Summary of Benjamin West

The British colonists did not bring a strong art tradition with them to the shores of North America, but this did not stop Benjamin West, the first internationally recognized artist to hale from the New World. Self-taught in his early years, West became a prominent portrait painter in Philadelphia and New York before travelling to Europe to immerse himself in the Italian Old Masters and Greek and Roman art. There he took up the newly forming Neoclassical style and painted several large-scale history paintings that were wildly popular with the public.

Wrapped in a mythology of self-promotion, West was hugely influential for a new generation of American artists, including Gilbert Stuart and John Singleton Copley, that shaped the early Republic's visual identity. While his reputation languished with later critics and historians, West's eventual transition to Romanticism and embrace of current trends has prompted some scholars to consider West one of the first modern artists.

Accomplishments

- On the forefront of Neoclassicism, West felt that art should convey ideal virtues and moralizing tales to educate and civilize the larger public. Drawing on Classical visual and literary sources as well as Enlightenment era philosophy, Neoclassical art's emphasis on symmetry, stability, and nobility was an attempt to instill those same values in the citizenry.

- While painting largely for a European, specifically British, audience, West was careful to skirt the tensions between England and its New World colonies. While sensitive to English feelings, West still insisted on painting subjects taken from the New World, including Native Americans and colonial battles.

- West, though, was not content with telling long-ago tales and instead incorporated contemporary events and dress into his paintings. While criticized for flouting the rules of Neoclassicism espoused by the Royal Academy of London, West's wager paid off. His Death of General Wolfe was wildly popular and one of the most reproduced paintings of the time.

- West's penchant for innovation and his knack for knowing what was popular among audiences led him to embrace Romanticism at the end of his career. Emphasizing more dramatic story telling and evoking the sublime, West's later works still engaged the viewer but by appealing to their sense of emotion instead of reason.

The Life of Benjamin West

Romantic Poet Lord Byron was cruel about Benjamin West, describing him "Europe's worst dauber”. But West’s history painting had great appeal and he remained very influential in both Europe and North America.

Important Art by Benjamin West

Pylades and Orestes Brought as Victims before Iphigenia

West's journey towards epic history painting was a gradual one, which culminated in his first major canvas, whose subject was taken from the plays of the ancient Greek Euripides. The scene is set rather dramatically around an empty, central plinth on which the two defendants' fate rests. Pylades and Orestes, on the right, naked except for the sparse drapes covering their modesty, are accused of stealing the gold statue that can barely be seen in the top left of the frame. Iphigenia, dressed in white on the left, looks on at the pair as she prepares to deliver the death sentence. They are to be executed on the stone altar.

West said his "mind was full of Correggio" when he painted the work soon after he arrived in England from Italy. The high drama, rich color, and play of dark and light certainly recall the Italian Renaissance master, but West was also influenced by the history paintings of his contemporaries and friends Gavin Hamilton and Anton Raphael Mengs, who he studied with in Italy. Inspired by low relief sculpture of the Classical age, West highlights the foreground with bright colors and clear imagery. He also found inspiration in the frescoes of Raphael, his artistic hero.

This Neoclassical work was produced during the Enlightenment era, which promoted the value of civil society. As such, there was a moral argument for educating the people, and although West was not an intellectual, he agreed with these sentiments. For West, history painting's purpose was to "instruct the rising generation in honorable and virtues deeds." In 18th-century England, intimate knowledge of the history and culture of classical Rome would have been the preserve of the intellectual elite, but large works such as West's attempted to reach a wider audience.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Agrippina Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus

On this vast, almost 8-foot wide canvas, the viewer's eye is immediately drawn to the figural group in the center of the composition; Agrippina and other women and children are all shrouded in white, with their heads covered and eyes cast down, as they disembark from a boat. Agrippina, a granddaughter of the first Roman Emperor Augustus, clutches an urn, containing the ashes of her husband, and important military general, Germanicus, who died in Egypt under mysterious circumstances. The urn, while one of the smaller items in this busy work, is an important symbolic focal point in the painting, as it represents death (the ashes of Germanicus) but also the republican ideals and classical virtue that he fought for. The use of chiaroscuro throughout the composition further emphasizes the urn and the group of grieving women. In the foreground, women weep and bow to the arriving party as Roman soldiers keep watch; crowds observe from all around. In the background we see the masts of the boat and the classical architecture of Brindisi, an important port on the east coast of what is now southern Italy.

The subject came from Tacitus's History of Imperial Rome, and it was popular with Neoclassical history painters. It became one of West's most important works after it was commissioned by the Archbishop of York who, so pleased with it, arranged for West to show it to King George III. Increasingly, West took on the role of instructor, educating the public in the classics. As one art historian explained, "West's painting made the past immediate for mid-eighteenth-century Londoners and prompted contemplation of honor, resilience, and public virtue. We see in this work the essential ingredients of history painting: high seriousness, large-scale narratives of death and sacrifice drawn from well-known texts and histories, the incorporation of visual quotations, and meditations on the struggle between wickedness and virtue."

Oil on canvas - Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut

The Death of General Wolfe

In The Death of General Wolfe, West presents the dramatic tale of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, also known as the Battle of Quebec, which took place on September 13, 1759, a pivotal event in the French and Indian War. Two groups of soldiers and the Union Jack flag frame the General, as he lies dying, Christ-like, in the middle of the composition. The formal arrangement recalls traditional religious scenes such as The Lamentation or The Descent from the Cross. Instead of apostles, though, Wolfe is surrounded by high-ranking friends, one of whom unrealistically dabs at the General's blood-free chest with a white cloth. Despite its designation as a history painting, historians know that only one of the identifiable men in the foreground - flag bearer Lieutenant Brown - was actually present at Wolfe's death. In the foreground, a native American warrior kneels, embodying physiognomic Classical ideals while wearing traditional indigenous American dress, signaling both the Romantic notion of the "noble savage" but also reminding English viewers that Native Americans and colonials helped the British during the French and Indian War.

The muted, less-defined background creates a theatrical depth while focusing the viewer's attention on the scene at hand. In the distance, one sees the masts of the British fleet on the St. Lawrence River and a cloudscape formed by gunfire smoke adds considerable drama. On the left, the smoke begins to clear, revealing blue sky and a cathedral spire, symbolizing hope.

The work has been described as a "blockbuster" in its narrative abundance and as a "breakthrough" in its formal innovations. History painting did not at the time present current events, and the heroes would certainly not be wearing contemporary dress. West went against professional advice from Joshua Reynolds, who warned that everyday wear would diminish the subjects' heroism. West ignored him, arguing in line with Enlightenment thinking, "It is a topic that history will proudly record, and the same truth that guides the pen of the historian should govern the pencil of the artist."

Despite his stylistic rebellion, the piece was a success with the public, and its subsequent engraving by William Woollett found a huge commercial audience. One could find the print on private walls across Europe and America as well as on the sides of mugs. West went on to paint five more versions of this work, one of which King George III hung in his private collection at Buckingham Palace. West revolutionized what history painting would become in the hands of painters such as John Trumbull and John Singleton Copley. Art historian Loyd Grossman goes so far to argue, "If modernity is, in Michel Foucault's phase, 'the will to "heroize" the present,' then Wolfe is among the first great modern pieces."

Oil on canvas - National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

William Penn's Treaty with the Indians in 1683

William Penn's Treaty with the Indians in 1683 commemorates and allegorizes the moment when Quaker William Penn secured a land exchange with members of the Leni-Lenape (Delaware) tribe for the new colony of Pennsylvania. The Neoclassical style along with the strong verticals of the trees and houses paired with the horizontal arrangement of the figures creates a sense of harmony and stability, equanimity and calm. The portly Penn, dressed in brown, stands in the center of the composition with his arms outstretched, and he is surrounded by his fellow Quakers and Merchants. The Native Americans dominate the darker, right side of the painting and their gestures and postures draw the viewer's eye to the central action of the painting. Two merchants kneel and offer the tribal leader a bolt of cream-colored cloth. It was diplomatic custom at the time to follow the signing of a contract (notice the treaty in the hand of a gentleman on the left) with an exchange of goods. As one art historian explained, "The exchange between Penn and the Natives becomes, in West's painting a metaphor for fairness and mutual exchange between Old World and New."

Of course, what West masks and elides is the appalling and horrific ways in which colonists, and later the U.S. government, treated Native Americans. Colonial theorist Beth Fowkes Tobin writes, "West's presentation of Penn's 'justice and benevolence' towards the Indians is a masterpiece, not only aesthetically as an engaging painting, but politically as a powerful piece of propaganda that continues to work its magic on viewers today." Despite Penn's apparent magnanimity, the houses in the background along with the ships in the port speak to the dramatic and devastating changes that would come to the Native American way of life.

It is also possible that as an allegorical representation, West was also thinking of the present moment and the increasing tensions between the colonies and the British Crown (tensions ultimately leading to the long American Revolutionary War), perhaps hoping for a calm and balanced relationship as he depicted here.

Oil on canvas - Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia

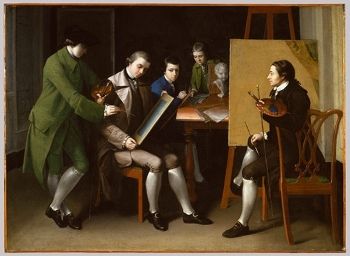

The West Family

Much quieter and more somber than his dramatic Neoclassical history paintings, The West Family presents an everyday, domestic scene. West's wife Elizabeth, dressed in white, holds their young son Benjamin Jr. on her lap while the older Raphael stands near, resting his arm on the chair and looking down at his brother. On the right, the artist's father, John, and his half-brother, Thomas, sit stoically in their chairs with their hands clasped in their laps. West himself stands behind them gazing at his family. The crisp detail and the triangular groupings of the figures present a stable, simple composition, but West does seem to depict some ambivalence: the brother seems uncomfortable as he stares out of the window, the palette is rather gloomy considering the happy context, and West, partly in shadow and at the edge of the composition, appears removed from the familial scene.

Art historian Jules Prown praised the artist for making the "quotidian universal" and likened it to the biblical scene of the nativity, but the work saw a mixed reception; while some praised its veneration of domestic happiness, others dismissed it as a piece of self promotion. Art historian Kate Retford addressed this ambivalence, "The attack on West reveals the fundamental tension at the heart of the elevation and sentimentalization of domestic virtues... One had to be seen as a loving father and kind husband to revive approbation and applause. However to advertise one's domestic credentials could be seen to seek that applause actively and to make it appear that all was being done for show."

Oil on canvas - Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut

Death on a Pale Horse

The dynamic and fiery Death on a Pale Horse was West's final major work. Completed just three years before the artist's death, the gruesome scene has much more electricity and violence than the measured subjects of his history paintings. The power of the piece's subject matter is emphasized by its vastness; the canvas measures more than twenty-five feet wide and over fourteen-feet high. The spiraling composition shows Death riding a white horse, descending on the earth with lightening bolts in his clenched fists as he rains terror. Behind him storm dragon-like creatures with eyes of fire, and beneath his horse's hooves one sees the carnage he has sowed. Strong men cower, while a woman and baby lie dead. Ghostly figures float strangely around the canvas.

The influence of Peter Paul Rubens is clear in this depiction of the scene from the New Testament Book of Revelation, and West returns to his Greek and Roman roots with the classical dress and armor. Importantly, though, West dispenses with Neoclassical, coherent storytelling and opts instead for emotion - dread, loss, terror, and the sublime. Art historian Jules Prown notes that Death on a Pale Horse is an important precursor to the likes of Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix. On seeing the work, art critic Thomas Hine wrote in 2018, "It is energetic and weird and barely coherent, like something from the Marvel universe. It is besotted with apocalypse, a wide-screen search for a cosmic conclusion. This wild West, who became so perfect an Englishman, might really have been the first American artist after all."

Oil on canvas - Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia

Biography of Benjamin West

Childhood

Born in 1738, Benjamin West was the youngest son of Sarah Person and John West, a Quaker who had married twice and had ten children. John West held a number of roles - cooper, tinsmith, and innkeeper among them, and Benjamin was born into humble surroundings near a New World settlement in Pennsylvania.

He had a happy childhood and became fascinated with art at an early age. His biographer, John Galt, wrote: "The first six years of Benjamin's life passed away in calm uniformity; leaving only the placid remembrance of enjoyment." He was encouraged to paint by his parents, drawing his infant niece asleep in her cradle when he was just six.

Galt wrote, "After some time the child happened to smile in its sleep, and its beauty attracted his attention. He looked at it with a pleasure which he had never before experienced, and observing some paper on a table, together with pens and red and black ink, he seized them with agitation, and endeavored to delineate a portrait: although at this period he had never seen an engraving or a picture." In the early settlement days of colonial America, West had no access to art - he reportedly fashioned his first paintbrush from his cat's fur and learnt about pigment from local Native Americans.

Education and Early Training

Despite his eventual success, West had no formal training or education, but his raw talent caught the eye of many patrons and mentors who would help him progress in his career. At the age of nine, he met English artist William Williams who introduced him to painting and lent him art books. By the age of 15, he was a prolific portrait painter and had gained local notoriety. When he met William Henry, a rich entrepreneur who was an advocate of history painting, West's fortune was set. Henry took him under his wing, telling him that his talents should not be wasted on portrait painting and that he should instead concentrate on historical subjects. Henry recommended Socrates as a subject, and with that West, at just the age of eighteen, produced the first secular history painting in America.

The Death of Socrates captured the attention of Dr. William Smith, the provost of the College of Philadelphia, who invited West to move nearby so that he could become the young artist's patron. Here West moved among the intelligentsia and took part in a special program of classical learning. In 1758, Smith introduced West to the world in one of his magazines, writing, "We are glad of the opportunity of making known...the name of so extraordinary a genius as Mr. West.... Without the assistance of any master, has acquired such a delicacy and correctness of expression in his paintings [that he will] become truly eminent in his profession."

Subsequently, West moved to New York where he made good money as a portrait painter, but he was unhappy. West told his biographer that the institutions of the college and library in Philadelphia and "the strict moral and political respectability" of the first settlers had formed a learned and sophisticated community, but he found the society of New York "wholly devoted to mercantile pursuits" and "less intelligent in matters of taste and knowledge" than his old friends. The nascent capitalist pursuits of New York were distasteful to a man used to valuing the cultural and aesthetic aspects of life.

Mature Period

The year 1760 marked another turning point for the ambitious and serious-minded young artist when he travelled to Italy to learn from the Old Masters, one of the first American-born artists to do so. The influence of antiquity that he saw in Europe would have untold influence on his work and, in turn, the subsequent neo-classicism that dominated American culture. West cultivated an obsession with sculpture, which provided, in his words, the truest example of "genius directed by philosophy."

John Galt described West's 1760 encounter with the celebrated marble sculpture the Apollo Belvedere in the Vatican with a story that became mythologized in West's own life. The statue was kept in a case with doors which were opened for visitors. Galt wrote, "When the keeper threw open the doors, the artist felt himself surprised with a sudden recollection altogether different from the gratification which he had expected; and without being aware of the force of what he said, exclaimed, 'My God, how like it is to a young Mohawk warrior.'"

With this declaration, West had offended the Italians in his party; they were upset at the Apollo's comparison with a people they considered to be savage. West defended his remark, saying, "I have seen them often, standing in that very attitude, and pursuing, with an intense eye, the arrow which they had just discharged from the bow."

West was so overcome by what he saw in Rome, he fell ill and had to return to the coast in Tuscany to recover. West, writing about himself in the third person, said, "This sudden a climax from the cities of America, where he saw no productions in painting...to the City of Rome the seat of art and taste, had so forcible an impression on his feeling that he was under the necessity of leaving Rome in a few weeks, by the advice of his physician and friends, or it would put a period to his life." The description is in line with the symptoms of what was called Florence, or Stendahl, Syndrome, a psychosomatic disorder that causes rapid heartbeat, dizziness, fainting, and confusion when an individual is exposed to an experience of great personal significance, particularly when viewing art.

When West returned to Rome, he studied with the influential 18th-century German art historian Johann Joachim Wincklemann, who would inspire a classical revival in all of Europe, and met painters Anton Raphael Mengs, Gavin Hamilton, and Angelica Kauffman. Under Wincklemann's tutelage, the artists looked to the art of classical Greece and Rome to give vision to the political ideals of the Enlightenment era. West spent his time catching up on his lack of artistic training, sketching the Italian masters and making studies from classical friezes and sculpture. He toured Florence, Bologna, Parma, and Venice and rose to fame. West's studies in Italy placed him in the foreground of the development of Neoclassicism, as his Agrippina Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus preceded Jacques-Louis David's Oath of the Horatii (1784).

While in Italy, West again became ill with a dangerous bout of osteomyelitis which saw him confined to his Florence room for six months, but the dedicated artist continued to paint from his bed, having a special frame made to allow him to do so.

His trip to London in 1763 was never meant to be permanent as he just wanted to visit the home of his ancestors, but after finding success in history painting in England, he never returned to Italy or America. A year later, he married the Philadelphian Elizabeth Shewell at a service in central London's St. Martin in the Fields. He named his firstborn son Raphael, after the painter he admired above all others. He even produced a painting of his wife and child in the reverse pose of Raphael's Madonna della Sedia (1514).

By 1770, West had become one of the most successful artists in London, and it was in this year that he produced his best known work, The Death of General Wolfe, an epic history painting depicting the Battle of Quebec. The popular work had a profound effect on the art world and changed the way artists would produce history paintings.

Art critic Jules David Prown, wrote, "The history paintings that West produced after settling in England embodied the intellectual and moral values as well as the visual experience and information he had garnered in Italy." His purpose was to combine "ethical lessons" learned from the ancients with Christian morality. "Antiquity provided standards of reason, intellect, morality, and dignity; religion warmed these with emotion and piety," wrote Prown.

In 1768, West was made a charter member of the Royal Academy of Arts, and when its founder and president Joshua Reynolds died in 1772, West was made president. Four years later, West was made historical painter to the king, for which he was paid £1,000 a year. King George III adorned the Warm Room in Buckingham Palace with no fewer than seven of West's history paintings, enormous canvases that dominated the walls.

While West managed to place himself firmly within the British institution thanks to his friendship with the King, he used his New World origins to create a mythology around himself. Art historian Vivien Green Fryd explains that he exploited his colonial background to present himself as "exotic and unique, suggesting that as a native-born American, he had the authority to record the New World's history."

18th-century London was an important locus in the developing commercial art market, and West became adept at working it. He was often included in exhibitions, showing more paintings than his contemporaries, and he took advantage of the era's new mass communications and mechanical reproduction to grow a fanbase, while simultaneously building his relationships with rich and powerful patrons. As art historian David Solkin wrote, "London can be identified as one of the first metropolitan art centers where the various commercial, cultural, and institutional mechanisms characteristic of a distinctively modern art work came into being." During this time, many oil paintings were reproduced as mezzotints, and a fashion for cheap prints emerged, making the paintings available to an even larger audience.

Later Years and Death

West's role as a royal painter also meant he was at George III's mercy. The King demanded paintings that expressed the style and nobility of the court, but West's position was conflicted; while he made a successful career in England catering to royal patrons, he was unable to follow his dreams of pursuing certain scenes from American history. When the colonies gained independence in 1783, he felt unable to produce the heroic portraits of George Washington as he wished, although he did continue to make smaller works, studies of Native Americans who primarily acted as historical, or ethnographic, subjects but also held an important symbolic role. They represented America as "an idyllic state of nature, an uncorrupted place", according to historian John Higham.

As the political landscape changed, West prudently reduced his body of history painting. Prown explains, "Improvement in civic behavior implied change, and change could mean revolution." The artist continued to have a long and successful career, later focusing on medieval and religious subjects, becoming known as the "Raphael of America."

West experienced periods of ill health and suffered from chronic rheumatism, gout, and a bone infection during his lifetime. But despite these ailments, he led a long and happy life. West's private life was like an open book, Helmut Von Erffa art historian, wrote, "No scandals were ever reported of him even in this century of scandals." His wife said that in the forty years they were married, she had only once seen him intoxicated and had never seen him "in a passion." The painter could at best be serious-minded and at worst pompous. He was reported to have turned down a knighthood from the King, refusing it on the ground that he would better be suited the higher honor of a baronetcy.

He remained close friends with King George III, and on the King's death in 1820 was reported to have said, "I have lost the best friend I have had in my life." West died a few months later at his central London home at the age of 81. His biographer John Galt wrote, "Mr. West expired without a struggle.... On the 29th he was interred with great funeral pomp." He was buried at St. Paul's Cathedral, the mother church of London and also the final resting place of Joshua Reynolds.

The Legacy of Benjamin West

Prown said, "[West] was perhaps the first great American expatriate, anticipating Henry James and John Singer Sargent by a century." The reputation of the man who became known as "the father of modern art" took a hammering in the years after his death, with critic Walter Thornbury calling him "The Monarch of Mediocrity" and Lord Byron damningly referring to him as "Europe's worst dauber, Britain's best." Prown, though, defended him, explaining "Few artists were as long-lived, productive, influential and professionally in their own time as West. And few suffered such a precipitous and, in my opinion, undeserved post‐mortem decline in reputation."

Despite the protestations of some, others placed him on the forefront of modernism. Loyd Grossman, author of Benjamin West and the Struggle to be Modern (2015), wrote, "West remains among the most neglected and misunderstood of Britain's great eighteenth-century artists, lacking the social bite of Hogarth, the bravura of Reynolds or the easy elegance of Gainsborough...yet he was extraordinarily in tune with the artistic and intellectual currents that swirled through his turbulent times." West, he added, "was in the vanguard that created Neoclassicism and Romanticism."

West believed he had a moral duty to present truth through his art, and he took on students from both the United States and England. His influence was seen through three generations of American artists, including Charles Willson Peale, his son Rembrandt Peale, and Gilbert Stuart - the artist responsible for the portrait of George Washington that graces the dollar bill. Willson Peale was the first of the artist's pupils to produce classically influenced work in his portraiture. Similarly, John Singleton Copley referenced antique marbles in his work and studied the classics in Rome, after West's recommendations. With these artists, it is clear that West had, in Prown's words, an "unparalleled influence on the development of American art for over half a century."

Influences and Connections

-

![Anton Raphael Mengs]() Anton Raphael Mengs

Anton Raphael Mengs -

![Joshua Reynolds]() Joshua Reynolds

Joshua Reynolds - Gavin Hamilton

-

![Gilbert Stuart]() Gilbert Stuart

Gilbert Stuart -

![John Trumbull]() John Trumbull

John Trumbull -

![John Singleton Copley]() John Singleton Copley

John Singleton Copley - Charles Wilson Peale

- Ralph Earle

- Thomas Godfrey

- Francis Hopkinson

- Jacob Duche

Useful Resources on Benjamin West

- Benjamin West and the Death of a StagBy Duncan Thompson

- British Art and the Seven Years' War: Allegiance and AutonomyBy Douglas Fordham

- Benjamin West and the Struggle to be ModernOur PickBy Loyd Grossman

- The Life, Studies, and Works of Benjamin WestOur PickBy John Galt

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI