Summary of Jean-Léon Gérôme

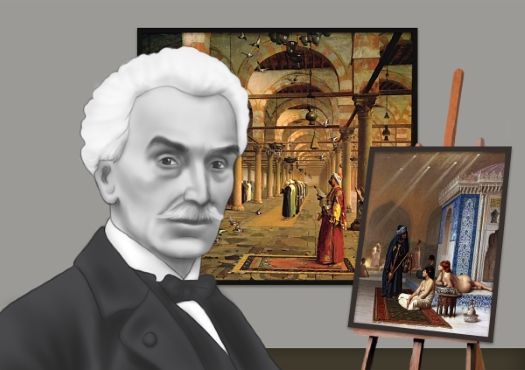

Though the exotic, and sometimes scandalous, subject matter of his paintings attracted disapproval, there can be no doubt that Jean-Léon Gérôme was a technical maestro; a master of the spectacular who prided himself on a meticulous attention to picture detail. One of the most famous French painters of his generation, he can be credited with bringing about a transformation in historical painting. He was, however, subject to fierce criticism and controversy (mainly from Realists and Expressionists) who viewed his blending of academic painting with genre painting as falling somewhere between two outmoded schools. Nevertheless, Gérôme, whose pictorial worlds could certainly not be relied upon for historical accuracy, captivated a public that was won over by the skill and theatricality of his art. In his later career Gérôme reinvented himself as a sculptor, but he remains best known for his spectacular historical narratives that were made even more popular through the photographic reproduction of his images.

Accomplishments

- Emerging as a force during the dawning of French modernism, Gérôme gained a reputation as something of a conservative dissident. Closely aligned to the "passé" (from a modernist's point of view) tropes of Neoclassicism, Naturalism and Orientalism, he antagonized the Parisian avant-garde community with his art and his vocal opposition to the rise of Impressionism, which he saw as unskilled and incompetent.

- Gérôme's numerous paintings of the Orient revealed at once his strength and weakness. His meticulous and precise images lent a veneer of authenticity to a fantasy of the Orient that was rendered complete and untouched. While this skill did not win over the elders of the art establishment, it proved hugely popular with ordinary art lovers who purchased reproductions of his art in substantial quantities.

- Though he predates the maturation of narrative cinema, his work has been described retrospectively as "cinematic". This description refers to a style of painting that creates powerful and overwhelming pictorial illusions of historical worlds in a style that comes close to photographic realism. Indeed, his paintings lent themselves to photographic reproduction with still copies of his work able to reach a broad public.

- Gérôme was a founding member of the so-called Neo-Grec Circle. Formed in in 1847, it comprised of a group of young artists who wanted to bring a higher standard of detail and archaeological accuracy to Greco-Roman antiquity painting.

- Gérôme was sometimes referred to as "The Father of Polychromy", a name given to the classical discipline of painting onto a marble sculpture. His polychrome sculptures drew thus on references from antiquity but to which he added a sense of modern day realism.

The Life of Jean-Léon Gérôme

Art critic Jonathan Jones described Gérôme’s well-known painting The Snake Charmer as “a sleazy imperialist vision of ‘the east’.” Given today’s multicultural view of the world, it is hard to look at the French artist’s work with the same eyes as his nineteenth-century audience. But the work is fantastic and spectacular nonetheless.

Important Art by Jean-Léon Gérôme

Young Greeks Attending a Cock Fight (also called The Cock Fight)

This genre painting was a huge success when it was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1847. It shows two adolescents, seated privately at the base of a relic. In front of them two cocks fight to the death in what was a traditional sport of classical Greece. In the foreground, the boy holds one animal as he kneels in front of verdant greenery. Behind him, semi-nude, a beautiful young woman recoils from the fight. Behind her the turquoise Aegean sea can be seen, and beyond that a Grecian mountain backdrop.

Gérôme was a skilled animal painter and a lover of nature, and believed the study and representation of animals to be an essential part of the complete artist's training. But the work was positioned badly in the salon, "hung so high...as to hide it from the viewing eye", according to Gérôme. Nevertheless, it still met with critical acclaim, launching him into the avant-garde as leader of the Néo-Grecs. Championed by Art Critic Théophile Gautier, who saw "wonders of drawing, action and color" in the work, the painter Victor Mottez added to the praise when he said Gérôme was the "pearl of the Salon" (praise indeed for a work exhibited along-side Auguste Rodin's The Thinker).

The Néo-Grecs turned their back on the solemnity of classicism, seeking more joyous themes. This work represents what would become Gérôme's signature; a subject taken from history and transformed in his imagination. In his smooth, academic style he renders an image made from mosaics in Naples, frescoes from Pompeii and images from the Italian Renaissance. The academic influence of Jacques-Louis David is evident too in his faithful realism and attention to detail. But as Louvre chief curator Dominique de Font-Réaulx said: Gérôme "added a new dimension by seeking to base his painting on the most recent archaeological, ethnographic and historical research." This went on to inspire a "flock of imitators", known as the Pompeians. Not everyone was impressed however. Charles Baudelaire (who happened to be a great friend of Manet) condemned "an artist who substitutes the entertainment provided by a page of erudition for the pleasure of pure painting" and dismissed Gérôme as the leader of what he dismissively called the "meticulous school."

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Ave Caesar, Morituri Te Salutant (Hail Caesar! We Who Are about to Die Salute You)

This spectacular work shows a gladiatorial contest at the Colosseum in Rome - a subject seldom selected for history painting. In the darkened foreground a warrior lies dead; all around him in the sand lay discarded weapons and armor. Behind a man throws sand over the patches of blood, and beyond him other men pull dead bodies from the arena. In the centre is a group of eight gladiators, shouting the words of the title to the Emperor Vitellius who sits above. Sitting to his left are a group of vestal virgins. The light behind shines on the thousands of spectators housed in the curved sweep of the colosseum.

Gérôme liked to present panoramic visions of history; focusing not on individuals or faces, but on vast scenes that took in crowds, architecture, culture and geography. Critics and the public alike were astounded by the work which was the result of Gérôme's meticulous research. He studied architectural drawings of the Colosseum, made countless studies of gladiators and their weaponry and even included the web-like structure that held up the awning protecting the richer members of the audience from the Roman heat. Yet Gérôme's paintings were not historically accurate which diminished his standing as a serious painter. Here, for instance, it was remarked upon that construction of the Colosseum had not begun until 11 years after Vitellius took up office.

Throughout the 19th century, critics complained that history painting, which depicted classical and/or modern historical events in what was known as the "grand style," was becoming contaminated by the more intimate and overtly sentimental genre painting. History painting was supposed to be grand, truthful and moral, but as art historian Laurence des Cars noted, Gérôme's "visual system [which was] based on a very relative neutrality was put in the service of subjects that were themselves considered in terms of minor events and triviality." Des Cars noted however that though a "certain kind of history painting was indeed dead", the new animation of "narrative and images [...] had only just begun," with Gérôme singled out as its starring protagonist.

Oil on canvas - Yale University Art Gallery, Connecticut

The Death of Caesar

The Death of Caesar became one of America's favorite Gérôme paintings. The work shows the immediate aftermath of the Roman emperor's assassination, as his joyous killers, hands aloft, seem to dance away from the body. We see a faithful depiction of the art, statuary and architecture, which Gérôme studied while visiting Rome. The scene, set in the Theatre of Pompeii, was however staged in an unconventional style for the time: the subject of the piece, while foregrounded, is secondary to the action of the conspirators. Caesar's body is abandoned in the dark to the left of the canvas, while the narrative is centered on the group of jubilant knifemen.

This composition would have an influence on other history painters. Des Cars wrote: "Its evocative power and its consummate mastery of visual theater, characterized by the favorite device of the central void, was to be a lasting influence on the way other painters depicted and staged drama." Even a grudging Baudelaire was impressed. He remarked: "This time, certainly M Gérôme's imagination has been carried away! [...] Criticism has been leveled at this way of presenting the subject but it deserves great praise. The effect is truly powerful." The work was brought by the American collector John Taylor Johnston.

Oil on canvas - The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland, US

The Execution of Marshall Ney

Gérôme's lively imagination can best be seen in this work, which has been described as one of his most surprising paintings. The victim, who lies face down in the mud in the foreground, is Michel Ney, one of Napoleon Bonaparte's most brave and loyal generals. He was however convicted of treason by the new Government shortly after the battle of Waterloo and shot unceremoniously in a squalid corner of Paris. Gérôme paid careful attention to Ney's body, his hands and his suit, while the fine detail in the grubby wall and the muddy foreground merely emphasize the scale of the General's fall from grace. In the distance, however, the brushwork is less carefully rendered, depicting the killing squad's movement and adding to the scene's sense of matter-of-factness. In what was a self-conscious challenge to convention, Gérôme once again focuses on the immediate aftermath of an historic event.

It was important for his relevance as an artist that Gérôme found a new mode, especially so given the fact that, by the mid-nineteenth century, French art was on the cusp of a new dawning. The Realists such as Gustave Courbet, Jean Francois Millet and Rosa Bonheur had already rejected foreign influences and historical and mythological subject matter in favor of realistic images. Though they still used traditional painterly methods, artists like Édouard Manet were beginning to experiment with more impressionistic techniques. Indeed, Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergère would soon change the direction of modern art altogether. Exhibited at the Salon in 1882, the Impressionist had caused a scandal within the art establishment by introducing a dubious morality (the Folies-Bergère was a notorious haunt for picking up prostitutes) to the realm of high art. History painting was being knocked from its pedestal, and the viewing public was insisting on new ways to see and interpret the present. For those still invested in historical painting "the facts" were therefore no longer enough and they demanded a novel dimension of psychology and drama. Whether this approach was viewed as a progressive or regressive depended on one's view of the role of the artist. As curator Scott C. Allan explained: "While a few sympathetic critics found a chilling dramatic frisson in Gérôme's descriptive deadpan, most accused him of perversely avoiding all that was potentially grand, heroic and pathetic in the subject. By highlighting the drama's ignoble aftermath rather than its emotional climax, Gérôme's painting constituted an evasion." Indeed, these types of criticism were grounded in the belief that the historical painter should be, if they were to warrant that honorable title, possessed of a certain dependability and conscientiousness.

Oil on canvas - Museums Sheffield, UK

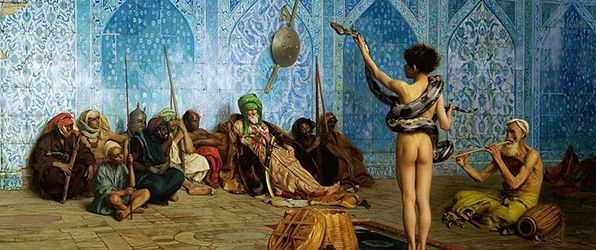

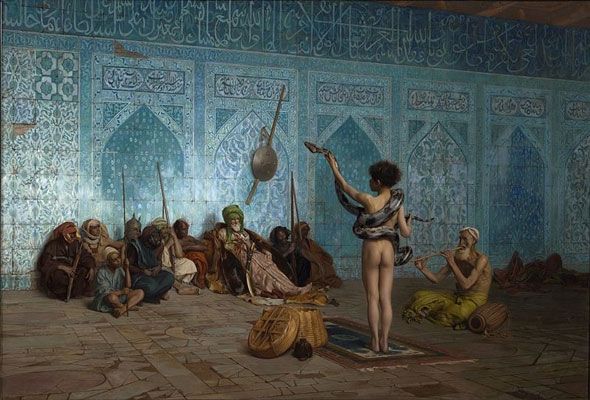

The Snake Charmer

Rendered in Gérôme's trademark highly detailed and decorative style, we see a young boy holding a python as an old man plays a recorder to his right. The boy is naked, apart from the reptile which is double-wrapped around his body, its head held aloft by the boy. In the background, a group of ten men in Islamic tribal dress look on, holding staffs and weapons. They are seated on the floor against a backdrop of a beautiful eastern tiled wall, shining in azure, cyan, turquoise and aquamarine. The viewer is perhaps invited to judge the men, but to Western audiences, for whom the Orient and its people was a mystery, the work's primary function was to titillate.

The painting was inspired by a trip to Constantinople, and along the top of the wall we see Arabic text. Like many of the artist's canvases, it was a composite, put together in his studio from studies he made abroad. As such, errors and inconsistencies slipped in. Gérôme's tight, realistic style paints an intriguing picture, but the work has been widely rebuked by contemporary critics. Indeed, art critic Jonathan Jones called it a "sleazy imperialist vision of 'the east'", and the work even adorned the cover of Edward Said's seminal 1978 text Orientalism, a book that took Western culture to task over the way it had patronized the far East and its societies and customs. Jones continued: "The Snake Charmer is such an obviously pernicious and exploitative western fantasy of 'the Orient' that it makes Said's case for him." Art historian Linda Lochlin described it meanwhile as a "visual document of nineteenth-century colonialist ideology, an iconic distillation of the Westerner's notion of the Oriental couched in the language of a would-be transparent naturalism." Such criticisms rather ignores the fact that, despite his aesthetic play on fine details, Gérôme had based his painting on what he had witnessed first-hand.

Oil on canvas - Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts

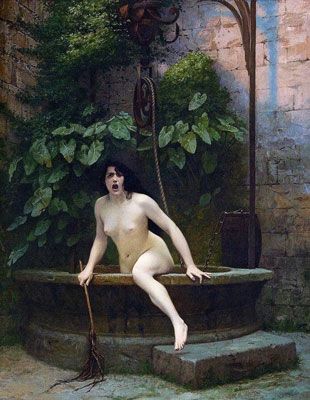

The Truth Coming Out of Her Well to Shame Mankind

This late work, one of three depicting the same subject. shows a pale, naked woman, emerging from the well of the title. She is in motion, lurching towards the spectator, her mouth open in either an expression of anger or exclamation. In her right hand she holds a switch, possibly to use in attack, and her obvious anger is at odds with her naked vulnerability. The pallor of her skin is emphasized by the dark, cold looking stone and the depths of the foliage behind her. Above, a ghostly blue and red light is cast on the brickwork, setting the scene at sunset.

In this strange, compelling painting, the message behind Gérôme's narrative is ambiguous. The artist seldom produced allegorical pieces, and the meaning behind this painting has been the subject of debate. On a denotative level, the canvas is a literal translation of the Greek philosopher Democritus' saying: "The truth lies at the bottom of the well." However, the Director of the musée national Eugène Delacroix, Dominique de Font-Réaulx suggested that the work served as an affirmation of Gérôme's own artistic choices: "These depictions of the Truth were done by an ageing artist whose manner and style had been severely challenged by a younger generation of artists, notably including the Impressionists, whom he intensely opposed." In this interpretation then, Truth stands for the superiority of his realistic style and his search for accuracy in painting. A review at the time said that the woman is climbing from the well "in great anger" but he or she could not decide "whether she is angry at artists, critics or her dry-cleaner." It is true that the work was not met with the same kind of fanfare that greeted some of Gérôme's early works. Nevertheless, it remains especially relevant today as an unlikely feminist meme which has been re-appropriated online as a symbol of female rage.

Oil on Canvas - Musée Anne-de-Beaujeu, Moulins, France

Corinth

Described by Musée d'Orsay in its index as a "strange and disturbing masterpiece", Corinth was Gérôme's homage to the ancient Greek city of Corinth, the birthplace of painting, sculptural portraiture, the Corinthian architectural column, and also home of the sacred prostitutes who occupied the ancient temple of Aphrodite. The sculpture shows a crossed-legged naked woman bedecked only in jewels. Her gaze is piercing and her demeaner somewhat mysterious and provocative, and when combined with the finery of her jewelled accessories, she represents the figure of an Aphrodite courtesan.

The piece, one of the artist's last works (it was in fact left unfinished by Gérôme, to be completed by his assistant Emile Decorchement and exhibited at the Salon in 1904), shows how he excelled at polychrome sculpting. Indeed, Corinth exemplifies Gérôme's preference for cross-referencing painting and sculpture. It was after 1890 (with Tanagra) that Gérôme shifted towards sculptural polychromy: the technique of painting sculpture or architecture with color that was commonplace in antiquity (typically, classical sculptures are presented unpainted). By painting onto marble with paint made from pigmented wax, Gérôme was attempting to revive that ancient discipline. Here the monochrome of tinted-marble and bronze, the colored wax (in which the jewellery was cast) and the flesh-colored painted finish, combine to create a strong illusion of realism (much like his painting). In keeping with his attention to detail, the figure's jewellery was based on observed Greek and Etruscan examples (on display in The Louvre) while the woman's hairstyle and facial features were very much the style of the turn-of-the-century Parisienne woman. By connecting a classical depiction with the contemporary Corinth was a daring (for some licentious) work, and, in that respect, a career finale quite befitting of the artist's oeuvre.

Polychrome plaster, colored wax, and metallic wire - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Biography of Jean-Léon Gérôme

Childhood

The son of a goldsmith and jeweler, Jean-Léon Gérôme was born in the French provincial town of Vesoul in 1824. An intelligent, studious child, he studied Latin, Greek and history at high school. He was taught drawing by Claude Basil Cariage, a Neoclassical painter and former student of Jean-August-Dominique Ingres. Indeed, a young Gérôme showed an impressive talent for art, and his teacher instructed him to learn from plaster casts and models which he had brought to Vesoul from Paris. In 1838 Gérôme won his first prize for drawing, and his work caught the eye of a friend of the French historical painter Paul Delaroche.

Early Training

By the age of 16, Gérôme had obtained his baccalaureate and he left his hometown for Paris, where he went to study in Delaroche's studio, whom he adored. However, Gérôme had gone against his father's wishes in the move, and struggling to survive, he was forced by circumstance to paint religious cards which he sold on the steps of churches to scratch out a living. For three years Gérôme followed a strict routine; studying from casts in the morning, while painting or sketching en plain air in the afternoon. He was also encouraged to copy engravings and Old Masters in the Louvre and to attend classes at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. His dedication and ability eventually earned his father's approval, who, pleased with his son's rapid progress, gave him a generous allowance of 1,200 francs a year (which Gérôme often shared amongst his friends).

In 1843 Gérôme and Delaroche travelled to Italy; visiting Rome, Venice and Naples. The young artist wrote in his diaries: "This year is one of the happiest and fullest in my life, and at this time I have made many major progresses." Through Delaroche's connections, he met several young artists and burgeoning photographers, including Henri Le Secq, Charles Nègre and Gustave Le Gray. These new acquaintances would go on to influence the cinematographic look of much of his work. Indeed, in 1856, the French poet and novelist Théophile Gautier had championed photography as a means of enabling artists like Gérôme to paint images that were truly faithful to the real world. Gérôme had in fact returned from his first excursion to the Middle East with over a hundred photographs, and though he allowed his imagination to inform his artworks, Gérôme's highly detailed paintings drew on these photographs to represent his own vision of the colorful region.

On his return to Paris, Gérôme studied under Swiss artist Charles Gleyre (Gleyre had taken over Delaroche's studio). Gleyre taught Gérôme how to improve his drawing and to purify his forms. It was under Gleyre's influence indeed that he matured his skill for genre paining and, in 1846, the brotherhood of the "Néo-Grecs" was established. Led by Gérôme (who became the brotherhood's de facto leader following the positive reception of his painting The Cock Fight at the 1847 Salon) and comprising of Gleyre's other students Jean-Louis Hamon, Henri-Pierre Picou and Gustave Boulange, the Neo-Grecs shared a house ("Le Chalet") on 27 rue de Fleurus, Paris. Gérôme remembered the atmosphere of the Neo Grec community thus: "it was the meeting place for all our friends, and there were musicians too. We enjoyed ourselves in a spirit of total harmony."

Mature Period

In 1856, Gérôme embarked upon his first trip to Egypt and the Middle East. He travelled the Nile, visited Cairo, crossed the Sinai Peninsula and explored the Holy Land, including visits to Jerusalem and Damascus. He took inspiration from the North African landscape and its people, producing his first Orientalist works.

Three years later, Gérôme captured the imagination of the American public when two of his paintings were exhibited in New York. As art historian Mary G Morton explained: "During the first half of the nineteenth century, Americans focused on native, morally instructive art, but the crisis and loss of national confidence during the Civil War period led to an emphatic turning outward." This drew critics and collectors back to the Old World, and for a time Gérôme's Orientalism came to represent high art in America. However, his success was also his critical downfall; the more popular his art became, the more derided he became as a progressive artist. Morton added: "He was idealized for his professionalism, his cosmopolitan Frenchness, his intellectualism, erudition and refined technical training. But he was also disdained as overly commercial, and suspected of a characteristically French moral degeneracy that some Americans sought to escape in the reconstruction of their national identity." Despite this criticism, Gérôme could command fantastic prices for his canvasses, and his works were selling for ten to a hundred times more than his (certainly more avant-garde) Impressionist contemporaries.

In 1863, Gérôme married Marie Goupil, the daughter of successful international art dealer Aldophe Goupil, who he had been working with for four years. He described his 21-year-old bride as "a young woman of rare beauty and charming grace." They moved to a townhouse at 6 rue de Bruxelles, near the music hall the Folies Bergère, (immortalized by Édouard Manet's painting of the forlorn bar woman). Their first child, Jeanne, was born that year, and they would go on to have three more daughters and one son. His good fortune continued when, in 1864, he took up a post at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, becoming one of the school's most respected teachers.

Gérôme's professional relationship with Aldophe Goupil - known as "the international powerhouse of contemporary art dealers" - was crucial to the artist's success. Goupil sold photographs and photogravures of modern paintings through offices in New York, London, and Berlin and Gérôme became his most reproduced artist.

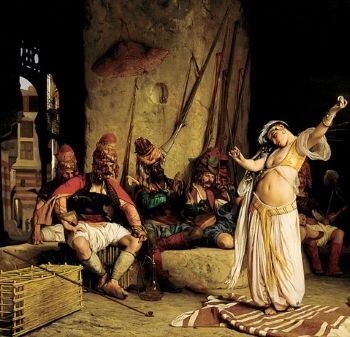

Gérôme, meanwhile, travelled throughout the Europe and the Middle East, visiting Spain, Greece, Turkey, Jerusalem, and Syria. He visited Egypt no less than six times in his life and his tours inspired some spectacular, shocking and provocative paintings, including pictures of slaves waiting to be sold at market, women luxuriating in Turkish baths, a belly dancer entertaining soldiers at rest and severed heads hanging from hooks outside a mosque. He was widely dismissed by intellectuals as a fantasist whose work served only salacious and commercial ends. Indeed, the French writer Émile Zola lambasted Gérôme at Paris's Exposition Universelle of 1897, accusing him of being a "cynical manufacturer of anecdotal images for mass reproduction and popular consumption."

Gérôme was 55-years-old when he discovered sculpture though he tackled it "with all the passion and seriousness of a young artist", according to writer Édouard Papet. By this time Gérôme had also made a name for himself as a vehement anti-Impressionist. In 1884, he fought the École des Beaux-Arts when it staged the posthumous exhibition of Édouard Manet. Gérôme said Manet "was the apostle of a decadent manner, of a piecemeal art" and while he (Gérôme) had been "assigned by the Nation to teach young people the grammar of art" he did not think his students "should be presented with the model of highly willful and lurid art by a man who never developed the rare qualities with which he was endowed."

Around the same time, Gérôme fell from grace in the US; denounced as a corrupting influence on American art. An article in the New York Evening Post in 1882 claimed that Gérôme was an exemplar of the current trend of artists painting purely for popular appeal to attain high prices. The Barbizon School began to take over, and collectors opted instead for the works of artists likes of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau and Jean-François Millet.

Late Period

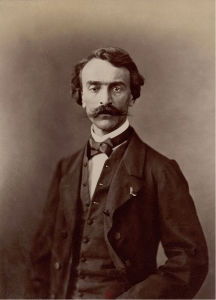

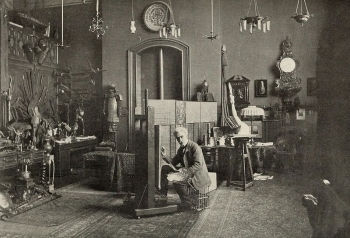

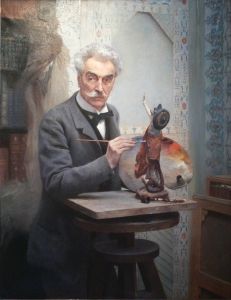

By 1898 Gérôme was nominated Grand Officer, the penultimate rank in the Légion d'honneur and a rare distinction for an artist. He has been described as a man fascinated with appearances - both others' and his own. He dressed well, was proud of his bushy mane and enjoyed being photographed. The Art Journal said Gérôme's look was "peculiar" before adding that "his head, with its deep-set, large eyes, wild masses of grey hair, and pointed grey mustache is eminently picturesque. He is as thin as a shadow, and is distinguished for extreme industry, excessive irritability and extreme dislike of visitors." In the catalogue that accompanied a 2010 Getty exhibition revisiting the Salon painter's work, The Spectacular Art of Jean-Leon Gérôme, Laurence des Cars, Dominique de Font-Reaulx and Edoard Papet stated: "This concern for his appearance certainly reflected a refusal to let himself go, a determination to retain control that was also expressed through his fierce loyalty to scrupulous, meticulous, artistic craft."

Gérôme's concern with his own appearance seemingly informed his own death in 1904, when he died neatly and without fuss in his studio at the age of 80, in front of a portrait of Rembrandt. French writer Albert Soubies wrote that he had succumbed "to death suddenly, in full stride and full energy, without a preliminary period of gradual physical decline. Barely one week ago he could be seen, slim and upright like an officer in civilian clothing." His rank as Legion of Honor entitled him to a funeral of military pageant, but he left instructions for a simpler affair. He was buried in the Montmartre Cemetery in front of his own sculpture, Sorrow. It is estimated that he produced some 600 canvases, sixty sculptures and hundreds of drawings and studies during his lifetime.

The Legacy of Jean-Léon Gérôme

Gérôme's career ran parallel with another French artist, William-Adolphe Bouguereau. The latter's beautifully executed Neoclassical nudes, religious and genre paintings were also hugely popular with the public, but, like Gérôme, Bouguereau divided opinion due in part to his disdain for Impressionism. And, like Bouguereau (and like two more contemporaries, Alexandre Cabanel and Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier), Gérôme fell into critical disrepute after his death. Despite the fact that his work is held in collections by the Louvre Museum and Musée d'Orsay in Paris, The Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in New York and the National Gallery in London (amongst others), Gérôme's relevance, especially in recent decades, has been questioned; his bitter opposition to modern art not helping matters (Gérôme became known in fact as the "anti- Monet"). As art critic Christopher Knight noted, "From Manet to Cézanne, every artist we revere today was on the other side of [the] Gérôme fight."

The authors of The Spectacular Art suggested meanwhile that history had relegated Gérôme to the status of illustrator in that his art "survived primarily, and increasingly anonymously, in the form of pictures that embellished dictionaries, encyclopedias and history textbooks." Gérôme's art was dealt yet another blow with the publication of Edward W. Said's seminal text Orientalism (1978) which railed against the European fetishization of Eastern culture.

Those criticisms notwithstanding, Gérôme's influence can be seen in the work of American artist Thomas Eakins, from whom he learnt the science of observation and Gérôme's heightened sense of realism. Another American artist, Jon Swihart, stated that he was "genuinely obsessed" with Gérôme's "different, exotic, strange, photographic [and] perverse [art]." Even more recently, the 2010 Getty Center's retrospective claimed to reconsider "the variety and complexity of Gérôme's masterful oeuvre" with curator Scott Allan adding that Gérôme had been "one of the most influential art teachers of the nineteenth century [whose] pedagogical reach extended to thousands of students from the United States to the Ottoman Empire." His pupils included the prolific Swiss realist painter Eugene Burnand, the American Impressionist Dennis Miller Bunker, the French academic painter Delphin Enjolras and the famous Russian war artist, Vasily Vasilyevich Vereshchagin. He has also been admired for his epic panoramas with his paintings of battling Roman gladiators cited by producer Walter Parkes and director Ridley Scott as reference points for their 2001 Oscar winning film, Gladiator.

Influences and Connections

-

![Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres]() Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres - Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi

-

![Charles Gleyre]() Charles Gleyre

Charles Gleyre -

![Nadar]() Nadar

Nadar ![Antoine-Louis Barye]() Antoine-Louis Barye

Antoine-Louis Barye- Paul Delaroche

- Emmanuel Fremiet

-

![Henri Rousseau]() Henri Rousseau

Henri Rousseau - Jon Swihart

- Jean-Paul Laurens

-

![Odilon Redon]() Odilon Redon

Odilon Redon -

![Thomas Eakins]() Thomas Eakins

Thomas Eakins - J. Alden Weir

-

![Orientalism]() Orientalism

Orientalism - Neo-Grec

Useful Resources on Jean-Léon Gérôme

- Gérôme: The Life and Works of Jean Léon GérômeBy Fanny Field Hering / Classic Reprint: July 19, 2017

- Jean Léon Gérôme: His Life, His Work 1824-1904By Gerald M. Ackerman / March 16, 2009

- Reconsidering GérômeOur PickBy Scott Allan and Mary Morton / September 14, 2010

- The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme: (1824-1904)Our PickBy Laurence des Cars / October 4, 2010