Summary of Albert Gleizes

One of the founding fathers of Cubism, Gleizes was in equal parts artist, theoretician and philosopher. As a member of the so-called Salon Cubists, he was responsible for bringing Cubism to the attention of the general public and, with Jean Metzinger, wrote the first major treatise on Cubism, the hugely influential, "Du Cubisme". His was an uncompromising commitment to the movement and it was Gleizes who pushed Cubism towards its furthest point of abstraction. Driven by a faith in social idealism, he produced numerous writings that saw him progress the static, purely formal, aspects of Cubism towards something more animate and, ultimately, something more divinely spiritual. Gleizes helped found many important artistic societies and retreats, and, in later life, devoted his intellectual activity to exploring potential overlaps between Romanesque, Byzantine, Arabic, Celtic and modern art. Following his full conversion to Catholicism, he turned exclusively to religious paintings which he executed firmly within the Cubist tradition.

Accomplishments

- The standard for Analytic Cubism had been set by Picasso and Braque who had all but eliminated the "distraction" of color and any notion of a coherent, single perspective, art. Gleizes's early Cubist works retained both a faith in color and a noticeable element of spatial depth. Although it was an approach that didn't sit so well with the radical element of the movement, it was Gleizes and the other members of the Salon Cubists who announced this radical new movement to the world through their infamous "Salle 41" exhibition.

- Gleizes was amongst the earliest Cubist converts and, was part of the first Cubist Groupe de Puteaux. The group mounted the first ever major Cubist exhibition: La Section d'Or and it was augmented by Gleizes's and Metzinger's groundbreaking treatise Du Cubisme. It remains the only description of early Cubism written by the artists themselves. The double impact of the exhibition and the publication of Du Cubisme stands as a landmark event in the history of avant-garde art.

- Gleizes, a pacifist and social idealist, founded the artists' community Moly-Sabata in the Rhone valley as a retreat for people disillusioned with urban industrial society. Based on Gleizes's search for an "absolute truth" in art, it became "a place of freedom and friendship" and presented a riposte to the French cultural establishment. Dismissed by many as little more than utopian idealism, Moly-Sabata exists to this day as an artists' residency and in 2017 celebrated its 90th anniversary, making it the oldest active artist residency in France.

- Once Gleizes had fully submerged himself in the Catholic faith, his painting became absorbed by the search for the "pure affect". His previous works, in which the material and the transitory coexisted on a single canvas, gave way to works through which he pursued an elusive - or "socially indeterminate" - quality that was revolutionary as a way of renewing the viewers' relationship with the Christian piety through art.

The Life of Albert Gleizes

"I wish to establish the true history of Cubism whose beginning was not a matter of mere chance", wrote Gleizes; Cubism was not, he insisted, "something dependent on a throw of the dice", but for the history of art a "revaluation of all the values of whose absolute necessity no-one in these days can be in any doubt".

Important Art by Albert Gleizes

Paysage (Countryside)

In this early work, the twenty-one-year-old Gleizes had seemingly taken on board some of the influence of Impressionism. We see this in his brushwork and also in his choice of a single-perspective viewpoint; Gleizes places us in the midst of the foreground, at a safe distance from the pathway that centrally winds down. Yet at the same time there is a preference here for asymmetry and a compositional irregularity which lends his picture a naturalistic feel that ties it to the realistic traditions of landscape painting. The fluctuating sky, with clouds scudding and bellying on a windswept and bright autumnal day, sees Gleizes's exploring the effects of light, but this is countered by the repoussoir ("pushing back") effect of the group of trees on the right that unbalances the composition by edging the scene to the left out into the further distance.

The thick impasto of the foreground vegetation is quickly applied giving the image a tactile, material, grounding. We do see in the distance an impressionistic quality where the sky meets the land, and the elements seem to blend, but this effect also accurately represents the climatic tumult of a windy day. While the painting itself now seems rather conventional, Gleizes's "crooked" landscape signals a burgeoning artistic ambition for creating an individual vision. This is most evident in the trees that show a strong feeling of the importance of line, and in the sky with its rich in painterly qualities. These would both become recognizable tendencies in Gleizes's later work.

Oil on canvas - Fondation Gleizes, Paris

Bords de la Marne (Banks of the Marne)

This image might be considered one of Gleizes's best proto-Cubist works. It seems at first to reveal a growing concern with Fauvism and the paintings of André Derain or Henri Matisse. In this respect, Gleizes's sky, a bright crimson that is pock-marked with purples and blues, can be read as a vigorous expression of the artist's subjectivity. The opportunity to render his sky in sweeping brushstrokes is complimented by a young painter who announces himself in the bold purple diagonal band that jets ever upward to the right. This sky can be seen thus as an early attempt by Gleizes to announce himself.

In the Fauvist style, the impasto layering seems to thwart the orderly and conventional recession of the walkway into the picture space, particularly where it meets the boathouse; it almost stands up before the viewers' eyes. The shape of the great tree at the head of the receding trees, meanwhile, seems an unnatural topiary and anticipates Gleizes's Cubist work. His tree is drained of colour but this "muting" allows the artist to concentrate on other matters: specifically a concern with abstract forms and naturalistic tones. The curator Daniel Robbins wrote, that in his pre-Cubist "treatment of inclusive landscapes" Gleizes was trying to "solve the problem of balancing many simultaneous visions on a painted surface" and that he "mitigated the distortion of distance by linear perspective, by flattening the picture plane". When placed within arc of his career, the painting sits as early evidence of the artist's intuitive sense of compositional poise and expression that would soon come to dominate his creative thinking.

Oil on canvas - Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon

La Femme aux Phlox (Woman with Phlox)

La Femme aux Phlox stands as a revolutionary moment in Gleizes' art. A seated woman stares down intently reading and is flanked by two vases of flowers. After having seen Henri Le Fauconnier's Pierre Jean Jouve of 1909, Gleizes's artistic direction changed. Le Fauconnier's portrait flattened forms and compressed the picture space but Gleizes has moved beyond his inspiration with the help of examples by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. But in contrast to Braque and Picasso, whose Analytical Cubism was all but obliterating coherent representation in favor of picture fragmentation, Gleizes's forms are distinctly and immediately recognizable here. He uses the visible world and its objects as a foundation for the elaboration on his new obsession with form. The sleeve of the woman's garment, for example, is exploited as an exercise in volume using strong lines and contrasting tones. The vase to the left has a dense sculptural appearance, as is the woman's head that is the embodiment of her intense concentration.

Gleizes does not hesitate to introduce spatial depth to his nascent style: the woman's raised right arm itself recedes in space and prompts the viewer to look behind her to what seems to be a window. In tension with his spatial depth here is perhaps a contraction of time, as the folds of the woman's reading material suggests the movement of the turning of pages - a fusing of past and present via a physical expansion of the flat Cubist form. Robbins wrote, "Continuing his new interest in the figure, Gleizes strove to manipulate a genre subject with the same sobriety and broad scale that had always informed his landscapes [and that] exterior nature is here brought into a room and the distant vista seen through the window is formally resolved with a corresponding interior shape".

Oil on canvas - Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Les Baigneuses (The Bathers)

It is instructive to place this painting alongside Paul Cézanne's Les Grandes Baigneuses of 1906, of which Gleizes said, "He who understands Cézanne, is close to Cubism". Left unfinished in 1906 (the year of his death) Cézanne's Les Grandes Baigneuses speaks of a harmonious summer's idyll in a triangular composition framed by trees and echoed by the arrangement and physical disposition of the female bathers. Gleizes's composition is much more expansive, with his female bathers in several groupings or alone, and arranged across the fore-to-middle ground. This technique can be related to the Cubist concern with a pictorial density that covers every area of the painting; a technique that allows the viewer to be overwhelmed by a world of intense sensations. In each part of this work we see the forms of figures, of trees, embankment and distant city all jostling for their place in the Gleizes's tableau.

This picture is more expansive than the Cézanne, visually, but also socially. In the earlier work the idyll is confined to the secluded foreground with the social world relegated to the distant background. Gleizes's picture, on the other hand, introduces the bathers as part of modern industrial world. We can almost hear the faint conversations of their groups just as we can almost hear the water dripping from the sponge of the upright central bather, with its visual analogue of striated lines. But the wider industrial world is introduced through the schematic plumes of smoke emitted from the factories which are seen in the gap in the trees in the background. Gleizes's bathers may be at leisure but the toil of city life looms large.

The figures are heavily stylized with Cubist shapes and are not individuated, or perhaps only individuated by their actions and disjunctive sizes. The disjunction of scale creates multiple perspectives, even within the confines of the foreground, with each figure or grouping performing an individual narrative or gesture. This suggests multiple perspectives in space but also incongruent conceptions of time. At this time, Gleizes was becoming heavily influenced by the idea of simultaneity in the philosophy of Henri Bergson and we can see here a flux of activity, sights, imagined sounds all rising together within something still and permanent (a painting).

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

Composition for "Jazz"

After his discharge from the army in 1915, Gleizes moved to New York where his work took on the frenetic inspirations of life in that city, like the skyline, its advertising signs and, in this example, jazz music. In Composition for "Jazz" we can make out the rudimentary elements of two performers both of whom are adorned in extravagant headdress while holding their instruments. The nearest player to the left has his or her shoulders made unnaturally angular and the hand on their instrument, a brief combination of a straight line and a curve, is all-but completely abstract - perhaps calling to mind the figure of a musical note. Behind, the second player seems to be holding a double bass, its colour a rhyme with the white guitar.

The two instruments are aligned, crossing each other at a dynamic angle. This could indicate the free-form lines of melody and rhythm through which the genre of jazz thrives. Yet there are unifying elements in the picture too, which itself bears a musical structure. The guitar's fretboard stretches over the double bass creating a harmony of performance; both the musical performance and the performance of Gleizes's brushwork on one canvas. From the central crucible of the action in the picture - which is more a depiction of concerted action than of the actors - rippling colours and angled shapes emanate outwards. In particular, at the heads of the instruments (the brown streak just over the bassist's head and the cloud of gold at the head of the guitar) seem to be a visual simile for the ethereal nature of music and the inner experience of its pulsating (or "dancing") colors.

Oil on cardboard - Solomon R. Guggenheim

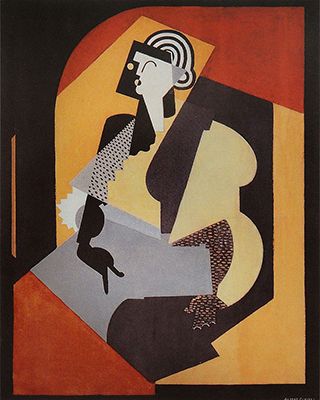

Femme au gant noir (Woman with Black Glove)

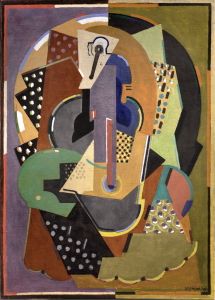

Following on from Picasso's Arlequin, and Juan Gris' Arlequin à la guitare, which were both painted in 1917, Gleizes produced this work in a similar style three years later. By comparison with his earlier Composition for "Jazz", the figure of the woman is much easier to pick out (than the jazz musicians). The woman here is looking upward with her geometrically regular head in fields of yellow, black and terracotta red. The black seems to form an arch around the figure, which points to a traditional framing of the portrait. Although the figure is immediately recognizable, the picture departs from a realistic portrait. It does not provide a mimicry of nature but seems to convey an essential aesthetic quality (the use of pure lines and stark tones) and perhaps a human idealization - in other words, it is rather a portrait of woman than a portrait of a particular woman.

The figure, in its spartanly drawn angles, seems to be the site of a competition between self-containment and unity on one hand, and division on the other. She is sliced by shapes of yellow and black that are juxtaposed rather than gradated. The titular black glove stands out on a grey background field in the shape of a scissor. This could be a painterly pun referencing the process of Synthetic Cubism (Picasso and Braque were fond of using puns in their work) which made use of painting, collage and extraneous objects. With his strict devotion to painting, one might argue, with equal conviction, that Gleizes was either a radical or a conformist. In either case, the painting is evidence of Gleizes's growing preoccupation with the two-dimensions of the canvas which was a clear departure from his earlier works which tended to incorporate panoramic perspectives. Femme au gant noir does emphasise the flatness of the canvas but also demonstrates, through the artist's dynamic use of angles, an engagement with the illusion of spatial depth. There is a dialogue emerging here between the limits of the medium of painting and the fullness of space.

Oil on canvas - National Gallery of Australia, Parkes, Australian Capital Territory

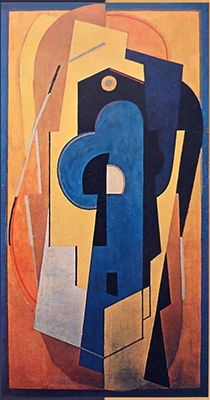

Composition bleu et jaune (Composition in Blue and Yellow)

By 1921, just a year after Femme au gant noir, Gleizes was probing a rather unconventional geometric abstraction in this large canvas. Almost nothing from the external world is visible here as we see angular forms arranged in a space.

Perhaps we can detect a relationship between figure and ground established by both the forms and colours. The dark of the black, and the deep blues, seem to body out, and suggest matter and things of the world; we can detect, perhaps, a basic gable end of a house with an oculus window towards the top and another receding rectangular window at the bottom. But, more than the "figure" of the painting doubling as a building, the shapes and colours are revealing as the remnants of the process of "building" the artwork. The gold and oranges of the piece can suggest the immateriality of light and could, by extension, be an effusion of Gleizes's push for an aesthetic spirituality. Gleizes sought to synthesize the visible with the aesthetic and the spiritual, and it seems here that that spiritual affect has distorted the visible into the apprehension of the "real", as he termed it.

Yet, in a more traditional vein, the artist has still preserved the perpendicular status of the figure in space, as if it were a portrait. Certainly, there is a Cubist deconstruction of the "figure" but, taken as an interconnection of forms, or rather a complex form itself, it is suggestive of a figure or object standing in a light-filled space of indeterminate proportions.

Oil on canvas

Figure en gloire (Figure in Glory)

Tradition and innovation again mingle in this mature work. We have a female figure, whose head is recognizable as such, surrounded by Gleizes's signature arcs and angled lines. The composition is doubly framed, on the outside by straight lines that are an internal echo of the shape of the board, and on the inside, by an ellipse of gradated colours from black to gold. The elliptical frame recalls a High Renaissance tondo such as those favored by Raphael. This could lead us to associate the female figure with a Madonna or perhaps a saint in rapture.

The expression of the colored and toned face is readable as an ecstasy of spiritual significance. The precise drawing of the face, framed by the blue square intensifies the emotion; as the surrounding colours and angles, while perceivable as the folds of drapery, seem to shift. The blue and beige of the face with its heavily stylized shapes make it less a face than a vessel for the communication of awe. As we know, Gleizes had by this time steeped himself in theological study and had become fascinated by the experience of pure affect. This picture exemplifies a step away from the synthesis of the visible and the "real" beneath it (as he had sought to formulate it). The haloed head of the figure, as the only recognizable "object" from the external world, is more a manifestation of pious elation and the picture as a whole a permeation of the material by the spiritual.

Gouache on board - Centre d'Art Espace Van Gogh, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence

Pour Contemplation (For Contemplation)

Pour Contemplation was painted as a part of a series entitled Supports de Contemplation (Aids to Contemplation). Shorn of all the social relevance we could detect in his early works, the picture still does not abandon the physical. Its concentric and peaceable curves appear as an apparition of a female form of both physical presence and metaphysical significance. In the knowledge of Gleizes's initiation into the Catholic Church just three years later, we can see here the form of an icon of the Virgin Mother. The figure is still featureless, though, and therefore elicits a certain projection on the part of the viewer.

As always, Gleizes is experimenting formally but he also maintained in his writings the productive confluence of the eye, the emotions and the laws of the universe. The eye travels into the picture's realm and the rationality of the forms is at ease with the ebb and flow of its wider world. Perhaps there is a landscape beyond the "head" of the figure. The black rectangles - Gleizes's characteristic rotations - seem to confer rational certainty. Yet within this there is indeterminate quality. For example, the rectangles could form a tangible pathway from the figure to the viewer as the universal "word of God" but they could also pave a way for the spectator to this ethereal plain through an act of faith. Gleizes has finally crossed from a philosophically informed spirituality to a total renewal of the Christian piety.

Oil on canvas - Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon

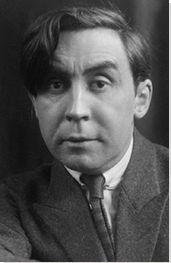

Biography of Albert Gleizes

Childhood

Albert was the son of a successful fabric merchant, Sylvan Gleizes (himself a keen amateur painter). His maternal uncle was Léon Commerre, an academic painter who won the Prix de Rome in 1875, while his father's brother, Robert Gleizes, was a successful collector-dealer specializing in eighteenth century paintings. The Gleizes' lived a comfortable life in Courbevoie in the Paris suburbs. Albert was very close to his two sisters, Suzanne and Mireille (he had an elder brother who sadly died in infancy), and they frequently appeared in his first paintings. Albert did not take to academic life and often played truant from his bourgeois school in Rue Chaptal, preferring to spend his days writing poetry in the grounds of the cemetery of Montmartre. According to the curator Daniel Robbins, when Albert's "authoritarian father discovered what was going on, he promptly put Albert to work in his design shop where he could personally supervise and discipline him". Gleizes willingly conceded later that "the necessary precision demanded by design was important to his artistic training".

Early Training and Work

In 1901 Gleizes was subscripted into military service, though he had already stated his desire to become a painter. This might have met with the approval of his father had he expressed a preference for academic training, but he was already demonstrating a rebellious streak through his allegiance to modernism. He began to paint seriously while serving in northern France and initially followed in the style of the Impressionists. He exhibited his first significant work, a landscape titled La Seine à Asnières (1901), at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1902. In 1904 he exhibited two further paintings at the Salon d'Automne, an annual exhibition designed specifically to promote the work of independent artists. Having completed his military service, Gleizes cofounded the Association Ernest-Renan; an enterprise through which he organized arts events such as exhibitions and poetry readings. The organization was anti-militarist and sought to provide culture in order to spread the ideas of pacifism at a time of heightened international tension.

While in the military, Gleizes made a close friend of the future poet Rene Arcos. The two men had developed an interest in symbolist poetry and the politics of democratic socialism. Both men believed fervently in the principle of a universal brotherhood fostered without the need for organized religion. Robbins suggests that until 1905, "Gleizes appears to have had little direct awareness of activity in the art world [and] even less contact with other painters". He admired the paintings of Pissarro, Seurat and Gauguin but these connections to his own work seemed rather "vicarious" when compared to "young painters like Braque and Picasso [and] even Metzinger and Delaunay [who were already] engaged in a struggle for recognition". Robbins adds that these young artists "learned the channels for success, the structure of relationships and contacts, the development of the gallery-centered art market, and they observed with interest the growth of various personalities and schools. The unsophisticated Gleizes [on the other hand] regarded the city as a bourgeois creation, a detestable place designed to trap artists as it trapped workers into a thousand evils, the worst of which would have been the corruption conferred by bourgeois approval".

Having completed their military service, Gleizes and Arcos became active in promoting utopian socialist politics and, in 1906, with the financial aid of Henri Martin Barzun, they established the Abbaye de Créteil, a phalanstery on the outskirts of Paris. Its members included the Symbolist poets Georges Duhamel, Charles Vildrac and Jules Romains and the community supported itself by publishing the writing of their members and others affiliated with the group. Robbins writes, "The Abbaye, whose fame circulated even in Moscow, attracted many artists. Marinetti and Brâncuși were visitors there and young writers like Roger Allard (one of the first to defend Cubism), Pierre Jean Jouve, and Paul Castiaux are typical of the artists who wanted to have the Abbaye publish their works. Nevertheless, after only two years, the Abbaye was forced to close, mainly because of material hardship. There simply was not enough money to keep going".

Through his involvement with the Symbolists, Gleizes's socio-political concerns were underscored by a deep sense of "symbolic reality". A newly galvanized Gleizes moved subsequently to Rue de Delta where he joined the society of Amedeo Modigliani and other avant-gardists. It was at this time that he dispensed with Impressionism, dropped his dalliances with Fauvism, and started to develop what would become his signature strong-linear style. In 1908 he produced Jour de marché à Bagnère-de-Bigorre, what Gleizes's biographer, Peter Brooke identified as his first "proto-Cubist" work.

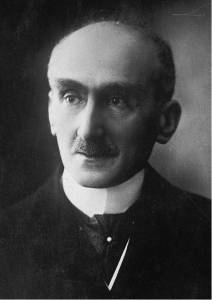

In 1909 Gleizes met painter Henri Le Fauconnier (a former student at the Academie Julian and a friend of Maurice Denis and Les Nabis) whose portrait of the poet Pierre Jean Jouve proved a revelation. Inspired by Le Fauconnier, a painter who was himself now working in the stylistic manner of Cubism's pioneers, Picasso and Braque, Gleizes adapted his style accordingly. Painted in 1909, his full-body portrait of Arcos, striding across a broad landscape, was Gleizes's first full experimentation with Cubism. He had adopted its preference for simplified forms, strong lines, and a restrained use of colour; a style that Robbins summarized as a "volumetric approach to Cubism" that featured a "successful union of a broad field of vision with a flat picture plane".

In 1910 both artists continued to concentrate on the human figure with Le Fauconnier producing a portrait of the poet Paul Castiaux, and Gleizes, a portrait of his uncle, Robert Gleizes. In the same year, the two men joined a group of artists who pledged earnest allegiance to the Cubist cause though they collectively baulked at Picasso and Braque's inflexible formalist rules that (as they saw it) limited Cubism's potential. Robbins noted that, for his part, Gleizes never set out (like Picasso and Braque) to "analyse and describe visual reality". For Gleizes still lifes - or rather "neutral objects from daily life" - could never "satisfy his complex idealistic concepts of true reality" and that Gleizes "always stressed subjects of vast scale and of provocative social and cultural meaning [and regarding] the painting as the area where mental awareness and the real space of the world could not only meet but also be resolved".

Mature Period

Gleizes, Le Fauconnier, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay and Fernand Léger committed to the investigation of form rather than follow the Post-Impressionist preference for flights of colour and symbolism. The group made history in 1911 when they exhibited in the infamous "Salle 41" ("Room 41") at the Salon des Indépendants. Their Cubist experiments, featuring four pieces by Gleizes, including La Femme aux Phlox (Woman with Phlox) (1910), drew large crowds, but a fiercely negative response from critics, including a review by Louis Vauxcelles who dismissed the group as "ignorant geometers, reducing the human form [...] to pallid cubes". The exhibition even garnered a response from the French Parliament that condemned Cubism as a "barbaric art". Speaking of La Femme aux Phlox specifically, meanwhile, the critic Jean Claude lamented: "A talented artist, Albert Gleizes, allowed himself to try a triangulist representation of the human figure. This is sad, deeply".

It is true that the five men were responding to the challenge to Post Impressionism already laid down by Picasso and Braque, but it was Gleizes and his partners who deserve the credit for introducing Cubism to the French public. The group was in fact able to count the poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire amongst their few professional allies after he praised them for hastening "la déroute de l'impressionisme" (the derailment of Impressionism). Indeed, Apollinaire's enthusiasm was such he became affiliated with Gleizes and his Cubist circle of friends.

In 1911 Gleizes met Picasso for the first time. Their meeting went a long way to confirming his rising star within the new Cubist movement which had been announced following the "Salle 41" controversy. Over the following two years his interest in the philosophical foundations of Cubist art developed and he soon fell under the influence of the popular French philosopher Henri Bergson.

Bergson had presented the idea of simultaneity, a science-based theory that proposed that two conflicting features - the permanent and the transitory - could coexist simultaneously. This idea proved inspirational for Gleizes who saw a way of applying it to Cubist painting. Gleizes declared that Cubism, unlike other "static" art, was "a normal evolution of an art that was mobile like life itself". Not content with addressing himself to strictly formal concerns, Gleizes started to explore ways of combining social and spiritual themes in a way that chimed with the likes of Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian. In Gleizes's view, art would help re-form the world according to the sensations of the individual; and in this utopian vision, color and form were, as they were for Cézanne before him, a unifying, rather than conflicting, force. The first results were works that captured movement from a multiple viewpoints, notably the vast Le Dépiquage des Moissons (The Harvesters) (1912).

In 1912, Gleizes joined Groupe de Puteaux, a cadre of artists working in a more broadly defined mode of Cubism than the one being proposed by Picasso and Braque. The Puteaux group, established by Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, met at Villon's house in Puteaux (on the outskirts of Paris) and occasionally at Gleizes's house in Paris. In the fall of 1912, the Puteaux group put on an impressive exhibition, "Section d'Or" ("Golden Section"), at the Galerie la Boétie in Paris. The name was suggested by Villon who was keenly pursuing an interest in mathematical proportions, and especially the ancient concept of the golden section (section d'or), as a way of perfecting the Cubist concern with geometric forms. For his part, Gleizes exhibited two pieces Women in a Kitchen (1911) and The Harvesters (1912). Robbins referred to the latter as "the masterpiece of the Section d'Or" that was "not merely an anecdote in a scene [but rather] "a multiple panorama celebrating the worker, his material life and his collective activity in securing that life on a permanently changing land. Gleizes confronts us not with one action or place, but with many: not with one time, but with past and future as well as present".

Such was the impact of the Section d'Or exhibition, it gave rise to a loose new association of artists that would involve the likes of Juan Gris, Robert Delaunay, Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Roger de La Fresnaye, Fernand Léger, Anndré Lhote, Louis Marcoussis and André Dunoyer de Segonzac.

Du Cubisme was an essay cowritten by Gleizes and Metzinger that was published in book form in 1912. It made a significant impact on the art world and was translated into several languages. The text was augmented by reproductions of works by eleven artists - Gleizes, Metzinger, Cézanne, Picasso, Braque, Léger, Duchamp, Gris, Picabia, André Derain and Marie Laurencin - all of whom had, to one degree or other, influenced or embraced Cubism. It is considered the first formal treatise on Cubist aesthetics (a revised edition was published in 1947 included a forward and epilogue in which the authors' explained their motivations for writing the original essay) and according to its authors it was intended to explain the influences and philosophy that defined the movement. Gleizes and Metzinger also argued the point that it was (or should be) the artist, rather than the critic, dealer or historian, who was best placed to articulate Cubism's precise goals.

In 1913 Gleizes took part in the famous Cubist exhibitions at the Armory Show in New York, the first overseas foray for the movement. It was in New York that Gleizes met his future wife, Juliette Roche. With the outbreak of the First World War in the following year, Gleizes enlisted as an entertainment organizer and worked in the role of impresario. While stationed in Toul, he painted Portrait of an Army Doctor (1914-15), a commissioned work for a doctor named Lambert who had made it possible for Gleizes to paint while enlisted. According to Gleizes, Lambert had been upset with the semi-abstract image and accepted a small gouache study by way of compensation. With the help of Juliette's father, a high-ranking government official, Gleizes was discharged from the army in 1915 and the couple moved to New York. Works such as Composition for "Jazz" (1915) and Broadway (1915) followed marking the artist move more and more towards total abstraction.

In 1916 the couple traveled to Barcelona where he held his first solo exhibition. But in the period leading up to his return to France in 1919, Gleizes began to allow religious ideas, and specifically the conflicts of conscience between a modern artist and a man of faith, to enter his thinking. In 1918 he reportedly announced to his wife: "A terrible thing has happened to me: I believe I am finding God". Following his epiphany, he decried what he saw as the arid aestheticism of Picasso and Braque's Cubism and declared that Cubism ought to advance down a more spiritual path.

Late Period

Having returned to Paris, Gleizes discovered to his consternation that Cubism had lost its ascendency and was giving way to the more "irreverent" movements, namely, Dada and Surrealism. Following an unsuccessful attempt to revive Section d'Or with a traveling exhibition in 1920, Gleizes slowly retreated from the public glare of the Parisian art scene, but he continued to paint and write in the name of the Cubist project. In 1920 he published Du Cubisme et des moyens de le comprendre ("Cubism and the Means to Understand It") and, in 1924, La Peinture et ses lois ("The Laws of Painting"). Gleizes continued to argue for the principles of Cubism and dismissed the illusionism of single perspective art as the enemy of true pictorial expression, arguing instead for what he called the "translation" and "rotation" of volumetric forms in space. In his practice, meanwhile, the 1920s was a period in which Gleizes produced what has been described as "post-Cubist" work - but "post" only in the sense that he was producing a highly abstract form of Cubism, as evidenced in works such as Ecuyère (1920-3).

Gleizes himself asserted that the function of art should never succumb to imitation, and that its "truth" comes from "individual sensibility and taste". He spoke of the many planes of a Cubist artwork as a "rhythmic organism" and that the true artwork was one that was "brought to life" through natural and aesthetic forms combining to make the image "spiritually human". But his fresh impetus did little to revive the fortunes of the movement that had been all but assigned to history. Robbins wrote, "Unlike Picasso [Gleizes] had neither participated in Surrealism nor returned to reality. Nor did he practice that most rational and ordered art, Neo-Plasticism. Although in many ways his theories were close to those developed by Piet Mondrian, his paintings never submitted to the discipline of primary colors and the right angle; they did not look Neo-Plastic" Robbins concluded that Gleizes "had never ceased to call himself a Cubist [and] a Cubist he remained [for the rest of his career]".

Juliette's father had died in 1923, leaving her a large portfolio of properties. Gleizes began to spend time at the house at Serrières where he became more immersed in theology thanks to an impressive library inherited from Juliette's great uncle, a former Bishop in the Diocese of Gap. In 1926 Gleizes father, Sylvain, passed away, and soon after he was involved in a serious car crash which left him hospitalized for two weeks. The couple sought to end their run of bad fortune with the purchase of Nostradamus's former estate in St. Rémy de Provence.

In 1927 the Gleizes' founded Moly-Sabata, an agrarian-based artists' commune in Sablons, a village close to Lyon. Moly-Sabata created a kind of community utopia that encouraged individuals to express themselves artistically, but also to share their ideas based on Gleizes's own conviction that art should strive for an absolute truth and, within the confines of Moly-Sabata at least, seek perfection in artisanal works. Life in the commune was often likened to a primitive monastic existence and, as a way of opposing the bourgeois art of the Salon, residents refused to engage with "social exhibitions" and were encouraged to "spread their truth" via purely oral and written means. (Between 1927-30, the retreat was managed by the painter/sculptor Robert Pouyaud, and between 1930-51, by the Australian painter and ceramist Anne Danger. It continues to thrive as an artists' residency to this day under the auspices of Albert Gleizes Foundation.)

In 1930 Gleizes published Vie et mort de l'occident Chrétien (Life and Death of the Christian West), in which he denounced the Industrial revolution on the grounds that it was incompatible with the Christian faith. He also traveled extensively during that time, promoting his theories of art in Poland, England, and Germany, even delivering a lecture at the Bauhaus where it was known that Kandinsky was in attendance. He helped organize anti-war meetings with the Unions intellectuelles françaises and, in 1932, he published Vers une conscience plastique: la forme et l'histoire (Toward a Plastic Consciousness: Form and History) in which he broadened his sphere of intellectual enquiry to include an examination of Celtic, Asian, and Romanesque art.

Around the same time, Gleizes joined Abstraction Creation, a group dedicated to an art of pure geometric abstraction in the vein of De Stijl and Suprematism. He collaborated with Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger and Léopold Survage, on Cubist murals for the 1937 World's Fair in Paris, and the following year (in order to raise funds to buy Moly-Sabata outright), he sold several paintings to the American art collector Solomon R. Guggenheim. On the eve of the outbreak of the Second World War, Gleizes started a second artists' commune, called Les Méjades, near the St. Rémy-de-Provence. Gleizes himself remained in France during the war and continued to work on a number of projects.

Having been confirmed by the Catholic Church in 1941, Gleizes began writing his memoirs (published in part as Souvenirs: Le Cubisme, 1908-14 in 1957) and produced a series of paintings on meditation called "Supports de Contemplation" (the shortages brought on by the Nazi occupation necessitated his painting on burlap). He followed in 1943 with a large triptych that encompassed: The Crucifixion, Christ in Glory and The Transfiguration. Gleizes's last works included a series of 57 original etchings for a new edition of the 17th-century philosopher Blaise Pascal's famous defence of the Christian religion, Pensées (1950), and a fresco, The Eucharist (1952), for the chapel at the new Jesuit seminary of the Fontaines community in Chantilly. Gleizes passed away in Provence in 1953 at the age of 71 following complications from a routine operation.

The Legacy of Albert Gleizes

Gleizes was never a party to the fame bestowed upon Picasso and Braque, but within the Cubist movement, he left his mark as probably its most serious and committed innovator. As a member of the Salon Cubists, he was in part responsible for announcing the movement to the European and American public, but it was through his application of mathematical and philosophical principles that he created a truly idiosyncratic vision that pushed Cubism to its furthest reaches. Indeed, his personal vision, which in the inter-war years saw him embrace metaphysics, breathed new life into a movement that to most modernists, in their incessant search for "the new", was a relic of an old avant-garde. As Robbins observed, Gleizes was one of the few Cubists "with a wholly individual style"; an artist, moreover, who "never repeated his earlier styles, never remained stationary, but always grew more intense [and] more passionate".

Given the ascendancy of others within the movement, it is for his theoretical analysis of Cubism that Gleizes confirmed his niche within 20th century French art. Du Cubisme amounted to the first philosophical and aesthetic justification for the Cubist project but it was only the first of numerous books and articles that investigated the formal, physical, and later, metaphysical possibilities for Cubist art. This led Robbins to the view that Gleizes was "perhaps the only painter of [the twentieth] century to have consciously struggled between the demands of reason and faith, in a reasonable - indeed a brilliant - manner and finally to have come down on the side of faith". He concluded that Gleizes's was "an abstract art of deep significance and meaning, paradoxically human even in his very search for absolute order and truth".

Influences and Connections

-

![Pablo Picasso]() Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso -

![Georges Braque]() Georges Braque

Georges Braque -

![Wassily Kandinsky]() Wassily Kandinsky

Wassily Kandinsky -

![Piet Mondrian]() Piet Mondrian

Piet Mondrian ![Henri Le Fauconnier]() Henri Le Fauconnier

Henri Le Fauconnier

- Mainie Jellett

- Evie Hone

- Robert Pouyaud

- Anne Danger

-

![Jean Metzinger]() Jean Metzinger

Jean Metzinger -

![Robert Delaunay]() Robert Delaunay

Robert Delaunay -

![Fernand Léger]() Fernand Léger

Fernand Léger - Léopold Survage

Useful Resources on Albert Gleizes

- Albert Gleizes: For and Against the Twentieth CenturyBy Peter Brooke

- Albert Gleizes: 1881-1953By Michel Massenet

- Albert Gleizes: The Birth and Future of CubismBy Pierre Alibert

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI