Summary of Olga Rozanova

Olga Rozanova was a member of many of the most important art groupings and movements in early-20th century Russia, while the development of her work across the 1910s represents in microcosm the evolution of the Russian avant-garde over the same period. In this sense, she is significant as an exemplary artist of her era, but in many ways, Rozanova was also an exceptional figure: not just as one of few women attached to movements such as Cubo-Futurism and Suprematism, but in bringing her individual theories of spiritual energy and color interaction to bear on those movements, resulting in a unique and emotionally dynamic body of work. Had she not died of diphtheria in 1918 at the age of just 32, she might well be placed alongside Kazimir Malevich as one of the pioneers of 20th-century abstract painting.

Accomplishments

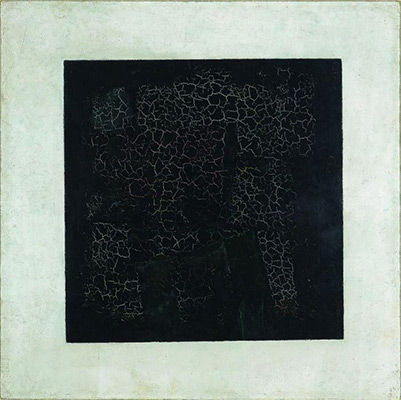

- Rozanova was at the center of the artistic debates and experiments in Russia leading to the conception of Suprematism in 1915. This movement is now associated with Kazimir Malevich's iconic reduction of the picture plane in works such as Black Square, but Rozanova's abstract collages and paintings were equally vital exemplars of the pure abstraction which defined the style. Indeed, she spoke of such work as an unacknowledged precursor for Malevich's characterization of Suprematism.

- Rozanova's Cubo-Futurist and Suprematist paintings were set apart from those of her peers, including Malevich and El Lissitzky, by her emphasis on the interplay and vibrancy of color, visual exercises in exploring the emotional and conceptual effect of interacting tonal groups. She linked these experiments to her attempts to express an inner spiritual energy through her work, and the resultant body of paintings and collages makes a unique contribution to movements otherwise defined by more purely geometrical forms of abstraction.

- The term Cubo-Futurism is applied to a range of Russian art seen to have synthesized the influences of French Cubist and Italian Futurist painting. However, some critics have pointed out that the influence of Italian Futurism was relatively slim, and have instead emphasized the importance of prior developments in Russian art such as Neo-Primitivism and Rayonism to the conception of Cubo-Futurist style. Amongst the various painters associated with the movement, however, Rozanova was uniquely indebted to Italian models, including the work of Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla. This connection was reflected in the display of her work in an exhibition of international Futurism in Rome in 1914.

Important Art by Olga Rozanova

In a Café

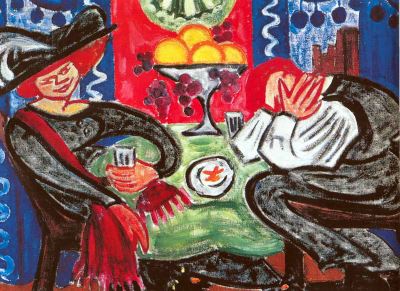

This relatively early work indicates Rozanova's awareness both of the French avant-garde art being exhibited in Moscow at the time and the Neo-Primitivist aesthetics of her Russian contemporaries, including Natalia Goncharova. Reminiscent of works depicting the louche café-culture of Paris, by Paul Gauguin, Edgar Degas, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and others, In a Café nonetheless retains a distinctively Russian, Neo-Primitivist aesthetic, tapping into the historical tradition of folk-art already being mined by Goncharova and others by this time.

Critic Nina Gurianova describes works such as In The Café as possessing a "laconic, expressive, and vivid childlike manner", referring in particular to the "deliberately crude and straightforward" painting style, for which various reference-points can be cited. Rozanova's interest in all-over decorative patterning, for example, is reminiscent of the Fauvist Henri Matisse's domestic scenes, while the use of bright color-contrasts in preference to blacks and greys in order to indicate areas of shadow is similar to Matisse's Blue Nude of 1907. The thick outlines and flattened perspectival space, and the bold and jarring use of color in general, are comparable both with Matisse's work and with that of the German Expressionist movement.

But Rozanova combines the innovations of her French predecessors with a focus on dramatic color contrasts which bears the traces of her own, unique style, with an apparent view towards using color to represent the scene's emotional cadence. The vibrant reds connect the woman's scarf to her hands, hair, and face, and the café-wall to the face and hands of the man on the right. The male dining companion buries his face, suggesting, in combination with the female diner's almost malevolent grin, either an emotionally taxing conversation or very different physical reactions to the drinks held in their hands.

Oil on canvas - State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

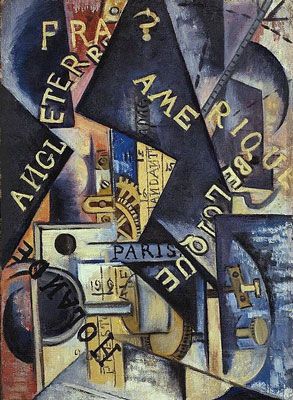

The Factory and the Bridge

Nina Gurianova describes The Factory and the Bridge as representing one of the "purest variant[s] of Russian futurist painting." It was one of four works by Rozanova included in the First Free International Futurist Exhibition, held at the Sprovieri Gallery in Rome in 1914, and designed to showcase the international spread of the Futurist movement.

The Factory and the Bridge foregoes accurate compositional arrangement in favor of a dynamic, centralizing visual unity. Structural tension is established by the intersection of the zig-zagging bridge-lines with the sharp, jagged planes representing the factory buildings, while vibrantly juxtaposed red and blue planes occupy the center of the canvas. The burnt-red smoke stacks just above anchor the image in figurative representation, as do the circular shapes spreading across the painting, which suggest the wheels of old-fashioned vehicles, seemingly split in two by the sheer force of productive activity. In this work, Rozanova clearly expresses the formal and thematic influence of Italian Futurist painting, depicting, like Umberto Boccioni or Giacomo Balla, a jarring contrast between modern and pre-modern elements of urban life, while also employing a Futurist-influenced visual lexicon of fractured planes and sharp diagonals. As in the Futurist painters' work, industrialization, urbanization, and mechanization are presented as noisy, irresistible forces of progress, and the overall mood of the piece is almost violently celebratory.

Again however, Rozanova adds her own signature style to the avant-garde aesthetics of her day. Combining bright yellows and warm reds with cooler blue tones, set against the dull greys and whites of the bridge, her color-palette is arguably more Expressionist than Futurist, predicting her later use of abstraction to represent the dynamism of an inner, spiritual energy rather than that of machines and automobiles. Nonetheless, whereas In the Café indicates the French (if not exactly Cubist) influence on Rozanova's Cubo-Futurist style, The Factory and the Bridge suggests the far more central inspiration which she drew from Italian Futurism.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Metronome

Rozanova's 1914 painting Metronome was shown at The Last Futurist Exhibition 0,10 in Petrograd in 1915, alongside such legendary works as Malevich's Black Square. This painting is an exemplar of the Cubo-Futurist style which defined the middle-stage of Rozanova's career.

Like both the Futurists and the Cubists, Rozanova integrates text into her work, arranged in this case in diagonal and curved lines spreading upwards across the canvas. We can posit an affinity with the "Word Paintings" of the Futurist Carlo Carrà, including his Interventionist Demonstration completed the same year, though the Cubists Picasso and Braque had been experimenting with the incorporation of written messages and found texts into their paintings and collages from an earlier point. The fractured, angular planes which define the picture-surface, and the emphatic use of chiaroscuro to define and delimit those surfaces, are equally suggestive of French and Italian precedents, while the representation of clock gears, winding mechanisms, and bolts, indicates the piece's subject-matter.

Again, it is possible to identify unique elements in Rozanova's interpretation of the Cubo-Futurist aesthetic. Nina Gurianova suggests, for example, that the theme of the clock-mechanism reflects the artist's interest in "achronic consciousness", the infinity and perpetual motion of historical time, a concept also explored by contemporary religious philosophers such as like Nikolai Fyodorov and Pyotr Ouspensky, suggesting the spiritual and esoteric underpinnings of Rozanova's work.

Oil on canvas - State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

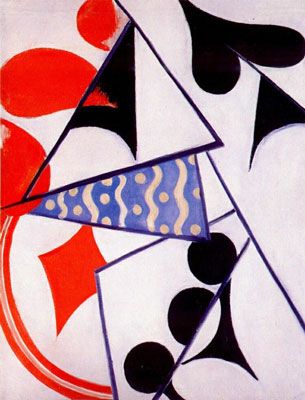

Simultaneous Representation of Four Aces

This work is part of Rozanova's eleven-painting cycle Playing Cards, described by Nina Gurianova as having "no counterpart in either Russian or European painting." The series was first shown at the Exhibition of Leftist Trends at the Dobychina Bureau in St. Petersburg in April 1915; the Last Futurist Exhibition would be held at the gallery later that year. This painting combines aspects of Rozanova's early Neo-Primitivist aesthetic with a form of Cubo-Futurist abstraction which is increasingly detached from clear figurative representation, predicting the style of her later works.

Playing cards were a common Russian Neo-Primitivist motif, everyday objects associated with urban leisure culture, but also possessing more mysterious connotations connected to Russian peasant traditions of magic and card-reading. From works such as Mikhail Larionov's Soldiers Playing Cards (1903) onwards, Neo-Primitivist artists had transformed playing cards into romanticized objects, and Rozanova's series is partly a nod to that native tradition. At the same time, the term "Simultaneous Representation" may refer to the vibrant, Orphic paintings of the French artists Robert and Sonia Delaunay, described by Robert Delaunay as "simultanist" paintings. That term indicated an attempt to relay multiple views on a single object, with a particular emphasis on the different ways objects absorbed or reflected light across the day. If this aspect of Orphism can be compared to Rozanova's later, more purely abstract color-works, in this instance her "simultanism" is whimsically suggested by her offering abstracted views of the four "Ace" cards in the deck - unlikely to all appear at once during a game of cards - as well as what seems to be a section of the patterned reverse of one card.

The Playing Cards series represents a critical step on Rozanova's path towards pure abstraction. Elongating or truncating the cards to the point of distortion - so it is not clear, even on the terms of abstract art, what the painting's subject-matter is - and working with an already abstractly 'patterned' object, Rozanova begins to move beyond the figurative Cubo-Futurism of works like Metronome, towards a form of painting in which identifiable subject-matter is entirely dissolved.

Oil on canvas - State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

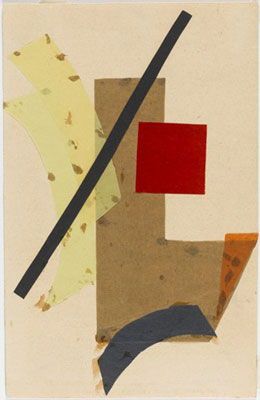

Non-Objective Composition

Collage-based works such as Non-Objective Composition were the precursor to Rozanova's later painterly abstractions. Indeed, she felt that such works, with their elementary, overlapping shapes, and textural play with translucency and opacity, were the inspiration for Kazimir Malevich's turn towards "non-objective" abstraction with his first Suprematist canvases of 1915.

Rozanova's collage-work anticipates her later Suprematist work in its incorporation of simple, non-representational shapes such as arcs and rectangles. But the compositional technique also points to international sources: like much of the work of her French Cubist and Italian Futurist predecessors, Rozanova's collage-work blurs the boundaries between painting as a two-dimensional illusion and painting as a non-representational, three-dimensional surface (potentially incorporating found and 'non-artistic' material). What was different about Rozanova's collage work was the aesthetic logic behind that maneuver. Whereas Picasso's use of found materials in his Synthetic Cubist collages collapsed the boundaries between high and low art, and the incorporation of printed text into Italian Futurist collage-work often signaled an overtly political agenda, Rozanova was more interested in the abstracted color harmonies which could be emphasized once painterly representation had been done away with. The new shapes and tonalities created by the overlapping of surfaces represent an exercise in the interplay of unmodulated color planes, a form of practice-based research into the interaction of color.

Non-Objective Composition is thus a vital work both in pointing towards the Malevich-esque abstractions of Rozanova's final years, and in his revealing her own, central and under-acknowledged role in shifting Russian avant-garde art towards the aesthetic stance of Suprematism.

Collage on paper - Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

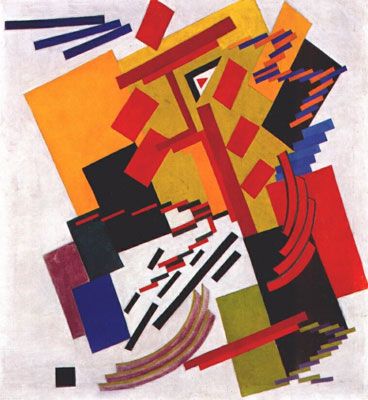

Suprematism

This painting is, as its title suggests, a good example of the late work which Rozanova produced in conjunction with the Suprematist movement. But Rozanova's approach to Suprematism is distinguished by its emphasis on the vibrancy and interaction of color, an emphasis which might call to mind the Expressionist paintings of Wassily Kandinsky.

This particular piece seems more focused on the harmony and contrast of color than the relationship between geometric shapes so important to Malevich's first Suprematist works; or rather, those relationships seem coextensive with the interplay established between different tonal ranges. The primary color-contrast is between darker or more muted greens, blues, and blacks, and more vibrant reds, oranges, and yellows, with each darker or cooler color abutting or adjacent to a warmer counterpart. On the far right, for instance, a large red rectangle overlaps with a large black rectangle, with the four red arcs outlined in black adding a directional motion, suggesting a formal link between the two color-fields. In general, warm and cool shapes are counter-posed positionally in ways that emphasize the opposition of colors, with red and black shapes seeming to stretch from top-left to bottom-right of the canvas, and blues moving in the other direction. The sense of visual motion and energy established by this interplay of color and shape reflects Rozanova's interest in expressing an inner, spiritual or emotional dynamism through her work.

Unlike the architectonic Prouns of El Lissitzky's Suprematist phase, then, or the pure geometric interplay of Malevich's contemporaneous work, Rozanova's Suprematist paintings are centrally concerned with, and dependent on, the study of color motion, expressed through a vocabulary of abstract shapes. In this sense, they represent a unique contribution to one of the most important genres of early-20th-century avant-garde art.

Oil on Canvas - Museum of Fine Arts, Ekaterinburg

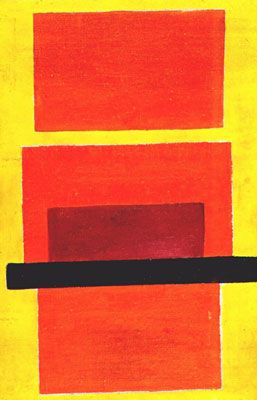

Abstract Composition (Color-Painting)

Abstract Composition, one of Rozanova's last works, illustrates her theory of what she called "transfigured color far from utilitarian goals". A meditation on the tonalities of red, orange, and yellow, this work suggests how color can bring emotional and physical associations to simple geometric forms. It not only epitomizes the technical and conceptual advances of Suprematism, but also predicts later developments in Concrete Art and Abstract Expressionism.

Set against a bright yellow background, the central arrangement of rectangles presents a kind of back-and-forth play between lighter and darker colors. The red-orange rectangle towards the top of the canvas imposes itself against the bright yellow background, while leading the eye downwards towards two nested rectangles sat on a black horizontal band. The incremental progression from light to dark suggests a subtle recession in depth, emphasizing the ways in which color can alter our perception of shape (while the black band furnishes the faintest suggestion of a landscape, perhaps with setting sun). Below is a further orange rectangle, whose subtle tonal distinction from the one above is emphasized by the thick dividing line; this implies how the arrangement of several colors can affect our perception of the constituent colors taken in isolation. This work shows the influence of - or at least an affinity with - Malevich's contemporaneous paintings, in its rough, hand-hewn feel, and in the way the white canvas shows through in certain areas. By exposing the canvas where particular shapes meet, Rozanova also seems to present those shapes as separate planes or surfaces, thus referencing the origins of her Suprematist paintings in her earlier collages.

Rozanova's last paintings are accomplished works of pure abstraction, which pre-empt better-known works produced later in the century. The emphasis on color interaction, and the use of nested rectangles, for example, might remind us of the Concrete artist Josef Albers's Homage to the Square series, while the overall structural arrangement and emotive use of color is very reminiscent of Mark Rothko's Abstract Expressionist aesthetic. Works such as Abstract Composition thus not only stand for a particular, pivotal moment in the development of early-20th-century avant-garde art, but also stand at the forefront of a whole century of abstract painting.

Oil on canvas - State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Biography of Olga Rozanova

Childhood

Olga Rozanova was born in the small town of Melenki in Russia, near the city of Vladimir, about 200 kilometers east of Moscow. Her father, Vladimir Iakovlevich Rozanov, was a district police officer, while her mother, Elizaveta Vasilevna Rozanova, was the daughter of an Orthodox priest, educated to a high level for a woman of her generation. Olga was the couple's fifth child, though only three of her siblings survived infancy. In 1903, Rozanova's father died, leaving Olga's mother as the head of the household. From 1896 to 1904 Rozanova studied at the Vladimir Women's Gymnasium, before leaving her home-town to train as a painter in Moscow, where her brother was already based as a law student.

Early Training and Work

Little is known for certain about Rozanova's early artistic education, but she definitely trained in private art schools in St. Petersburg and Moscow, working in the latter city under the tutelage of the Realist painter Nikolai Ulyanov, and with the Impressionist landscape painter Konstantin Yuon. The critic Nina Gurianova notes that Rozanova's early works are primarily distinguished by the artist's "unusual approach to the model," whereby Rozanova brings "into each drawing an individual, personal element of portraiture", indicating "on every page not only the exact date, but also the name of the model, often in a friendly, diminutive nickname...". By these and other means, Gurianova suggests, Rozanova aimed to capture in paint both the physical qualities and "overall inner essence" of her subjects. Many of her early works also depict the natural world, and as a whole her youthful painting style is characterized by crowded composition, and by a thick impasto technique lending a distinct sense of physicality.

Between 1907 and 1910, Rozanova embarked on what Gurianova calls her "first Moscow" period. During this time the artist worked on landscape, portrait, and still-life paintings with an attentiveness to color and decorative effect indebted - like much Russian avant-garde at this point - to Impressionist and Post-Impressionist techniques, in particular the work of Paul Cézanne. While in Moscow she was also exposed to the more general influx of French avant-garde art showcased at exhibitions such as the first Golden Fleece Salon of 1908, which included work by Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, Paul Gauguin, Jean Metzinger, and Georges Rouault. Rozanova was also able to view the famous collector Sergei Shchukin's holdings of Western European art, and was influenced by the work of her Russian compatriots Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, whose work would later be associated with so-called Neo-Primitivism. Uniquely for a Russian artist of her generation, Rozanova's artistic journey never took her beyond the borders of her home-country.

Mature Period

Rozanova was a member or fellow-traveler of various of the fugitive avant-garde movements and groups springing into existence in the heady atmosphere of pre-Revolutionary Russia, including the Union of Youth, Jack of Diamonds, and the Left Federation of the Professional Union of Artist-Painters. According to Gurianova, the years from 1911 to 1914 were "the four most intense and fruitful years in Rozanova's life."

In 1913, Rozanova was elected to the executive board of the Union of Youth - which by this point had expanded to incorporate various artistic and literary collectives - and composed the group's manifesto, "The Foundations of the New Art and Why It is Not Understood". Published in March of that year, this statement defines aesthetic beauty as a life-giving, ethical force, proclaiming freedom from creative convention as the only means of capturing and engaging with that force. Rozanova's was the first in a series of legendary Russian artistic manifestos written in 1913, including Mikhail Larionov's "Rayism", Aleksandr Shevchenko's "The Manifesto of the Rayists and Futurists", and the sound-poetry manifesto "Declaration of the Word as Such", co-authored by Rozanova's future-husband Alexei Kruchenykh. The ideas in Rozanova's manifesto were based partly on her study of a Russian translation of Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger's 1912 text Du Cubisme, as well as the 1910 "Manifesto of Futurist Painters" by the Italian artists Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla, and Gino Severini. Rozanova was also a talented poet, creating abstract and phonetic verse similar to the "Zaum" poetry being produced by Kruchenykh and Velimir Khlebnikov at this time.

The aesthetic of Rozanova's middle period is a striking example of what is now known as Cubo-Futurism, a term for various painting styles developed in Russia during the early 1910s which combined the ideas and techniques of French Cubism with a range of native influences and, at a later point and to a lesser extent, the influence of Italian Futurism. Cubo-Futurism is often referred to as one of the staging posts on Kazimir Malevich's journey towards the Suprematist style achieved with his Black Square of 1915 (itself based on a 1913 curtain design for the Cubo-Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun). But if works like Malevich's The Knife-Grinder (1913) wear the influence of Cubism on their sleeve, Rozanova's Cubo-Futurist aesthetic was unusual in its relative lack of reliance on French models, and for its unique affinity with contemporary Italian painting. Reflecting during 1916-17 on her formative engagement with Italian Futurism, Rozanova declared that the style had enabled the "fusion of two worlds - the subjective and the objective." Italian Futurism, she went on, "expressed the character of our contemporaneity", and represented an "event [...] destined never to be repeated." Her affection for the style was reciprocated: Rozanova's work was shown abroad for the first time in an exhibition of international Futurist art held at the Sprovieri Gallery in Rome in 1914. At the same time, while her work shows a clear engagement with the Futurist idea of depicting dynamic movement, it seems more concerned with evoking what Gurianova calls "inner, spiritual, movement" than with the speeding automobiles and airplanes which fascinated Umberto Boccioni et al.

Late Period

Following the dissolution of the Union of Youth at the outbreak of war in 1914, Rozanova, like many Russian Cubo-Futurist artists, began to experiment with purer, less figurative forms of abstraction. She turned to intensive studies of color, shape, and texture, and explored Wassily Kandinsky's theories on the spiritual and emotive content of abstract art. Color increasingly became the artist's primary concern, and her later works - like those of the German Expressionist movement - relied on dramatic tonal contrasts to convey emotional mood.

Rozanova exhibited at the so-called Last Futurist Exhibition 0,10, held in St. Petersburg in 1915, where Kazimir Malevich's Black Square made its debut, alongside early examples of Vladimir Tatlin's Constructivist sculpture. Writing to Kruchenykh after the exhibition, Rozanova declared that her collages had been the uncredited inspiration for Malevich's Suprematist style, which she described as "entirely [based on] my paste-ons: a combination of planes, lines, discs (especially discs) and no incorporation whatsoever of real objects. And after all that these scum hide my name." Despite the tone of this letter, Malevich and Rozanova were said to have enjoyed a close and productive professional relationship, Rozanova acting as Malevich's secretory while he worked on his unrealized magazine-project Supremus.

Malevich and Rozanova were often seen as working along the same stylistic path, but Rozanova's interest in color set the Suprematist work of her later years apart from Malevich's. During 1916-17, she worked on a theory called "tsvetopis", involving what she called a "transfigured" color scheme. This represented Rozanova's most concerted attempt to distance her aesthetics from Malevich's and to establish her own place in relation to the Suprematist aesthetic of the time. Roughly meaning "color painting," the idea of "tsvetopis" reflected Rozanova's belief in the primacy of color and color effects in the composition and activation of the painting surface. The catalogue for a 1992 retrospective of Rozanova's work describes her as having imbued Malevich's "decorative and spatial possibilities of abstraction" with a unique "feeling of color"; the Constructivist designer Varvara Stepanova, in a 1918 diary entry, claimed that Rozanova's work presented "her own, reworked movements of the soul and feeling", using "paint and color that was not mystical like that of Malevich." Indeed, it is worth noting that Rozanova, who also worked in embroidery, textiles, and graphic design, seems to have been a talismanic figure for a younger generation of Russian women artists such as Stepanova, whom Gurianov describes as having been "sincerely and deeply interested in Rozanova's work."

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, Rozanova became involved in political activism, and in 1918 helped to establish the Moscow branch of the Free State Art Studios (SVOMAS), Bolshevik art schools intended to extend artistic education and training to the worker and peasant classes, which Rozanova saw as reviving the role of the traditional Russian craft workshop. She was also at the center of debates between Suprematists and Constructivists in post-Revolutionary Russia as to which style should define the new artistic culture of the USSR. During preparations for one of the first post-Revolutionary exhibitions of Russian art, both camps tried to claim her as their own.

In the midst of all this activity, on November 8, 1918, Olga Rozanova died at the age of 32 from diphtheria, contracted while she was working on converting Tushino Airport into a domestic architectural space, a project intended to mark the first anniversary of the October Revolution.

The Legacy of Olga Rozanova

Art historian Nina Gurianova describes Olga Rozanova's art as "so whole and unique" that it "defies all attempts to enclose it within the bounds of any single tendency or group." Traversing various of the styles and aesthetic groupings which went into making up early-twentieth-century Russian avant-garde aesthetics, her brief career and its untimely end, Gurianova suggests, represent "the fate of the early Russian avant-garde [...] in miniature." The critic Charlotte Douglas notes that Rozanova's oeuvre was exemplary of its epoch in extending into applied and decorative arts; she received particular acclaim for her designs for books by poets such as Velimir Khlebnikov and Alexei Kruchenykh.

But although Rozanova was an important figure in the Russian avant-garde - one of the "Amazons" of early-twentieth-century Russian art, according to Cubo-Futurist poet Benedikt Livshits - her work has received little sustained critical attention except in Russian-language publications. This relative neglect stands in striking contrast to the reception of her work amongst her peers, such as Aleksander Rodchenko, who photographed the artist lying in her coffin in 1918. Other contemporaries described Rozanova's art as possessing a "gentle feminine elegance", and "full of diversity and promise", while a posthumous 1919 exhibition was visited by 7,000 people, with the Constructivist fashion designer Varvara Stepanova, the Suprematist painter Ivan Kliun, and the art historian Abram Efros either contributing catalogue essays or writing favorable reviews. Efros's article, published in 1919 and republished in 1930, remained the definitive scholarly text on Rozanova until the 1970s, in part reflecting the stultifying grip of Socialist Realism over Russian art across the middle decades of the 20th century. Even the writing on Rozanova that began to appear after that point was often riddled with factual errors and inconsistencies, but a more recent generation of critics such as Gurianova has helped to bring Rozanova's life and work back from obscurity - to some extent.

Influences and Connections

-

![Mikhail Larionov]() Mikhail Larionov

Mikhail Larionov -

![Natalia Goncharova]() Natalia Goncharova

Natalia Goncharova -

![Henri Matisse]() Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse -

![Umberto Boccioni]() Umberto Boccioni

Umberto Boccioni ![Giacomo Balla]() Giacomo Balla

Giacomo Balla

![Vladimir Mayakovsky]() Vladimir Mayakovsky

Vladimir Mayakovsky- Mikhail Matyushin

- Elena Guro

- Nikolai Kulbin

-

![Kazimir Malevich]() Kazimir Malevich

Kazimir Malevich -

![Lyubov Popova]() Lyubov Popova

Lyubov Popova ![Varvara Stepanova]() Varvara Stepanova

Varvara Stepanova- Aleksander Rodchenko

- Aleksei Kruchenykh

-

![Suprematism]() Suprematism

Suprematism -

![Constructivism]() Constructivism

Constructivism ![Cubo-Futurism]() Cubo-Futurism

Cubo-Futurism