Summary of The Venetian School

A celebratory lust for life, a thriving commercial port, and the influence of High Renaissance ideals of beauty and grandeur led artists in 15th and 16th century Venice to inject a bold new sumptuousness into the world of art. The Venetian School, which arose during this thriving cultural moment, breathed fresh life into the worlds of oil painting and architecture by combining inspiration from classical-oriented forebears with a new impetus toward lush color and a distinctly Venetian adoration of embellishment. With a slight nod toward the hedonistic, much of the artwork of this time, regardless of subject matter or content, was woven with the underlying message that the joyous act of being alive was to be considered with a sense of revelry and enjoyment.

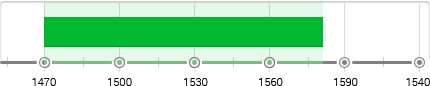

The Venetian School refers to the distinctive art that developed in Renaissance Venice beginning in the late 1400's, and which, led by the brothers Giovanni and Gentile Bellini, lasted until 1580. It's also called the Venetian Renaissance, and its style shared the Humanist values, the use of linear perspective, and naturalistic figurative treatments of Renaissance art in Florence and Rome. The second, related use of the term is the Venetian School of Painting, which beginning in the Early Renaissance lasted until the 18th century, and includes artists like Tiepolo, associated with the Rococo and Baroque movements, as well as Antonio Canaletto, known for his painting of Venetian cityscapes, and Francesco Guardi.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The Venetian School's groundbreaking emphasis on colorito, or using color to create forms, made it distinct from the Florentine Renaissance emphasis on disegno, or drawing the forms then filling in the color. This resulted in works of revolutionary dynamism, unparalleled richness, and distinct psychological expression.

- Artists in Venice painted primarily in oils, first on wood panels, then pioneering the use of canvas, which was better suited to the humid climate of the city, and emphasized the play of naturalistic light and atmosphere and dramatic, sometimes theatrical, human movement.

- Portraiture was revitalized during this time as artists sought a naturalistic treatment of their subjects that simultaneously conveyed their social importance. They focused not on the idealized role of a person, but their psychological complexity. These portraits also started utilizing more of the figure in the painting, rather than just the upper bust and head.

- New genres were born during this period including grand depictions of mythological narratives and the introduction of the female nude of its own accord rather than as a reflection of a religious, mythical, or historical tale. Eroticism began to appear, entwined in these new forms of subject matter, unconstrained by moralistic messages.

- A new architectural direction that married Classical influences alongside carved bas-relief and decidedly Venetian adornments became so popular that a whole industry of designing private residences cropped up in Venice.

Artworks and Artists of The Venetian School

Doge Leonardo Loredan

This commanding and compelling portrait depicts Leonardo Loredan, the Doge of Venice from 1501-1521, in a three-quarter pose. He is wearing his formal robes of state, including the corno ducal, or ducal hat, worn over a cap, with its traditional large buttons. The Doge is looking out from a balcony, his serious and calm gaze staring into the distance. The rich deep blue of the background contrasts with the sheen of the Doge's platinum robe intricately embroidered with gold and conveys a sense of serenity. A kind of majestic space is conveyed, its blue evoking heaven, and contributing to the sacredness of the character and role of its subject. Art historian John Pope-Hennessy who called Bellini, "the greatest fifteenth-century official portraitist," said of this particular work that, "the tendency towards ideality...enabled him to codify, with unwavering conviction, the official personality." The artist has signed his name in Latin on the small piece of paper painted in the foreground parapet.

Bellini pioneered Venetian portraiture and use of oils, both of which dominated Venetian painting. His approach became the distinctive Venetian style - emphasizing color contrasts, naturalistic light, and a focus on pattern and texture, as the fabrics seem to clothe a three-dimensional form, beckoning the viewer to touch them. Venetian artists did not aspire to the classical harmony and beauty of Renaissance Florence and Rome but rather to the ripple of light, the shimmer of color, and created a new, more intimate relationship to the viewer.

Oil on panel - The National Gallery, London

Feast of the Gods

This six by six foot canvas, large for its era, shows a feast where mythological figures have gathered, taken from a story by the Roman poet Ovid. Jupiter drinks wine in the center of the canvas, flanked by a dark eagle. A satyr with a wine jug on his head dances at the far left, and the god Mercury with his helmet and staff sits left of center with an empty cup at his feet. The nymph Lotis sleeps to the right while Priapus stealthily lifts her gown in an attempt to rape her. According to the story, the donkey on the left, associated with Silenus standing beside it, brayed and woke up Lotis, and Priapus was driven away by her and the group's ridicule. The tense dynamic is emphasized by the strategic use of rich color, as the darker browns, reds, and oranges move toward lighter touches of pink, yellow, and blue.

One of Bellini's later works, and one of the few with a mythological subject, the painting was completed in 1516 prior to his death. Subsequent scholarship has revealed that the painting was reworked a number of times. He reworked the canvas in 1514, repainting the figures of the two standing women with more revealing clothing, to suit his patron, the Duke of Ferrara who commissioned the work for his camerino, or private chamber. And on at least two occasions it was reworked by Dosso Dossi, and then Titian, who overpainted Dossi's work (except for the pheasant in the tree on the right) and repainted the landscape. The figures remain Bellini's. The Duke was to commission additional works from Titian and Dossi for the space, all of them depicting bacchanals, feasts of the gods, or nudes with an erotic content.

Bellini's work was innovative in pioneering the new "Feast of the Gods" type of scene, which became a common motif in subsequent art. As art historian George Holmes wrote, the room "constituted a large novelty in the European imagination...Secular life came into high art by the back door as the representation of the stories of the classical gods, in whom no one believed, but who, since they were not real gods, could be placed in embarrassing situations. The pictures in the Camerino were perhaps the crucial stage in this revolution."

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Young Woman

This portrait depicts a young woman in a three-quarters pose as she faces to the left, her gaze serious, her face unsmiling. She wears a red robe made of expensive fabric and lined with fur, which softly drapes her bare chest with right breast exposed. A sheer sash curves from her left shoulder, disappearing into the fold of fur just above her nipple, drawing the viewer's attention to the central eroticism of the piece. She is framed by thickly leaved branches.

The work's compelling sense of mystery led to its being titled "Laura" in the 1600's, referring both to the laurel branches behind her, and to the Italian poet Petrarch's famous 14th century sonnets to Laura. As art critic Jonathan Jones wrote, "his painting is amorous and poetic; there is a burden of imagery. But we can't decipher it. This woman lives, silently, intelligently, enigmatically, in her labyrinth of symbols."

Giorgione's innovation here was the creation of the first erotic portrait, and the approach became popular in Venetian art in the 1500s. The work influenced Titian's Flora (1516-1520), later artists like Caravaggio, as seen in his Boy with a Basket of Fruit (1593-1594), and 20th century artists like Pablo Picasso with his Nude, Green Leaves and Bust, a 1932 portrait of his lover, Marie-Therese.

Oil on canvas on wood - Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

The Tempest

This iconic masterpiece shows a soldier standing on the left gazing toward a nude woman, who breast-feeds an infant while looking toward the viewer. The work's title is taken from the storm gathering in the distance over a city, its pale buildings outlined against a turbulent sky of clouds and lightning. The surrounding landscape is a contrast of classical ruins and verdant growth, perhaps suggesting the fecundity of nature. A ravine that runs from the shadowed cleft of the lower left, up through the center of the canvas where a river darkens within the storm's shadow and a bridge horizontally transects the work, divides the pictorial plane. The composition is notably arranged, as the vertical movement of the ravine separates the two figures, while the horizontal bridge in the center also places the two figures within a separate space. Both the supposed relationship of the two figures and also its ambiguity are emphasized.

Traditionally, artists painted only images of the Madonna breast-feeding Jesus because when seen within the religious context, the exposed nudity found an acceptable justification. Giorgione's work was innovative in presenting the scene with an everyday nude woman, and because of her setting within a natural landscape, he may have been suggesting the perfect organic acceptability of the naked body to human life.

The meaning of this work has been much debated; some critics suggest it is based upon an unidentified classical poem, and others insist it is a still undeciphered allegory. Yet the sensuous color and naturalistic atmosphere make the painting compelling regardless, and revolutionary. Giorgione's innovations have been called "mood-landscapes," as he avoided narrative, and instead created a lyrical mood. His works became fundamental to the Venetian School influencing Titian, Tintoretto, Sebastiano del Piombo, Dosso Dossi, and even his teacher Giovanni Bellini. So much so that art historian Walter Pater was to call the Venetian painters "The School of Giorgione."

Oil on canvas - Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

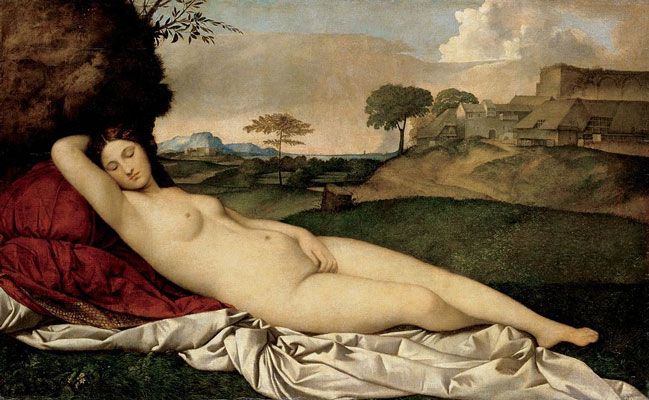

Sleeping Venus

This revolutionary painting depicts a female nude on a red pillow and ivory sheet, languidly looking toward the viewer within a naturally depicted landscape in subtle color gradations. The dark outcrop above her frames her head as the hills echo the undulations of her form. As a result, the composition creates a harmonious effect that emphasizes the beauty of the woman and the natural world. Her left hand rests upon her genital area in a Venus pudica pose, though any classical or allegorical references to the goddess have been left out. The work was completed the year that the young Giorgione died of the plague and Titian is credited with having finished the work, painting the red pillow and the farmhouse on the upper right. He also added a small figure of Cupid which restoration has, subsequently removed.

Giorgione was closely associated with the cultural and intellectual leaders of Venetian society. The scholar Aldus Manutius and the poet Pietro Bembo greatly influenced his developments in presenting the human figure as one in harmony with the landscape. The painting contributed to the burgeoning genres of the female nude and landscape painting. As art historian Giovanni Morelli wrote, "This'Venus' became the prototype, among painters of the Venetian School," for both its realism and its refinement.

Oil on canvas - Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany

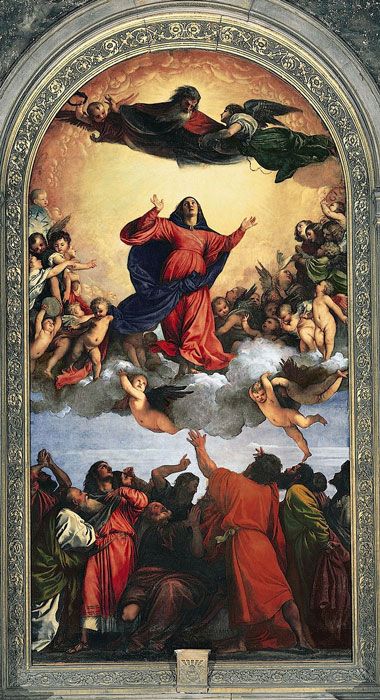

Assumption of Mary

This altarpiece depicts Mary as she rises, aloft on clouds in the center, arms raised and gazing toward heaven where God descends to meet her. Attending angels form a horizontal diagonal between the arches at the top of the painting, along with nude cherubim, their forms and gestures a swirl of excitement. In the lower third of the painting, the disciples look upward, their gestures signaling amazement.

This painting was innovative, even shocking for its time, with its emphasis upon movement and its energetic figurative treatment. The use of color and light innovatively animates the figures and their emotionally expressive dynamics. Additionally, Titian left out any elements of landscape and employed light as a compositional element.

This work, the largest altarpiece at that time in Venice, was commissioned by the Frari Church, and the initial response was described by Ludovico Dolce, an artist of the era, as "the oafish painters and the foolish masses, who until then had seen nothing but the dead and cold works...which were without movement or modeling, grossly defamed that picture. Then, as envy cooled and the truth slowly dawned on them, people began to marvel at the new style established in Venice by Titian."

Oil on panel - Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice

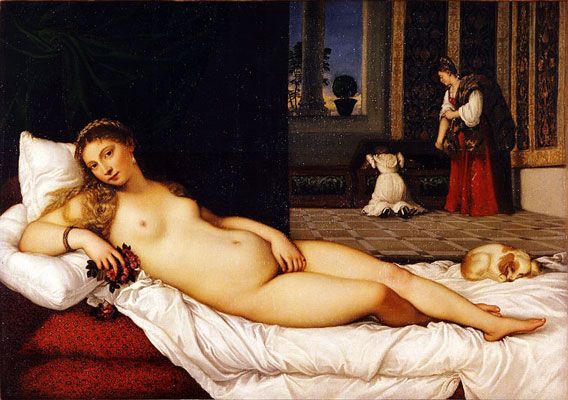

Venus of Urbino

This iconic work is one of the most famous and influential of nudes. It shows a woman as she reclines on a red lounge covered with white sheets, peering at the viewer with an intriguing gaze. Wearing only a gold, jewel encrusted bracelet on her right arm, she holds a flower, from which one red petal has fallen, and her left hand rests over her genitals in a classic pudenda pose. Above her feet, a small dog sleeps, while in the background in the upper right an older woman with robes over her shoulder watches a younger woman who kneels before an open cassone, or chest traditionally used for bridal garments. To the left of the two a window opens into a green luxuriant view.

The composition is divided into thirds, the upper half of the composition vertically divided between the black background behind the nude and the scene of the two women in the tiled room, so that the nude's reclining form fills the lower horizontal plane further emphasizing her languorous form. As a result, the painting separates public space - the hall where the servants work, and the window opening to the outer world - from private space, creating an effect of an intimate encounter with the nude, the implicit male gaze of the patron seeing her as if "for his eye's only."

The elements in the work from the cassoni to the dog, a traditional symbol of fidelity, have led to various interpretations. On the one hand, the work is said to have been a commission by Cardinal Ippolito de' Medici and the woman thought to be his mistress, or a courtesan. Alternately, it is said to have been commissioned by the Duke of Camerino for his wedding. As art critic Jonathan Jones wrote, "one of Titian's best known paintings, and probably his most provocative... the work feeds the ambiguity regarding the protagonist's social status by blurring generic boundaries. It is a pagan allegory, it is a private image that celebrates matrimony and, apparently, it is also a portrait."

The work also echoes Giorgione's Sleeping Venus (c. 1510-1511), and some scholars argue that both depict the same model shown on the same set of bed draping. But Titian has innovatively placed the nude within an indoor contemporary setting in order to focus on its unabashed eroticism. As art historian Charles Hope wrote, "It has yet to be shown that the most famous example of this genre, Titian's Venus of Urbino, is anything other than a representation of a beautiful nude woman on a bed, devoid of classical or even allegorical content."

This work influenced many later masterworks, as seen in Francisco Goya's The Nude Maja (1798-1800), Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres's La Grande Odalisque (1814), and Édouard Manet's Olympia (1863).

Oil on canvas - The Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Miracle of the Slave

This work shows a nude slave lying on the ground as he is about to be martyred by the crowd, and yet he is rescued by the intervention of Saint Mark, descending toward him. The intense but unusual color palette, as seen in its almost neon blue and pink, heighten both the chaotic ferocity of the scene, and the dramatic moment of the saint's appearance, making the slave invulnerable to the torture implements, which lie broken on the ground around him. The architecture evokes classical antiquity but departs from the proportional rationality of the Renaissance to create a theatrical scene, as seen in the figure peering down, perched somewhat precipitously on the right. What matters is the dynamic movement of the crowd, swirling around the center of the work, bisected by the vertical of the saint and the slave.

Tintoretto's innovations included spatial distortions as seen in the foreshortening of the descending saint and the use of a white undercoat to create a color palette that could evoke jarring human emotions. There is a story where as a student in Titian's workshop, he was expelled for his distortions of color and form that were meant to convey strong religious feeling.

The Scuola Grande di San Marco commissioned this work, along with three other paintings by Tintoretto, depicting the posthumous miracles of Saint Mark, Venice's patron saint. The series, which evolved toward a highly expressive, even sometimes surrealistic effect, had an influence on the development of Mannerism, and its emphasis on the dramatic moment to create awe-inducing emotion in the viewer also informed the Baroque period.

Oil on canvas - Gallery of the Academy of Florence, Venice

Feast in the House of Levi

This large painting depicts a festive and action-filled gathering that includes street entertainers, soldiers, and elegant aristocrats at a feast in the audience of Christ. Christ sits in the middle of the table, his importance reckoned by the beam of exquisitely rendered white light coming down from above. At the left end of the table, a red robed cardinal, bored and dissolute, turns away from Christ to watch the gathering, as does Judas, his face in shadow at the table's other end. The figures are precisely distinct, vivid with color and dramatic interaction. The magnificence of the architectural setting adds to the overall hedonistic effect, as linear perspective, most noticeable in the balustrade railings, draws the viewer's eye toward the center and creates a convincing depth so that the figures appear to inhabit a real space under the columns and their arched vaults, leading toward a view of the city in the background.

Stylistic innovations here include the artist's use of color gradations, rather than chiaroscuro, to convey the effects of light, retaining chromatic brilliance even in shadowed areas. The monumental scale of the work at 18 x 42 feet makes it one of the largest of 16th century paintings, which also contributes to the success of its trompe l'oeil effect in which it appears to be a life-sized, living and breathing scene amongst its surroundings. The subject matter, too, with its spectacle of contemporary life, was radically new. As art critic Jonathan Jones noted, "It does not seem to matter to Veronese which meal he is portraying. What he loves is the opportunity to show a diverse crowd of diners, waiters and entertainers enjoying a banquet. In reality he is portraying the high life of Venice, the city where he lived."

The church of Saints San Giovanni and Paolo commissioned this work to replace an earlier work by Titian, destroyed in a 1571 fire. Originally the work was called The Last Supper, but its depiction of the characters of Venetian society and street life made it questionable for religious authorities. As a result Veronese was called before the Inquisition on July 18, 1573. Rather than painting out the offending "buffoons, dogs, weapons" as defined by the Inquisition, the artist simply changed the title to "The Feast of Levi," a religious subject that allowed for the inclusion of questionable characters. Jonathan Jones finds him an early "hero of artistic freedom...a brave man who stood up to authority - and won."

Influencing later artists like Peter Paul Rubens, Veronese made a noted impact upon 19th century French painters, like Antoine Watteau, Delacroix, and Renoir. The art critic Théophile Gautier described him as, "the greatest colorist who ever lived," and Delacroix wrote, that Veronese "made light without violent contrasts, which we are always told is impossible, and maintained the strength of hue in shadow."

Oil on canvas - Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

Villa Almerico Capra Valmarana (La Rotonda)

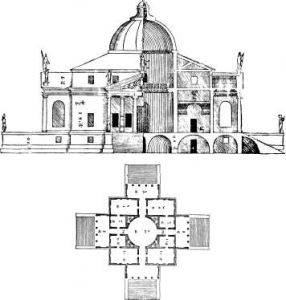

For this iconic hilltop villa, Palladio featured a central staircase, flanked by two statues on either end, leading up to a portico with Ionic columns that rise to a triangular pediment, where three classically inspired statues punctuate the vertical uplift. The four porticos and their staircases create a cross shape which intersects the square of the central building. As a result, approaching from any direction, this grand entrance meets the viewer, while, at the same time, each side gives the residents a magnificent view of the surrounding woodlands and meadows. Combining classical simplicity with a sense of grandeur, such homes perfectly conveyed the social standing of their owners.

The overall design, including the interior rooms, was mathematically proportioned according to Palladio's system defined in his Four Books of Architecture (1570). As Palladio wanted the building to be in harmony with the landscape, he included slight variations in his design. As art historian Charles Hind wrote, "His ideas of proportion and symmetry trickled down into the fundamental DNA of the building trade."

This work is part of the "City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villages of the Veneto," which includes both city buildings and villas designed by Palladio, designated as a World Heritage Site. Inspired by the Roman Pantheon, the building had what art critic Stephen Bayley called, "the greatest ever influence on taste," as aristocrats aspired to Palladian residences of classical grandeur. It's been said that this design "lead to a thousand homes," in Britain and the United States, including Lord Burlington's Chiswick House, Horace Walpole's Houghton Hall, Paxton House in Scotland, and Thomas Jefferson's Monticello. As architectural historian David Watkin wrote, La Rotonda, "has been valued for centuries as the quintessence of High Renaissance calm and harmony."

Stucco, brick, stone - Venice

Beginnings of The Venetian School

The Culture of Venice

While the Venetian School was informed by the innovations of Renaissance masters like Andrea Mantegna, Leonardo da Vinci, Donatello, and Michelangelo, its style reflected the roots of the very distinct culture and society of the Venice city-state. An emphasis on rich color permeated creation, bringing the atmosphere of the area and its people alive in a visual representation of the time. As art historian Evelyn March Phillipps wrote, "Venetian color, when it comes into its kingdom, speaks for a whole people, sensuous and of deep feeling, able for the first time to utter itself in art."

Venice was known throughout Italy as "the serene city" due to its prosperity. Because of its geographical location on the Adriatic Sea, Venice had become a vital hub for trade, linking the West to the East. As a result the city-state was worldly and cosmopolitan, emphasizing the pleasures and riches of life, rather than driven by religious dogma, and proud of its independence and the stability of its government. The first Doge or Duke to rule Venice was elected in 697, and subsequent rulers were also elected by the Great Council of Venice, a parliament made of aristocrats and wealthy merchants. Magnificence, entertaining spectacles, and lavish feasts marked by carnivals that went on for weeks, defined Venetian culture, and became part of its joyous artistic sensibility.

Unlike Florence and Rome, which were under the sway of the Catholic Church, Venice was primarily associated with the Byzantine Empire, centered in Constantinople that ruled Venice in the 6th and 7th centuries. As a result, Venetian art was strongly influenced by the Byzantine use of bright colors and gold in church mosaics and Venetian architecture was informed by the Byzantine use of domes, arches, and multi-colored stone, inspired in part by the Islamic architecture of the Middle East.

By the mid-1400s the city was a rising power in Italy, and Renaissance artists like Andrea Mantegna, Donatello, Andrea del Castagno, and Antonello da Messina visited or lived in Venice for extended periods of time. The Venetian School style synthesized Byzantine color and golden light with the Renaissance innovations of these artists.

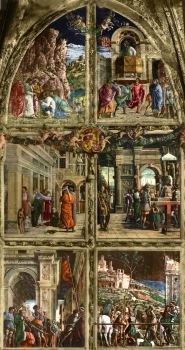

Andrea Mantegna

The artist Andrea Mantegna first introduced the linear perspective, naturalistic figurative treatment, and classical proportionality that defined Renaissance art to Venetian artists as he worked in nearby Padua, his native town, on his Stories of St. James (1448-1457). His work was to profoundly influence Jacopo Bellini who became one of the first Venetian artists to employ linear perspective, and taught the technique to his sons, Gentile and Giovanni, later leaders of the Venetian School. A lifelong artistic and familial connection developed, as Mantegna married one of Jacopo's daughters. Mantegna's influence can be seen in Giovanni Bellini's The Agony in the Garden (c. 1459-1465) referencing Mantegna's The Agony in the Garden (c. 1458-1460), both paintings based upon a drawing by Jacopo Bellini.

Antonello da Messina

Antonello da Messina worked in Venice from 1475-1476 and had a noted impact on Giovanni Bellini's adoption of oil painting and emphasis on portraiture. Credited with introducing oil painting to Italy by Giorgio Vasari, Antonello first encountered the art of the Northern European Renaissance while he was a student in Naples. As a result, his works were noted for their synthesis of Italian Renaissance and Northern European principles and influenced the development of the Venetian School's distinctive style.

Giovanni Bellini, “Father of Venetian Painting”

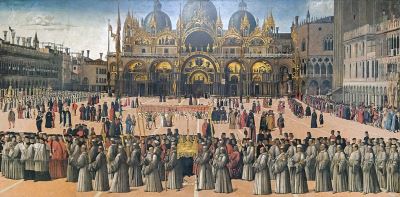

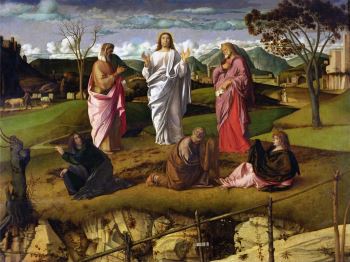

Pioneering oil painting in Venice, Giovanni Bellini has been called the "Father of Venetian painting." Both he and his older brother Gentile were renowned, making the Bellini family workshop the most popular and celebrated in Venice. Important early commissions by the Bellini brothers were primarily religious subjects like Gentile's Procession of the True Cross (1479) and Giovanni's work depicting the Deluge of Noah's Ark (c. 1470), now lost. Giovanni Bellini was particularly popular for his treatments of the Madonna and Child, a subject for which he had a deep affinity, and his depictions combined a kind of devotional gravity with a sense of charm and delight in the light and color of the world itself. However, it was Giovanni's emphasis on depicting natural light, and synthesizing Renaissance principles with Venetian color, that made him the leader of the Venetian School.

By the early 1480's Giovanni Bellini, shaking off the influence of Mantegna, had mastered oil painting as seen in his Transfiguration of Christ (c. 1480). He pioneered the Venetian School's emphasis on portraying natural light and atmosphere by employing color and tonal gradations. His Doge Leonardo Loredan (1501) established the Venetian School's stylistic treatment of portraiture and the importance of the genre in Venice. In later works, he turned to mythological subjects, like his Feast of the Gods (1504), which established a new genre of painting. Writing from Venice in 1506, Albrecht Dürer described Bellini as "the best painter of all." He was also a noted teacher, as both Giorgione and Titian, subsequent leaders of the movement, were trained in his workshop.

The Venetian School: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Portraiture

Giovanni Bellini was the first great portraitist among Venetian artists, as his Doge Leonardo Loredan (1501) created a compelling image that, while naturalistic and conveying the play of light and color, idealized the subject and his social role as leader of Venice. The much-acclaimed work fueled the demand for portraiture by aristocrats and wealthy merchants, who sought a naturalistic treatment that simultaneously conveyed their social importance.

Giorgione and Titian both pioneered new treatments of the portrait. Giorgione's Young Woman (1506) developed the new genre of the erotic portrait that was, subsequently, widely adopted. Titian extended the view of the subject to include most of the figure, as seen in his Portrait of Pope Paul III (c. 1553), and emphasized not the idealized role, but the psychological complexity of his subjects.

Paolo Veronese also painted noted portraits, as seen in his Portrait of a Man (c. 1576-1578) showing a full-length view of an aristocrat dressed in black standing against a pediment with columns. Jacopo Tintoretto was also known for his compelling self-portraits.

Mythological Subjects

Bellini pioneered the mythological subject in his Feast of the Gods (1504). Titian further developed the genre into depictions of bacchanal scenes such as his Bacchus and Ariadne (1522-1523), painted for the Duke of Ferrera's private chamber. Venetian patrons were particularly drawn to art based upon classical Greek myths, since such subjects, unconstrained by religious or moralistic messages, could be enjoyed for their eroticism and hedonism. Titian's work included a wide range of mythological subjects, as he created six large paintings for King Phillip II of Spain including his Danae (1549-1550), a woman seduced by Zeus disguised as sunlight, and his Venus and Adonis (c. 1552-1554) depicting the goddess and her mortal lover.

Mythological contexts also played a role in launching the genre of the female nude, as Giorgione's Sleeping Venus (1508), which pioneered the form. Titian further developed the subject by emphasizing an eroticism played toward the male gaze as in his Venus of Urbino (1534). Their titles placed both works within a mythological context, though their pictorial treatments elided any visual references to the goddess. Other works by Titian were to include such references as seen in his Venus and Cupid (c. 1550). The mythologizing impulse, so popular among the Venetians, also influenced their development of contemporary scenes as dramatic spectacles, as seen in Veronese's Feast in the House of Levi (1573) painted on a monumental scale, measuring eighteen by forty-three feet.

Venetian Architecture

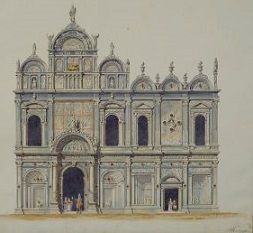

A coastal city noted for its system of canals, Venice had little solid ground upon which to build. As a result, many architectural projects involved redesigning buildings, often by creating new facades. The first architects of the Venetian Renaissance were the brothers Antonio and Tullio Lombardo, who rebuilt the Scuola di San Marco (c. 1490). Trained as sculptors, they carved the façade in relief to create an illusionistic perspective.

While Renaissance innovations via the work of Filippo Brunelleschi, Leon Battista Alberti, and Donato Bramante did influence Venetian architects, it was the Byzantine and Gothic tradition that continued to dominate architectural design. That changed in the 1500s, when the sculptor and artist Jacopo Sansovino moved to Venice after the 1527 Sack of Rome. Appointed chief architect of Venice in 1529, he was commissioned to design various public buildings in St. Mark's Square. His love of High Renaissance ideals led him to create a new style incorporating classical traditions alongside the Venetian love of lavish decoration. His masterpiece was the Biblioteca Marciana (1537-1587), the Library of Saint Mark's, praised by Andrea Palladio as the "best building since Antiquity."

The greatest and most influential of Venetian architects, Andrea Palladio, was known not only for his designs but his Il Quattro Libri dell' Architettura (The Four Books of Architecture) (1570), which included his architectural rules and concepts and was widely read throughout Europe. The Humanist scholar and architect Gian Giorgio Trissino was Palladio's lifelong mentor. Trissino, a friend of Leonardo da Vinci in Milan, was influenced by Leonardo's designs employing radial symmetry and his interest in the architectural principles of Vitruvius. As a result, Palladio employed Vitruvian classical elements and mathematical proportions but reinterpreted them toward simple designs that, using locally available and inexpensive construction materials, were easily reproducible. Though he designed the Venetian churches San Giorgio Maggiore (1565) and Il Redentore (1576), he was primarily known for his residential architecture. His country villas and city palazzos became the standard for aristocratic homes.

Later Developments - After The Venetian School

The Venetian School declined around 1580, in part due to the impact that the plague had upon the city as it lost a third of its population by 1581, and in part due to the deaths of the last living masters, Veronese and Tintoretto. Both artists' later works, emphasizing expressive movement rather than classical proportions and figurative naturalism, had some influence upon the development of the Mannerists that subsequently dominated Italy and spread throughout Europe.

However, the Venetian School's emphasis on color, light, and delight in sensory life, as seen in the works of Titian, also created a contrast with Mannerism's more cerebral approach, and informed the Baroque works of Caravaggio and Annibale Carracci. The Venetian School had an even greater influence beyond Venice, as kings and aristocrats from throughout Europe avidly collected the works. Artists in Antwerp, Madrid, Amsterdam, Paris, and London, including Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, Rembrandt, Poussin, and Velázquez, were widely influenced by Venetian art. The story goes that Rembrandt, when told as a young artist to visit Italy, replied that it wasn't necessary, because "it was easier to see Italian Renaissance art in Amsterdam than to travel from town to town in Italy itself."

Modern art is hardly imaginable without the influence of Titian, as critic Jonathan Jones noted, "The three most influential post-Renaissance painters, Velázquez, Rubens and Rembrandt, were devoted to Titian - Rembrandt modeled one of his own self-portraits on Titian's A Man with a Quilted Sleeve (c. 1510); Velázquez learned his luxurious style from Titians in the Spanish royal collection; Rubens copied many of his paintings." That influence has continued into the modern era as artists like Francis Bacon and Chris Ofili have noted his influence.

In architecture Palladio was equally influential, particularly in England where Christopher Wren, Elizabeth Wilbraham, Richard Boyle, and William Kent embraced his style. Inigo Jones, called "the father of British architecture," built the Queen's House (1613-1635), the first classical inspired building in England based upon Palladio's designs. As a result the British 17th century became dominanted by the "Palladian" style, and in the 18th century, Palladio's designs informed the architecture in the United States. Thomas Jefferson's design for his home at Monticello and for the U.S. Capitol building were predominantly influenced by Palladio and Palladio was named "Father of American architecture" in a 2010 decree by the U.S. Congress.

Well beyond the Renaissance era, the work of the Venetian School remained distinctive. As a result, the term "the Venetian School of Painting," continued to be used into the 18th century. Venetian artists like Giovanni Battista Tiepolo extended the distinctive style into both the Rococo and Baroque movements, with which he was associated. Other 18th century artists like Antonio Canaletto, known for his painting of Venetian cityscapes, and Francesco Guardi, are primarily discussed within the Venetian School of Painting. Guardi's work was later influential upon the French Impressionists.

Useful Resources on The Venetian School

-

![Venetian Renaissance Colore: A Material Thing]() 11k viewsVenetian Renaissance Colore: A Material ThingElena Phipps and Barbara Berrie / The Met

11k viewsVenetian Renaissance Colore: A Material ThingElena Phipps and Barbara Berrie / The Met -

![Meet the Masters of Renaissance Venice]() 7k viewsMeet the Masters of Renaissance VeniceRoyal Academy of Art

7k viewsMeet the Masters of Renaissance VeniceRoyal Academy of Art -

![Islamic Art and Culture in the Renaissance: The True Moor of Venice]() 230k viewsIslamic Art and Culture in the Renaissance: The True Moor of VeniceMichael Barry / The Met

230k viewsIslamic Art and Culture in the Renaissance: The True Moor of VeniceMichael Barry / The Met -

![The Impact of the Islamic World on Venetian Architecture]() 6k viewsThe Impact of the Islamic World on Venetian ArchitectureDeborah Howard / Cambridge Muslim College

6k viewsThe Impact of the Islamic World on Venetian ArchitectureDeborah Howard / Cambridge Muslim College

-

![Titian: Flesh - Art Documentary]() 284k viewsTitian: Flesh - Art Documentaryinfo

284k viewsTitian: Flesh - Art Documentaryinfo -

![The Renaissance Unchained: Bellini and oil paints]() 18k viewsThe Renaissance Unchained: Bellini and oil paintsOur PickBBC4

18k viewsThe Renaissance Unchained: Bellini and oil paintsOur PickBBC4 -

![Introduction: Veronese Magnificence in Renaissance Venice]() 25k viewsIntroduction: Veronese Magnificence in Renaissance VeniceNational Gallery

25k viewsIntroduction: Veronese Magnificence in Renaissance VeniceNational Gallery

-

![Giovanni Bellini: A pioneering Venetian artist]() 90k viewsGiovanni Bellini: A pioneering Venetian artistTalk by Caroline Campbell / National Gallery, London

90k viewsGiovanni Bellini: A pioneering Venetian artistTalk by Caroline Campbell / National Gallery, London -

![Venetian Painting Giorgione and Titian]() 4k viewsVenetian Painting Giorgione and TitianWith Peter Beal

4k viewsVenetian Painting Giorgione and TitianWith Peter Beal -

![Giorgione: Portrait of a Man]() 2k viewsGiorgione: Portrait of a ManTalk by Dr. John Marciari / San Diego Museum of Art

2k viewsGiorgione: Portrait of a ManTalk by Dr. John Marciari / San Diego Museum of Art -

![Titian: Painting the Myth of Ariadne and Bacchus]() 103k viewsTitian: Painting the Myth of Ariadne and BacchusTalk by Matthias Wivel / National Gallery, London

103k viewsTitian: Painting the Myth of Ariadne and BacchusTalk by Matthias Wivel / National Gallery, London -

![Paolo Veronese: a moment in the story of Alexander the Great]() 38k viewsPaolo Veronese: a moment in the story of Alexander the GreatTalk by Karly Allen / National Gallery

38k viewsPaolo Veronese: a moment in the story of Alexander the GreatTalk by Karly Allen / National Gallery -

![Veronese at the National Gallery]() 3k viewsVeronese at the National GalleryTalk by Waldemar Januszczak

3k viewsVeronese at the National GalleryTalk by Waldemar Januszczak