Summary of William-Adolphe Bouguereau

There are few artists of the modern period whose critical and commercial fortunes during and after their lifetime stand in such stark contrast. In his own era, the Neoclassical painter William-Adolphe Bouguereau was one of the most reputable and commercially successful artists in the Western world, showered with official acclaim and prizes, hugely popular with the art-buying bourgeoisie, and a respected and loved teacher. His religious and mythological tableaux, classical nudes, and Naturalist-influenced scenes of humble peasant life were produced at a prodigious rate, for an endlessly eager public (he once declared that "every minute of mine costs 100 Francs"). But in the decades following his death, when academic painting fell out of favor with art historians and critics, his reputation was significantly reduced, in some cases to that of an establishment huckster, tossing off lifelessly perfect nudes and pietàs for a credulous middle-brow audience. In hindsight, we can see that this latter narrative is unfair: a brilliantly talented draughtsman capable of beautiful figurative paintings, Bouguereau's tastes were simply more traditional, his attitude to his career more acquisitive and pragmatic, than that of his avant-garde peers.

Accomplishments

- Bouguereau has the odd distinction of being mainly renowned for his disagreements with other artists, namely the Impressionists, and other avant-garde groupings of the late-19th century. He scorned them for their lack of technical precision, while they abhorred what they saw as Bouguereau's overly fussy, fastidious approach. The artist himself once stated that " [a]s for the Impressionists, the Pointillists, etc., I cannot discuss them. I do not see the way they see, or claim to see". The Naturalist critic Louis de Fourcaud claimed that "in his observation of nature, [Bouguereau] is always the victim of his desire to improve on it."

- Bouguereau, along with artists such as Alexandre Cabanel and Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, was one of the figureheads of a late generation of Neoclassical painters active during the 1850s-90s. Despite the attention paid to Impressionism and other developments in experimental art during this period, these artists were in fact far more successful during that period itself, with Bouguereau celebrated for his technical mastery of the classical nude, amongst other things.

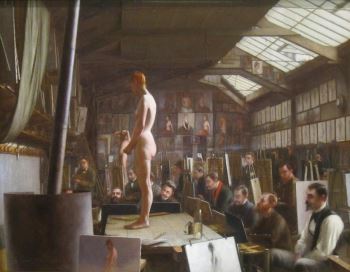

- In spite of his reputation as a force of reaction, Bouguereau was a venerated and - by all accounts - avuncular and encouraging teacher, whose most lasting cultural legacy was his consistent advocacy of the training of female art students at the Académie Julian. A former pupil, the American painter Edmund Wuerpel (1866-1958), described Bouguereau as " [a]lways gentle, always fair, never saying things he did not really mean [...] it was a pleasure as well as a privilege to listen to him."

The Life of William-Adolphe Bouguereau

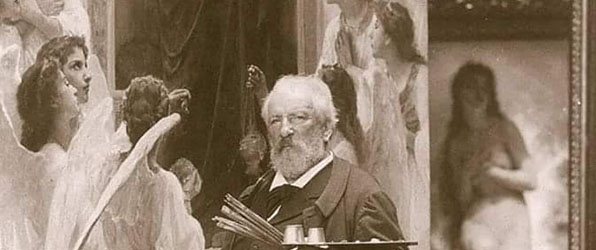

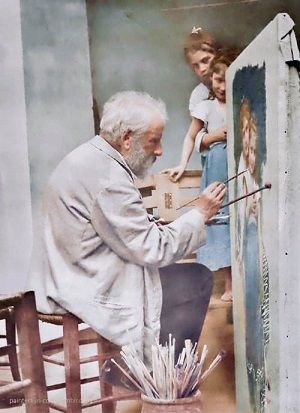

The master and teacher Buguereau here stands proudly in his studio, surrounded by his angelic creations. His works were exemplary to the artists of the academies, and he was the figure the revolutionary artists (Matisse, Degas) attempted to topple.

Important Art by William-Adolphe Bouguereau

Dante and Virgil in Hell

The source material for this painting is Canto XXX from the "Inferno" sequence of the medieval poet Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy (1308-20). In this section, the poet Dante and his guide Virgil descend to the eighth circle of hell, where they encounter the tormented souls of "falsifiers" (counterfeiters and fraudsters). Bouguereau was likely inspired by the following lines from the poem: "As I beheld two shadows pale and naked, / Who, biting, in the manner ran along/ That a boar does, when from the sty turned loose." In the foreground, the wrathful Capocchio - a friend from Dante's schooldays, who was burned at the stake as an alchemist - is attacked by Gianni Schicchi, another of Dante's contemporaries, who had impersonated a dead man in order to steal his inheritance. A demon hovers in the background, while other damned souls writhe around in the fiery landscape.

Bouguereau submitted this atypically macabre work to the Salon of 1850, at a time when he was just establishing himself as an Academic painter. The work garnered significant critical praise, including from the writer Théophile Gautier, who remarked on Bouguereau's attention to musculature and narrative drama. Through his studies at the École des Beaux-Arts, Bouguereau had encountered the works of the great Neoclassical painters, and had absorbed a contemporary fashion for dark subjects from medieval literature. At this early point in his career, he was also concerned with showing off his technical prowess, by capturing unusually strained nude poses.

Bouguereau would not return to Dante, soon discovering that - in his own words - "the horrible, the frenzied, the heroic does not pay", and that the public preferred Venuses and Cupids. Nevertheless, he retained the exquisite skill in figure painting which is clear from this work. Composed the same year as his breakthrough painting Zenobia Found by Shepherds on the Banks of the Arax (1850), which earned him the Grand Prix de Rome, this painting thus marks the point in Bouguereau's career when he established himself as a champion of the Academic style.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Pietà

For this ambitious religious work, Bouguereau devised a large-scale interpretation of the classic Pietà theme, showing the Virgin Mary mourning the body of Christ. At the center of the composition, consumed by her black veil, Mary cradles her child, entreating the viewer to pity with her gaze. Golden aureoles, resembling the gold-leaf details on Renaissance icons and altar-work, surround the heads of the two central figures, while a group of mourning angels encircles the scene, echoing the central compositional shapes.

A year before completing the painting Bouguereau had suffered the traumatic loss of his teenage son George to a sudden illness. Contemporary correspondence reveals the artist's overwhelming grief at the death, that also seemed to have moved him to create a number of monumental religious works, this one being the most affecting. The golden urn in the foreground bears a faint Latin inscription dedicated to George, including his date of death. In stylistic terms, the art historian Gerald Ackerman has compared Bouguereau's religious works to "the masters of the high Renaissance[.] [Bouguereau] builds compositions out of the movement of strong, well rounded bodies, whose authoritative presence fills the canvases with energy." It is no coincidence that the position of Christ's head and shoulders echo that of Michelangelo's Vatican Pieta (1498-99) sculpture. Bouguereau also paid close attention to detail through his use of color: the rusty, drying blood on the white cloth in the foreground, the reddened eyes of the tearful Virgin, and the green tones of Christ's extremities in decay, all enhance the visual precision.

In 1870s France, religious painting was no longer the dominant genre it had been half a century previously, and the sharp, precise style of Neoclassicism was also under threat, from the advance of Impressionism; it is worth noting that this painting was composed four years after Monet's Impression, Sunrise (1872). However, Bouguereau was no captive of avant-garde fashion, and his personal identification with the Pietà theme allowed him to create a work transcending the cloying sentimentality for which he is sometimes criticized.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

The Birth of Venus

In Bouguereau's interpretation of a famous origin narrative from Roman mythology, Venus, the goddess of love and beauty, emerges from sea-foam standing on a shell, traversing the water to reach land. A flock of nymphs, tritons, and putti surround her in admiration while, in a take on the classic contrapposto stance of Venus Anadyomene from antiquity, the goddess accentuates the curves of her body in alternate directions, while adjusting her hair. Cool pastel colors evoke the dewy atmosphere of the marine world.

For this composition, Bouguereau drew inspiration from Renaissance masterworks such as Raphael's The Triumph of Galatea (c. 1514), with its encircling halo of cherubs, and Sandro Botticelli's seductive Birth of Venus (1486), both of which Bouguereau had studied in Italy during his Prix de Rome scholarship. Unlike Raphael and Botticelli's nudes, however, Bouguereau's Venus is captured with a refined naturalism indicating the new artistic tastes of the 1870s, without thereby foregoing Neoclassical artifice. As such, the work rises to the challenge of the late-19th-century Salon painter as described by T.J. Clark: to negotiate the flesh of a modern woman in Naturalist style while clinging to the Academic ideal of "the body as a sign, formal and generalized, meant for a token of composure and fulfillment." In its technical perfection, Bouguereau's Venus appears realistic, yet she remains displaced from individual identity, safely confined to the role of an ideal.

This proved to be a successful (and profitable) combination, and Bouguereau received great acclaim for this painting at the 1879 Salon. The strongly erotic tincture also hints at some of Bouguereau's more pragmatic methods for ensuring a buying audience for his work: whereas Botticelli's Venus conceals her bosom enticingly, Bouguereau's invites the viewer to inspect every section of her, unashamed of her nakedness and sensuality.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

A Young Girl Defending Herself against Eros

In this, one of Bouguereau's most popular works, a dark-haired maiden - based on one of his most popular models, who appears in several of his other works - pushes away a cherub seeking to pierce her breast with his arrow. The two are locked in a coquettish push-and-pull battle, and the young girl's resistance to Eros seems nominal at best. Her veil slips down to reveal a pert bosom, endowing her innocence with a semi-inadvertent sexuality, granting the painting a voyeuristic appeal.

This work is a good example of Bouguereau's erotically-charged classical and mythological tableaux, which sold particularly well with a new market of super-rich buyers in the United States, but which were often the subject of scorn from his Impressionist contemporaries. More than this, Bouguereau acquired the reputation amongst some painters and critics of a lecher, preoccupied with female nudes, and denigrating the legacy of his Renaissance progenitors such as Raphael by producing cheaply eroticized imitations of their work.

In stylistic and thematic terms however, the work is not as straightforwardly kitsch as it seemed to his detractors, the landscape based on contemporary France - probably that of the rural south, where Bouguereau had spent many of his formative years - and the painting is thus offering at least a superficially modernizing approach to its subject-matter. Moreover, Bouguereau's mastery of the human form, and of subtle tonal contrasts, is clearly evident.

Oil on canvas - Getty Center, Los Angeles

Dawn

Bouguereau's Dawn is the first in a series of four nude studies representing stages of the day, also including paintings entitled Dusk (1882), Night (1883), and Day (1884). In the inaugural work of the series, a nude female figure dances weightlessly on the surface of a pond, reaching over to smell a lily which she cradles gently in her arm. The cool tones of her skin echo the soft colors of early morning, while Bouguereau displays his mastery of dancer's poses by showing her balancing on the very skin of the water. Diaphanous drapery swirls around her, while her suspension in the air, and mirrored reflection, generate a supernatural effect.

Bouguereau returned to the marketable motif of the female nude throughout his career, arranging the body in various evocative and illustrative poses, often alluding to myth or literary history. Producing single-figure works such as Dawn allowed him to concentrate on the essential technical crafts of figure-painting: in this case, his mastery of line, and handling of subtle color-contrasts, contribute not only to the sinuous beauty of the figure but also to the atmospheric depiction of early morning. The model's fingers and toes are tinged with pink, a nod to the description of daybreak in Homer's Odyssey as "rosy-fingered dawn, the child of morning". Though the work is not based on any mythological or literary reference beyond this, Bouguereau always endowed his female nudes with a broad sense of classicism and the poetic.

Bouguereau's 'times-of-day' series was bought by his regular dealer Adolphe Goupil, who sold the four works in turn to various American collectors. The sale of the series reflects Bouguereau's success with Stateside as well as European art-markets, indicating his unparalleled critical and commercial acclaim during his lifetime.

Oil on canvas - Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama

The Nut Gatherers

Two young girls rest in a grassy clearing, pausing from the task of collecting hazelnuts. One holds a handful of nuts in front of her, while the other seems more interested in playing or sharing a secret. This work is an excellent example of Bouguereau's genre painting - work depicting scenes from everyday life - in which he generally favored the subject of women and girls in agricultural or domestic settings. His nut gatherers are dressed in plain peasant clothes, but appear exceptionally clean and content for members of the rural working poor.

By the early 1880s, the official tastes of the Paris Salon were shifting, and the movement of Naturalism was entering the artistic mainstream. Jules Bastien-Lepage's Hay Makers (1877), perhaps the great masterwork of rural Naturalist genre painting, showing two laborers resting after a day's exertion in the fields, had been displayed at the 1878 Salon to great acclaim, and Bouguereau was closely attentive to the shifting moods of the art market. Works such as Nut Gatherers respond to this shift, though his genre paintings display the same idealized polish as his Neoclassical work.

Criticisms of Bouguereau as overly sentimental can perhaps be traced to images such as The Nut Gatherers. Nevertheless, his later works are remarkable for their naturalistic precision, and successfully depict themes such as familial relations, quiet contemplation, and harmony with nature. Writing about the artist's view of peasant life for an exhibition catalogue, Mark Steven Walker praises the "heroic attention required to sustain such a vision of perfection in a less than perfect age." The image has certainly proved enduringly popular: sold to the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1952, The Nut Gatherers is cited by the Museum as one of their most popular works.

Oil on canvas - The Detroit Institute of Arts

The Young Shepherdess

In Bouguereau's 1885 painting The Young Shepherdess, a girl stands alone at the forefront of an expansive pasture, turning her body to face it with an air of propriety: suitably enough, as the title indicates her responsibility for the flock of sheep it contains. She looks back at the viewer with mild curiosity and friendliness, not averting her gaze.

Towards the end of his career, Bouguereau painted many rustic genre scenes that proved immensely popular with collectors, including various works on the "shepherdess" theme. At the Salon and through the endeavors of his dealer Adolphe Goupil, viewers were charmed by the artists' depictions of rural labor, especially when co-mingled with images of young girls at play. Bouguereau offered a more sentimental vision of peasant life than Realist painters such as Courbet and Millet, as indicated by works such as The Young Shepherdess. But again, his mastery of naturalistic figure painting cannot be questioned. In practical terms, the painting's protagonist is based on one of the Italian immigrant girls whom Bouguereau hired as models during family summers in La Rochelle. The girls received a monthly salary, participated in household chores, and ate meals with his family.

Art historians are divided on whether Bouguereau simply pandered to the market with his genre painting, or whether he elevated the peasantry with his love for their nobility and humility. John House describes Bouguereau's genre scenes as "broadly idealist ... treating his peasant women as if they were Raphael Madonnas." On the other hand, he lent distinctive personalities to some of his peasant girls, complicating his general commercializing attitude to the Naturalist style. In any case, Bouguereau's stance on the underclass never took a strong moral or sociological position like that of his contemporaries, and his politics - when directly expressed - tended towards conservatism.

Oil on canvas - San Diego Museum of Art

Biography of William-Adolphe Bouguereau

Childhood

William-Adolphe Bouguereau was born in 1825 in La Rochelle, a traditionally Protestant city on France's south-west coast. His father was a modestly successful wine and olive oil merchant and a Roman Catholic, while his mother was from a middle-class Calvinist family. Compromising on their children's religious education, they decided to raise their sons as Catholic and their daughters as Protestant. Bouguereau's upbringing was strict, but he developed a deep love for his seaside home and its local customs which endured throughout his life. At twelve, he was sent to live with his uncle, a Catholic priest, possibly to prepare the boy for a career in the Church. During this period, which Bouguereau later recalled as "the happiest time of my life," he was exposed to classical literature, outdoor excursions, and a new depth of familial affection.

Education and Early Training

A few years after moving to live with his uncle, Bouguereau was sent to the Catholic college in Pons, where he continued his religious and secular education. At Pons, Bouguereau was tutored in drawing by Louis Sage, a follower of the great Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, but his studies were interrupted by his father, who demanded that he join the family at their new home in Bordeaux, in south-east France. Here the young William-Adolphe became acquainted with Charles Marionneau, a local artist and historian who helped him to gain admission to the Municipal School of Painting and Drawing. Though he was under pressure to contribute to his father's business, Bouguereau thus resumed his artistic training, financing his education by creating hand-colored lithographs for food products. He excelled in this mercenary work, eventually saving enough to move to Paris, which he did in 1846, at the age of 20.

Following a recommendation from the Municipal School in Bordeaux, Bouguereau was invited to study under the accomplished Neoclassical painter François-Édouard Picot. Like the other students in Picot's studio, Bouguereau worked on the basic elements of figurative painting and drawing, using lithographs, plaster casts, and live models. Barely subsisting on his meager savings, he nevertheless gained admission to the prestigious École Royale des Beaux-Arts, whose curriculum focused on painting, anatomy, perspective, history, antiquity, and sculpture. Bouguereau's lofty ambition was to win the Grand Prix de Rome, a prize for outstanding young artists which included sponsored study at the French Academy in the Villa Medici in Rome. After two unsuccessful attempts, he achieved his goal with the grand historical painting Zenobia Found by Shepherds on the Banks of the Arax (1850), on a theme previously tackled by Nicolas Poussin. Bouguereau left for Rome in January 1851, spending the next three years refining his technical skills, and studying art collections, churches, architecture, and sculpture throughout the Italian peninsula. His scholarship ended in 1854, but instead of returning to Paris, he travelled back to his home town of La Rochelle.

Mature Period

Following his formative experiences in Italy, Bouguereau's career was defined by the ceaseless accumulation of praise and commissions, and by the annual exposure of his work at the Paris Salon. He stuck doggedly to the Neoclassical style in which he had been trained, and the display of his work at the Salons generated enormous interest from middle and upper-class patrons, and created opportunities to decorate state buildings and churches. In 1856, his prestige was further heightened by a commission from Emperor Napoleon III, for whom he completed the unashamedly propagandist work Napoleon III Visiting the Floods of Tarascon, showing the emperor's humanitarian visits to areas of the Rhône and Loire Valleys recently devastated by flooding. Demand for Bouguereau's work was consistent over this period, partly because of his contracts with two powerful art dealers, Paul Durand-Ruel and Adolphe Goupil. Indicating his pragmatic and commercialist approach to his work, Bouguereau began from around the 1860s to move beyond grand historical and classical subjects, creating quasi-Naturalist genre scenes in line with shifting artistic tastes. In practical terms however, he remained a staunch defender of tradition, and was instrumental, along with his Neoclassical peer Alexandre Cabanel, in ensuring that Édouard Manet's Déjeuner sur l'Herbe was rejected from the 1863 Paris Salon. This led to the establishment of the "Salon des Refusés", often seen as synonymous with the birth of avant-garde art.

In 1856, Bouguereau began a relationship with his 19-year-old model Nelly Monchablon, with whom he would have three children prior to their marriage in 1866, and another two thereafter. He maintained a luxurious family home and studio in the Montparnasse neighborhood of Paris, and in the summer would travel with his family to La Rochelle, where he often accepted local decorative commissions. Bouguereau kept a largely apolitical profile throughout his life, but twice became involved with politics outside of art, on both cases aligning himself with the forces of the French establishment. He enlisted in the National Guard during the revolution of 1848, and again in 1870, at the end of the Franco-Prussian War, prior to the brief seizure of power by the revolutionary Paris Commune (with which some of Bouguereau's peers, such as Gustave Courbet, associated themselves).

Late Period

While Bouguereau's professional life was one of uninterrupted success - he was granted lifetime membership of the Academy in 1876, and made a Commander of the Legion of Honor in 1885, the highest possible distinction for a living artist - his personal life was marked by tragedy. Three of his children died in infancy, and their mother Nelly died in 1877, events which inspired a series of somber religious paintings. Shortly after Nelly's death, however, Bouguereau began a relationship with another model, the American Elizabeth Jane Gardner - also a notable artist - whom he would marry in 1896, following a two-decade engagement (the couple were waiting for the death of William-Adolphe's mother, who disapproved of his remarrying). During this period Bouguereau's influence spread well beyond France, and he became active in artists' societies in Belgium, Austria, and Spain. Even in his advanced years, he worked prolifically, never abandoning his traditional methods of painting.

Over the last few decades of his life, Bouguereau also became an enthusiastic and influential teacher, mentoring both male and female artists in the Academic style. From 1872 onwards, he taught at the prestigious Académie Julian, and became known for advocating the training of female artists within that institution. Many of his pupils went on to achieve commercial and critical success, while outside of formal education he attracted countless admirers and imitators. When Bouguereau died in 1905 he was honored by grand funeral processions and memorials, both in Paris and La Rochelle. He is buried in Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris, next to Nelly and their children. Throughout his life he had remained intensely dedicated to his work, remarking: "each day I go to my studio full of joy; in the evening when obliged to stop because of darkness I can scarcely wait for the next morning to come ... if I cannot give myself to my dear painting I am miserable."

The Legacy of William-Adolphe Bouguereau

The popularity of Impressionism across the 20th century - not to mention the attitudes of the Impressionists to Bouguereau's work - partly explains Bouguereau's posthumous demise. More generally, the rise of avant-garde trends across the second half of the 19th century established a new paradigm whereby artists defined themselves against the Neoclassical standards of the Academy, meaning that Bouguereau's Academy-approved work was scorned by many of the most famous artists of the generation after him. He infamously reprimanded one of his students, Henri Matisse, for not being able to draw, while another, Edgar Degas, would describe a fussy, overwrought painting as "bouguerated". The same counter-cultural forces pushed back against the reputation of Bouguereau's Neoclassical contemporaries Alexandre Cabanel and Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier.

To be fair to his critics, Bouguereau clearly had a pragmatic attitude to the sentimental paintings which he produced with factory-line efficiency. These were paintings for the market, composed in response to a middle and upper-class clamor for images of stylized feminine beauty, titillating mythology, rustic country life, and childhood innocence. But Bouguereau's reputation as a bastion of bourgeois taste meant that the more progressive aspects of his life and work were overlooked. He had a passion for mentoring young artists at the Académie Julian, for example, and, unlike his contemporaries, enthusiastically encouraged the training of women artists.

Some renewed interest in Bouguereau's work emerged in the 1970s-80s, with major exhibitions in New York, Montreal, and Paris. Around the same time, various monographs and revisionary academic articles cast new light on his influence over 19th-century art in France and the United States. His paintings now command high prices at auction, and continue to circulate amongst private hands. It is fitting, given his mass appeal during his lifetime, that many of his works also appear on greetings cards, posters, and calendars, with images such as Cupid and Psyche (1890), better known as The First Kiss, flooding contemporary Western culture without the artist's name becoming any better known.

Influences and Connections

- Charles Marionneau

- Louis Sage

- Gustave Boulanger

- Jules Eugène Lenepveu

- Fritz Zuber-Buhler

- Johann Georg Mayer von Bremen

-

![Jean-Léon Gérôme]() Jean-Léon Gérôme

Jean-Léon Gérôme ![Leon Bonnat]() Leon Bonnat

Leon Bonnat- Alexandre Cabanel

- Ernest Meissonier

Useful Resources on William-Adolphe Bouguereau

-

![Through the Eyes of the Artist: William Bouguereau]() 32k viewsThrough the Eyes of the Artist: William BouguereauHudson Library & Historical Society / Overview of Bouguereau's biography with a discussion of his influences, followers, and legacy to the present day.

32k viewsThrough the Eyes of the Artist: William BouguereauHudson Library & Historical Society / Overview of Bouguereau's biography with a discussion of his influences, followers, and legacy to the present day. -

![A Young Girl Defending Herself Against Eros, William Adolphe Bouguereau]() 5k viewsA Young Girl Defending Herself Against Eros, William Adolphe BouguereauThe Getty Museum / Brief commentary on A Young Girl Defending Herself Against Eros (1880) at the J. Paul Getty Museum

5k viewsA Young Girl Defending Herself Against Eros, William Adolphe BouguereauThe Getty Museum / Brief commentary on A Young Girl Defending Herself Against Eros (1880) at the J. Paul Getty Museum -

![Cupid and Psyche, William Adolphe Bouguereau, 1825-1905]() 5k viewsCupid and Psyche, William Adolphe Bouguereau, 1825-1905Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery / Curatorial commentary on source material, eroticism, and technique in Cupid and Psyche (1889) from the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

5k viewsCupid and Psyche, William Adolphe Bouguereau, 1825-1905Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery / Curatorial commentary on source material, eroticism, and technique in Cupid and Psyche (1889) from the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery -

![Sotheby's Bouguereau and Courbet, Cupid and Psyche, New York 23 April 2010]() 17k viewsSotheby's Bouguereau and Courbet, Cupid and Psyche, New York 23 April 2010Comparison between two works by Bouguereau and Courbet on the same subject of Cupid and Psyche

17k viewsSotheby's Bouguereau and Courbet, Cupid and Psyche, New York 23 April 2010Comparison between two works by Bouguereau and Courbet on the same subject of Cupid and Psyche -

![Portland Art Museum, Artist Talk: Elizabeth Malaska, June 8, 2017]() 5k viewsPortland Art Museum, Artist Talk: Elizabeth Malaska, June 8, 2017Contemporary artist Elizabeth Malaska discusses Bouguereau's work Nature's Fan-Girl with Child (1881)

5k viewsPortland Art Museum, Artist Talk: Elizabeth Malaska, June 8, 2017Contemporary artist Elizabeth Malaska discusses Bouguereau's work Nature's Fan-Girl with Child (1881) -

![The San Diego Museum of Art, The Young Shepherdess]() 13k viewsThe San Diego Museum of Art, The Young ShepherdessCuratorial commentary on The Young Shepherdess (1885), a work included in the selection of artworks above

13k viewsThe San Diego Museum of Art, The Young ShepherdessCuratorial commentary on The Young Shepherdess (1885), a work included in the selection of artworks above -

![Glenn Lowry's Encounter with Nymphs and Satyr at the Clark]() 17k viewsGlenn Lowry's Encounter with Nymphs and Satyr at the ClarkBrief memoir of Glenn Lowry (current Director of the Museum of Modern Art) and his experience with Nymphs and Satyr (1873) at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute

17k viewsGlenn Lowry's Encounter with Nymphs and Satyr at the ClarkBrief memoir of Glenn Lowry (current Director of the Museum of Modern Art) and his experience with Nymphs and Satyr (1873) at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute - Discussion of Bouguereau's Nymphs and Satyr (1873)