Summary of Analytic Cubism

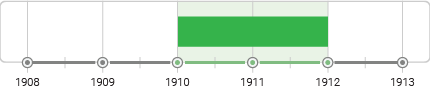

In 1920 the leading promoter of Georges Braque's and Pablo Picasso's work, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, published his book Der Weg zum Kubismus (The Rise of Cubism). It would become the first authoritative text on Cubist history and practice and it was here that the term Analytic Cubism was first introduced. Cubism was a movement that ran for close to two decades, but historians have tended to single out for special consideration its two most important phases: the Analytic phase (1910-12) and the subsequent Synthetic phase (1912-14).

Analytic Cubism defines a style of Cubism that fractured the subject into multi-layered, angular, surfaces that brought still lifes and portraiture close to a point of total abstraction. Following a two-year period of experimentation where Cubist artists took their lead from the faceted landscapes of Paul Cézanne, Picasso and Braque retreated to the studio where, over the ensuing two years, they honed the style of Analytic Cubism. The cadre of Cubist painters, meanwhile, have been put by critics into one of two camps: the "Gallery Cubists", namely Picasso and Braque, and a "second tier", the so-called "Salon Cubists", namely Juan Gris, Jean Metzinger, Fernand Léger, Robert Delaunay, and Albert Gleizes. Gris, however, would command equal status with Picasso and Braque when the Synthetic phase came to the fore.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- At a time when Impressionism had "progressed" from the avant-garde into the mainstream, and Fauvism was ruling the Salons, Picasso and Braque instigated an avant-gardist movement that would all but insist that the viewer re-evaluate the status of art. Using multiple perspectives to produce images that featured only snatched glimpses of everyday objects, the phase of Analytic Cubism initiated a way of thinking about art that went beyond the limits of fixed perspective compositions.

- Analytic Cubism brought a higher level of cognitive engagement to art. In a conscious decision to distinguish itself from the seductive styles of the Impressionists and the Fauves, Analytic Cubism's preference was for a limited range of colors and tones. Excessive color would have only served as a distraction from a style of art that was intent of encouraging the viewer/reader to analyse, rather than simply experience, art.

- In order to keep one foot rooted in realms of reality, Analytic Cubism introduced into its system of geometric grids and planes what Picasso called "attributes". Attributes were the fragments or details of everyday life; points of illusionistic reference that made the image aspects of the image accessible (realistically rendered) and thereby stopping the work from drifting into pure abstraction.

- Considered to be somewhat deferential to Braque and Picasso, the so-called Salon Cubists were nevertheless instrumental in broadening the appeal of Cubism beyond an elite class of art critics. Important historical figures such as Delaunay and Gris employed some of the techniques of Analytic Cubism but brought to their canvases a more luminous and energetic use of color. Through works such as Delaunay's Windows Series and Gris's Pears and grapes on a table their contribution allowed for a more wistful quality to impact on an art practice that had become, in the hands of Braque and Picasso, a strictly analytical practice.

The Important Artists and Works of Analytic Cubism

Violin and Palette

Art critic Roberta Smith observed that Braque's contribution to Cubism can be traced back to "his early training in his father's trade [...] which included sign painting and the painting of imitation wood and marble". His "apprenticeship" was, according to Smith, "clearly the basis for his interest in what he called the 'tactile' or 'manual' space of a painting". For his part, Braque explained that "When fragmented objects appeared in my painting around 1909 [as they do here] it was a way for me to get as close as possible to the object as painting allowed".

In what can be cited as a prototype of Analytic Cubism, Braque paints multiple picture planes in order to fracture and distort images of a violin, a palette, and sheet music. The arrangement of the objects emphasizes the canvas's vertical axis, while the limited color palette stresses (rather than distracts from) the overlapping forms, creating a density that seems somehow tactile. Braque would further emphasize the breaking down of the subject in this way it works such as Piano and Mandola (1909-10) which was described by art historian Jan Avgikos as, "an otherwise energized composition of exploding crystalline forms".

According to art historian Francis Frascina, Braque and Picasso's still lifes become "more difficult to decipher without knowledge of the systematic [language] that the artists appear to be using [and for] many Modernists, the works are on the 'threshold' of a formal development to abstraction", even though the artists themselves were seeking a "realistic orientation" through their work. We find clear evidence of this at the upper left of Violin and Palette, where we notice that Braque has painted a trompe-l'oeil nail, from which hangs the palette of the work's title. It is an illusionist technique that serves to illustrate the contrast between the nascent Analytical Cubism as measured against the traditions of single-perspective illusionism.

Oil on canvas - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York, New York

Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler

Broken down into planes and facets, and rendered in a limited palette of gray, black, white, and brown, we can begin to put together an image of Picasso's sitter (the art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler). The viewer can discern his clasped hands at the bottom of the frame, the knot of his tie, and the almost geometric intersection of the bridge of the nose with the eyebrows. Due to the intricacy of the overlapping opaque and transparent planes and the limited color palette the central subject takes on a kind of density that dissolves at the edges into the abstract background. As art critic Jonathan Jones put it, the famous art dealer "haunts [the painting] like a shadow of himself, a nuclear ghost imprinted in space [...] It is not a picture of him. And yet he is fully there, his identity glimpsed with a strange warm intimacy through the shattered glass of the modernist age".

Jones said this work was "Revolutionary and discomforting" and a masterpiece that brought on "a comprehensive dismantling of traditional portraiture" that was "intangible" and "indescribable". The difficulty in deciphering these near-abstract artworks, however, prompted several critics to refer to Analytic Cubism as a hermetic practice. This concept relates to the idea that the language of Analytic Cubism was so revolutionary it had no precedence in art history and was so airtight (so hermetic) it had to be learned from scratch. At the same time, what Picasso called "attributes," such as the wave of hair and the clasped hands (the more highly discernible aspects of the image), helped the viewer by anchoring the subject to reality giving her or him an initial point of reference; giving the viewer "something to build on", in other words.

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois

Nus dans la forêt (Nudes in the Forest)

Employing a somber palette of gray, white, grayish blue and green, this work is a complex and energetic layering of conic, cylindrical, and tubular planes. Léger described it in fact as a "battle of volumes" explaining that "I thought that I shouldn't give it any color. The volumes alone were enough". Though it is a landscape, which places it closer generically to the early phase of "Cézannian" Cubism, the painting is in keeping with the Analytic preference for a restricted color palette and a willingness to test the limits of figurative art. As if solving a picture puzzle, the trained eye eventually discerns the three nudes, one standing at the right and left and the other reclining on the ground in the center, and the resemblance of some tubular shapes to the trunks and roots of trees.

Léger's works take Cézanne's vision of a natural world composed of cones, spheres, or cylinders as the basis for a distinctive approach that also accommodates the mechanized forms of the modern world. Léger became associated with the Salon Cubists under whose auspices his idiosyncratic Analytic approach became a vital part of its aesthetic and theoretical explorations. As contemporary art critic Nechvatal put it, "Léger's early Cubist works are full of astonishing, automated, compulsive, and practically cinematic stutter effects". Léger subsequently developed his use of cylindrical and tubular shapes and a progressively bolder color palette to develop a signature style that became known as "Tubism". Nechvatal added, "his brand of Cubism evolved into an automaton-esque figurative style distinguished by his focus on cylindrical forms. These cylindrical android figures express a synchronization between human and machine that is most relevant today".

Oil on canvas - Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

Still Life with Banderillas

Braque painted this work in Céret, a village in the French Pyrenees, where he spent the summer of 1911 with Picasso. He recalled that during this period the two artists worked so closely together they often could not tell who had painted which work. Indeed, Braque later described how ''Picasso and I said things to one another that will never be said again [...] that no one will be able to understand". Given its subject matter - the complex intersection of multiple planes and angular shapes here evoke banderillas, the spiked sticks used in bullfighting - one might be forgiven for thinking that this piece was in fact painted by the Spaniard Picasso. Braque, a Frenchman, was not a fan of bullfighting but it is thought that the painting was conceived by him as a tribute to his close companion.

Historically the work is most noteworthy, however, because of the introduction of lettering and sand. As Braque stated: "I started to introduce letters into my pictures [since being two-dimensional they] were forms which could not be deformed". Letters therefore exist "outside three-dimensional space [and] their inclusion in a picture allowed a distinction to be made between [three-dimensional] objects which were situated in space and those which belonged outside space". In addition to the text, Braque includes sand (thereby incorporating another reference to the tangible world) to create texture and to emphasize the fact that a painting is a two-dimensional material object. As a result, this work can be classed as an early precursor of his and Picasso's move towards Synthetic Cubism which went much further in incorporating everyday materialist elements into their artworks.

The reluctance of the two men to let their works slip into pure-abstraction - to always declare in some way its links to a tangible reality - is not to suggest that their paintings were impersonal or lacked the element of intuition. It was in this aspect that the art historian Francis Frascina connects with the French philosopher Henri Bergson. According to Frascina, Bergson had had "an enormous cultural impact in France and beyond", promoting his ideas through prestigious public speaking events and through numerous books and articles. As Frascina noted: "Bergson's philosophy was profoundly anti-materialist and idealist. He claimed that 'reality' was that which 'we all seize from within,' that it is made up of each individual's experience and intuition of the world rather than external objectivity or 'simple analysis'".

Oil and charcoal with sand on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

"Ma jolie"

In its catalogue, the Museum of Modern Art in New York describes Picasso's painting as "A kind of stand-in for the woman who can barely be seen [and as such it is] one of the most complex, abstract, and esoteric images of its day". With its dark palette and its complex layering of multi-fractured planes, this work's analysis of pictorial space obscures its representational and anecdotal content. Only the density of the triangular forms in the center of the canvas, the six lines representing the guitar's strings, and the inclusion of a treble clef at the lower center, subtly suggest the subject of this deconstructed portrait. Indeed, the portrait is only made legible because of, in Frascina's words, "A narrow pyramidal 'scaffold' structure of the central figure [that] 'anchors' the faceted planes". At the bottom of the frame, meanwhile, the words, "Ma jolie", or "my pretty girl", reference both a refrain in a popular music hall song and the nickname of Picasso's lover, Marcelle Humbert. Yet the dark palette and aggressive fragmentation undercuts any sense of romantic or personal feeling, as the work becomes what Picasso called "a sum of destructions", a reference possibly to the move from Analytic to the more comprehensible Synthetic Cubism.

Veering once more towards abstraction, yet tethered tangentially to the representational, this work does indeed exemplify Picasso's "high" Analytic method. The famous art historian E. H. Gombrich had summed up the artist's goals when he wrote: Picasso "assumed that [the public] did not come to his pictures to receive elementary information. He invited them to share with him in this sophisticated game of building up the idea of a tangible solid object out of the few fragments on his canvas". He continued by saying that "artists of all periods have tried to put forward their solution of the essential paradox of painting, which is that it represents depth on a surface. Cubism was an attempt not to gloss over this paradox but rather to exploit for new effects". Yet coming as it did towards the end of a two year period of fervent creative endeavour, "Ma jolie" represents the apotheosis of Analytic Cubism; that is representative of a stylistic high point from whence the move towards Synthetic Cubism was all-but necessitated in the name of seeking out "new effects".

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

La Femme au Cheval (Woman with Horse)

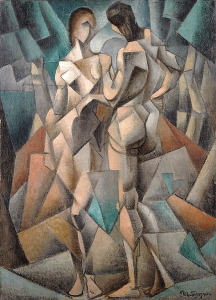

Metzinger's painting conforms to many of the stylistic preferences - multiple planes, volumetric, both rectilinear and curvilinear, forms - one would expect of an Analytic work. The nude herself is viewed both frontally and in profile while the horse is painted as if looking down from above. In the foreground, fragmented objects, including a vase and various fruits and plants are presented from multiple viewpoints too. But, as was typical amongst the Salon Cubists, color plays a stronger narrational role in this composition. Here for instance the brown shadows and luminosity of the figure and the warm grays of the horse bleed into the more subdued tones at the edges which evoke a forest setting. We even find dashes of luminous blue to represent the forest flowers.

Exhibited at both the Salon des Indépendants and Salon de la Section d'Or, this work was acclaimed by many, including Apollinaire, who subsequently included it in his only book The Cubist Painters, Aesthetic Meditations (1913). Metzinger was also central in developing the theoretical foundations of Cubism; his idea of the "total image" grounding it in the multiple subjective visions of the viewer. This work later even played a small role in the development of 20th century science when, in 1932, the noted Danish physicist Niels Bohr purchased the painting seeing it as the artistic expression and inspiration for his theory of quantum mechanics.

Oil on canvas - Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Windows Open Simultaneously (First Part, Third Motif)

Delaunay was considered one of the leading Salon Cubists following his exhibition, with Metzinger, Gleizes, Léger and Le Fauconnier, at the Salon des Indépendants in 1911. Though it is easy to discern the influence of the Analytical model in his near abstract, multi-planed view of the Eifel Tower, it is as much about the seductiveness (anathema to Braque and Picasso) of color. In this work, overlapping luminous planes, refracting bright colors bring the work close to abstraction, though one can finally discern the Eiffel Tower fusing at the center of the canvas. The composition's implicit geometric grid, fragmented through facets of color varying in tones and translucency, takes on an energetic fluidity; almost as if looking through the viewfinder of a kaleidoscope. As art historian Gordon Hughes wrote, Delaunay's Windows series demonstrates, "that vision, all appearances to the contrary, is precisely not like a window" while critic Bibiana Obler went further, suggesting that "Delaunay's paintings aim to incite awareness of the mediated processes of vision".

Delaunay's emphasis upon vibrant color, and what he called the "simultaneity" of modern experience (whereby the eye is asked to process a multiplicity of colors and shapes), were innovative additions to the development of Cubism and helped widen its popularity with the general public. This work also points towards Delaunay's transition to full abstraction, later named Orphism. Delaunay's work proved highly influential and informed works by the likes of Franz Marc, Paul Klee, Auguste Macke, and many others.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Beginnings

The Trailblazers: Cézanne and Seurat

Before Picasso and Braque had (seemingly) single-handedly reinvented approaches to pictorial perspective, Paul Cézanne had been the primary influence on the exploration of artistic form and plasticity. During the late 1800's Cézanne began to represent the landscape through spheres, cones and cylinders allowing for the various perspectives of the picture plane to lead the eye towards a dedicated focal point. As Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes wrote in Du Cubisme (1912), Cézanne's work, "proves without doubt that painting is not - or not any longer - the art of imitating an object by lines and colors, but of giving plastic [solid, but alterable] form to our nature".

The work of Georges Seurat, noted primarily for its expansive color palette and flattened depth of field, was influencing, albeit indirectly, the development of Cubism. As art historian Robert Herbert observed, "With the advent of monochromatic Cubism in 1910-1911, questions of form displaced color in the artists' attention, and for these [artists] Seurat was more relevant. Thanks to several exhibitions, his paintings and drawings were easily seen in Paris, and reproductions of his major compositions circulated widely among the Cubists". Viewing color as an independent formal element (as Seurat had) was consistent with Analytic Cubism's emphasis on composition and tone as separate elements. As Braque later confirmed, "we succeeded in dissociating color from form, in putting it on a footing independent of form, for that was the crux of the matter. Color acts simultaneously with form, but has nothing to do with form". Seurat's emphasis on flat linear compositions, created by fracturing the image into small dots of coloring, applied according to the current color theory, did, however, make a more obvious impression on the Salon Cubists; especially in the works of Gris and Delaunay.

Picasso and Braque

In 1907 Picasso painted his radical proto-Cubist work, Las Demoiselles d'Avignon. That same year Braque, who was already experimenting with the multiple-perspective approach of Cézanne, was introduced to Picasso (by Kahnweiler) and their historical collaboration had commenced in earnest. The two men forged a seven year relationship that was based both on a close friendship and a bitter professional rivalry. As Picasso stated, "Almost every evening, either I went to Braque's studio or Braque came to mine. Each of us had to see what the other had done during the day".

The two men came from quite different backgrounds: Braque's father was a painter and decorator who encouraged his son into the family business while Picasso's father was an academic painter who tutored his son in drawing. The two men had very different personalities too, Braque being a fiercely private individual who shunned publicity and remained married to the same woman his entire life; Picasso, who is often considered the first "celebrity" artist, was an egotistical, outspoken and unpredictable man who refused to settle for long on a single woman or a specific painting style. The two artists would, despite their differences, enjoy a period of extraordinarily productive collaboration that was unequalled in modern art, but which was ended, rather abruptly, in the fall of 1914 when Braque enlisted to the French Army as part of the war effort. (After the war the two artists never resumed their friendship and would even exchange barbs in public.)

The Dealer: Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler

Through his promotion of the Cubists, Kahnweiler would come to be recognized as one of the most important art dealers of modern times. By 1907 the German had already acquired paintings by Braque, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck and Kees van Dongen for his Galerie Kahnweiler (he was also a close personal friend of Matisse but his work commanded prices that were out of Kahnweiler's reach). A second ex-patriot living in Paris, Wilhelm Uhde, told Kahnweiler of a painting that had left him shocked. On his friend's advice, Kahnweiler visited Picasso's studio where he became mesmerized by Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (as it was named later).Though initially reluctant to sell, Picasso was won over by the German's genuine enthusiasm for his work and Kahnweiler would duly became the principle dealer for the Cubists, handling works by Picasso, Braque, Leger and Gris.

In 1914 Kahnweiler, who had till now naively refused to accept that France and Germany could possibly go to war, found himself an "official" enemy of France. His gallery was seized by the French state and the German fled with his family to Switzerland. On returning to Paris after the war he was forced to stand by and watch as the French state auctioned off his inventory as "war booty" with hungry dealers buying up the works at bargain prices (Braque had become so incensed at this travesty he actually attacked one of the unscrupulous dealers in the auction room). Kahnweiler would open a new galley (under a sponsors name), and he took on French citizenship but, being of Jewish ancestry, he had to flee the capital once more with the onset of the Nazi occupation. In the intervening years, however, Kahnweiler had delivered what would be his lasting gift to the Cubist movement: The Rise of Cubism (1920), a book which set the template for the movement's theory and practice. Indeed, The Rise of Cubism became a source book for the development of Modern art history and had a profound impact on the seminal text, Cubism and Abstract Art (1936), by the art historian, and first director of the Museum of Modern Art, Alfred Barr.

Concepts and Trends

Attributes

Analytic Cubism obscures, or hides, the subject of the work within the boundaries of a canvas that only reveals its origins by means of fragments or small clues. Picasso called these clues "attributes"; those being (in Picasso's words), "the few points of reference designed to bring one back to virtual reality [and which are] recognizable to anyone". Kahnweiler preferred the term "real details" to describe fragments of pipes, bottles, guitar strings and so on, that allowed the viewer to "construct the finished object in [their own] mind" and from whence he or she might then come to appreciate "an intensity of which no illusionistic art is capable". "Attributes", or "real details", would, from around 1911, even accommodate lettering. As art historian Jack Flam observed, "The appearance or words in Cubist paintings introduced passages of relative clarity into imagery that was [otherwise] often difficult to make out".

Synecdoche and Metonymy

A synecdoche is a literary or visual device in which a letter, a word or a part description represents the bigger whole: "glasses" are spectacles and "wheels" may be used to describe one's whole car, for instance. A metonymy (which will often overlap with symbolism) is similar to Synecdoche but in this case a written or pictorial abbreviation does not belong directly to the thing it stands in for: for example "the Oval Office is busy" (the "Oval Office" standing in for the people who work in it) or "let me lend a hand" (meaning "let me help"). The idea of the synecdoche and metonymy sat well with the goals of Analytic Cubism because it insisted that the viewer must engage with the artwork at a cognitive level if they are to make sense of it as a whole.

Sometimes a synecdoche was employed at a personal, playful, level as, for instance, by Picasso in his Violin, Wineglass, Pipe and Anchor (1912). At the top of the canvas, the artist paints a "W" and "BO" which act as a synecdoche for "WILBROURG", a nickname given to Braque by Picasso (Braque would sometimes even sign his name as "Wilberg"). The nickname "WILBROURG" was in fact a synecdoche in its own right since it referred to the pioneer of aviation, Wilbur Wright. The lettering offered confirmation of the fact that the two painters would often playfully call themselves the Wright Brothers after the famous aviators. Just below the "W" and "BO", meanwhile, Picasso paints "MA JO[LIE]" which, as an indirect reference, functions as a metonym that represents his nickname for his girlfriend "Eva" and also a popular hall room song.

The Pun

In the same vein as the synecdoche and the metonym, Picasso explored the idea of the pun. A pun is a jest that exploits potential misunderstandings between words that are alike but have different meanings. In The Scallop Shell: (Notre Avenir est dans l'Air) (1912), for instance, Picasso represents a café scene - scallop shells, a wineglass, a pipe tobacco, the corner of an aviation journal - from a visit with Braque to the coastal town of Le Havre (Braque's birthplace). On the right of the image, however, Picasso has painted the letters "JOU" (he had used these letters previously in other image combinations too). "JOU" is a slang abbreviation that could derive from any of the following:

Jou(ailler): to play a musical instrument badly

Jou(asse): the initial rush of taking drugs

Jou(er): to act the fool

Jou(eur): a participant in a game

Jou(jou): a plaything (toy)

Jou(issance): reach orgasm (to come)

Referring to Picasso's use of the pun, art historian Francis Frascina noted "we see evidence of a sign system which undermines existing expectations of stable meaning" suggesting, in other words, that the onus is on the viewer of the work to make their own sense of these puns. Indeed, recognizing a pun, and then trying to guess at the artist's intention, was in effect just one more means of prompting an act of analytic cognition from their viewer.

Color and the Salon Cubists

The Salon Cubists - Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Le Fauconnier, Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger and Juan Gris - earned their name due to their numerous exhibitions at Paris Salons. However, following Kahnweiler's Rise of Cubism, which identified Picasso and Braque as the rightful fathers of Cubism, the works of the Salon Cubists were relegated to a secondary position by critics (though their output has been reassessed with art historians such as Christopher Green suggesting that the demotion the group to a "satellite role" has proven to be a "profound mistake").

In 1911 the group exhibition in Salle 41 at the Salon des Indépendants (in what became known as the "Cubist room") proved a roaring success and launched Cubism on the international stage. In the following year, Metzinger and Gleizes published Du Cubisme, the first theoretical paper and aesthetic defence of Cubism through which they advocated the analytic method of "moving around the object" in order to create a "total image" in the mind of the viewer. However, while Picasso, Braque and the Salon Cubists were united in their preference for multiple picture planes and facets, the Salon Cubists chafed at the restrictive palette (the "muddy colors" as they called them) and duly employed a more expansive range of colors.

Later Developments

By 1912, Braque and Picasso had instigated the new phase of Synthetic Cubism as they lessened, or rather "de-emphasized", the fragmentation of the image while incorporating real materials, such as oilcloth or rope into their artworks. Yet, at different points in their careers, both men would continue painting works informed by the principles of Analytic Cubism. The Salon Cubists also evolved: Delaunay launched Orphism emphasizing bright, fractured shapes; Leger created his distinctive cylindrical forms dubbed Tubism; while Metzinger, Gleizes, and others created pure abstract works that emphasized the flat pictorial plane.

For its part, the fractured forms and planes of Analytic Cubism put in place many of the foundations of twentieth-century modernism. It directly influenced the development of Italian Futurism, Suprematism, Constructivism and, later, Purism and de Stijl, and informed innovations in sculpture and the architecture of Le Corbusier. Clement Greenberg's Decline of Cubism (1948) emerged a key text in acknowledged the historical importance of the whole history of the Cubist movement. As he said, "Cubism is still the only vital style of our time, the one best able to convey contemporary feeling, and the only one capable of supporting a tradition which will survive into the future and form new artists". The fractured, multi-dimensional, feature of Cubism - which reached its apex in the near abstract Analytic phase - also informed on other arts, notably in the films of Sergei M. Eisenstein and Jean Cocteau and the writings of Gertrude Stein, Blaise Cendars, and William Faulkner.

Useful Resources on Analytic Cubism

-

![Picasso and Braque's Cubist Experiment: "Like mountain climbers roped together"?]() 9k viewsPicasso and Braque's Cubist Experiment: "Like mountain climbers roped together"?Our Pick2012 / Lecture by conservators Claire Barry and Bart Devolde / Santa Barbara Museum of Art

9k viewsPicasso and Braque's Cubist Experiment: "Like mountain climbers roped together"?Our Pick2012 / Lecture by conservators Claire Barry and Bart Devolde / Santa Barbara Museum of Art -

![Picasso and Braque Symposium: The Different Facets of Analytic Cubism]() 5k viewsPicasso and Braque Symposium: The Different Facets of Analytic CubismLecture by Lisa Florman / Santa Barbara Museum of Art

5k viewsPicasso and Braque Symposium: The Different Facets of Analytic CubismLecture by Lisa Florman / Santa Barbara Museum of Art -

![Picasso and Braque Symposium: Un-Self-Contained]() 1k viewsPicasso and Braque Symposium: Un-Self-ContainedLecture by Charles Palermo / Santa Barbara Museum of Art

1k viewsPicasso and Braque Symposium: Un-Self-ContainedLecture by Charles Palermo / Santa Barbara Museum of Art -

![Cubism: The Collaboration of Picasso & Braque 2014]() 7k viewsCubism: The Collaboration of Picasso & Braque 2014Our PickLecture by Leonard Lauder / Aspen Institute

7k viewsCubism: The Collaboration of Picasso & Braque 2014Our PickLecture by Leonard Lauder / Aspen Institute -

![Reasonable Cubism - Salon Cubists, Albert Gleizes Man on a Balcony]() 4k viewsReasonable Cubism - Salon Cubists, Albert Gleizes Man on a BalconyLecture by Michael Taylor / Philadelphia Museum of Art

4k viewsReasonable Cubism - Salon Cubists, Albert Gleizes Man on a BalconyLecture by Michael Taylor / Philadelphia Museum of Art -

![The Mona Lisa of Cubism Jean Metzinger Tea Time]() 8k viewsThe Mona Lisa of Cubism Jean Metzinger Tea TimeLecture by Michael Taylor / Philadelphia Museum of Art

8k viewsThe Mona Lisa of Cubism Jean Metzinger Tea TimeLecture by Michael Taylor / Philadelphia Museum of Art -

![The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde 2012]() 56k viewsThe Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde 2012Lectures by Emily Braun, Wanda M. Corn, Edward M. Burns, Richard L. Feigen

56k viewsThe Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde 2012Lectures by Emily Braun, Wanda M. Corn, Edward M. Burns, Richard L. Feigen -

![The Cubist Cosmos - From Picasso to Léger / Kunstmuseum Basel]() 2k viewsThe Cubist Cosmos - From Picasso to Léger / Kunstmuseum Basel2019

2k viewsThe Cubist Cosmos - From Picasso to Léger / Kunstmuseum Basel2019

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI