Summary of Socialist Realism

Socialist Realism generally refers to the formally realistic, thematically artificial style of painting which emerged in Russia in the years following the Communist Revolution of 1917, particularly after the ascent to power of Josef Stalin in 1924. The term also encompasses much of the visual art produced in other communist nations from that period on, as well as associated movements in sculpture, literature, theater, and music. Russia had a proud history of realist painting as social critique, notably through the work of Peredvizhniki artists such as Ilya Repin, and had also been at the forefront of developments in avant-garde art during the early 1900s. But as the realities of socialist rule began to bite in the USSR, artists were increasingly compelled - often on pain of imprisonment or death - to present positive, propagandist images of political leaders, cultural icons, and everyday conditions in the new Soviet republic. Initially incorporating artists of talent and daring such as Isaak Brodsky and Yuri Pimenov, by the 1940s Socialist Realism was a stifling paradigm in which all political critique and obvious formal experiment was snuffed out. Nonetheless, it continued to channel the activities of technically gifted artists, writers, and even composers - Sergei Prokofiev's 1939 cantata Zdravitsa, composed for Stalin's 60th birthday, is still widely recognized as a significant work, in spite of its brazenly propagandist libretto, and unsavory political subtexts. This is one of many fascinating examples of what happens when a totalitarian regime attempts to extend its control over every avenue of cultural expression.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- There is an important distinction to be made between Socialist Realism and Social Realism; though to some extent, the former grew out of the latter. The stylistic heritage of Socialist Realism was in the tradition of Realist painting which, in Europe and in Russia during the late nineteenth century, had pushed back against the pompous Neoclassical history painting populating state-sanctioned galleries. From Gustave Courbet in France to Russia's own revolutionary Peredvizhniki group, Realism had been a force not just for political critique, but also for celebrating nature and the common lot of humanity. Socialist Realism in Russia and elsewhere maintained the naturalistic style and (superficially at least) the egalitarian impetus of this older movement. But it generally existed in cultures where truthful visual reportage had become impossible. As a result, it maintained the veneer of Realism while generally abandoning its underlying vision.

- Boris Iagonson, a popular artist of Stalin's era, stated that the success of Socialist Realist painting lay not in any stylistic innovation, but in the "staging of the picture". Socialist Realist paintings often have something of the quality of film-stills, as various actors, playing assigned roles in choreographed scenes, are presented in a highly accurate style, as archetypes of the type of citizen that would populate the successful Socialist state. Well-fed and tireless peasants, fearless leaders, visionary scientists, legendary explorers, and various other exemplars of the Socialist cause, litter the canvases produced in Russia and across the non-democratic part of the Socialist world between the 1920s and 1950s.

- Like every art movement in history, Socialist Realism supported artists of technical skill and vision (indeed, it is worth acknowledging that only in relatively recent history, and only in certain parts of the world, has art achieved a position of freedom from political propaganda). Isaak Brodsky is one of the many prodigiously talented painters who plied their trade in a style which imposed thematic and formal limits on it. By the 1940s and 1950s, a younger generation of artists, most of whom were born into Soviet rule, were producing a more staid body of images. However, some continued to innovate by whatever means were open to them, turning to effects of lighting, for example, or Impressionist technique, as ways of imposing a stamp of individuality on their work.

Artworks and Artists of Socialist Realism

Increase the Productivity of Labor

In this work - whose title is also translated as "Give Us the Heavy Industry" - we see five men toiling in a steel factory. The work is hard; they are wearing leather to protect themselves as they struggle bare-chested towards a vast flame. The glare from the fire occupies a large corner of the canvas, but the men are clearly the subject of the work. Their profiles show stoical expressions; they are unflinching in the blistering heat. In the background, other men push coal towards enormous furnaces, while an open door revealing a cityscape beyond reminds us of the people who will benefit from their labor. Stylistically, the piece is a striking blend of Socialist Realist motifs and Pimenov's early avant-garde influences, typical of the early period of the movement.

Born in 1903, Pimenov was too young to be involved in the avant-garde activities of the 1910s, but his workers' exaggerated, elongated, and sinuous forms express his youthful debt to German Expressionism, while the almost collage-like appearance generated by bold, distinct blocks of color is loosely reminiscent of Constructivist photo-montage. At the same time, the work encapsulates many of the thematic norms of Socialist Realism: its nominal subject is the industrial might of the new Soviet state, but its real theme is the glory of collective human labor dedicated to that cause. Unified by their physical strength, the men's collaborative endeavor is also symbolized by their shared postures as they lean in towards the heat, one of them rendered in glowing gold like a hero of classical statuary. The blackened faces of the men at the front of the group take on an almost cyborg-like quality, metaphorically merging with the spirit of industry as they become embodiments of the "New Soviet Man". At the same time, this machine aesthetic is itself redolent of the avant-garde spirit of Cubo-Futurism, soon to be crushed under the heel of state-sponsored Socialist Realism.

In its striking blend of propagandist motifs and stylistic invention, Pimenov's work is an interesting example of early Socialist Realism, and indicates the limited creative freedom which artists continued to be afforded.

Oil on canvas - Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

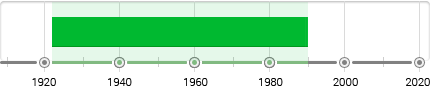

Lenin in Smolny

Brodsky's portrait of Lenin, one of the most iconic works of Socialist Realist art, depicts Lenin at the Smolny Institute, the headquarters of the revolutionary government in the months immediately following the October Revolution. All the details of the scene are intended to contrast with the excessive opulence of Tsarist Russia, from the dustsheets thrown over the chairs in the makeshift office to Lenin's humble attire and expression of calm concentration. Standing at nearly three meters high, the canvas presents the leader as almost life-size, enhancing the quality of naturalistic accuracy which pervades the work. The rendering of the polished wood of the furniture, the texture of the fabrics, and the gleaming floor, show Brodsky's technical talent - the piece is almost photographic in its accuracy.

Born in 1884 in modern-day Ukraine, Isaak Brodsky was one of the most talented Russian artists of his generation, and had been tutored in his youth by Ilya Repin, figurehead of the Peredvizhniki group, who was responsible for iconic works such as Barge-Haulers on the Volga (1870-73). Though he was of an age to participate in the revolutionary aesthetic experiments of the 1900s-10s, Brodksy's political commitments found expression through an accurate but emotive painting style influenced by late-nineteenth-century Russian Realism and European Naturalism. Indeed, he was arguably the last great artist of the Peredvizhniki era; in its close attention to informal physical posture, this work stands in the great tradition of Russian Realist portraiture inaugurated in the previous century by artists such as Ivan Kramskoi.

Lenin in Smolny was one of a number of works which Brodksy produced after Lenin's death in 1924 to canonize the leader. Like many works of Socialist Realism, it looks back to a halcyon period or event in the early history of the Soviet Union - in this case the first few months of revolutionary government - rather than engaging with the complexities of contemporary reality. Nonetheless, it gives a sense of the fervor and optimism of those early days, and of the faith that was placed in Lenin's leadership, while at the same time predicting the less accomplished version of Brodksy's Realist style that would be imposed from above after 1932.

Oil on canvas - Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

New Moscow

Yuri Pimenov's 1937 painting places the viewer in the back of an open-top car cruising through central Moscow, a female driver at the wheel. All around is progress: cars are everywhere, a tram moves towards new high-rise buildings, while an entrance to the new and much vaunted Moscow subway is visible to the side. Scattered across the scene like flecks of color, busy people hurry about their day. Layers of symbolic imagery can be detected beneath the everyday surface of the image; the red flower propped on the windshield of the car, for example, indicates the artist's support for the Soviet Government.

In spite of the strict enforcement of Socialist Realist principles by this point in Stalin's regime, Pimenov's work indicates the limited but inevitable extent to which stylistic experiment continued to be practiced by Russian artists. The painting is broadly Impressionist in style, as if recreating the feel of rainswept streets; but the hazy quality also evokes a sense of dreamy aspiration (just as the female driver nods to social and cultural progress under the new regime).

At the same time, as with much Socialist Realist art of the 1930s, it is impossible not to see this image as expressing a grim dramatic irony. The previous year, the so-called "Moscow Trials", in which swaths of government officials and members were tried as saboteurs on spurious grounds, had commenced in courtrooms across the capital. This brought forth the era known as the "Great Terror", which saw unprecedented levels of police surveillance and extra-judicial killings. Artists and writers feared for their lives in this climate, and the "New Moscow" in which Pimenov was working was very different from the one he was compelled to represent; and open-top motor cars (or any car for that matter) were a luxury unimaginable for the majority of the country's population.

Oil on Canvas - Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

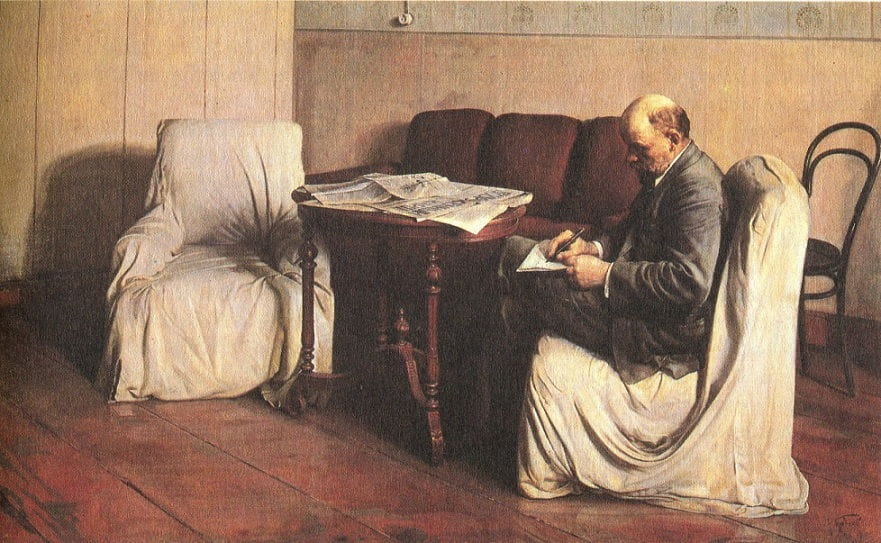

Stalin and Voroshilov in the Kremlin

Standing at nearly three meters tall, Aleksandr Gerasimov's monumental double-portrait shows Joseph Stalin accompanied by his faithful ally Kliment Voroshilov, one of the original five Marshals of the Soviet Union (the state's highest military rank), a prominent figure in Stalin's government and frequent subject of Gerasimov's paintings. Indeed, Nikita Khrushchev would later remark that Voroshilov spent more time in Gerasimov's studio than attending to his political duties. In this painting, however, he, like Stalin, seems a model of concentrated attention. The pair mimic each other's postures in a show of unity as they walk alongside a Kremlin tower. The men appear deep in conversation, their forward glances signifying a focus on the Soviet Union's bright future. In the background, barely visible, the proletariat form a line outside a factory.

Unlike other Socialist Realist artists who came of age in the pre-revolutionary era, Aleksandr Gerasimov never had an experimental phase. During the 1900s-10s, he had championed realistic draftsmanship over the formal extravagance of the Russian avant-garde, and by the late 1920s found the tide of official opinion turning decisively in his favor. Specializing in adulatory portraits of the Soviet leadership, Gerasimov rose to become head of the USSR's Union of Artists (set up in 1932 to replace all independent artists' groups) and the Soviet Academy of Arts. Derided as a government stooge by some, his work nonetheless shows a formidable technical skill, and a light-touch engagement with Impressionist technique.

This particular work is rich in symbolism. The theme of hope is enhanced by a sky turning blue in the background, as the clouds part after a rainstorm, revealing a spring day. The dark colors of the men's clothes match those of the railings and architecture of post-revolution Moscow, while solitary flashes of red on Voroshilov's military uniform echo the brightness of the Soviet Star atop the Kremlin, and of the Communist flags flying in the background. In such works, we can truly see the cult of personality emerging, a lynchpin of Socialist Realist style. Stalin is presented as a brave, bold and inspiring leader, beloved father of his mass of Soviet children.

Oil on canvas - Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Bread

This work, also known as "Grain", depicts a lively scene of activity on a collective farm or Kolkhoz. A group of women smile and talk as they work the harvest, holding shovels, tying bags, and carrying grain; a central figure rolls up her sleeves, standing tall and proud with a beaming smile on her face. Dominating the composition is a large pile of grain waiting to be transported, whose presence adds to a warm color-palette suggesting optimism, dynamism, and vitality.

Born in February 1917, the Ukrainian artist Tatiana Yablonskaya was just a few months old when the Bolshevik Revolution transformed her home-country. Unlike other Socialist Realist artists, therefore, she had never known life outside the Communist regime. Nonetheless, her work often reflects an aesthetic and cultural commitment to her home region, historically known as "Russia's breadbasket" because of the rich soil and temperate climate of the Ukraine. Although this piece is a work of Realism, like many paintings which bear that title it was in fact the product of hundreds of sketches and studies. The artist wanted to make an epic image full of movement, sound and sunlight, stating: "I did my best to express the feeling that overwhelmed me when I was at the collective farm. I strove to express the joyous communal labor of our beautiful people, the wealth and power of our collective farms, and the triumph of Lenin's and Stalin's ideas in the socialist reconstruction of the village."

However far this statement was from the horrendous reality of life on many Soviet collective farms, there is an undeniable naturalistic vigor to this work which connects it to the Russian Realist genre painting of the late nineteenth century. Yablonskaya was a garlanded figure in Stalin's Russia, awarded a swath of state prizes, and even becoming a member of parliament in her native Ukraine during the 1950s.

Oil on canvas - Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Letter from the Front

In this image we see a mother and her young children gathered in an open doorway, reading a letter from a father or brother at the front, brought home by a fellow soldier sent presumably on recovery leave. The happy group smile alongside the injured friend in uniform, the cheerful optimism of the scene complemented by the bright colors of the sky and the sunlight which drenches the village square, bathing the children's faces in light. The piece pulsates with warmth, suggesting little of the anxiety and trauma which would presumably have accompanied such a meeting.

Alexander Laktionov was perhaps the quintessential mid-century Russian Socialist Realist. Tutored in a bright, sharp, photo-realistic style informed by the Dutch Masters, he produced unflinchingly, at times absurdly, optimistic images of life in Soviet Russia, as well as portraits of key bureaucrats, and cultural icons such as cosmonauts. Painted two years after the end of the Second World War, Letter from the Front perhaps provided the kind of palliative gloss over recent traumatic events which the Russian public were craving, and it quickly became a popular classic, winning the Stalin Prize for art (although the Committee for Artistic Affairs was reportedly troubled by the awful condition of the porch floor, and of the clothing worn by the mother).

Laktionov once declared that "to work without too much cleverness, without fuss, constantly learning from nature, drinking in the true source of eternal freshness and understanding life - that is true happiness". Given contemporary knowledge of the horrors of the Eastern Front, it is hard to imagine how any artist could depict this subject-matter in such a manner, but Laktionov's popularity with the Russian public, and not just with the powerful circles in which he moved, suggests an enduring public appetite for art "without too much cleverness."

Oil on canvas - Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The Founding Ceremony of the Nation

After the Second World War, communist rule spread to several countries in eastern Europe - a group of satellite states which became known as the Eastern Bloc - while revolutions in Asia, including in North Korea and China, brought the culture of Soviet Socialist Realism to Russia's Eastern neighbors. In this picture celebrating the conclusion of the Chinese Civil War of 1945-49, we see many of its tenets replicated. Chairman Mao addresses his people in Tiananmen Square during the inaugural ceremony of the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949. Behind him stand a group of officials looking on while the warm reds and golds of the Chinese lanterns hang heavy with national and political symbolism. These contrast sharply with the blue sky, in which doves fly, signaling a bright and peaceful future (the day had in fact been gloomy and overcast). Lanterns are presented as symbols of prosperity, while chrysanthemums represent longevity. It is painted in a folk-art style, using bright contrasting colors that would appeal to a Chinese aesthetic.

Following the communist revolution, the State quickly extended control over artistic culture much as Stalin had done in Russia, in order that their achievements could be immortalized on canvas for the viewing public. This piece was commissioned by Chairman Mao himself, and interestingly saw a number of revisions to the central subjects in its lifetime, as political leaders fell from power in the two decades after its release. The artist also altered the height of the Chairman at various points, adding an extra inch during the original composition, and making the leader taller with each new revision. The painting was reproduced more than a million times after its completion.

Dong Xiwen himself had been born in 1914 in eastern China, and had been a sympathizer of the Communist cause before the Revolution, as well as an artist, copyist, and civil engineering student at various institutions in China and Vietnam. He was celebrated for his works combining a nineteenth-century Western Realist aesthetic with a decorative sensibility reflecting his national heritage, perhaps arising from his time producing replicas of wall-paintings as a researcher at the Dunhuang Art Research Institute during the 1940s. This painting remains his best-known work, and a hugely iconic image in China.

Oil on canvas - National Museum of China, Beijing

Beginnings of Socialist Realism

It is an irony of cultural history that one of the most proscriptive movements in twentieth-century art emerged from one of the most subversive and dynamic artistic cultures to be found anywhere in the world a few years previously. At the turn of the century, Russian art had stormed onto the international scene. Avant-garde experiment accompanied a climate of political agitation, peaking in the years preceding and following the Russian Revolution of 1917, when movements such as Rayonism and Cubo-Futurism, Neo-Primitivism, Russian Futurism, Suprematism, and Constructivism were conceived. Painters, designers, architects, and sculptors such as El Lissitzky, Kazemir Malevich, and Alexander Rodchenko redefined millennia of artistic tradition, producing some of the most formally subversive early-modern art anywhere in the world. Within the literary sphere, poets such as Vladimir Mayakovsky were making similar leaps forward. This wave of activity often had a distinctly nationalist animus: in 1912, the Russian Primitivist painter Natalia Goncharova declared that "[c]ontemporary Russian art has reached such heights that, at the present time, it plays a major role in world art. Contemporary Western ideas can be of no further use to us."

For a time, the avant-garde was tolerated and even encouraged by the new communist government: the Russian artist Naum Gabo, who emigrated to Germany in 1922, recalled that "at the beginning we were all working for the Government." To some extent, this freedom reflected the lack of attention which the Central Committee - the USSR's new ruling body - was paying to cultural matters while it was struggling with the Russian Civil War of 1917-22. As early as 1922 - the year that the war ended, and that Joseph Stalin began to consolidate his control over the USSR - the State was already beginning to clamp down on freedom of creative expression; when Stalin rose to full power upon Lenin's death in 1924, a more drastic shift in culture followed. Unlike most movements in art history, which tended to grow organically out of a socio-historical moment, Socialist Realism was imposed from above through informal pressure from the early 1920s onwards, and as state policy from 1934.

Lenin had already set the wheels in motion for this change when, following the Revolution of 1917, he laid out a new socially engaged agenda for the arts: "[a]rt belongs to the people. It must leave its deepest roots in the very thick of the working masses. It should be understood by those masses and loved by them. It must unite the feelings, thoughts and the will of the masses and raise them. It should awaken in them artists and develop them." This statement epitomized a proclivity for Realism that was nonetheless loose enough for artists such as Gabo and Antoine Pevsner, for example, to define the tenets of Russian Constructivism - a form of geometric abstraction far from any conventional notion of Realism - within a statement entitled "The Realistic Manifesto" (1920). And Realism itself, in the work of the Peredvizhniki painters and authors such as Chekhov and Tolstoy, had its own history of cultural radicalism within Russia.

But Stalin had far more specific and proscriptive ideas about how art should serve the new Soviet State. In an ironic manipulation of Constructivist theory, he asserted that art should serve a functional purpose: however, for Stalin, this simply meant that it should offer unambiguously positive images of life in communist Russia, in a 'true-to-life' visual style which could be easily appreciated by the masses. Stalin described artists as "engineers of the soul", declaring that art should be "national in form, socialist in content". Put simply, art was to be used as propaganda.

Socialist Realism was to be starkly differentiated from the work of the European avant-gardes which, up until Lenin's death, had remained broadly in line with fashionable thought in Russian artistic culture. Stalin despised the avant-garde as elitist and inaccessible, and many of its chief proponents fled to Europe; if they stayed, they were isolated, banished, imprisoned, or even executed, as they later would be in Nazi Germany. Keen to distance his cultural policies from those which had survived in some form under Lenin, Stalin decommissioned art schools that taught avant-garde theories, and Russia's formidable public and private collections of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painting were removed from walls, rolled up, and transported like political prisoners to Siberia.

The Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia (AKhRR)

One of the most important organs of Socialist Realism was the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia (AKhRR). Founded in 1922, the group had branches in Moscow and Leningrad, and to some extent took up the mantle of The Society for Itinerant Art Exhibitions, which since 1870 had existed to promote the work of the Peredvizhniki. The Peredvizhniki ("Itinerants" or "Wanderers") were an evolving group of Russian Realist painters who, since the 1860s, had sought to depict the realities of life in late Imperial Russia, and to capture the beauty of the Russian landscape. Significantly, the first leader of the AKhRR was Pavel Radimov, who was also the last chairman of the Peredvizhniki group, which folded in 1923. The artists who founded AKhRR alongside Radimov, such as Sergey Malyutin, were established and talented painters in the Realist tradition, and were shortly joined by other artists associated with the late Peredvizhniki era, such as Abram Arkhipov, as well as younger painters, most notably Isaak Brodsky.

The AKhRR produced paintings depicting the everyday life of the working people of post-Revolutionary Russia; just as Russian and European artists of the Naturalist and Realist schools had composed genre paintings depicting the lives of the working poor from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. The group were inspired by the lives of the Red Army, urban workers, rural peasants, revolutionary activists, and labor heroes: good Soviet role models, to whom the masses could relate. The tension in the group's approach, however, arose from the fact that they were now nominally living in the kind of promised era of equality towards which earlier movements had directed their critical energy, and they came under increasing pressure from political forces to maintain the façade that such equality had been achieved. The traditional remit of Naturalism and Realism - to paint with unflinching truthfulness - was thus inevitably compromised. Nonetheless, the group contained undeniable talents such as Brodsky, and was influential, and to some extent, creatively fertile over its short existence. In 1932, it was abolished, like all non-state-sanctioned artists' groups.

The Society of Easel-Painters (OST)

The Society of Easel-Painters (OST) was formed in Moscow in 1925, by painters including Yuri Pimenov and Aleksander Deyneka. It emerged out of the passionate debates raging in the city at that time over the purpose and value of art; its manifesto stated: "[a]t the age of [the] building of Socialism, active artistic forces must be a part of this building and one of the factors of cultural revolution in the areas of reformation and design of the new life, and the creation of new, socialist culture". The organization worked under a number of rules, including that the artist must strive to achieve a complete painting, and must discard 'sketchiness'. The OST also renounced what was referred to as 'pseudo-Cezannism' - a reference to the French proto-Cubist painter Paul Cezanne, seen as the first artist to break up the picture frame into a series of planes - as the destroyer of harmonious form, line, and color. The group denounced Non-objectivism - a form of pure abstraction associated with the Suprematist artist Kazemir Malevich - as a manifestation of artistic irresponsibility, vagueness, and itinerancy.

The OST's return to easel painting was partly a way of setting its stall out against the Constructivist ethos which held that fine art should be merged with functional crafts such as engineering and architecture in order to fulfil its revolutionary potential. In its return to a more traditional view of the role of the painter, the OST laid some of the philosophical groundwork of Socialist Realism. However, like the AKhRR, it remained an independent group, and was subject like all independent movements to faction and disagreement. In 1928, the group split in two, when a number of painters more interested in formal abstraction broke away from the group around Pimenov and Deyneka. Then, in 1932 the OST was disbanded.

Maxim Gorky's Doctrine

Socialist Realism took its cue not only from the Realist painting of artists such as Ilya Repin, but also from the literary Realism that had flourished in pre-Revolutionary Russia epitomized by the work of authors such as Leo Tolstoy, Anton Chekhov, and, in later years, Maxim Gorky. All three authors had produced subversive literary works portraying the iniquities of feudal life, with a truth to emotional, visual, and sensory experience that was breathtaking. Socialist Realism took much from the stylistic of literary Realism, with the qualification that it had to avoid relaying a whole swath of truths about the society it portrayed.

The literary basis of Socialist Realism is evident from a speech given in 1934 by Maxim Gorky, a Bolshevik-sympathizing Realist writer who had been exiled from the USSR by Lenin in 1921, for his criticism of the new regime. Returning in the 1930s on Stalin's personal invitation, just before his death, Gorky is seen by some to have abandoned his Realist principles in the propagandist works he produced for the state in the final years of his life. Addressing the Soviet Writers' Congress of 1934, Gorky sounded a clarion call for Socialist Realism, asserting that art had traditionally been the realm of bourgeoise indulgence, predicated on the economic oppression of the proletariat. "When the history of culture will have been written by the Marxists", he declared, "we shall see that the role of the bourgeoisie in the process of cultural creation has been greatly exaggerated, especially in literature, and still more so in painting, where the bourgeoisie has always been the employer, and, consequently, the law-giver." Socialist Realist art must follow four rules, Gorky went on: it must be proletarian: that is, relevant and coherent to the workers; it must be typical, in that it must represent the everyday lives of the Russian people; it must be stylistically Realist; and it must be partisan: it must actively support the aims of the Russian State and the Communist Party.

The Artists' Union of the USSR (1932) and the Congress of Soviet Writers (1934)

Before 1932, independent artists' groups were still nominally allowed to exist in the USSR, and there was no uniform policy on the enforcement of Socialist Realism, though artists and writers straying from endorsed styles certainly faced persecution. Early in 1932, the Central Committee announced that all existing literary and artistic groups would be disbanded, to be replaced by state-sanctioned Unions representing different artforms. This led to the founding of the Artists' Union of the USSR, effectively bringing the era of independent modern art in Russia - one that had been vitally active since the 1860s - to a close. The era of state-sanctioned Socialist Realism effectively began at this point, though it was only explicitly endorsed as Stalinist policy two years later at the Congress of Soviet Writers (1934). Andrei Zhdanov attended as the cultural spokesman of Stalin, and gave a speech rigorously endorsing the principles of Socialist Realism. From that point onwards, its tenets were actively enforced across all of the arts.

At the same time, Stalin was increasingly critical of the avant-garde pioneers of the previous three decades; painters who stayed in Russia such as Malevich were derided as "bourgeois", and found themselves increasingly isolated. Their work was removed from museums and gallery walls, and they were forced, at best, into obscurity or exile; at the same time, Realist artists and writers of the pre-Revolutionary era such as Repin were increasingly revered (an irony, given Repin's hostility to the authoritarian politics of his own era.) The Stalinist purges of the 1930s silenced most of the remaining opponents of Socialist Realism, including the art critic Nikolai Punin (an erstwhile champion of Malevich, who was charged with "anti-Soviet treachery" in 1949 and sent to the Vorkuta Gulag, near the Arctic Circle, where he died in 1953.)

Socialist Realism in the Public Sphere: Sculpture, Graphics, and Cinema

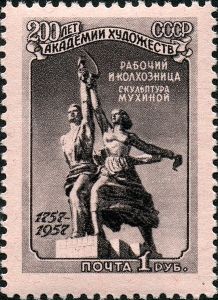

As it became a state-sanctioned aesthetic, Socialist Realism moved inexorably into the public space. Many pre-revolutionary sculptures and statues, seen to have been "erected in honor of the kings and their servants and not having interest from either historical or artistic hand", were removed under Lenin, so urban spaces became blank canvases, across which monumental propaganda battles could be waged. Statues depicting the new categories of Soviet citizen - from workers and scientists to school children - sprang up all over Russia. Socialist Realism in sculpture, in spite of the limits placed on its formal and thematic scope, was taken up by a number of talented artists, just as Socialist Realist painting had been. Amongst these was Vera Mukhina, whose Worker and Kolkhoz Woman (1937) was designed for the 1937 World Fair in Paris, before being moved to a prominent spot outside an exhibition center in Moscow. The sculpture presents an optimistic image of the "Kolkhoz" collective farming system, implemented during Stalin's first Five-Year Plan (1928-32), which in fact caused widespread famine (not to mention a drop in productivity).

At the same time, reams of posters were produced, often by unknown artists, depicting the proletariat worker busy in industry, and were pasted in town squares across the Republic. Socialist Realist photography also emerged as an active movement in the context of such public propaganda campaigns. It often depicted the beaming faces of liberated workers, captured from below or in a stark close-up, their features enlarged to emphasize the individual effort pushing the Soviet Union forward.

Cinema was expected to follow suit, and soon this relatively young art-form was dominated by the products of Socialist Realism. The new Soviet Republic initially fostered a dynamic culture of film-making on grand social themes, exemplified by the works of Sergei Eisenstein, whose Battleship Potemkin (1925), a dramatization of a sailors' mutiny in 1905, is an exemplary work. However, the parameters of sanctioned cinematic style gradually became narrower and narrower; the second instalment of Eisenstein's incomplete Ivan the Terrible trilogy, for example, released in 1958, had a vexed relationship with the censors because of its ambivalently suggestive portrayals of totalitarian power. Approved works from this later era, such as Mikheil Chiaureli's The Fall of Berlin (1950), often presented Stalin as a great and benevolent leader, in this case steering the country through the perils of the Second World War.

Socialist Realism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

The artistic model for Socialist Realism was uncompromising, and laid out by the state. Socialist Realism must be optimistic in spirit, Realist in style, and obviously supportive of the Soviet cause. Often, works were expected to venerate an individual hero of the new republic, whether that meant a state figurehead or, as was more often the case, a member of the laboring classes raised to the level of celebrity such as Alexey Stakhanov, the record-breaking miner on whom George Orwell's character Boxer the Horse (from Animal Farm) was based. Within the narrow stylistic and thematic parameters of Stalinist aesthetics, however, artists of talent and invention continued to find minimal ways to express themselves.

Optimism

Socialist Realism was required to present a highly optimistic image of life in the Soviet State. This was the crucial distinction between Socialist Realism and Social Realism, the larger movement which influenced and to some extent incorporated it: Social Realism was in many cases excoriatingly critical of the conditions it portrayed, as is Ilya Repin's stunning Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870-73). By contrast, the hardship precipitated by Stalinist rule - and, indeed, by civil war during 1917-22 - was not an acceptable subject for critique: artists were required to toe the line in their choice and depiction of subject-matter.

In 1928, for example, Stalin launched the first of his Five-Year Plans, focused on bringing all economic production under the control of the state. This included the mass collectivization of farming through the Kolkhoz scheme, resulting in widespread famine, and a drop in agricultural productivity. Whereas a Social Realist in the vein of the Peredvizhniki artists would most likely have reported this, the Socialist Realist was required to extol the virtues and successful implementation of collectivization. Forced requisition of land, livestock and crops; starvation and psychological trauma: all of these realities were airbrushed from the scene. In their place we find bright color-palettes and alert, well-fed peasants adapting to the task at hand with industry and aplomb, as in Gregory Ryazhsky's The Collective-Farm Team Leader (1932). By a generous analysis, these images were aspirational, presenting life in modern Russia not as it was, but as it could be; one might equally state that these works retained the stylistic veneer of Realism while abandoning reality as a subject-matter.

Realism

When Kazemir Malevich composed his famous Black Square in 1913, he embodied a spirit of radical abstraction that was sweeping across Russia and the West at the time. In the early days of the Soviet Republic, this spirit still found expression, partly because Trotskyist factions within the government continued to extol the virtues of abstraction, arguing that Communist art needed to absorb the lessons of bourgeoise experiment in order to transcend working-class convention, and thus become 'classless'. When Stalin rose to power, however, any such nuance in cultural debate was abandoned in favor of a bloody pragmatism: artists, sculptors, photographers and filmmakers would offer idealized images of political and cultural leaders and of everyday life in the new Russia, in the most conventionally 'realistic' manner possible. The Socialist Realist had to learn how to draw and paint from life, in a highly linear and accurate fashion. Some painting was so lifelike that it became akin to color photography; in a sense, considerations of form and style were abandoned altogether.

Boris Ioganson, a leading official artist of the Stalinist period, summed up the spirit of the age by stating that the locus of creativity in Socialist Realism lay not in the technique of the composition but in the "staging of the picture". The statement is an intelligent and illuminating one, but the contradiction at the center of this version of Realism is clear in his use of the word "staging"; and is evident in works such Aleksander Deyneka's Stakhanovites (1936), which depicts the ideal community of Russian workers. The word "Stakhanovite" is a reference to Alexey Stakhanov, indicating a tireless worker for the Soviet cause - more in the manner of a visionary allegory than a work of Realism. A procession of tall, happy, healthy workers dressed in white appear in front of the Palace of the Soviets, a building on which construction had not started when the painting was composed; it commenced the following year, but was terminated by the German invasion of Russia in 1941.

The Hero

Leading Alexander Deyneka's Stakhanovites is Alexey Stakhanov himself, reputed to have set astonishing records as a coal-miner in 1935, processing 102 tons of coal in a single shift (it was subsequently suggested that he did so with a team of assistants, as part of a staged propaganda exercise). Stakhanov became a national celebrity, the figurehead of a cult of productivity; he even appeared on the cover of Time magazine in December 1935. Stakhanov was venerated as the exemplary "New Soviet Man", the kind of figure on whose shoulders the USSR's future would be built: healthy, muscular, selfless, and enthusiastic, with an unstinting work ethic. Proletarian heroes such as Stakhanov are found all over Socialist Realist paintings, from factory workers and scientists to civil engineers and farmworkers, all embodying the same spirit of individual will directed towards collectivist ideals. This, of course, was another paradox at the heart of Socialist Realism: that the establishment of a collectivist society was seen to require a quasi-religious veneration of the individual.

The same irony can be sensed in the depiction of the new state's leaders. In a pattern repeated across totalitarian cultures throughout the twentieth century, these figures effectively took the place of religious icons in the public imagination, appearing in monumental portraits and posters as semi-deific beings, leading the nation forward by the force of their will and insight. Much of this work was produced by talented painters such as Isaac Brodsky, who in the late 1920s and 1930s composed several paintings of Lenin during key phases of the Russian Revolution, such as Vladimir Lenin 1 May 1920 (1927). These are now amongst the most stylish monuments to the cult of personality that grew up around Lenin and Stalin during the Socialist Realist era.

Support for the State

By the 1930s, the Soviet Union's galleries were bedecked with political portraits, including of the state's two great leaders, Lenin and Stalin. If the statist message behind such work was overt, the subtler propaganda of Socialist Realism was conducted in the guise of genre paintings and still lifes, which had no explicit connection to political themes. Works such as Ilya Mashkov's Soviet Breads (1936) depicted the abundance of everyday life within the communist state; Mashkov depicts loaves of all shapes, designs and sizes, vying for attention beneath a traditional corn decoration surrounding an ornamental loaf incised with the hammer and sickle.

The various subtexts of Mashkov's image sum up some of the paradoxes of the Socialist Realist aesthetic, and indicate the germ of creativity that existed within it. The concession to Russian folk-art in Mashkov's self-consciously naïve composition reflects his connection to radical painters of the pre-revolutionary period such as Mikhail Larionov, one of the artists with whom Mashkov co-founded the Jack of Diamonds group in Moscow in 1910. This group was responsible for defining many of the principles associated with Neo-Primitivism; Mashkov's survival as an artist in Russia up until his death in 1944 thus suggests the surprising range of stylistic influences which Socialist Realism occasionally admitted, provided they were channeled in the right direction. At the same time, the unwitting irony behind the date of this painting's composition cannot be ignored: at the conclusion of collectivization, which had brought famine to vast swathes of Russia's rural poor.

Socialist Realism outside the Soviet Union

As Stalin's international policy became increasingly imperialist in the years following the Second World War, Socialist Realism was exported to the satellite states of the Eastern Bloc, new Soviet republics which had sprung up across eastern Europe in the years following the surrender of the Axis forces in 1945. In the People's Republic of Poland, founded in 1947, Socialist Realism was enforced as state policy from 1949 onwards; a similar timeline applies to the Socialist Republic of Romania, also founded in 1947. As these countries were in political and cultural thrall to the USSR, it is unsurprising that the works of Socialist Realism produced there show little overall stylistic difference from those composed in the preceding decades in Russia, though again, individuals of talent and creativity survived, such as Alexandru Ciucurencu in Romania (who, admittedly, was well-established as a Post-Impressionist painter before 1947). Works composed in homage to the modernization of agriculture under Soviet rule, such as the Polish painter Juliusz Krajewski's Thank You Tractor Operator (1950), are reminiscent of those composed two decades earlier during collectivization in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet conception of Socialist Realism also inspired cultural developments outside Europe, including in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (founded in 1948), and the People's Republic of China (founded in 1949). Chairman Mao's proclamations on the role of the artist in the new Chinese state echoed those of Stalin: "[a]ll our literature and art are for the masses of the people, and in the first place for the workers, peasants and soldiers". In a policy referred to as the "nationalization of oil painting", Chinese artists would study European painting techniques in order to promote Mao's variant of Stalinist cultural nationalism.

Later Developments - After Socialist Realism

Reception in the West

In 1939, in his famous article "Avant-Garde and Kitsch", the North-American critic Clement Greenberg excluded Socialist Realism from the canon of modern Western art, defining it as the ultimate example of "kitsch", art depicting staid and familiar themes in a stylistically orthodox manner, for an ill-educated public. Whatever the prejudices of Greenberg's position - he also derided earlier, Social Realist painters like Repin as "kitsch" - it summed up the general stance on Socialist Realism outside Russia for the following half-century. Indeed, the global history of modern art between 1932 and 1953 continues to exclude Russia to a large extent.

Four years after Stalin's death, his successor Nikita Khrushchev denounced his predecessor's cultural policies as "cruel and senseless": "[y]ou can't regulate the development of literature, art, and culture with a stick, or by barking orders. You can't lay down a furrow and then harness all your artists to make sure they don't deviate from the straight and narrow. If you try to control your artists too tightly, there will be no clashing of opinions, consequently no criticism, and consequently no truth. There will be just a gloomy stereotype, boring and useless." There followed a period referred to as "The Thaw", when artists and writers were allowed greater freedom over the form and content of their work, and increasingly made contacts outside Russia, while foreign literature, art, and music was increasingly tolerated within the USSR. Ironically, this period coincided with the height of the Cold War, but the relative relaxation of Khrushchev's cultural policies was epitomized by the publication of Alexander Solzhenitsyn's One Day in The Life of Ivan Denisovich in 1962. An unflinching account of life in a Stalinist labor camp, it would never have survived the censors before 1953.

In visual art, the most striking works of this period were produced by so-called Non-conformist artists such as Oleg Vassiliev, who combined a Social Realist style with influences from the first-wave Russian avant-gardes of the early twentieth century. Within literature, groups emerged such as the Red Cats, formally inventive poets somewhat akin to the Beats, one of whom, Andrei Voznesensky, appeared alongside Allen Ginsberg at the famous International Poetry Incarnation in London in 1965.

By 1964, Khrushchev had in fact been ousted from power, and Leonid Brezhnev, a truer heir to Stalin's repressive cultural policies, had risen to replace him. It was under Brezhnev that Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia in 1968 to quash the democratizing agenda that had risen in the satellite state during the so-called "Prague Spring". But by the 1980s, and particularly by the time of the last Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev, the orthodoxies of Socialist Realism had long-since dissolved, and an increasingly wide array of work was admitted for publication and display: one such work was Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid's openly mocking The Origin of Socialist Realism (1982), which shows a seated Stalin cradled by a naked muse. The gradual evolution of Russian art away from Socialist Realism following Stalin's death remains a largely untold story in modern art history. As the Polish art critic Agata Pyzik writes: "Socialist Realism remains possibly the most rejected period of Soviet art, identified with pernicious politics and backwards aesthetics. For decades, it was a 'don't touch' moment of art history."