Summary of Harlem Renaissance Art

The term Harlem Renaissance refers to the prolific flowering of literary, visual, and musical arts within the African American community that emerged around 1920 in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City. The visual arts were one component of a rich cultural development, including many interdisciplinary collaborations, where artists worked closely with writers, publishers, playwrights, and musicians.

There was no single style that defined the Harlem Renaissance, rather artists found different ways to celebrate African American culture and identity. Often, they combined elements of African art with contemporary themes, creating a link that dignified and expanded the history of the African American experience, countering the derogatory caricatures that dominated popular culture.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The movement was originally referred to as the "New Negro" movement, referring to Alain LeRoy Locke's The New Negro (1925), an anthology which sought to inspire an African-American culture based in pride and self-dependence.

- Their careers hampered by racism in America, many first-generation members of the Harlem Renaissance worked abroad, many of them gathering in Paris before returning to New York to found and support opportunities for young African American artists. This created a second generation of locally-trained artists, who were rooted in Harlem and helped to shift the center of the art world to New York following WWII. Many of these second-generation artists became activists during the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s.

- As the Harlem Renaissance overlapped the Great Depression, many of its artists were employed under the government's Works Progress Administration (WPA) program, providing unprecedented support for African-American artists with prominent, large-scale commissions. They created public murals in buildings throughout the neighborhood, including Harlem Hospital and the New York Public Library (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture).

Artworks and Artists of Harlem Renaissance Art

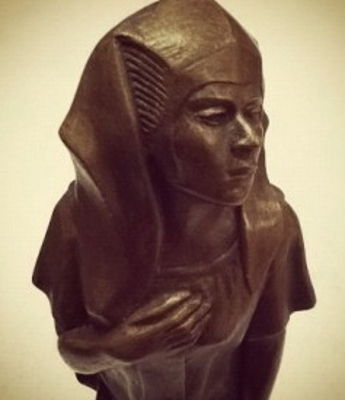

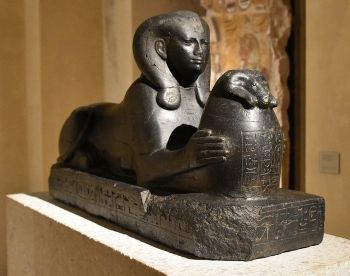

Ethiopia Awakening

This statue depicts a young black woman, dressed as an ancient Egyptian with the lower half of her body wrapped in mummy-like bandages. The woman's right palm rests on her breast, as if against her heart, while her left arm, flush against her body, ending with her fingers that extend outward in an expressive gesture. Softly turned toward her left, her closed eyes convey a depth of inner feeling.

The work has a two-pronged message: the title referring to Ethiopia, the only African nation had that retained its independence from Western powers (it would only later be occupied by Italy between 1936-1941), evokes African American self-determination, while the Nemes headdress worn by the woman (a symbol of power traditionally worn by the Egyptian pharaoh) suggests the dignity of African American women. The sculpture's elegant and flowing lines that move from the patterned mummy wrap to the headdress framing her face to create an idealized, but distinctly modern, effect. The contrast between the rigidity of the lower part of the figure's body, tightly encased, and the expressive movement of her upper body conveys a sense of awakening; this was Fuller's intent, as she explained, "Here was a group who had once made history and now after a long sleep was awaking, gradually unwinding the bandage of its mummied past and looking out on life again, expectant but unafraid and with at least a graceful gesture."

In 1921 W.E.B. Du Bois commissioned the artist to create a work that would symbolize African American contributions to American arts and industry to be included in the "Americans of Negro Lineage" section of the America's Making Exposition in New York City. Pioneering an expression of African-American pride, she connected modern trends in Western art with an awareness of the African and Egyptian influence on Western civilization. As historian Paul Von Blum later noted, the work was, "a response to Western societies that had promoted a caricature of Africa as a continent of barbaric tribes...Fuller's work helped her audiences to imagine an African history and culture that Western society had denied, even stolen. It was a powerful, compelling vision of black heritage."

Bronze - National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington DC

Alice Dunbar Nelson

Waring’s portrait presents American poet, journalist, essayist, and activist, Alice Dunbar Nelson, in all her finery. Dunbar Nelson, one of the first generation of free Blacks born in the South, was (like her friend Waring) university educated, and with her first husband, the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, an important symbolic figure within the Harlem Renaissance. Here Waring pictures her sitter bedecked in an elegant golden-yellow dress with large lacey sleeves, matched with black elbow-length demi-gloves, black high-heeled shoes, and a large hat adorned with decorative flowers. Waring’s portrait, which is reminiscent of Degas (Waring, who studied in Paris, was an admirer of the Impressionists), is typical of her portraits of successful Black individuals. Here, for instance, her delicate use of color and light works to underscore her subject’s dignified and self-confident personality.

Waring was unusual amongst artists associated with the Harlem Renaissance in that she was a recognized society painter (a genre traditionally associated with the White ruling classes). But it was in fact Waring’s (rare) painting of a Black working class woman, Anna Washington Derry (1925), that first brought her to the attention of the Harlem artists. Waring (a Philadelphian) exhibited Derry’s portrait at New York’s Harmon Foundation where it received the “First Award in Fine Art–Harmon Awards for Distinguished Achievement Among Negroes” in 1927. Having then arrived in New York, Waring - who was already a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and regularly contributed illustrations to the organization’s monthly magazine, The Crisis, and its children's publication, the Brownies' Book – came into contact with a number of artists, writers, and intellectuals associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Henry Ossawa Tanner introduced her to fellow artists, Palmer Hayden, Malvin Gray Johnson, Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, Augusta Savage, and Hale Woodruff; the poet, Langston Hughes; and the composer, Roland Hayes.

Waring’s approach was in sharp contrast to Harlem Renaissance contemporaries like Aaron Douglas, whose modernist outlook saw him favor a more simplified and abstract style. Waring even drew criticism in some quarters for being a “mere” society painter. But while her conservative style might not have appealed to the progressive tastes of modernists, her portraits brought an ostensibly apolitical dimension to the goals of the Harlem Renaissance and the early Civil Rights Movement in their unabashed celebration of the achievements of Black Americans. The art historian Amanda Lampel adds that Waring’s realist style was “in keeping with the types of artists who won the prestigious Harmon Foundation award, which sought to spotlight the up-and-coming Black artists of the Harlem Renaissance” and that most of the future award winners “painted more like Waring and less like Douglas”.

Oil on canvas - National Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C.

Gamin

This bust depicts an African American boy. Wearing a wrinkled shirt and bebop cap, he turns his head to his right with a thoughtful and reserved expression on his face. His somber gaze conveys an adult awareness of hardship and poverty, emphasized by the cropping away of his arms in a manner that suggests powerlessness and social constraint. It as if he wisely understands his situation but has little agency to remedy it, in the tradition of the titular gamin, or streetwise child. Some historians have suggested the bust depicts Ellis Ford, the artist's nephew, while others believe it was modeled on a street urchin, as the French title indicates.

The bust was met with acclaim, and, as a result, Savage was awarded a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship for study in Paris in 1929, where her work continued to be met with success. She exhibited both in the Salon d'Automne and at the Grand Palais in Paris. When she returned to Harlem in 1932, she founded the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts where she became one of the most influential teachers of the subsequent generation of Harlem Renaissance artists, including Jacob Lawrence. Although she was considered a leading Harlem Renaissance artist, poverty and misfortune led to her obscurity in the 1940s and the destruction of many of her artworks, though there has been a contemporary revival and rediscovery of her work.

Painted plaster - Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

Couple in Raccoon Coats

This iconic photograph depicts a young African American couple, both wearing full-length raccoon coats. The man in the driver's seat of his Cadillac roadster looks out at the photographer through the open door, while the woman, standing beside him, also turns toward the photographer. The car gleams with reflected light, particularly its chrome wheel on the front bumper, the frame of the open door, its diagonal beam drawing attention toward the man, and the roof of the car and its trunk. These highlighted forms create a kind of private space around him, conveying a sense of dignity and privacy that is reinforced by his expression, although shadowed, that suggests a self-confident reserve. The woman also radiates a sense of relaxed confidence in her pose and facial expression.

Van Der Zee opened his Harlem studio in 1916, which became successful during the World War I era, and in the 1920s he primarily photographed the rising middle class of Harlem, as well as the notable people of the Harlem Renaissance, including the political leader Marcus Garvey, the musician and dancer, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, and the writer Countee Cullen. Influenced by Pictorialism, Van Der Zee carefully arranged family portraits, community events, and funerals to create classical and idealized compositions, and perfected his images in the darkroom, using double exposures, composite images, and darkroom manipulations, "to make the camera take what I thought should be there" as he said.

Van Der Zee's contribution to the Harlem Renaissance was to create, as art historian Adrienne Child's wrote, "a virtual lexicon of New Negro identity as it developed during the Harlem Renaissance...The image with its hip and stylish African American couple personified the Jazz Age, and radically challenged popular culture's stereotypes and caricatures of African Americans." The raccoon coat was highly fashionable, associated with college-aged men; Van Der Zee deliberately connects his subjects with peers across racial barriers, countering derogatory stereotypes of urban blacks. The image was culturally influential, as the lifestyle it depicted became the aspiration of many young African Americans, and it launched a craze for raccoon coats among the denizens of Harlem's nightclub and music venues. His photographs fell into obscurity beginning in World War II, but were rediscovered when they were included in the Metropolitan Museum of Art's exhibition, "Harlem on My Mind" of 1969. Subsequently his photographs of Harlem funerals were published in The Harlem Book of the Dead (1978) with a foreword by the Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison.

Gelatin silver print - Detroit Institute of Art, Detroit, Michigan

Black Belt

This boldly colored painting depicts a busy street at night in the Black Belt, the popular name for the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago which was noted for its jazz and cabaret clubs. The scene hums with activity as electric lights and signs create a kind of syncopated rhythm of stage-like illumination, transforming the street into a kind of public theatre. The various figures represent a gathering of types: the hip couple on the right, the policeman on the left trying to help an older man pick up his newspapers. The women wear low cut and tightly fitting dresses in saturated colors, and the young men have the fashionable hats. The exception is a heavyset man, his white sleeves rolled up as if for work. Bent over with his gaze down, his shoulders rounded as if with exhaustion, the man's presence is disconcerting. Some scholars have suggested that this figure, which appears in several of Motley's paintings, is a kind of artistic alter ego, conveying the toll of racism with his stolid and bent appearance. Juxtaposed against the man's blocky and dark figure the colors of the women's dresses take on an air of artificiality, as if everyone were out trying to have a good time, while at the same time fending off the despair embodied in the man.

Influenced by the artist George Bellows and the works of the old masters, including Peter Paul Rubens, Rembrandt van Rijn and Frans Hals, Motley's paintings were noted for their physicality, his rendering of the variations of skin tone, and his un-idealized depictions of black life that sometimes evoked stereotypes in order to subvert them. Here, the stereotype of black nightlife as a wild celebration that drew many white people to areas like the Black Belt is subverted by the painting's disquiet, as the isolated figures stand about or just make their way through the crowd, making an effort to find connection. Of African, Native American, and European ancestry, Motley's "mixed racial heritage," as art critic Edward M. Gómez, wrote, "estranged him from both the white and black communities. In a single work he could go from keen observation and telling detail to caricature and exaggeration, provoking a disquieting self-consciousness in the viewer." As a result the Chicago artist remained somewhat at the periphery of the Harlem Renaissance, though as Gómez notes, his work "anticipates the use of stereotypes and exaggeration by Ellen Gallagher and Kara Walker."

Oil on canvas - Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Virginia

Let My People Go

This work depicts the Biblical leader Moses, as he kneels with the pyramids of Giza behind him. This is the moment when God calls him to lead the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt. At upper left, three yellow concentric rings represent both the sun and the trinity, from which streams a diagonal beam of light that, representing God's command, intersects the canvas and illuminates Moses's silhouetted form. Lavender waves crest on the left over the dark silhouettes of the Pharaoh and his army, alluding to the subsequent pursuit of the fleeing Israelites and the drowning of the army in the Red Sea. Douglas's color palette unifies the image, as the lavender that depicts Moses is echoed in the saving waves and the divine storm on the upper right, while the yellow of God's illumination contrasts with the black figures, horses, and weapons of the Pharaoh's army.

Part of an eight painting series, Douglas based the paintings on his earlier illustrations for James Weldon Johnson's God's Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927). His depiction expressed a longstanding African American religious tradition that connected the oppression of the Israelites to the oppression of African Americans, as black spirituals referring to Biblical stories were one of the few ways that slaves could safely express their longing for freedom. As he said, "I tried to keep my forms very stark and geometric with my main emphasis on the human body. I tried to portray everything...simplified and abstract as . . . in the spirituals. In fact I used the starkness of the old spirituals as my model - and at the same time I tried to make my painting modern."

His modernist idiom included Art Deco arabesques, as shown here in the waves and clouds, to pioneer a kind of jazz painting that drew on visual rhythms of line and color. Douglas's use of silhouettes evoked Egyptian art while allowing him to create idealized portrayals of African Americans that could also suggest a universal form. It was a 'human shape' that could not be reduced to caricature. Second-generation Harlem Renaissance artists, including Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden, employed silhouettes as have contemporary artists such as Kara Walker, Lorna Simpson, and Laylah Ali.

Oil on Masonite - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Les Fétiches

This depiction of an African mask gazes forward with beveled oval eyes accentuated by carved eyebrows that create flowing contours down to the chin, creating a geometric portrait that suggests a strong human presence. The apex of the triangular nose is formed by contrasting light and dark tones that flow upward into the forehead, creating a vertical movement that is echoed in green and red feathery plumes. The pattern continues on the periphery, creates a sense of swirling movement. Other masks emerge into this spotlight: a striped wooden mask juts into the pictorial plane, a dark mask with white banded slit-like eyes facing forward, a curving biomorphic mask with its jaws toward the chin of the central figure, and a horned mask in the lower right. At center right, a red African fetish statue stands erect, as if it were evoking this gathering of masks that evoke an assembly or a ritual dance. The masks themselves are copied from different African tribes, including the Songye Kifwebe and Guru Dan.

Jones grew up in Boston and studied art in France, where she turned to depicting African themes and subjects. She credited Grace Ripley, a costume designer and lifelong friend, with influencing this work and her interest in masks. In Paris, Jones studied African art, including masks at the Musée de l'Homme. Primitivism among the early 20th-century modernists had incorporated the aesthetic of these non-Western sources, however Jones explored more specific and cultural dimensions of the mask. When her teachers questioned her African themes, she replied, "if masters like Matisse and Picasso could use them, don't you think I should?" This painting was a seminal work in the transition of Négritude, a French literary movement, into the visual arts. Art historian Holland Carter has called it "an emblem of black American self-identity." Returning to the United States, Jones later taught at Howard University where she influenced subsequent generations of African American artists including Alma Thomas, Elizabeth Catlett, and David Driskell.

Oil on linen - Smithsonian American Art Museum

The Migration of the Negro, Panel 3

To create the sixty panels that made up his Migration of the Negro series, Lawrence conducted extensive research, combing through library archives, historical documents, and eyewitness accounts. Wanting the panels to work as a single story, he worked on them simultaneously, as if they were film storyboards. Each panel had a caption, as this one read: "From every Southern town migrants left by the hundreds to travel north," and, taken together, the works conveyed a powerful narrative. Jay Layda, an assistant film curator at the Museum of Modern Art who recognized the cinematic quality of Lawrence's work, lobbied for the artist to receive the Julius Rosenwald Fund fellowship to finance the Migration series.

This panel depicts a group of African Americans carrying their possessions, formed into a pyramidal shape that emphasizes their collective strength and purpose during the Great Migration north. Some of the figures have their heads bowed, conveying exhaustion and depression. The artist employs elemental forms, flat planes of color, whose lines creates both a horizontal movement pressing forward and vertical movement toward the blue sky with its six black crows spread out across the horizon, the curve of a barren hill. As a result, both the group's struggle forward and their struggle to rise and overcome are conveyed.

Lawrence called this combination of broad planes of bold color and flat linear design, "dynamic cubism," though it was not so much influenced by European Cubism, but by his own childhood and the colors and shapes of Harlem. The leading artist of the second generation of Harlem Renaissance artists, he studied at the Harlem Art Workshop with Charles Alston and then the Harlem Community Art Center with the sculptor Augusta Savage, making him "first major artist of the 20th-century who was technically trained and artistically educated within the art community in Harlem," as art historian Leslie King-Hammond has noted.

The series was immediately successful and was featured in Fortune magazine . Both the Museum of Modern Art and The Phillips Collection added the works to their collection, with MOMA taking the even numbered panels, and The Phillips, the odd numbered works. Lawrence's work has continued to be influential, as seen in a legacy of artists that include Kerry James Marshall, Faith Ringgold, Robert Colescott, Hank Willis Thomas, and Alexis Gideon.

Tempera on gesso on composition board - The Phillips Collection, Washington DC

Blind Singer

This screenprint uses a cutout effect and bold planes of color to depict two Harlem musicians; the woman playing a guitar, while the blind singer of the title stands beside her, eyes closed and mouth open in song. Rendered in a primitive style that is influenced by folk art, children's art, and African art, they become emblems of the many street musicians in Harlem. The angular treatment of the figures creates a rhythmic energy, almost as if the song could be heard in their jaunty forms. Their strong contours and bold colors command the viewer's attention. The absence of any background focuses the work on the two figures, dignifying its titular subject who would have been marginalized as a black man, a disabled man, and a street performer.

Johnson worked in an expressionistic style, but in 1938, he and his wife fled pre-World War II Europe and returned to Harlem. While teaching children at the Harlem Community Arts Center under the Works Progress Administration, his work changed radically as he turned to depictions of African American life and he adopted a more primitivizing style. He turned to screenprinting and pochoir, the use of fine stencils to create images, as he created small works printed on various found papers or completed by hand. He found the process of printmaking to have an elemental simplicity, saying "My aim is to express in a natural way what I feel, what is in me, both rhythmically and spiritually."

Screenprint with tempera additions - The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

Boxer

This work depicts "Kid Chocolate," a Cuban boxer and the Junior Lightweight Champion from 1931-1933, known for his New York bohemian lifestyle. Shown nude, except for the boxing gloves on his hands, his muscular but lean body is accentuated. With his head tucked down, his right arm is raised as if to parry a blow as he strides forward, balanced on the balls of his feet; the effect is the impression of lyrical movement and strength. The artist formed the work from memory, noting how the boxer "moved like a ballet dancer."

Barthé grew up in Mississippi and later studied at the Art Institute of Chicago where his teacher, the German artist Charles Schroeder, emphasized modeling in clay, a practice that turned the young artist toward sculpture. He moved to Harlem in 1930, where he quickly became famous when his Blackberry Woman (1930) was included in the Whitney Museum of American Art's Annual show and subsequently purchased by the museum. In 1931 he moved his studio to Greenwich Village to make more connections with collectors and patrons; the move also transformed his art as he mingled with the bohemian circles of musicians, actors, athletes and dancers, often employing them as models.

Barthé's unique contribution to African American portrayal was his focus on human movement, as he employed stylistic distortions to emphasize movement as a reflection of inner identity. As said "All my life I have been interested in trying to capture the spiritual quality I see and feel in people, and I feel that the human figure as God made it, is the best means of expressing this spirit in man."

Bronze - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, New York

Can Fire in the Park

This vividly colored painting, its color palette and thick paint influenced by the Fauves, creates an empathetic scene of homeless people gathered around a trash can fire in a city park as they try to keep warm. The artist employs a thick impasto of paint to create swirling waves of blue shadow and yellow light, while the fire hydrant on the left, the street sign on the right, and a manhole cover in the lower right are depicted as simple geometric forms that become emblematic signs of city life. Depicted as dark shapes, with a hat brim or a sleeve lit up by the warming flames, the body language of each figure conveys individual feeling while the indistinct features evokes the social invisibility of the poor and homeless. A hint of narrative piques the viewer's interest: small details of dress and posture invite us to ponder their individual stories.

Born in Tennessee, Delany studied art in Boston before moving to Harlem in 1929, and then Greenwich Village, where he became known for his portraits in pastels. In the 1940s he began employing thick impasto, like what we see here, to portray urban and interior scenes. This technique introduced an innovative materiality and emphasis on process into Harlem Renaissance subject matter. In 1953, he moved to Paris where his work became nonrepresentational and associated with Abstract Expressionism, though he never identified with the movement. While he played a vital role in artistic and literary circles, his life was marked by poverty, mental illness, and the struggle to find a place for himself as an African American artist and a gay man. As the noted writer James Baldwin, who called Delaney "his spiritual father," wrote after the artist's death, "He has been starving and working all of his life - in Tennessee, in Boston, in New York, and now in Paris. He has been menaced more than any other man I know by his social circumstances and also by all the emotional and psychological stratagems he has been forced to use to survive; and, more than any other man I know, he has transcended both the inner and outer darkness." Though praised as a great but neglected artist, Delaney's work fell into obscurity until exhibitions in the late 1980s and early 1990s revived interest in his oeuvre. More recently, a 2016 retrospective of his work that opened on the Paris campus of Columbia University before touring the United States has brought new awareness to his importance as a pioneering African-American artist in nonrepresentational art.

Oil on canvas - Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

Beginnings of Harlem Renaissance Art

African American artists of the 19th century

For artists of the Harlem Renaissance looking for professional African-American role models, only Henry Ossawa Tanner and Edmonia Lewis had gained international fame and success. Yet, faced with racial discrimination and career limitations in America, both artists spent most of their lives in Europe (Tanner in Paris and Lewis in Rome) where they found a more tolerant cultural and artistic environment in the decades following the American Civil War.

Of African American and Native American heritage, Mary Edmonia Lewis was born in upstate New York. In 1864, she moved to Boston to study sculpture but her race and gender made it difficult to find an instructor. She eventually studied with Edward August Brackett, a sculptor who specialized in portrait busts of the leading abolitionists. Lewis focused on themes of emancipation, including a bust of Union Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, a noted abolitionist who led the first all-black regiment in the Civil War. Although her work received acclaim and was widely copied, she continued to face discrimination; looking for more hospitable working conditions, Lewis moved to Rome in 1866 where she became a leading sculptor in the Neoclassical style. As she later explained, "The land of liberty had no room for a colored sculptor."

Lewis's most celebrated sculpture was her monumental The Death of Cleopatra (1876), which was exhibited in the Centennial Exposition of 1876 in Philadelphia to great acclaim. Although her classical style was not directly influential to artists of the Harlem Renaissance, Lewis provided an inspirational model for how African American women artists might achieve success by combining contemporary trends and African themes.

Henry Ossawa Tanner studied with the painter Thomas Eakins, alongside Robert Henri at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In 1891, he moved to Paris to study art at the Académie Julian, seeking an environment where he could work without racism. In France, he began painting landscapes and genre scenes, influenced by the Realists Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet. He did return to the United States for a few years, during which time he turned to African American subjects, such as his The Banjo Lesson (1893) and The Thankful Poor (1894). He joined the National Citizens Right Association (a predecessor to the NAACP) and gave a lecture on "The American Negro in Art" at the World's Congress on Africa, held at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893). Returning to France, his subsequent work was devoted to religious subjects. Tanner became an important supporter of young Harlem Renaissance artists, opening his Paris studio to artists including Hale Woodruff, William H. Johnson, and Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller.

The Great Migration

The Great Migration began around 1910, as large numbers of African Americans moved from the rural South to Northern and Midwestern cities, escaping the widespread discrimination and violence of the segregated South and seeking opportunities for work. The combination of Jim Crow laws that rigidly enforced segregation and restricted the civil rights of black Americans and Northern companies that offered incentives to recruit black workers (a drive which intensified during World War I when war mobilization diminished the industrial work force) encouraged thousands of African Americans to migrate.

The Red Summer

As African Americans moved to Northern cities and filled industrial and railway jobs, racial tensions escalated. In 1919, white mobs in more than three-dozen American cities instigated riots, attacking and lynching African Americans, destroying their neighborhoods and businesses. Called "The Red Summer," the violence contributed to the development of the Harlem Renaissance, as African American communities organized nonviolent protests. As the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) (founded by W.E.B. Du Bois in 1907) protested to President Woodrow Wilson, the group grew in membership and visibility. Claude McKay's poem "If We Must Die" (1919) expressed the passion for equality and respect that became central themes of the Harlem Renaissance: "If we must die, O let us nobly die.../Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!"

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller

An early pioneer in both the African American subjects and Egyptian-inspired style that dominated the early years of the Harlem Renaissance was the sculptor Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller. Born and raised in Philadelphia, she studied sculpture at the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art, but it was her time in Paris that most influenced her work. For many Harlem Renaissance artists, Paris became a mecca, where they found a more welcoming society and could achieve artistic success. In 1899, while studying sculpture at the Académie Colarossi and drawing at the École des Beaux-Arts, she met the African American thinker and activist W.E.B. Du Bois, Henry Ossawa Tanner, and the famous Auguste Rodin. Du Bois, who became a lifelong friend, encouraged her to explore African and African American subjects, while Rodin, her mentor, influenced her to develop an approach to realism that conveyed the inner feeling of the subject.

In 1919, Fuller's Mary Turner: A Silent Protest Against Mob Violence depicted a nineteen-year old pregnant African-American woman who had been lynched in Georgia in 1918 after protesting the lynching of her husband the day before. By portraying Turner as an idealized and dignified presence above the disembodied faces of the mob, the work was itself a radical protest. And, Fuller's most influential sculpture was her Ethiopia Awakening (1921) commissioned for the America's Making Exposition in New York City. The work used the aesthetic and cultural traditions of Egypt to celebrate African-American identity, a combination that became a dominant motif in Harlem Renaissance art.

Fuller explained her use of Egyptian motifs by declaring the reign of the Negro Kushite kings (712-664 BCE) as the most brilliant era of Egyptian history. This claim was supported by reports on the archeological discovery of Meroe, the Kushite capital city in the Sudan, which had been published by Crisis, the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, in 1911. Her friendship with Du Bois also influenced her style; he was an ardent proponent of Pan Africanism, an international movement that connected African and African-American pride to its historical sources in Africa, promoting the discoveries of Egyptian and Nubian art as artistic and cultural models.

Alain LeRoy Locke and The New Negro (1925)

Dubbed "the Dean" of the Harlem Renaissance, Alain LeRoy Locke provided the basis for the intellectual architecture of the movement. A noted philosopher, sociologist, writer, educator, critic and patron of the arts, his essay "Harlem, Mecca of the New Negro" in included in a 1925 issue of Survey Graphic that introduced Harlem and its culture to a general audience. He expanded these ideas in The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925), an anthology that included his influential essays, "The New Negro", "Negro Youth Speaks", "The Negro Spirituals", and "The Legacy of Ancestral Arts."

The central drive of the Harlem Renaissance - the development and promotion of a distinctly African American culture - was inspired by Alain LeRoy Locke's The New Negro (1925), which called for "a new dynamic phase ... of renewed self-respect and self-dependence" within the community. Locke's work expressed and refined ideas that that had been fermenting in the African American intellectual community since the 1890s, led by the sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois, the writer Booker T. Washington, and social activist Hubert H. Harrison. Building upon works, including Washington's A New Negro for a New Century (1900), Locke's anthology became known as "the first national book" of African American experience and identity. In it, he argued for self-confidence, social awareness, and an emphasis on black equality. The anthology also included poetry and fiction that reflected similar themes, by the leading writers of the Harlem Renaissance, including Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Jean Toomer, and Claude McKay.

Locke contrasted the "old Negro," beaten down by legacies of slavery and the Jim Crow era, with the "new Negro," who could start over in northern cities; he saw new possibilities for challenging and changing old stereotypes, as well as opportunities to overcome the internalized effects of oppression. He emphasized "the necessity for fuller, truer self-expression" to achieve spiritual emancipation, and his ideas influenced the jazz musician Duke Ellington, the writers Langston Hughes and Claude McKay, the sculptor Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, and the painter Aaron Douglas. The Harlem Renaissance was distinguished for its rich and diverse, interdisciplinary collaborations, inspired by Locke's view that "the moral function of art...is to remove prejudice, do away with the scales that keep eye from seeing, tear away the veils due to wont and custom, perfect the power to perceive." This sentiment became the de facto manifesto of the movement.

Aaron Douglas

Aaron Douglas became a leader within the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s. Raised in Kansas, he moved to New York City where he studied with the German artist Winold Reiss, whose paintings and graphics reflected the Art Deco style. Reiss was also an advocate and supporter of the writings of Alain Locke; he and Douglas illustrated the first edition of Locke's New Negro: An Interpretation (1925).

Working with Reiss, Douglas developed a distinctive style that combined influences from African American folk art and African art with Art Deco stylization. In projects such as his illustrations for James Weldon Johnson's God Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927), Douglas's iconography linked Christian subjects and black subject matter to convey racial pride and spiritual longing in an influential modernist style. He combined African subjects with an American modernist look that brought together a deep tradition and abstract energy. His work, along with his legacy of teaching, made him an influential figure for generations of African-American painters.

Langston Hughes and Fire!!

The leading poet of the movement, Langston Hughes, pioneered a new style based upon jazz music's rhythms and improvisatory technique. He focused on working class African American life in works such as his poem, "The Negro Speaks of Rivers" (1921), explaining "my seeking has been to explain and illuminate the Negro condition in America and obliquely that of all human kind," His work became widely influential for its appeal to racial pride and identity. He also argued for racial unity in the manifesto "The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain" (1926), which criticized divisions within the black community itself that were based upon social class and skin color.

In 1926 Aaron Douglas, Langston Hughes, Wallace Thurman, and Countee McCullen cofounded Fire!!, the first Harlem Renaissance literary magazine. Although the magazine was plagued by financial difficulties and produced only one issue, it was widely influential. It challenged what Hughes called, "the old, dead conventional Negro-white ideas of the past" and took on controversial issues within African American communities including gay relationships, interracial relationships, and color prejudices. The literary arm of the Harlem Renaissance influenced subsequent generations of writers, including James Baldwin, who grew up in Harlem and became known for his profound analysis of racial, class, and gender in Notes of a Native Son (1955) and The Fire Next Time (1963)

The 1930's: The Schools of Arts and Crafts and The Harlem Community Art Center

During the Great Depression economic hardships forced many African American artists living in Paris to return home. In the decade that followed, artists founded schools, community centers, and art collectives in Harlem as they sought to create their own venues for opportunity. In 1932, Augusta Savage founded the Savage School of Arts and Crafts and became an influential teacher to a second generation of Harlem artists, including Norman Lewis, Romare Bearden, and Jacob Lawrence. In 1935, she cofounded the Harlem Artists Guild in order to train young artists, encourage community arts involvement and education, and create more opportunity for black artists. The Guild also advocated that the Federal Arts Project, a branch of the Works Progress Administration, needed to recruit more African Americans. In 1937, The Harlem Artists Guild succeeded in opening the Harlem Community Art Center, funded by the WPA; Savage was appointed as its first director. It remained a vibrant hub of the arts until World War II, when a lack of funding closed its doors.

Harlem Renaissance Art: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Music

Throughout the 1920s, the Harlem Renaissance developed alongside the "Jazz Age" as noted performers including Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, and Cab Calloway played in Harlem nightclubs. While widely popular, jazz was initially met with some resistance from the African-American middle class who associated it with lower-class entertainment. The development of the Harlem Stride in the early 1920s helped bridge this class gap, as the piano, an instrument associated with the upper class, was added to the Southern brass band. At the time, white audiences flocked to Harlem venues, drawn by the lively nightlife. The Cotton Club from 1923 to 1935 was the most famous nightclub, and, though it was a whites-only establishment, most of the era's popular African American vocalists, dancers, entertainers, and musicians performed there.

The blues, performed by Ma Rainey ("The Mother of the Blues"), Bessie Smith, Mamie Smith, and later Billie Holiday, were equally interwoven with the Harlem Renaissance. Drawing upon the tradition of spirituals, the blues expressed personal woes, lost love, hard times, and the troubles within the community, but some songs were also bawdy, expressing the era's more open sexual moirés.

In addition, a variety of musical performers at the time created new fusion styles, innovatively exploring new techniques, like "scat," a vocal rendition based upon jazz improvisation. White composers like George Gershwin were also drawn to African-American music and began to incorporate it into their own work. Gershwin's Porgy and Bess (1935), a work he called "a folk opera," told the tragic story of an African American couple.

Jazz also influenced the visual arts. Aaron Douglas wanted his painting to convey the abstract quality he associated with Negro spirituals while also having a kind of jazz-like visual rhythm. The Chicago artist Archibald J. Motley (although he was not really part of the New York movement) often portrayed scenes of African American nightlife in what he called a "jazz syncopated" style, using bold colors and juxtapositions.

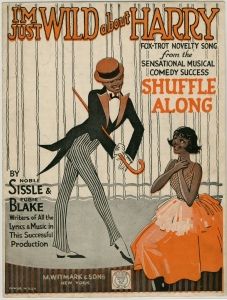

Theatre

The musical comedy Shuffle Along (1921) employed an African-American cast that introduced Paul Robeson and Josephine Baker. The show was written by four vaudeville stars, the comedians Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles and the jazz singers Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle. Robeson went on to become the leading African-American actor of the Harlem Renaissance while Baker became an international celebrity, known for her dazzling and provocative performances. Shuffle Along's jazz music, memorable hits, and chorus line of professional African American dancers, made it an instant hit, and influenced a wide range of artists, including Fanny Brice, Al Jolson, Langston Hughes and George Gershwin. The show also played a role in the desegregation of theatres in the 1920s.

In the following decade, many African-American musicals opened on Broadway. Importantly, Blackbirds of 1928, featuring the singer and performer Adelaide Hall and the famed dancer Bill "Bojangles" Robinson developed out of a club floorshow to become hit on Broadway and at the Moulin Rouge in Paris. Also, several all-black theatrical groups formed, including the Krigwa Players Little Theatre Group, cofounded by Du Bois and Regina Anderson in 1925 to serve as a political theatre to advance African American playwrights. In 1928, the Krigwa Players evolved into the Harlem Experimental Theatre.

Photography

The noted photographers of the Harlem Renaissance included James Van Der Zee, James Latimer Allen, and Roy DeCarava, each of whom captured the realities of Harlem life within the context of the New Negro movement. Both Van Der Zee and Allen were known for their studio portraits, though they focused on different groups; Van Der Zee took photographs of the younger, hip community and the middle class, while Allen captured the educated upper class. DeCarava started his career as a painter and printmaker for WPA posters in the 1930s, before turning to photography in the 1940s. He became renowned for his images of everyday black life in Harlem, finding in photography a way of refuting "black people...not being portrayed in a serious and artistic way."

Film

William D. Foster and Noble Johnson were early leaders of filmmaking; Foster, founded the Foster Photoplay Company in Chicago in 1910, becoming the first African American to start a film production company. He became the first African American director with his The Railroad Porter (1913). Noble Johnson founded the Lincoln Motion Picture Company in 1915, moving the company to Los Angeles the following year. These early filmmakers made black films staring black actors; they created a genre known as "race films." As movie houses were segregated, they were shown through a distribution system called Midnight Rambles, referencing the late night showings that were arranged for black audiences. Many of the films, like the Lincoln Company's The Realization of a Negro's Ambition (1916), were socially conscious and attempted to address negative stereotypes.

Oscar Micheaux was the Harlem Renaissance's leading African-American film producer and director, making more than forty films. His first production was The Homesteader (1919), based upon his own experience which he had previously fictionalized in the popular novel The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Homesteader (1913). Micheaux's films often emphasized African American success in realizing their own potential in areas that had previously closed to them. His second silent film Within Our Gates (1920) countered many of the racial stereotypes that had been reinforced in D.W. Griffith's infamous Birth of a Nation (1919). His films launched the careers of leading African American actors, including Ethel Morris who was dubbed "the black Jean Harlow" and whose glamorous image influenced popular culture.

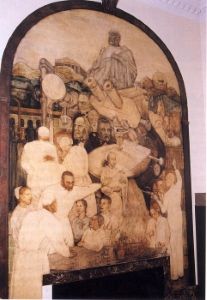

Murals

In the 1930s, murals became a dominant art form for Harlem Renaissance artists who worked for the Works Progress Administration (a New Deal program of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's presidency, designed to counteract the effects of the Great Depression by providing work for artists). Local murals portrayed both contemporary and historical African American life and created connection with African-American communities. Pioneering the form, Aaron Douglas's Aspects of Negro Life (1934) was a four panel series created for the New York Public Library's 135th Street branch that depicted African American life from slavery to the modern era. Mural projects also created unexpected connections between African-American artists and rural, primarily white, communities in the Midwest, such as Archibald Motley's Stagecoach and Mail (1937) an Illinois Federal Arts Project created for a small-town post office in Illinois.

Other murals informed and evoked forgotten moments of African-American history, such as Hale Woodruff's The Mutiny on the Amistad (1939). For example, in a series of three monumental paintings created for the Talladega College library in Alabama, Woodruff depicted the historical account of the Amistad. When the college commissioned the works in 1938, few had ever heard of the event, including the artist who had to engage in extensive research to create the work. Modern day art critic Roberta Smith wrote that the works "teach history by making it visually riveting."

Other murals connected African traditions to modern life, as Charles Alston's pair of murals: Magic in Medicine (1940), which depicted traditional African healing methods, and the contemporary practices of Modern Medicine (1940). In 1937, Alston was the first African American to assume a leadership role in the Federal Arts Project, but these panels created for the Harlem Hospital, were controversial and therefore not installed until 1940.

Illustrations

Many notable artists also created work for book illustrations, children's literature, brochures, advertisements, and posters. Often, their work blurred the categories of illustration and high art, such as Aaron Douglas's illustrations for James Weldon Johnson's God Trombones: for Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927), which became the basis for his later masterworks like Let My People Go (c. 1935-39). Collaborations between the leading women artists of the Harlem Renaissance, such as Loïs Mailou Jones, who illustrated Gertrude P. McBrown's poem "Fire-Flies"(1929) for the Saturday Evening Quill, brought greater visibility to African American women. Female illustrators, such as Elanor Paul and Gwendolyn Bennett, also challenged gender stereotypes by portraying African American women as powerfully capable of taking on roles in all aspects of modern economic life. Illustration also launched the careers of second generation artists like Beauford Delaney, who worked in the 1930s creating images for the poster division of the WPA before becoming a painter.

Later Developments - After Harlem Renaissance Art

The Harlem Renaissance came to an end in the early 1940s with World War II. Yet, even without its geographic center, a second generation of Harlem Renaissance artists, like Jacob Lawrence and Charles Alston, continued working in the following decades. Others, like Romare Bearden, explored new subject matter and styles.

The Harlem Renaissance influenced Négritude, a literary and cultural movement that began in the 1930s and was led by Aimé Césaire, Leopoldl Senghor, and Leon Damas. This group of French speaking authors from French colonies in Africa and the Caribbean had a long lasting influence in subsequent decades, including upon the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre.

A number of Harlem Renaissance artists, including Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Loïs Mailou Jones, Augusta Savage, Charles Alston, and Aaron Douglas were noted teachers, influencing subsequent generations. Howard University became one noted center for African American art under Jones's instruction of later artists including Alma Thomas, Elizabeth Catlett, and David Driskell.

Jacob Lawrence's work influenced a number of later artists, including Kerry James Marshall (whose own work influenced the Mbari art movement in Kenya), and Faith Ringgold (whose work played an important role in the 1970s Feminist art movement), as well as Robert Colescott, Hank Willis Thomas, and Alexis Gideon.

Scholars have argued that Aaron Douglas's use of silhouettes, which influenced Jacob Lawrence, William H. Johnson, and Romare Bearden, were a uniquely African-American formal device. Contemporary 21st-century artists, including Kara Walker, Laylah Ali, Lorna Simpson, Michael Ray Charles, and Kerry James Marshall have extensively employed the silhouette to critique racial attitudes. Carrie Mae Weems has also cited the Harlem Renaissance, particularly the work of Langston Hughes, as an influence upon her work.

Useful Resources on Harlem Renaissance Art

-

![Harlem Renaissance: Music, Poets, Entertainment, Politics, and Culture (2001)]() 80k viewsHarlem Renaissance: Music, Poets, Entertainment, Politics, and Culture (2001)The Film Archives

80k viewsHarlem Renaissance: Music, Poets, Entertainment, Politics, and Culture (2001)The Film Archives -

![Harlem Renaissance]() 39k viewsHarlem RenaissanceSojournals

39k viewsHarlem RenaissanceSojournals -

![Study of Negro Artists]() 2k viewsStudy of Negro ArtistsOur PickNational Archives Video Collection

2k viewsStudy of Negro ArtistsOur PickNational Archives Video Collection

-

![Jacob Lawrence and the Making of the Migration Series]() 36k viewsJacob Lawrence and the Making of the Migration SeriesPhillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

36k viewsJacob Lawrence and the Making of the Migration SeriesPhillips Collection, Washington, D.C. -

![Richmond Barthé: African-American sculptor (1901-1989)]() 12k viewsRichmond Barthé: African-American sculptor (1901-1989)AfricanAmericanArt

12k viewsRichmond Barthé: African-American sculptor (1901-1989)AfricanAmericanArt -

![Aaron Douglas: African-American painter (1898-1979)]() 23k viewsAaron Douglas: African-American painter (1898-1979)AfricanAmericanArt

23k viewsAaron Douglas: African-American painter (1898-1979)AfricanAmericanArt -

![Loïs Mailou Jones - Good Morning America Interview]() 9k viewsLoïs Mailou Jones - Good Morning America InterviewOur Pick

9k viewsLoïs Mailou Jones - Good Morning America InterviewOur Pick -

![Loïs Mailou Jones paved a path for black artists who had been shut out of the world of fine art]() 0 viewsLoïs Mailou Jones paved a path for black artists who had been shut out of the world of fine artTimeline

0 viewsLoïs Mailou Jones paved a path for black artists who had been shut out of the world of fine artTimeline -

![Augusta Savage: The Harp]() 10k viewsAugusta Savage: The HarpChiTownView

10k viewsAugusta Savage: The HarpChiTownView - Two interviews with Jacob LawrenceOur PickMuseum of Modern Art, New York, New York

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI