Summary of Eduardo Paolozzi

Eduardo Paolozzi was a prolific and inventive artist most known for his marriage of Surrealism's early principles with brave new elements of popular culture, modern machinery and technology. He was raised in the shadows of World War II in a family deeply affected by the divisive nature of a country involved in conflict, which birthed his lifelong exploration into the many ways humans are influenced by external, uncontrollable forces. This exploration would come to inform a vast and various body of work that vacillated between the darker and lighter consequences of society's advancements and its so-called progress. On the one hand, he would create abstract sculptures, which were dark and brutal in both material and form, portraying the idea of man as a mere assemblage of parts in an overall machine. On the other hand, he would create collages, brighter in nature that reflected the way contemporary culture and mass media influenced individual identity. Some of these collages, with their appropriation of American advertising's look and feel would inspire the future Pop art movement.

Accomplishments

- Paolozzi's early love of American culture and the collecting of its paraphernalia would lead him to make collages that were credited for launching the Pop art movement. He was the first to appropriate images from advertisements to create work representative of the shinier, happier lifestyles that were touted in American magazines and media.

- Paolozzi was fascinated by the relationship between humans and machinery and often depicted biomorphic forms in his work as demonstrative of both. He incorporated metal parts such as nuts, bolts and bits of scrap into figurative forms to create rudimentary albeit cohesive new representations of the body, demonstrating the influences of progress and technology, subliminally enforced upon an individual's identity. The figures reflected a communal inner angst.

- Surrealism and Cubism influenced Paolozzi greatly and strains of each can be seen throughout his work, regardless of medium, in the way he continued to pair disparate imagery, disjointed forms, and subconscious ephemera.

Important Art by Eduardo Paolozzi

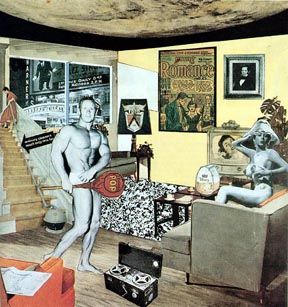

I was a rich man's plaything

This collage was made by Paolozzi as part of a series called "Bunk," composed of images from American magazines, given to Paolozzi by American ex-soldiers in Paris. A bunk can be seen to mean two things: the shell-like bed soldiers in service sleep on or a synonym for "nonsense." Both cases conjure the ideas of soldiers, stationed far from home, perusing periodicals in the privacy of their sleeping quarters at night in order to fantasize, or gaze nostalgically, about a seemingly more normal life back home, lured by the glossy pages of a magazine.

The piece includes the cover of a magazine called "Intimate Confessions," which features a voluptuous woman who, it is implied, spills her secrets inside the magazine. The inclusion of the cherry pie posits a tongue in cheek wink to the similar treatment of women and food in what was becoming new visual language in American advertising after World War II. The woman is faced with a hand holding a gun, which has fired the cartoonish word "pop!" An airplane with a propaganda-type message of jolly patriotism flies in the lower left corner alluding to the disconnect between the manipulations of mass media and the realities of day to day life, which at this time for Paolozzi were steeped in a country dealing with the more gloomy aftermaths of a difficult war.

Paolozzi was fascinated with American culture as a boy, perhaps as a way to escape a contrasting life at home, which from very early on was steeped in the notions of man being vulnerable to the workings of an overarching government. Looking toward brighter, shinier culture as a pastime was a worthy escape mechanism and this series explored this practice by compiling an image very much like the advertisements being used to sell certain ideal versions of a once removed lifestyle.

It was the first of its kind and resonated greatly within the current circle of British artists who were equally looking outward to America with its slick and robust confidence to cull their images and ideas on direct opposition to the stale tradition of art in their own country. This is considered to be the first use of the word "pop" in art of this type, and is credited for launching the Pop art movement when Paolozzi finally shared it with artists from the Independent Group in 1952. His work was original, crude and rudimentary with dog-eared and dirty cuttings on an uncleaned piece of wood. But it would become a key source of inspiration to more polished work by artists such as Richard Hamilton and Andy Warhol working in the fresh, new genre.

Collage - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Dr Pepper

This work by Paolozzi was also made as part of his "Bunk" series, drawing inspiration from Surrealist and Dadaist collage works, such as those of Max Ernst and Hannah Hoch. Paolozzi cut colorful images from advertisements he found in American magazines and assembled them to create a montage of the blossoming American consumer culture. He included cartoon and photographed images of attractive women being used to market products, domestic appliances and cars which became the symbols of a post-War boom, and the branded "Dr. Pepper" soft drink.

The compilation of colorful images meant to sell a happy existence that could be available to all was alluring to Paolozzi because rationing was still in place in Britain in 1948, and economic conditions were hard in a country on the verge of bankruptcy. He was looking at American consumerism from an outsider's perspective, implicitly highlighting the differences between the two countries. He was fascinated by the medium, and wrote "where the event of selling tinned pears was transformed into multi-colored dreams, where sensuality and virility combined to form, in our view, an art form more subtle and fulfilling than the orthodox choice of either the Tate Gallery or the Royal Academy."

Collage - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Two Forms on a Rod

This tabletop bronze sculpture is an abstract composition made up of two unexpected shapes hanging from a pole between two supporting pillars. A degree of symmetry creates a visually balanced whole. However, a feeling of discomfort is created by the strange forms, which seem to have been impaled on the rod that suspends them. The imagery, although emphatically abstract, hints at sexual forms in the existence of the short inner rods which seem to reach toward each other for interaction, asking the viewer to question their visual associations in a way that is typical of Surrealist art.

The work clearly shows the influence of the Surrealist group Paolozzi became familiar with in Paris at this time, especially Alberto Giacometti. Although Giacometti's artistic style had moved on from Surrealism by the late 1940s, Paolozzi is looking back to the earlier aesthetic of the movement from the 1920s and 1930s and offering his own interpretation of Surrealist ideas.

Bronze - National Galleries of Scotland

Cyclops

The title and eye-like wheel on the figure's head make reference to the Cyclops, a one-eyed giant of Greek mythology. In Homer's Odyssey, the Cyclops Polyphemus is powerful but his single eye is also vulnerable, and he is tricked and blinded by the clever Odysseus. Paolozzi's figure is similarly complex; it is both seeing and unseeing, and it is both imposing and melancholic. Its composition in bronze, pockmarked and riddled with holes, make it appear as if it is rusting or decaying, a common theme seen in his warped depictions of the human head. Cyclops can be read as an allegory for man in the modern age of nuclear weapons; reduced from the giant of the classical world to a dilapidated and incomplete state, made up of machine components and the tools of industry.

The semi-abstracted figure was created using the lost-wax technique, a sculptural process favored by members of Surrealist circles including Salvador Dali. To produce the work, Paolozzi pressed metal items into softened clay before pouring in wax and finally casting the figure in bronze. This innovative use of found items took Paolozzi's collecting instincts (first seen in his collages) in a new direction. The artist once claimed of works like this, "I use a collage technique in a plastic medium."

Paolozzi made a number of robot-like, human-sized works during the mid-1950s. He was fascinated with robots for much of his life, perhaps as an allegory for man within a system beyond his control. They owe something to the existential beings produced by Giacometti, with the addition of Paolozzi's own vision and interests. The works don't have a feel of a bright future; they are a vision of a "used future" (a term that came to some prominence at the time). And yet, these emotionless collections of parts do seem to have stability and pride in them, a quality that seems closer to an attempt to prolong life, rather than the opposite.

Bronze - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

The History of Nothing

To produce this work, Paolozzi created a series of collages, which he then combined as if they were slides for a film. He applied a similar collage technique to the cutting and editing of the film fragments, splicing together disparate images from books, magazines and popular culture. The resulting effect is one of constantly shifting images that flash up as if by visual association, often throwing up unlikely pairings, such as James Joyce and the silhouette of a dancer made up of machine parts.

In this way, Paolozzi invites the viewer to form a narrative based on the disparate images, playing with ideas of the human subconscious. He called the film an "homage to Surrealism" and claimed it was intended to demonstrate the "schizophrenic quality of life." For most of the images, Paolozzi chose older photographs or images from magazines, creating a sense of nostalgia that runs throughout the film. The work is distinctly witty, both in its semi-philosophical title and in the juxtaposition of its imagery, pointing to an important facet of Paolozzi's work and personality in which the external consistently informs the personal. It also demonstrates his constant commitment to experimentation and new media.

Film - British Artists' Film and Video Study Collection, London

The Silken World of Michelangelo

The Silken World of Michelangelo is part of a series that Paolozzi produced as an unbound book called Moonstrips Empire News. It is made through the screen-printing process, a technique that began to interest Paolozzi during the 1960s. He was intrigued by the mechanics of the process and wanted to explore its associations with the commercial printing of advertisements. It is a medium that was being explored by American Pop artists such as Andy Warhol, and Paolozzi's pop art screen-prints run in a similar vein, working with a consciousness of the Pop art movement that he helped to initiate.

However, Paolozzi's work, by this point had moved beyond Pop art's usual remit of advertising and publicity; instead he combined these images with visual references to art history and also to mechanical processes. The inclusion of both a Mickey Mouse figure (on the left) and a negative photograph of Michelangelo's David (to the right) prompts the audience to question issues of artistic reproduction and appropriation. Disney's Mickey Mouse represents popular consumer culture, whilst the David recalls a golden age of original artistic production. The implication is that the Michelangelo work had been reproduced so many times and in so many contexts that it had become devoid of its original meaning and now represented another facet of mass-production and consumerism.

Paolozzi asks us to explore the relationship between human beings and the mass-production afforded by technological innovations that had become common by this time. While still rejoicing in the colors and imagery of American consumer culture, Paolozzi also feared for the state of humanity in the nuclear age of technological weapons. His screen-prints created a more lively juxtaposition to his darker sculptural works as he concertedly worked to process his feelings of both the dark and light aspects of progress in the contemporary world.

Screenprint - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Mosaics for Tottenham Court Road Tube Station

One of Paolozzi's largest projects began when he was commissioned to design 1000 square meters of mosaics for the London Underground tube station at Tottenham Court Road. Paolozzi was concerned with how commuters would react to the mosaics. He asked, "what happens when people pass quickly through the station on the train? Will people relate to the metaphors I sought in connection with life above ground - cameras, music shops, saxophones, electronics?" The design starts at the top of the main escalator, drawing the viewer's eye onward as they continue their journey. This work was intended to be seen on the move, and his imagery is similarly dynamic, switching between abstract and figurative forms.

The result was so well received that an exhibition was subsequently organized at the Royal Academy entitled "Eduardo Paolozzi Underground". The president of the RA at the time claimed that Paolozzi's mosaics proved that "art can transform our everyday surroundings and need not be restricted to the narrow confines of art galleries." This was a key concern for an artist who took his inspiration primarily from the visual language of advertising or abandoned machine parts, rather than from the historical works to be found in museums. Sadly, however, part of the mosaic was lost when Transport for London redeveloped Tottenham Court Road station in 2015. Nevertheless, the majority of the work continues to be seen by the general public on a daily basis.

Mosaic made of vitreous, smalti and piastrelle - Tottenham Court Road Tube Station, London

Biography of Eduardo Paolozzi

Childhood

Eduardo Paolozzi's parents immigrated to Scotland from Italy where the artist was born in Leith, an area north of Edinburgh. They owned an ice cream parlor and as a child, Paolozzi enjoyed collecting cigarette packet cards, usually featuring Hollywood stars or military vehicles such as airplanes, prompting a life-long fascination with both American culture and the relationship between people and machinery.

His father admired Mussolini and sent his son to Fascist summer camps in Italy. When Italy joined the Second World War in 1940, the British interned Paolozzi along with his male relations, marking them as enemy aliens. During the young artist's three months in prison, his father and grandfather (who had the unusual name of Michelangelo) were to be transported to Canada. On the way, a German U-Boat sunk their ship and they drowned. This resulted in Paolozzi's deep distrust of war and of the British government, which remained throughout his life.

Early Training

After he was released from internment, Paolozzi studied at the Edinburgh College of Art for a period of time before being conscripted into the army. He feigned insanity in order to be released early, and enrolled at the Slade School of Art in Oxford, where he studied for the duration of the war. While there he enjoyed drawing the anthropological collections at the Pitt-Rivers museum, demonstrating an early attraction to non-classical art forms. When the school's premises were moved back to London, he encountered the work of Pablo Picasso, which was to have a huge influence on his style. His first solo show, consisting of primitivist sculpture and Cubist-inspired collage, was held at London's Mayor Gallery in 1947; it was a great success and everything exhibited was sold.

Later that same year, Paolozzi moved to Paris, where he got to know a host of Surrealist artists who were becoming very well-known. They included Alberto Giacometti, Jean Arp, Constantin Brancusi, Georges Braque and Fernand Leger. With roots in the improvisational nature of Dada, Surrealism evolved the idea of using elements of surprise in unexpected juxtapositions and non sequitur. This was a key impressionable moment in the young artist's career and in the late 1940s he made various sculptures in the Surrealist vein that reflected his deep interest in images of modern machinery. He also made a number of collages based on appropriated images from magazines he gathered from American soldiers who were based in the area on training programs after the Second World War. These collages represented a culmination of all his prior artistic influences. They married his obsessions with American culture, Surrealism's utilization of random forms and imagery, and graphic design industry-inspired layouts into bold and visually fresh compositions, which would later mark the inception of the British Pop art movement. Although much of Paolozzi's later work exhibits evidence of the influence of this formative time, his period in Paris didn't prove as satisfactory as he had hoped and he only stayed for two years.

Mature Period

On returning to London in 1949, Paolozzi's artistic identity blossomed as he immersed himself into multiple fields reflecting his prolific and wide-ranging creative interests. A decade of devout practice and production followed, evolving a career that bridged the worlds of fine art, academia and commercial art production. He started to teach at the Central School of Art and Design and established a studio in Chelsea, sharing a space first with painter Lucian Freud and then with sculptor William Turnbull. He also got to know Francis Bacon, whom he admired for his innovative approach to painting.

In 1951 he married textile designer Freda Elliot and the couple moved to a small remote village in Essex. He established a company with his friend, the experimental photographer Nigel Henderson. The firm was called Hammer Prints Ltd and specialized in silk-screened textiles and wallpaper. The collaboration lasted for seven years and produced a successful range of design products, often inspired by the duo's artistic practices. Paolozzi was very successful by this point, and was able to rent a studio in London. He lived in the capital during the week and returned to his countryside cottage on the weekends. This rigorous schedule ended up having a detrimental effect on his marriage, leaving his wife feeling isolated and lonely. The couple's three daughters were sent away to boarding school and were rarely at home.

During the 1950s, Paolozzi created many sculptures that concentrated on an anguished human form, perhaps harkening back to the chaos of his childhood wrapped in the horrors of war. He began exploring the relationship between machine and the body in this work, often incorporating metal parts directly into the wax maquettes, which would then be cast in bronze.

A seminal moment in his career came in 1952, when he began showing his collages made earlier in Paris to his peers. One piece in particular, I Was a Rich Man's Plaything (1947) was a great inspiration to the future group of British Pop artists and was indeed the first piece that literally showcased the word "pop" in its composition. This led him to get involved with The Independent Group of burgeoning British Pop artists and in 1956 he collaborated on a section of the This is Tomorrow exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, which gave the new genre its first noted stage. It was during this time that he became friendly with other artists also making work that borrowed from popular American culture including Peter Blake and Richard Hamilton.

During the1960s, Paolozzi further evolved his endless fascination with the relationship between industry and art. He developed new ways of creating sculpture by collaborating with various engineering firms and experimenting with new materials such as aluminum. During this time, he took on a series of teaching posts around the world, including stints in Hamburg and California. He remained extremely productive, creating a huge quantity of art in a variety of media. However, toward the end of the decade his star began to wane, perhaps as a result of his constant curiosity that led him to vacillate wildly away from a singular identity in his work, making his artistic voice hard to pin down. His retrospective at the Tate Gallery in 1971 was panned by critics and through much of his career his popularity never exceeded a very general level of appreciation.

Late Period

Paolozzi's experimentations continued throughout the 1970s as he began to use wood in a number of abstract relief pieces that utilized geometric and biomorphic elements. His career received a new lease of life in 1974 when he was invited to work in Berlin and his reputation was revived in 1979 when he was invited to become a member of London's Royal Academy. In the 1980s the human head became a regular subject in his sculpture and collage, often shown mutilated or haphazardly affixed.

Paolozzi remained committed to teaching, both in Cologne and Munich, where he worked between 1981 and 1994. It was reported that during his post at the Munich Academy he would frequently sleep on a camp bed in his messy studio. He went on to make a large number of works for public bodies both in Germany and in the UK. These include several large-scale sculptures and mural mosaics for the underground station at Tottenham Court Road in London. In 1988, to Paolozzi's surprise, his wife Freda asked for a divorce, to which he agreed. The following year he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II, becoming Sir Eduardo Paolozzi.

The Legacy of Eduardo Paolozzi

Paolozzi was particularly concerned with his reputation and how the public would go on to view him after his death. In 1994 he donated a large body of his works to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in an attempt to enshrine his future reception.

Paolozzi's impression on the psyche of contemporary sculpture, particularly in its cobbling together of various industrial parts and found materials in rudimentary fashion, can be seen in many modern artists. This is evident in the compository work of Peter Voulkos, the fragmented figures of Stephen De Staebler, and many others working in the metamorphosis of rubbish or the discarded.

He will particularly be remembered for the early collage works, which were important in inspiring the British pop art movement. This would eventually spur the International Pop art movement from which superstars like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg sprang.

Influences and Connections

-

![Surrealism]() Surrealism

Surrealism -

![Cubism]() Cubism

Cubism -

![Art Brut and Outsider Art]() Art Brut and Outsider Art

Art Brut and Outsider Art ![Modern Sculpture]() Modern Sculpture

Modern Sculpture