Summary of Katherine Dreier

The American artist and collector Katherine Dreier championed modern, avant-garde art in the United States starting in the 1920s when such art was regularly decried as abject, inscrutable, a hoax. While academically trained as a painter, Dreier was one of the first Americans to embrace the modern art that was being made in Europe by the likes of the Post-Impressionists, German Expressionists, and Constructivists. Deeply influenced by the spiritual and theosophical writings of Wassily Kandinsky, Dreier proselytized the spiritual rejuvenation offered by these approaches to art. Along with the Dadaists Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, Dreier co-founded the Société Anonyme, a radical group of artists that sought to disseminate a diverse art to the masses through exhibitions and lectures. Through her own paintings as well as her collecting habits, Dreier was an important force in popularizing modernism in the United States.

Accomplishments

- As a painter, Dreier synthesized the lessons of van Gogh and Kandinsky to create a highly personalized art that aimed to reflect the inner spirit. Moving between representational and abstract styles, Dreier combined color and form in bold ways for expressive ends.

- A believer of Theosophy, a religion built on mystical and occult philosophies that flourished at the turn of the 20th century, Dreier had faith in the power of art to prod humanity's evolution to a higher spiritual awareness. Inspired by Wassily Kandinsky's own writings on the spirituality of art, Dreier incorporated the symbolic shapes and colors laid out by Kandinsky to convey the cosmic and transcendental meaning of her subjects.

- While Dreier painted throughout her life, her mission to collect modern art and educate the larger American public on its significance took up most of her energies. Through the Société Anonyme, Dreier curated numerous exhibitions and delivered countless lectures to introduce and demystify the new, avant-garde painting and sculpture. She was adamant that it was through living with the art and experiencing it that one could come to understand and appreciate it.

Important Art by Katherine Dreier

Landscape with Figures in Woods

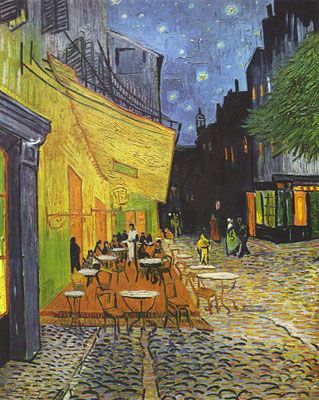

Dreier's Landscape with Figures in Woods - previously known as The Avenue, Holland - was one of two paintings exhibited by the artist at the New York Armory Show in 1913. A raised path, lined with trees, curves through the center of the composition, and several solitary individuals walk along it. Painted in lush greens and blues and warm earth colors, the scene embodies the quiet grandeur of the landscape. The subject-matter of the painting - a view which must have captured her attention during her trip in Holland earlier that year - is, as it is often pointed out, quite conventional, reflecting her early academic training.

Borrowing from Impressionist and Post-Impressionist styles, Dreier aims less at an objective representation of the scene than an expressive rendering of it. Thus, while Landscape with Figures in Woods does not in any way prepare the viewer for the leap into abstraction that Dreier would soon take, it can be said that she, following van Gogh whose work she very much admired, was already a proponent of a highly personal art.

While Landscape with Figures in Woods was not remarked upon when it was in the Armory Show, when it was shown a second time at Macbeth Gallery, it garnered a number of positive reviews, including one from the New York Times. "Although sufficiently conventional in subject, [it] is put together with definite attention to the division of the space into ample and agreeable minor spaces. ...notable chiefly for this tact in the disposition of the lines and masses, [it has an] ability to speak the decorator's proper language with force enough to be heard at a distance."

Oil on canvas - George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum, Springfield, Massachusetts

Abstract Portrait of Marcel Duchamp

Painted in 1918, Portrait of Marcel Duchamp attests to the thorough transformation that Dreier's art underwent in the years following the Armory Show. Eschewing the traditional representational nature of her earlier work, Dreier renders her dear friend in an abstract, non-figurative manner. Rich yellows, blues, reds, and violets combine with triangles, circles, and other shapes to create a cacophonous composition. One searches the painting for some clues to Duchamp's identity, and perhaps one sees the letter D in the center and a pipe at center-left. Dreier, though, was not necessarily interested in these likenesses, instead she wanted to portray Duchamp's inner life. Of this painting, Dreier wrote, "[T]hrough the balances of curves, angles, and squares, through broken or straight lines, or harmoniously flowing ones, through color harmony or discord, through vibrant or subdued tones, cold or warm, there arises a representation of the character which suggests clearly the person in question, and brings more pleasure to those you understand, than would an ordinary portrait representing only the figure and face."

The work celebrates Duchamp, who, in Dreier's eyes, combined "originality of so high a grade" with "such a strength of character and spiritual sensitiveness," but its style owes much to another of Dreier's favored artists - the Russian abstractionist Wassily Kandinsky. While studying in Germany in 1912, Dreier read Kandinsky's On the Spiritual in Art and was inspired both by his view of "form as the outward expression of inner spiritual meaning" and by his synthesis of form and color. The two also shared an interest in the non-traditional, occult religion of Theosophy and the writings of Rudolph Steiner. The art historian Francis Naumann points out that in Kandinsky's treatise, the triangle suggests mystical enlightenment. The prominence of triangles in the composition suggest that Dreier saw him as an enlightened individual. She said of him, "I have always considered [Duchamp] one of the most advanced spirits of our Time," and Dreier once said, "and though I did not always understand what he was doing I was intuitive enough to let Time reveal it to me."

In the same year as completing the abstract portrait, Dreier commissioned Duchamp to produce a painting to hang above the bookshelves of her Manhattan apartment. The resulting work, Tu m', was to be Duchamp's last painting on canvas.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

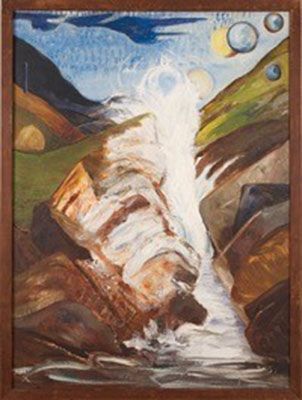

Waterfall

If Dreier's Abstract Portrait of Marcel Duchamp simultaneously exhibits her facility with abstraction, her Waterfall of 1931 serves as a reminder "of the range of her style and the character of her contribution to the modern movement," as the 1952 Yale catalogue of the Société Anonyme's collection describes. Incorporating her love for rural landscapes as well as abstract elements, the work resists straight-forward, stylistic categorization.

Whether the painting represents a real waterfall or an imagined one is also not clear, as there is very little art-historical research surrounding the work. The idea to paint a waterfall could have been the result of seeing other works with the same subject, such as Kandinsky's Waterfall of 1909 or Shining Waters of 1920 by Louis M. Eilshemius, whose work Duchamp very much admired. Dreier's image, however, is not the product of a simple act of imitation but constitutes, rather, an individual expression borrowing elements from a variety of sources. The painted spheres at the top-right corner of the image can be read in relation to Kandinsky's understanding of the circle as an elementary form which "combines the concentric and the excentric in a single form, and in balance" and which has cosmic significance. Unlike Kandinsky, though, Dreier combines these mystical forms with a natural landscape. Dreier's waterfall could, finally, also have something to do with a need to give expression to her beliefs on art - heavily influenced by her Theosophical upbringing - and to the metaphor of water that she often employed in speaking about the subject: "The stream of art flows on," she wrote in 1948, "and must be constantly renewed by fresh waters not to become stagnant."

Oil on canvas - Location Unknown

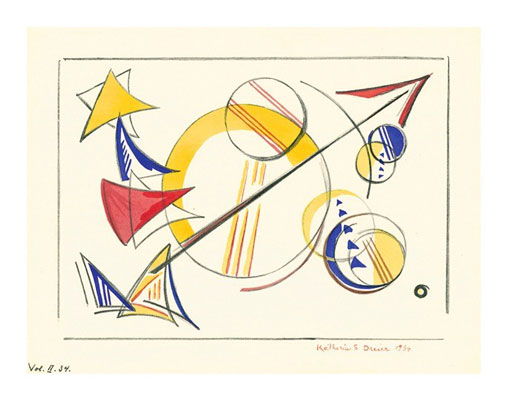

Variation 34, from 1 to 40 Variations

Whilst renting a studio on Place Dauphine in Paris during the 1930s, Katherine Dreier developed a series of lithographs, reproduced and published in 1937. Titled 40 Variations, this vibrant set of abstract images intended to capture musical experience in visual composition. "During 1933 two things were happening over here which greatly intrigued my imagination!," explained Dreier in her introduction to the series. "The first of these was the playing of Beethoven's Variations at many a concert during the winter months, and the other was the International Regatta during some of our most perfect summer days. Both events made a deep impression, and there flashed on my mind the query - why not translate these two experiences into the realm of abstract art?"

While Dreier acknowledged specific musical works as a source of inspiration for her Variations, music had played an important role in the way that Kandinsky understood and wrote about art. Using an elementary drawing as her foundation, Dreier introduced variation by a combination of hand-coloring and stenciling - a complicated printing process overseen by Duchamp - limiting herself to a palette of four colors: red, blue, yellow, and umber. The variation of colors attests to the significance of Kandinsky's work for Dreier. "Color," he wrote in Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911), "is a power which directly influences the soul. Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand which plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul." The purpose of great works of art, Kandinsky further argued, is to "'key [the soul] up,' so to speak, to a certain height, as a tuning-key the strings of a musical instrument."

Finally, while the different images in the series have the capacity to produce an effect of their own, as Moholy-Nagy revealed in his introduction to the edition, the value of examining these images side by side should not be underestimated. "The pages," he wrote, "miraculously transform themselves into a rapid movement, into a fluctuating pattern of fighting discords, strange harmony, an overwhelming surprise of sublime rhythms." Interestingly, this series by Dreier later served, as Claire Lui narrates, "as the basis for a dance piece, with choreography by Ted Shawn and music by Jess Meeker (and also for a line of silk fabrics, though no record of those fabrics remains)."

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York

Biography of Katherine Dreier

Childhood

Katherine Sophie Dreier was born into a fairly wealthy family in Brooklyn, New York. Her parents emigrated from Bremen, Germany in the 1850s during one of the largest flows of German immigration to the USA, and soon established a comfortable environment for themselves and five children. Theodor, Dreier's father, earned a substantial salary in an iron importing business. It is clear from several accounts that the Dreier home was a warm and progressive one and that Dreier and her siblings enjoyed the same opportunities independently of their gender and were also encouraged to understand and participate in social endeavors from an early age. Indeed, throughout their life, and following the example of their mother, Dorothea, all of Dreier's siblings and especially her three sisters, would exhibit an active commitment to social reform. Her sisters Mary and Margaret made significant contributions to the suffrage and labor movements, holding leadership positions in the Women's Trade Union League (WTUL) among other organizations. While Katherine was to follow in the steps of her older sister Dorothea, a Post-Impressionist painter, and become an artist, she herself engaged in social work throughout her life. Her approach to art and, later, collecting also reflected her commitment to democratic ideals.

Education and Early Training

Dreier already began taking private art lessons at the age of 12 and received formal training at the Brooklyn Art School between 1895 and 1897. In the following decade, funded by a large inheritance from her parents, Dreier took several trips to Europe, visiting prominent art collections - including that of Leo and Gertrude Stein in Paris - and continuing her artistic training. In 1900, Dreier joined her sister, Dorothea, to study painting at the Pratt Institute and, a year later, followed her back to Europe to examine the art of the Old Masters close-up.

Upon returning to New York, she continued her artistic training under Scottish-American painter Walter Shirlaw, who Dreier later admitted was instrumental in the formation of her understanding of art as free expression. For a few months in 1907, she studied with Raphaël Collin in Paris, and in 1912 she spent some time working under Gustaf Britsch, who she found to be the most skillful of her teachers. Having participated in a number of group exhibitions in Germany, Dreier had her first solo exhibition in London in 1911 at the Doré Galleries. During this time, she met artist Edward Trumbull through a mutual friend. The two married, but the marriage was quickly annulled when Dreier discovered that Trumbull already had a wife and children.

Despite this personal misfortune, Dreier remained productive. In 1912, she became treasurer of the German Home for Recreation of Women and Children and assisted in the foundation of the Little Italy Neighborhood Association in Brooklyn, and in 1913 she was invited to exhibit work at the groundbreaking Armory Show in New York City alongside modern artists such as Alexander Archipenko, Constantin Brancusi, Georges Braque, Robert Delaunay, Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Pablo Picasso. While the show garnered much exposure for Dreier's work, the critics' reviews were not enthusiastic. According to Naomi Blumberg, the response to her own work as well as to the work of the other radical artists "inspired Dreier to devote herself to promoting the work of modern artists, who were largely dismissed and misunderstood by American audiences."

Following her first solo show in the United States in 1913 at the Macbeth Gallery, Dreier, together with her sister Dorothea, founded the Cooperative Mural Workshop to further her commitment to making art public and accessible. Based on the examples of Old Master artists such as Titian and Veronese as well as the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain, the Workshop aimed, in the words of Dreier, "to band together a group of earnest painters who desired to express themselves in decorative art." In 1916, she joined the Society of Independent Artists, which exhibited the work of avant-garde artists. It was modeled on the French Société des Artistes Indépendants and was centered around art collector Walter Arensberg. During this time, Dreier met Marcel Duchamp, with whom she forged a lifelong friendship and collaborative partnership.

Mature Period

In 1920, Dreier, Duchamp and Man Ray founded the Société Anonyme, Inc., which sought to popularize modern art through exhibitions, lectures, and an extensive reference library as well as to support living artists no matter what their style. While the French name designates a company with anonymous partners, the inclusion of "Inc." on the end signals a commercial enterprise. The paradox of the "named unnamed" befit the Dada sensibilities of Duchamp and Man Ray. William Clark writes that Dreier "wanted to call it 'The Modern Ark,' perhaps symbolizing her shipping an unrivalled collection of European Modernism over the Atlantic...." As the Yale University catalogue accompanying the Memorial Exhibition of Dreier's private collection in 1952 makes clear, the Société Anonyme's objective was, above all, educational, "an international organization," the catalogue explains, "for the promotion of the study in America of the progressive in art, based on fundamental principles, and to render aid in conserving the vigor and vitality of the next expressions of beauty in the art of today."

It is worth noting that both of Dreier's collaborators, Duchamp and Man Ray, were most closely associated with Dada. While Dreier did not share the Dadaists' attacks on traditional art and bourgeois tastes, the fact that they could, despite their differences, come together for the purposes of the Société Anonyme is proof of the organization's open character. Indeed, it could be said that it was because of such differences that Société Anonyme became so successful. "Throughout the twenties," writes Clark, "Société Anonyme was New York's first museum of modern art - one without walls, we may add - presenting an international array of cubists, constructivists, expressionists, futurists, Bauhaus artists, and Dadaists. It hosted the first American one-person shows of Kandinsky, Klee, Campendonk, and Leger. Société Anonyme promoted some of the most progressive artistic experimentation to be done in the US country at the time."

In line with her educational mission, during the 1920s and until the end of her life, Dreier also wrote and lectured on modern art in diverse settings, including the Bauhaus and Black Mountain College, an experimental school founded by her nephew. Her books include Western Art and the New Era: An Introduction to Modern Art (1923) and the first book ever to be published in English on Vincent Van Gogh (1913).

The International Exhibition of Modern Art, 1926-27

In 1926 the Société Anonyme presented the International Exhibition of Modern Art at the Brooklyn Museum, a show of considerable size that included works by Jacques Villon, Francis Picabia, Fernand Leger, Piet Mondrian, Paul Klee, Joan Miró, Max Ernst, Kurt Schwitters and Georgia O'Keeffe, among others. The exhibition, with over 300 works by over 100 artists from 23 countries, was the largest exhibition of modern art since the infamous 1913 Armory Show.

Instead of adopting the traditional, vertical-installation style of the salon, Dreier decided to exhibit works in a single row and at eye level - an innovative display at the time. What is more, the works of artists of "major" and "minor" significance were exhibited side by side, and national boundaries were completely disregarded. Finally, Dreier's display included four rooms which reproduced domestic interiors - a reception, a library, a dining room, and a bedroom - showcased examples of modern painting, showing visitors how one might live with the abstract art that they found difficult and sometimes incomprehensible. She proclaimed, "Unless we have Art in home, we cannot learn its language.'"

In the six weeks that the International Exhibition was open, between November 1926 and January 1927, at least 53,000 visitors made their way through the Brooklyn Museum's doors to see it. While the exhibition was influential in introducing a new generation to modernism, the importance of the show has been overshadowed by the founding of the Museum of Modern Art in 1929, but in fact, the young curator Alfred Barr visited the Brooklyn show and took home many important lessons about the display of the new, radical art.

Late Period

In November 1929, the Museum of Modern Art opened its doors to the New York public for the first time. The relative effortlessness with which this new, well-funded museum had managed to establish itself, nine years after the founding of the Société Anonyme, produced in Dreier a feeling of injustice that she was never able to fully overcome. This sentiment was expressed in many occasions; in a 1936 letter to Duchamp, for example, she described MoMA as possessing "neither love nor intelligence regarding art." Indeed, as Liena Vayzman observes, "Dreier's vision of modernism, promulgated through the Société Anonyme's programs, was far more progressive and international than MoMA's, whose founders were predisposed towards French Post-Impressionism and figurative modernism."

A Country Museum of Visual Education, late 1930s

While Dreier's activities as commander-in-chief of the Société Anonyme are well documented, her Country Museum of Visual Education remains, as art historian Liena Vayzman points out is not as well known. Shortly after the International Exhibition of Modern Art ended, Dreier began contemplating the idea of giving the Société Anonyme a permanent home. Up until that point, the organization had operated from a number of rented offices in New York and borrowed exhibition spaces. Dreier thus imagined turning her Haven home into a Country Museum, describing her vision as one of "Art in the home and the garden...a part of everyday life...brought into the lives of our rural community, who can come and see it at leisure...without undue exertion." The artist had been treating her own homes as galleries for a long time; works of the art in The Haven embellished rooms filled with furniture in different styles, just as in the rooms she had presented in the Brooklyn exhibition. And so it was not difficult for her to imagine that The Haven could become a museum proper. "It would be a wonderful thing to have this house become a Museum," she wrote in a letter to Duchamp, "for it would mean that all the work of Love which I put into it will be preserved."

Dreier devoted a significant amount of work to realize her dream in the late 1930s. "Dreier's preparations," notes Vayzman, "included having an architect draft a plan of the property site as well as of the house itself ... On the back of a photograph of the front of the house Dreier noted: 'To the right the library / Below the garage to be turned into the Current Exhibition Hall...' indicating that she was giving thought to the layout of the museum." The artist also enlisted William Mathews Hekking, who was to be the museum's first director, to help her promote her proposal and raise financial support. In 1941, Hekking "authored a twelve-page proposal," as Vayzman documents, "outlining the project's aims, ultimate goal and financial strategies." Additionally, a great deal of thought went into the museum's educational activities, and Dreier also specified that the institution was to go beyond all others in its scope, presenting a series of "temporary exhibitions in many fields of human endeavor, including industry and science."

Dreier's financial situation at this point in time, however, made the realization of her museum difficult. Following the death of her parents in the 1890s, the artist had inherited the not-insignificant sum of $500,000. Yet, the crippling economic crisis of the 1930s coupled with the fact that Dreier had spent a large portion of her money on art meant that she needed external support to accomplish her goals. Having failed to secure the necessary funds for her museum, and after much deliberation, Dreier was, in the end, forced to accept Yale University's offer to take over the Société's collection and began moving it into the Yale Art Gallery in October 1941. "Your benefaction," Yale wrote in response, "will not only be of lasting usefulness to the University but to the entire country."

Dreier was already, at this point, showing signs of illness. While suffering from serious nonalcoholic cirrhosis of the liver, she lived for ten more years and died in 1952. In the aforementioned Yale University catalogue commemorating Dreier shortly after her death, Duchamp provided the dedication, praising Dreier as a "pioneer collector of modern art," someone with "infallible taste" and a "clairvoyant mind."

The Legacy of Katherine Dreier

While Katherine Dreier never achieved the recognition of her contemporaries as an artist, she was and is still considered today to be one of America's greatest collectors and educators of art in the 20th century. Following Dreier's death, art critic Aline Saarinen wrote, "She believed in reincarnation, but it would seem that her soul has not yet found its new lodging. Modern Art has known no other so fervent a propagandist." Indeed, Dreier organized the first American solo exhibitions of over 70 artists and contributed significantly to the understanding of a great number of others. As George Heard Hamilton noted, "Dreier belonged to the notable company of American artists and collectors who created the conditions for a serious and meaningful understanding of the modern movement in painting and sculpture....Without them the enthusiastic appreciation of modern art which now distinguishes American culture from that of other countries would have come much later and perhaps with less effect."

Influences and Connections

-

![Wassily Kandinsky]() Wassily Kandinsky

Wassily Kandinsky -

![Vincent van Gogh]() Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh - Gustaf Britsch

-

![Marcel Duchamp]() Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp -

![Man Ray]() Man Ray

Man Ray -

![Hilla Rebay]() Hilla Rebay

Hilla Rebay - Sheldon Cheney

Useful Resources on Katherine Dreier

- The Société Anonyme: Modernism for AmericaBy Jennifer Gross, ed.

- The Société Anonyme's Brooklyn Exhibition: Katherine Dreier and Modernism in in AmericaBy Ruth Bohan

- A to Z of American Women in the Visual Arts. USA: Facts on File, Inc., 2002By Kort, Carol and Liz Sonneborn

- "The Puppeteer of Your Own Past:" Marcel Duchamp and the Manipulation of PosterityBy Lee, Michelle Anne, (PhD Thesis)

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI