Summary of Richard Hamilton

Richard Hamilton was the founder of Pop art and a visionary who outlined its aims and ideals. A lollipop from one of his early collages furnished the movement with its title. His visual juxtapositions from the 1950s were the first to capture the frenetic energy of television, and remind us of how strange the vacuum, tape recorder, and radio must have seemed for the first generations that experienced them. "Pop art" the British artist declared, would be: "Popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and Big Business." While less of a household name than Andy Warhol, it was Hamilton who laid the groundwork for Pop art, and first defined its aims and ideals.

Accomplishments

- Hamilton introduced the idea of the artist as an active consumer and contributor to mass culture. Up until then (especially in Abstract Expressionist circles) the prevailing view was that art should be separate from commerce. Hamilton gave other artists permission to consider all visual sources, especially those generated by the commercial sector. There is no more influential idea in art to this day.

- For Hamilton, Pop art was not just a movement, but a way of life. It meant total immersion in popular culture: movies, television, magazines and music. As his alignment with the Rolling Stones and the Beatles (for whom he designed The White Album cover as a limited-edition print) demonstrates, he succeeded in bridging this gap between high art and consumer culture, paving the way for Andy Warhol, Studio 54, and the Velvet Underground.

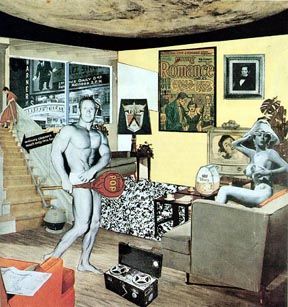

- With uncanny accuracy, his work seems to predict that of nearly every other major Pop artist. Details in "Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing?" in particular, read like a crystal ball containing Warhol, Lichtenstein, Wesselmann, and Oldenburg, before these artists' careers had developed. Of course, the reality was that all these artists were looking closely at his work, and used it to come up with their own ideas.

- Hamilton reminds us that Pop art originated in England. He was among a group of young British artists, architects and critics who got together in the 1950s to discuss aspects of visual culture that weren't considered part of a traditional artist's training - cowboy movies, science fiction, billboards, and household appliances. Most of these were imports from America, which made them especially fascinating. Before coming up with Pop, the term they used for the movement was "the new brutalism" - more descriptive of the deliberate assault on general art themes and depictions that one finds in Hamilton's imagery.

Important Art by Richard Hamilton

Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing?

This collage was created by Hamilton for the catalog of the seminal 1956 exhibition at London's Whitechapel Gallery, "This is Tomorrow." The exhibition is now generally recognized as the genesis of Pop art, and as early as 1965 this particular work was described as "the first genuine work of Pop." Within it are a contemporary Adam and Eve, surrounded by the temptations of the post-War consumer boom. Adam is a muscleman covering his groin with a racket-sized lollipop. Eve perches on the couch wearing a lampshade and pasties.

Hamilton used images cut from American magazines. In England, where much of the middle class was still struggling in a slower post-war economy, this crowded space with its state-of-the-art luxuries was a parody of American materialism. In drawing up a list of the image's components, Hamilton pointed to his inclusion of "comics (picture information), words (textual information) [and] tape recording (aural information)." Hamilton is clearly aware of the work of Dada photomontage art, but he's not making an anti-war statement. The tone of his work is lighter. He is poking fun at the materialist fantasies fueled by modern advertisement. This whole collage anticipates bodies of work by future pop artists. The painting on the back wall is essentially a Lichtenstein. The enlarged lollipop is an Oldenburg. The female nude is a Wesselman. The canned ham is a Warhol.

Collage - Kunsthalle Tübingen, Tübingen

Fun House

Fun House, a collaborative work, was one of the greatest critical successes of the 1956 Whitechapel exhibition, "This is Tomorrow." It is also one of the earliest examples of Pop installation art. The architect John Voelcker created a structure which Hamilton then covered with oversized images from advertising and other popular culture sources. The huge sci-fi robot, with its flashing eyes and grinning switchboard mouth, was taken from a film set. Superimposed on it is the iconic shot of Hollywood film star Marilyn Monroe in a billowing white dress. A large three-dimensional model of a Guinness bottle accompanies these 2-dimensional images. Pop music played loudly from speakers, and a recording of a robotic voice, accompanied the installation, producing an environment of sensory overload, unlike what most of the gallery-going public in England had seen.

Like Hamilton's Just what is it that makes today's homes..., also included in the exhibition, Fun House is an absurd, hedonistic hodgepodge of pop culture sources. Here, however, in place of a domestic cornucopia, an anarchic and potentially sinister mood prevails. Whatever the robot's intentions are for the unconscious woman, they cannot be good. The only quotation from "high art" is a blaring image of sunflowers by Van Gogh, the notoriously mentally unstable genius known for cutting off his own ear.

Multi-media installation

Hommage à Chrysler Corp.

Though Hamilton was a multi-media artist, the elegant lines of this composition remind us that his way into art was through drawing. His command as a draughtsman underlies the complexity of much of his work, including this one, which at first glance appears to be totally abstract. On closer inspection (yet very hard to see), one can make out the form of a woman with large breasts wearing red lipstick and a fashionable bra leaning over the bonnet of a car. The woman and the car are inseparable, woven together in a single form. This is one of a series of works that examine the visual language of the auto industry, in which the bodies of women and cars are frequently compared. Hamilton highlights the fetishization and conflation of these "objects" in the post-War economy. In its abstraction and in the subject itself, it recalls de Kooning's series of women inspired by cigarette advertisements, which shocked audiences of the early 1950s. The ghost-like lines of the female body in contrast with the definitive graphic presence of the mouth anticipates the work of Tom Wesselman. Whether or not such works condemn or celebrate fetishization is beside the point. Hamilton was picking up on a theme that persists today in auto shows and car advertisements, where scantily-dressed temptresses invite us to try the latest sports car.

Oil paint, metal foil and digital print on wood - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Towards a definitive statement on the coming trends in menswear and accessories

While the new visual language of advertising and its objectification of women was well-traversed territory, Hamilton was among the first Pop artists to make hyper-masculinity the subject of his work. Serious and hilarious at the same time, this composite image pokes fun at a range of high and low sources defining modern man in the news. The much-photographed American president John F. Kennedy appears in an abstracted astronaut helmet, a reference to his determination to win the "space race" and be the first to plant a man on the moon. The president and the symbols of his territorial ambition are surrounded by painterly marks and magazine cut-outs that appear to defy gravity, as if suspended in an uncertain orbit. Readers of Playboy would have recognized the phrase "trends in menswear and accessories" as the title of the magazine's fashion column. Hamilton's addition, "Towards a definitive statement," lends a mock-academic tone to the title, as if it were a philosophical treatise, calling attention, perhaps, to the directionless nature of existence, despite the media's relentless push for male decisiveness and domination.

Paint and printed paper on wood - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Interior

While teaching in Newcastle, Hamilton found on the floor of his classroom a film still from Shockproof, a 1949 movie directed by Douglas Sirk, a German director well-known for his Hollywood melodramas. Hamilton was immediately taken with the careful composition of the image and the atmosphere of foreboding it created, and created this screenprint. Like so many of Hamilton's images, it is comprised of a selection of photographs and advertisements from American magazines. Like Hamilton's earlier collage of an interior, Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing? (1956), it depicts the figure ensconced within a matrix of consumer products, with no space for the eye to rest. The constantly exhausted state within which the consumer exists, despite all these labor-saving devices, is part of Hamilton's overarching message.

Hamilton later described the original film still as "ominous, provocative, ambiguous; a confrontation with which the spectator is familiar yet not at ease." His collage has a similar effect, creating a sort of forced perspective which causes the vanishing point to move depending on where the viewer is focusing their gaze. The vibrant Pop colors of the bottom left provide a strong contrast with the black-and-white photograph of a woman from a fashion plate and the somehow sinister image of long ghostly curtains on the right hand side.

Screenprint on paper - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

My Marilyn

This screenprint is composed of a series of images of Marilyn Monroe that Hamilton discovered soon after her death in 1962. The print is made up of photographic proofs, some of which have been unmercifully crossed out, reproducing markings made by the actress herself with the addition of some painterly brush strokes created by Hamilton. Hamilton discovered that Monroe would always ask to see photographs that were taken of her, and would mark them up to indicate which ones could be used, which could be improved through retouching and which had to be scrapped completely. Hamilton was fascinated by these markings made by the actress, describing them as "brutally and beautifully in conflict with the image."

Moved by Monroe's apparent urge to erase the photographs of herself, Hamilton's work reveals a more personal side to the actress; this version of Monroe is distinctly alien from the colorful, commercial presence summoned by Andy Warhol a couple of years earlier. Hamilton explained his own take on Marilyn's psychology in the following way: "there is a fortuitous narcissism to be seen for the negating cross is also the childish symbol for a kiss; but the violent obliteration of her own image has a self-destructive implication that made her death all the more poignant. My Marilyn starts with her signs and elaborates the possibilities these suggest." The work also reveals a more personal side to Hamilton, and contrasts sharply with the absurdist irony of his earlier images. While on one level the expressive marks are a parody of Abstract Expressionism, the symbolism of this screenprint, and the inclusion of "My" in the title, points to a deeply personal level of autobiographical symbolism. Hamilton's own wife had been killed in an auto accident in 1962, the same year as Marilyn's death.

Screenprint on paper - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Cover design for The Beatles' White Album

Richard Hamilton is well-known in some circles for his design for the 1968 album entitled The Beatles, but usually referred to as the "White Album." His design was revolutionary because of its simplicity. In contrast to the overloaded aesthetic of his earlier images, this record sleeve is completely white, and features only the words "The BEATLES" embossed slightly and set typographically off-center. Each album was also stamped with an individual serial number. Hamilton later claimed that he wanted to create "the ironic situation of a numbered edition of something like five million copies."

Hamilton's design contrasts strongly with the exuberantly colorful and busy cover for Sgt. Pepper designed by Hamilton's student, Pop artist Peter Blake. Perhaps because Blake's cover is so deeply inspired by Hamilton (it is much more "Hamiltonesque" than the White Album cover), Hamilton rebelled against his own style, choosing simple lines for the White Album that make it unlike most of the Pop art produced in this era, including Hamilton's other work, and more like Minimalism.

As a limited-edition print circulated to millions of individuals (everyone who owns a copy of this album owns an "original" Richard Hamilton print), however, it is very much in keeping with the democratic aims of the Pop art movement. Apart from being one of the greatest albums of all time, The White Album is a true cross-over between visual and musical culture. It is a work of art and an everyday object that has become part of popular culture in its own right. Through this, Hamilton bridges the gap between art and design, high and low culture, and mass production and individuality.

Album cover - Apple Core, London

Swingeing London 67 (f)

This painting by Hamilton is based on a photograph he found in a newspaper. It shows the Rolling Stones' Mick Jagger and the notorious art dealer Robert Fraser handcuffed together and attempting to hide their faces from the media. The photograph was taken when the pair were being driven to court after they had been arrested and would soon be tried and convicted for drug possession. Fraser's art gallery was the acknowledged center of the swinging '60s scene in London, and was also where many Pop artists such as Hamilton exhibited.

The title plays with the term "Swinging London", frequently used to describe the anything goes experimental mood embraced by Fraser, Jagger, and Hamilton himself, and the "swingeing" punishment settled on by the judge ("swingeing", British slang, means "severe" or "drastic"). The painting demonstrates the fundamental clash between the permissive social culture and the traditional establishment in late 1960s England.

In its use of press photography and its choice of celebrities and criminals, Swingeing London 67 (f) anticipates the work of Gerhard Richter and other conceptual artists who returned to painting in the 1980s and 90s.

Acrylic on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Biography of Richard Hamilton

Childhood

Richard Hamilton was born into a working class family in Pimlico, London, where his father was a driver at a car dealership. As a child, Hamilton later recalled, "I suppose I was a misfit. I decided I was interested in drawing when I was 10. I saw a notice in the library advertising art classes. The teacher told me that he couldn't take me - these were adult classes, I was too young - but when he saw my drawing he told me that I might as well come back next week." A couple of years later, he remembers, he was producing "big charcoal drawings of the local down and outs." Although he never finished high school, Hamilton began attending evening art classes when he was 12 years old and was encouraged to apply to the Royal Academy. On the merit of these early pieces, he was accepted into the Royal Academy the age of 16. However, in 1940 the school shut because of the outbreak of World War II. Hamilton, too young to be enlisted to fight, spent the War making technical drawings.

Early Training

In 1946 the school reopened, and Hamilton returned to the Royal Academy. He recalls, however, that by that time "it was run by a complete mad man, Sir Alfred Munnings, who used to walk about the place with a whip and jodhpurs. It was scary." Before long he was expelled for failing to comply with the school's regulations and for "not profiting from the instruction." The rescinding of his status as a student meant he was eligible to be called up for National Service; he was subsequently "dragged screaming" to join the Royal Engineers, where he served out his compulsory two years.

In 1948, he was accepted into the Slade School of Art, where he studied painting under William Coldstream. Within two years he was exhibiting his work at the Institute for Contemporary Arts in London, where he also designed an exhibition on Growth and Form in 1951, which was opened by Le Corbusier. During this period, Hamilton became friendly with many of the artists involved with the ICA at this point, most notably Eduardo Paolozzi. He was present at the meeting of the Independent Group in 1952 when Paolozzi showed some of his collages made using imagery from American magazine advertising. These very early Pop art works were to inspire Hamilton to take the movement further and to create the iconography of Pop art that subsequently became so famous.

Mature Period

In the 1950s Hamilton was a particularly important member of the Independent Group who met at the ICA in the 1950s. He took on a number of teaching posts, including at Central Saint Martins, London, and Kings College, Newcastle. In 1956, he was instrumental in defining the aims of "This is Tomorrow", the seminal exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery now considered the beginning of the British Pop art movement. A year later, Hamilton wrote down his interpretation of Pop, which was subsequently taken as the key definition: "Pop art is: Popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and Big Business."

Following the acclaim surrounding "This is Tomorrow," Hamilton was offered a teaching position at the Royal Academy of Art, London. There he taught and encouraged artists including Peter Blake and David Hockney, who were to follow in his line of British Pop art.

Hamilton's wife, Terry, was killed in a car accident in 1962. Devastated by the loss, Hamilton traveled to the US in the hope of finding some distraction. He had become increasingly interested in the work of Marcel Duchamp, and he visited a large Duchamp retrospective in Pasadena. He met Duchamp there, and they struck up a friendship. In 1966, Hamilton organized the first significant retrospective of Duchamp's work in Europe at the Tate Gallery, London. He later described the world-famous artist as "the most charming person imaginable: kind and clever and witty. Eventually I became one of the family. His wife, Teeny, was fond of me. We were fully bonded."

Hamilton also played a major role in establishing the relationship between Pop art and the burgeoning British Pop music scene. Bryan Ferry, later the founder of Roxy Music, was one of his pupils in Newcastle. Through him he befriended Paul McCartney, who asked him to design the cover for the Beatles' White Album in 1968.

Late Period

In the 1970s, Hamilton started a relationship with Rita Donagh, a painter whom he had taught in Newcastle. He later described her as "a favorite student of mine." His work began to focus on print-making processes and he also worked in collaboration with other artists, creating, for example, a series of works with the German artist Dieter Roth.

He also increasingly began to experiment with new technologies, using the tools of television and eventually computers to create works. In the 1980s, he was asked to be part of a BBC television series called "Painting with Light," which saw a series of artists use the technology of the Quantel Paintbox to create art. This was computer graphics software used in the television industry, and Hamilton continued to use it for the rest of the decade.

The same decade saw a new concern for the plight of Northern Ireland, and he made several large works depicting the Troubles. This was partly prompted by Rita Donagh's Irish heritage and connections, and they held a joint exhibition of their work in 1983. The couple finally married in 1991. He worked less productively in the last couple of decades of his life, but left behind a significant body of works when he died in 2011.

The Legacy of Richard Hamilton

Nearly every artist involved in the first wave of British Pop was shaped meaningfully by Hamilton's vision for the future of the movement. His impact on his British pupils Peter Blake and David Hockney is especially evident, but he also left his mark on the American Pop artists such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, whom he got to know and occasionally collaborated with when he visited the United States during the 1960s. His flair for public spectacle, genuine love of kitsch, and irreverent approach to cultural icons lives on in the work of Young British Artists of the 1990s, among them Damien Hirst, who describes Hamilton as "the greatest."

Influences and Connections

Useful Resources on Richard Hamilton

- Richard Hamilton (Tate Modern Catalogue)Our PickEdited by Mark Godfrey

- Richard HamiltonBy Benjamin H. D. Buchloh and Michael Bracewell

- Richard Hamilton (October Files)By Hal Foster

- Richard Hamilton - Swingeing London 67 (f) (Afterall)By Andrew Wilson

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI