Summary of Kazimir Malevich

Kazimir Malevich was the founder of the artistic and philosophical school of Suprematism, and his ideas about forms and meaning in art would eventually constitute the theoretical underpinnings of non-objective, or abstract, art. Malevich worked in a variety of styles, but his most important and famous works concentrated on the exploration of pure geometric forms (squares, triangles, and circles) and their relationships to each other and within the pictorial space. Because of his contacts in the West, Malevich was able to transmit his ideas about painting to his fellow artists in Europe and the United States, thus profoundly influencing the evolution of modern art.

Accomplishments

- Malevich worked in a variety of styles, but he is mostly known for his contribution to the formation of a true Russian avant-garde post-World War I through his own unique philosophy of perception and painting, which he termed Suprematism. He invented this term because, ultimately, he believed that art should transcend subject matter -- the truth of shape and color should reign 'supreme' over the image or narrative.

- More radical than the Cubists or Futurists, at the same time that his Suprematist compositions proclaimed that paintings were composed of flat, abstract areas of paint, they also served up powerful and multi-layered symbols and mystical feelings of time and space.

- Malevich was also a prolific writer. His treatises on the philosophy of art addressed a broad spectrum of theoretical problems conceiving of a comprehensive abstract art and its ability to lead us to our feelings and even to a new spirituality.

Important Art by Kazimir Malevich

The Reaper

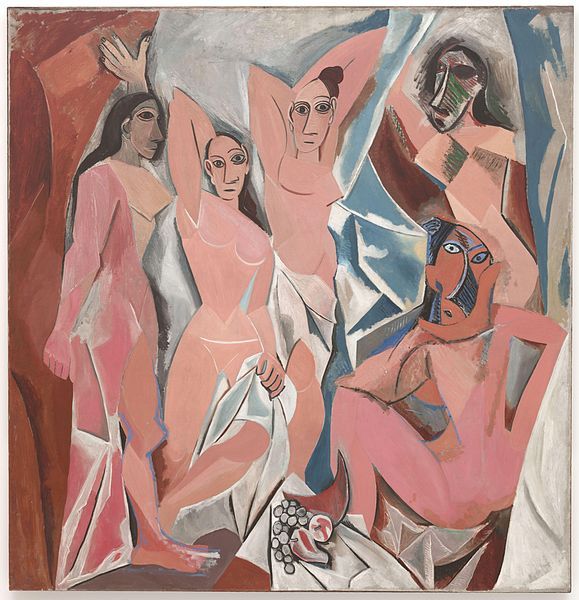

In The Reaper, Malevich explored the human figure through a pictorial vocabulary reminiscent of the work of the French Cubist Fernand Leger. The body and the dress of the peasant are rendered in conical and cylindrical forms adopted by Malevich from the Cubist school. The flat and vibrant palette of the painting derive from Post-Impressionism and later modernists, indicating Malevich's exposure to the dominating artistic styles of his time. The peasant theme, part of the more general modernist attraction to the "primitive" is reinterpreted from the traditional folk motif, known as Lubok, which was in vogue in popular prints and textile designs within the Russian avant-garde milieu. While still clearly figurative, this composition anticipates the move toward abstraction by the employment of abbreviated and stylized forms.

Oil on canvas - The Fine Arts Museum, Nizhnij Novgorod, Russia

Woman With Pails: Dynamic Arrangement

In this composition, also derived from Fernand Leger (through Paul Cézanne, who believed that all forms in nature could be reduced to the sphere, cylinder, and cone), Malevich moved more decisively toward abstraction by dissecting the figure and picture plane into a variety of interlocking geometric shapes. The figure is still identifiable, as are the pails that she carries; Malevich has not yet abandoned representation entirely. The general palette is comprised of cool colors dominated by blues and grays, though the accents of red, yellow, and ochre add to the visual dynamic of the composition, thus bringing us closer to the feeling that Malevich intended to communicate as indicated by the title. The few identifiably figurative elements, such as the figure's hand, seem to be lost inside the whirlpool of completely abstracted forms that structure the canvas.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

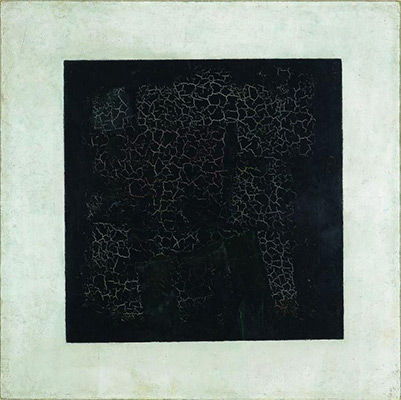

Black Square

Now badly cracked, the iconic Black Square was shown by Malevich in the 0.10 exhibition in Petrograd in 1915. This piece epitomized the theoretical principles of Suprematism developed by Malevich in his 1915 essay From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Realism in Painting. Although earlier Malevich had been influenced by Cubism, he believed that the Cubists had not taken abstraction far enough. Thus, here the purely abstract shape of the black square (painted before the white background) is the single pictorial element in the composition. Even though the painting seems simple, there are such subtleties as brushstrokes, fingerprints, and colors visible underneath the cracked black layer of paint. If nothing else, one can distinguish the visual weight of the black square, the sense of an "image" against a background, and the tension around the edges of the square. But according to Malevich, the perception of such forms should always be free of logic and reason, for the absolute truth can only be realized through pure feeling. For the artist, the square represented feelings, and the white, nothingness. Additionally, Malevich saw the black square as a kind of godlike presence, an icon - or even the godlike quality in himself. In fact, Black Square was to become the new holy image for non-representational art. Even at the exhibition it was hung in the corner where an Orthodox icon would traditionally be placed in the Russian home.

Oil on canvas - Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Airplane Flying

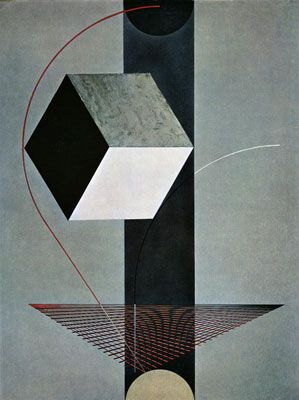

As early as 1914, Malevich had become interested in the possibilities of flight (as had the Futurists) and the idea that the airplane might be a symbol for the awakening of the soul surrounded by the freedom of the infinite. Malevich was also interested in aerial photographs of landscapes, although he later backed away from this source of inspiration, feeling that it led him too far from his vision of a totally abstract art. However, at the time, in Airplane Flying Malevich was able to further explore the pictorial potential of pure abstraction. The rectangular and cubic shapes are arranged in a solid, architectonic composition. The yellow contrasts starkly with the black, while the red and blue lines add dynamic visual accents to the canvas. The whiteness of the background remains unobtrusive but contrasting, and has infused the interplay of colorful shapes with its energy. Malevich believed that emotional engagement was required from the viewer in order to appreciate the composition, which constituted one of the key principles of his theory of Suprematism. Indeed, Malevich wrote about expressing the feeling of the "sensation of flight, metallic sounds..." and other technological advances of the modern age. His abstract painting was meant to convey the concept (abstract idea) of the plane flying in space.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

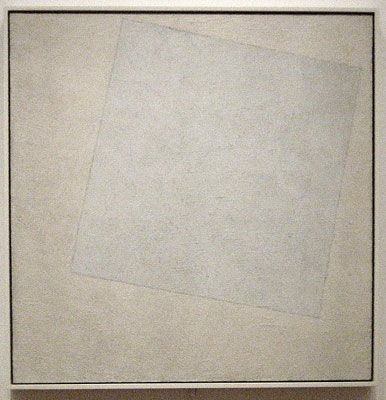

White on White

Malevich repeatedly referred to "the white" as a representation of the transcendent state reached through Suprematism. White was the artist's symbol for the concept of the infinite as the white square dissolves its material being into the slightly warmer white of the infinite surrounding. This painting can be seen as the final, complete stage of his "transformation in the zero of form," since form has almost literally been reduced to nothing. The pure white of the canvas has negated any sense of traditional perspective, leaving the viewer to contemplate its "infinite" space. The slight change in tonality, however, distinguishes the abstract shape from the background of the canvas, and encourages close viewing The picture is thus bled of color, the pure white making it easier to recognize the signs of the artist's work in the rich paint texture of the white square, texture being one of the basic qualities of painting as the Suprematists saw it. Painted some time after the Russian Revolution of 1917, one might read the work as an expression of Malevich's hopes for the creation of a new world under Communism, a world that might lead to spiritual, as well as material, freedom.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

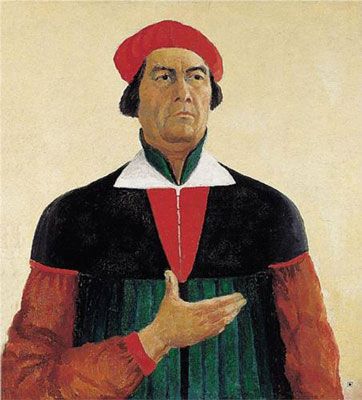

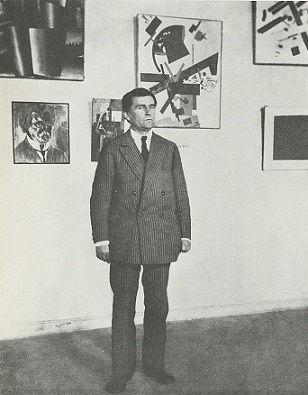

Self-Portrait

In the late years of his life, Malevich returned to exploring the more conservative themes of his earlier work such as peasants and portraits. In fact, Malevich was forced to abandon his modernist style under Joseph Stalin in the 1930s. The artist's Suprematist goal of achieving a "blissful sense of liberating non-objectivity" did not square with the prescribed Social Realist style that was being dictated at the time. In the work pictured here, Malevich paints himself as a Renaissance artist, seriously posed in red and black against a neutral background, his gesture a reflection of that of the artist Albrecht Dürer in his renowned Self-Portrait (1500). Here, the unity of the mind and the hand of the artist, highlighted on the central axis, bears a slightly different meaning: his hand is open and willing, but suspended, as his mind broods over the closing down of artistic freedom under Stalin's rule. And yet, the artist has "signed" the painting with his own black square in the lower right corner.

Oil on canvas - Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Biography of Kazimir Malevich

Childhood and Education

Malevich was born in Ukraine to parents of Polish origin, who moved continuously within the Russian Empire in search of work. His father took jobs in a sugar factory and in railway construction, where young Kazimir was also employed in his early teenage years. Without any particular encouragement from his family, Malevich started to draw around the age of 12. With his mind set firmly on an artistic career, Malevich attended a number of art schools in his youth, starting at the Kyiv School of Art in 1895.

In 1904, Malevich moved to Moscow to attend the Stroganov School of Art. He also took private classes from Ivan Rerberg, an eminent art instructor. Malevich continued his training in the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, where such artists as Leonid Pasternak and Konstantin Korovin taught him Impressionist and Post-Impressionist techniques of painting. Malevich's early work was largely executed in a Post-Impressionist mode; however the influence of Symbolism and Art Nouveau on his early development was just as significant.

Mature Period

A shift toward decidedly more avant-garde aesthetics occurred in Malevich's work around 1907, when he became acquainted with such artists as Wassily Kandinsky, David Burliuk, and Mikhail Larionov. In 1910, Larionov invited Malevich to join his exhibition collective named the Jack of Diamonds. Malevich also held memberships in the artistic groups Donkey's Tail and Target, which focused their attention on Primitivist, Cubist, and Futurist philosophies of art. After quarreling with Larionov, Malevich took on a leading role in the association of the Futurist artists known as the Youth Union (Soyuz Molodezhi) based in Saint Petersburg,

Most of the Malevich's works from this period concentrated on scenes of provincial peasant life. From 1912 to 1913, Malevich mostly worked in a Cubo-Futurist style, combining the essential elements of Synthetic Cubism and Italian Futurism, resulting in a dynamic geometric deconstruction of figures in space. In 1913, Malevich took part in one of the most significant artistic collaborations of modern times, creating set designs for the opera Victory over the Sun. In 1915, Malevich laid down the foundations of Suprematism when he published his manifesto, From Cubism to Suprematism, abandoning figurative elements in his painting altogether and turning to pure abstraction.

The October Revolution of 1917 opened a new chapter for Malevich. In 1918, he joined the People's Commissariat for Enlightenment as an employee of its Fine Arts Department, known as IZO. The new agency was to administer museums and to oversee art education in the new Soviet Republic. Malevich also taught at the Free Art Studios (SVOMAS) in Moscow, instructing his students to abandon the bourgeois aesthetics of representation and to venture instead into the world of radical abstraction. That same year, Malevich designed the decorations for a performance of Vladimir Mayakovsky's Misteriya-Buffa, which marked the first anniversary celebration of the Communist Revolution.

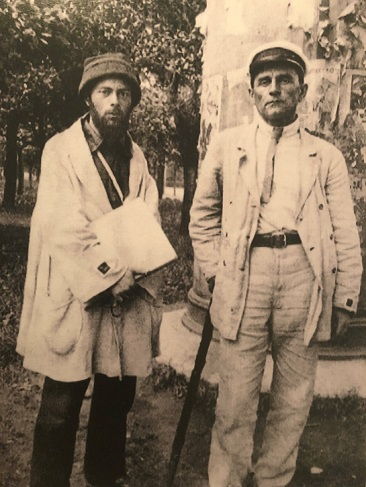

In 1919, Malevich completed the manuscript of his new book O Novykh Sistemakh v Iskusstve (On New Systems in Art) in which he attempted to apply the theoretical principles of Suprematism to the new state order, encouraging the deployment of avant-garde art in service to the state and its people. Later that year, however, Malevich left the capital for the town of Vitebsk, where he was invited to join the faculty of the local art school directed by Marc Chagall, and also El Lissitzky was on the faculty and ran the printing press.

When Chagall left Vitebsk for Paris (or was effectively pushed out by the charismatic Malevich that developed a strong following), Malevich remained as the influential leader of the Vitebsk school. There he organized students into a group under the name of UNOVIS, an abbreviation, which could be translated as Affirmers of New Art. Quite particularly, the group was a collective where no individual signed a work with their own name, only with the name of the group. No longer focused on painting proper, the UNOVIS group, especially after its move to Petrograd in 1922, designed propagandistic posters, textile patterns, china, signposts and street decorations, reminiscent of the activities undertaken at the Bauhaus School in the German Weimar Republic.

Malevich continued to develop his Suprematist ideas in a series of architectural models of utopian towns called Architectona. These maquettes were composed of rectangular and cubic shapes arranged to enhance their formal qualities and aesthetic potential. Malevich was allowed to take these models to exhibitions in Poland and Germany, where they sparked critical interest from local artists and intellectuals. Malevich left several Architectona models, as well as theoretical texts, paintings, and drawings in Germany after his hasty departure for Russia. In Soviet Russia, however, a different cultural paradigm was set in motion. The artistic flourish of the 1920s was curtailed by the advent of state-sponsored Socialist Realist art, which eventually came to suppress all other artistic styles.

Late Years and Death

Malevich and his work were doomed to descend into obscurity in such belligerently conservative socio-cultural circumstances. In 1930, Malevich was arrested and questioned about his political ideologies upon his return from a trip to the West. As a precautionary measure, the artist's friends burned some of his writings. In 1932, a major state-endorsed exhibition commemorating the 15th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution was held in Moscow and Leningrad (formerly Petrograd, and Saint Petersburg before that). Malevich was included, only now his paintings were accompanied by pejorative slogans, labeled as essentially "degenerate" and anti-Soviet. Barred from state schools and exhibition venues, in his late years the artist returned to old motifs of peasant and genre scenes, while also executing a number of portraits of friends and family. He died of cancer in Leningrad in 1935 and was buried in a coffin of his own design, with the image of the Black Square placed appropriately on its lid. Having previously been consigned to the basements of Soviet museums, it was only under Gorbachev in 1988 that Malevich's works were brought out and shown to the public. Before glastnost, there were only a few of Malevich's works available for viewing in America -- the ones available were the results of the extraordinary measures taken by New York's Museum of Modern Art's Alfred Barr, who smuggled 17 of Malevich's paintings - some of which were rolled up in his umbrella - out of Nazi Germany in 1935.

The Legacy of Kazimir Malevich

Malevich conceived of Suprematism prior to the 1917 Revolution, but its influence was already significant amongst the Russian avant-garde. Malevich's use of non-representational imagery and his interest in dynamic geometrical form in pictorial space influenced the art of Lyubov Popova, Alexander Rodchenko, and El Lissitzky. In 1922, the artist devised his three-dimensional Suprematist works, called arkhitektony, which were studies in architectural form. In Soviet Russia Socialist Realism become the only accepted style and in the country Malevich (and his abstraction ideas) was relegated to obscurity.

Fortunately, some of Malevich's ideas were exported to the West through the exhibition of these Suprematist models for Utopian towns in Poland and Germany, where the avant-garde discourse would incorporate Malevich's theoretical perspectives on abstraction. Malevich made only one trip to the West in 1927, accompanied by a number of Suprematist canvases, which were exhibited at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, where they were subsequently seen by many European artists. In Warsaw, Malevich met with artists who had studied with him in Vitebsk, and whose work was heavily influenced by Malevich's monochrome works.

More broadly, Malevich's influence is evident in the work of later artists in Europe and particularly the United States whose work consists of totally abstract shapes that represent technology, universality, or spirituality - all ideas stemming from Malevich. New York's Museum of Modern Art first director Alfred Barr purchased a large collection of his works. Via these routes, Malevich paved the way for many generations of later abstract artists - especially Ad Reinhardt and the Minimalists - to free themselves from reliance upon the real world.

Influences and Connections

Useful Resources on Kazimir Malevich

- Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism (2003)Our PickBy Nina Gurianova, Jean-Claude Marcade, Tatyana Mikhienko, Yevgenia Petrova, Vasilii Rakitin, Kazimir Malevich, Matthew Drutt

- Kazimir Malevich and the Art of GeometryBy John Milner

- Kazimir Malevich, 1878-1935By John E. Bowlt

- Kazimir Malevich: The Climax of DisclosureBy Rainer Crone, David Moos

- Kazimir Malevich in the State Russian MuseumBy Yevgenia Petrova