks who expanded the collection further to include medieval antiquities, prehistoric, ethnographic and archaeological artefacts.

In Smirke's original design, the museum's courtyard was envisioned as a garden it became the museum's Reading Room and its library department. In 1997 the library department was relocated to the new British Library in St. Pancras and an architectural competition was launched to re-design the courtyard as an open public space. The competition was won by Britain's greatest living architect, Norman Foster. The design of the Great Court was loosely based on Foster's own concept for the roof of the Reichstag in Berlin whereby every step in the Great Court revealed a new view on the visitors' surroundings.

The National Galleries

Complementing the British Museum, the nineteenth century saw the establishment of three of Britain's most important national art institutions, The National Gallery, The National Portrait Gallery and The National Gallery of British Art, all of which were based in London.

In April 1824 the House of Commons agreed to buy John Julius Angerstein's picture collection at a cost to the State of £57,000. This acquisition, which comprised of just 38 pictures, was to form the core of a new national collection that would be put on public display for the purposes of "enjoyment and education of all." The collection remained in Angerstein's house (in Pall Mall) but this setting was manifestly inadequate when compared to other national art galleries - notably the Louvre in Paris - and was derided in the press. In 1831 Parliament agreed to the construction of a purpose-built gallery with Trafalgar Square eventually chosen for its prime location.

Meanwhile, the idea of a dedicated British Historical Portrait Gallery (as it was first named) was introduced to the House of Commons in 1846 by Fourth Earl Phillip Henry Stanhope. It would be another decade before the House came around to the idea, however, with Stanhope first gaining the support of the House of Lords and Queen Victoria. The National Portrait Gallery was formally established in December of the same year with the so-called "Chandos portrait" (named after its previous owner) of Shakespeare being the first portrait to grace the Gallery. Lastly, with the National Gallery now firmly established, there was a growing feeling amongst the art establishment that the it deserved a "sister" gallery dedicated to British art. Run (until 1955) under the directorship of the National Gallery, the National Gallery of British Art (renamed Tate Gallery in 1932), designed by Sidney R. J. Smith, and built on the site of a former prison on Millbank on the banks of the River Thames, opened to the public in 1897.

British Impressionism

Though both Americans, John Singer Sargent and James Whistler can be credited with inspiring a British Impressionist movement. Whistler, who arrived in London 1863, tutored the artists Walter Richard Sickert and Wilson Steer and between them they founded the New English Art Club (NEAC) in 1886. Three years later, Sickert (who would become a founder member of the post-impressionist Camden Town Group) and Wilson organized an exhibition of London Impressionists with other members of the NEAC. In 1885, meanwhile, Singer Sargent arrived from Paris where he had met the great Claude Monet. Over the next few years, Singer Sargent made a major contribution to Impressionism in Britain with paintings such as Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (1885-6), arguably his most famous painting.

Pre-war British Art

Fin de Siècle, Art Nouveau and Art Deco

Fin de Siècle, a French term used to describe Symbolism, Decadent movement and related styles, most notably Art Nouveau, reached its peak of popularity in the 1890s. The term expressed a sense of apocalyptic dread as the century drew to a close (though at that time commenters had not predicted WW1). Minded artists expressed a sense of the end of a phase of civilization, and Oscar Wilde's writing led the charge for a new fashionable sense of pessimism. Aubrey Beardsley's artistic career was short but ground-breaking and his easily-reproduced block print work led the Art Nouveau movement. The architecture and design of Charles Rennie Mackintosh meanwhile brought Art Nouveau into people's homes and he has become known as a father of British Modernist architecture. Art Nouveau would later give rise to Art Deco which was incorporated into the design of the iconic London Underground system.

The Bloomsbury Group

The Bloomsbury Group was a group (rather than a movement) of English writers, philosophers and artists who would meet in the Bloomsbury district of London, close to the site of the British Museum. Writers and artists would meet for drinks and conversation at the home of artist Vanessa Bell and her writer sister Virginia Stephen (the famous Virginia Woolf). The core group, which formed in 1905, was made up of artists Duncan Grant, John Nash, Henry Lamb, Edward Wadsworth, art critic Roger Fry, literary critic Lowes Dickinson and philosophers Henry Sidgwick, J.M.E. McTaggart, A.N. Whitehead and G.E. Moore, and the economist John Maynard Keynes. Group discussions tended to focus on issues of aesthetics and philosophical questions and were deeply influenced by Moore's treatise on twentieth-century ethics, Principia Ethica (1903) and by Whitehead's and Bertrand Russell's three-volume tome on symbolic logic, Principia Mathematica (1910-13). The Bloomsbury Group would survive for a further thirty years and future attendees would include such luminaries as Bertrand Russell, Aldous Huxley and T.S. Eliot.

The Camden Town Group

Formed out of the anti-establishment Allied Artists Association, The Camden Town Group was named after the cosmopolitan and vibrant area of north London where its members resided. Notwithstanding the fact that they produced some notable Post-Impressionist landscapes (such as Spencer Gore's The Cinder Path (1912)), the Group, made up of artists including Gore, Harold Gilman and Walter Sickert, aimed to reflect the realities of modern urban life and would meet regularly at Sickert's Camden studio. Following an exhibition of English and French Post-Impressionism at the Royal Albert Hall in 1911, the Camden fraternity sponsored three successful exhibitions at the Carfax Gallery between 1911-12 (they disbanded in 1914).

The Group's own works explored issues including social class, sexuality, modernity and the urban environment while the exhibition also introduced early Fauve and Cubist paintings to the British public. As art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon noted, the Group "for all its drabness, does get to the heart of a distinctively British twentieth century aesthetic. The mood of the unswept street, the spirit of the abandoned car park at night, the milieu of the overflowing urinal or the uncomfortable, unmodernized football stadium through which a cold wind blows - the British have taken a grim, stoical, self-flagellatory pride in such things." Though there was no direct association between them, one of Britain's most popular 20th century painters, L. S. Lowry, produced his famous "matchstick" Northern industrial landscapes with the same post-impressionistic spirit as the Camden Group.

Vorticism

The Vorticists - named by the English painter, satirist, critic and philosopher Wyndham Lewis, and the American poet Ezra Pound - became Britain's first radical avant-gardist group. Wyndham Lewis, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, David Bomberg and Jacob Epstein celebrated the energy and dynamism of the modern machine age and in so doing declared an assault on staid British traditions. Given their reverence for the "machine age" the Vorticists were often likened to the Italian Futurists. But the life of the movement was cut short with the onset of World War I.

The movement is perhaps best remembered, however, for its journal-cum-manifesto BLAST, edited by Wyndham Lewis. With its bright pink cover, and the title BLAST written in bold, black letters against a bright pink background, the first section of the journal presented a sequence of twenty-plus pages in the form of a manifesto. Each page featured a dramatic piece of graphic design, in which the contributors would "Blast" (hate) or "Bless" (love) different things; often at once: "Blast France, Blast England, Blast Humour, Blast the years 1837 to 1900" and then "Bless England, Bless England for its ships which switchback on blue, green and red seas." BLAST also published Lewis's play, Enemy and the Stars, which was largely unintelligible and positively unperformable.

British Surrealism

The emergence of fascism across Europe during the 1930s turned the contemporary art world on its head. As Tate curator Chris Stephens noted, debates arose "not only between the avant-garde and the academy, but also between modern artists, about the appropriate response to the rise of fascism. Abstract artists, Surrealists and Social Realists all interpreted that political imperative in different ways." British Surrealism emerged within this period of uncertainty, limited mostly to two groups; one in London; the other in Birmingham. The English poet David Gascoyne had been drawn to Paris in the early 1930s having been inspired by the French Surrealists, and following a chance meeting with English artist and historian Roland Penrose and poet Paul Éluard, he set out to create tangible links between British and French Surrealists. In fact, Gascoyne wrote the "First English Surrealist Manifesto" in 1935 in Paris (and in French), and it was first published in the French review Cahiers d'art.

The International Surrealist Exhibition took place in the June 1936 at the New Burlington Galleries in London. It was attended by speakers including Éluard, André Breton, Salvador Dalí, and English poet and critic Herbert Read. Members of the Birmingham group - including Conroy Maddox, John Melville, Emmy Bridgwater, Oscar Mellor, and Desmond Morris (better known as an anthropologist) - refused to exhibit, however, claiming that the London group - including the likes of Paul Nash, Eileen Agar, Ithell Colquhoun, E. L. T. Esens, Herbert Read, John Tunnard - lived "anti-Surrealist lifestyles." Some of the Birmingham group did attend, however, hoping to make the acquaintance of their hero, Breton. Though not a formal member, sculptor Henry Moore became an associate of the British Surrealist group, showing seven pieces at the International Surrealist exhibition of 1936. It is an interesting detail too, that, though never formally affiliated with the group, the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas also attended, performing in his own "Surrealist happening" which involved offering attendees cups of boiled string! The London group dissolved in 1951 though the Birmingham group continued into the 1950s on a rather informal basis.

The Euston Road School

Founded by William Coldstream, Victor Pasmore and Claude Rogers in 1937, and existing as a group for roughly two years (when its members joined the war effort), the so-called Euston Road School are worthy of mention in the context of early-to-mid-twentieth century British modernism. The School was opposed to the rise of avant-gardism; their goal, born of a clear leftist political position that promoted naturalism and socially relevant art, being to treat traditional subject matter (such as portraiture, nudes, landscapes) in a realist style while stopping some way short of the dogma of Social Realism.

St Ives School

Cornwall, in the South West of England, was (or is) renowned for the unique quality of its natural light. As such it has been a place of pilgrimage for many painters; especially so since the Great Western railway line opened in 1877, putting the county within easy reach. In 1928 Ben Nicholson and Christopher "Kit" Wood visited St Ives where they made the acquaintance of Alfred Wallis. Wallis's painting was to have a profound impact on the future direction of Nicholson's work and later, in 1939, he and his wife, the sculptor Barbara Hepworth, relocated to St Ives where they were joined by the Russian Constructivist sculptor Naum Gabo.

After the war, and with Hepworth and Nicholson as its avant-gardist mascots (Gabo had moved on by 1946), St Ives became the centre for modern and abstract developments in British art and many younger abstract artists were drawn to the area giving rise to the name St Ives School, though in point of fact they were never a formal group in the strict sense. However, the "group" were generally inspired by the West Cornwall landscape, using its shapes, forms and colors to inform their work. The St Ives School had run its course by the 1960s but in 1976 the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculptural Gardens opened in her previous studio, while in 1993, Tate St Ives (which had already taken over the running of the Hepworth museum in 1980) helped preserve and promote the county's proud modern heritage.

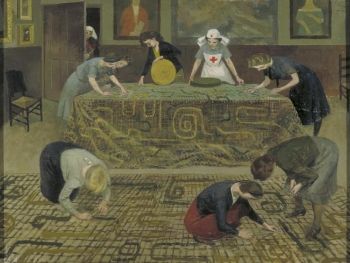

War Art

Chaired by Kenneth Clark, Director of the National Gallery under the administration of the Government Ministry of Information, the British War Advisory Scheme was set up in 1939. At their monthly meetings, the committee would select artists whose primary goal was to create imagery for propaganda purposes but on the proviso that their work would do more than merely illustrate posters and pamphlets. By the end of the war the official war collection was comprised of more than 5000 works. War art was produced by the likes of brothers John and Paul Nash who depicted soul-less images of trench warfare, war-torn landscapes and the horror of conflict, Henry Tonks, mean-while, produced harrowing portraits of injured soldiers. On the home front, Evelyn Dunbar was the only woman to be salaried as an official war artist and she produced paintings and sketches of the manual work undertaken by the Women's Land Army who, amongst other duties, took on agricultural roles vacated by conscripted soldiers.

Post-war British Art

Cecil Beaton, Norman Parkinson and Vogue

In March 1951, Vogue carried a three-page spread entitled American Fashion: The New Soft Look. Cecil Beaton had taken the photographs for designers Irene and Henri Bendel using Jackson Pollock's Action Paintings as a decorative backdrop for the Bendels' haute couture. The images represent a tension between the muscular and intense character of Pollock's art, and the soft, feminine nature of the fashion models. The élan for which Beaton had become well known asked one to question in fact the qualitative difference between the high art and commercial fashion.

Like Beaton, Norman Parkinson worked through several decades in the fashion industry. Before he joined British Vogue in the early 1940s - an association that would last nearly four decades - the magazine, then in the infancy of color photography, had relied on photographs borrowed from its American sister publication. Out of sheer necessity, this situation would continue during the war years but Parkinson's English pastoralism gave British Vogue a very distinctive identity and his first Vogue photographs were taken in the English countryside in 1941. As his career developed, many of Parkinson's shoots were set abroad, often in Africa or the Caribbean. This lent his work an exotic, jet-set appeal that proved very popular in Britain during the austere years of the 1950s.

British Pop Art