Summary of Orphism

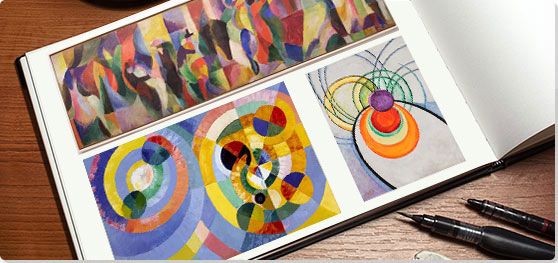

Breaking free from Cubism to embrace brilliant color and representations of time and experience, Orphism introduced non-objective painting to French audiences. As one of the earliest styles to approach complete abstraction, Orphism brought together contemporary theories of philosophy and color to create works that immersed the viewer in dynamic expanses of rhythmic form and chromatic scales. Less than a long-term, cohesive movement, however, Orphism was a loosely bound group of artists with the common goals of moving beyond concrete reality to present a flowing vision of simultaneity and flux. It flowered briefly in the years leading to World War I, before fading with the rise of the war in 1914.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- From its inception, Orphism was interdisciplinary, integrating Henri Bergson's philosophical theories about time and experience with poetic experiments with symbolism and abstraction. The poet Guillaume Apollinaire coined the name, after the Greek god Orpheus who was renowned for his musical talents. Indeed, the artists of Orphism aspired to the levels of abstraction possible in music, where sounds were able to evoke emotions and experiences despite being disconnected from the real world. The Orphists arranged color harmonies after the model of musical scales and chords.

- Orphism was based in Cubism, but with a new emphasis on color, influenced by the Neo-Impressionists and the Symbolists. Unlike the monochromatic canvases of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, the Orphists used prismatic hues to suggest movement and energy. In emphasizing the sensory and intuitive, they provided radical new possibilities for the abstractions of Cubist ideas and created another path to the progression of modernism.

- Although no one is certain who created the first non-objective painting, the Orphists have a claim to this distinction. Between 1910 and 1912, several artists painted abstract canvases, including the Expressionist Wassily Kandinsky and the American Arthur Dove, although František Kupka, Sonia Delaunay, and Robert Delaunay all created works that are potential contenders. The competition is complicated: Sonia's abstract blanket design, which inspired her and her husband to paint abstract compositions, was not initially considered a work of fine art and both Robert Delaunay and Kupka painted designs based on subjects, making them not quite non-objective. Still, their inclusion among this elite group testifies to the importance of their avant-garde experiments.

- Believing that the color harmonies and radiating forms of Orphism represented universal energies, the artists moved beyond oil painting to experiment with more popular outlets. From poetry to design, some of the movement's most visible products were Sonia Delaunay's forays into fashion and décor. In fact, the movement's earliest and most daring abstract work was a textile created by Sonia, which then inspired painterly abstractions by her husband, Robert. Their broad definition of artistic production helped cultivate the idea of art as a total environment and further popularized collaborations between artists and industry.

Artworks and Artists of Orphism

The City of Paris (La Ville de Paris)

Delaunay considered this monumental painting (13 x 9') a turning point in his work, and suggested a larger, metaphysical continuum of time and experience. Intended to be a visual manifesto, he incorporated elements of modern fragmentation while juxtaposing them with classical allusion and historical scale. The work combines fragmentary views of Paris and elements of its history, beginning on the left with the Quai du Louvre, representing ancient Paris, and, ending on the right with the Eiffel Tower, symbolizing the city's modernity. Reflecting Orphism's emphasis on depicting modernity's simultaneous states of being, this work conveys the fleeting sensations of modern life in Paris. He had first explored imagery of the Eiffel Tower in 1909, and it was to become a central symbol in his work. Delaunay also added the symbolic layer of the three women; their fragmented figures represent Paris of the past, the present, and the future while alluding to the Greek myth of the Judgment of Paris. The women were partly inspired by a wall painting of the three graces from ancient Pompeii.

The large scale and the use of allegorical figures show Delaunay intended the work as a kind of tour de force, proclaiming his departure from Cubism with its exhibition at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants. The brilliant Orphist color palette, based in contrasting primary and secondary hues, creates a sense of vibrant movement and simultaneous sensation. Delaunay believed this offers another level of significance, beyond concrete reality. As Apollinaire wrote, "more than an artistic manifestation. This picture marks the advent of a conception of art lost perhaps since the great Italian painters...he sums up, without any scientific pomp, the entire effort of modern painting."

Oil on canvas - Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

Couverture de Berceau

The patchwork blanket, made of 70 triangular and rectangular pieces of cloth, is arranged in contrasting patterns along a roughly designed grid, creating a softly harmonious but dynamic effect. The dominant horizontal and vertical lines are counteracted by triangular patches, which introduce subtle diagonals to provide a sense of vibrant movement. The arrangement of black rectangles, green triangles, and small vertical rectangles of yellow in the center of the work create a sense of depth, as if looking into deeper space, yet the textile remains an insistently flat surface, creating visual tension between illusion and reality.

Although this work would serve as a foundation for Orphism, its origins were relatively humble. Sonia Delaunay explained that, "About 1911 I had the idea of making for my son, who had just been born, a blanket composed of bits of fabric like those I had seen in the houses of Russian peasants. When it was finished, the arrangement of the pieces of material seemed to me to evoke cubist conceptions and we then tried to apply the same process to other objects and paintings." The quilt's status as a domestic object and not fine art made it more possible to experiment with pure abstraction; the stakes were lower and it was acceptable to pursue patterns and colors in a purely decorative fashion.

This early Orphist work informed the movement's theory and practice, as it inspired her husband's series of Simultaneous Windows. In truth, Sonia's work is the more advanced: Robert's series retained some figurative elements, while the blanket is totally an abstract arrangement of colors, shapes, and lines. Despite its utilitarian origins, once her son had outgrown the quilt, Sonia framed it and exhibited it among her earliest abstract tableaux.

Cloth quilt - Musée d'Art Moderne

The Rhythm (Adam and Eve)

This work, depicting Adam and Eve in Paradise, marked the young Baranoff-Rossiné's debut as a modernist and demonstrates his early adoption of Orphist ideas. Like Delaunay, he intended the painting to make a grand demonstration of the meaningful potential of harnessing color and form to make meaning; he incorporated traditional symbolism, quoting Old Master works, to underscore its ancestry. Indeed, Adam's posture and profile alludes to Albrecht Dürer's 1504 Adam and Eve, but, unlike Dürer, the artist portrays Eve as a supine and seductive being, accompanied by a cat which symbolizes sexuality, drawing from more recent fin-de-siècle iconography of the femme fatale (Adam is attended by a faithful hound). A solar disk swirls at the center of the canvas, and six rings radiate around it, representing the Biblical six days of creation. The vegetation growing out of the third ring creates a sense of vibrant growth, in which can be seen fragmentary and amorphous animals.

Baranoff-Rossiné's s use of the allegorical and the cosmological was influenced by Delaunay's allegorical figures in La Ville de Paris, as his solar disk alludes to his mentor's emblem. Nevertheless, the artist uses the allegorical with a different intent, creating not the sensation of modern reality, but a symbolic paradise, a world newly generated out of the rhythm of light, where the dynamic solar disk represents the eye of God.

In 1910 the young Ukrainian artist moved to Paris where he met the Delaunays, who became his mentors at the moment when they were developing the theory and practice of Orphism. Showing his interest in Orphic color and dynamic structures, this painting debuted at the 1913 Salon des Indépendants, the height of the movement's popularity.

Oil, pencil and crayon on canvas - Private Collection

Simultaneous Windows on the City

This view of Paris, centered on the Eiffel Tower, recognizable as a green silhouette, appears throughout Delaunay's Simultaneous Windows series. Conveyed in translucent, overlapping, and contrasting color planes, the window serves as a framing device and a way of overlapping interior and exterior spaces in the painting. The influence of Symbolism can be seen in the artist's use of the Eiffel Tower as a symbol of modernity, and also in his use of windows, as Symbolism used images of glass to symbolize the connection between internal and external realities. Although the work was based on a photographic postcard, it also shows the influence of Sonia Delaunay's quilt in its grid-like pattern of rectangular and triangular planes.

The Simultaneous Windows paintings were a breakthrough for the artist, helping to differentiate him from other Cubists; as he explained, they were "in reaction to the academicism and confusion of early Cubism." While the influence of Cubism can be seen in the use of multifaceted planes, his emphasis on structuring the work through blocks of vibrant color, rendered here in vibrant translucencies was radically different from his colleagues. The name of the series refers to Chevreul's idea that the eye perceives contrasting colors simultaneously and it also references Bergson's ideas on the structure of time and experience as a continuum. Looking at the work, the viewer's focus shifts between the forms and the planes of color, drawn by the relationships between the hues. Color becomes structural in the work, and the painting itself becomes a window, where all the elements are present simultaneously, but harmoniously.

Oil on canvas - Kunsthalle Hamburg, Germany

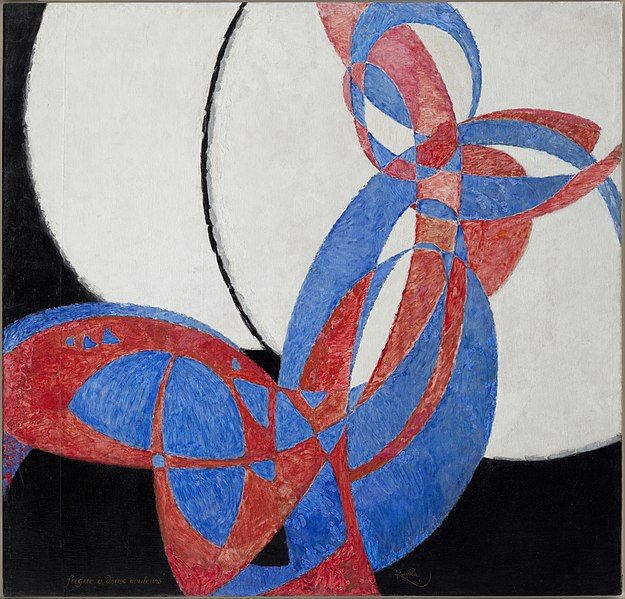

Amorpha, fugue en deux couleurs (Fugue in Two Colors)

In this work, the artist uses a highly simplified palette of blue, red, black, and white, combined in a series of arabesque patterns. The simplicity of the work is, however, misleading; Kupka made 27 preliminary studies for this work. His earliest sketches from 1907-1908 were representational, depicting a girl making a circling motion with a ball in her hand. Over time, he focused solely on her movement making the result increasingly abstract. To a viewer unaware of the preliminary drawings, the painting would appear completely non-objective.

Indeed, when the work debuted at the 1912 Salon d'Automne, it generated controversy as the first abstract work shown in Paris. Its limited color palette was also shocking, as Kupka interwove red and blue in curvilinear ribbon patterns to give the colors the quality of melodies in a fugue. The red and blue arabesque's fluidity between plane and line and between background and foreground has the effect of movement and depth. As the title suggests, he felt that pure painting was analogous to music as "the sounds evolve like veritable physical entities, intertwine, come and go."

Oil on canvas - National Gallery in Prague, Czech Republic

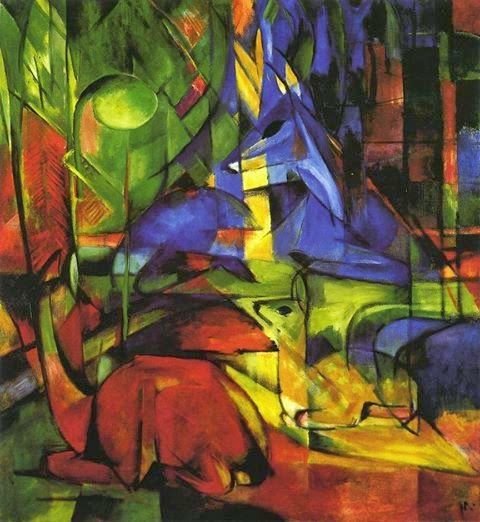

Lying Bull

Robert Delaunay joined Der Blaue Reiter in 1911 at the invitation of Wassily Kandinsky. Orphists and the Expressionists both argued for the evocative and dynamic use of color and form, thus their approaches to painting were highly compatible, cross-pollinating between Delaunay and some members of Der Blaue Reiter. And Marc, along with Paul Klee and August Macke, visited Delaunay's Paris studio in 1912.

Marc's work primarily focused on animals, which often represented spiritual qualities he found lacking in the modern world. Centered in the canvas, the bull reflects both Kandinsky's color theory that blue had the highest spiritual resonance, and Marc's own association of the color with masculinity. Reflecting the influence of Orphism, Marc presents the animal and its surroundings in a rectangular pattern, suggesting a grid of overlapping planes. A structure of opposing colors, particularly around the bull's head and body, create a feeling of harmony between the creature and its environment. The contrasting curvilinear shapes evoke the natural and organic world while contributing to a sense of energy, that is powerfully at rest.

Tempera on paper - Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany

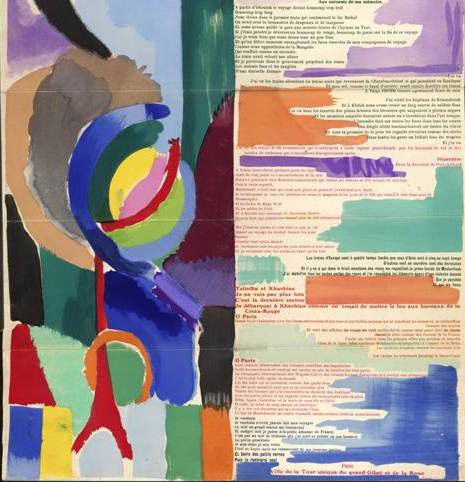

La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France

Demonstrating Orphism's interdisciplinarity, this work was a collaboration between Sonia Delaunay and the poet Blaise Cendrars. More than just an illustration, Delaunay's swirling colors create an analogue to the poem, which describes a journey on the Trans-Siberian Railway during the Russo-Japanese War and the Russian Revolution of 1905.

Marketed as the "first simultaneous book," the work begins at the top with a Michelin railway map of the journey; it ends with an image of the Eiffel Tower in red. The tower was integrated into the construction of the work, as well: the poem was printed on four panels of paper that were accordion-pleated to form a small booklet of 22 pages. The initial print run of 150 copies, if all booklets and pages were laid end to end, they were calculated to measure the exact height of the Eiffel Tower.

A number of scholars have questioned whether Cendrars ever took his journey, or if it was entirely mythical, meant to rival the great French poet, Arthur Rimbaud's imaginative journey in L'bateau ivre, (The Drunken Boat). When asked about the actuality of the trip, Cendrars would only reply that accuracy was unimportant, what mattered was that he had made the reader experience it. Delaunay's painting was integral to that sensorial quality; the two collaborators explained, "The simultaneous contrast of colors and the text form depths and movements of novel inspiration."

Apollinaire introduced Cendrars to the Delaunays in 1912 and, by autumn, Cendrars was staying with the couple. He credited the development of his poetic practice to their idea that, as Robert Delaunay said, "Everything is color in movement, depth." Accordingly, the poet incorporated the visual into his text, using 12 different fonts, different sizes of text, and colored font. In turn, Sonia Delaunay wanted to translate the words into color, and so used irregular shapes of contrasting color to create a feeling of speed and disorientation. The reader's eye is constantly moving between the poem's dark subject matter and a brilliant field of color. Cendrars later described the work as "a sad poem printed on sunlight."

Illustrated book with watercolor applied through pochoir and relief print on paper - Princeton University Art Museum

Le Bal Bullier (Bal Bullier)

The first work to explore Orphism's use of contrasting colors on a monumental scale, this twelve-foot long painting depicts a view of dancers and dancing couples under the dome lights of a Parisian dance hall. The dancers are fragmented into bright abstract areas of color, and the contrasts of red against green, purple next to yellow, create a swirling and energetic effect. The background is depicted in larger swathes of contrasting color, and the dome lights, haloed with concentric rings, resemble the emblematic solar disks of Robert's contemporary paintings and point toward Sonia's subsequent abstraction, Prismes electriques.

The Delaunays frequented the Ball Bullier dance hall, a gathering place where the literary and artistic avant-garde would convene - and dance the tango, the latest craze. Here, Sonia draws upon her experience to capture the energy and excitement of the scene and the dancers, swirling through a world of inner and outer sensations. Her triangular and rectangular planes are not uniform but curved, resembling pieces of fabric; the effect of this curvilinear approach is rhythmic, so that the whole room seems to dance.

Oil on paint on mattress ticking - Collection of Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

Prismes electriques (Electric Prisms)

This work is electric with color, radiating from the two large circles at the center. The concentric rings and arcs are depicted in contrasting primary and secondary colors that overlap and become prismatic. In the rest of the painting, partial circles like halos cast by a light are broken by geometric patches that convey glimpses of the sidewalk beneath, at the lower right, and a building in the center left. This fragmentary landscape has been engulfed and dwarfed by a larger dynamic realm of sensorial color and pulsating form.

The work builds on the roots of Orphism found in Robert Delaunay's earlier Neo-Impressionist Paysage au disque (1906-1907). In that painting, he adopted an icon of the sun, represented by a disk with concentric rings, as a personal emblem. The radiating orbs of Sonia's painting, nearly a decade later, demonstrate the couple's enduring desire to use color to structure painterly space in order to express contemporary experience. In this example, both Sonia and Robert found the newly installed electric streetlights in Paris to be fascinating; here she conveys not only the glow of the lamp but the exciting sensations of new technologies and frenetic nightlife.

Oil on canvas - Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

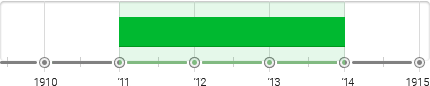

Beginnings of Orphism

Around 1911, the theory and practice of Robert and Sonia Delaunay began to converge with the experimental work of František Kupka, giving birth to Orphism. The notion of Orphism was popularized by Robert Delaunay's influential article of 1912, "La lumière" and Guillaume Apollinaire's description of "Orphic Cubism" in his 1913 writings on modern art. The collaborations between Robert and Sonia Delaunay broadened the range of Orphism beyond the art world. The Delaunays would become most closely associated with Orphism, even though Kupka received some of the earliest acclaim for his advocacy of pure painting, abstract and free from any need to be descriptive. This non-objective ideal broke with even the most radical painters of the time, who abstracted from nature, but still worked from identifiable sources.

Robert Delaunay called the new movement, Simultanisme (Simultanism), or "Simultaneous Contrast." The term, Simultanism, was borrowed from Henri Bergson, a French philosopher who valued intuition over intellect as a way of understanding the universe. In particular, Bergson's notion of la durée, the constant flux of time and reality, was highly influential to artists. If modern consciousness was indeed a flow of simultaneous states of being, it was false to present that reality as one frozen image; more truthful was the suggestion of reality through an experiential display of line and color. Delaunay argued that art could best achieve the sensations of modernity by using contrasting primary and secondary planes of color, using color itself to structure the painterly space.

In this interest in the formal elements of painting, color, and shape, Delaunay was influenced by Neo-Impressionism. He had painted in the Divisionist manner (a style within Neo-Impressinism) from 1905-1907, following after the example of Georges Seurat or Paul Signac. Like them, Delaunay was deeply impressed by Michel Eugène Chevreul's De la loi du contraste simultanée des couleurs (On the law of the simultaneous contrast of colors) of 1839. This text had been central to the Neo-Impressionists for its discovery that colors appeared differently when placed adjacent to other colors; this was the bedrock for Divisionist brushwork, which juxtaposed small flecks of pure color to create forms. Delaunay also drew from another important Neo-Impressionist source, Charles Henry, who had argued that color, line, and form had abstract emotional associations, independent of the subject being depicted. After abandoning the Neo-Impressionist style, Delaunay remained committed to color theory, carrying its principles forward into Orphism.

Simultaneous Windows

Robert and Sonia Delaunay jointly progressed towards Orphism at the same time; he considered his Simultaneous Windows series to be a breakthrough, completing these paintings while Sonia created her Contrastes Simultanés. Robert explained "I had the idea for a kind of painting that would depend only on color and its contrast but would develop over time, simultaneously perceived at a single moment." his work remained connected to a concrete source of inspiration (for example, the fragmented image of the Eiffel Tower appears in all but the final paintings of the series); at the same time, Sonia's work was completely abstract. The impact of Henri Bergson's theories on la durée and simultaneity are evident from the titles of these works, as well as their effort to suggest an expanse of time instead of one frozen moment.

In 1912 Frantisek Kupka exhibited two abstract works, Amorpha: Fugue in Two Colors and Amorpha: Warm Chromatic (both from 1910-1911), calling them "his painter's credo." His work was inspired by Notre Dame's stained glass windows, which he described as the, "vertiginous musicality of color." He was also interested in the mystical correspondences between painting and spirituality. Many of his titles use musical terms, as he intended for the viewer to look for correspondences between painting and music. This would become a common theme in Orphism, which sought to evoke temporal and spiritual sensations through abstract means, just as music was able to accomplish. In this vein, Kupka argued that chromatics were structural, akin to chord structures in musical composition.

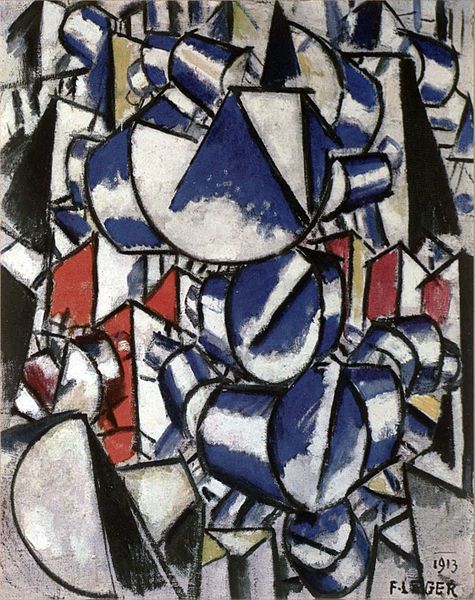

The Section d'Or: The Puteaux Group

Orphism developed within the heady artistic and intellectual milieu of Cubism as practiced by the Section d'Or, an association of avant-garde Cubists who distinguished themselves from Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. The artists of Section d'Or were also known as the Salon Cubists, as they showed in public exhibitions (as opposed to Braque and Picasso who had an exclusive dealer). Many had been Neo-Impressionists and rejected the muted color palette of Braque and Picasso. Robert Delaunay was particularly active in the group and a close friend and collaborator with Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes.

Jacques Villon, older brother of the artists Marcel Duchamp and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, coined the group's name, translated as "the golden section," or "golden mean." This allusion to classicism emphasized Cubism as a continuation of a long-standing Western intellectual tradition, dating back to the ancient Greeks. The group also meant to pay homage to the geometric and mathematical structures of Seurat.

By 1911, the circle was commonly known as the Puteaux Group, as Jacques Villon regularly held meetings at his home in Puteaux. The gatherings brought together the Delaunays, Gleizes, Metzinger, the Duchamp brothers, and Fernand Léger. Frantisek Kupka, who lived in the village, regularly participated as well, the only period of time when the three founding artists of Orphism interacted closely.

The development of Orphism was influenced by the intense discussions of color theory, geometric form, and mathematical harmony and structure that occurred at these salons. As Orphism developed, a number of the group members adopted some of its elements into their artistic practices. The group's major exhibition, the 1912 Salon de la Section d'Or, not only displayed the Cubist works of its members but provided the public forum where Orphism was named as a distinct movement.

Origins of the Term “Orphism”

Guillaume Apollinaire, the influential French art critic and poet, first used the word Orphism at the 1912 Salon de la Section d'Or. There is some debate over the inspiration for Apollinaire's writing on the movement. Some accounts, including Kupka's, said he first used the word to refer to Kupka's Amorpha works as "pure paintings" comparable to music. However, Apollinaire had been living with the Delaunays when Robert Delaunay was writing "La Lumière," and also the text for Apollinaire's "Réalité: peinture pure"; undoubtedly these texts shaped the poet's thinking. In either case, the term referred to the legendary poet, Orpheus, of ancient Greece who had the power to calm wild beasts and all the elements of nature with his song. It brought together the musicality, abstraction, and mysticism of the movement, along with an allusion to classical harmony and natural order.

Apollinaire wrote extensively on Orphism, though he sometimes varied his terminology, as in his 1913 essay, "Quartering Cubism" where he referred to "Orphic Cubism." Still, he made clear that this movement was distinct and more advanced, arguing, "from cubism there emerges a new cubism. The reign of Orpheus is beginning." Indeed, in this essay, he divided Cubism into four categories, although his categorization of painters within the different categories was somewhat arbitrary. Kupka resisted his inclusion in Apollinaire's definition of Orphism, finding it simplistic. He insisted that "in 1911, I created my own uniquely 'abstract' way of painting, Orphism, disregarding all other cultural systems except that of Greece."

Salon des Indépendants, 1913

The Delaunays debuted their Orphist paintings at the Salon des Indépendants in 1913, where they received a great deal of attention, even from America. The New York Times published an article, "Orphism: The Latest Painting Cult," that profiled Kupka and Robert Delaunay, but did suggest the group was a "cult." With its philosophical roots and beliefs in the cosmic symbolism and energies of color, Orphism represented an alternative to the dry cerebral approach of Cubism. This exhibition extended its influence, drawing other painters to adopt the style and identify themselves with the group.

Members of the Orphist circle included the Swiss painter, Alice Bailly, whose 1912 Dans la chapelle (In the Chapel) was influenced by Delaunay's Saint-Séverins series, and the American abstract painter, Patrick Henry Bruce. Alexandr Archipenko and Marc Chagall were both briefly associated with the movement. Indeed, Chagall's closest friends in Paris were Apollinaire and Blaise Cendrars, through whom he met the Delaunays. Feeling a particular kinship with Sonia (they were both born to Russian Jewish families and had studied art in St. Petersburg) Chagall remained close with the couple during the three years he lived in Paris. With its overlapping and contrasting color planes, his 1913 Paris Through the Window shows the influence of Orphist color theory; Chagall also adopted Robert Delaunay's use of the Eiffel Tower as a metaphor for the city.

Apollinaire continued to praise Orphism, singling out the style in his 1913 Les Peintres Cubistes, Méditations Esthétiques as "the art of painting new totalities with elements that the artist does not take from visual reality, but creates entirely by himself." At this triumphant moment, however an argument arose between Apollinaire and Robert Delaunay over the concept of simultaneity, which was also being claimed by the Italian Futurists. Their friendship cooled and they diverged in separate artistic directions before Apollinaire's entry into WWI and his 1918 death. Delaunay would later argue that, by calling it Orphism, Apollinaire "assimilated it into the workings of poetry..." but, because he was a poet, could not "comprehend (its) important structural meaning" in art.

Orphism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Orphism did not develop subtypes or regional interpretations, possibly because it was short-lived due to the outbreak of war. Despite a highly distinctive, radiant style, it also lacked a clear definition of theory and practice, dealing instead with broad and vaguely mystical notions that were not easy to work into a manifesto or any similar system. Even as artists adopted its color theory and use of contrasting colors into their own work in different styles and movements, by 1914, the movement was confined to the practice of the Delaunays and Kupka. Orphism had a second life outside the usual definitions of art, influencing culture at large through the designs of Sonia Delaunay.

Orphism and Literature

The best-known poets to practice Orphism were Apollinaire and Blaise Cendrars, both close friends and artistic collaborators with the Delaunays. Sonia Delaunay had a lifelong enthusiasm for poetry, saying that "painting is a form of poetry, colors are words, their relations rhythms, the completed painting a completed poem." Finding a kindred soul in Cendrars, she collaborated with him on his experimental La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France (Prose of the Transsiberian and of little Jehanne of France) in 1913.

Called a "color poem" by Cendrars, he used varying typography, font size, and colored fonts and juxtaposed time and place to depict his apocryphal journey on the Transsiberian Railway. Sonia Delaunay provided the images, not as illustrations, but as a translation of words into color, or what she called, a "synchromatic presentation." Cendrars wrote that she, "has made such a beautiful book of colors that my poem is more soaked in light than my life."

In 1912, Apollinaire stayed with the Delaunays for several months and was much influenced by Robert Delaunay's color theory and practice. The poet's poem Windows was inspired by and meant to be analogous to the artist's Simultaneous Windows series. Like the different color planes in a painting, the lines in the poem were meant to be read both separately and integrated within the whole in order to create an experience of sensations occurring simultaneously.

Orphism and Design

Sonia Delaunay's interest in design played a key role in the development of Orphism. Her 1911 Couverture de Berceau, a patchwork blanket made for her newborn son directly influenced her husband's 1912 Simultaneous Windows series. As she said, "For me there is no gap between my painting and my so-called 'decorative' work. I never considered the 'minor arts' to be artistically frustrating; on the contrary, it was an extension of my art." Accordingly, her explorations of Orphism extended to designing textiles, fashion, home décor items, and costume for the theater.

Frequenting Le Bal Bullier, a dance hall and gathering place for the artistic and literary avant-garde, she began creating "simultaneous dresses" for herself and her friends. In 1913 she debuted her first such design, which sewed together fabric pieces of varying shapes and sizes in primary and secondary colors. This was meant as an extension of fine art into the real world; as her husband explained, "Dresses were no longer just a piece of material draped in a fashionable way, but seen as an object, a living painting."

Orphism and Popular Culture

Saying, "Our studies in color allowed us to find the life of color in color itself... This is a new science which bears both on poetry and on all modern life," Sonia Delaunay opened her Atelier Simultané in the 1920s in Paris. Here, she designed clothing and accessories in the Orphist style for fashionable society. Her design work supported Robert Delaunay and their family financially, but was also a way in which she advocated for the relevancy of Orphism to the larger cultural realm.

She curated the Boutique Simultané for the Paris Exposition of 1925. This brought celebrity notice, including purchases by the film star Gloria Swanson, the architect Ernö Goldfinger, and the literary figure Nancy Cunard. Her 1926 illustration for the cover of Vogue, where the figure becomes part of the title in a contrasting color design, is just one example of how her work made Orphism part of mainstream culture and design idiom.

Drawing no distinction between high or low art, Sonia Delaunay designed for film and theater, created home furniture and even devised the color schemes for cars: a Citroen B12, painted to coordinate with her fabric designs, in 1925 and, later in 1969, a French Matra M530A commissioned by the company's CEO, Jean-Luc Lagardère. In 1964, she produced a deck of Simultané playing cards in two versions, one with red and blue backs, and the other with green and blue. She had originally designed the cards in 1939, but their production was interrupted by the war. The 1964 edition revisited her original design, updated to include three jokers based on her 1952 Jazz compositions. The deck was so successful that they were produced again in 1980.

Later Developments - After Orphism

As a movement Orphism was relatively short lived; after 1914 only Kupka and the Delaunays continued to paint in the style. Nevertheless, the movement influenced a number of artists and the development of subsequent directions in art. Orphism deeply influenced the development of abstraction, both in its lyrical and geometric styles. Deeply interested in Robert Delaunay's color theory, Wassily Kandinsky invited him to exhibit in the first Der Blaue Reiter show in 1911, where his work was to influence other members of the group, including Franz Marc and August Macke.

Captivated by Orphism's color theory and practice, the Swiss artist, Paul Klee, visited Robert Delaunay's studio in 1912 and translated Delaunay's "Sur la lumière" into German for the magazine Der Sturm. The movement's legacy can be seen in Klee's later use of abstract color shapes.

Among the Section d'Or painters, Orphism resonated with those wishing to expand upon Analytical Cubism. Francis Picabia, Albert Gleizes, Marcel Duchamp, and Fernand Léger all experimented with the style. While living in Paris, American painters Morgan Russell and Stanton Macdonald-Wright developed a movement of abstract art based upon color theory that they called Synchromism, though both later refuted any connection to Orphism.

In postwar painting, Op art used contrasting Orphist colors to create the illusion of depth and movement, as can be seen in the works of Bridget Riley, Richard Anuskiewicz, and Wen-Ying Tsai.

Sonia Delaunay's holistic approach to design, reflected in her clothing, furniture, and objects, became widely adopted by artists interested in creating environments. More recently, in 2015 the fashion designer, Junya Watanabe debuted his "patchwork madness" collection, which paid homage to Sonia Delaunay, using her contrasting designs. In a sense, the principles of Orphism became part of the design vocabulary of modern culture where it continues to represent the hip and the innovative.

Useful Resources on Orphism

- The New Art of Color (The Documents of 20th-century art)By Robert Delaunay, Sonia Delaunay, and Arthur A. Cohen

- Sonia Delaunay, a RetrospectiveBy Sherry A. Buckberrough, Sonia Delaunay, and Robert T. Buck

- Orphism: The Evolution of Non-Figurative Painting in Paris, 1910-1914Our PickBy Virginia Spate

- Apollinaire, Cubism and OrphismBy Adrian Hicken

- Robert and Sonia Delaunay: The Triumph of ColorBy Hajo Duchting, Robert Delaunay, and Sonia Delaunay

- Sonia DelaunayBy Anne Montfort, Guitemie Maldonado, Cecilia Godefroy, et al.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI