Summary of Avant-Garde Art

Originating in military terminology, the phrase "avant-garde" was adapted to apply to the work of artists - and then taken on by artists themselves - in order to indicate the socially, politically, and culturally revolutionary potential of much modern art. From the Realism of Gustave Courbet to the genre-defying multimedia experiments of the Fluxus movement, the term "avant-garde" has been associated with groups of artists - and sometimes single individuals - who sought to fly in the face of acceptable standards of artistic taste and to define new paradigms of creativity. In some movements this emphasis on the new was tied to a radical political and social agenda, a desire to tear down and replace social systems that were seen as somehow bound up in mainstream aesthetic standards.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Although the idea of the avant-garde suggests a preoccupation with breaking new ground, in almost all cases this did not reflect a standalone interest in novelty but was underpinned by a desire to give a clearer impression of "reality". For Gustave Courbet, that meant depicting the harsh working lives that were banished from the academic canvas; for the Impressionists it meant capturing the effects of light on the retina at the moment of perception; for the Constructivists it meant depicting the invisible scientific forces at work under the surface of visible reality. But in all cases, the desire to render reality in a newly precise way was the underlying aim.

- The idea of the avant-garde has traditionally been beholden to two interpretations. On the one hand, it is seen as inextricably linked to a radical social or political program, so that transgressive art becomes the vehicle for transgressive social and political activity. On the other hand, avant-garde art has been seen as the domain of pure stylistic experiment, unfettered by social concerns of any kind. These two definitions have their own accompanying chronologies, hierarchies, and critical rubrics, which are often strikingly at odds with each other.

- The birth of the avant-garde was also the birth of the idea of "anti-art": that art could stake its value partly on undermining, subverting, or mocking pre-existing notions of artistic value. From the Impressionists, with their quick, loose brushwork, to Marcel Duchamp with his readymades, avant-garde art always drew some of its impact from its evident disregard for existing norms, and its ability to generate an impression of non-art, even ugliness.

- Avant-garde art has, traditionally, never just been described as avant-garde, but has also been associated a particular movement: from Realism to Impressionism to Expressionism to Cubism and so on. Part of the avant-garde artist's identity and purpose has traditionally involved defining a clear and programmatic set of aims for their work, generally also associated with a tight-knit group of associates or comrades, which would form the basis for their creativity. As such, the origins of avant-garde art are also the origins of the contemporary notion of the art 'movement.'

The Important Artists and Works of Avant-Garde Art

The Painter's Studio

This painting, depicting the artist seated with brush and palette in hand as he contemplates the landscape he has been painting, is intended as a metaphor for the life of the artist. Courbet subtitled the work: "a real allegory summing up seven years of my artistic and moral life." The artist is framed by a nude model, representing a muse and a small boy symbolizing innocence, while the room is filled with various recognizable figures. Charles Baudelaire, the noted poet and critic, is seated on a desk reading in the far right, among the cultural elite, while on the left are various figures from all aspects of society. The artist said he intended to represent "society at its best, its worst, and its average." As he further explained, "it's the whole world coming to me to be painted. On the right, all the shareholders, by that I mean friends, fellow workers, art lovers. On the left is the other world of everyday life, the masses, wretchedness, poverty, wealth, the exploited and the exploiters, people who make a living from death."

A pioneer of Realism, Courbet was to define the movement by saying, "Realism is democracy in art." As the art critic Linda Nochlin puts it, "he saw his destiny as a continual vanguard action against the forces of academicism in art and conservatism in society." After the 1855 Paris World Fair's jury refused to exhibit this work, Courbet opened The Pavilion of Realism, his own exhibition, where he also presented The Burial at Ornans, which had also been rejected. Aided by his patron, Alfred Bruyas - also portrayed in The Painter's Studio - Courbet's exhibition represented an act of defiance to the official venues. It also prefigured the later development of the Salon des Refusés and all of subsequent 20th century exhibitions created by avant-garde movements in defiance of traditional venues.

Nochlin notes the importance of this work to the avant-garde: "it is not until seven years after the 1848 Revolution that the advanced social ideals of the mid-nineteenth century are given expression in appropriately advanced pictorial and iconographic form, in Courbet's The Painter's Studio. ...Courbet's painting is 'avant-garde' if we understand the expression, in terms of its etymological derivation, as implying a union of the socially and the artistically progressive." In summary, Nochlin describes The Painter's Studio as "a crucial statement of the most progressive political views in the most advanced formal and iconographic terms available in the middle of the nineteenth century."

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe

Édouard Manet's shocking landscape work, showing two fully clothed men taking lunch on the grass with a nude woman, famously caused a scandal when it was displayed in the 1863 Salon des Refusés, an exhibition for works rejected by the official Paris Salon. Although Manet never fully aligned himself with the avant-garde imperatives of the Impressionist painters, a younger group of artists who saw him as something of a mentor, with works such as Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, he certainly broke down many of the doors that later avant-garde artists would stream through in their quest for the new.

This painting was avant-garde in two senses, rejecting both the stylistic tenets of the era and its bourgeois social and moral norms. In the first case, the large size of the canvas was at odds with its apparently mundane, modern subject-matter, the image presented on a scale normally reserved for historical and mythological scenes. The tonal qualities of the piece were also peculiar: brash and artificial-seeming, the harsh light and shadow jarring with the apparent outdoor setting (Manet famously never shared the Impressionists' enthusiasm for painting en plein air) and drawing the eye to the massed white flesh of its central subject. And much of the background brushwork seemed informal, almost half-finished, as if the composition were drawing attention to itself as such: a mere conceit or fiction, discarded on a whim before completion.

But it was the subject-matter of the work that was truly shocking. Nude women were an acceptable component of academic art provided they were presented in the context of a historical scene, such that the nudity was somehow at a moral and intellectual distance. Manet's scene presented a nude body without any of the veneer of historical narrative, which made it more real and shocking to its audiences. With this gesture, he paved the way for the increasingly unabashed focus on (female) nudity and moral transgression that defined the avant-garde endeavors of coming decades.

Oil on canvas - Musée D'Orsee, Paris

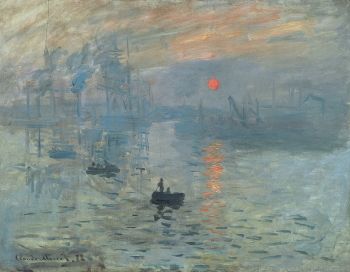

Impression, Sunrise

Claude Monet and the Impressionists formed the first avant-garde movement to achieve international success and fame. In this work, from which the term "Impressionism" was indirectly derived, Monet captures a sunrise in the port city of Le Havre, the family home to which he had returned for a holiday. The elemental blue and orange color palette, combined with the quick, spontaneous brushwork, is designed to convey the visual impression made by the scene at a particular moment in time, rather than picking it out in all its detail. This revolutionary approach was not, in Monet's case, accompanied by radical social views, but it forced him into a position of oppositionality to mainstream culture and the art-world that was quintessentially "avant-garde."

Monet had met a number of other young painters in the studio of the painter Charles Gleyre in 1862, including Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Frédéric Bazille, and Alfred Sisley. These artists, joined by others such as Berthe Morisot and Camille Pissarro, formed the backbone of the Impressionist movement, which practiced its ideas for many years - under the informal tutelage of the older painter Édouard Manet - before finding commercial success. After their continual rejection by the Paris Salon, Monet and his fellow Impressionists formed their own society to fund and exhibit their work. Impression, Sunrise was amongst those displayed in its first exhibition in 1874, where it attracted the ire of many critics, including Louis Leroy, whose ironic play on the term "Impression" in its title formed the origin of the movement's name.

Though the method of depicting the natural world that Monet and his compatriots developed is now very familiar to us, at the time it was revolutionary to relay the details of a scene in such a quick and intuitive way, as it was to paint on-site, or en plein air, as Monet did in order to create Impression Sunrise. The formal advances of Impressionism, and its necessary opposition to received social and cultural norms, set the terms for the development of avant-garde art over the coming century and a half.

Oil on canvas - Musée Marmottan Monet

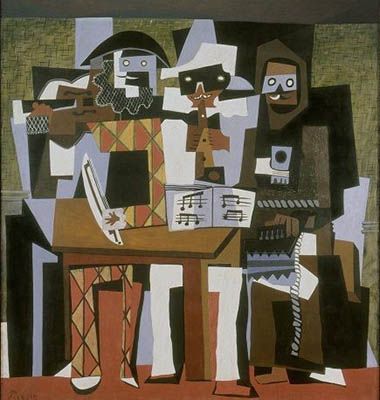

The Three Musicians

Pablo Picasso, one of the founders of the Cubist movement, had been creating avant-garde artworks since the 1900s. However, this painting from 1921 evokes especially effectively the idea of the radical social milieu with which the avant-garde was often associated. The large canvas depicts three musicians, two of them portrayed as figures from Commedia dell' Arte. The Harlequin figure on the right is thought to represent Picasso who often portrayed himself as the trickster character of the Italian theater, while the central figure in white is thought to be Guillaume Apollinaire, the prominent critic of avant-garde art and close friend of Picasso's. Dressed as Pierrot, the figure plays a musical instrument but conveys melancholy alienation, On the right, dressed as a monk, is the figure of Max Jacobs, the poet and close friend, who had joined a Benedictine community at St.-Benoît-sur-Loire. In effect, the painting is partly a nostalgic evocation of the artist's youth.

Beginning with his Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), a radical proto-Cubist work, Picasso became a leading avant-garde figure, as he and Georges Braque developed Cubism, working through its iterations of Early Cubism, Analytic Cubism, and Synthetic Cubism. As a result, as the contemporary art curator Jessica Stewart notes, "Cubism is one of the most well-known avant-garde movements...Figures were broken into geometric shapes, colors were brightened and simplified, and collage was incorporated for an innovative result that continues to shape art today. In fact, looking at a timeline of art history, Western visual culture can be split clearly into two pieces - before and after Cubism."

There are two versions of this painting, and both are interpreted as marking the end and culmination of Picasso's Synthetic Cubism phase. The figures are painted but resemble paper cutouts, pieced together like jigsaw puzzles out of varying broad planes of color and patterned paper. Spending the summer with his family at Fontainebleau, Picasso painted a series of paintings, including these two, which also referenced Commedia dell' Arte imagery and the influence of theatrical design as he had been working with the noted theatrical producer and director Sergei Diaghilev for the Ballets Russes.

Oil on canvas - The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

Black Square

This famous work consists of a black square against a white background. Examined more closely, the work reveals the fine cracks of the surface, as the pigment has aged, as well as brushstrokes and a fingerprint. However, it was the way that the work reduced the picture plane to a single, elemental geometric form that made it both a radical departure into abstraction and a singular moment of the avant-garde. The painting was exhibited at The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 in St. Petersburg in 1915 as if it were a Christian icon, elevated and displayed in the corner of the room as was customary in Russian homes. Malevich described the work as "the first step of pure creation in art," the "embryo of all potentials." The black square became the implicit building block in his subsequent paintings.

Whereas the Cubists had broken down the centuries-old law of the picture plane, Malevich saw avant-garde art as leading the way to a new culture by freeing itself from the obligation to represent reality altogether. In his 1915 essay, "From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Realism in Painting," Malevich argued for the "the liberation of objects from the obligations of art," describing Suprematism - the movement which he led - as an evolution of Cubism, which had not gone far enough. "A painted surface is a real, living form... The forms of suprematism, the new painterly realism, already testify to the construction of forms out of nothing, discovered by intuitive reason. The cubist attempt to distort real form and its breakup of objects were aimed at giving independent-life of its created forms." The wider context for Malevich's work was the movement of Russian Constructivism, and the atmosphere of revolutionary ferment in the years preceding the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. In reducing the picture plane to the absolute minimum of formal elements, and in tying his work to a revolutionary social moment, Malevich offered with his Black Square an exemplary instance of avant-garde invention.

Art critic Rosalind McKever notes that: "the argument may seem academic, but time is central to avant-gardism as an arbiter of quality. The military term refers to those sent ahead of the ordinary troops, those going first, who will inevitably be followed by the masses. The value in an avant-garde artwork comes, in part, from it being first. Malevich's Black Square is a perfect example, not least because Malevich himself dated the work, which is thought to have been painted in 1915, to 1913, confirming the importance of being first. When Malevich repeated the work in the 1920s as geometric abstraction had taken hold; the aesthetic value of the later versions may be barely distinguishable, but their art-historical and potentially therefore their market values are wholly different."

Oil on canvas - Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

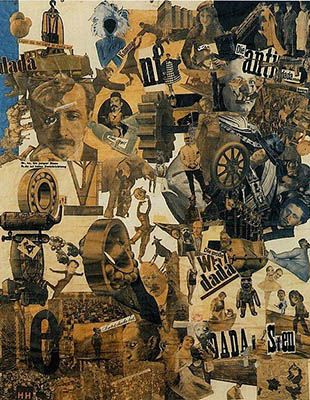

Cut with a Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany

This pioneering collage by the Dada artist Hannah Höch uses clippings from newspapers and magazines to convey the absurdity and corruption of contemporary German culture. As Anahid Nersessia notes, for Höch "the collage is a highly suggestive act of bricolage, a piecing together of materials that come to represent the fragmented nature of the culture from whose debris they are drawn." The work exposes the cultural polarities and fissures of post-war Berlin. Among the clippings are recognizable images of artist Käthe Kollwitz, silent film star Pola Negri, and political thinkers and leaders, including Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin. In the lower right corner, a small map of Europe depicts the countries where women have the right to vote.

As art historian Heidi Hirschl Orley writes, Höch was "known for her incisively political collages and photomontages (a form she helped pioneer)", in which she "appropriated and recombined images and text from mass media to critique popular culture, the failings of the Weimar Republic, and the socially constructed roles of women." Höch's innovative use of photomontage to fundamentally challenge social, cultural, and aesthetic traditions made her a leading figure of early Dada, and an exemplary avant-garde figure in the more socially engaged sense of the term. In Berlin in 1920, she exhibited this work, as well as others, at the First International Dada Fair in 1920, where her work was acclaimed, even though her male colleagues had originally attempted to discourage her from participation.

The use of photomontage became widely influential and was adopted by subsequent movements throughout the 20th century, from Surrealism to Fluxus. As Heidi Hirschl Orley notes, "Höch's bold collisions and combinations of fragments of widely circulated images connected her work to the world and captured the rebellious, critical spirit of the interwar period, which felt to many like a new age. Through her radical experimentations, she developed an essential artistic language of the avant-garde that reverberates to this day."

Cut paper collage - National Gallery, State Museum of Berlin

Number 1

This monumental painting, with its energetic swirl of rhythmically applied layers and lines of industrial paint, exemplifies Jackson Pollock's "drip painting" technique, which gave birth to the movements of Abstract Expressionism and Action Painting in North America in the 1940s. Placing the canvas on the floor and flinging paint onto it with a variety of implements, Pollock sought to achieve a kind of unity with the work-in-progress to muster the emotive energy needed to complete it: "on the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting."

Clement Greenberg said of this work that "beneath the apparent monotony of its surface composition it reveals a sumptuous variety of design and accident." Abstract Expressionism, and particularly the work of Pollock, was viewed by Greenberg as the pinnacle of avant-garde art, as it had broken through to autonomous abstraction, divesting itself of all social concerns. By this reading, Pollock's work exemplifies avant-garde art in its formal rather than conceptual sense. Contemporary art historian Donald Burton Kuspit echoes Greenberg's reading with a more critical tone, noting that "formal abstraction initiated by Picasso and the Cubists reached its extreme in the emergence of the avant-garde American art, Abstract Expressionism, in the 1940s."

Pollock's approach reflected his view that "new needs need new techniques." Many subsequent avant-garde artists - and indeed many previous ones - followed a similar dictum, but Pollock's drip painting approach was particularly akin to the contemporary Japanese movement of Gutai. Founded by Shozo Shimamoto and Jiro Yoshihara, this group created experimental works that blurred the boundaries between performance, painting, and installation art. As gallerist David De Buck said: "they all wanted to break the traditional brush and move more into action painting and painting a different style, so Shimamoto actually threw vessels, glass bottles, cups filled with paint onto the canvas." This and countless other examples indicate the significance of Pollock's work in defining the course of the avant-garde across the latter half of the twentieth century.

Enamel and metallic paint on canvas - The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

Theater Piece No. 1

While teaching at Black Mountain College, an experimental art school in North Carolina which was then a hub of neo-avant-garde activity, the composer John Cage created this score for a multimedia performance, which was to include a number of leading avant-garde artists and writers, including the choreographer Merce Cunningham, the pianist David Tudor, the poet Charles Olson, and the painter Robert Rauschenberg. Cage orchestrated the piece but chance was to play a determining role in what was simply called "The Event."

Trained as a composer, John Cage is famous for his chance and graphic scores, which are stripped of the conventional notations of the musical page and invite spontaneous responses from performers. Amongst his most famous scores is 4'33" (1952), which consists of a set of blank staves. Cage himself gives a memorable recollections of the Black Mountain College performance given the same year: "at one end of the rectangular hall, the long end, was a movie, and at the other were slides. I was on a ladder delivering a lecture which included silences, and there was another ladder which M.C. Richards and Charles Olson went up at different times... Robert Rauschenberg was playing an old-fashioned phonograph that had a horn, and David Tudor was playing piano, and Merce Cunningham and other dancers were moving through the audience. Rauschenberg's pictures [the White Paintings] were suspended above the audience...They were suspended at various angles, a canopy of paintings above the audience."

The work, subsequently referred to as "the first happening", exemplified the concerns of the Neo-avant-garde, and was considered to be a prototype for the multimedia performance art of Fluxus and other movements, as it incorporated prose, poetry, live music, dance, recorded music, art works, film, and photographic slides. Later teaching at the New School in New York City, Cage influenced Allan Kaprow, who pioneered the Happening as a form, as well as other performance artists including Al Hansen and George Brecht. Cage's work was also important to the development of Conceptualism, and Minimalism, and he became an important (though controversial) figure within classical music, his introduction of chance into composition influencing Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre, Boulez, and Philip Glass, among others.

Imagen de Yagul

This color photograph shows the artist, nude and covered with foliage and white flowers, as she lies in an indigenous pre-Columbian tomb made by the Zapotec people. The foliage that obscures her upper body seems animated, as if vigorously growing out of her form. She becomes anonymous, a figure of both death and fecundity.

This work was part of Mendieta's Silueta Works in Mexico 1973-1977, a series containing over 200 pieces, all of them involving her laying on the ground, making an imprint with her body, or merging with the elements, such as the foliage in this photograph. The series is considered a pioneering work of several avant-garde movements, including Land Art, Body Art, and Performance art. As art historian Laura Roulet writes, Mendieta's work "encompasses the full range of avant-garde 1970s movements - conceptual, performance, earthwork, feminist, and identity art...Much of Mendieta's output involved negotiating and transcending boundaries, some the result of geographic displacements, others imposed by an art world that still categorized work by gender, ethnicity, media, First World versus Third World, and as high or low art."

Mendieta described the series as follows: "I have been carrying on a dialogue between the landscape and the female body (based on my own silhouette) I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature). Through my earth/body sculptures I become one with the earth I become an extension of nature and nature becomes an extension of my body." Her work's innovation was connected to both aesthetic and cultural change, as she stated, "My art is the way I reestablish the bonds that tie me to the universe."

Chromogenic print - San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Beginnings

The Origins of the Phrase

Originally, "avant-garde" was a French military term for what would be called in English the vanguard of an army. However, its first application to art precedes by some decades the emergence of any distinctly avant-garde art movements. The coinage has generally been attributed to the French social theorist Henri de Saint-Simon. In his book Opinions litteraires, philosophiques et industrielles (Literary, Philosophical, and Industrial Opinions) (1825), published in the year of his death, Saint-Simon wrote: "It is we artists who will serve you as avant-garde . . . the power of the artists is in fact most immediate and most rapid: when we wish to spread ideas among men, we inscribe them on marble or on canvas...What a magnificent destiny for the arts is that of exercising a positive power over society, a true priestly function, and of marching forcefully in the van[guard] of all the intellectual faculties...!"

However, due to a lack of authorial identification methods at the time, and the close working relationships between Saint-Simon and his disciple Olinde Rodrigues, scholarly theories about the true origins of this concept have varied. Many propose that the idea first appears in Rodrigues's essay "'Le artiste, le savant et l'industriel" ("The Artist, the Scientist, and the Industrialist"), also published in 1825.

In any case, it is clear that, while the idea of avant-garde art subsequently became identified with radical aesthetics and techniques, Saint-Simon and his disciples were indifferent to such concerns. For them, avant-garde art was that which served the concepts and forces of social progress, "exercising a positive power over society." This definition, focusing upon and even requiring a concern for social progress, exerted a continuing force on avant-garde artists and critics even as their methods became more rarefied.

Precursors

The idea of avant-garde art germinated in an era of social unrest, and was originally one of a number of competing theories to define and address it. However, Saint-Simonism, emphasizing the importance of the industrial class and science in renewing society, had become a particularly dominant force by the early 1800s.

The unique distinction of Saint-Simon's theory was that it expanded the concept of the working class to include scientists, businesspeople, bankers, and managers. This expansion became a kind of template for later including artists of all disciplines as agents for social change. Saint-Simon's ideas became influential only toward the end of his life, as a number of disciples, including Barthélemy Prosper Enfantin, carried them forward into the mid-19th century. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the originators of Communism, later claimed Saint-Simon as a "utopian socialist," citing his ideas as inspiration for their own; Saint-Simon also influenced the development of anarchism by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.

The French Revolution of 1848

The concept of avant-garde art took more distinct shape across the early-to-mid decades of the 19th century in France, especially between the July Revolution of 1830 and the French Revolution of 1848. This eighteen-year period was marked by political turmoil, movements for social reform, and counter forces of suppression. In 1848, revolt and rebellion occurred throughout Europe, from Scandinavia to Italy to Germany and Hungary. Amongst its causes were widespread famine and poverty, the inequality of industrialization, and the forces of restrictive government. The Revolutions of 1848 were also called the Spring of Nations or the Springtime of the Peoples, reflecting the democratic and egalitarian impetus of the movement.

Among revolutionary thinkers art was seen as a vital force for social change, and the military origins of the term "avant-garde" established a clear connection with the cause of the rebels taking to the streets. Fourierism, named for its founder Charles Fourier, became a particularly influential strain of utopian socialist thought during the 1848 Revolution and the Paris Commune, and one which emphasized the value of the arts. The Fourierist art critic, Gabriel-Désiré Laverdant wrote in his De la Mission de l'art et du rôle des artistes: salon de 1845 (On the Mission of Art and the Role of Artists: Salon of 1845) that "Art, the expression of society, manifests, in its highest soaring, the most advanced social tendencies: it is the forerunner and the revealer. Therefore to know whether art worthily fulfills its proper mission as initiator, whether the artist is truly of the avant-garde, one must know where Humanity is going, know what the destiny of the human race is ..."

The art historian Linda Nochlin states that, following the 1848 Revolution, "a new dawn for art [was] predicated upon the progressive ideals of the February uprising. At the time the most important art journal of France, L'Artiste, in its issue of March 12, 1848, extolled the 'genius of liberty' which had revived 'the eternal flames of art'...and the next week, Clément de Ris, writing in the same periodical... maintained that 'in the realm of art, as in that of morals, social thought and politics, barriers are falling and the horizon is expanding'."

Gustave Courbet

The Realism of Gustave Courbet and his associates is often cited the first avant-garde art movement. As the social theorist George Katsiaficas notes, "Courbet...and Realists in the 1840s like Honoré Daumier...and Jean-François Millet... were some of the earliest advocates of the idea that art could play an emancipatory role in society." For art historian Linda Nochlin, Courbet is "the painter who best embodies the dual implications - both artistically and politically progressive - of the original usage of the term 'avant-garde."

Katsiaficas notes the particular importance of Courbet's monumental canvas The Stonebreakers, which "long served as a standard for political avant-gardism." Painted in the year following both the failed revolutions of 1848 and the publication of Marx and Engels' The Communist Manifesto, it seemed to distil the zeitgeist of the era and its disappointments, emphasizing the harsh realities of working-class life. Critics of the time, such as Théophile Thoré, celebrated Courbet's work in the very process of calling for democratic reform, noting that: "art changes only through strong convictions, convictions strong enough to change society at the same time."

The Salon des Refusés of 1863

During the mid-to-late 19th century, France's annual state-sponsored "salons" - large exhibitions held at Paris's Académie des Beaux Arts since 1648 - remained important markers of public taste. Each year, a selection of what was deemed the most accomplished work submitted by contemporary artists was selected by the judges for display. But by the 1860s, the salons were seen by the most progressive artists to have become outmoded, blind to the changing tides of artistic and political culture sweeping across France and Europe.

In 1863, almost two thirds of the works submitted to the Salon was rejected, in what seemed a clear sign that the jurors were unable to countenance avant-garde art. Indeed, many avant-garde artists were actively courting salon rejection. Courbet said of his The Return from the Conference (1863), which was amongst the refused works: "I painted the picture so that it would be refused. I have succeeded. That way it will bring me some money." Other (very famous) rejected works included Édouard Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (1863) and James Abbott McNeill Whistler's Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl (1861-62). Emperor Napoleon III established the Salon des Refusés ("Salon of the Refused") in response to the public protest that followed the rejection of such a huge swath of the submitted work. This is often taken as a pragmatic marker for the birth of the avant-garde as a dominant force in French art, and ultimately across Western culture as a whole.

Impressionism

Notwithstanding the advances of Courbet and the Realists, Impressionism was the first avant-garde art movement to gain widespread influence and fame. Coming together in the early 1860s, the Impressionists were a group of artists, including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, and Alfred Sisley, who began mounting their own exhibitions in intentional defiance of the official Salon.

Calling themselves the Société Anonyme des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs et Graveurs (Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers), the group held their first exhibition in 1874. Developing a radical technique involving loose and spontaneous brushwork, painting outside to capture the optical effects of light, and favoring subjects from everyday reality over history and mythology, the Impressionists were avant-garde in both technique and subject matter. However, while they built upon Courbet's Realism, they shifted the concept of the avant-garde towards an emphasis on formal and aesthetic innovation rather than social or political reform. Dubbed "Impressionists" in a negative review by the art critic Louis Leroy, the group took up the name defiantly, in a move that would be replicated by subsequent avant-garde movements such as the Fauvists and the Cubists.

Post-Impressionists

Though they began as Impressionists, a number of late-19th-century artists, such as Georges Seurat, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Paul Cézanne, took radically divergent and individual artistic paths that profoundly influenced subsequent avant-garde art. Seurat played a leading role in establishing Neo-Impressionism, developing a scientific approach to composition based on color theory also dubbed "pointillism." This movement, also pioneered by Paul Signac, was responsible for stunning works such as Seurat's A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-86), and influenced a swathe of later avant-garde artists, from Piet Mondrian to Henri Matisse to Bridget Riley.

While Seurat was refining and heightening the effects of Impressionism, Paul Cézanne had moved from Paris to take up a quiet and simple life in Provence. Though a contemporary of the first generation of impressionists, Cézanne developed a wholly original style that would be primarily influential on the development of Cubism in the 1900s. Attempting to isolate and emphasize the elemental forms in landscapes and still lives, he began to realize that objects could be depicted from multiple perspectives on single canvases. Picasso would later dub Cézanne "the father of us all," while Braque, Picasso's fellow founder of Cubism, was to note that "in Cezanne's work we should see not only a new pictorial construction but also...a new moral suggestion of space."

Paul Gauguin was one of a number of painters working in the wake of Impressionism who adapted the movement's emphasis on quick, bold brushwork to create more stylistic or emotive effects. For Gauguin, this meant moving away from the mottled effects of Monet or Sisley towards bold blocks of bright, often hyperreal color, a style dubbed "Cloisonnisme" after the patches of colored glass in stained-glass window. Later, the term "Synthetism" was coined to describe a similar range of work produced by artists such as Émile Bernard, Paul Sérusier and Maurice Denis, many of whom were also connected with the Nabis movement. In the 1890s Gauguin moved to Tahiti where he developed a singular body of work evoking the colorful flora and culture of the island.

Vincent Van Gogh would become, after his death, the most famous of all late-nineteenth-century French painters. But during his lifetime he was just one of a number of artists attempting to move beyond the optical effects of Impressionism to create emotive and evocative landscapes and still lives. Van Gogh's striking tonal range and highly stylized and ever-evolving brushwork, as well the strong emotional charge of his work, eventually set his work apart. Van Gogh would be an enormous influence on the development of German Expressionism and Fauvism during the early-20th century, and of Abstract Expressionism and Neo-Expressionism in the mid-20th century. He is now remembered as much for his short, tragic life - the quintessential example of an avant-garde artists neglected during his lifetime and revered after his death - as for his remarkable body of work.

Concepts and Trends

Avant-garde Art Movements

Avant-garde art was synonymous with the idea of the "movement" as the primary concept for understanding the development of art during the 20th century. As contemporary philosopher Alain Badiou has noted, "More or less the whole of twentieth-century art has laid claim to an avant-garde function."

Sometimes an avant-garde movement consisted - at least initially - of only a few artists, as in Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque's Cubism or Delaunay and Sonia Delaunay's Orphism (though both movements attracted more practitioners.) In contrast, movements such as Dada and Surrealism became international. Despite their variance in range and importance, avant-garde art movements often positioned themselves in opposition to previous orthodoxies, whether these were aesthetic standards or social and cultural norms. Small galleries, art collectors, and art critics played an important role in advancing such movements. For instance, the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire became a leading advocate for a number of avant-garde movements including Cubism, Salon Cubism, Orphism, and Surrealism. In fact he is credited with naming some of these movements.

Galleries and Museums

An essential characteristic of avant-garde art was its rejection of previous social and aesthetic orthodoxies. As such, its initial success often depended upon a small group of critics and gallerists willing to fly in the face of those orthodoxies. As the art critic Rosalind McEver notes, "avant-garde is a noun as well as an adjective. It refers to groups of artists and writers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, specifically, those making and distributing art in a different way to their contemporaries; artists who self-consciously created 'isms', were promoted by themselves or critics in little magazines and showed and sold their work in private galleries or artist-led exhibitions." For instance, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler's small Parisian gallery and his exclusive representation of Picasso and Braque gave both artists financial security and served to promote Cubism. Kahnweiler's book The Rise of Cubism (1920) also became an important theoretical framework for evaluating the movement.

In 1929, the primacy of avant-garde art as an international cultural phenomenon was confirmed by the establishment of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, the first museum devoted to modern art. As the art historian Donald Burton Kuspit notes, "the founding of the Museum...was the consummate sign of the social and economic success of avant-garde art." The museum's first director was American art historian Alfred H. Barr, Jr., who described the museum and its proposed twenty exhibitions in the first two years as offering "as complete a representation as possible of the great modern masters."

Influenced by Kahnweiler, Barr also developed a schema that tracked the advancement of avant-garde art across time, from Cézanne to Cubism (which was given central importance), to abstract art. Barr's belief in educating the public about avant-garde art, as the architect Philip Johnson wrote, "persuaded an entire generation...about modern art." At the same time, as Kuspit puts it, "the power of an institution to dictate and legislate art history is clear: Barr was in effect a modern Le Burn, and the Museum of Modern Art became the avant-garde academy."

The Avant-garde and Alienation

The Romantic movements of the early 19h century were the first to emphasize the idea of the solitary and independent artist, often portrayed as a kind of Byronic hero. As Linda Nochlin notes, "the idea of the artist as an outcast from society, rejected and misunderstood by a philistine, bourgeois social order was...not a novelty by the middle of the nineteenth century."

This had developed into a more pronounced sense of social alienation by the middle of the 19th century. Nochlin adds that for mid-19th-century French writers and artists such as Flaubert, Baudelaire, and Manet, "their very existence as members of the bourgeoisie was problematic, isolating them not merely from existing social and artistic institutions but creating deeply felt internal dichotomies as well." This sense of alienation and estrangement became a noted element of avant-garde art.

Avant-garde often aspired to shock the viewer in order to create an awareness of the alienation underlying modern reality, disrupting concepts of normality or deliberately cultivate a sense of the uncanny (as in Surrealism.) Autonomous and isolated, the artist's idiosyncrasies became the subject and driving force of art. Contemporary art historian Donald Kuspit argues that by the end of the twentieth century, only the idiosyncratic was seen as authentic, as seen in his Idiosyncratic Identities: Artists at the End of the Avant-Garde (1996).

Anti-art

A logical outcome of the avant-garde artist's sense of detachment from the tastes and mores of mainstream society was a scorn for its ideals of aesthetic beauty or quality. Some such idea had always underpinned the formulations of avant-garde artists, from Courbet, with his unabashed images of working-class life, to the Impressionists, who divested themselves of the laborious composition and finishing processes of contemporary academic painters.

The idea that the artwork need not confirm to conventional ideas of artistic value arguably reached its apex during the 1910s, through the iconoclastic activities of the Dada artists. Working during an era of global warfare and revolution, when all social norms seemed to be thrown up in the air, artists such as Marcel Duchamp began to present works divested of all familiar artistic qualities, including, in Duchamp's case, even the impression that they had been created by an artist. His readymades, mass-manufactured, utilitarian objects presented as sculptures, such as a bicycle wheel and a urinal, were truly shocking during the era of their presentation, even to audiences becoming well-acquainted with the advances of Cubism.

The idea that art need not, indeed ought not to, conform to conventional ideas of beauty or artistic value underpins almost all subsequent developments in avant-garde art. Conceptual Art, one of the most dominant of the "neo-avant-garde" movements of the 1950s-70s, began from the proposition that an artwork could simply comprise the documentation of a concept, not tied to any particular object or image, let alone an aesthetically appealing one. And many contemporary artists continue to work in the wake of this development; from Joseph Kosuth's One and Three Chairs (1965) to Damien Hirst's The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991).

The Formal Versus the Conceptual Avant-Garde

The idea of the avant-garde was initially underpinned by a concept of social or political revolt. As Linda Nochlin notes, "Courbet quite naturally expected the radical artist to be at war with the ruling forces of society and at times quite overtly, belligerently, and with obvious relish challenged the Establishment to a head-on confrontation. The idea of the artist as an outcast from society, rejected and misunderstood by a philistine, bourgeois social order was of course not a novelty by the middle of the nineteenth century."

However, the identification of avant-garde art with social reform was always at odds with the financial and social aspirations of some avant-garde artists, such as the stolidly middle-class, ambitious, and apolitical Claude Monet. In their work, the connotations of "avant-garde" took on a set of more purely formal parameters, emphasizing stylistic revolution divorced from any social or political aims.

During the 20th century, the idea of avant-garde as necessarily socially revolutionary began to be challenged more forcefully. While Surrealism or Russian Constructivism had strong social programs, aiming to challenge and transform social orthodoxies, art movements such as Cubism emphasized formalism. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque's break with the centuries-long tradition of linear perspective had no overt sociological impetus.

Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the first director of MoMA, was important in ensuring that the formal view of the avant-garde held sway for much of the twentieth century, partly because he viewed Cubism as so central to the story of modern art. As the contemporary art historian Donald Kuspit notes, "in Barr's diagram of the development of avant-garde art through 1935[,] 'Cubism,' in the largest letters, has pride of place. According to the diagram, Cubism derives from Cézanne, Neo-Impressionism, and Henri Rousseau and leads directly to Suprema[tism], Constructivism, and De Stijl, finally leading to abstract art." Barr's diagram entrenched what Kuspit calls "the orthodox formal high line" in modern art, with social and political concerns banished to the margins of avant-garde programs. By contrast, German Expressionism, Dadaism, and Surrealism, movements which symbolically challenged the foundations of modern capitalist society, are, according to Kuspit, "shunted to the side" in Barr's graphic.

Over time, criticism and scholarship became sharply divided between these two approaches. The critic Peter Bürger associated the term "avant-garde" exclusively with Dada, Constructivism, and Surrealism, movements with an obvious social agenda. These, for Bürger, were the "classic avant-gardes." By contrast, the critic Clement Greenberg, favoring movements such as Cubism, and the Abstract Expressionism with which he became particularly associated, connected the avant-garde with an 'art for art's sake' approach. For Greenberg, art did not need to justify its existence on social grounds or offer any political function. This debate has continued into the contemporary era, and continues to prompt re-evaluations of previous periods.

The Avant-Garde and Science

Avant-garde artists were often inspired by scientific discoveries and incorporated technological themes and concepts into their artistic innovations. Pointillism or Neo-Impressionism, which was influenced by academic studies on light-processing by the retina, was one of the first avant-garde art movements to ostentatiously embrace scientific theory. The art historian Meyer Schapiro describes the Neo-Impressionist George Seurat as "an engineer of his paintings, analyzing the whole into standard elements...and exposing in the final form, without embellishment, the working structural members."

The Italian Futurists aggressively endorsed modern technology, as shown in Umberto Boccioni's Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), which, according to the MoMA's catalogue notes, "integrates trajectories of speed and force into the representation of a striding figure." While it is well-known that the Surrealists were influenced by Freud's discoveries of psychoanalysis, the subconscious, and the meaning of dreams, as critic Joe Ferguson noted, they were equally affected by "the new physics of Bohr, Plank, Heisenberg, and Schrödinger, as well as the Theory of Relativity by Einstein... All of this was fodder for avant-garde artists looking to turn the world on its head."

The importance of technology and science also transformed concepts of the artist and the artwork. Art historian Donald Kuspit notes, the Russian Constructivists saw themselves as "constructor technicians," as exemplified in El Lissitzky's self-portrait The Constructor (1924). Kuspit adds that "many works of avant-garde art in fact look as though they are new inventions, and many are machine-made rather than handmade." These ideas arguably reached their apex with the Concrete Art movement of the mid-twentieth century, and the idea of the artwork as divorced from the artist's emotional input was also influential on the development of Conceptual and Post-Conceptual Art later in the century.

Important Texts

Avant-Garde and Kitsch

By Clement Greenberg

Originally published in Partisan Review, 1939

In 1939, Clement Greenberg published his essay "Avant-Garde and Kitsch," which argued that the avant-garde artist attempts to create "something valid solely on its own terms, in the way nature itself is valid...something given, increate, independent of meanings, similars or originals." Later associated with Abstract Expressionism, which he championed, Greenberg's theories became the leading art-critical concepts of the era. The idea of the avant-garde was foundational to his subsequent work. He viewed the avant-garde as opposed to both academic art, of which he noted that "the same themes are mechanically varied in a hundred different works, and yet nothing new is produced," and to kitsch. The latter he defined as "popular, commercial art and literature with their chromeotypes, magazine covers, illustrations, ads, slick and pulp fiction, comics, Tin Pan Alley music, tap dancing, Hollywood movies, etc., etc."

Greenberg's theories played a leading role in separating the avant-garde from its previous connections to social issues. Defining the avant-garde artist as isolated from social concerns, he dubbed the avant-garde "the first settlers of bohemia" and argued that "once the avant-garde had succeeded in "detaching" itself from society, it proceeded to turn around and repudiate revolutionary as well as bourgeois politics." Greenberg felt that "the true and most important function of the avant-garde was not to "experiment," but to find a path along which it would be possible to keep culture moving...Retiring from public altogether, the avant-garde poet or artist sought to maintain the high level of his art by both narrowing and raising it to the expression of an absolute in which all relativities and contradictions would be either resolved or beside the point." In his subsequent essays, such as "Towards a Newer Laocoon" (1940) and "Modernist Painting" (1961), he proposed the idea of total abstraction as the fulfillment of avant-garde art.

Theory of the Avant-Garde

By Peter Bürger

Originally published as Theorie der Avantgarde by Suhrkamp Verlag, 1974

In the 1970s Peter Bürger's Theory of the Avant-Garde became so influential that two years after its publication, a volume of responses by leading art historians, artists, and critics was published. A member of the Frankfurt School, Bürger developed the idea of what he called "the historical avant-garde," which he placed during the era of 1910-40. He argued that avant-garde art represented the unification of art with everyday life: or more specifically, socially revolutionary action and expression.

Focusing on Dada, Surrealism, and the Russian avant-garde, Bürger's ideas echoed the thought of earlier avant-garde artists, such as Alexander Rodchenko, who wrote, "it is time that art entered into life in an organized fashion." Similarly, André Breton wrote that Surrealism "tends to ruin once and for all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principal problems of life."

As the critic Doug Sinsen notes, Bürger's work was challenged almost immediately for its perceived oversimplification of "the complex and multifarious phenomenon of the avant-garde." Other theorist felt that Bürger's thesis "pa[id] scant attention to the specificities of individual works and artists, [was] overly restrictive in its selection of artists and movements, and, most infamously, dismisse[d] the neo-avant-garde as a mere empty repetition of the historical avant-garde." Bürger's rejection of Neo-Dadaists was particularly controversial, and subsequently refuted by historian Hal Foster. Yet, as Sinsen notes, "Hal Foster, one of Bürger's sharpest critics, called Theory of the Avant-Garde a 'central text' on the avant-garde, and its ideas have had a lasting impact on the scholarship of the early twentieth-century avant-garde."

Other contemporary scholars have viewed Bürger's work as correctly defining the decline of the avant-garde. In 2012, Evan Mauro argued that "subsequent criticism has tended to prove Bürger right: the trajectory suggested in his Theory of the Avant-Garde has been largely accepted, and the story of the twentieth-century avant-gardes is invariably a story of decline, from revolutionary movements to simulacra, from épater le bourgeois to advertising technique, from torching museums to being featured exhibitions in them. Consensus has settled on an interpretation that has the avant-garde crashing on the reef of postmodernism sometime around 1972."

Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century

By Hal Foster

Published by MIT Press, 1996

Art historian and critic Hal Foster has played a leading role in contemporary analysis of the avant-garde. Through his work The Return of the Real, Foster aimed to refute Bürger's argument that the neo-avant-garde of the 1960s and 70s had failed, and primarily represented a repetition of the historical avant-garde. As his publisher noted, "after the models of art-as-text in the 1970s and art-as-simulacrum in the 1980s, Foster suggests that we are now witness to a return to the real - to art and theory grounded in the materiality of actual bodies and social sites. If The Return of the Real begins with a new narrative of the historical avant-garde, it concludes with an original reading of this contemporary situation - and what it portends for future practices of art and theory, culture and politics."

Burger's most recent book Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency (2015) asks what the avant-garde can mean in late capitalism. As the art critic Rachel Wetzler writes, "at a moment when the most institutionally hostile practices have been readily embraced, and when art seems given over to ballooning market values, corporate sponsorship, and blockbuster spectacle, is it possible to maintain faith in the idea of an avant-garde - or, for that matter, in the value of critique? However dire the situation may be, Foster insists that the avant-garde is not over, but perhaps more necessary than ever - not in the sense of the heroic historical avant-garde of "radical innovation" or "transgression," but an avant-garde that is "immanent in a caustic way," one that "seeks to trace fractures that already exist within a given order, to pressure them further, even to activate them somehow."

Later Developments

The Neo-Avant-Garde

The Second World War represented a kind of hiatus for the development of avant-garde art, which had continued more or less unabated since the 1870s, the most recent internationally successful example being the Surrealist movement. After the end of the Second World War and the recalibration of international politics and culture, including the US's consolidation of power as the dominant economic and social force of the era, avant-garde movements began to regroup across continents and media. Their collective endeavors are often described using the moniker "neo-avant-garde", a term particularly associated with the writing of Hal Foster and Benjamin H.D. Buchloch.

One of the striking features of the neo-avant-garde period was the spread across media and across national boundaries that defined its activities. The example of Fluxus, perhaps the quintessential neo-avant-garde movement - also often referred to as "Neo-Dada" - might serve to emphasize this idea. Fluxus had its roots in visual art and sculpture but also encompassed theatre, musical composition, literature and poetry, and social activism, resulting in activities and products that were hard to categorize within any of these boundaries. Its proponents, meanwhile, though they converged on New York during the 1960s-70s, originated from all over the world, from Lithuania (George Maciunas) to Japan (Yoko Ono). In many ways, the neo-avant-garde exemplified the era of the "global village" as defined by the media theorist Marshall McLuhan, when international travel and communication became easier, and the modes of expression found in everyday life, from billboard advertising to TV and radio, began to encompass multiple media or channels, from language to visual effect and sound.

Other significant movements variously described as neo-avant-garde include Abstract Expressionism (though this was in many ways tied to older conceptions of the avant-garde, and many neo-avant-garde artists set their stall out against Clement Greenberg's theories, which were strongly tied to the movement); Tachisme and Nouveau Réalisme; Pop Art, Op Art, Kinetic Art; Minimalism; and, perhaps above all, Conceptualism and its offshoots, which continue to define a large part of contemporary modern art practice. Other figures such as Joseph Beuys worked to a large extent apart from any one movement but produced highly significant bodies of work which might be described as neo-avant-garde.

The Death of the Avant-Garde?

In the 21st century, the question of whether the avant-garde still exists is often questioned. In a sense, the neo-avant-garde movements of the 1970s were the last to be debated and celebrated as unambiguously avant-garde. The term's relevance following the intellectually levelling effects of postmodernism - which challenged the idea that any artistic, cultural, or political position could be more viable than any other - is certainly questionable. For the philosopher Alain Badiou, "today the term [avant-garde] is viewed as obsolete, even derogatory. This suggests we are in the presence of a major symptom."

Outside of artistic and literary history, the term "avant-garde" has fared still worse since the early 1970s. As the critic Evan Mauro notes, "in social and political writing since at least the Situationists in France, its fraternal twin 'vanguardism' has become a leftist code word for an outdated strategy, no longer the necessary ideological and intellectual preparation for social transformation, but rather an anti-democratic elitism and crypto-totalitarianism." In part, Mauro argues, this reflects a pervasive cultural malaise: "today any putatively transgressive artistic practice falls flat against, in no particular order, intellectual relativism, a culture of permissiveness, and state-supported, market-segmented cultural difference - the avant-garde's ancient target of a stable bourgeois moral order long since displaced by the universal imperative to 'Enjoy!'" George Katsiaficas argues that "generally speaking, what is called 'avant-garde art' today is completely depoliticized.."

Some scholars and activists, however, continue to argue for the value of the term "avant-garde" to describe a truly culturally and socially transgressive value in some vanguard artistic activity, chief amongst them Hal Foster. Commenting upon Hal Foster's concept of the contemporary avant-garde, Rachel Wetzler writes that "for Foster, the artists who constitute the avant-garde of today are the ones who take the formlessness of the 'capitalist garbage bucket,' with its undifferentiated proliferation of images and texts, and give it coherent form, making the precarious conditions of contemporary life tangible in a way that might point toward a different future."

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI