Summary of Social Realism

The Social Realist political movement and artistic explorations flourished primarily during the 1920s and 1930s, a time of global economic depression, heightened racial conflict, the rise of fascist regimes internationally, and great optimism after both the Mexican and Russian revolutions. Social Realists created figurative and realistic images of the "masses," a term that encompassed the lower and working classes, labor unionists, and the politically disenfranchised. American artists became dissatisfied with the French avant-garde and their own isolation from greater society, which led them to search for a new vocabulary and a new social importance; they found their purpose in the belief that art was a weapon that could fight the capitalist exploitation of workers and stem the advance of international fascism. The art period is quite distinct from the Soviet Socialist Realism that was the dominant style in Stalin's post-revolutionary Russia.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Social Realists envisioned themselves to be workers and laborers, similar to those who toiled in the fields and factories. Often clad in overalls to symbolize unity with the working classes, the artists believed they were critical members of the whole of society, rather than elites living on the margins and working for the upper crust.

- While there was a variety of styles and subjects within Social Realism, the artists were united in their attack on the status quo and social power structure. Despite their stylistic variance, the artists were realists who focused on the human figure and human condition. Social Realists built on the legacies of Honore Daumier, Gustave Courbet, and Francisco Goya in their politically charged and radical social critiques.

- While modernism is most often considered in terms of stylistic innovation, Social Realists believed that the political content of their work made it modern. Social Realists turned away from the painterly advancements of the School of Paris.

Artworks and Artists of Social Realism

Cover image for the New Masses

Committed to Marxism and communism, William Gropper drew vast numbers of illustrations for such radical publications as the New Masses and the Communist Party's Daily Worker. Wanting to reach the greatest number of working people, Gropper and others created prints and graphics for radical magazines, which were easy to distribute. Here, Gropper engaged the revolutionary visual rhetoric of the monumental, triumphant worker who both ideologically and physically dominates the puny clerics and capitalists in the lower left corner. Religion, in cahoots with capital, seeks in vain to contain and repress America's worker who is represented almost as a King Kong figure breaking free of his chains; the movie King Kong debuted in 1933. The idea of industrial servitude and slavery are also communicated by the chain links that the worker powerfully splits apart. Gropper's message is as stark and clear as is his choice of black and white coloration.

Ink on paper

Aspects of Negro Life: Song of the Towers

A member of the Communist Party, this is Douglas's fourth panel from a series covering the transition between human slavery and modern industrial enslavement; the final, fifth panel was to show Karl Marx amongst African-American workers leading them to a better proletarian future. At the work's apex, a saxophonist stands triumphantly with his instrument held high above his head, far above the green grasping hands that would draw him back into slavery. Yet his triumph is fleeting, as the industrial cog on which he stands will carry him back into the depths of the city and society; industrialism and mechanization are not friends of the American worker. Beyond the man's reach, in the far distance, stands the Statue of Liberty symbolizing the unfulfilled promises of universal freedom. Song of the Towers showcases Douglas's signature style of concentric, radiating circles that are punctured by bold silhouetted figures.

Oil on canvas - Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library

Death (Lynched Figure)

Isamu Noguchi's early sculptural works dedicated to social concerns, which align with the artistic Left, are often overlooked in deference to his abstract statuary and furniture design. As compared to other Social Realists, Noguchi employed a more modernist vocabulary instead of particularizing the figure and its facial features. Considered a major early piece by Noguchi, Death (Lynched figure) testifies to the artist's progressive racial views and strong social commitment, which position the sculpture within the concerns of Social Realism. Noguchi modeled the painfully contorted figure hanging from a rope on a photograph of African-American George Hughes being lynched above a bonfire, writhing in agony; Hughes was hanged in Texas in 1930. The horrifying photograph of Hughes was later reproduced in the Communist magazine, Labor Defender, which is where Noguchi saw it. In terms of form, the sculpture is unusual since Noguchi suspended the figure above the ground on a metal armature. Noguchi created this sculpture for a 1935 exhibition organized by the NAACP to protest the national rise in lynching and also to pressure President Franklin D. Roosevelt to enact legislation prohibiting such vigilante violence; Roosevelt did not. Concurrently, the communist arts and cultural organization known as the John Reed Club held its own anti-lynching exhibition. While Noguchi's sculpture was well received, some critics reacted harshly to it, revealing their own racism by claiming the artist was not native-born and, in one instance, referring to the provocative sculpture as "a little Japanese mistake."

Monel, steel, wood, and rope - The Isamu Noguchi Museum

The Working Day; Struggle for a Normal Day Repercussion of the English Factory Acts on Other Countries

By reproducing Marx in mass-distributed magazines, Hungarian-born Hugo Gellert sought to gain a wider audience among the working class and perhaps rattle the nerves of upper class society. Social Realists most often romanticized and idealized the figure of the male worker; Gellert's is a prime example of this trend. Here, Gellert renders a Caucasian laborer and an African-American laborer standing back to back. Originally published in the New Masses, the pairing of monumental men was placed above the caption: "Labor with a white skin cannot emancipate itself when labor with a black skin is branded." The men stand strong, fused together as if a unit, and are shown wearing workers' overalls, which reveal their muscular arms. Their taut bodies, their position of being pressed together, along with their rather phallic tools, a pick and a wrench, create a homoerotic quality to the image. Images of physically strong working men were prevalent throughout Social Realist works in order to present labor as invincible against capital.

Demonstration

Born and based in Argentina, Antonio Berni was known for his socially engaged figurative painting, rooted in his Marxist viewpoint for interpreting society. During the 1930s, Argentina was in great political turmoil. David Alfaro Siqueiros published a "Call to Argentinean Artists," which profoundly affected Berni who went on to assist the Mexican Muralist on the mural Plastic Exercise (1933) for a private patron outside of Buenos Aires. During the years 1934 to 1937, Berni painted approximately 40 easel paintings of mural proportions including Demonstration, which depicts a crowd of unemployed men and women. Set in the provinces, the crowd marches towards us down a main street; one worker carries a sign aloft stating their dual demand for bread and work. Berni has rendered the many faces of the unemployed pressed up against the picture plane in order to directly confront the viewer. The many faces are painted in a sculptural manner, with a dramatic application of light and shadow, and are rich in detail. The artist eschews painting the dispossessed as falsely heroic or sentimental and instead shows the solidarity of the poor.

Tempera on burlap - Private Collection

Artists on the WPA

The three Soyer brothers, Isaac, Moses, and Raphael, were all important Social Realist artists. Here, Moses Soyer highlights solidarity and the communal bonds of artists on the New Deal projects by painting them within a common studio. Each artist paints or serves as a model for another artist in a collegial manner. The artists' efforts are collaborative as they together work on their murals, which were made to serve the public rather than for private gain. By the early-20th century, New York City was simultaneously the center of artistic training in the United States and the bedrock of leftist politics, which involved many sons and daughters of Jewish immigrants. Moses Soyer, born in Russia, was all three: Jewish, an artist, and on the Left.

Soyer composed his celebrated Artists on the WPA as if it were a stage set with the curtain having just lifted to reveal the proceedings, inviting us into this artists' studio. The floor of Soyer's studio slants upward, permitting a greater view of the room and the painters at work. Arranged in a semicircle, four painters both male and female, work on oversized canvases that most likely are parts of murals. Each artist paints in the style of the government-preferred American Scene, with its requisite realistic figures and pleasurable depictions of productivity and harmony, blocking out the contemporary realities of unrest and destitution. Soyer creates subtle subterfuge by showing artists as laborers, banded together and diverse in population. As opposed to the more common portrayal of artists as romantic heroes alone and outside of society, Soyer's artists seem to have a positive social role. The sense of group activity echoes the collective actions of artists through picketing, protests against social injustices, and demands for permanent recognition by the government.

Oil on canvas - Smithsonian American Art Museum

Presents from Madrid

Paraskeva Clark was twice an immigrant having been born in Russia, then moving to France for a decade, and ultimately settling in Canada. Presents from Madrid was Clark's first artistic exploration of a public political subject, namely the Spanish Civil War. Here, Clark openly declares her opposition to Spanish leader General Francisco Franco. The painter depicts a number of objects related to the war against fascism, such as a cap from the Canadian Mackenzie-Papineau Brigade; a medieval Spanish missal; a red scarf decorated with three men who represent the Spanish Popular Front; and a Republican brochure. These were mementos that had been sent to her from Spain. Clark chose to create a still life, a genre traditionally associated with the domestic sphere and the feminine arts. The genre was not popular within Social Realism, which was overwhelmingly didactic, narrative, and concerned with the human figure. Through her choice objects, which are indicative of her political beliefs, Clark moved her work into what was traditionally the male sphere of the public and the political.

Watercolor over graphite on wove paper - The National Gallery of Art, Ottawa

An American Tragedy

Philip Evergood's An American Tragedy has been hailed as the "archetypical work of Social Realism" for its bold execution and equally bold subject matter of labor conflict. Here Evergood's heavy line, strident colors, and figurative style are deliberately crude and caricatured, a style called the "Proletarian Grotesque" which was inspired by Spanish artist Francisco Goya's anti-authoritarian stance and expressive line. The scene takes place in South Chicago's Republic Steel plant which was unionizing. Workers armed with sticks show aggressive solidarity with its integrated workforce of men and women, African Americans, Caucasians, and Latinos against the attacking police. At center, a red-haired man and his pregnant Latino wife stand together against the police who killed 10 workers on that day and injured 100 others. Evergood had suffered his own beating at the hands of the police when participating in a sit-down strike organized by the Artists' Union. Evergood asserted, "I don't think anybody who hasn't been brutally beaten up by the police badly, as I have, could have painted An American Tragedy."

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

The Migration of the Negro (One of the Largest Race Riots occurred in East St. Louis), #52

Created when the artist was in his early 20s, Jacob Lawrence's epic series is comprised of 60 panels, which are evenly split between New York's Museum of Modern Art and Washington, DC's Phillips Collection. Lawrence's subject matter is the Great Migration of African Americans from the deep, rural South to the urban North during the 1910s. Promises of industrial jobs and greater freedom propelled the migrants to leave the South, and they were met with overt racism, leading to virulent race riots in St. Louis, substandard housing, grueling, subhuman industrial work, and exclusion from labor unions due to race. Lawrence was the son of migrants and so was drawing both from his family's and community's history.

Lawrence primarily drew his stylistic innovation from his immediate community in New York's Harlem. As he did in much of his early work, Lawrence has flattened the picture plane and any sense of perspective rendering the silhouetted figures as if they were two-dimensional. The works are enlivened through Lawrence's distinct use of vibrant and bright colors, which are not modulated.

Casein tempera on hardboard - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Beginnings of Social Realism

During the 1920s, American artists searched for a greater importance within society. The presence of Mexican muralists Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco in New York City, together with the widespread teachings of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin, served as inspiration to the emerging artists. Later, with the lingering effects of the Great Depression of 1929, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration (WPA) provided many struggling artists with patronage, a sense of community, and the mandate to paint realistically. Within the above historical context, a very large and diverse group of artists later called the Social Realists joined together to publish magazines, organize unions, convene artists' congresses, and publicly agitate for the importance of their revolutionary work, the role of the artist within society, and radical anti-capitalistic change for America.

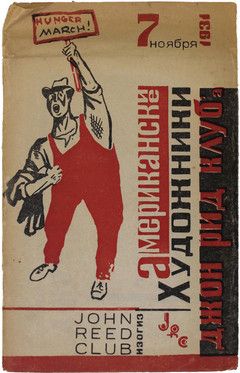

New Masses and the John Reed Club (1931)

In the 1920s, several artists committed to leftist politics launched New Masses, a radical cultural publication that was tied to Communist Russia. These revolutionary artists also established the John Reed Club. The club's name paid tribute to American journalist John Reed (1887-1920), the author of Ten Days That Shook the World who chronicled the Russian Revolution. The John Reed Clubs (60 in total throughout the United States) promoted the establishment of a proletarian society through their cultural events. Among the better-known members of the Club were Max Weber, Hugo Gellert, William Gropper, Moses Soyer, and Raphael Soyer. According to later reminiscences by involved artists, it was through the John Reed Club that they developed a progressive worldview. Teachers at the John Reed Club in New York City included the Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, theorist Lewis Mumford, art historian Meyer Schapiro, artist Ben Shahn, and Louis Lozowick who was the main theorist of the group. The John Reed Club never dictated a specific artistic style or subject matter, yet mandated that artists align themselves with the poor and dispossessed, fight for racial justice, and oppose fascism.

Museum of Modern Art and Social Realism

The early 1930s saw the opening of several key museums and art galleries that went on to exhibit the art of the Social Realists, such as both New York's Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. In 1930, Diego Rivera had a one-man show at MoMA, which included the artist painting portable murals on site. Many of the Social Realists visited the revered Rivera as he painted. Two years later, MoMA presented a highly controversial exhibition inviting artists, including Social Realists, to create mural studies for potential projects. Ben Shahn, Hugo Gellert, and William Gropper did not hold back in their biting social criticism. Shahn's The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti (1931-32), as well as caustic satirical works by Gellert and Gropper that attacked the moneyed, heads of state, and social elites, or in other words, the social types who controlled society and sat on MoMA's Board of Directors. Their works created a storm of criticism that Gropper triumphantly chronicled in his New Masses article "We Captured the Walls!"

The Popular Front

The Russian Communist Party announced the political period known as the Popular Front in 1935, aiming to create a united political front to eradicate fascism that, with the election of Hitler as Germany's Chancellor in 1933, was seen as a greater enemy than capitalism. Under the slogan "Communism is Twentieth-Century Americanism," the Communist Party sought to unify left and liberal Americans. The Popular Front was more welcoming to liberal artists who worked for social equality, rather than for the radical transformation of America into a socialist state. This historical event, driven by Russia, impacted American artists by allowing the progressives who were not extreme radicals to join the cause. A greater number of artists took up the theme of anti-fascism in their art and lessened the hardline commitment to worker-based art and imagery.

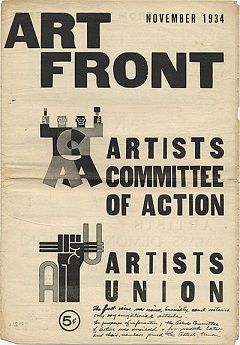

The Artists' Union and Art Front

A great concern during the 1930s was labor unions and labor organizing. Social Realists who considered themselves to be workers established their own labor union called the Artists' Union. The Artists' Union was an affiliate of the dominant labor union of the time, the Congress of Industrial Organizations. Bernarda Bryson, Ben Shahn, and Stuart Davis, among other members of the Artists' Union, together agitated for permanent federal art programs and better wages for artists under the New Deal. They were also part of the fight against racism, fascism, and war. Art Front was its radical magazine, complete with articles, photographs, essays, and illustrations.

The American Artists Congress

The American Artists Congress convened in 1936 and Social Realists were among the hundreds in attendance. This was part of the Popular Front's attack against global fascism with the rise of Adolf Hitler and, even locally, with Father Charles Coughlin stirring anti-Semitic sentiments. In addition, artistic censorship was on the mind of many with Nelson Rockefeller's infamous cancelations of Diego Rivera's mural in Rockefeller Center (1933) and Ben Shahn's mural for Riker's Island Penitentiary (1934). Pressing social events of the day held sway rather than aesthetic debates. For example, African-American painter Aaron Douglas criticized socially conscious artists for using African Americans as symbols. An exiled artist from Nazi Germany reported on the events unfolding in Europe. The economic plight of artists was also an issue passionately discussed. The Union successfully inspired artists, giving them a sense of social importance and of being part of a greater, global community.

Social Realism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Despite disparities in style, painters, sculptors, illustrators, and printmakers all were committed to realism and figuration; in fact, it's hard to imagine a Social Realist work that did not focus on the human condition and the human figure. Also common amongst these diverse voices was their commitment to labor, which explains the emphasis on idealizing the worker in art. The artists sought common cause with their subjects and sought to use "art as a weapon," in the words of Diego Rivera, to radically transform society.

The Glory of the Heroic Worker

Unlike the Ashcan School artists, where members of the working class were social outcasts, Social Realists envisioned the worker as a social hero. Empowering the worker physically and making him the focus of artwork communicated the centrality of the laborer to a new worker-based society. Greater emphasis was placed upon the industrial worker over the agricultural worker since this paralleled the economic shift from a farm-based economy to an industrial society. Clad often in workers' overalls holding tools, their jaws squared and faces firm and determined, the worker-hero is shown as the backbone of America and the means to a better future. Occasionally, the worker-hero is shown adjacent to his wife who is rendered diminutive to him in stature, wearing emblems of domesticity such as an apron and subordinate to his authority. Much rarer are images of women as industrial workers.

Sympathy for the "Forgotten Man"

Social artists most often depicted society's outcasts and the marginalized, such as the urban poor, racial minorities, immigrants, and ghetto residents. Often these men were pictured alone without the safety and sanctity of the family unit. Social Realists gave attention and voice to these "forgotten men," as they were called, with empathetic imagery of their struggles. These outcasts appear as the direct opposite of the worker-hero because the former lacks neither personal agency nor power to control his destiny. Instead of being upright and muscular, his body collapses down into itself and is comprised of more rounded forms: a slacken head, slumping shoulders, bent knees. In this manner, his body communicates a forlorn sense of hopelessness and destitution.

The Struggles of Rural America

Overwhelmingly, Social Realism was an urban-based movement created by urban-based artists. However, with the Dust Bowl and other traumatic events caused by poor land management, the sharecropper system and absentee landowners were within the realm of social commentary. The pairing of the agricultural with the industrial laborer was a potent social and political theme of the time and Worker-Farmer political parties were being established. Such artwork, which highlighted the rural poor, ruined lands, and devastation of nature, vehemently countered the chauvinistic Regionialist artists (John Steuart Curry, Grant Wood, and Thomas Hart Benton) who championed the sanctity of rural America, the natural landscape, small town life, and the farmer.

Modernist Connections: Social Surrealism

While Social Surrealists worked alongside the Social Realists, the latter claimed to be the political outspoken art style, yet in fact, it was the Social Surrealists who worked in the more radical style. Radical politics and radical times necessitate a radical form of art, and in the 1930s to mid-1940s, Surrealism was one such form of painting. They believed that liberation of the mind and liberation of the individual would lead to the end of political and social oppression. Social Surrealists used key stylistic techniques of European Surrealists, such as condensing time and space, perfecting a montage of elements, and juxtaposing objects in an illogical manner. For example, Oswaldo (Louis) Luigi Gugleimli expressed his concern with Manhattan's impoverished neighborhoods with a sense of empathy that he developed from growing up in a poor Italian immigrant section of the city. Philip Evergood's body of work has been referred to as both Social Realist for his subject matter and Social Surrealist for his exaggeration of figures, heightened colors, and vivid brushstrokes.

Socialist Realism in Russia and Germany: Totalitarian Art

The Social Realists' openness to a variety of styles and subjects stands in stark contrast to Soviet Socialist Realism, which sought to uphold the Russian political structure through stridently didactic images of workers painted with great uniformity. In both Russia as well as Germany, doctrinaire imagery of the heroicized, classically inspired body promoted Joseph Stalin's and Adolph Hitler's social visions. In Germany, Hitler encouraged the painting of the nude with hyperrealistic perfection to communicate the perfect Aryan body. In contrast, the nude was never a mainstay of American Social Realists, whose figures were based more upon genre painting than classical ideals.

Later Developments - After Social Realism

The Changes in the Political Landscape

Starting in the 1930s, the United States government became dramatically less supportive of Russia, which was once the country's ally. This chilling of international relations and attacks against communism directly impacted artists and art movements. Due to persistent rumors that "reds" had taken over the Federal arts programs, the government established the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1938, which investigated numerous artists, among other individuals and groups, searching for possible communist infiltrators. This threw shockwaves throughout the artistic left. An even deeper blow was the 1939 Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression pact, which caused many artists to give up their idealization of Russia as a utopia. While some remained blindly supportive of Stalin, others became more committed to FDR and democracy. With the start of WWII, America's economy kicked into recovery and many industrial jobs became available but were still racially segregated. This postwar prosperity for some Americans also distanced many people from the Soviet model.

The Replacement of the Avant-garde

It is popular to think of Abstract Expressionism as the sole art form of the mid-1940s and 1950s, totally eclipsing realism and political content in art. But this wasn't the case. In fact, many artists such as Ben Shahn, Jacob Lawrence, and Isaac, Moses, and Raphael Soyer, among numerous others, continued to exhibit their works during the Cold War era. Some artists, such as Philip Guston, did see their work evolve into abstraction. It is true that Social Realism was no longer the art of the avant-garde, but it did not vanish. However, the John Reed Club, the Artists Union, and Art Front ceased to exist in part due to internal factions and in part due to the awareness of the Holocaust and the acceptance by many that Stalin was a murderous despotic dictator, rather than a heroic figure.

However, realism and socially conscious art making never died, but these continue to be strands within contemporary art that include names such as Sue Coe and Mike Alewitz. Coe creates narrative series of prints and paintings that address difficult issues such as rape and injustice to women. Alewitz, who witnessed the killing of four young people at Kent State, has gone on to become a muralist for labor unions, social causes, and political actions. He is perhaps America's leading political muralist. In terms of scholarships and exhibitions, starting in the 1980s with publications by Alejandro Anreus, Matthew Baigell, Andrew Hemingway, Patricia Hills, Helen Langa, Diana Linden, and JonathanWeinberg, there has been a resurgence of interest in Social Realism.

Useful Resources on Social Realism

- The Social and the Real: Political Art of the 1930s in the Western HemisphereOur PickBy Alejandro Anreus, Diana L. Linden, and Jonathan Weinberg

- Rethinking Social Realism: African American Art and Literature, 1930-1953Our PickBy Stacy I. Morgan

- Social Realism: Art as a WeaponBy David Shapiro

- Mexican Painters: Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros, and Other Artists of the Social Realist SchoolBy MacKinley Helm