Summary of David Hockney

David Hockney's bright swimming pools, split-level homes and suburban Californian landscapes are a strange brew of calm and hyperactivity. Shadows appear to have been banished from his acrylic canvases of the 1960s, slick as magazine pages. Flat planes exist side-by-side in a patchwork, muddling our sense of distance. Hockney's unmistakable style incorporates a broad range of sources from Baroque to Cubism and, most recently, computer graphics. An iconoclast obsessed with the Old Masters, this British Pop artist breaks every rule deliberately, delighting in the deconstruction of proportion, linear perspective, and color theory. He shows that orthodoxies are meant to be shattered, and that opposites can coexist, a message of tolerance that transcends art and has profound implications in the political and social realm.

Accomplishments

- Like other Pop artists, Hockney revived figurative painting in a style that referenced the visual language of advertising. What separates him from others in the Pop movement is his obsession with Cubism. In the spirit of the Cubists, Hockney combines several scenes to create a composite view, choosing tricky spaces, like split-level homes in California and the Grand Canyon, where depth perception is already a challenge.

- Hockney insists on personal subject matter - another thing that separates him from most other Pop artists. He depicts the domestic sphere - scenes from his own life and that of friends. This aligns him with Alice Neel, Alex Katz, and others who depicted their immediate surroundings in a manner that transcends a particular category or movement.

- Hockney was openly gay, and has remained a staunch advocate for gay rights. In the context of a macho art scene that dismissed "pretty color" as effeminate, Hockney's bright greens, purples, pinks, and yellows are declarative statements in support of sexual freedom.

- In actively seeking to imitate photographic effects in his work, Hockney is a forerunner of the Photorealists. He is also a heretic among purists who feel that painting should rely only on the artist's direct observations from nature. Though not universally accepted, Hockney's research into the history of art has shown that Old Masters, from Vermeer to Canaletto, frequently used the camera obscura (an early form of camera) to enhance their optical effects. If the revered Old Masters could use cameras, he implies, why can't we?

The Life of David Hockney

Britain's beloved David Hockney has a career of breaking taboos and leading the avant-garde - to the point of being recognized as the most important artist to revitalized painting. And in his eighties, Hockney continues to be active and to make headlines.

Important Art by David Hockney

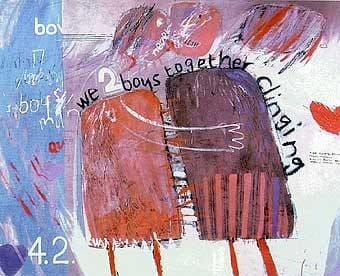

We Two Boys Together Clinging

This early work by Hockney shows no sign of the slick landscapes or carefully observed characters that he would later develop. It is one of the first, however, to address homoeroticism, an important theme in his work. In a composition that resembles a child's drawing, two figures kiss and embrace. Stylized, blocky forms and scrawled words offer symbols as opposed to descriptions of the encounter. Small horizontal lines of pigment run from one figure to the other, representing the erotic charge between them. A sketchy swathe of blue hints at a sense of place.

Hockney's semi-abstracted figures and muted color palette recall those of Jean Dubuffet, a stylistic preference indicative of the challenge of finding a way to represent forbidden feelings. At a time when homosexual activity was still illegal in both the U.S. and in Britain, the representation of an erotic act between two men was unusual and potentially risky. The title is a direct quote from Walt Whitman, master of homoerotic poetry, and the image was inspired by a report of a climbing accident in a newspaper that read "Two Boys Cling to Cliff All Night." This unintended double meaning delighted Hockney, who had a crush on the British pop singer, Cliff Richard. These sources in popular culture and classic poetry offered the artist a way to address same-sex relationships in a way that didn't resort to caricature.

Oil on board - Southbank Centre, London

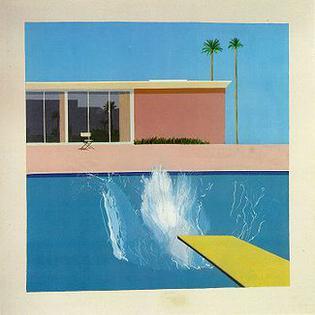

A Bigger Splash

Hockney painted this seminal work while at the University of California in Berkeley. A Bigger Splash was created as the final result of two smaller paintings in which he developed his ideas, A Little Splash (1966) and The Splash (1966). A Bigger Splash is a considerably larger work, measuring approximately 94 x 94 inches. Hockney was one of the first artists to make extensive use of acrylic paint, which was then a relatively new artistic medium. He felt that as a fast-drying substance it was more suited to depicting the hot, dry landscapes of California than traditional oil paints. He painted this work by stapling the canvas to his studio wall.

In A Bigger Splash, Hockney explores how to represent the constantly moving surface of the water. The splash was based on a photograph of a swimming pool Hockney had seen in a pool manual. He was intrigued by the idea that a photograph could capture the event of a split second, and sought to recreate this in painting. The buildings are taken from a previous drawing Hockney had done of a Californian home. The dynamism of the splash contrasts strongly with the static and rigid geometry of the house, the pool edge, the palm trees, and the striking yellow diving board, which are all carefully arranged in a grid containing the splash. This gives the painting a disjointed effect that is absolutely intentional, and in fact one of the hallmarks of Hockney's style. The effect is one of stylization and artificiality, drawing on the aesthetic vocabulary of Pop art and fusing it with Cubism.

He said in his autobiography, "I love the idea first of all of painting like Leonardo, all his studies of water, swirling things. And I loved the idea of painting this thing that lasts for two seconds: it takes me two weeks to paint this event that lasts for two seconds."

Acrylic on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

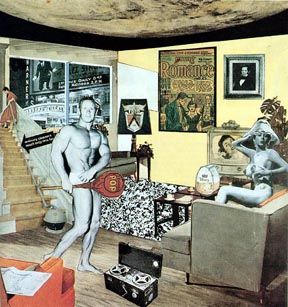

American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman)

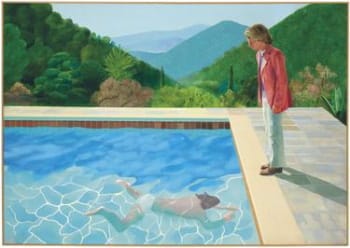

While Hockney paints a broad range of subjects, some of his most masterful compositions are his portraits of the late 1960s. These offer unrivaled, almost cinematic, insights into the mood and culture of this transitional decade in American history. Here are Fred and Marcia Weisman, art collectors and friends of Hockney, who appear outside their residence as if stepping outside to greet a neighbor. Hockney's blinding, saturated palette mimics the light of Southern California. The Weismans are surrounded by their prized art possessions, among them an imposing modernist sculpture in a niche, and a totem pole that looks like it could be a third member of the family.

Dry humor pervades all elements of the composition. The viewer half expects to see the vertical elements - the stiff couple and their belongings - blast off like space ships into the blue sky. The threat of the surreal lurking in this picture underscores the consistent relationship between Pop art and older movements. Also noteworthy is the manner in which the poses transgress traditional gender norms. Marcia, a full-figured matron in a robe held closed with one arm, bares her teeth, and strikes a sensual pose that is both gracious and confrontational. Fred, the man of the house, stands stiffly with his fists clenched, and is literally marginalized as he is pushed to the left-hand side.

Acrylic on Canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

A Visit with Christopher and Don, Santa Monica Canyon

For this view of the "Santa Monica Canyon", Hockney draws on the language of Cubism, a strong influence on his artistic style throughout his life due to his deep admiration for the work of Picasso. For this work, he extends the Cubist visual vocabulary through his use of a rich color palette borrowed from the Pop art movement.

The composition measures 6 x 20 feet, a scale normally reserved for grand subjects from history or the bible. It consists of two canvases side-by-side. And yet it is a subject normally reserved for smaller canvases, a household interior, in which Hockney combines representations of the California home with seaside views and portraits of himself at work to the left and right. There are no conventional architectural or painterly boundaries between the different elements of the composition. Hockney uses flat areas of color and texture to create distinct spaces.

This work makes use of a multi-point "reverse" perspective, meaning that it contains several vanishing points that extend out towards the viewer rather than converging on a distant horizon. In the spirit of Cubism, Hockney offers more than one viewpoint, and extends the perspective outwards, drawing the viewer into the scene that is so big, one feels one might step right into it.

Oil on two canvases

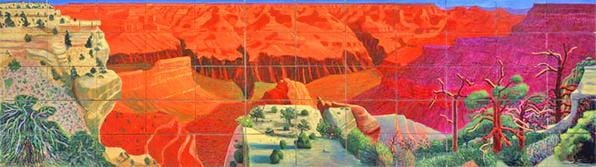

A Bigger Grand Canyon

Hockney began photographing the Grand Canyon in 1982, aiming "to photograph the unphotographable. Which is to say, space. [T]here is no question that the thrill of standing on that rim of the Grand Canyon is spatial. It is the biggest space you can look out over that has an edge." Not many artists attempt to paint The Grand Canyon. One reason is that it is so large, no indicator of depth, distance, or scale can convey it. The other is that the 19th-century painter Thomas Moran produced what is considered by many to be the definitive version: a spectacular, monumental canvas so detailed, so complete, and so naturalistic that it set an unsurpassable standard. Unfazed by this precedent and directly inspired by Moran's famous view, ("intrigued to see how another artist grappled with representing the same vast, heroic space" according to the National Museum of American Art) Hockney produced A Bigger Grand Canyon - which is even larger than Moran's canvas. Sixty small canvases join together to create one large view representing just a portion of the canyon. Hockney is poking gentle fun at tourists with cameras, artists with easels, and the absurdity of attempting to map a three-dimensional experience onto a two-dimensional plane.

Oil on canvas

Winter Timber

While many of Hockney's best-known works were inspired by photographs, this work was painted in front of the motif, at the corner of an old Roman road in Yorkshire, near his birthplace. The purple palette renders the landscape contemporary and eternal, like a computer-generated fairytale. It is one of the largest in a series of timber and "totems", as Hockney calls the lone tree stumps depicted in these representations. Throughout his career, Hockney has been interested in returning to tradition in order to examine it, but with an almost scientific detachment that places the viewer off-center. This view, presented across fifteen canvases, has two paths of perspective leading down the two roads through the woods. This means that the visual plane contains two vanishing points, rebuking the one-point perspective that has characterized Western art since the Renaissance. It also transgresses the single perspective of the camera lens, the point of view that has come to define how we see the world in photographs. The painting's two vanishing points lead outward toward us, creating a kind of double vision that heightens the kaleidoscopic, hallucinatory effect of the piece.

Oil on 15 canvases - Guggenheim, Bilbao

A Bigger Message

Created relatively late in Hockney's career, A Bigger Message is a culmination of a series of works by Hockney inspired by The Sermon on the Mount, Claude Lorrain's 1656 painting. Lorrain was one of Hockney's heroes - a French Baroque landscape painter (in English, simply "Claude"), known for revolutionizing the genre and basing his work on observation, Claude has had a strong effect on Hockney's landscapes. In order to create the painting, Hockney spent three weeks digitally cleaning the painting by Claude on his computer. Through this process, Hockney got to know the composition better, and created a thoroughly contemporary way of painting; rather than working from life, or even from the original work, his inspiration came from a mediated, doctored version of the Old Master's work.

Hockney is fully aware that many art enthusiasts would frown on this process, and fully intends to tweak the nose of tradition. He is also, however, following in the footsteps of another renegade, Picasso, who painted Cubist versions of Velazquez's Las Meninas based in part on reproductions from newspapers and magazines. Distance from the original allows the artist to create his own spin on the scene. Hockney takes his palette not from Claude but from Pop art, and from his own earlier depictions of the Californian and Yorkshire landscapes. He draws more attention to the human figures in the foreground of the image, and represents the mountain as an oversized red rock, imbuing the scene with a distinct sense of drama absent from the original.

Oil on 30 canvases

Biography of David Hockney

Childhood

One of five children, David Hockney was born into a working-class family in Yorkshire, northern England, in the industrial city of Bradford. His father, a conscientious objector during the Second World War, "had a kind heart" remembers Hockney. "He thought there should be justice in the world". He also romanticized the ideals of the Communist party in Russia. While adopting his father's anti-war stance, Hockney remained resistant to ideologies and hierarchies. As a schoolboy, Hockney says of himself, "I was always quite serious, but cheeky." Art was something he knew he wanted to do very early in life. At his school academically promising boys were forced to drop art as a subject and so he deliberately failed his exams. Interestingly, Hockney was born with synesthesia, meaning that he sees colors as a response to musical stimuli

Early Training

At 16, Hockney was admitted to the acclaimed Bradford School of Art, where he studied traditional painting and life drawing alongside Norman Stevens, David Oxtoby, and John Loker. Unlike most of his peers Hockney was from a more humble family, and he worked tirelessly, especially in his life drawing classes, recalling: "I was there from nine in the morning till nine at night."

In 1957 he was called up for National Service, but as a conscientious objector he served out his time as a hospital orderly. It was around this time that Hockney encountered the work of Russian ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev, whose openness about his sexual identity gave Hockney the courage to reveal his own.

In 1959, Hockney went on to study at the Royal College of Art in London and was taught by several well-known artists, including Roger de Grey and Ceri Richards. His friends included R.B. Kitaj, Allen Jones, and Peter Blake. At the time, the college asked students to submit an essay along with their final work. Hockney refused, wanting to be judged solely on the basis of his art. Remarkably, the RCA, a bastion of tradition, changed its rules to allow him to graduate.

Mature Period

Hockney's first solo show, held in 1963 at John Kasmin's gallery, proved very successful. The following year he traveled to Los Angeles for the first time, where he met leading intellectual and artistic figures including Christopher Isherwood, and designer Ossie Clarke, with whom he struck up a close friendship and later traveled to the Grand Canyon. He would later be best man at Clarke's wedding to Celia Birtwell, of whom he would paint and draw many portraits. Over the following few years, he resided almost permanently in California, teaching at various universities including Berkeley and UCLA, but also traveling extensively around the US and Europe. During this period he painted some of his best-known works, including A Bigger Splash (1967). He also began to design productions for the ballet, opera, and theater. While his synesthesia didn't play much of a role in most of his artmaking, it did influence his set design work. He first listened to the musical score for each production, and then based his designs off of the colors he saw.

In California during the 'swinging 60s', Hockney embraced the mood of experimentation, exploration, and iconoclasm. At a time when homosexuality was still illegal in the U.S. and Britain, Hockney's open love affairs and unapologetic attitude attracted the attention of newspapers and magazines. He met and started a long-term relationship with Peter Schlesinger, who also frequently acted as his model, a relationship that lasted from 1966 to 1971. Of his unconventional lifestyle and experimentation with drugs during this period, Hockney has commented: "you can't have a smoke-free bohemia. You can't have a drug-free bohemia. You can't have a drink-free bohemia." In 1973, Hockney moved to Paris, where he lived until 1975. By the mid-1970s, he was famous. 1974 saw a large traveling retrospective of his work, and a film about him directed by Jack Hazan. In 1976 Hockney published his autobiography and in 1978, he purchased property in Los Angeles' Hollywood Hills, where he maintains a residence and studio to this day.

The AIDS crisis of the 1980s changed the art world forever, and had a particularly profound impact on Hockney who recalls "the first person to die of AIDS that I knew was in 1983, and then for ten years it was lots of people. If all those people were still here, I think it would be a different place." A retrospective of Hockney's work was due to take place at London's Tate gallery in 1988. He threatened to cancel it in protest of anti-homosexual legislation being proposed in Britain at the time.

Late Period

The 1990s constituted a very productive period for Hockney, with a huge number of retrospectives and exhibitions around the world. In 1991, he began a relationship with John Fitzherbert, a former chef, which lasted for the next 25 years. One of his most important large-scale works, A Closer Grand Canyon, was completed in 1998. From 2000-01 he researched and wrote a book about the Old Masters, developing a theory that these artists made use of the camera far earlier than previously thought. For his research, Hockney assembled photocopies of Old Master paintings, from Byzantine Art to Van Gogh, on a huge wall in his LA studio. While Hockney's theory met with significant resistance, it has gained widespread support from the art history community. In 2002, Hockney moved to the Yorkshire seaside town of Bridlington. In the same year, he sat for 120 hours for a portrait painted by Lucian Freud. In return, Freud sat for four hours for him.

Hockney had a stroke in 2012, which for a while impaired his speech. Much to his relief, "the stroke didn't affect my drawing, and that's the most important thing." Only a few months later, one of his assistants, Dominic Elliot, died in Hockney's home. He had taken cocaine and ecstasy and drank a bottle of drain cleaner. Elliot had been in a relationship with Hockney's former partner John Fitzherbert, who was still living with him. At the high-profile inquest, Hockney was required to give evidence that the death was not a murder. In 2015, he decided to sell his mother’s Bridlington house and moved back permanently to Los Angeles.

The Legacy of David Hockney

In 2011 a poll of British art students rated Hockney as the most influential artist of all time. His work has played a crucial role in reviving the practice of figurative painting. Chuck Close, Cecily Brown, and film director Martin Scorsese (especially the aesthetics of Taxi Driver (1976)) are among the artists inspired by Hockney. Hockney, still prolific, continues to reinvent himself, embracing contemporary technology. His most recent series of works was produced on an iPad. Despite his widespread fame, he remains an iconoclast, steadfastly refusing to accept institutional authority, even some of the highest honors, turning down an invitation to paint a portrait of the Queen (Hockney was "very busy" and couldn't make it), and a knighthood in 1990 (although he was awarded, and accepted, the Order of Merit in 2012). "I don't have strong feelings about the honours system" Hockney has remarked, "I don't value prizes of any sort. I value my friends."

Influences and Connections

Useful Resources on David Hockney

- David Hockney: The Biography, 1937-1975By Christopher Simon Sykes

- David Hockney: The Biography, 1975-2012By Christopher Simon Sykes

- A Bigger Message: Conversations with David HockneyBy Martin Gayford

- Life of David Hockney: A NovelOur PickBy Catherine Cusset

- True to Life: Twenty-Five Years of Conversations with David HockneyOur PickBy Lawrence Weschler

- Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old MastersBy David Hockney

- Spring Cannot Be Cancelled: David Hockney in NormandyOur PickBy David Hockney and Martin Gayford

- David Hockney: A Yorkshire SketchbookBy David Hockney

- A History of Pictures: From the Cave to the Computer ScreenOur PickBy David Hockney and Martin Gayford

- Hockney PicturesBy David Hockney

- David Hockney’s Dog DaysBy David Hockney

- David Hockney: A Bigger PictureOur PickBy Margaret Drabble and Marco Livingstone

- David Hockney. A Chronology. 40th Anniversary EditionOur PickBy Hans Werner Holzwarth

- Hockney’s Portraits and PeopleOur PickBy Marco Livingstone and Kay Haymer

- David Hockney: Moving FocusBy Helen Little

- David HockneyOur PickBy Chris Stephens and Andrew Wilson

- David Hockney: A Bigger ExhibitionBy Richard Benefield et al.

- CameraworksBy Lawrence Weschler

- Hockney/Van Gogh: The Joy of NatureBy Hand den Hartog Jager

- Modernists and Mavericks: Bacon, Freud, Hockney and the London PaintersOur PickBy Martin Gayford

- Hockney on Photography: Conversations with Paul JoyceBy Paul Joyce

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI