Summary of Neoclassicism

New classics of the highest rank! This was the rallying cry of populations immersed in the 18th century Age of Enlightenment who wanted their artwork and architecture to mirror, and carry the same set of standards, as the idealized works of the Greeks and Romans. In conjunction with the exciting archaeological rediscoveries of Pompeii and Herculaneum in Rome, Neoclassicism arose as artists and architects infused their work with past Greco-Roman ideals. A return to the study of science, history, mathematics, and anatomical correctness abounded, replacing the Rococo vanity culture and court-painting climate that preceded.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Neoclassical art arose in opposition to the overly decorative and gaudy styles of Rococo and Baroque that were infusing society with a vanity art culture based on personal conceits and whimsy. It brought about a general revival in classical thought that mirrored what was going on in political and social arenas of the time, leading to the French Revolution.

- The primary Neoclassicist belief was that art should express the ideal virtues in life and could improve the viewer by imparting a moralizing message. It had the power to civilize, reform, and transform society, as society itself was being transformed by new approaches to government and the rising forces of the Industrial Revolution, driven by scientific discovery and invention.

- Neoclassical architecture was based on the principles of simplicity, symmetry, and mathematics, which were seen as virtues of the arts in Ancient Greece and Rome. It also evolved the more recent influences of the equally antiquity-informed 16th century Renaissance Classicism.

- Neoclassicism's rise was in large part due to the popularity of the Grand Tour, in which art students and the general aristocracy were given access to recently unearthed ruins in Italy, and as a result became enamored with the aesthetics and philosophies of ancient art.

Artworks and Artists of Neoclassicism

Death of General Wolfe

This painting shows the death of Major-General James Wolfe on the Plains of Abraham at the Battle of Quebec in 1759 during the Seven Years' War, known in the United States as the French and Indian War. Wolfe was killed by musket fire in the brief battle as he led the British forces to victory, setting in motion the conquest of Canada from the French. We see him lying on the battlefield as he is surrounded and comforted by a group of officers. His figure, creating the base of a pyramidal grouping that rises to the partially furled flag above, and his pale face are lit up with a Christ-like illumination, making him the visual and emotional center of the work. To the left a group of officers stand in attendance, conveying a distress reminiscent of depictions of the mourning of Christ. In the left foreground, a single Indigenous man sits, his chin in his hand, as if deep in thought. Two more officers on the right frame the scene, while in the background the opposing forces mill, and black smoke from the battlefield and storm clouds converge around the intersecting diagonal of the flag. A sense of drama is conveyed as the battle ends with a singular heroic sacrifice.

A number of officers are identifiable, as Captain Harvey Smythe holds Wolfe's arm, Dr. Thomas Hinde tries to staunch the general's bleeding, and Lieutenant Colonel Simon Fraser of the 78th Fraser Highlanders is shown in his company's tartan. While these identifiable portraits created a sense of accuracy and historical importance, almost all of them were not at the scene, and their inclusion reflects the artist's intention to compose an iconic image of a British hero. The Indigenous warrior has attracted much scholarly interpretation, including the argument that he represents the noble savage, a concept advanced by the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau who extolled the simpler and therefore nobler character of "primitive" peoples. At the same time, his inclusion also places the scene firmly within the New World, for the artist has carefully selected all the significant elements. For instance, in the background a British soldier is racing toward the group, as he carries the captured French flag. As historian Robert A. Bromley wrote, the overall effect is "so natural...and they come so near to the truth of the history, that they are almost true, and yet not one of them is true in fact."

West innovatively reinterpreted the historical painting by depicting a contemporary scene and clothing his figures in contemporary garb. Sir Joshua Reynolds, along with other notable artists and patrons, urged the artist to depict the figures in classical Roman clothing to lend the event greater dignity, but West replied, "The same truth that guides the pen of the historian should govern the pencil of the artist." Infuriated at Wolfe's use of contemporary clothing, King George III declined to purchase the work, and the artist, subsequently, gave it to the Royal Academy where it became widely popular. William Woollett's engravings of the painting found an international audience, and West was commissioned to paint four more copies of the painting. The work, influencing the movement of many artists toward contemporary history painting, paved the way for David's Oath of the Tennis Court (1791) and John Trumbull's Declaration of Independence (1787-1819). Its cultural influence continued well into the modern era, as, during the British Empire, as historian Graeme Wynn noted it, "became the most powerful icon of an intensely symbolic triumph for British imperialism," and in 1921 the British donated the work to Canada in recognition of their service in World War I.

Oil on canvas - National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada

Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss

The work draws upon the mythological story of Cupid and Psyche as told in The Golden Ass (c. 180) a Latin novel written by Lucius Apuleius. Venus, the goddess of love, was jealous of Psyche, widely admired for her beauty, and sent her son, Cupid, so that his arrows would make the girl marry the ugliest of men. Instead, Cupid fell in love with her, and, learning that the two were lovers, Venus sent Psyche to bring back a jar containing a "divine beauty" from the underworld. Though instructed to not open the jar, Psyche did so, only to fall into the sleep of the dead, as the jar actually contained the "sleep of innermost darkness." This sculpture depicts the moment when Cupid revives Psyche with a kiss. The flowing lines of Psyche's reclining form are echoed in the drapery that partially covers her, and Cupid's melting embrace. Dubbed in his time as the "sculptor of grace and youth," Canova here creates a sense of heroic and innocent love, triumphing over death itself.

Canova's innovative sculptural technique allowed him to convey the effect of living skin, feathered wings, realistically folding drapery, and the rough rock at the base. Reflecting a Neoclassical scientific approach, his study of the human form was rigorous, as he employed precise measurements and life casts in preparation for working on the marble.

For his depiction of Cupid, he was inspired by a Roman painting, which he had seen at the excavation site of Herculaneum. Yet, while firmly posited within Neoclassicism, this work's emphasis on emotion and feeling prefigures the Romantic movement that followed.

The statue has a handle near the base, as like many of Canova's works it was meant to revolve on its base, emphasizing the work's movement and feeling. This innovative decentering of a singular viewpoint was faulted by some critics of the time, including Karl Ludwig Fernow, who wrote, "the observer strives in vain to find a point of view...in which to reduce each ray of tender expression to one central point of convergence." Yet this fluidity of perception created a more intimate relationship to the viewer.

Colonel John Campbell commissioned the sculpture in 1787, and both its treatment and its subject became widely popular with later artists, including the leading 19th century British sculptor, John Gibson, who studied with Canova in Rome.

Marble - Musée du Louvre, Paris

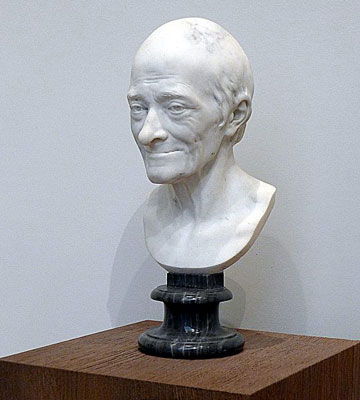

Voltaire

This bust depicts the noted French philosopher and writer, François Marie Arouet de Voltaire, whose wit and intellectual prowess dominated the Neoclassical era. The work is remarkably realistic, its modeling capturing the features of the philosopher toward the end of his life, his thinning hair, the smile lines around his mouth, and his wrinkled brow. Depicted tête nue, or bare-headed without the wig that was fashionable for French aristocrats, the portrait takes on the realism and simplicity of classical Roman busts, allowing the force of the subject's personality to shine forth unimpeded. Houdon captures the sense of Voltaire's shrewd intelligence, as his gaze seems amused with his own interior thoughts.

Count Alexander Sergeyvitch Stronganoff brought this portrait to Russia during the reign of Catherine the Great, who corresponded with Voltaire was devoted to his work. She commissioned several portraits, as well as Houdon's Voltaire Seated in an Armchair (1781), which depicted the philosopher wearing a toga, as if the embodiment of classical Greek philosophy.

Houdon's innovations included his scientific accuracy, as he employed calipers to measure his subject's features and life casts, and pioneered a technique for sculpting eyes that allowed them to capture the light. As art historian John Goldsmith Phillips described, "He first cut out the entire iris, and then bore a deeper hole for the pupil, taking care to leave a small fragment of marble to overhang the iris. The effect is a vivacity and mobility of expression unrivalled in the long history of portrait painting or sculpture."

Considered the greatest portraitist of the Neoclassical era, Houdon portrayed the intellectual and political leaders of the day including George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and Napoleon Bonaparte. Capturing not only their exact likeness, he captured their essence. As art historian Johanna Hecht wrote, "The Enlightenment virtues of truth to nature, simplicity, and grace all found sublime expression through his ability to translate into marble both a subject's personality and the vibrant essence of living flesh, their inner as well as outer life." These portrayals have become part of the public consciousness of these figures, reproduced in countless textbooks, plaster copies, and on national stamps and coins. Houdon's portrayal of Thomas Jefferson is used on the U.S. nickel.

Marble on grey marble socle - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Oath of the Horatii

This image depicts the Horatii, a Roman family, central of which are its three sons, dressed for battle, who extend their right arms in a gesture of allegiance toward their father who holds up three swords. They are about to go to war with brothers from a family of an opposing city. On the right, two women that have family on both sides, arms slack at their sides, swoon toward one another in an attitude of despair, fearing for those that will be killed. In the shadowed background, another woman dressed as if in mourning, consoles the children. The minimal setting with its three rising arches, opening into nearly black shadow, creates a feeling of somber resolve. The painting stresses the importance of patriotism and masculine self-sacrifice for one's country. It became a metaphor for the French Revolution, in which countrymen were enrolled in the idea of killing each other toward the greater good.

When the painting was exhibited at the 1785 Salon, David was acclaimed as the greatest French painter since Poussin. As art critic Roberta Smith wrote, the painting became, "a veritable cornerstone of Neoclassicism. It announced the triumphant return of the grand tradition of Poussinian history painting, and answered the prayers of critics who had been fulminating against the decadence of court painting for years, with Boucher as main scapegoat...[and] gave visual form to the ideas of the French Revolution before the fact."

David's work became widely influential, informing the work of the subsequent generation including Gros and Ingres, as well as influencing the Romantic artists Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault, even as their movement rebelled against Neoclassicism.

Oil on canvas - Musée du Louvre, Paris

Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi, Pointing to her Children as Her Treasures

This painting depicts an encounter between Cornelia, clad in brown and white, who was the mother of the future political leaders Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, and a Roman matron, clad in red who sits to the right. The visitor has come to show Cornelia her luxurious treasures, but when Cornelia is asked to show the visitor her own treasures in return, rather than presenting her own box of jewels, she humbly brings her children forward as her greatest gems. Even as a sort of embarrassment crosses the woman's face, Cornelia's point is clear; a woman's most prized possessions are not items of material worth, but her children who will forge the future. The Roman architectural setting is simple but monumental, framing the view of the distant mountains and sky, and also framing the two women, so that Cornelia's gaze and the other woman's surprised expression both inhabit the rectangular space, emphasizing the painting's message of exemplum virtutis, or model of virtue.

Kauffman created her own signature brand of historical painting that focused on female subjects from classical history and mythology. By emphasizing a mother's virtue as the source of her children's virtue, and, by extension, of social and political justice, Kauffman created an interpretation of classical heroism and idealism that included women. At the same time, as art historian Meredith Martin wrote, she sought "to undermine the dominant conventions of the history genre itself, and to provide her audiences with a different means of experiencing history and its representations," and, as a result, played a "significant role in reshaping eighteenth-century European society's attitudes toward creativity, selfhood, and gender identity."

Kauffman was enormously acclaimed when she arrived in London in 1766, as a London engraver remarked, "The whole world is Angelicamad," and she became a founding member of the Royal Academy in 1768. Having arrived from Rome where she was a close friend with Winckelmann and his circle, she "was," as art critic Jonathan Jones wrote, "a key populariser of a new, pared-down, archeologically-informed classical manner in Britain." Kauffman's work influenced a number of artists in England including Joshua Reynolds, and she was one of only two women who were founding members of the Royal Academy. Her impact was such that the Romantic artist John Constable remarked that no progress could be made in art until her influence was forgotten. In the 1970's her work was 'rediscovered' by feminist scholars including Linda Nochlin and the Guerrilla Girls.

Oil on canvas - Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia

Le Panthéon

This photograph shows the monumental façade of the Panthéon, its portico with massive Corinthian columns rising to a triangular frieze, reminiscent of classical Greek temples. The columns with richly embellished capitals draw one's attention upward to the dome, which was influenced by the Renaissance architect Bramante's Tempietto (1502). At the same time, the vertical lift of the columns, contrasting with strong horizontal lines, creates an overwhelming effect of orderly grandeur dominating the view of Paris. As architectural historian Dennis Sharp wrote, the design exemplifies a "strictness of line, firmness of form, simplicity of contour, and rigorously architectonic conception of detail."

King Louis XV commissioned the building, originally known as Church of Sainte-Geneviève, to fulfill his 1744 vow that, if he recovered from a serious illness, he would rebuild the church, dedicated to the patron saint of Paris. Soufflot used a Greek cross plan, influenced by the designs of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome and St. Paul's Cathedral in London, both churches that he hoped the Panthéon would rival. By drawing upon a number of influences, he reflected the Enlightenment view that, as history followed an orderly and linear progression, past examples could be studied in order to extract the best solutions. At the same time, he innovatively used a triple dome, which, through an oculus in the inner dome, allowed a view into the second dome painted with Antoine Gros's fresco The Apotheosis of Saint Genevieve (c. 1812). After Soufflot's death in 1780, his student Jean-Baptiste Rondelet completed his design, though the façade underwent further changes during the Revolution.

The original church had a vast crypt, containing the relics of Sainte Geneviève and other religious notables, but, subsequently, has become a secular mausoleum for those designated as "National Heroes," including Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and, later, Victor Hugo and Émile Zola. The monumental edifice was the first of many Neoclassical buildings that became symbols of national pride and identity, as other nations, including the United States, widely adopted the style for official buildings.

Paris, France

Achilles Receiving the Ambassadors of Agamemnon

This Neoclassical painting depicts a scene from Homer's Illiad (8th century B.C.E.). The epic poem describes the Trojan War, when King Agamemnon sent Odysseus along with other Greek warriors, to try and persuade the famed warrior Achilles, shown on the left, to rejoin the battle against the Greeks. Emphasizing the classical nude, a powerful contrast is created between the hard muscularity of the men coming from the battlefield, and the languid sensuality of Achilles and his friend Patroculus, sinuously posed at his right. Insulted by Agamemnon's taking of the young woman Briseis, Achilles had withdrawn from the battle, and in this work his body language, as he springs forward, creates a moment of psychological drama. Odysseus, his red cloak, symbolizing passion and war, stands with arm outstretched as if appealing to reason. Between the two groupings, the view opens to a landscape where a group of warriors are training, while in the left background, a young woman looks out of the shadows, her presence evoking the original cause of the quarrel. Each detail is telling, as the lyre symbolized the immortality granted by songs of praise, and Patroculus wears the helmet of Achilles, prefiguring events to follow.

Trained by Jacques-Louis David in the Neoclassical style, Ingres won the Prix de Rome in 1801 with this painting. The competition's topic was to depict warriors preparing for battle. Ingres showed his knowledge and mastery of Neoclassical subjects by depicting Homer's precise description and drew upon a sculpture by Pseudo-Phidias for its historically accurate cloak. Ingres added his own signature contribution by emphasizing the psychological moment, and subtly exaggerating the men's physiques for sensual and emotional impact. As art historian Carol Ockman wrote, "Ingres drew on a wide range of visual and literary representations... But ...transformed these models, first by conflating their historical and mythological vocabularies and then by positioning his own figures within a complex bipartite composition, which... subverts, at least in part, the very gender binarism he intends to inscribe."

Oil on canvas - École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, France

Monticello

This photograph shows the west portico of Thomas Jefferson's renowned plantation home, exemplifying a Neoclassical style influenced by the designs of the Venetian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio. The portico employs four colored columns rising to a triangular pediment to create a grand but harmoniously ordered entrance, emphasizing the octagonal dome that was based upon the Temple of Vesta in Rome. The octagonal dome became a defining element of Jefferson's architecture. Here, he innovatively elongated the dome and made the windows half clear and half mirrored glass to allow for more light. He employed a radical zigzag design for the roof, creating interlocking pieces of sheet iron. The columns, too, were of unique design; though they resemble traditional stone columns, they are actually made of specially curved bricks. The central portico with its vertical orientation emphasizes the flow of the building, so that it seems to have two wings, its horizontal order created in part by the symmetrically placed white framed windows against the reddish brown stone. The building creates a sense of harmonious ease, presiding over the surrounding landscape.

Jefferson inherited the plantation, about 5000 acres, from his father when he was 26. He built the house on the summit of a hill, overlooking the plantation where slaves first cultivated tobacco, then wheat. The name is Italian, meaning "little mount," and the house we see today was actually Jefferson's redesign of the house according to Neoclassical principles, which he studied during his tenure as Minister of the United States to France in 1784. His design became widely influential, setting the standard for wealthy country estates and residences.

The site is a National Historic Landmark, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and is featured on the back of the United States nickel. During his Presidency, Jefferson's architectural ideas also informed official architecture, as he appointed Benjamin Henry Latrobe to design the Bank of Pennsylvania and the U.S. Capitol building in a Neoclassical style, which became known as "Federal architecture."

Stone, bricks, wood, sheet iron - Albemarie County, near Charlottesville, Virginia

Beginnings of Neoclassicism

Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain

Neoclassicism adopted the hierarchy of painting that was established by the French Royal Academy of the Arts in 1669. History painting, which included subjects from the Bible, classical mythology, and history, was ranked as the top category, followed by portraiture, genre painting, landscapes, and still lifes. This hierarchy, was used to evaluate works submitted for the Salon or for prizes like the illustrious Prix de Rome, and influenced the financial value of works for patrons and collectors. The works of Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain were revered as the ideal exemplars of history painting, and both artists were primary influences upon Neoclassicism.

While Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain were both French Baroque artists who spent most of their working lives in Rome, it was their distinctive emphasis on a more classical approach that appealed to Neoclassical artists. Claude, as he is commonly called, painted landscapes, using naturalistic detail and the observation of light and its effects, with figures from mythological or Biblical scenes, as seen in his A landscape with Apollo guarding the herds of Admetus and Mercury stealing them (1645) An effect of orderly harmony was conveyed in many of his works, which appealed to Neoclassicism's belief that art should express the ideal virtues.

While he was also a noted painter of religious subjects, Nicholas Poussin's mythological and historical scenes were his primary influence on Neoclassicism. His The Death of Germanicus (1627) made him famous in his own time, and influenced Jacques-Louis David as well as Benjamin West whose The Death of General Wolfe (1770) draws upon the work. Though the works of Venetian Renaissance artist Titian influenced his color palette, Poussin's compositions emphasized clarity and logic, and his figurative treatments favored strong lines.

The Grand Tour

Neoclassicism was inspired by the discovery of ancient Greek and Roman archeological sites and artifacts that became known throughout Europe in popular illustrated reports of various travel expeditions. Scholars such as James Stuart and Nicholas Revett made a systematic effort to catalog and record the past in works like their Antiquities of Athens (1762). Wanting to see these works first hand, young European aristocrats on the Grand Tour, a traditional and educational rite of passage, traveled to Italy "in search of art, culture, and the roots of Western civilization," as cultural critic Matt Gross wrote. Rome with its Roman ruins, Renaissance works, and recently discovered antiquities became a major stop. Famous artists, such as Pompeo Batoni and Antonio Canova, held open studios as many of these aristocratic tourists were both avid collectors and commissioned various works.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann

Neoclassicism began in Rome, as Johann Joachim Winckelmann's Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture (1750) played a leading role in establishing the aesthetic and theory of Neoclassicism. Though German, he lived most of his life in Rome where several notable Catholic officials became his patrons. Arguing that art should strive toward "noble simplicity and calm grandeur," he advocated, "the one way for us to become great, perhaps inimitable, is by imitating the ancients." The work, which made him famous, was widely translated, first into French, then into English by the artist Henry Fuseli in 1765.

In 1738, the ruined city of Herculaneum was discovered and excavated, followed by the excavation of Pompeii and Paestum in 1748. In the sudden eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE the cities had been covered in volcanic ash, so that elements of ancient everyday life, noted sculptures, and many frescoes were preserved. In 1758 Winckelmann visited the excavations, and published the first accounts of the archeological finds in his Letter about the Discoveries at Herculaneum (1762).

Winckelmann's masterwork History of Ancient Art (1764) became an instant classic, as art historians Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny wrote, his "most significant and lasting achievement was to produce a thorough, comprehensive and lucid chronological account of all antique art - including that of the Egyptians and Etruscans." He was the first to create an orderly vision of art, from beginning to maturity to decline, looking at a civilization's art as integrally connected to the culture itself. The book influenced noted intellectuals both of his time and in the following centuries, including Lessing, Herder, Goethe, Nietzsche, and Spengler.

Early Neoclassicism: Anton Raphael Mengs

Influenced by his close friend Winckelmann, Anton Raphael Mengs was an early pioneer of Neoclassical painting. The circle of artists that gathered around Mengs and Winckelmann positioned Rome as the center of the new movement. Mengs noted frescoes, depicting mythological subjects led to his being dubbed "the greatest painter of the day." He influenced a number of noted artists, who were to lead the subsequent development of Neoclassicism in Britain, including Benjamin West, Angelica Kauffman, John Flaxman, and Gavin Hamilton. He also influenced Jacques-Louis David, who led the later period of Neoclassicism centered in France, as the two artists met during David's Prix de Rome stay from 1775-1780.

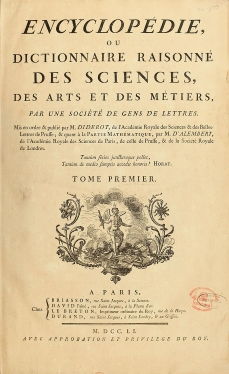

The Enlightenment

Neoclassicism developed with the Enlightenment, a political and philosophical movement that primarily valued science, reason, and exploration. Also called "The Age of Reason," the Enlightenment was informed by the skepticism of the noted philosopher René Descartes and the political philosophy of John Locke as the absolutes of the monarchy and religious dogma were fundamentally questioned, and the ideals of individual liberty, religious tolerance, and constitutional governments were advanced. The French Encyclopédie (Encyclopedia) (1751-1772), representing a compendium of Enlightenment thought and the most significant publication of the century, had an international influence. Denis Diderot, also known as a founder of the discipline of art history, who edited the work, said its purpose was " to change the way people think." As historian Clorinda Donato wrote, it "successfully argued...[for]...the potential of reason and unified knowledge to empower human will and ...to shape the social issues." Adopting this view, Neoclassical artists felt art could civilize, reform, and transform society, as society itself was being transformed by the rising forces of the Industrial Revolution, driven by scientific discovery and invention.

Benjamin West and Joseph Wright of Derby

In Britain, the Neoclassicism of Benjamin West, among other artists, took on a more contemporary message, emphasizing moral virtue and Enlightenment rationality. Other artists such as Joseph Wright of Derby created works informed by scientific invention as seen in his An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768) or Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery (1766). Rather than mythological subjects, British artists turned to classical historical accounts or contemporary history like West's The Death of General Wolfe (1770), in which he challenged the academic standards, refusing the advice to depict the soldiers in Roman togas as not based on reason or observation.

The Apex of Neoclassicism: Jacques-Louis David

The later period of Neoclassicism, centered in France, emphasized strong line, austere classical settings lit with an artificial light, and simplified elements to convey moral vigor. Shown at the 1785 Paris Salon, Jacque-Louis David's Oath of the Horatii (1784) exemplified the new direction in Neoclassical painting and made him the leader of the movement. The artist completed the painting while he was in Rome, where he associated with Mengs, and, subsequently, visited the ruins at Herculaneum, an experience that he compared to having cataracts surgically removed. Although Oath of the Horatii (1784), appealed to King Louis XVI, whose government had commissioned it, with its emphasis on loyalty, the painting became subsequently identified with the revolutionary movement in France. The French Revolution was a period of far-reaching political and social upheaval that overthrew the monarchy, established a republic and culminated as a dictatorship under Napoleon inspired by radical new liberalist ideas. The Jacobins, a highly influential political club of the time, adopted the salute of the Horatii brothers as seen in David's The Tennis Court Oath (1791). David's influence was so great that the later period of Neoclassicism was dubbed "the Age of David," as he personally trained artists including Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, François Gérard, Antoine Jean Gros, and Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres.

Neoclassicism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Architecture

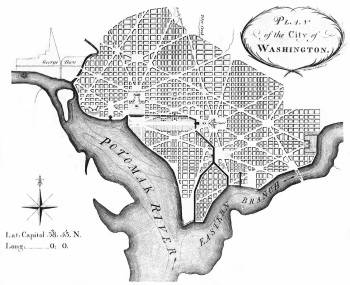

Influenced by Venetian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio's designs and informed by the archeological discoveries at Herculaneum and Winckelmann's theories, Neoclassical architecture began in the mid-1700s and spread throughout Europe. The ensuing style, found in the designs of public buildings, notable residences, and urban planning, employed a grid design taken from classical Roman examples. Ancient Romans, and before them even older civilizations, had used a consolidated scheme for city planning for defense and civil convenience purposes. At its most basic design, the plan emphasized a squared system of streets with a central forum for city services. However, regional variations developed in the early 1800s, as the British turned to the Greek Revival style, and the French to the Empire style developed during the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte. Both styles were connected to a sense of national identity, encouraged by the political environment of the time.

The British Greek Revival style was influenced by the archeological findings of James Stuart and Nicholas Revett who published The Antiquities of Athens (1762), and the discovery of several Greek temples in Italy that could be easily visited. British Greek Revival architecture, led by the architects Williams Wilkins and Robert Smirke, noted for its emphasis on simplicity and its use of Doric columns, influenced architecture in Germany, the United States, and Northern Europe. Carl Gotthard Langhans's Brandenburg Gate (1788-1791) in Berlin was a noted example.

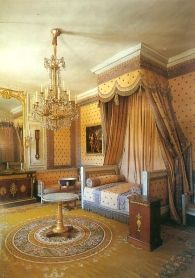

As Hugh Honour wrote, the French Empire style "turned to the florid opulence of Imperial Rome. The abstemious severity of Doric was replaced by Corinthian richness and splendor." Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine, both of whom trained in Rome, were the leading architects of the style, as seen in their Arc de Triomphe du Carousel (1801-1806). The triumphal arch became a noted feature of the style, both in France as seen in the Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile (1806-1836) and, internationally, as seen in the Navra Triumphal Arch (1827-1834) in Saint Petersburg to commemorate the Russian defeat of Napoleon.

Interior Design

Interior design and furnishings in the Empire style were partially influenced by the discoveries at Herculaneum and Pompeii. Empire interiors, meant to impress, employed gilded ornament often with a militaristic motif or motifs evoking ancient Egypt and other civilizations conquered by the Romans, and in the early 1800s conquered by Napoleon. Both in architecture and design, the Empire style became international, as it corresponded to the Regency style in England, the Federal style in the United States, and the Biedermeier style in Germany.

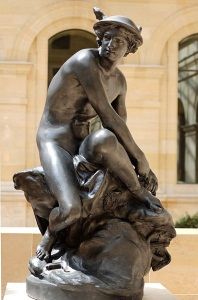

Sculpture

The French Jean-Baptiste Pigalle was an early leader of Neoclassical sculpture. His Mercury (1744) was acclaimed by Voltaire as comparable to the best Greek sculpture and widely reproduced. Pigalle was also a noted teacher, as his student Jean-Antoine Houdon, renowned for his portrait busts, subsequently led the movement in France. As the movement was truly international, the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova was considered to be the leading exponent of Neoclassicism as his works were compared in their beauty and grace to those of the ancient Greek sculptor Praxiteles. In England, John Flaxman was the most influential sculptor, known not only for his figures such as his Pastoral Apollo (1824) but his reliefs and his Neoclassical designs for Josiah Wedgwood's Jasperware, an internationally popular stoneware.

Later Developments - After Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism in painting and sculpture began declining with the rise of Romanticism, though in the early 1800s the two styles existed in rivalry, as Ingres held to Neoclassicism, by then considered "traditional," and Delacroix emphasized individual sensibility and feeling. By the 1850s Neoclassicism as a movement had come to an end, though academic artists continued to employ classical styles and subjects throughout most of the 19th century, while opposed and challenged by modern art movements, such as Realism, Naturalism, and Impressionism.

Nonetheless Ingres' work continued to influence later artists as he evolved away from Neoclassicism and into Romanticism with his female odalisques and their elongated backs. He impacted Edgar Degas, Auguste Renoir, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso, who were informed by his figurative treatments with their stylistic distortions. David's work, particularly his The Death of Marat (1793), was rediscovered in the mid-19th century, and, subsequently, influenced Picasso and Edvard Munch, as well as contemporary artists such as Vik Muniz. Contemporary artist Cindy Sherman's History Portraits (1988-1990) repurposes a number of famous Neoclassical works through self-portrait film stills.

While Neoclassical architecture declined by the mid 1800s, its influence continued to be felt in new movements, such as the American Renaissance movement and Beaux-Arts architecture. Additionally, architects commissioned to create noted public projects continued to turn to the style in the 20th century as seen in the Lincoln Memorial (1922) and the American Museum of Natural History's Theodore Roosevelt Memorial (1936). The Soviet Union also frequently employed the style in state architecture, both at home and by exporting it to other communist countries.

Useful Resources on Neoclassicism

-

![Neoclassical Art]() 7k viewsNeoclassical ArtArt History

7k viewsNeoclassical ArtArt History -

![Heroes of the Enlightenment]() 0 viewsHeroes of the EnlightenmentOur PickBBC

0 viewsHeroes of the EnlightenmentOur PickBBC -

![The Pantheon, Paris]() 65k viewsThe Pantheon, ParisWorldSiteGuides

65k viewsThe Pantheon, ParisWorldSiteGuides

-

![Jacques-Louis David with Simon Schama]() 59k viewsJacques-Louis David with Simon SchamaOur PickBBC

59k viewsJacques-Louis David with Simon SchamaOur PickBBC -

![An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump]() 7k viewsAn Experiment on a Bird in the Air PumpOur PickBy Benjamin Woolley / BBC

7k viewsAn Experiment on a Bird in the Air PumpOur PickBy Benjamin Woolley / BBC -

![Enlightenment and Beauty: Sculptures by Houdon and Clodion]() 7k viewsEnlightenment and Beauty: Sculptures by Houdon and ClodionBy Anne L. Poule / The Frick

7k viewsEnlightenment and Beauty: Sculptures by Houdon and ClodionBy Anne L. Poule / The Frick -

![Benjamin West, "Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky"]() Benjamin West, "Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky"Philadelphia Museum of Art

Benjamin West, "Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky"Philadelphia Museum of Art