Summary of Edmonia Lewis

Edmonia Lewis' sculptures depicted popular subject matter for 19th century American audiences. Carefully crafted marble portrayals of Native American literary characters, African emancipation subjects, and other exotic figures launched her into the international spotlight. Lewis' identity as a female artist of mixed race who lived and worked in Rome also helped propel her to fame in America, which had endured a four-year Civil War over slavery and was struggling through a new wave of racial tensions. Known for her determined approach to self-promotion, Lewis very straightforwardly used gendered and racial status in the marketing and selling of her sculptures.

Accomplishments

- It was quite exceptional for a woman to pursue a career in art in the 19th century, especially in the more labor-intensive medium of stone carving. As a woman of color, Edmonia Lewis' attainment of fine art training and achievement as a professional sculptor makes her a singularly important figure.

- Her sculptures were created in a Neoclassical style, but her most important creations possessed Lewis's particular emphasis on subjects with social significance. American art collectors who agreed with the abolition of slavery and enjoyed popular literature about Native American subjects were enthusiastic about owning Lewis' sculptures.

- Lewis' portrayal of female African and Native American figures was unusual in that they were given Caucasian facial features. Doing this enabled Lewis to create a kind of psychological distance between herself as a mixed-race artist and the minority subjects of her art, so that the viewer could not imagine the artist using herself as a model. While she used her own status as a mixed-race artist to help promote her work, she otherwise maintained a kind of visual separation from the female subjects she portrayed.

Important Art by Edmonia Lewis

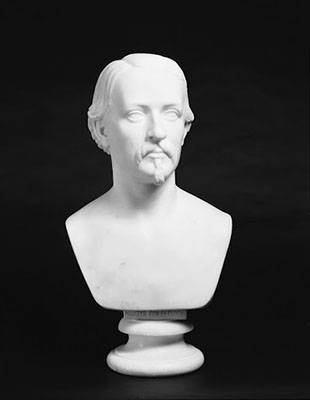

Bust of Robert Gould Shaw

This bust represents Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the first commander of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, who died in the assault on Fort Wagner in South Carolina in July 1863.

It is a traditional 19th century commemorative bust, and the first commercial success for Lewis who chose to represent only the face of the man leaving the bottom portion uncarved. The artist based the portrait on a photograph that she borrowed from Lydia Marie Child, an abolitionist who encouraged much of Lewis' early work in sculpture. Despite Child's concerns that the inexperienced Lewis might not strike an accurate enough likeness to satisfy her Bostonian audience, the artist created a delicate, accurate representation of the Colonel. Child had to concede that the bust was a success. Shaw's family awarded permission to Lewis to execute 100 plaster reproductions. The sales of these reproductions funded Lewis' eventual relocation to Rome, Italy.

Museum of African American History, Boston and Nantucket

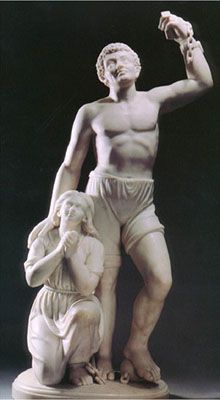

Forever Free

This life-size sculpture depicts a young African American couple at the moment of emancipation. The man is represented standing with his left arm raised, defiantly displaying his broken chain. His left foot rests on the ball connected to the chain. He is bare-chested and his curly hair alludes to his African origin. Kneeling at his side, a woman is joining her hands in prayer. She is fully clothed and her features are much more European. She has long, straight hair.

Originally titled "The Morning of Liberty," this sculpture celebrates the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation that stipulates that "all persons held as slaves" within the rebellious states "shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free." Although female figures in Neoclassical portrayals are often nude or semi-nude, Lewis dresses the woman completely here, and challenges the sexual connotation associated with female slaves. Many scholars have criticized the "whiteness" and the submissive position of the woman, but for Lewis, her figure here is a freed woman performing in her gendered role as defined by 19th century Victorian values. As art history professor Kirsten P. Buick explains, Lewis's representation of a freed couple falls into the Victorian Cult of Womanhood in which a woman signifies submission, piety, and virtue, while a man enacts the roles of being both protective and triumphant.

The fact that the female figure has no specifically African features has been considered by scholars as a way for Lewis to distance herself from her subjects to give her work more credibility in a white-dominated art world. Buick asserts that the artist did not want her public to read her works as too closely tied to their maker. If they possess more Caucasian features, they are more readily relatable for the intended consumer: a white, wealthy art collector of the Victorian era, already conditioned to expect this stylization through exposure to other, similar Neoclassical statuary.

Howard University Gallery, Washington DC

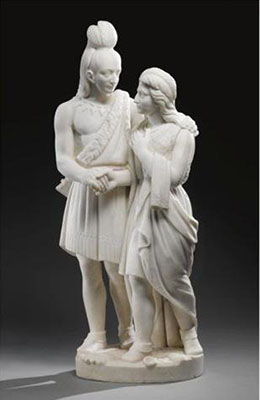

The Marriage of Hiawatha

This sculpture is based on the 1855 poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Song of Hiawatha. This fictional tale draws from Native American legends and tells the story of Hiawatha, an Indian Ojibwe warrior. He falls in love with Minehaha, a woman from the rival tribe of the Dakotahs, and marries her. While holding Minehaha's hand in his, Hiawatha puts his other hand on her shoulder. She places her other hand on her heart. The ethnicity of the couple is exclusively indicated by their generalized Native American dress. Minehaha's necklace is a direct allusion to Longfellow's description of it as a symbol of their romantic union. While Hiawatha's facial features appear vaguely Native American, Minehaha's appear to be entirely Caucasian and therefore Neoclassical in style.

Lewis emphasizes the reserve, reverence, and dignity of a poetic love described in Longfellow's poem. Longtime Lewis historian Marilyn Richardson interprets the sculpture as a reference to an easily accessible subject in Lewis' Roman life - that of Cupid and Psyche. A very wide array of ancient sculpture portraying mythological subjects was available for tourists and artists to view and study in museums as well as public and private collections in the Eternal City. For Lewis, an elevation of the once savage 'Indians' Hiawatha and Minehaha to more noble levels was a development worth pictorializing. True to Victorian sensibilities of the time, Hiawatha expresses a protective, dominant persona that protects the more diminutive Minehaha.

Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Montgomery, Alabama

Hagar

This sculpture depicts Hagar, the servant of the matriarch Sarah in the Bible. As Sarah is barren, she offers Hagar to Abraham so that he can fulfill God's promise to be the father of many nations. However, when Hagar becomes pregnant, Sarah grows very irritated with her and, given full power by Abraham, treats Hagar very harshly. Beaten, pregnant, and humiliated, Hagar runs away to the wilderness. An angel appears and instructs her to return to her master and mistress to accomplish God's will. Hagar abides, returns to Sarah's household and gives birth to Ishmael. God also gives ninety-year old Sarah her own son, Isaac. Tensions between the two women do not dissipate, however. Sarah becomes infuriated when she later sees Ishmael mocking her own son. Hagar is ultimately sent away again to wander, accompanied by Ishmael.

While Hagar is supposed to be an Egyptian, she is highly classicized in this sculpture. Her facial features are Caucasian and her hair is long and straight. She has an elegantly draped tunic that uncovers one of her breasts. She stands and appears to pray, with her hands together. Her expression is stern. At her feet, there is an overturned jug, alluding to the point in the Biblical narrative when she is searching for water in the desert and the angel appears.

A devout Catholic, Lewis uses Hagar as a metaphor for all African American female slaves and their sustenance through faith. Abused by her masters, Hagar is then expelled from the household with her child and no other resources. Her uncovered breast refers to the sexual assault, and emphasizes her vulnerability, as rape was a common crime committed upon female slaves. In addition to these abuses, historian Kristen Buick interprets Hagar as a representation of the despair and dismantling of the African-American family under slavery. By illustrating Hagar's fortitude and faith in God's direction as she wanders in the wilderness, Lewis restores dignity to Hagar as a woman and as a mother.

Smithsonian American Art Museum

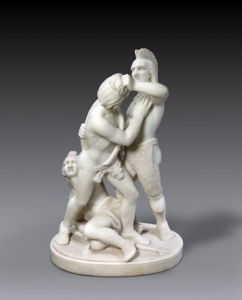

Poor Cupid, or Love Ensnared

This small sculpture depicts Cupid caught in a trap while picking a rose. The god is portrayed here as a chubby, winged boy with curly long hair. He carries his classic attributes of the quiver and bow. His facial features are very adult in form. His wrist still inserted into the bow gives a anecdotal tone to the sculpture. The title is both ironic and metaphorical.

This sculpture was probably intended to appeal to the popular taste of visiting American tourists who might have wanted a memento of all of the pagan art on display in Rome. Cupid's attitude is playful and endearing. There are no other known copies of this work, to date.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

The Death of Cleopatra

This work is considered to be Lewis' masterpiece. Carved in 1876, this massive, two-ton sculpture represents Cleopatra at the moment of her death. The legendary, exotic Egyptian queen committed suicide to avoid being taken as prisoner after the defeat of her armies in a decisive battle with Octavian, who became Augustus Caesar, first leader of the Imperial age of Rome. Her method of suicide was to allow an extremely poisonous asp to bite her. Lewis adorns Cleopatra in her usual attributes of crown, necklace and bracelets, but dresses her in a more or less Neoclassical garment, which alternately drapes her shoulder and waist and uncovers one breast. The throne appears to have been finely sculpted with many details on the back side. Two identical pharaonic heads decorate the arms of the chair.

This sculpture is unusual in the canon of Neoclassical portrayals of Cleopatra, as it somewhat inelegantly emphasizes the queen slumped in death. Slouched in her throne, her head thrown back, and still holding the snake in her right hand, Cleopatra's position is highly dramatic. Her face - lacking any Africanized features which would have pointed to the current, progressive acceptance of being Egyptian as also being Black - remains passive, however.

This monumental sculpture was praised by contemporary critics for its daring expressivity. It commanded a great deal of attention in its debut for the American public, deemed the 'most important sculpture in the American section' in the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. It was given pride of place, located in the highly desirable rotunda exhibition space. Despite Black Americans' intentions to have heightened national visibility in this exposition, Lewis was one of only two African American artists to be ultimately included. Her treatment of a subject that was already popular among Neoclassical sculptors remains unique, and is the subject of much scholarly focus.

Depictions of Cleopatra in death more commonly depicted her romanticized demise while surrounded by African slaves. Lewis portrays the queen alone in her actions immediately preceding her death. For visual source material, Lewis may have relied upon coins struck during the queen's reign, (undoubtedly visible in Roman collections), which depicted Cleopatra with a straight, narrow-nosed profile. This may have been due to the queen's historically accepted but ultimately unproven partial ancestry as Greek or Roman.

Abolitionists in the 19th century championed Egypt as Black Africa and imbued Cleopatra with "evidence of African accomplishment and capability of leadership," as Susanna W. Gold writes. Driven by an inner vision, Lewis' work in this perspective slightly differs from the abolitionists' vision, in that her Cleopatra - as she became a center point of the Centennial Exposition of 1876 - may instead be a kind of personification of Emancipation and its immediate aftereffects, which were for Black Americans rapidly proving to be dismal.

Alternately, Cleopatra was a complex figure who could also be seen as a power-mad, sexually controlling Black woman. According to Kristen Buick, by distancing the Queen from established conventions and suggesting a less ethnic identity, Lewis may have wished to separate all black women from this unusual conception of the Queen. The abundance of details, the exposure of the body and the unique face force the viewer to consider the figure as Cleopatra only. Lewis' forces the viewer to confront the death of a singular figure removed from us in history, and so she cannot be used as an allegory or a self-portrait. This strategy enabled Lewis to keep her identity as a women artist of mixed race separate from the queen historically framed as a woman of ethnicity.

For several years, Lewis' sculpture of Cleopatra literally disappeared from view as an important work by an American woman artist of color. Unsold after the Exposition, it was placed in storage. It was later sold to a gambler who elected to use the sculpture as a centerpiece in a large burial monument for a prized racehorse named Cleopatra, placed in the grandstand of Chicago's Forest Park racetrack. It eventually wound up outdoors in a construction storage yard elsewhere in Chicago. The sculpture remained unprotected from the elements for a long time. A local Boy Scout troop attempted to 'improve' the sculpture by painting it. In 1985, a local dentist purchased the work and stored it in the Forest Park Mall. Once the dentist contacted the Metropolitan Museum of Art and a specialist on the career and work of Edmonia Lewis was notified, the sculpture was finally properly recognized and donated to the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in 1994.

In a number of ways, the interpretation and object history of this seminal work parallels the story of an extremely unusual artist of 19th century America.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

Biography of Edmonia Lewis

Childhood

Information about Edmonia Lewis' birth and early origins is vague and contradictory, in large part due to the artist's own ambitions. When asked, she would often create different narratives about her early life in order to enliven her beginnings as an artist. When she applied for a passport in 1865, she stated that she was born "on or about" July 4, 1844 in Greenbush (now Rensselaer), NY.

Her father, Samuel Lewis, was a free African-American possibly from the West Indies who worked as a gentleman's servant. Her Canadian mother Catherine was the daughter of African and Ojibwe (Chippewa) parents. According to the artist, she was named "Wildfire" at birth. Because her mother's parentage was not entirely Native American, neither Lewis nor her mother or brother were permitted to live on the Ojibwe reservation.

By the time Lewis was nine, both of her parents were deceased. She and her older half-brother Samuel or "Sunrise" were then raised by their maternal aunts in upstate New York near the Niagara Falls tourist center. She would later tell interviewers that she lived a nomadic life with her mother's tribe, fishing and hunting along the northern shore of Lake Ontario. To support themselves, Lewis reported, the tribe made baskets and quill-work to sell to tourists at Niagara Falls.

Early Training and Work

Lewis' brother Samuel sponsored her forays into education. Usually described as an entrepreneur in Montana who followed the westward movement of speculators during the Gold Rush, Samuel paid for Edmonia's enrollment in a Baptist abolitionist boarding School in Albany. She left after about three years, she would say, because she resisted conformity. In 1859, at the age of 15, she was accepted into a preparatory program for eventual entrance into the progressive Oberlin College in Ohio, a school known for its acceptance of minority and female students. Along with approximately a dozen white female students, Lewis boarded with Reverend John Keep, a fervent abolitionist and spokesperson for the benefits of coeducation among races. He was a member of Oberlin's Board of Trustees.

During her first year in Oberlin's college preparatory department, she adopted the first name of Mary, and attended a variety of classes including zoology, French, and rhetoric. She was allowed to attend, free of charge, a "linear drawing" class. She also attended sculpture and other art classes, and was reportedly described as having a "lively sense of humor and a fondness for harmless mischief." She also seemed to live and work peaceably with her white housemates, and followed college rules.

Her successful three years at Oberlin came to a crashing halt when an incident involving two other classmates and its unfortunate aftermath resulted in her ultimate departure. On January 27, 1862, during a college recess, two white housemates of Lewis announced plans to go on an unchaperoned sleigh ride with their boyfriends. Lewis prepared and served spiced wine to the young women so that they would be braced for the cold evening. On their outing, the housemates became seriously ill. Their symptoms reportedly pointed to poisoning. Later documented medical testimony identified one ingredient that Lewis had added to the spiced wine: cantharides, the so-called aphrodisiac more popularly known as Spanish Fly. Charges were filed against her and a trial was to follow. However, she was not taken into custody. The Oberlin town press did not address the incident for several weeks. It is perhaps this lack of official outrage over the incident that prompted unofficial action on the part of some citizens.

On one dark and cold evening, as she stepped out of the home of Reverend Keep where she still lived, Lewis was seized, dragged to an open field and badly beaten. Local news stories began to emerge, although they did not address what had happened to Lewis, and they also refrained from naming her.

Her court hearings were delayed because of the seriousness of her injuries. Finally, on February 27, 1862 attorney John Mercer Langston, a man of racially mixed heritage himself, and an Oberlin graduate, defended her in a highly publicized hearing to determine if Lewis could even be indicted. Langston obtained a verdict of "insufficient evidence." Unfortunately, Lewis sustained additional mischaracterizations on two other, later occasions. She was accused of stealing art supplies in 1863, but charges were dropped due to insufficient evidence. Later that same year, she was accused of aiding and abetting a local burglar. She ultimately left Oberlin altogether, and without a degree in hand.

Continuing to be supported by her brother, Lewis went to Boston in hopes of pursuing a career in art in early 1864. A letter of recommendation from Reverend aided her in joining a receptive abolitionist community. The sight of a statue of Benjamin Franklin inspired her to pursue working in sculpture. She was eventually apprenticed under sculptor Edward Augustus Brackett (1818-1908), who created the bust (1860) of prominent abolitionist John Brown (1800-59). In later interviews, Lewis remarked that "a man who made the bust of John Brown must be a friend of my people." In addition to artistic training and guidance, Brackett gave her some clay and tools and some small, chipped pieces of statuary from which to model copies.

Lewis quickly mastered the basic techniques of modelling and casting. Brackett was pleased with her work. She created plaster medallions and busts of famous abolitionists. Her first professional work of art was a plaster medallion of John Brown. Abolitionist press elevated her as a prime example for their cause. Prominent abolitionist Lydia Maria Child (1802-80) interviewed Lewis several times and published articles about her work in important abolitionist newspapers. Expressing awareness of her marginalized racial status and how it could affect critical reception of her and her work, Lewis was reported to have told Child: "Some praise me because I am a colored girl, and I don't want that kind of praise. I had rather you would point out my defects, for that will teach me something."

In 1864, Lewis participated in a fair to raise money for Massachusetts' three black regiments organized by the Boston Colored Ladies' Sanitary Commission. She presented portrayals of two heroes of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry: a full-length figure of Sargeant William H. Carney (now lost), the first black man to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, and a bust of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, inscribed with the words, "Martyr for Freedom." Shaw commanded the Infantry, and was killed at the second battle of Fort Wagner in 1863. Lewis had seen that 54th Massachusetts Regiment - the first black Union regiment from the North - marching through Boston in May 1863, and had admired Shaw's dedication to the abolitionist cause. Her portrait bust was a success and established her early reputation. Shaw's family purchased one bust in recognition of her homage. By selling photographs as well as copies of the Shaw bust, Lewis financed a trip to Italy in 1865. She was quoted as having said, "I was practically driven to Rome in order to obtain the opportunities for art culture, and to find a social atmosphere where I was not constantly reminded of my color. The land of liberty [America] had no room for a colored sculptor." Lewis and other American female sculptors felt that they could live and work more freely without the gendered constraints that were so common at the time. Rome offered an unparalleled sculptural legacy in its collections of ancient, Renaissance and Baroque works, proximity to fine marble quarries, and an existing community of expatriate artists who cared far less about single women wielding mallets and chisels.

Mature Period

Lewis spent most of her career in Italy. She first arrived in Florence in 1865, and met artists Hiram Powers (1805-73) and Thomas Ball (1819-1911). Under their guidance, she improved her sculpture techniques She then departed for Rome in 1866, and remained for several years. She renewed her friendship with sculptor Harriet Hosmer (1830-1908) and joined a community of expatriate female American and British sculptors.

She lived and worked in a studio that was once occupied by famous Italian sculptor Antonio Canova (1757-1822) and began sculpting in marble. Like most sculptors in the 19th century, she worked in the Neoclassical style, evoking the white marble works of ancient Greek and Roman sculptors. While making commissioned small busts, she also crafted full-length sculptures. To jointly prove that her works were entirely original to her and to save money, Lewis executed her maquettes and enlarged final pieces entirely without the help of assistants. In 1867, only a year after her arrival in Rome, she completed Forever Free, a depiction of two freed African slaves. In October 1869, she returned to the United States to attend the sculpture's dedication at Tremont Temple in Boston. The statue was formally presented to prominent abolitionist minister Reverend Leonard A. Grimes.

Lewis' presence in Rome was quickly acknowledged in the Italian and European press. Articles about both her life story and about her work appeared favorably in the press. Henry James (1843-1916) famously described her as "a negress, whose color, picturesquely contrasting with that of her plastic material was the pleading agent of her fame." Using language of the era and regardless of the irony, his inclusion of Lewis among members of what he called "the "White Marmorean Flock" emphasized her success. She was very productive and her work was much in demand. Her studio, listed with those of other artists in the best guidebooks for Rome, was a fashionable stop for Americans on their Grand Tour of Italy and the rest of Europe. Strong-willed and independent, she wielded her chisel and mallet in front of visiting tourists and Italian art world figures in her studio, aware of the performative power of her exotic appearance, gender and skills.

Most of her works are based on literary, historical and racial themes. Capitalizing on her Native American heritage, she followed the sculptural fashion of the day by basing some works on the enormously famous Song of Hiawatha poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-82). These sculptures were an immediate success for Lewis.

Longfellow would later sit for a bust in her studio in Rome. Other portrait busts by Lewis include those of Abraham Lincoln, famous abolitionists, and personalities, as well as characters from the Bible and the Greco-Roman mythology. To refine her skills, she copied classical sculptures from public collections in Rome. A devout Catholic, she created a number of religious works. Collectors purchased these works to adorn their fireplace mantels and front parlors. These commissions provided her with a rather steady income.

During her time in Italy, she received professional support from both Charlotte Cushman (1816-76), a Boston actress and a pivotal figure for expatriate sculptors in Rome, and Maria Weston Chapman (1806-85), a dedicated activist for the anti-slavery cause. Cushman introduced Lewis to the larger immigrant community and visiting tourists at her frequent evening soirees, directed people to Lewis's studio, and even assisted the artist financially by facilitating collectors' acquisitions of her work.

Lewis would return to the United States for only a few visits. On a trip to Chicago in the 1870s, she sat for a series of carte de visite pictures, posing both in her sculptor's cap and jacket, and in a voluminous dark shawl. These pictures are the only known portraits of the artist.

Late Period

Her documented years in Italy culminated in the 1876 completion of what many consider to be her masterpiece, the Death of Cleopatra. This 3000-pound sculpture was prepared especially for the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, a very large and important fair that both celebrated the centennial anniversary of America's Declaration of Independence as well as promoted the most recent developments in technology, craft and art of the post-Civil War era. Lewis was one of only two Black artists to participate. Along with all of the American expatriate sculptors living and working in Rome (the remainder of which were Caucasian) Lewis was invited to participate in this very important event. She and several other sculptors elected to portray Cleopatra in stone. This fervent interest in the Egyptian queen reflected the height of an era of American cultural fascination with ancient Egypt, which was acknowledged as the birthplace of Western Civilization. For abolitionists and Black intellectuals, it was also becoming more closely associated with an increasing sensibility of cosmopolitan Blackness, a highly civilized Africa. Lewis' depiction of Cleopatra represents the Egyptian queen sitting on her throne just after her (self-inflicted) death by snakebite. The queen's facial features and hair do not illustrate her African heritage, however. She instead possesses the typical features and appearance of any white, Neoclassical female figure. Lewis may have wished her Cleopatra to be seen more as a white slave owner. She may have also wanted to enforce some distance between herself as a Black woman and the subject of her sculpture. Critics responded enthusiastically to the work, generally praising its emotional qualities but also sometimes over-focusing on the artist's minority status.

The sculpture's history beyond the Exposition is unique. Because it did not sell at the exhibition, it was placed in storage. In 1878, it was brought to the Chicago Interstate Exposition. It was possibly sold there and then placed in a saloon in Chicago. Gambler and owner of the Harlem Racetrack "Blind John" Condon purchased it from the bar owner to mark the grave of a racehorse he had owned named "Cleopatra." The grave was in front of the grandstand of the race track in the Chicago suburb known as Forest Park. In the 1970s, the statue was moved to a storage yard where it remained for years. When a member of the Forest Park Historical Society acquired the statue in 1985 and placed it in storage at the Forest Park Mall, further research on the work was finally was conducted. Much restoration and conservation was conducted on the damaged sculpture, and it was donated to the Smithsonian Museum of American Art.

Upon Lewis' return to Rome, she received even more sculpture commissions. Between 1872 and 1879, she created more busts of abolitionists. In 1877, former US President Ulysses Grant sat for her as a portrait subject during his visit to Rome.

Mystery shrouds the remainder of Lewis' life. With a decline in Neoclassicism's popularity came a decline in demand for her work by the 1880s. By 1901, she had moved to London. She apparently lived in the Hammersmith area, and died there in 1907. Her death certificate indicates Bright's disease, a kidney condition, as the cause of her demise.

Lewis was buried in an unmarked grave at St. Mary's Roman Catholic Cemetery. In 2017, a successful fundraiser paid for the placement of an identifying marker on Lewis' burial spot.

The Legacy of Edmonia Lewis

Edmonia Lewis' life and achievements have inspired other artists, notably the female artists of the Harlem Renaissance movement. Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller must have had Lewis' works in mind when she created her famous Ethiopia Awakening in 1921. Like Fuller, contemporary American artist Kara Walker was probably aware of Lewis' achievements. In her well-known black-and-white silhouettes, Walker explores race and gender issues, often related to the history of slavery. Her exploitation of this popular Victorian portrait format, relates even more to Lewis' work backgrounded by the same era.

Renewed interest in - and scholarship on - the artist has occurred in recent years. Lewis' contributions to art and to black history are the object of ongoing research today. Although she received a lot of attention in her lifetime, she was not fully artistically recognized until after her death. The rescue and restoration of Lewis' Dying Cleopatra sculpture helped fuel this resurgence of interest in her life and career. A number of her most famous works are included in major museums across the United States and have been featured in several important exhibitions. Others are lost to us.

In order to overcome an early life and career interests compromised by both race and gender issues of the late 19th century, Lewis had to effect literal distance from the country of her birth. When called upon to talk about herself, she embellished parts of her own biography in order to enhance her exotic past and lend a heightened narrative to her Neoclassical sculpture. Lewis' chosen subjects both appealed to popular American art tastes and collectors of an abolitionist mindset. And yet, the figures populating those subjects only selectively resembled the actual appearance of indigenous American or African individuals. This points to the continued artistic negotiations Lewis may have struck with fusing her persona and the issues of the day with her work. This preferred avoidance of viewers' potentially conflating the artist and the art they create can be inferred from statements made by 20th century female artists such as Georgia O'Keeffe, who resolutely asserted that she wished to be known as an artist instead of a woman artist, even while her greatest champion Alfred Stieglitz promoted her work as a kind of embodiment of liberated, often eroticized womanhood.

Influences and Connections

-

![Harriet Hosmer]() Harriet Hosmer

Harriet Hosmer - William Bracket

- Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller

-

![Harlem Renaissance]() Harlem Renaissance

Harlem Renaissance ![Modern Sculpture]() Modern Sculpture

Modern Sculpture

Useful Resources on Edmonia Lewis

- The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis. A Narrative BiographyOur PickBy Harry Henderson and Albert Henderson

- Child of the Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History's Black and Indian SubjectOur PickBy Kirsten Pai Buick

- Stone Mirrors: The Sculpture and Silence of Edmonia LewisBy Jeannine Atkins

- Edmonia Lewis: Internationally Renowned Sculptor (Celebrating Black Artists)By Charlotte Etinde-Crompton and Samuel Willard Crompton

- Edmonia Lewis: Wildfire in MarbleBy Rinna Evelyn Wolfe