Summary of Rayonism

Considered the pinnacle of avant-garde art by the founders Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, Rayonism (sometimes translated from Russian as Rayism) developed new ways to express energy and movement. From its conception as a subset of Russian Futurism, Rayonism drew from scientific discoveries and the theoretical conceptions of the fourth dimension. The movement was very self-consciously modern, even as it incorporated elements of traditional folk culture. It was also fiercely nationalistic, projecting itself as a distinctly Russian style, despite its obvious inspiration from European movements including Cubism, Orphism, German Expressionism, and Futurism.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Influenced by both close connections to an international avant-garde and native traditions of Russian art and craft, Rayonism captures the contradictions of Russian culture in the pre-Revolutionary era. It was presented as an unapologetic combination of cosmopolitan and nationalistic impulses, sometimes referred to as Everythingism. This encyclopedic approach to style and subject was considered the essence of the modern pace of life.

- The style and subjects of Rayonism reflected contemporary scientific and metaphysical developments. The adoption of transparency and fractured objects was influenced by changing understandings of the material world through the discovery of x-rays and radioactivity. The world no longer could be thought of as purely solid and concrete. This, in turn, reinforced fourth-dimensional theories of space and experience as a continuum of our observable universe. By focusing on light as subject matter, the artists could dissolve objects into their surrounding space; these layers of transparency were thought to be representative of the fourth dimension.

- The Rayonist interest in popular culture and materiality (known as faktura) broke with the expectations of fine art. Believing that their work spoke to larger questions of existence and spirituality, the Rayonists aspired to break down the boundaries between art and life. This would be mirrored in the work of the later Suprematist and Constructivist artists, who embraced faktura as a means of constructing spiritually-charged spaces in the post-Revolutionary years.

Artworks and Artists of Rayonism

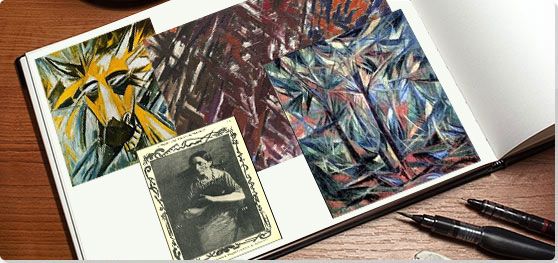

Peacock in Bright Sunlight (Egyptian Style)

This painting is one of a series on peacocks, where Goncharova combines elements of the primitive styles of Egyptian and Russian folk art with Rayonist abstraction. The result reflects the juxtapositions and contradictions common to the style, as she freely mixed ancient and modern influences. Showing the peacock's head and neck in profile, she borrows the composite pose (common in Egyptian art), which allowed for the greatest amount of information to be described in simple contours. Likewise, the tail is spread out in a frontal view, to highlight the defining characteristic of the subject. The blocks of brilliant color suggest Russian folk painting and decorative arts. Their non-descriptive, unrealistic hues transform the recognizable shape of the peacock's plumage into an abstract array of color.

Following principles of Realistic Rayonism, the peacock is clearly delineated and yet remains simply the point of departure for the more eye-catching green oval of the body and the intensely colored, semi-abstract tail. That tail creates a sense of independent movement as the colors contrast and create visual tension, yet the composition of the feathers can also be read as a classical architectural arcade or a painter's palette. These allusions are not contradictory, but allowed to co-exist and ultimately create a more dynamic field of possible interpretations.

Oil on canvas - The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Old-Fashioned Love

The literary concept of Zaum poetry, comprised of nonsensical sounds that assaulted traditional language structures, was embraced by the Russian avant-garde as a means of breaking with the past. Like the Italian Futurists, who were contemporaneously adopting similar approaches in their poetry, the intent was to create a wholly modern, sensorial alternative. Alliances with sympathetic visual artists, such as this collaboration between Kruchenykh, a radical Russian Futuristic poet, and Larionov, were common.

Like the Rayonists, Zaum poets wanted to break into new forms of expression; Kruchenvkh first began publishing postcards before embarking on lithographed books and collaborating with other poets and artists. Old-Fashioned Love was the first of his collaborations with Larionov; Larionov and Goncharova would eventually partner with him on eight books, including Igra v adu (A Game in Hell) in 1912, Worldbackwords and Pomada (Lipstick) in 1913.

This front page shows Larionov's Rayonist depiction of a vase of flowers, with the contours exaggerated in thick, forceful black lines. Limited by the lithographic medium, this print was nonetheless an important step in the development of the "rays" of light as Larionov balanced his representation of an object with his disintegration of that object into light. The work remains Realist Rayonism; indeed, his images in the book drew from natural subjects - flowers, leaves, vines - and human figures illustrated in the Neo-primitivist style of Russian lubki. These lubki were inexpensive woodblock prints that decorated many Russian homes; they provided a common source of native folk iconography for the avant-garde, who valued both their naïveté and their nostalgic familiarity. That he alternates between the forward-looking Rayonist style and retrogressive primitivism reflects the open and all-encompassing stance of the movement. Similarly, Larionov staged the Target show at the same time that he was organizing the exhibition "Original Icon Paintings and Lubki," which focused on highly native and traditional forms of image-making.

Book with lithographs and lithographed text on cream wove paper - The Art Institute of Chicago

Cockerel and Hen

In this work of Realistic Rayonism, the artist depicts a dynamic rooster in rays of red and gold; a hen, barely identifiable, appears in golden planes of color beside it. While the objects of the painting are discernable, the true subject, however, is their merging with the background space and their disillusion into rays of light and vectors of energy. This is particularly evident in the left half of the painting, as the lines of reflected light intersect in a chaos of dynamic force lines.

From the early development of the movement, Larionov emphasized the symbolic and visual power of light and radiance, an interest that belies the influence of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. In his modernization of those 19th-century studies of light, however, he explained, "it is not the objects themselves that we see, but the beams of rays that emanate from them, which are shown in the picture with color lines." The light rays come from the objects and the surroundings, and as a result the subject and its surroundings are integrated into their surrounding environments. Like Cubism, the distinction between the object and its space is complicated, however the Rayonists were motivated by their metaphysical interests in the fourth dimension and their search for a unified expression of energy that surpassed the concrete object.

Oil on canvas - The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Glass

It is possible, but quite difficult to locate the two bottles, five tumblers, and goblet on a table in this painting, as the objects have been rendered in layers of transparency and broken up by intersecting rays of light. In this transitional work, between Realistic Rayonism and Pneumo-Rayonism, remnants of the objective world are simply points of departure for the light rays. Even the title veers toward abstraction, as it refers to glass as a substance, rather than as the objects made from it; while focusing the viewer on the materiality of the objects and the transparencies of their depiction. One well-informed review of 1913 wrote that the painting depicted, "simply 'glass' as a universal condition of glass with all its manifestations and properties."

Larionov considered Glass to be his first fully Rayonist painting. It is, indeed, one of the first in this style to be publicly exhibited, appearing at the 1912 World of Art show that predated any published explanation of Rayonism. The precise date of the work is murky; for a 1914 exhibition in Paris, the artist dated the work to 1909, but this date is certainly untrue. It was an attempt to claim precedence over other abstract styles.

Oil on canvas - Guggenheim Museum, New York

Rayonist Composition: Domination of Red

In this work of Pneumo-rayonism, any reference to the external world has vanished in intersecting dynamic light rays and colored planes. The space becomes tangible, a palpable shape. Indeed, an energetic but indefinable form, full of depth, layers, and movement seems to inhabit the canvas. Space and energy are the subject of the painting.

And yet a clear message is conveyed. The title's use of the word "domination" indicates the conflict between the colors, their fight for primacy. By this stage, Rayonism had quickly evolved from merely describing light rays to what Larionov called, a "painting of space revealed ...by the ceaseless and intense drama of the rays that constitute the unity of all things." In this larger evocation, he felt that colors produced different reactions, and that, by manipulating their density, he could create a construction of sensations and effects. Thus, the color lines and planes are meant to provoke intuitive feelings and as the red dominates this space, it becomes the means of communicating with the viewer.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Nature Morte aux Fruits

Demonstrating the stylistic fluidity of Everythingism, this painting features the Cubo-Futurist depiction of Neo-primitivist objects; only the transparency of the still life explicitly marks the painting as Rayonist. A table overflowing with fruit - pears, apricots, plums, grapes, oranges, lemons, and watermelon - appears along with plates, a crystal bowl, and, at the top right, a white napkin with a traditional lubki image of a man riding a blue horse. Everything is rendered transparent; the pits can be seen inside the apricots, and, through the translucent watermelon, the plate on which it rests is visible as is the detail of its floral pattern. This intermingling of layers unifies the objects, even as they are dissected by this x-ray vision.

Goncharova unites a number of disparate elements in the work: some of the fruit like the oranges and lemons would have been exotic, whereas plums and apricots were not; the dishware is both hand-painted Russian porcelain and expensive glass. The startling modernity of the depiction is interrupted by the highly traditional folklore element of the horse and rider (a motif also adopted by the Russian-born Expressionist Wassily Kandinsky). Similarly, the tablecloth in the lower right resembles embroidered Russian linen and evokes a simpler, domestic past. While the style is modern, the subject is not. We are presented with an abundant, colorful feast that is recognizably Russian and familiar.

The painting follows contemporary theories on transparency as an expression of objects unified by scientific vision that could see beyond concrete surfaces. Indeed, the three-dimensional world is no longer a solid reality in and of itself, but subject to the artist's x-ray vision, making seen what was impossible to the ordinary eye. The painting was likely included in Goncharova's 1913 solo show, where it would have been one of four paintings to feature transparencies. The work also appeared at her 1914 show with the title, Still Life (Principle of Transparency). The composition also incorporates a collage aesthetic, layering objects without blending them in a unified pictorial space or scale. This collage quality had been celebrated by the French poet Apollinaire as emblematic of the modern experience. This link is made clear, as Goncharova gave the painting to Apollinaire; an inscription on the back reads, "As a souvenir to Mr. Apollinaire from his admirer, Natalia Goncharova June 1914 Paris."

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Rayist Composition

There is an almost postmodern element of self-referentiality and metarepresentation in this painting, which plays with the notions of figuration and abstraction (Realistic and Pneumo-Rayonism) by depicting an abstract painting as the subject of the canvas. Set in the center of the work is a discrete second painting, a Rayonist composition of superimposed Russian words, light rays and planes of color that form long extended triangles, pointing downward.

Shevchenko's hybrid of Realistic Rayonism and Pneumo-Rayonism creates a complicated paradox. The viewer must both study the represented scene and the abstraction of that secondary image. Furthermore, the light rays and forms that extend beyond the smaller image confound the boundaries of these two spaces. The Realistic element depicts the abstract play of colors, shapes, and textures on a canvas. As might be expected from such a self-referential work, there's also a hint of wit; the light rays are reflected from the smaller painting, suggesting that art itself lights up and colors the surrounding space.

Gouache on paper, laid down on board - Private Collection

Rayonism: Blue-Green Forest

In this painting, the Rayonist rays of blue, green, black, and white work on a representational and abstract level: they suggest the dense, dark foliage of the titular forest, while also evoking an energetic and overwhelming sense of life and movement. Goncharova painted multiple Rayonist works focused on this subject, perhaps drawing upon Ouspensky's belief that the forest, animistic and unified, exemplified what he called the "life-activity" of the fourth dimension. It was a space that was comprised of infinite individual units, bound together into one living biome. Goncharova takes this notion and adds to it the splintering vectors of Pneumo-rayonism, although there remains a suggestion of a woman's face on the left, and, at the bottom of the canvas, a large dragonfly.

The work was shown in Goncharova's 1913 solo exhibition; her artist statement for the show underscored this connection to mysticism and spiritual energies. Her contemporaries understood this cosmic scale as representative of fourth-dimensional theories that attempted to depict higher levels of consciousness. The art critic Anthony Parton, wrote "The painting is a bold attempt to recreate...the whole world in its spiritual and concrete totality." In any case, a sense of the forest as a dynamic and unified force fills the canvas; even the woman and the dragonfly exist as hints of perception, perhaps nothing more than imagined shapes in dense foliage.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Sunny Day (Pneumo-Rayist Structure Based on Color: Composition)

A prime example of Pneumo-rayonist abstraction, this non-objective painting also points toward the legacy of Rayonism in post-WWI, post-Revolutionary Russia. Larionov has created a formal composition of nothing more concrete than intersecting light rays, textured planes, and fragments of text. The work communicates to the viewer solely through the emotions evoked through color and line, as suggested by the equally abstract title.

At the same time, there remain suggestions of symbolism in the included lettering. Possibly the letters "KA," which appear in red at the center of the painting might be references to contemporary colleagues: either the Russian Futurist writer Vasily Kamensky (who developed ferroconcrete poems), or to Velimir Khlekbnikov's famous prose work, Ka, which was later referenced by Malevich in his painting Aviator (c. 1914). Given Larionov's interest (along with Goncharova) in ancient Egyptian art, it is also possible that this refers to the notion of a spiritual essence, known as the Ka, which was central to their conception of the afterlife. All three possibilities would amplify the pictorial energy created by color and line. The artist felt this work to be so significant that he gave the painting to Apollinaire following its 1914 exhibition in Paris.

The reference to structure in the title of this work reflects Larionov's innovative use of faktura as an element of the painting. Breaking from the flat surface of the canvas, he used paper maché, plaster dust, and glue to create a three-dimensional surface; this materiality also offered new possibilities for texturing, which in turn allowed for greater expressionism in the application of paint. Faktura, literally meaning "surface," emphasized the artist's unconventional choices in comparison to the classical importance of oil painting. From 1913-1914, Larionov often gave his non-representational work titles like "structural construction," or "colorful structure," as he increasingly composed his work according to texture and color, the intrinsic qualities of painting. This abstract understanding of purely formal terms, while maintaining a spiritual quality to painting would be key to Malevich's Suprematism and the work of Constructivists in post-Revolutionary Russia.

Oil on canvas - Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

Beginnings of Rayonism

The brainchild of life-long partners Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, Rayonism synthesized elements of Russian avant-garde painting to create a deliberately modern style. As Russian Futurists associated with the Knave of Diamonds (also known as the Jack of Diamonds) group, they had experimented with Neo-primitivism, which recovered traditional motifs in a style that tried to replicate the naïveté of folk art, along with Russian Cubo-Futurism, which blended Cubist distortion with depictions of movement. In 1912, when Larionov and Goncharova broke with the Knave of Diamonds group to stage The Donkey's Tail exhibition, they rejected the notion of stylistic unity and included a broad range of work. This pluralism would remain part of Rayonism, even as the artists began to define general themes of the style. In part, scientific writings on the discovery of radioactive rays and x-rays were instrumental to their depictions of dynamic time and space (Larionov had most likely read Marie Curie's Radioactivity and The Discovery of Radium, both recently published in Russia).

The Fourth Dimension

Through their friendship with the artist Mikhail Matiushin, the couple also encountered the work of Peter D. Ouspensky, a Russian mathematician and esoteric philosopher whose fourth-dimensional theories influenced all iterations of the Rayonist style. Notions of the fourth dimension were popular in the early-20th century, but were often rather unscientific. Expounded in his The Fourth Dimension (1909) and Tertium Organum (1912), Ouspensky's theory of the fourth dimension influenced other artists as well, including Guillaume Apollinaire, Max Weber, Umberto Boccioni, Marcel Duchamp, and Kazimir Malevich. His fourth dimension was a realm of cosmic consciousness, accessible to artists and mystics able to see in flashes of understanding that which could not ordinarily be seen. Drawing upon Hindu ideas, Ouspensky defined the fourth dimension as a unified state, where a human being was integrated with the environment; this element particularly appealed to Goncharova, who had an ongoing interest in Hinduism. The idea that true reality was not visible to the eye seemed to be confirmed by the scientific discoveries of radioactivity and x-rays, which also provided a formal inspiration for the visual elements of the style.

Esoteric and spiritual, Ouspensky called for artists to become "Supermen" who would lead the way into a new consciousness. This characterization was not uncommon among avant-garde artists of the time, including Kandinsky and Malevich, who also believed themselves charged with guiding people to higher levels of thought. For the Rayonists, this manifested in their use of the term budushchniki, roughly translated as "future people" to describe themselves. To illustrate their new painting style and positioning themselves as the movement's creators, Larionov's Rayonist Portrait of Goncharova and Goncharova's 1912 Portrait of Larionov were included in their July 1913 manifesto.

Exhibitions of Rayonism

The exact beginning of Rayonism is difficult to pinpoint, especially since Larionov occasionally backdated his work to make it seem more prescient. The first confirmed appearances of Rayonist work were in 1912, published in the book, Old-Fashioned Love (which included Futuristic poetry by Alexei Kruchenykh with Rayonist images by Larionov). Larionov's Glass (Method of Rayonism) and Rayonist Study were also exhibited that year at a World of Art exhibit, and Rayonist Mackerel and Sausages at the Union of Youth show. In June 1912, the first definition and description of the movement were published in a manifesto brochure, "Rayonism." Although it was certainly influenced by German Expressionism, Italian Futurism, and French Orphism, the press cast the style in a nationalistic tone with Pavel Ivanov describing it as "entirely Russian with a completely new technical method." The couple introduced the movement to their friends, Maurice Fabri, Mikhail Le Dantiu, Vladimir Obolensky, Sergei Romanovich, and others who were part of The Donkey's Tail, a group that rejected European influence in favor of art rooted in their motherland. That fact that they named the show after an infamous 1910 hoax in Paris, when a canvas painted by attaching a brush to the tail of a donkey was exhibited as modern art, reveals the complexities of their relationship with the West.

The First Exhibition: Target

Rayonist painting officially debuted in the 1913 Target exhibition, organized by Goncharova and Larionov as a deliberate provocation after the outraged response to The Donkey's Tail. To publicize the show, they held a public debate on avant-garde art and theatre at the Polytechnical Museum. The evening attracted a great deal of media, mostly due to the ensuing chaos, described in the local newspaper: "Mr. Larionov, the presiding chairman, prevented one of the critics from speaking. The audience protested, surrounding the stage. Running up, Larionov threw an electric light bulb into the audience, then the water decanter. Someone from the presidium hurled a chair into the audience and made off. A student shouted that he had caught the man who threw the chair into the crowd and boxed his ears. A genuine fight began. The police were called into the hall and the meeting was closed." The intent was to create a sensation and to break with the staid traditions of art; the event was a mixed success. Indeed, as a result of the confusion, the Russian press mistakenly identified Larionov and Goncharova as associated with Italian Futurism, whose members often deliberately antagonized their public with similar stunts.

The Target exhibition also sought to change the standards in showing works by painters not affiliated with any group or style and de-emphasizing personality by focusing less on the individual artists. The result was very eclectic, including Russian Futurist and Neo-primitivist work by former members of The Donkey's Tail, work from the group of professional, commercial sign painters, children's art, and paintings by amateurs.

This wide-range of styles reflects the synthetic nature of Rayonism, which positioned itself as the culmination of modern art. (This strategy would be repeated in 1915 with Kazimir Malevich's announcement of Suprematism.) Indeed, the show's statement celebrated "all the styles that existed before us and which have been created today such as Cubism, Futurism, Orphism. We declare that all combinations and mixtures of styles are of value." Within this mix of modernist movements, they staked a claim as being the most advanced, declaring "We have created our own style, Rayonism, whose objectives are spatial forms and making painting independent, governed only by its own laws." At a time when few movements were explicitly pursuing abstraction as an end goal, the Rayonists made non-objectivity a central aim of the style. This announcement of Rayonism was overshadowed, however, by the media attention given to the opening event and the eclecticism of the work shown. The movement itself attracted few artistic practitioners; Goncharova and Larionov would be the most dedicated and most widely recognized.

Rayonist Manifesto

A more deliberate pronouncement was made in July 1913, when "Rayonists and Futurists: A Manifesto," authored by Goncharova and Larionov, was published. The manifesto was co-signed by a number of avant-garde artists, most of whom had participated in the Target exhibition, including Ivan Larionov (the artist's brother), Timofei Bogomazov, Kirill Zdanevich, Mikhail Le-Dantiu, Vyacheslav Leskievsky, Sergei Romanovitch, Serge Oblensky, Morits Fabri, and Alexander Shevchenko. The manifesto's declarations repeated the points of the Target brochure, but more carefully established Rayonism as a new style that was definitively Russian. They advocated a national art, identifying Russia with the East, while, at the same time, celebrating, "the whole brilliant style of modern times." Possibly to dismiss any comparisons with European avant-garde styles, the manifesto also rejected "individuality as having no meaning for the examination of a work of art" and asserted "that there has never been such a thing as a copy...(as) art cannot be examined from the point of view of time."

The movement's central form, "The ray... depicted provisionally on the surface by a colored line," was described as "spatial forms arising from the intersection of the reflected rays of various objects, forms chosen by the artist's will." Similar to the force lines of Futurism, these vectors both described and dissected the objects depicted, creating a sense of movement that guided the viewer through the composition. This dynamism was considered a visual representation of the fourth dimension, which had both a temporal character and a metaphysical quality of higher consciousness. Seeking to evoke sensations, the manifesto explained that the "length, breadth, and density of the layer of paint are the only signs of the outside world - all the sensations that arise from the picture are of a different order; in this way painting becomes equal to music while remaining itself."

Rayonism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

The distinctive splintering effect of Rayonism began as a way to extend objects into their surrounding space. This was thought to represent fourth-dimensional unity and the energies between all things. In works such as Bull's Head (1913), Larionov features a simple subject (often one from Neo-primitivism, such as this common farm animal), but explodes the contours of the bull to create a dynamic and active field of energy. The bull is no longer a discrete object, but part of a larger, pulsating cosmos. This example of Realistic Rayonism would soon give way to works that created those sensations through color and line, leaving behind subject matter to focus on purely formal qualities. Although the Rayonists were predominantly painters, they did experiment with other formats for their work, including publishing and performance.

Realistic Rayonism

The earliest Rayonist paintings were in the Realistic style, explained in the Target exhibition leaflet as "depicting existing forms." Yet, already the artists aspired to more abstract and metaphysical goals that would achieve "the erasure of the border between what is called a picture plane and nature." In this vein, first-generation Rayonist paintings, most often by Goncharova and Larionov, worked from an existing form, usually an identifiable natural subject, as a point of departure. That object was then distorted by the fracturing of its shape by radiating light rays that created geometric facets and divided planes.

Realistic Rayonism drew upon Ouspensky's explanation of mathematical theories on the fourth dimension and how forms could be created by extending the contour lines of a three-dimensional object. This provided a strategy for abstracting from the original object, and in time Rayonist artists would abandon that link to the concrete universe in favor of pure depictions of light and energy. In a relatively brief period of time, the subject of the painting was displaced by an emphasis on the rays, as can be seen in Larionov's Cockerel and Hen (1911), where only one wing and the head of the cockerel are recognizable. This abstraction led to the development of Pneumo-Rayonism.

Pneumo-Rayonism

In July 1913 Larionov published a manifesto that declared "Pneumo-rayism or concentrated Rayonism" as the "next stage" in modern art. Also known as Unrepresentational Rayonism, this period rejected the representation of objects from the concrete world. All that remained of the painting's inspiration or subject was a reference in the title; the paintings themselves depicted only intersecting light rays and dynamic color planes. Works such as Sea, Beach, and Woman: Pneumo-Rayism (1913) teeter between abstraction and non-objective art as Larionov dissected and decomposed the subject beyond recognition. By the time of his Rayist Composition (1913), the subject was entirely removed and the surrounding environment was consumed by abstract lines and planes of color. Larionov believed that these paintings of line and texture created "the sensation of the fourth dimension."

Theories of the fourth-dimension provided philosophical and pictorial guidance. A number of Goncharova's Pneumo-Rayonistic works were inspired by the forest, which Ouspensky believed to exemplify the "life-activity" of the fourth dimension. Similarly, the rays depicted were thought to project a sense of energy and movement while alluding to the original subject. Depicting light allowed the artist to represent layers of reality and transparency, thought to be one method of visualizing the fourth dimension. Conceptualizing the fourth dimension as a comprehensive expression of life and a higher plane of consciousness, the term "pneumo" may allude to "pneumatism," an ancient Greek idea, in which the breath of the pneuma is associated with all life.

Rayonist Performance

Breaking down the boundaries between art and life was a common concern among the Russian avant-garde. From the beginning, performance was an integral aspect of Rayonism, reflected not only in the provocative events surrounding their exhibitions, but in their creation of artistic cabarets. In 1913 Goncharova and Larionov opened a cabaret called The Pink Lantern, followed by The Tavern of the 13, both in Moscow. In these short-lived performance spaces, they featured face-painting, tango dancing, confrontations with the audience, and artistic disputes. Larionov's essay, "Why we paint ourselves: A Futurist Manifesto" explained that "It is time for art to invade life."

Film and photography were enlisted in these efforts. The Tavern of the 13 was made into a 1914 film, Drama in the Futurists' Cabaret No. 13, starring Goncharova and Larionov who were both depicted wearing facial Rayonist tattoos. This disfigurement was intended to mark the transgressive nature of their art and to transform themselves into futuristic living canvases. It also drew upon the tradition of Russian carnivals that included minstrels, clowns, puppet shows, and other popular entertainments, providing another attack on the traditions of art by erasing the distinction between 'high' art and 'low' art.

Everythingism

At the same time that Goncharova and Larionov were promoting Rayonism, they also maintained a multiple approach to style, which they referred to as "Everythingism." Thus, they and their colleagues mixed elements of old and new, high and low, Neo-primitive and modern. In her 1913 "Creative Creed," Goncharova proclaimed it her right to simultaneously disregard "symbolism, decadence, futurism, all of which I have experienced," and incorporate these styles into her work. Her statement shows a profound connection to Ouspensky's claim that "moments of different epochs, divided by neat intervals of time, exist simultaneously, and may touch one another"; both reflect the sentiment that the quickened pace of modern life had created new sensations of time and experience, making obsolete the old differentiations of styles and ideologies.

The artist Ilia Zdanevich and Larionov promoted this eclectic artistic practice, particularly in exhibitions that mingled styles freely. The first "Everythingist" event took place in December 1913; here, a painting such as Goncharova's Rayonist Garden (1912-1913) exemplifies the multiplicity of the style, synthesizing a Cubist treatment of foliage, Futurist use of text, and Neo-primitivist color with a Rayonist treatment. As the artist Benedikt Livshits explained, "Essentially, 'everythingness' was extremely simple: all ages and movements in art were declared equal. Each of them served as a source of inspiration for the everythingists who had conquered time and space."

Later Developments - After Rayonism

Though Goncharova returned to the style as late as 1956 (in her painting Rayonism of that year), the movement ended in 1914 with the departure of the couple for Paris. Here, their styles changed radically as they began designing for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballet Russes productions. Their later work in the post-Revolutionary period would replace the splintering effects of Rayonism with more concrete geometric abstraction.

However, the movement had a long lasting and profound influence on the development of Constructivism and Suprematism, particularly affecting the revolutionary artists Lyubov Popova and Alexander Rodchenko. By building from national folk styles and Neo-primitivist painting to increasing levels of abstraction, Rayonism made possible the characterization of non-objective painting as a Russian style. Because it integrated elements of western European painting, such as Expressionism, Cubism, and Futurism, into a local style, it provided a national source for modernism that also helped to position abstract painting as the first style of the 1917 Revolutionary government.

The Rayonist idea that equated painted rays with the immateriality of light provided new possibilities for the materiality of painting and encouraged artists to think about the form and structure of their paintings as meaningful. When Malevich wrote "Any picture consists of a colored surface and texture... and of the sensation that arises from these two," his emphasis on form reflects Rayonist abstraction. Similarly drawing upon Rayonist ideas, the Constructivist Popova embraced "the line as color," arguing that the line "directs the forces of construction." She, along with many of the Constructivists and Suprematists, was also influenced by Larionov's faktura, a term that refers to the surface or texture of the painting. Faktura would become a critical component of post-Revolutionary Russian art, particularly in the monochromatic panels of Malevich and Rodchenko and the sculptural constructions of Vladimir Tatlin. Indeed, Tatlin paid homage to his roots in Rayonism, avowing "We all came out of Larionov."

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI