Summary of Hilla Rebay

A commanding figure, the artist, curator, advisor, and collector Hilla Rebay was consequential for the dissemination and popularization of modern art in the United States. Her role as advisor for Solomon R. Guggenheim and as the curator and director for the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (later the Guggenheim Museum) resulted in one of the best collections of modern abstract art in the country. Despite her efforts in promoting abstract art, Rebay's contributions have been overshadowed, or overlooked, in comparison to those made by the Museum of Modern Art and other collectors, but scholars and curators are beginning to rectify these omissions.

A deeply spiritual woman, Rebay felt that Non-Objective Art, her preferred term for abstract art, had the ability to heal an increasingly fractured world beset by world war, and she aimed to educate the masses in its powers. Drawing from esoteric religious beliefs and philosophical ideas of intuition, Rebay's interpretation of abstract art rankled many artists and critics alike, but she carried on some of the more consequential utopian beliefs that guided early avant-garde artists into the second half of the 20th century through her own artistic practice and her championing of abstract artists.

Accomplishments

- For Rebay, Non-objective Art was a spiritual cure for an ailing modern society mired in materialism and the growing commodification of culture. While technological innovations made modern life easier, Rebay felt that it came at the expense of cultivating a spiritual life that recognized the interconnectedness of people, nature, and the cosmos. Turning to forgotten religious ways and interior knowledge and intuition, Rebay believed that non-objective art could cultivate these areas, eventually creating a better, more peaceful world.

- Educating the layman in the ways of non-objectivity, of understanding the "eternal rhythm," was central to Rebay's project; through education, one developed the viewer's own intuition. It was only after living with the paintings that one could come to understand the beauty of them. Through a developed intuition, the viewer could vicariously experience the creation of the artist and experience the paintings as a salve for modern woes.

- Even if her spiritual ideas did not gain much traction in mid-20th century America, Rebay's patronage of European and younger American artists had enormous ripple effects for the promotion and collection of modern art. Through her work with Solomon R. Guggenheim, she turned many European artists into household names, and her artistic advice and financial support of young New York artists came at a time when many artists, such as Jackson Pollock, were struggling to make ends meet and to find their voice.

- Rebay's own artistic output of collages and paintings evince an intimate knowledge of many of the major avant-garde movements of the early 20th century, but her unique sense of balance and rhythm set her apart from her colleagues like Jean Arp and Wassily Kandinsky. Noticeably, while Rebay was devoted to and championed Non-Objective Art, many of her collages are figural in nature but still convey the spiritual essences so important to her.

Important Art by Hilla Rebay

Untitled (14H)

Rebay began creating collages around 1915 after being exposed to the medium by her then lover Jean Arp. For her, they became the perfect vehicle to express what she considered the purest form art should take: non-objectivity. This piece is one of her earliest experiments with the medium, and Rebay combines collage with watercolor drawing. Bits of colored paper and white shading create a dynamic, whimsical composition that is at once abstract and also suggestive of a rider on a horse, perhaps even the famed Don Quixote. According to art historian Brigitte Salmen, eventually her approach would mature and she would progress to creating "pure collages out of delicate strips and thick patches of colored paper. " In discussing these works, Salmen explains, "These mostly small-format works show an increasing freedom - in part owing to the technique itself. Over time Rebay developed a wholly personal collage style in which sparingly placed shapes float against empty, undelineated grounds. These carefully composed pictures present glowing colors sensitively attuned to one another. "

These early collage works also show the influence of German Expressionist Wassily Kandinsky. Having met him through Arp, she was impressed with his own dedication to non-objectivity. Kandinsky often described his paintings as visual manifestations of music, and in later pieces, she often titled her own creations with musical terminology as a nod to her mentor. According to museum director Karole Vale, Rebay was "inspired by the writings of Kandinsky, whom she described as 'a prophet of almost religious significance. '" For both Kandinsky and Rebay, art was a vehicle for spiritual enlightenment.

Collage and watercolor on paper, mounted on paper - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York

Paris through the Window

A celebration of duality that combines figurative and abstract aspects, Marc Chagall's painting can be read as a celebration of his new hometown of Paris while at the same time a longing for his native land of Russia. While representational images are present in this work, curator Jennifer Blessing suggests that it was Chagall's adoption of Robert Delaunay's Orphic Cubism to create the overlapping shapes of color that appealed most to Rebay and why she suggested that Guggenheim purchase it. Rebay's biographer Joan Lukach explains that Rebay reported to Guggenheim that "the Chagall was fine, Mrs. Guggenheim especially liked it" and added that she wished she could buy it for herself. Rebay encouraged Guggenheim to purchase several Chagalls over the years and became one of his great champions. He became the prominent artists in what Rebay called Guggenheim's "objective collection." According to Lukach, Rebay admitted that non-objective painting was "not at all [Chagall's] style. Still, I prefer Chagall to most of the non-objective paintings. "

The personal migration Chagall visually represented in this painting from his native Russia to France was not the only move he would make in his lifetime, and Rebay and Guggenheim played key roles in supporting him later in life. When World War II broke out, Chagall, as a Jew, felt he was no longer safe in Europe, and Guggenheim was instrumental in arranging his relocation to America in 1941. When he and his wife arrived, they stayed with Rebay at her home for a period of time, strengthening the bond between the curator and the artist.

Oil on canvas - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York

Composition pour Jazz

While Hilla Rebay's collaboration with Solomon Guggenheim began with the goal of helping him acquire an impressive collection of non-objective art, sometimes they went beyond this original mandate and acquired works in other styles, including, Albert Gleizes's Cubist painting, Composition pour Jazz. Rendered in simplified, broken down geometric forms, one can make out two musicians: one in a black suit holding a banjo, and the other perhaps a singer in a red hat. The loosely applied brushstrokes and unfinished quality of the painting mirrors the improvisational style of jazz.

Rebay had been friends with Gleizes since the late 1920s, and according to author Joan Lukach, in addition to liking his "very abstract" works "the two were in the same ideological camp, sharing the mystical view that 'non-objective' painting could be equated with an expression of the divine, and as such was a universal expression of religious man. Both believed, too, that when this connection was finally understood there would be peace in the world. "

Rebay introduced Guggenheim to Gleizes's art, and he purchased several over a period of years. This painting, while providing an example of Rebay's keen curatorial eye, more importantly provides proof of her interest in supporting the artists (often her friends) whose work she collected on behalf of Guggenheim. Lukach explains that Gleizes "was satisfied to have his paintings in a collection whose fundamental tenants he shared...." Despite Gleizes's reliance on the objective world to create his compositions, their spiritual kinship he shared with Rebay insured her continued support.

Gouache on cardboard, mounted on Masonite - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York

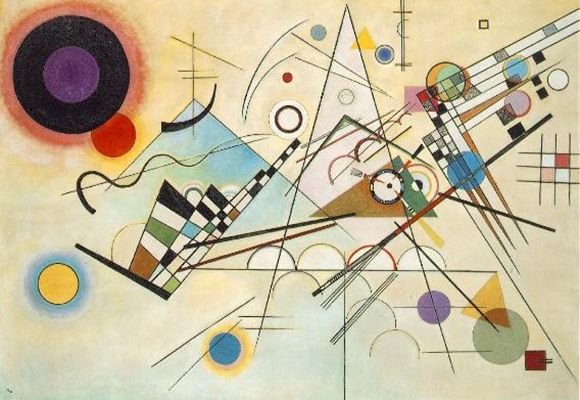

Composition 8

Hilla Rebay was drawn to the strong, non-objective compositions of Wassily Kandinsky's paintings. In Composition 8, circles and triangles, grids and lines, mosaics and squiggles pulse on the surface of the canvas. The dynamic composition is frenzied, but the repeating and familiar geometric shapes work to tone down the chaos. The generic title Composition calls attention to the abstract nature of the work but also has musical connotations as well. Many describe music as the most abstract of the arts, and Kandinsky often played with the connections and overlaps between music and painiting.

Rebay encouraged Guggenheim to begin purchasing works by Kandinsky, and his art became one of the cornerstones of the future museum's collection. The facilitation of the purchase of this work is just one small example of a myriad of actions she undertook to help nurture Kandinsky's career. She arranged the first meeting between him and Guggenheim in July of 1930 that would lead to Guggenheim also becoming one of the artist's biggest champions. Eventually, Rebay and Kandinsky had a falling out that lasted for several years, because she felt that he did not sufficiently support fellow artist (and Rebay's sometime lover) Rudolf Bauer. Despite her feelings, she continued to oversee the purchases of many of his paintings for several decades. Her final act on Kandinsky's behalf occurred less than a year after his death, when she planned a retrospective of his work at the Museum of Non-Objective Art in March of 1945 as a memorial tribute.

Oil on canvas - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York

T1

László Moholy-Nagy's T1 is a celebration of non-objectivity. In this complex work, Moholy-Nagy combines industrial materials (a kind of new, shiny black plastic) and techniques (airbrush), with avant-garde tactics (abstraction and collage). The airbrushed circles at the top and bottom of the work seem to float in front of the surface, while the smaller, central orb - made of silver paper - is collaged onto the plastic. Moholy-Nagy incised the straight line that connects two of the circles and then carefully painted it white. While non-objective art is sometimes considered disconnected from the concrete world we inhabit, Moholy-Nagy turns that assumption upside down by using non-traditional, industrial materials that firmly connect the non-objective and the objective.

Rebay was a strong advocate for Moholy-Nagy's art, and according to author Joan Lukach, he in turn "became one of Hilla Rebay's staunchest supporters and a true friend...[and] Rebay often sought his advice on a variety of topics. " Having first met in Berlin in the late 1920s, it is likely that Kandinsky alerted Rebay to Moholy-Nagy. After first seeing his work, Rebay was immediately impressed, and she directed Rudolph Bauer to purchase T1 for Guggenheim's collection. In time, Rebay and Guggenheim became avid collectors of Moholy-Nagy's work and exhibited them regularly at the museum.

Oil, sprayed paint, incised lines, and paper on Trolit - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York

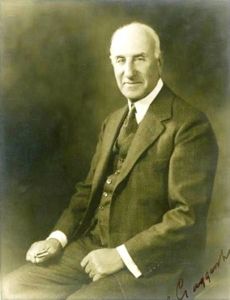

Solomon R. Guggenheim

Despite her championing of non-objective art, Hilla Rebay studied and displayed a skill in portrait painting, and she took on many commissions to support herself in the early years of her career. Her portrait of Solomon Guggenheim was without doubt her most important commission. It was arranged through his wife, Irene, who had seen an exhibition of Rebay's work and purchased two pieces. An impressive portrait, Rebay rendered her subject as a distinguished gentleman in a variety of shades of brown.

More importantly however, this painting captures a key moment in both the painter's and the sitter's life. It is likely that during this session, Rebay spoke at length with Guggenheim about non-objective art, and by the time the painting was finished, she had convinced him to start his own collection with her help. Shortly after, the pair would begin a series of trips to Europe to purchase paintings. More than a simple portrait, we see a visual manifestation of the start of a lifelong friendship and mutually beneficial partnership that would help to shape and promote modern art in the mid-twentieth century.

Oil on canvas - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York

Circular Forms

Robert Delaunay's painting, which is comprised of circles in a celebration of vivid colors, is an important example of the Orphism style which he developed. Hilla Rebay and Delaunay were kindred spirits and, as author Joan Lukach describes, theirs was "a meeting of like minds.... The friendship was cemented by a jointly held belief that abstract art was misunderstood and neglected, and by the common goal of forging an international alliance of non-objective artists.... " Rebay for her part helped achieve this goal by advocating that Solomon Guggenheim collect key artists of this style, including Delaunay.

Interestingly, in the beginning of their relationship, while she respected Delaunay, she considered him, according to Lukach, "primarily as a precursor of non-objective art." Later, however, as his works became more abstract, in part through his development of Orphism, he became a leader of non-objectivity. Circular Forms was among Delaunay's important paintings that Rebay advocated for to be added to Guggenheim's collection. Paintings like this support Rebay's belief that "non-objectivity will be the religion of the future.... Non-objective paintings are prophets of spiritual life. Those who have experienced the joy they can give possess such inner wealth as can never be lost. This is what these masterpieces in their quiet absolute purity can bring to all those who learn to feel their unearthly donation of rest, elevation, rhythm, balance, and beauty. " For Rebay and many of the artists she championed, abstract, or non-objective, art had the ability to heal the spiritual malaise that many blamed on modernity and industrialization.

Oil on canvas - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York

Invention (Composition 31)

A brightly colored non-objective painting, Rudolf Bauer's Invention (Composition 31) demonstrates how, according to art historian Karole Vail, "in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Bauer's work became more geometric and may have been influenced by the modernist and functional rigor of the Bauhaus and Russian Constructivism. " The sharply delineated forms stacked atop one another seem to float above the surface of the canvas and call to mind the Suprematist compositions of Kasimir Malevich.

For many artists and friends, Rebay's and Guggenheim's support of Bauer was incomprehensible for an otherwise astute collecting pair, as many saw his works as derivative and not very innovative. Rebay's support, in part, stemmed from her complicated romantic involvement with the cantankerous artist, but he also served as a prime example of what she could do with a Museum of Non-Objective Painting. Rebay's practice of turning to Bauer to facilitate purchases of paintings for Guggenheim when she could not be in Europe led to Guggenheim's strong support of Bauer as well. Most specifically, according to Vail, "In 1930, thanks in part to the purchase of his paintings by Guggenheim, Bauer opened his museum gallery Das Gestreich as a private salon where he exhibited his own and Kandinsky's works and which was inspirational for Rebay when she began to formulate her thoughts for a museum for Guggenheim's collection. " Despite their volatile relationship, Rebay's support was unwavering, and she chose this painting as the catalogue cover for the Museum of Non-Objective Painting's first exhibition which opened to the public on June 1, 1939.

Oil on canvas - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York

Rhythmic Delight

Hilla Rebay's painting Rhythmic Delight is a good example of her non-objective approach. In describing the work, museum director Karole Vail states, "Here she seems to have found the perfect balance, or 'interrelation of rhythm, line, balance, and measure' and 'cosmic inner order.'" The central orange circle, loosely painted, frames the intersecting horizontal and diagonal lines. The rhythmic squiggles emanating from the center have a musical and harmonic feeling. The colorful triangles along the outer edges of the canvas resemble elements of Rebay's earlier collages but also encircle the central shapes as if dancing in step around them, creating a pulsing dynamism.

For Vail, this painting, "one of Rebay's major paintings, executed when she was in her sixties, best conveys the 'diagram of the soul,' as Rebay described non-objective painting.... Rebay's paintings radiate masterly individuality.... She created her cosmos, her own ethereal world in them, blending geometric and organic elements in a single, integrated space and providing a vital sensation of energy. " For Rebay, the artist was a conduit for the divine, conveying the spiritual and the cosmic through their painting, and the dynamic and balanced composition of Rhythmic Delight speaks to her desire to express the interrelation at the heart of the world as she understood it. After her stint at the Museum of Non-Objective Art came to an end, Rebay devoted herself to painting again and to bettering the world.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Biography of Hilla Rebay

Childhood and Education

Hilla Rebay was born Baroness Hildegard Anna Augusta Elisabeth Rebay von Ehrenwiesen to an aristocratic German family that included older brother, Franz; mother Antonie von Eicken; and father, Franz Josef Rebay von Ehrenwiesen. Her father's career as a major in the Prussian army meant the family would move around a lot during her childhood, including to Freiburg when Rebay was only one and later to Cologne.

Unlike the fate of many young girls at the time, Rebay's progressive parents encouraged her early interest in art, as both were also fond of painting. They paid for her to have a private tutor, allowed her to study art during secondary school, and supported her attendance at the Cologne Kunstgewerbeschule.

Early Training

Committed to pursuing a career as an artist, Rebay moved to Paris in 1909 where she enrolled in the Académie Julian where she honed her portraiture skills, which helped support her before she moved to more abstract work. She also took evening classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, where, importantly, she began associating with other students who followed Theosophy, a belief system that attempted to fuse together aspects of several world religions. While Rebay had first been exposed to the mystical religion as early as age fourteen, it was here in Paris with fellow students that she became serious about the study. Just as avant-garde artists such as Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian connected their abstract compositions to spiritual goals, Rebay saw a deep connection between the two. She wrote to her mother, "The deeper I delve into it, the happier it makes me; everything becomes clear, especially that spiritual sensitivity necessary for an artist to experience nature and to feel one with it. " Rebay began to link her art to religion and according to art historian Joan Lukach, "[H]er religious conviction became entwined with her aesthetic credo, art constituting for her a form of religious expression."

A year in Munich in 1910 for more study followed by a return to Paris in 1911 brought Rebay into contact with modern art and artists. In the fall of 1913, she moved to Berlin, where she began to focus seriously on her art, only taking a brief hiatus during the start of the first world war when she returned home to her parent's house in Hagenau and took a job as a nurse.

Mature Period

A key figure in Rebay's progression into modern art was the Dadaist Jean (Hans) Arp, with whom she began a romantic relationship in 1915. He introduced her to the work of artists, including Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky, and importantly, his work with collage would inspire Rebay's own works in the medium as well as her start in non-objective paintings, which she began creating around 1917. Rebay explained his impact on her, writing, "He made a deep impression on me. I first took it for love - because it was so new and pure and wonderful to be with him - but I am unable to love - there is always something that makes me crazy. "

Rebay's relationship with Arp ended in the spring of 1917, but not before he introduced her to artist Rudolf Bauer. Sharing similar ideas for the future direction of art, the two began a relationship. While it would last on and off for several decades, it would be a difficult one for Rebay. She would ardently defend him and his art despite his often mentally and verbally abusive attitude towards her, his jealousy over her work and any success she might receive, and the fervent pleas from friends and family to abandon him.

Rebay quickly began to establish a name for herself, exhibiting her collage works and paintings in key gallery exhibitions throughout Europe. In 1920, she, along with Bauer and Otto Nebel founded the Die Krater art group. The group's aim, according to author Brigitte Salmen, was to "construct the absolute church as a spatial concept combining the museum, the music hall, and the gallery that automatically does away with nuisance of exhibitions, art dealers, and agents. Die Krater's activities continued for only a few years and had little public impact, but it was the first artist group to propose a museum of non-objective art. "

Between 1922 and 1925, Rebay fell ill, suffering from issues with her nerves that were in large part due to her difficult relationship with Bauer. In these years, she had little work shown and is believed to have spent time in a sanatorium.

Looking for a change, she decided to leave Europe in January 1927 and start a new life for herself in America. Settling in Manhattan, she quickly ingratiated herself into the art scene and supported herself through portrait commissions, designing posters, and giving art lessons. Her most notable student was a young Louise Nevelson. Rebay also began exhibiting her work, including in a show at New York's Galleries of Marie Sterner, where socialite Irene Guggenheim purchased two of Rebay's works. Irene also commissioned Rebay to create a portrait of her husband Solomon R. Guggenheim, an enormously wealthy businessman who made his fortune in mining and who was the uncle of Peggy Guggenheim, who was also beginning his education in modern art.

This one portrait commission would fundamentally alter the direction of Rebay's career, as it is believed that it was while working on his portrait that she first acquainted Guggenheim with non-objective art. By the time Rebay completed the painting, she had convinced him to start his own collection with her help. While some have tried to imply a romantic relationship existed between the two, there is no evidence of such a relationship. Instead, this meeting was the start of a professional partnership and friendship between Rebay and Guggenheim that would last the rest of their lives.

In May of 1929, Rebay made her first trip to Europe with Guggenheim and his wife to begin purchasing works of modern art. It is also at this time that she engaged the help of Bauer to make purchases on her behalf for Guggenheim when she was back in the states. Rebay's keen understanding of modern art and shrewd eye led to Guggenheim acquiring a vast and important collection of works by artists, including Alexander Calder, Marc Chagall, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Wassily Kandinsky, Fernand Léger, László Moholy-Nagy, often after studio visits with the artists themselves. While a large portion of the works Guggenheim purchased could be seen in his apartment at the Plaza Hotel in 1930, Rebay craved a more public space, and by 1933, she convinced Guggenheim to build a museum which would provide a permanent home for his art. To draw attention to this plan and gather support for their endeavor, the pair begin mounting exhibitions of the collection in venues across the United States. For the first exhibition at the Gibbes Memorial Art Gallery in Charleston, South Carolina, Rebay wrote the essay, "Definition of Non-objective Painting," for the exhibition catalogue. Helping to promote the importance of this art, she wrote, "Because it is our destiny to be creative and our fate to become spiritual, humanity will come to develop and enjoy greater intuitive power through creations of great art, the glorious masterpieces of non-objectivity. "

In 1937, Guggenheim created The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation which Rebay's biographer Joan Lukach explains was "for the 'promotion and encouragement of art and education in art and the enlightenment of the public.' One of the foundation's principal objectives would be to establish a museum, the nucleus of which would be Guggenheim's collection of modern paintings. " He publicly announced Rebay's partnership in this endeavor by naming her curator of the collection. According to Lukach, from this point forward "Rebay devoted the greater part of her life to The Guggenheim Foundation, of which she was also made a trustee in 1938. "

On June 1, 1939, Guggenheim's museum opened in a location on East Fifty-fourth Street, which was once a showroom for automobiles; its name, a joint decision by Rebay and Guggenheim, had a compound title: "Art of Tomorrow," the Museum of Non-objective Painting. Rebay was named director and considered a large part of her job to educate the public on the importance of non-objective art. Artists started sending her their works for her review and critique. Lukach explains that "if the effort, no matter how halting, were sincerely non-objective in intent, Rebay maintained a personal interest in the painter's development. " Through the foundation she also granted artist scholarships and supported others by sending them supplies from a line in the museum's budget created by her specifically for this purpose. Others were offered part-time jobs at the museum, which helped provide funds for them to continue their work. Most notably Jackson Pollock began working there in May 1943 as a maintenance man. Ultimately Rebay did not get on with him, most likely in large part because she never truly embraced Abstract Expressionism, and he left the museum after receiving a contract to show his work with Peggy Guggenheim at her Art of This Century Gallery; but Rebay still played a part in nurturing his career.

This was not the first time Rebay and Peggy Guggenheim had found themselves disagreeing with each other. Rebay and some of her colleagues had, for a period, considered establishing a non-objective art center in Paris; however, in 1940, friends warned her of Peggy Guggenheim's efforts to open her own art gallery there. Rebay felt that Peggy was trying to build off the "Guggenheim" name, which had considerable power in the art world due to her uncle's and Rebay's efforts; according to Lukach, many artists that Rebay supported feared that Peggy's more Surrealist inclinations would derail the progress of non-objective art and would confuse the public. Ultimately World War II altered the focus of both parties and neither opened a European space. Instead, they turned their attention to the states, with Peggy founding Art of This Century gallery in October 1942 and Rebay and Solomon continuing their own New York pursuits, ultimately leading to their own grand museum.

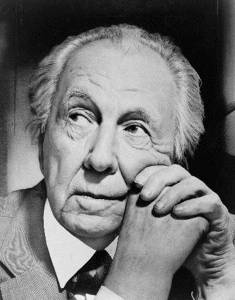

Soon, Rebay began to formalize plans to create a permanent building to house Guggenheim's collection. Believing strongly that an American architect should be given the commission, she wrote to Frank Lloyd Wright to determine his interest. According to Lukach, "In her first letter she explained exactly what she wanted: a building in which to present the paintings - a temple and a monument. " After Wright agreed, the pair began what would be a lifelong friendship, and Wright later praised her "continuous expenditure of energy" and called her "a super-woman. " While both knew their minds and could be described by some as having difficult personalities, they shared an excitement and passion for modernity and the potential greatness of their future museum. Rebay, for instance, was the one to suggest a circular building, which Wright supported, but Lukach explains how there were also some disagreements to which Rebay held strong and got her way, rejecting Wright's idea for a red marble exterior and a roof garden. It would take fifteen years from the start of their collaboration until the new building opened to the public, and in the interim, the collection was moved to a temporary building, a townhouse on Fifth Avenue, in November 1948.

Rebay's support of artists was not deterred by the outbreak of World War II. Many of her and Guggenheim's friends, the artists that formed the core works in their museum, were in danger during the war. They offered some like Marc Chagall and Rudolf Bauer aid in leaving Europe. Both even stayed for a period at Rebay's newly purchased Connecticut home when they first reached America. Unfortunately, Rebay also suffered during the war. Denied American citizenship in 1938, Rebay felt the discrimination resulting from the rising fears and distrust of Germans during this time despite the fact that she had long spoken out against Hitler and no longer felt safe visiting family in Germany.

On October 12, 1942, the federal government named her an enemy alien and took her into custody. According to Lukach, "For eight weeks she was held for investigation with other German citizens.... The government's investigation centered on charges that she was hoarding since she kept large quantities of food at her house in the country. Her explanation was that from the time she moved into the house, before rationing had begun, she had kept a full larder.... Not only did she provide for her staff, but in her position as head of a museum she was often required to entertain.... The Connecticut Office of Price Administration found her explanation reasonable. She gave her coffee and sugar to the Red Cross, and the case against her was dropped. "

During this difficult time, the attack she felt most personally was from Bauer, who tried to take over her role in the museum during her confinement and who may well have been responsible for some of the most vicious rumors about her. She would later have to defend herself in front of the foundation's trustees and answer to charges that she was against the United States and against groups including Catholics, Jews, and African Americans. While she succeeded in defending herself against these claims, her relationship was never the same with Bauer and ended completely when he married his housekeeper in 1944, permanently breaking Rebay's heart. She was not without support at this time, and throughout this entire ordeal, Guggenheim fiercely defended her as did Frank Lloyd Wright. Cleared of all charges and her job intact, Rebay received the greatest prize she could have hoped for when she was awarded United States citizenship on January 9, 1947.

Later Period

With the war over, Rebay threw herself back into her work including a return to a focus on the new building design. She also led an effort to restore the growth of modern art in her native Germany, which Hitler had tried to destroy during the war. To this end, according to Lukach, "[S]he developed a sense of urgency about the need to aid surviving or prospective non-objective artists, and through The Guggenheim Foundation began to send parcels to anyone who qualified for either of these categories. "

Knowing he was ill, Guggenheim had written a letter, praising Rebay and expressing his hope for her future at the museum, including "It is my further wish that during the lifetime of Miss Rebay the Foundation accept no gifts and make no purchases of paintings without her approval.... " However, as he did not make the letter a formal legally binding part of his will, her future was not guaranteed. After Guggenheim died, on November 3, 1949, his first successor, his son-in-law Earl Castle-Stewart honored his wishes and Rebay maintained her control. However some of the trustees did not trust Rebay and according to Lukach, her "operating budget was tightly reined, and her purchase funds were substantially reduced. " A critic, Aline Bernstein Saarinen wrote a column in the New York Times in 1951 calling for Rebay's firing and that the works be given to the Museum of Modern Art instead of finalizing a new museum building. After Castle-Stewart's death in 1952, Guggenheim's son Harry came into control, and Rebay lost all of her support. Growing dissent among critics and artists about Rebay's spiritual interpretation of non-objective art as well as her increasing anxiety and mental state all contributed to her ouster from the museum. Using her poor health as the reason, Rebay stepped down as the museum's director in March 1952, although she continued on as a trustee. A further insult was forced on Rebay when the name of the museum was changed to the "Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum" removing all mention of her beloved legacy of non-objective art. Sadly when the new museum opened in October 1959, Rebay was not invited. Shortly after, she was removed from her posts as trustee and director emeritus and some affiliated with the museum would work for years to downplay her role in its history.

The last decade of Rebay's life, spent without any connection to her beloved museum, pushed her towards new pursuits. She spent a lot of time traveling, including a trip around the world in 1955. She also returned to her studio, where she created more works and participated in exhibitions. In addition, her personal art collection, amassed over the decades spent helping Guggenheim build his, had become quite impressive and a selection of German museums hoped she would make a significant gift to them in honor of her heritage. This never happened, however, and instead, in 1967, she made the decision to establish the Hilla von Rebay Foundation which had a guiding mission to, in her words, "foster, promote, and encourage the interest of the public in non-objective art. " It was her hope that upon her death her Connecticut home would be used as an art gallery, education center, and home to her collection.

Suffering from heart and circulatory issues, Rebay died at the age of seventy-seven. Sadly after her death, her final wishes were not honored and according to Lukach, "[T]he trustees of her foundation agreed that The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum should care for the paintings, the library, and the more than ten thousand letters and other documents from four thousand individuals.... " Ironically, the museum administration that had recently forced her out of their employ ended up benefitting from her impressive collection of non-objective art.

The Legacy of Hilla Rebay

Hilla Rebay left a profound legacy on the art world. Playing a key role in shaping modern art of the twentieth century, she was among the first artists to use the term "non-objective" to describe the abstract art that she and her colleagues were creating. She made it her life's mission to further the importance of non-objective art and to educate others about this movement. Her greatest achievement in this effort was her success in convincing Solomon R. Guggenheim to collect non-objective art. In doing so, she helped support the career of many artists and set in motion the building of a collection that would become the foundation of one of the world's greatest modern art institutions. Her promotion of non-objective art filtered through all she did - her mentorship of young artists, her distribution of scholarships, and finally her own foundation.

Any discussion of Rebay's legacy on the art world, however, would be underserved if a mention of her own work as an artist was not included.. According to museum director Karole Vail, "Rebay's reputation as a committed proponent of non-objective art, an advisor to Solomon R. Guggenheim, and the founding director of the Guggenheim Museum, has overshadowed her accomplishments as an artist, but her elaborate and adventurous work provides clear evidence that she was an original artist with a singular voice and an unusual freedom of expression.... " Her influence can even be felt on contemporary artists, including Carter J. Thomas and Laurie Fendrich, who according to art historian, Robert Rosenblum, "are revisiting the style of the 'art of tomorrow' in its postmodern guise of 'neo' and 'retro. "

Influences and Connections

-

![Hans Arp]() Hans Arp

Hans Arp -

![Albert Gleizes]() Albert Gleizes

Albert Gleizes -

![Wassily Kandinsky]() Wassily Kandinsky

Wassily Kandinsky -

![László Moholy-Nagy]() László Moholy-Nagy

László Moholy-Nagy - Rudolf Bauer

-

![Solomon R. Guggenheim]() Solomon R. Guggenheim

Solomon R. Guggenheim -

![Frank Lloyd Wright]() Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright -

![Katherine Dreier]() Katherine Dreier

Katherine Dreier ![Felix Feneon]() Felix Feneon

Felix Feneon

-

![Art Nouveau]() Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau -

![Futurism]() Futurism

Futurism -

![Modernism and Modern Art]() Modernism and Modern Art

Modernism and Modern Art - Non-Objective Art

-

![Ellsworth Kelly]() Ellsworth Kelly

Ellsworth Kelly ![Ilya Bolotowsky]() Ilya Bolotowsky

Ilya Bolotowsky![Max Bill]() Max Bill

Max Bill- Alice Trumbull Mason

- Oskar Fischinger

![Charles Atlas]() Charles Atlas

Charles Atlas- Karl Nierendorf

- Henri-Pierre Roché

-

![Expressionism]() Expressionism

Expressionism -

![Orphism]() Orphism

Orphism - Non-Objective Art

Useful Resources on Hilla Rebay

- Hilla Rebay: In Search of the Spirit in ArtOur PickBy Joan Lukach

- The Museum of Non-Objective Painting: Hilla Rebay and the Origins of Solomon R. Guggenheim MuseumBy Tracey Bashkoff