Summary of Der Blaue Reiter

One of the two pioneering movements of German Expressionism, Der Blaue Reiter began in Munich as an abstract counterpart to Die Brücke's distorted figurative style. While both confronted feelings of alienation within an increasingly modernizing world, Der Blaue Reiter sought to transcend the mundane by pursuing the spiritual value of art. Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter were the theoretical centers of the group, which included a number of Russian immigrants and native Germans. This internationalism led the group to mount several traveling exhibitions during their brief tenure, making them an indispensable force in the promotion of early avant-garde painting.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

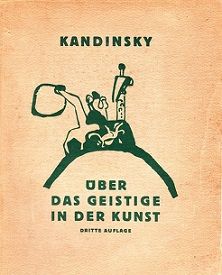

- Though Der Blaue Reiter had no official manifesto, Kandinsky's treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1910) laid out several of its guiding principles. Concerning the Spiritual crystallized the group's pursuit of non-objective or abstract painting and was widely read in avant-garde artistic circles across Europe and beyond.

- Der Blaue Reiter painting was structured around an idea that color and form carried concrete spiritual values. Thus, the move into abstraction resulted partly from radically separating form and color into discrete elements within a painting or applying non-naturalistic color to recognizable objects. The name "Der Blaue Reiter" referred to Kandinsky and Marc's belief that blue was the most spiritual color and that the rider symbolized the ability to move beyond.

- In searching for a language that would express their unique approach to abstract visual form, the artists of Der Blaue Reiter drew parallels between painting and music. Often naming their works Compositions, Improvisations, and Études (among other things), they explored music as the abstract art par excellence, lacking as it does a tangible or figurative manifestation. This also led them to explore notions of synesthesia, the crossing or "union" of the senses in perceiving color, sound, and other stimuli.

- Beside its own groundbreaking artists, Der Blaue Reiter's traveling exhibitions featured the leading proponents of Fauvism, Cubism, and the Russian avant-garde, creating a vital central European forum for the development and proliferation of modern art.

Artworks and Artists of Der Blaue Reiter

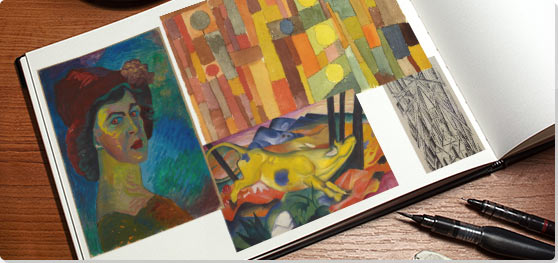

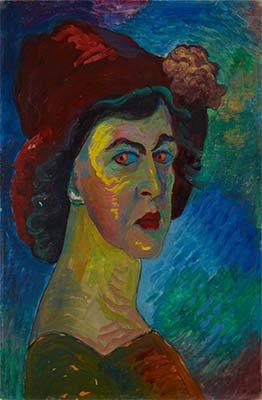

Self-Portrait

A founding member of the Neue Künstvereinigung Munchen (NKvM), Marianne von Werefkin later joined Der Blaue Reiter. Her Self-Portrait of 1910 exemplifies the experimentation of the former group and the semi-abstract manipulation of form and color that would develop in the latter. Her loose, dynamic brushwork shows the early influence of Vincent van Gogh on the NKvM artists and her use of arbitrary color is reminiscent of their study of Paul Gauguin and Edvard Munch. Indeed, the haunting tone she culled from her choice of clashing, vibrant hues, the flattened space of her composition, and the figure's confrontational red-eyed gaze carry all the emotional and symbolic weight of Munch's The Scream, while demonstrating several elements that prefigured the expressionistic painting of Der Blaue Reiter.

Oil on canvas - Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau München, Munich

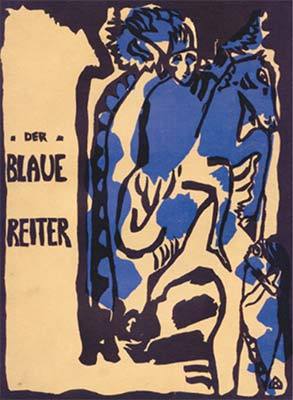

Cover of Der Blaue Reiter Almanach

The name Der Blaue Reiter is widely considered to derive from a 1903 Symbolist canvas by Kandinsky. However, when Kandinsky painted that early canvas, perhaps indebted more to Gustav Klimt or Les Nabis, he had not yet developed the theory of color symbolism he would publish in Concerning the Spiritual in Art. His woodcut cover for Der Blaue Reiter's almanac (published in 1912) is thus more in keeping with the movement's aesthetic and ideals. First, the choice of the bold, flat, "primitive" woodcut format reveals Der Blaue Reiter's focus on direct representation and interest in Primitivism. The choice of the semi-abstract "blue rider," with the color blue symbolizing intense spirituality and the rider symbolizing transcendent mobility, makes Kandinsky's print into a visual manifesto of his key concepts. Beyond his visual offerings, Kandinsky was central to the group as a theorist, and behind this cover he continued that role by publishing two essays and an experimental theater piece.

Color woodcut book cover - Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen, Berlin

The Yellow Cow

Before and during his years in Der Blaue Reiter, Marc developed a color theory that ran parallel and occasionally overlapped with Kandinsky's. In a 1910 letter to August Macke, he wrote: "Blue is the male principle, astringent and spiritual. Yellow is the female principle, gentle, gay, and spiritual. Red is matter, brutal and heavy and always the color to be opposed and overcome by the other two." In Yellow Cow, then, Marc portrayed his emblem of femininity, resounding in its joyous spirituality, barely able to be suppressed or even balanced out by the opposing colors that surround it. Marc was predominantly a painter of animals, and pantheistic "back-to-nature" groups, popular in turn-of-the-century Germany, influenced his idea of spiritualism. Taking a stance closely related to Primitivism, Marc considered animals to be closer to an innate, natural state of spirituality that mankind lost with civilization.

Oil on canvas - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York

Composition VII

Widely considered Kandinsky's prewar masterpiece, Composition VII was, at the least, the mostly highly worked canvas he achieved with Der Blaue Reiter. His largest painting (at 6 by 10 feet), it is a dynamic cacophony of colors and forms with very little in the way of recognizable imagery. Despite the heightened abstraction he achieved, scholars have studied Composition VII in relation to Kandinsky's earlier Compositions and his studies for the painting to uncover apocalyptic motifs borrowed from the Bible's Book of Revelations, such as a walled city on a mountain, the volleys of cannons and fanfares of trumpets, a cleansing flood, and the Last Judgment. Kandinsky's push for abstraction was predicated upon a belief that mankind lived in the end of times and required spiritual rebirth. The widespread destruction of World War I (1914-18) struck many artists and intellectuals as a literal apocalypse, and Kandinsky would later respond by removing all recognizable imagery - especially representations of violent conflict - from his painting.

Oil on canvas - State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The Fate of the Animals

Though Der Blaue Reiter developed its own lineage of Symbolist and Post-Impressionist painters, it belonged to an international avant-garde from which it adopted a range of modern styles. Marc achieved perhaps the most dynamic hard-edged style due to his adoption of Cubist faceting and the force lines of Futurism. Painted with a violence absent from his other major works, The Fate of the Animals has been read as a premonition of the war to come, with a conflagration destroying the animals' forest home. The upright pose of the central blue deer indicates - in keeping with Marc's color theory - the possibility of transcendence. The cross created by the diagonal background suggests sacrifice and rebirth. Many intellectuals, Marc included, saw the forthcoming war as a chance for spiritual renewal. Military service would change Marc's views on this drastically, and he ultimately died in battle. The brown-tinted right third of the painting was restored by Marc's friend Paul Klee after having been damaged in a warehouse fire in 1916.

Oil on canvas - Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland

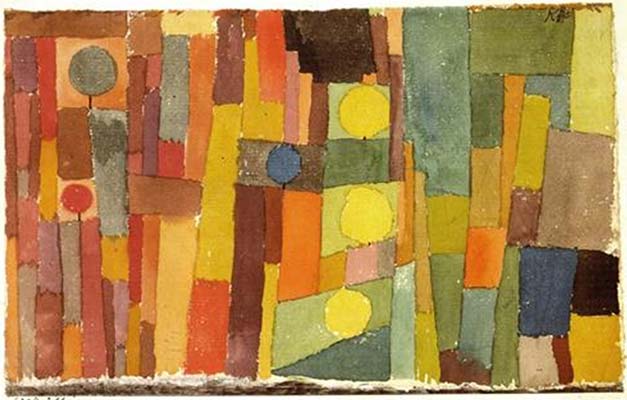

In the Style of Kairouan

Klee's groundbreaking explorations in the field of color theory began with his time in Der Blaue Reiter. Before his affiliation with the group, he was a musician and experimental graphic artist, but he had not developed his talents as a colorist. Inspired by Kandinsky's writings, he began to move beyond his early black and white works toward an intense study of color and abstraction, soon becoming a central member of the group. In 1914 he traveled with Macke and the Swiss painter Louis Moilliet to Tunisia, a trip that revolutionized his growth as an artist. In Tunisia, Klee wrote in his diary of "discovering" color: "Color possesses me. It will always possess me. That is the meaning of this happy hour: color and I are one. I am a painter." Painted after his return to Munich, Germany, In the Style of Kairouan (named after the Tunisian city) is considered Klee's first wholly abstract work. It exchanges recognizable imagery for a balanced geometric composition of circles, rectangles, and irregular polygons delicately colored in a variety of mixed hues.

Watercolor and pencil on paper - Paul Klee Foundation, Kunstmuseen Bern, Switzerland

Farewell

Painted after the outbreak of WWI and the subsequent dissolution of Der Blaue Reiter, Macke's Farewell reflects the darker mood that overtook many European modern artists. His mixed, subdued palette contrasts with the brightly primary colored canvases common to his prewar Blaue Reiter colleagues, and his looming background figures are visually more akin to the alienated men and women in Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's expressionistic street scenes or to Munch's The Scream. These visual cues have been taken to represent his feelings of wartime fear and anxiety. His simplified, featureless figures follow from Der Blaue Reiter's approach to abstraction, though gone is the feeling of spiritual redemption. Sadly, Farewell was the last painting that Macke completed before his death at the front in September 1914.

Oil on cardboard - Museum Ludwig, Cologne

Cathedral, Program of the State Bauhaus in Weimar

Expressionism - specifically that of Der Blaue Reiter - experienced a renewal and afterlife at the Bauhaus. Though the Bauhaus would pursue different goals (and eventually, a more streamlined design aesthetic), Feininger was among several Der Blaue Reiter members who wound up teaching at the groundbreaking institution. His Cathedral woodcut for the cover of the Bauhaus program figuratively marked the institution with a Blaue Reiter "stamp." His choice of a Gothic cathedral - a centuries-old German symbol related to Christian transcendence - is complemented by the modern elements of Cubism, Futurism, Expressionism, and Russian Rayonism that he used to create a vertical, semi-abstract composition. The Bauhaus would use the cathedral as a symbol for their goal of unifying the fine and applied arts under one roof; Feininger cleverly brought this goal into line with the concepts of spirituality and abstraction first put forth in Germany by his Der Blaue Reiter group nearly a decade prior.

Woodcut - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Beginnings of Der Blaue Reiter

The Neue Künstlervereinigung München (NKvM)

In January of 1909, Wassily Kandinsky proposed forming a new group of like-minded artists in opposition to traditional exhibition venues, the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (Munich New Artists' Association), a secession movement that contained several future members of Der Blaue Reiter. The founders included Kandinsky's Russian compatriots Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin, as well as the Germans Gabriele Munter, Alexander Kanoldt, and the German-American Adolf Erbsloh. Aside from their desire to "secede" from the mainstream art institution and their dedication to modern art, these artists shared an expressionistic visual style culled partly from the example of Fauvism and partly from turn-of-the-century Symbolism, as exemplified by artists like Edvard Munch and Gustav Klimt.

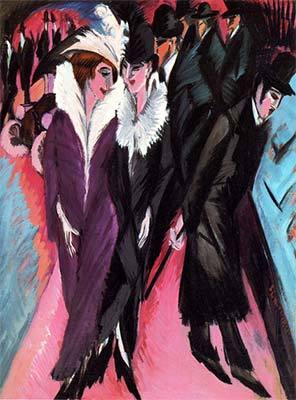

The Two Sides of German Expressionism

The Die Brücke group, operating in Dresden from 1905 to 1911 and in Berlin until 1913, was an early influence for the directness of representation in the work of the NKvM and later, Der Blaue Reiter. The Munich artists, however, pursued rather different goals than their Dresden counterparts. While both groups learned of the importance of bold color from the Fauves, Die Brücke artists used vibrant color to express the heightened emotion of their simplified figures. For Kandinsky and his cohorts those colors needed to go beyond mere emotive persuasion to find resonance in the human soul.

Similarly, while both groups found the Western tradition lacking in inspiration and reached beyond it to "primitive" forms of art, Die Brücke artists would accept a certain level of crude "ugliness" in their art that was typically unwelcome in Der Blaue Reiter's harmonious compositions of color and form. While Der Blaue Reiter was born of the same alienation from the modern world that deeply affected Die Brücke, their answer wasn't to address that feeling through unsettling depictions of traumatic experience, but to attempt to transcend it through abstract artistic means. Die Brücke would, on the other hand, remain averse to total abstraction.

Concerning the Spiritual in Art

In 1910 Kandinsky wrote the treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art, cementing himself as a revolutionary art theorist. An eclectic mix of spiritualism, theosophy, color theory, and art history, Concerning the Spiritual nevertheless managed to make a succinct, impassioned argument for the movement from figurative, naturalistic painting into the realm of abstraction. For Kandinsky, the modern artist had a messianic mission to lead his viewer to spiritual transcendence through his art. The type of art best suited to accomplish this was abstract, or non-objective, art built upon a knowledge of the effect of form and color not only on the eye, but on the soul - a principle he referred to as "inner necessity."

Translated from the original German into French and English and published in 1912, Concerning the Spiritual was widely influential at its time of publication and is still widely considered one of the most groundbreaking theoretical texts in modern art. Kandinsky's suggestion that there were connections between visual components such as form, color, and movement and extra visual elements such as music, emotion, and thought provided the impetus for generations of avant-garde experimentation.

New Members, New Beginnings, and a New Name

The NKvM group mounted three traveling exhibitions during its three-year tenure, through which it accomplished two things. First, it garnered recognition from avant-garde movements outside of Germany, including contributions by Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, and André Derain, among others. Second, it served as something of an incubator for the increasingly radical theoretical proposals of Kandinsky, who would go on to found Der Blaue Reiter. Indeed, by the third NKvM exhibition of 1911-12, the artists of Der Blaue Reiter mounted a parallel exhibition in the opening gallery, having seceded from their own secessionist movement.

In 1911 the artists of the NKvM rejected Kandinsky's Composition V (1911), which he later subtitled Last Judgment. The lack of understanding this represented for his increasingly abstract work - even among his closest colleagues - led him to separate from the group to form the more radical Der Blaue Reiter. Though it kept several key NKvM figures in its orbit (Jawlensky, Werefkin, Munter), Der Blaue Reiter expanded its sights with the addition of Franz Marc, August Macke, Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, and the experimental composer Arnold Schoenberg, as well as the German-American Albert Bloch, the Ukrainian David Burliuk, and the Russian Natalia Goncharova.

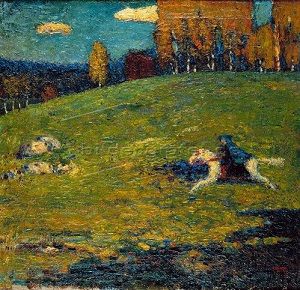

The name for the new group - Der Blaue Reiter - derives from a pivotal 1903 painting by Kandinsky. Painted in an early, Symbolist style, the painting nonetheless marked a turning point for the artist, where he began rendering his forms and colors with less distinct boundaries. By 1911, however, the name had achieved a new meaning due to the writings of Kandinsky and Marc: for both artists, the color blue indicated intense spirituality; for Kandinsky, the rider came to represent - among other things - the journey from worldly figuration to heavenly abstraction.

Der Blaue Reiter Almanach

Due to the centrality of Kandinsky and Marc, Der Blaue Reiter achieved a unifying theoretical rigor that made it a more defined movement than the earlier NKvM. In 1912 the group published its defining statement, the Der Blaue Reiter Almanach, edited by Kandinsky and Marc, which contained a number of theoretical essays by the two artists, one each by Schönberg and Macke, and an experimental theatre piece by Kandinsky. The Almanach also contained over 140 reproductions of works of art, most of which were pieces of "primitive" art, folk art, or children's art. This suggests that the artists of Der Blaue Reiter saw the Western figurative tradition as bankrupt and in need of rejuvenation through outside sources.

Der Blaue Reiter: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

An International Aesthetic

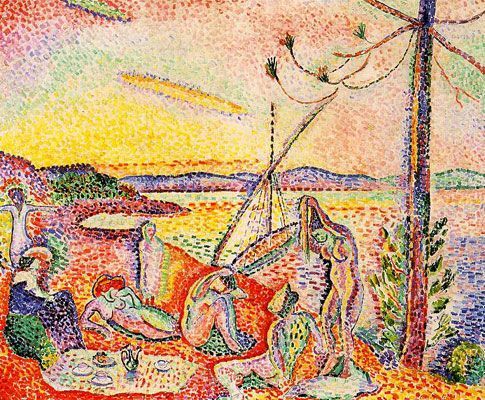

Though style of painting varied from one artist to another within Der Blaue Reiter, certain similarities are worth noting. The expressionistic art of Der Blaue Reiter was envisioned partly as a coloristic rejoinder to the contemporary monochromatic formal explorations being undertaken by the Cubist avant-garde in Paris. If Picasso and Braque were simplifying their palettes to grays and browns to better focus on issues of form, Der Blaue Reiter artists were heightening their use of color and theorizing its symbolic qualities. Indeed, the members of Der Blaue Reiter were well connected to the experiments of Cubism in France, Futurism in Italy and Russia, and a plethora of other splinter movements in Europe. Yet, while all of these aesthetic components of modern art came together in their canvases, they were always inscribed within the artists' intense study of expressive color.

Primitivism and the "Savages" of Germany

In an essay entitled "The 'Savages' of Germany" published in the Almanach, Marc described his colleagues - including the artists of the NKvM, the Berlin Secession, and Die Brücke - as "savages" fighting against an "old established power" to create "symbols that belong on the altars of a future spiritual religion." This rehabilitation of the notion of the "savage" went hand-in-hand with Der Blaue Reiter's interest in Primitivism in the arts.

Primitivism - a perhaps outdated term with negative connotations in the post-colonial era - was nevertheless a positively viewed concept at the beginning of the 20th century. This is because, despite the colonial underpinnings that allowed European artists to know of non-Western cultures, its use in the arts constituted a genuine attempt on the behalf of modern artists to break through the intellectual constraints of modern Western society by reaching to a "simpler," potentially "freer" means of expression in less-developed parts of the world. For the artists of Der Blaue Reiter, this meant that their art often evinced a less laborious, more direct rendering of form far from the obsessive pursuit of naturalism and beauty that had previously been considered the highest goal of art.

Color Theory

In Concerning the Spiritual in Art and in essays published in the Almanach, Kandinsky laid out and developed specific extra-visual values for colors that he defined as Eigenschaften (properties). Yellow, for example, was the color of warmth and excitement; it could signify joy, annoyance, or enervation. Blue was the most peaceful and spiritually resonant color - the darker the blue, the deeper the feeling of calm.

Marc also established a theory of color that assigned symbolic values to specific hues, though his did not necessarily correspond to Kandinsky's. For example, in Marc's woodcuts and paintings - predominantly semi-figural paintings of animals in nature - the color yellow stood for feminine joy, while blue represented masculinity and (like Kandinsky) spirituality. Symbolism in color played out to different degrees in the works of many Der Blaue Reiter artists.

Music and Abstraction

For Der Blaue Reiter, music was the perfect analogy for the abstract visual arts. Not only was music capable of evoking deep emotional responses or spiritual resonances, but the timbres of certain instruments might evoke certain images or associations despite the inability for the human eye to "see" music. In addition, the language of sound and music lent a vibrancy and descriptive power to abstract art: painted compositions could be loud and cacophonous or quiet and harmonious; a pigmented form could crescendo across a canvas, or a pairing of hues could create a visual vibrato.

In addition, several of the members of Der Blaue Reiter had direct relationships to music. Besides being an exemplary painter, Schönberg is among the most important experimental composers and theorists of 20th-century music, and his students included the groundbreaking artist-composer John Cage. A musician from his teenage years, Klee played violin in an orchestra well into his maturity as a painter. The poet Rainer Maria Rilke once wrote of Klee, "Even if you didn't tell me he plays the violin, I would have guessed on many occasions that his drawings were transcriptions of music." The contents of the Der Blaue Reiter Almanach demonstrate the group's commitment to musical form: a reproduction of one of Schönberg's songs, two others by his colleagues Alban Berg and Anton Webern, and an essay on "Anarchy in Music" by the Russian composer Thomas Alexandrovich de Hartmann.

For Kandinsky, the synesthetic relationship between color and sound could even be codified. In what he described as Klangfarbe (sound tones), each color had a pitch and volume, so to speak. Yellow, whose Eigenschaft was excitement, was connected to loud, sharp sounds. Blue, the color of peace and spirituality, was richer, and deep blues had a more sustained sound tone. Moreover, Kandinsky suggested that hues of varying saturation corresponded to the timbres of specific instruments, where red was the strong, forceful playing of a trumpet fanfare or a high, clear violin, and green was a gentle violin played at middle position. Fittingly, Kandinsky contributed an experimental theatre piece entitled The Yellow Sound to the Almanach as the first in a four-piece group of "color-tone dramas" he wrote, including The Green Sound, Black and White, and Violet.

Later Developments - After Der Blaue Reiter

The end of Der Blaue Reiter was almost entirely due to the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Due to their Russian citizenship, Kandinsky, Jawlensky, and Werefkin were deported, with Kandinsky returning to Russia and Jawlensky and Werefkin immigrating to neutral Switzerland. Macke died in action a mere two months into the war, and Marc died at the Battle of Verdun in 1916.

The group was, however, extremely influential on generations of artists to come. Before their dissolution, the participation of Der Blaue Reiter in the groundbreaking 1912 Sonderbund exhibition in Cologne placed them among many of their artistic predecessors, including Munch, Klimt, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin. One year later, when the curators lent a large number of canvases to the Armory Show in New York City, Kandinsky's art was seen for the first time on American soil.

Kazimir Malevich's creation of Suprematism in Russia in the mid-1910s is unthinkable without Der Blaue Reiter's theory of abstraction and spirituality as a model. The subsequent development of geometric abstraction in the Dutch De Stijl movement, best exemplified in the art of Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg, owes a debt to both Kandinsky and Malevich.

Indeed, De Stijl and Der Blaue Reiter would come together under the roof of the Bauhaus, which might be seen as a next chapter for Der Blaue Reiter. Though the Bauhaus is predominantly (and accurately) thought of as a school of design, many of its early faculty were Expressionist painters. Among the initial appointees were Feininger and the Swiss Expressionist Johannes Itten, whose spiritual approach to abstraction paralleled Der Blaue Reiter's. Klee joined in 1920 and Kandinsky in 1922, forming a nucleus of painters that carried Der Blaue Reiter's experimental abstraction and color theory into the Bauhaus curriculum - a curriculum still imitated widely in art schools today. In 1924 while Kandinsky, Feininger, and Klee were together in Weimar, the painter and art dealer Emmy Scheyer brought Jawlensky back into their midst to form the exhibition group Der Blaue Vier (the Blue Four), promoting their art as an ensemble for the next decade.

Through the influence of Scheyer's exhibitions, the popularity of Klee and Kandinsky's art, and the immigration of the Bauhaus-taught painter and educator Josef Albers to the United States in 1933, the artists of Der Blaue Reiter also left a strong imprint on the development on Abstract Expressionism - perhaps most notably in the work of Jackson Pollock, Arshile Gorky, and Mark Rothko. Pollock and Gorky's mature gestural styles and Rothko's focus on color combinations and the emotions carried or evoked by certain hues owe directly to the example of Kandinsky's painting.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI