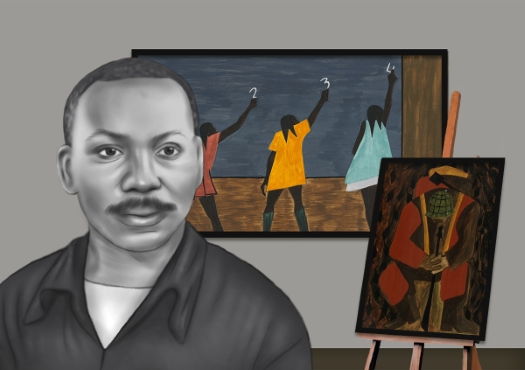

Summary of Jacob Lawrence

Achieving success early in his career, Jacob Lawrence combined Social Realism, modern abstraction, pared down composition, and bold color to create compelling stories of African American experiences and the history of the United States. Drawing on his own life and what he witnessed in his Harlem neighborhood of New York City, Lawrence strove to communicate human struggles and aspirations that resonated with diverse viewers. Coming to artistic maturity during the waning of the Harlem Renaissance and the waxing of Abstract Expressionism, Lawrence charted a unique path, telling poignant stories of migration, war, and mental illness, among others, and would become a powerful influence for younger African American and African artists. While often drawing on the specific experiences of African Americans, Lawrence's long-running and prolific career produced an oeuvre that speaks dramatically, graphically, and movingly to viewers of all colors and persuasions.

Accomplishments

- Early in his career, Lawrence's artistic process relied on a vast amount of historical research. Spending hours at the public library pouring over historical texts, memoirs, and newspapers and attending history clubs that were then popular in Harlem, Lawrence translated these histories into images and linked them to contemporary political struggles both in the North and the Jim Crow segregated South, reinvigorating traditional history painting.

- Lawrence often worked in series, creating numerous individual panels, to tell a story. Influenced by avant-garde cinema, Lawrence's series often have a montage-effect, but he used structural strategies, such as a unified color palette and recurring motifs, to connect the individual paintings into a coherent whole.

- Lawrence borrowed strategies from print media to make his stories based in experiential reality as compelling as possible . He paired long, descriptive captions with his paintings as was common in photo magazines and books in the 1930s and 1940s. Additionally, Lawrence used flat, unmodulated colors in large planes that had the quality of print graphics.

- Lawrence's use of abstraction in depicting the characters of his stories allow those stories, even if historically specific, to have more universal appeal, as the viewer can imagine him or herself in similar positions. Lawrence's ability to imbue the particular drama of everyday life with the gravitas of collective, or universal, humanity is one of his greatest artistic feats.

Important Art by Jacob Lawrence

The Frederick Douglass series, Panel 28

The full text of Panel 28 from The Frederick Douglass Series reads: "A cowardly and bloody riot took place in New York in July 1863 - a mob fighting the draft, a mob willing to fight to free the Union, a mob unwilling to fight to free slaves, a mob that attacked every colored person within reach disregarding sex or age. They hanged Negroes, burned their homes, dashed out the brains of young children against the lamp posts. The colored populace took refuge in cellars and garrets. This mob was part of the rebel force, without the rebel uniform but with all its deadly hate. It was the fire of the enemy opened in the rear of the loyal army."

Panel 28 uses simplified forms, a limited color palette, and a clear narrative progression from left to right in tandem with evocative, descriptive text. A group of freed slaves huddle in a shelter, watching the carnage of a Civil War anti-draft riot with expressions of horror and sorrow. Lawrence divided the panel into three dramatic groups. The first group depicts two adults and a child, wide-eyed with fear as they witness the brutality of the riot. The second, middle group shows an older woman, symbolizing an older generation with memories of slavery and the commonality of violence, sheltering a young child who, perhaps unused to such scenes, is seemingly distracted, and grasps the woman's thumb. The third grouping, a mother, father, and infant, symbolizes the hope and fear of a generation born at the cusp of great change and the promise of freedom throughout the United States tantalizingly at hand. Lawrence later recalled the work's important political gestures as "some of the most successful statements I have made in my life ."

Working with a palette of browns, bright red, yellow-orange, black, white, and blue, Lawrence created his figures as non-naturalistic color blocks, their limbs elongated, their torsos concealed beneath blocky clothing, and their facial features simplified to eyes and mere outlines of a nose and mouth. These compositional decisions eliminate extraneous background details that would take away from the poignant emotions of the narrative. Art historian Elizabeth Hutton Turner has said of Lawrence's works in series that they were conceived as "image and word" together, with the works' "poetry" emerging from the "repetition of certain shapes" linking one panel to the next. In Frederick Douglass, the woven basket, made by slaves, acts as a reminder of slave labor, the work of the Black American journey to freedom, and the continual presence of an oppressive past even in a seemingly safer present. The red flower symbolizes hope, and its appearance in Frederick Douglass panels suggests the promise of a better life, even in the most dire of circumstances.

Casein tempera on hardboard - Hampton University Museum, Virginia

The Migration of the Negro, Panel 22

The full text of Panel 22 from The Migration of the Negro series reads: "Another of the social causes of the migrants' leaving was that at times they did not feel safe, or it was not the best thing to be found on the streets late at night. They were arrested on the slightest provocation."

Lawrence's most famous narrative series, his 60-panel The Migration of the Negro, perfected his signature combination of historical storytelling and abstracted style. In Panel 22, Lawrence used an interplay between linear design and unmodulated color planes to suggest the indignities of Black imprisonment in the pre-Migration-era American South. The incarcerated men are depicted as large, imposing figures, with their heads hanging down, and their broad backs and shoulders extending almost the width of the panel. Despite their size, their immobility suggests their disempowerment in the face of a racist law enforcement and judicial system. Trapped behind bars, with golden handcuffs linking them one to the next, they appear like chattel. The men's slumped shoulders and the dramatic color contrast between the darkness of the men's clothes and grim prison interior, and the bright blue sky beyond the prison confines suggest the men's longing for the freedom they cannot access. Yet, in Panel 22, Lawrence implies that even if the men reached the northern United States and the world of blue sky beyond the prison, ultimately, the men couldn't outrun the root cause of their imprisonment. The echo between the pinstripes on the far-right man's pants and the vertical bars over the jail cell window suggest that as long as racism dictates penal strategy, the men will remain targets for persecution.

Tempera on gesso on composition board - Museum of Modern Art, NY

This is Harlem

With This is Harlem, Lawrence transformed a busy Harlem neighborhood into a series of geometric abstract planes connected to each other by a limited, consistent color palette of brown, blue, yellow, red, black, white, and burnt-red-orange tones. On the roof of the buildings, rectangles and triangles in red, yellow, brown, and black create a back-and-forth interplay between abstraction and figuration. They appear to be chimneys and various structures and at the same time suggest geometric, abstract paintings. Similarly, the human figures populating the Harlem landscape, created with minimal detail and in the same unmodulated color tones Lawrence used for the landscape, appear to dissolve into abstract color planes as much as they represent unique actors, going about the business of daily life.

This is Harlem demonstrates Lawrence's commitment to depicting the intricacies of Black life in Harlem, in particular the social and religious importance of the church and church community. As a predominantly white-toned building, composed with triangular and horizontal rectangular shapes, the church stands out from the painting's other buildings, indicating the centrality of it to African-American life. Similarly, Lawrence used repeated geometric shapes, colors, and references to Christian iconography to suggest the pervasiveness of religion in Harlem, extending from the church and into the secular world of everyday life. For instance, the yellow, blue, and red abstract geometric shapes composing the church's stained glass windows parallel the yellow, blue, and red abstract shapes which create the surrounding apartment units, and the iconography of the cross can be found not only on the church itself, but also in the shapes of the telephone poles and fire escapes.

Gouache on paper - Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution

Victory

In Victory, Lawrence uses a single figure, crafted from a minimal assemblage of burnt orange, brown, yellow, and green color blocks, to illustrate the moral ambiguity of wartime. Though ostensibly celebrating the conclusion of the Second World War, the soldier's head hangs in sorrow. His powerful, hulking frame dominates the panel surface, but slumps, his head bowed over his weapon as if in prayer.

Many panels in the War series exemplify Lawrence's statement in 1945 that "When the subjects are strong, I believe simplicity is the best way of treating them ." Having experienced the Second World War in the U.S. Coast Guard, Lawrence wanted the emotions experienced by both soldier and civilian. In Victory, Lawrence captured the complicated emotions of war's conclusion, as the soldier appears not to revel in the news of victory, but instead to contemplate perhaps the human cost which led to such celebrations, his own role in war's slaughter, or even just to wearily express simple relief at surviving the ordeal.

Egg tempera on hardboard panel - Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Hospital Series: Sedation

Sedation depicts psychiatric patients contemplating the simultaneous numbness and psychological release of sedation. The men's faces are drawn, with the oppressiveness of mental illness signified by the men's downcast eyes, drooping jowls, limp hair, slumped shoulders, sinuous, elongated torsos, and drab pajamas. Lawrence painted the Hospital series after his discharge from his year-long stay in the psychiatric ward at Hillside Hospital in Queens, New York. He attributed an ability to feel things "through his eyes" after his hospitalization, with his works attempting to capture states of consciousness rather than merely narrate a scene or capture an expressed emotion.

Lawrence constructed Sedation to question whether it was mental illness or its treatment which imprisoned the afflicted. The blue, yellow, and red pills are arranged on a white towel within what appears to be a vitrine. The patients gaze at the pills without being able to access them, their looks of despair a testament to the medicalized relief they can only contemplate but not reach. Alternatively, Lawrence's decision to place the pills within an enclosure suggests future imprisonment. Should the patients open the door to sedation treatment, relief may be found but at the expense of freedom, locking them into the cycle of needing sedation and medical management to cope with their illnesses.

Lawrence's depiction of patients at Hillside in various stages of psychological distress, doing activities collectively, and engaging with the therapeutic process is, in the words of art historian Lizzetta LeFalle-Collins, a "marked departure from his other works" as the characters are "neither courageous nor hopeful for their future but resigned." Critics praising Hospital works pointed to the increased psychological depth, social significance, and artistic skill and maturity portrayed in the series' panels, aligning Lawrence with previous modernist masters.

Casein tempera on paper - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Struggle....From the History of American People: No. 23; ...if we fail, let us fail like men, and expire together in one common struggle...Henry Clay, 1813

In panel 23, Lawrence depicts a battle of the War of 1812, but the consequences of battle are reduced to one, single death. The overlapping, craggy planes of grey, black, and white, intercut with jagged black lines, suggest the smoke of battle and chaos of conflict without depicting figures themselves. Lawrence portrays the central individual at the moment of his death, a sharp gestural line signifying the saber or bayonet from an unseen hand piercing the man's eye, with the red stream of blood and the man's yellow-toned flesh stark against the white and grey planes of battle which both support and envelop him as he falls to the ground. By depicting one man's death at the hands of an anonymous, abstract and all-encompassing enemy, panel 23 illustrates both the singularity of death and its ultimate inconsequence in the grander scheme of war and national self-definition.

As much as Lawrence intended to depict the historical arc of American history, to record, in his words, "the struggles of a people to create a nation and their attempt to build a democracy," he also attempted to capture a sense of psychological interiority. Art historian Richard J. Powel argues that while Lawrence depicted "America's military shortcomings during the War of 1812," he also harnessed the abstract examples of gestural abstractionists like Robert Motherwell and Franz Kline to portray something "social and/or behavioral." The jagged lines and fractured compositional surface become a surrogate for a more universal statement about the "uphill battles" of life and general feelings of loss and resignation.

Egg tempera on hardboard - Collection of Dr. Kenneth Clark

Two Rebels

Lawrence painted Two Rebels amid the riots and marches related to desegregation in the American South, marking the image as one of his more directly politicized artistic responses to racial unrest. In May of 1963, demonstrations against segregation in Birmingham, Alabama turned violent, and Lawrence captured the mood in a surreal, exaggerated composition.

Two Rebels depicts two Black men forcibly arrested and escorted to jail by four white police officers. Disembodied heads, representing a leering audience to the arrests, float in the background; the heads' surreal and menacing appearance are characteristic of the unsettling demons and violent dogs populating Lawrence's more contemporary political works in the 1960s. The two arrested Black men are afraid, and the contrast between their spindly hands and larger frames point to their impotence to act and foreshadow the skeletons they may become under police custody. The officers' nightsticks are exaggerated such that the loop at its end appears as if a noose, linking the upheavals of the 1960s Civil Rights movement to the history of violence perpetrated against Black men.

Two Rebels stands as both as specific indictment of segregation and police response to non-violent demonstrations and as a general comment on human behavior circumscribed by oppressive social systems.. According to art historian Patricia Hills, "Lawrence saw [his] civil rights paintings as not different in kind from his other work," and scholars generally note that Lawrence never viewed himself as an activist but rather as a "humanist," who used the struggles of African-American history to symbolize universal struggles.

Egg tempera on hardboard - The Harmon and Harriet Kelley Foundation for the Arts

The Builders

In his later life, Lawrence often returned to a theme which had interested him since the 1940s: builders. In these paintings, inspired by Harlem cabinetmakers Lawrence associated with in his early WPA arts workshops, men and women of all races traverse the composition in vertical and horizontal configurations, building an unspecified monument or structure. Reminiscent of the works of Stuart Davis, in their overall use of flat color planes and abstract shapes to equally create builder, tool, and structure-in-progress, Lawrence's builder images dissolve the boundaries between foreground and background space, and prevent clear demarcations between and among depicted forms. Here Lawrence depicted a collective of old, young, Black, White, male, and female workers who build, saw, sew, and adjust construction materials. The finished or anticipated project is undefined, leaving the viewer instead with work and labor, the means of production, as central subjects, rather than the completed, built, end.

Lawrence used depictions of the American worker community to symbolize a universal desire to construct one's destiny, with figures of all races together creating, building, and shaping the space of the surrounding world. With fewer color tonalities, looser figural definitions, and less attention to clearly-demarcated boundaries between foreground and background space, Lawrence's late career builders paintings displayed a greater compositional freedom.

Gouache on paper - Collection of Safeco Corporation, Seattle

Biography of Jacob Lawrence

Childhood

Jacob Armstead Lawrence was born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to Jacob and Rosa Lee Lawrence, who separated in 1924. Lawrence's parents originally hailed from South Carolina and Virginia, and his family made their way northward to New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and eventually Harlem, New York. The Lawrence family's relocation was emblematic of the World War I-era "Great Migration" of African-Americans out of the oppressive conditions of the Southern United States to the relative safety and economic opportunity promised in the Northern states.

The oldest of three siblings, Lawrence and his brother and sister were placed in foster care in Philadelphia from 1927 to 1930 while his mother worked in New York City. By 1930, at the age of thirteen, Lawrence and his siblings were reunited with their mother, who relocated the family to the Harlem. It was in Harlem that Lawrence first began to experiment with art, creating non-figurative designs and objects in an arts and crafts workshop operated by the local settlement house. Lawrence turned to art less out of a sense of creative "calling" and more as a way to keep himself occupied in the tenement neighborhood of his younger days. Though Lawrence's mother had hoped that Lawrence would become a postman, Lawrence dropped out of high school at age 17 to pursue an artistic career. He was unable to join Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal Works Progress Administration (WPA), an integral source of income to artists during the Great Depression, until the age of 21, and so supported himself and his family through turns as a printer, newspaper deliverer, and construction laborer until 1938, when he secured a position in the WPA and Federal Art Project (FAP)'s easel division.

Early Training and Work

Lawrence was, in art historian Leslie King-Hammond's words, the "first major artist of the 20th-century who was technically trained and artistically educated within the art community in Harlem," and she described Lawrence as Harlem's "biographer." Harlem, the cultural locus of Black American life following the Harlem Renaissance, was itself an integral subject for Lawrence's work. Though Lawrence arrived in Harlem at the tail end of the Harlem Renaissance, Lawrence's early education represented the waning influence of its ideologies, as Lawrence's most significant teachers were Harlem Renaissance luminaries. Charles Henry Alston, Lawrence's first mentor and his teacher at the WPA's Harlem Art Workshop, who came to view Lawrence like his own son, was an artist who came of age embracing the teachings of Alain Locke, whose 1925 The New Negro articulated the Harlem Renaissance artistic philosophy whereby African-American artists should seek inspiration from an African, ancestral past. Lawrence also trained with and was significantly influenced by Harlem Renaissance sculptor Augusta Savage, who instructed Lawrence both at her Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts and at the Harlem Art Workshop. Lawrence's interest in depicting scenes from black American history and from the Harlem world around him, as well as the Egyptian-like angularity of his figures and his later visual references to African art, ultimately reflect the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance.

In his early years, Lawrence was so keen to learn about the history of art, that he would walk from his home in Harlem to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1935, Lawrence met Charles Seifert, lecturer and historian, who allowed Lawrence access to his personal library of African and African-American literature and encouraged Lawrence to seek out the textual resources on African history in the Arthur Schomburg collection at the 135th street branch of the New York Public Library (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture). Sources Lawrence studied in the Schomburg collection became the basis for his most well-known and best-regarded works: his historical works in series. In each series, such as his Toussaint L'Ouverture, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and The Migration of the Negro, Lawrence coupled panel paintings with descriptive captions which collectively narrated either the biography of a notable historical figure or a significant historical event. Lawrence maintained that neither money nor a prominent museum acquisition drove his historical panels, but rather a desire to tell, display, and celebrate the depicted historical events.

Cinema and Social Realist painting were powerful influences on Lawrence's works in series. Jay Leyda, Lawrence's friend and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York's first film curator, introduced Lawrence to Russian and German interwar cinema, and these cinematic models informed Lawrence's scenic construction of each series' narrative progression as an assemblage of dramatic moments, each crafted for heightened emotional impact. Lawrence's connections to the Works Progress Administration (WPA), with its historical emphasis on Social Realist figuration, exemplified by the murals of Thomas Hart Benton, his admiration for Mexican Muralists, such as Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, and his two-year scholarship to the American Artists School in 1937 where he studied with Social Realist artist Harry Gottlieb all separately introduced Lawrence to the evocative potential of narrative paintings conceived for the purpose of social commentary, an essential strategy employed in his historical series. In particular, Lawrence's affection for Orozco and his socially-charged painting was cemented in a more personal way. Recounting a meeting between himself and Orozco in 1940 at the Museum of Modern Art, Lawrence recalled that Orozco at first wouldn't talk to him, but instead requested that Lawrence go out and get him some cherries. Their subsequent conversation began with discussions about the cherries, which eventually led to Orozco looking at and praising Lawrence's work.

In 1940, Lawrence received a $1,500 fellowship from the Julius Rosenwald Fund to complete what would become one of his most acclaimed works, his 60-panel The Migration of the Negro series (1940-1941). The Migration of the Negro was as notable for its artistic achievements and the professional opportunities it afforded Lawrence. In addition to telling the story of the African-American "Great Migration," which his own parents had undertaken, the series enabled Lawrence to deepen his relationship with his future wife, Gwendolyn Knight. Lawrence had met Knight in Augusta Savage's art classes and while in Charles Alston's WPA workshops, and she was an artist assisting Lawrence with writing captions for The Migration series and preparing the gesso panels. Lawrence and Knight married in 1941.

At this stage, Lawrence was garnering mainstream art institutional support. He received a Guggenheim grant in 1946 to facilitate the completion of his War series, based on his experience as a war artist serving during the Second World War, and in 1944 he had a solo exhibition of his wartime works and The Migration of the Negro at MoMA - MoMA's first solo exhibition of an African-American artist.

Lawrence honed his compositional approach through the inspiration of Bauhaus émigré Josef Albers, who, in 1946, invited Lawrence to teach at Black Mountain College. The school was a refuge for the European avant-garde who fled the Second World War and became an integral creative incubator for the postwar generation of American Modernists like Robert Rauschenberg and Kenneth Noland. To combat the policy of Southern segregation still in effect during Lawrence's tenure at Black Mountain, Albers hired a private train car to bring Lawrence and his wife to and from the college, and the artist remained on campus for the duration of his time in North Carolina.

Following Albers' example, Lawrence embraced the emotional and symbolic potential of color juxtapositions and conceptualized pictorial space as if an architectural plane of interlocking shapes and lines. Though he generally rejected defining his work as a particular style, when pressed, Lawrence identified his work as "expressionist," referring to his desire to create artistic narratives which provoked strong emotional reactions in viewers. Art historian Patricia Hills has referred to Lawrence's style as "expressive cubism" and an "expressive flat collage cubist style."

Mature Period

In interviews, Lawrence always stressed the importance of personal experience to his creative efforts, and no work is more emblematic of this guiding principle than his 1950 Hospital series. Lawrence's career success arrived early: in 1935, at the age of eighteen, Lawrence began exhibiting his work, with a group exhibition at the Alston-Bannarn Studios on West 141st Street. By 1936, Lawrence had his first solo exhibition. The most prominent African-American artist in the 1930s through the 1950s, Lawrence was unsettled by the emotional and psychological burden of assuming such a symbolic status at such a young age. This pressure partly contributed to his mental breakdown in 1949, when Lawrence checked himself into a mental health treatment facility at Hillside Hospital in Queens. When he completed his hospitalization in August 1950, Lawrence created the Hospital series based on his year in treatment. With their honest, emotionally rich depictions of psychological illness and its treatment, these works were praised at the time of their 1950 exhibition at the Downtown Gallery as even more socially significant than his earlier historical series like The Migration of the Negro.

At midcentury and following his hospitalization, Lawrence's artistic style reached a new level of maturity, straddling the divide between abstraction and figuration with a new and bold geometricizing approach. He was no longer interested in repeating his past successes but in breaking new compositional and narrative ground. Though Lawrence's mature period coincided with the establishment of black artist groups in New York in the 1960s and though he would later exert considerable influence on contemporary black artists, Lawrence remained outside of these art circles due to his already-prominent stature in the art world. When Romare Bearden, Hale Woodruff, Norman Lewis, Emma Amos, and others formed the group Spiral in 1963, for instance, it was made clear to both Lawrence and Gwendolyn Lawrence that their help was not needed, as Spiral aspired to increase visibility for its own artists.

Lawrence was known as a gentle but tough artist, who, in the words of art historian Patricia Hills, "never swerved from his commitment to the struggle for a fair and just society," one which he aspired to realize through his art. The social charge of Lawrence's work is in evidence in his works of the 1960s, which responded to and critiqued police violence, racial unrest, and the backlash to school integration connected to the Civil Rights movement in America.

In 1962, Lawrence and Gwendolyn traveled to Nigeria, where his Migration series was being exhibited. While there, Lawrence lectured on African sculpture's role in the development of European and American avant-garde movements, particularly Cubism. The couple returned to Nigeria in 1964, but, upon their arrival, Lawrence and Gwendolyn were blacklisted, unable to secure housing, and under constant surveillance by the U.S. Government due to Lawrence's tangential affiliations with communist and communist-related groups back in America. Despite these circumstances, Lawrence's time in Africa was formative in his development as an artist and an educator, and Lawrence arranged for a cross-continental exchange of artistic knowledge, as Lawrence organized an exhibition of Black American artists in Senegal, and both Lawrence and Gwendolyn exhibited their works abroad.

Late Period

Lawrence's later career was marked by institutional validation, exemplified by his 1974 Whitney Museum of American Art retrospective which travelled to five other cities, and by Lawrence's position as a prominent art educator. Lawrence was on faculty at Pratt Institute from 1958 to 1970, taught at the New School for Social Research from 1966 to 1969, and in 1969, the University of Washington in Seattle offered him a full professorship, which he accepted. In 1963, Lawrence served on the advisory board for the founding of the Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C., and, in 1976, along with Romare Bearden, Willem de Kooning, and Bill Caldwell, Lawrence co-founded the Rainbow Art Foundation, an organization dedicated to helping young printmakers from minority backgrounds. Lawrence's educational mission extended until the end of his life: in 1999, he and Gwendolyn established the Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation to promote and support American art.

Lawrence also took on several large-scale mural commissions in his later career. In addition to Lawrence's exposure to mural work through his admiration for the Mexican Muralists, murals had been a part of Lawrence's artistic consciousness since his early days working with Charles Alston; Alston was, at one time, director of the WPA Harlem Mural Project, and completed murals for Harlem Hospital while Lawrence was his student. In 1955, Lawrence tied with artist Stuart Davis for a competition to design a mural for the United Nations building in New York. The project, though never completed due to lack of funds, was one of Lawrence's early forays into mural design. 1979, Lawrence completed his first mural commission, Games, for Kingdome Stadium in Seattle, Washington, and executed six additional murals over the next twelve years.

Lawrence was diagnosed with lung cancer in 1998. He passed away at home in June 2000 at age 82, leaving incomplete a series which focused on higher education and the university.

The Legacy of Jacob Lawrence

Lawrence is notable both for his artistic achievements as he is for being one of the first African-American artists to achieve widespread, mainstream acclaim. Lawrence was the first African-American artist to be represented by a New York commercial gallery, the Downtown Gallery in New York, where he exhibited from 1941 to 1953.

His work had a dramatic impact on succeeding artistic generations. Kerry James Marshall is one of the more prominent artists whose works riff on Lawrence's oeuvre both in his stylistic interplays between abstracted silhouette and figuration, and in his pointed commentary on black life. In addition, Lawrence's time in Nigeria as an educator and as an exhibitor influenced the artists of the Mbari art movement, including Uche Okeke, Demas Nwoko, Bruce Onobrakpeya, Yusul Grillos.

Influences and Connections

-

![José Clemente Orozco]() José Clemente Orozco

José Clemente Orozco -

![Josef Albers]() Josef Albers

Josef Albers -

![Käthe Kollwitz]() Käthe Kollwitz

Käthe Kollwitz ![Charles Alston]() Charles Alston

Charles Alston- Harry Gottlieb

- Alain Locke

- Lincoln Kirstein

- Jay Leyda

- Claude McKay

-

![Romare Bearden]() Romare Bearden

Romare Bearden -

![Hank Willis Thomas]() Hank Willis Thomas

Hank Willis Thomas -

![Kerry James Marshall]() Kerry James Marshall

Kerry James Marshall - Robert Colescott

- Alexis Gideon

- Barbara Earl Thomas

- Mary Randlett

Useful Resources on Jacob Lawrence

- Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series (2015)Our PickA complete catalogue of the artists' famed works in the Migration Series

- The Great Migration: An American StoryOur PickBy Jacob Lawrence / Comprehensive look at Lawrence's most famous collection of works

- Jacob Lawrence: Paintings, Drawings, and Murals (1935-1999): A Catalogue Raisonne (2001)By Peter T. Nesbett / A collection of prominent works by the artist

- Jacob Lawrence: American Painter (1986)A comprehensive survey of works by the artist

- Jacob Lawrence: The Complete Prints (1963-2000), A Catalogue Raisonne (2001)A closer look at the printed works by the artist

- Jacob Lawrence: Moving Forward, Paintings, 1936-1999 (2008)A collection of paintings by the artist featuring narratives of daily African American life

- Jacob Lawrence: The Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman Series of 1938-1940 (1991)Survey of works highlighting cultural icons, Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI