Summary of Black Mountain College

The experimental school Black Mountain College became a crucible for mid-20th century avant-garde art, music, and poetry. Founded on the principles of balancing the humanities, arts, and manual labor within a democratic, communal structure, the school's mission was to create "complete" people. It attracted a range of prominent teachers, including Bauhaus artists Josef and Anni Albers, composer John Cage, painter Willem de Kooning, and poet Charles Olson. With an emphasis on interdisciplinary work and experimentation, students such as Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, Ray Johnson, Kenneth Noland, and Ruth Asawa went on to make significant contributions to avant-garde art. After almost 25 years, the school closed for lack of money and students, but its importance and legacy has continued to grow to this day.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Even if not perfectly realized, Black Mountain College's experiment in community-centered education remains one of its most important legacies. The experience of education in a communal setting, where traditional hierarchies between faculty and students were subverted, was meant to imbue the individual student with a sense of his or her relations to others and the environment.

- The school had (practically) no grades and no tests, and students designed their own course schedules and concentrations. While there were classes in mathematics, psychology, and literature, the visual arts and music were at the heart of the school's curriculum in order to foster the decision making that the founders understood to be foundational to a democratic society.

- Josef Albers' previous teaching at the Bauhaus greatly informed the arts curriculum at Black Mountain College. Promoting both fine arts and craft, there was an emphasis on the hand made process. Additionally, Albers was insistent on providing training in the fundamental areas of drawing and color, and he promoted discovery and experimentation. Albers' assignments encouraged controlled trials with color and materials, but with the arrival of John Cage, experimentation using spontaneity and chance methods became more popular. These two approaches to learning had long-lasting influences in post-war art.

Artworks and Artists of Black Mountain College

Monte Albán

Anni Albers studied with both Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee when she was a student at the Bauhaus in Germany. Their commitment to abstraction as well as their interests in the arts of non-Western cultures, in addition to Albers' own wide-ranging readings and knowledge of Pre-Columbian textiles, informed Albers' methods and abstract motifs for weaving.

The weaving Monte Albán is indicative of the scale, abstraction, and colors that Albers used while at the Bauhaus, but it is also informed by her interest in Mexican and South American cultures. After coming to Black Mountain College in 1933, Albers, along with her husband Josef and friends Theodore and Barbara Dreier, travelled to Mexico for the first time. Here, she was inspired by the sculpture, pottery, and architecture of ancient civilizations and the prevalence of Mexican folk art. While she had previously been opposed to pictorial motifs, the lines in this particular weaving, created by additional weft threads, are based on the lines of Zapotec architecture.

Albers founded the weaving program at Black Mountain College, incorporating many Bauhaus ideas. Ultimately, weaving for Albers was an opportunity for experimentation unburdened by traditional rules. She wrote, "Material, that is to say unformed or unshaped matter, is the field where authority blocks independent experimentation less than in many other fields, and for this reason it seems well fitted to become the training round for invention and free speculation." As with so many other subjects at Black Mountain, hands-on learning and exploration attuned the students to the freedom of creative processes.

Silk, linen, and wool - Harvard Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Leaf Study IX

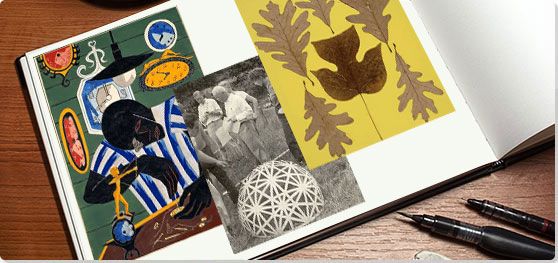

Josef Albers made it his mission to teach students how to see, to probe relationships between forms and color, and to notice what one usually passes over. In addition to his famed classes on color theory, matière studies were a staple of Albers' pedagogy. Here, he had students use found objects to create compositions in order to create relationships between textures, colors, and lines.

In his own matière study, Albers arranged six leaves symmetrically on a yellow sheet of paper. The symmetry of the composition echoes the symmetry of the leaves, while the organic and varied lines of the leaves undermine the strict orderliness of the composition, creating a playful tension. Frederick Horowitz notes that the poverty experienced at Black Mountain led Albers to have to improvise with materials at hand, but as he points out, "Their having to rely on cheap and discarded materials encouraged Albers's students to experiment and take risks, took the preciousness out of art, and underscored the idea that this was study, not art."

Additionally, Albers impressed upon his students that the formal relationships they created and found in their compositions had a parallel in human behavior and relationships as well. Horowitz explains, "...Albers conceived of talking about the formal elements as though they were living creatures. Lines, shapes, colors, and materials, 'should know about each other,' ... 'they should support each other, not kill each other.'"

Evidently, Albers had a particular soft spot for autumn leaves, telling his students, "You mustn't think of the autumn as a time of sadness, when winter is coming, because all the trees, they know winter is coming, so they get drunk! With color! Ach, it's beautiful! So now bring in leaf studies."

Leaves and adhesive on colored paper - The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

Watchmaker

The figure in Jacob Lawrence's Watchmaker fills almost the entire canvas. Painted in a matte black and outlined in white, blue, and red, the craftsman, wearing a monocle, works intently at repairing a watch. A single light fixture hangs above to illuminate his task, and several clocks hang on the green paneled wall behind him, each displaying a different time. The disparity of the times and the angle of the table create a sense of dizziness and confusion, recalling Cubist space, and yet the intensity of the watchmaker's attention creates a stillness and quietness.

Lawrence was invited by Josef Albers to teach during the 1946 summer session. Though the two artists had very different methods of working and subject matters, Lawrence admitted that outside of his teachers in Harlem, Albers exerted the greatest influence. During this time, perhaps spurred by Albers, Lawrence used bold colors to create his compositions.

It is perhaps fitting that Lawrence chose this subject for a painting while at Black Mountain. While he recalled that the subject came from a watch repair shop he passed daily in Harlem in the 1930s, the focus on the tools and craftsmanship meld with Black Mountain's overall mission. As Bryan Barcena writes, "The tools of the craftsman's trade...are representative of a bridging of the haptic divide between tactile and visual concentration; their presence underscores the hand-eye choreography performed by the craftsman." The emphasis on craftsmanship - as opposed to fine arts - and materials at Black Mountain was central to the school's curriculum.

It was also at this moment in the school's history when the faculty and students made a concerted effort to try to integrate the campus, a controversial endeavor as the school was situated in the deep South during the era of Jim Crow. While their efforts were not altogether successful in the long run, they were more than a decade ahead of the desegregation efforts enforced in the South during the 1960s.

Tempera and graphite on paper - Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution

Asheville

While teaching during the 1948 summer session, de Kooning created Asheville over the course of a couple of months. At first, the all-over composition appears abstract, but upon close inspection, one finds eyes, hands, and a mouth, among other shapes. Additionally, the outline at the top center may suggest the Blue Ridge mountains, and the blue below that may make reference to Lake Eden, the site of Black Mountain College. The painting contains multiple layers though it is not thickly painted, as de Kooning would often scrape down a day's work and start fresh again on the cardboard the next day.

Josef Albers had a tendency of inviting faculty that he knew were completely different from himself, and de Kooning was no exception. His painting style caused much confusion among many of the faculty and students. While de Kooning and Albers had very different creative processes, de Kooning's use of collage technique was something that the artists shared. Asheville is not a collage in the traditional sense of combining various materials, but the composition recalls a collage with fragmented shapes placed next to each other, each outlined in black. Additionally, in the upper left, a grey circle with a line through it resembles a tack, which de Kooning would often use to temporarily adhere paper in different shapes to the canvas as he was working out the composition, thus further underscoring the painting's connection with collage. As Thomas Hess described the painting, it was "of sliced and torn paintings and drawings, pinned and tacked and taped together...."

Oil and enamel on cardboard - The Phillips Collection, Washington DC

Buckminster Fuller class, with Elaine de Kooning and Josef Albers, constructing the geodesic dome

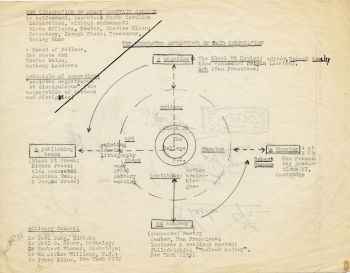

In addition to Willem de Kooning, John Cage, and Merce Cunningham, the summer of 1948 also saw the arrival of the inventor/architect/engineer Buckminster Fuller. Fuller's goal that summer was to construct the first geodesic dome that he had designed. Like the Bauhaus architects, Fuller was committed to the betterment of society through architecture and technology, but he used radically different forms from the Bauhaus school. His designs were based on the tetrahedron and sphere instead of the cube. As Mary Emma Harris describes it, "The dome...was to be 22 feet high, have a floor area of 1500 square feet, and weigh fewer than 270 pounds." Fuller hoped to revolutionize modern dwellings and make them more affordable.

With the help of students, Josef Albers, and Elaine de Kooning, Fuller attempted to erect his geodesic dome from venetian blind strips. Once joined together, the tensile strength of the bolted-together strips would cause the structure to pop up into a hemisphere. Unfortunately, the material was not strong enough, and the hemisphere failed to materialize. Fuller jokingly called it the "Supine Dome," and he remained undaunted by the failure. Ultimately, Fuller wanted to, in the words of curator Bryan Barcena, "[carve] a path to the future founded in the belief in collaboration, universality, interrelatedness, and a technocratic allegiance to progress through design."

Photograph

Quiet House Door

Hazel Larsen Archer came to Black Mountain College as a student for the 1944 Summer Session and then enrolled full time, and in 1949 she was admitted as part of the faculty, teaching photography. Her portraits of students and faculty, such as Willem de Kooning and Buckminster Fuller, are integral to any documentation of campus life at Black Mountain.

In Quiet House Doors, Archer captures the play of light and shadow on two simple doors. The doors opened to a small, chapel like structure built to commemorate the son of Theodore Dreier who died in a tragic car accident in 1941. As art historian Alice Sebrell explains, "Quiet House represented a place of solace, retreat, and renewal for this predominantly secular community." By exploring the simplest of forms, Archer aimed to convey the essence of things without unnecessary distractions. She credited Josef Albers and Buckminster Fuller for teaching her how to see.

Archer's own pedagogical methods centered around the student, encouraging his or her own self-discovery. She thought of the teacher more as "an usher" than an imparter of knowledge. She helped her students to look closely and taught them the craft of fine printing.

Gelatin silver print - Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer and Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center

Untitled (Night Blooming)

In this largely monochromatic black painting, Rauschenberg created a thick, textured surface, in part by pressing the freshly painted canvas into the dirt and gravel road at Black Mountain College. The canvas carries not only the impressions of countless small rocks, but some of those rocks actually adhered to the canvas resulting in a highly tactile surface. The thin white line that occupies the center of the canvas reaches from the horizontal ground up to the top where it barely pokes through the black textured surface to continue faintly along the horizon line. At the top center, a barely perceptible orb hangs above the white line, suggestive of a moon. As art historian Branden Joseph points out, the night blooming flowers of North Carolina include jasmine, honeysuckle, and sweet gardenia, thus the painting taps into not only our sense of sight and touch but also smell.

Rauschenberg spent two stints at Black Mountain. The first was in 1948 with his then-wife Susan Weil, where they experimented with light-sensitive paper, making photograms, and the second in 1951 when he began exploring photography, painted his infamous White Paintings, and a series of black paintings, including the Night Blooming series. During this time, he and Weil separated and he developed a relationship with Cy Twombly. Rauschenberg whole-heartedly embraced Black Mountain's ethos of experimentation and collaboration, which he sustained throughout his long career.

Oil, asphaltum, and gravel on canvas - The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas

Vase

Voulkos was invited to teach ceramics at the 1953 Summer Session. While the Black Mountain ceramics program did not get started until 1949-50, mostly because Josef Albers did not think working in clay provided enough rigor, it attracted much attention. Initially conceived as a place for functional, production pottery, many of the potters came to embrace the college's focus on experimentation. Voulkos, himself, created functional pottery in his early years, of which this stoneware vase is exemplary.

He was deeply influenced by the Japanese Mingei school, which as curator Cindi Strauss explains, "brought with them a philosophy of elevating craftsmanship with serial production." The bulbous shape of the vase, its earth-colored glaze, and the irregular horizontal lines combine to create an organic feel. Because of his time at Black Mountain, where he first experienced a creative community of artists, and a trip to New York, where he met Abstract Expressionists Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, Voulkos would come to develop a more radical, expressionist style. By 1956, he largely abandoned functional pottery for ceramic sculpture that embodied the spontaneity of Abstract Expressionism and the chance techniques of John Cage.

Stoneware - Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts

Early Years

After being dismissed from Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida for protesting curricular changes and violations of academic freedoms, John Andrew Rice, Theodore Dreier, and other former faculty members founded Black Mountain College near Asheville, North Carolina in 1933. Rice, a classicist and educational maverick inspired by the educational theories of John Dewey, and Dreier, a physicist and nephew of collector, artist, and educator Katherine Dreier, shaped the school's faculty and institutional life in the earliest years. Together, they sought to form a liberal arts college based on Dewey's principles of progressive education that emphasized personal experience over delivered knowledge.

The original 22 students mostly followed Rice and Dreier from Rollins College, and many of the students came from poor families who could not afford college tuition. According to historian Martin Duberman, by the mid-1930s, most of the students enrolled, around 50 or so, came from the Northeast, and had heard of the school by word-of-mouth. Students took classes in philosophy, languages, economics, psychology, mathematics, and the arts, among others. With no pre-determined concentrations, students devised their own curricula in consultation with faculty advisors. While there were no grades given (although students grades were recorded for transfer purposes), promotion from the junior to senior division, as well as one's graduation, depended, in part, on one's performance on oral and written exams, often assessed by an expert in that field from outside the college. The school was never accredited, which perhaps kept enrollment low through the 1940s and 1950s.

The school placed equal weight on academia, the arts, and manual labor and fostered an egalitarian, democratic environment. Here, students, faculty, and trustees all had a voice in the running of the school, and students and faculty alike lived on campus, ate in the same dining halls, and participated in community life. In addition to a balanced curriculum of academics and arts, Rice insisted that the students and faculty work at the college to aid in the creation of "complete" people and make the school self-sufficient. They maintained a farm and built the buildings on campus. In these early years, an egalitarian and communal environment thrived.

While the school emphasized a well-rounded curriculum of humanities and science courses, the arts were a foundational component of the curriculum. Rice saw the arts as crucial for preparing the individual for participation in a democracy. As the first catalogue explained, "Through some kind of art experience, which is not necessarily the same as self-expression, the student can come to the realization of order in the world and, by being sensitized to the movement, form, sound, and the other media of the arts, gets a firmer control of himself and his environment than is possible through purely intellectual effort." To shape the arts curriculum, Rice recruited Josef Albers, who had just been expelled from the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany when the Nazis closed the school. Albers incorporated the Bauhaus' interdisciplinary approach to the arts, combining fine and decorative arts with craft, architecture, theater, and music.

Albers focused his teaching on drawing, color, and working with various materials, all fundamental for budding artists. As Helen Molesworth explains, "Looking, handwork, and critical assessment were the backbone of the Albers pedagogic method." He did not encourage self-expression, but his methods were open-ended and had profound impacts on many of his students.

The 1940s and World War II

In the late 1930s, the school bought property a few miles from the original campus, and began building new structures. By this time, Rice was having conflicts with other faculty members, felt uneasy about the move and the labor that would be required to create the new campus, and ultimately, he felt that the college was not living up to the ideal standards he envisioned. He resigned his rectorship in 1940.

With Rice no longer in the picture, Josef Albers' influence grew, and the arts flourished at the Black Mountain. Starting in 1944, the school began hosting summer institutes that offered a multitude of educational opportunities and enticed talented musicians, dancers, painters, photographers, visual artists, thinkers and educators to join the summer faculty as its reputation grew. Over the years, the summer faculty included Robert Motherwell, Walter Gropius, Jacob Lawrence, Willem de Kooning, John Cage, Alfred Kazin, Merce Cunningham, Clement Greenberg, and Paul Goodman, among others. These were some of the most intensely creative periods for the college. While these high-profile thinkers and artists brought much attention and acclaim to the school, historian Martin Duberman suggests that they were peripheral to the school's mission and ethos and did not foster the community spirit that thrived during the rest of the year. Despite this assessment, the summer of 1948 was perhaps one of the most famous summers in Black Mountain's history. Willem and Elaine de Kooning were present as were John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and the architect Buckminster Fuller. In addition to the performance of Erik Satie's play, The Ruse of Medusa, the sets for which were designed by Willem de Kooning, the school saw the first attempt at erecting one of Fuller's Geodesic domes.

Critical to the school's success after the World War II was the GI Bill, which paid college tuition for returning soldiers. While there was in-fighting among many of the year-round faculty, students eagerly flocked to the school to experience the creative community.

Late Period and Closure

By 1948, the in-fighting among the faculty reached a nadir, and it became clear that they needed to reconsider the curriculum. It was difficult for the school to maintain faculty across a variety of disciplines, and it was decided that the curriculum should be reduced to music and visual arts; however this new plan was not feasible. In the face of a messy reorganization, Theodore Dreier and Josef and Anni Albers resigned from Black Mountain College in 1949. Their departure, though, did not expedite or make clearer the reorganization, as the remaining faculty could not agree on the future of the College, creating a fissure within the community. By the end of the 1953 Summer Session, most of the students and faculty had moved on to New York City or San Francisco. With few students and only a handful of faculty, including Charles Olson and Dan Rice, it was clear that the school would not exist much longer.

Despite the ongoing problems of faculty governance and curriculum disputes, the school saw many important avant-garde experiments in the first half of the 1950s. In 1951, poet Charles Olson returned to Black Mountain College to teach and became the dominant figure at the College until its closure. Under his guidance, Robert Creeley founded Black Mountain Review in 1954. Despite its short lifespan (ceasing publication in the fall of 1957) the radical literary magazine played an important role in the twentieth-century American literary scene, featuring experimental pieces by the future-Beat poet Alan Ginsberg and Olson's own Projected Verse.

In 1952, John Cage along with the musician David Tudor staged the first "Happenings" at Black Mountain College. Cage conscripted Robert Rauschenberg, Charles Olson, M.C. Richards, and Merce Cunningham to perform various actions of their choosing at set times. The result was a cacophonous performance with no one center of attention. Poems were read, a lecture given, records played, dancers performed through the dining hall, and Rauschenberg's White Paintings were displayed, but no one who saw the event describes it in the same way.

Taking on the rectorship in 1954, Olson attempted to resuscitate Black Mountain College, but mounting debts forced the school to sell off buildings and land. The internal disputes among the administrators also continued, and the school fully closed its doors in 1957.

Later Developments - After Black Mountain College

While Black Mountain College existed for only twenty-three years, it left an indelible mark on the American art scene in both San Francisco and New York. Some of the most influential American artists of the twentieth century can be counted among its students and faculty, and the school's communal ethos was essential to the development of American arts and counterculture in the second half of the twentieth century. As art historian Mary Emma Harris points out, Black Mountain also anticipated many of the challenges that faced universities in the 1960s, "such as the involvement of students and faculty in the administrative and decision-making process, the pass/fail system, and a more flexible curriculum." While there are no schools now in existence like Black Mountain College, Warren Wilson College in North Carolina provides a strong liberal arts education with on-campus work and community engagement. Black Mountain also served as a model for later intentional communities that promoted a cooperative way of living and art-making.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI