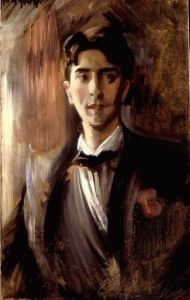

Summary of Jean Cocteau

Jean Cocteau worked across almost every artistic discipline, exploring writing, painting and drawing, theatre and film, linking disparate forms of art making in explorations of myth, contemporary life, dream and sexual identity. Cocteau began as a poet but aspired toward the creation of worlds into which an audience could be immersed. He drew from many influences, filtering the world around him through his personal sensibility and life experiences. Cocteau, though controversial among his peers due to his eagerness to please, valued collaboration and his receptivity to the ideas of others is evident throughout his body of work, which broke new ground in creating links between different styles, media and periods.

Accomplishments

- Cocteau aspired to create "total works of art," extending Richard Wagner's concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, then more familiar in theory than in practice, combining words, images and movements in multiple dimensions. This led him to direct ballet and film, illustrate his own books and decorate interiors, all of which provided the possibility of immersing the audience in his creations. This attitude to art making, which involved many collaborators, set the tone for the avant-garde later in the century.

- Jean Cocteau's work is often personal, mapping his own perspective onto the universal through reimagining myth in contemporary life, resulting in novel perspectives on familiar situations. Cocteau avoided the overtly political, favoring the escape from life offered through explorations of dream and the unconscious.

- Cocteau's work is divisive due to his difficulty fitting into established categories. He was unpopular, in his lifetime, due both to homophobia and to his obvious desperation for attention, but his habit of working across many media meant critics discredited him as failing to master any single discipline while fans praised his ability to work beyond arbitrary limitations.

- Cocteau was deeply depressed for much of his adult life and used art making, along with opium, as a means of coping with this. His work is indicative of his struggles, regularly exploring the possibility that creativity itself is inseparable from despair.

- Jean Cocteau's work is regularly described as 'surreal,' though he was never affiliated with the Surrealist group. Cocteau, like the Surrealists, was interested in exploring dreams and the unconscious and his mythologization of everyday life is similar to that of key figures such as Louis Aragon and Luis Buñuel, with whom he was on friendly terms. André Breton, the leader of the Surrealist group, however, viewed Cocteau's Romantic aesthetic as conservative and as anathema to the Surrealist creed of pure automatism and this, exacerbated by personal disagreements and Breton's homophobia, meant that Cocteau and the Surrealist group denied all links, despite their artistic similarities.

The Life of Jean Cocteau

Cocteau was a celebrity in his time and his disastrous romantic liaisons were widely discussed (one spurned lover shot himself, one died under the Gestapo, another became a monk). His reputation at times preceded him, even causing him to lament "my name has overtaken my work."

Important Art by Jean Cocteau

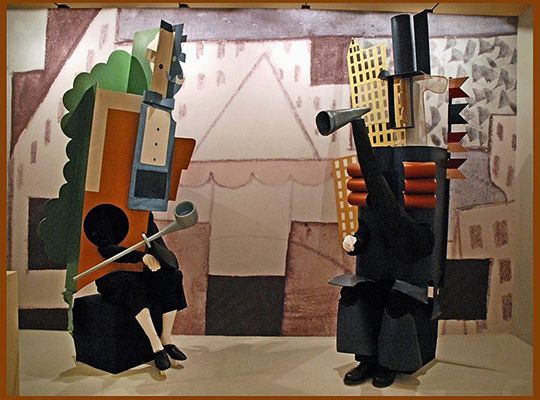

Parade

This image shows two of the costumes from Parade in front of the set background, both costumes designed by Pablo Picasso under Jean Cocteau's direction. The ballet followed three groups of circus performers attempting to lure an audience to a performance. These costumes, made from cardboard, were abstract and brightly colored; the figure on the left is a French businessman, identified through his pipe, while the figure on the right is an American businessman, with a red shirt, top hat and megaphone, with yellow and orange grids representing skyscrapers. The set resembles a child's drawing, with simple shapes suggesting fairground architecture. The score included sound effects, such as typewriters and sirens, interspersed with orchestral music.

Cocteau conceived of the ballet, which he pushed for the Ballets Russes to perform, as a work in which everyday life would, for the first time, be danced; he saw performance as offering an opportunity to bring literature, music, dance, sculpture and painting together into an all-encompassing artwork, creating an immersive world. Cocteau conceived of the scenario and wrote the libretto, selected Erik Satie as composer and worked with him - and sometimes against him - on the inclusion of sound within the music and enlisted Pablo Picasso to work on sets and costumes. Parade can be seen as a response to Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's call for the circus to invade the theatre, combining the popular entertainment of the dance hall with the classical language of ballet.

Illustration from The White Book

This drawing shows two torsos joined at the belly button, with facial profiles detached and turned, such that they do not flow from the bodies, but are linked by a line extending between the eye of the face in the lower left corner and that in the upper right. The image is from the 1930 edition of The White Book, a combination of autobiography and fiction exploring homosexuality which featured seventeen drawings accompanying the text. The text traces the erotic awakening of a young boy, while the images center upon anonymous male bodies. The narrator cannot be clearly linked to any of the figures, who are notably fragmentary, often rendered without hands or feet and with grey patches obscuring their genitalia, alongside a text in which Cocteau does not refer to the penis by name, instead using euphemisms ranging from "an enigma" to "that little underwater plant."

The book's central image shows the outline of two men, in similar postures, pressing their bodies on alternate sides of a mirror. The illustrations before and after this center similarly correspond, such that the book itself foregrounds doubling; the above illustration, also, with its doubled torso and multiple faces, suggests sexual eroticism springs, in part, from the allure of the mirror. The images are colored with soft pink, pale blue, dark grey and beige, though the colors do not correspond with reality, with some bodies left uncolored while others are blue or pink.

The White Book borrows, for its title, a phrase used to designate a set of official documents addressing a problem, as homosexuality was undeniably seen at this time; the word 'white,' however, has connotations of innocence, suggesting that the book operates essentially as a defense, as is supported by Cocteau's argument, in the text, that his "misfortunes stem from a society that condemns the rare as a crime and forces us to reform our inclinations." Cocteau's simultaneous avowal and disavowal of the text's authorship is in keeping with the tone adopted by the book, which celebrates homosexuality whilst accepting the inability to speak of it openly, as hinted at by the anonymity of most partners mentioned in the text and by a drawing of two men blindfolded. The centrality of the mirror image links The White Book with Cocteau's broader oeuvre, in which he frequently deployed mirrors to signify passage into the unknown. The colors used for the illustrations, in 1930, are clearly influenced by Cocteau's friend Marie Laurencin, known for working in a similar palette, while the fluid lines and abstraction of the figures show Picasso's influence. Cocteau revised the illustrations as his sexuality shifted; while the bodies drawn in 1930 are fragile and graceful, those accompanying the 1947 edition celebrate strength and virility, with far more explicit depictions of sexual acts.

Les Enfants Terribles

Les Enfants Terribles, published in 1929, centers upon siblings, Paul and Elizabeth, who isolate themselves as teenagers, playing a 'game' with one another that governs, disrupts and ultimately ends their lives. The central characters are based on Jean and Jeanne Bourgoint, twins with whom Cocteau was close, while the setting borrows from Cocteau's own living space, a room filled with photographs. It is easy, also, to read Cocteau's own way of being into that of the siblings, who are more imbedded in dream than reality, with confusion over the boundaries of the imagination and difficulty making sense of adulthood. Les Enfants Terribles introduces two other figures, Dargelos and Agathe, to this relationship, aggravating it with sexual competition. This image, a line drawing that shows two figures composed of one green line, meeting at lips, forehead and chest, was made for the cover of the 1963 reprinting.

Cocteau wrote Les Enfants Terribles in only seventeen days and expected that only a few people would read the book; instead, it was a popular and critical triumph. Cocteau's success was quickly complicated, however, by the death of Jeanne Bourgoint later in 1929, for which many blamed Cocteau, feeling that the suicide was designed after that of the book, despite reports that the siblings had not recognized themselves. Nonetheless, Cocteau did not distance himself from Les Enfants Terribles, as indicated by the cover he drew for the 1963 edition, which emphasizes the closeness of the book's central characters, who lack boundaries such that many critics mistakenly believed the novel to involve sexual, alongside emotional, incest.

Still from Blood of a Poet

This still from Blood of a Poet shows blood streaming from the head of the film's Poet, played by Enrique Rivero, who has just shot himself, in the penultimate scene from which the film takes its name. He wears a crown of leaves and draped scarves; to his left is a shadow appearing as an abstract face, traced on the wall behind. Cocteau's film is dreamlike, beginning with a man discovering a speaking mouth in the palm of his hand, which he slides over his body, moving downward from his face. He awakens to find a statue, played by the photographer Lee Miller, who encourages him to dive through a mirror which leads to a corridor where he looks through keyholes, seeing different worlds in each room.

Cocteau saw filmmaking as akin to drawing or writing on a grander scale, allowing the creation of worlds. He took full advantage of the possibilities of film to imitate the feeling of a dream, using slow and reverse motion along with positioning cameras above the sets in order to create unusual perspectives. Cocteau deliberately exhausted his performers so that they would appear, with tired movements, like sleepwalkers. This was heightened by the frequent use of black backdrops, creating a sense that the film's imagery and characters were suspended in space. Blood of a Poet was, alongside the work of René Clair, Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, among the first films constructed as artworks, making full use of the medium to subvert both space and narrative progression.

Still from The Infernal Machine

The Infernal Machine is a rewriting of Sophocle's Oedipus Rex, which follows the titular figure as he becomes King of Thebes through, unbeknownst to him, killing his father and sleeping with his mother; upon discovering what he has done, he gouges out his eyes. Cocteau combined the classical story with conventions from popular theatre in order make it contemporary. Cocteau used familiar, casual language; Jocasta, Queen of Thebes, for example, calls the High Priest Tiresias 'Zizi' and comments on the attractiveness of a guard, asking Zizi to "feel his biceps." Once again, Cocteau's interest in collaboration served the play; Coco Chanel designed the costumes, which combined classical simplicity with modern materials and shapes, while Christian Berard designed the sets, which had a geometry ideal for combining the tragic story with the playful, prosaic language.

Cocteau's interpretation of the Oedipus mix indicates the way in which he used his own life to give depth to mythology and to shape his own interpretations. The play, written at the denouement of his love affairs with both Jean Desbordes and Natalie Paley, is a contemplation of childhood's role in love's failures and on personal agency. Cocteau portrays Oedipus as innocent, condemned by an oracle and tricked by the gods, bearing no responsibility for his actions toward his parents. He is typically read as an autobiographical figure, reflecting Cocteau's guilt around his silence about his father's death and the weight of his mother's love; like Oedipus, Cocteau viewed himself as special, or chosen by the gods, only to struggle with the question of whether it was creative success or personal misery that made him special or if, perhaps, the two were inextricably linked.

Still from Beauty and the Beast

Beauty and the Beast, based on a fairytale written two centuries earlier, follows a young girl, Belle, who is trapped in a castle by a Beast with whom she eventually falls in love, discovering finally that the Beast is a transformed Prince. Jean Marais plays both the Beast/Prince while Belle is played by Josette Day. The film begins with a plea to the audience, by Cocteau himself, to suspend adult belief, watching the film as a child might; the opening credits, which are presented on a chalkboard and erased by Cocteau as he speaks, emphasize the audience's immersion in the world of the film. There is little dialogue in Beauty and the Beast, but the opulent details create a fantastical environment; candelabras are held by human arms which reach up from a table covered in jewels and fruit, while stone caryatids embedded in the architecture have moving eyes and breathe smoke. Belle and the Beast are, however, notably real, with pronounced chemistry between the two actors, aiding the audience's suspension of disbelief.

Jean Cocteau drew upon the illustrations of Gustave Doré in his representation of the Beast's castle, while Jan Vermeer's paintings act as a reference point for scenes, at the beginning of the film, set in a light-filled farmhouse. Cocteau places a different emphasis on the end of the story than is common in other interpretations, shooting Jean Marais as the Prince in a saccharine style, intended to undercut his conventional good looks, such that the disappointment of a fairytale ending, in which the heroine leaves romantic drama for marriage and children, is brought to the fore. Beauty and the Beast has been subject to a range of interpretations, with some critics arguing it offers a commentary on France during World War II, presenting occupation as an evil yet seductive spell, while others see it as a meditation on the conflict between creativity and contentment. Cocteau himself saw Beauty and the Beast as exploring the ways in which the unconscious shapes the pursuit of a particular type of man repeatedly and as an exposure of fairytale ideals, including conventional good looks and marriage, as naïve. Cocteau's work draws its ongoing impact in part through the degree to which it remains ambiguous, allowing for a wide range of intended and unintended readings.

Cocteau's fresco decoration of Chapelle Saint-Pierre in Villefranche-sur-Mer

Cocteau's work on the Chapelle Saint-Pierre in Villefranche-sur-Mer consists of a group of five frescoes, covering the building's interior, along with external decoration of the doors and the design of the altar and candelabras. This fresco, at the altar, depicts a scene from the Gospel of Mark, in which Christ anoints Saint Peter as Patron Saint of Fishermen. Cocteau renders the scene with fluid lines; the figures are shown with simple garments and shifting proportions that serve to emphasize Christ's divinity. The architectural features of the chapel are highlighted with playful geometric patterns tracing their edges. The frescoes, drawn in charcoal, are colored with subtle pinks, whites and blues.

Cocteau discovered, in 1956, that this Romanesque chapel, where fishermen preciously kept nets, had recently been restored and pushed for permission to paint it, wishing for a distraction from depression and loneliness. Cocteau saw the chapel as a site for escaping reality; he was not religious but was interested in all belief systems, including Christianity, for the ways in which they blended the mythical with the everyday. The separation of the space from the outside world is emphasized by the soft colors, which create a restful mood, while the depiction of Saint Peter and the primacy of the sea, behind the altar, serves to elevate the daily activities of the fishermen into a celestial realm. The Chapelle Saint-Pierre extends Cocteau's existing drawing practice into three-dimensions, with the same fluid lines and simple figures that characterize his illustration work appearing on an immersive scale.

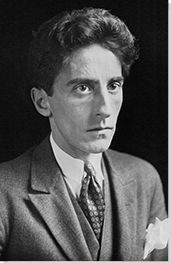

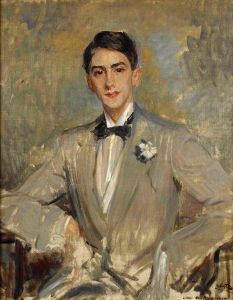

Biography of Jean Cocteau

Childhood

Jean Cocteau was born to Georges Cocteau and Eugénie Lecomte on July 5, 1889, in Maisons-Laffitte, a small town near Paris. He had a very solitary childhood, as his two siblings, Marthe and Paul, were both much older. Cocteau was nonetheless a happy child, spending summer in Maisons-Lafitte and winter in Paris, reading and playing, fascinated with fairytales and dressing in costume. The family were wealthy and Georges Cocteau, a lawyer, was able to quit his job early in Cocteau's childhood, spending his time painting and playing billiards while Eugénie Lecomte went to the theatre and posed for artists including Nadar (and his brother) and Jacques-Émile Blanche. Georges Cocteau introduced his son to drawing and the child earnt pocket money by selling his drawings to his grandfather. Jean Cocteau was ten when his father committed suicide, which created a harsh division between childhood and adult existence with which he would struggle throughout his life.

After his father's death, Cocteau was enrolled at the Lycée Condorcet, a private school. Cocteau struggled with his classes, succeeding only in drawing and gymnastics, and was eventually expelled for his repeated absences, after which he was given private lessons at home. Cocteau spent his teenage years close to the theatre; he created his own plays with René Rocher, a friend from the Lycée Condorcet, and the pair came to know actress Mistinguett, who courted the affections of her son's friends. Mistinguett later claimed that she was the first woman to sleep with Jean Cocteau, a story he neither confirmed nor denied, though he noted that his first sexual experience was with Albert Botten, a jockey, after which his mother warned him to think of the honor of the family. Cocteau failed the bac, the French high school diploma exam, twice and began to write poetry, in which his idealization of the past, fear of death and deep sadness is clearly evident.

In 1907, Cocteau and his mother moved permanently to Paris, settling in the city's northwest. Eugénie Lecomte, determined to remain a widow, shifted her affections onto her youngest son, who remained, like a child, unable to distinguish between myth and reality, imagining himself as the son of a foreign diplomat or an archaeologist. Cocteau's relationship with his mother left him practiced at pleasing others, creating an illusion of happiness out of fear that his sadness might be upsetting; the pair never spoke of Georges Cocteau's death.

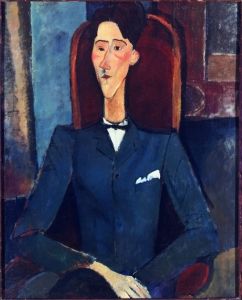

Early Training and Work

In Paris, Cocteau threw himself into the world of literary salons. He befriended Lucien Daudet, a novelist and painter, who gave him confidence and introduced him to a group of writers involved with Symbolism. At eighteen, Cocteau met Édouard de Max, a celebrated actor, who arranged a public reading of Cocteau's poetry. This gave Cocteau's mother confidence, only nine months after his second failure at the bac, that he had not inherited his father's weaknesses and she took him to Italy to reward him for this success. In Venice, Jean Cocteau had a brief affair with Raymond Laurent, who shot himself an hour after Cocteau left him on the steps of Santa Maria della Salute.

Upon return, Cocteau moved out of his mother's house and across the river, to a flat in the Hôtel Biron, where other tenants included Auguste Rodin and Isadora Duncan. Cocteau's love affairs were characterized by their unrequited nature, with the artist constantly on either side of mismatched passions. While living in the Hôtel Biron, he had a relationship with Christiane Mancini, a theatre student, which ended after she sent Cocteau letters detailing her desire and suffering. He was more successful professionally during those years, publishing two collections, Aladdin's Lamp (1908) and The Frivolous Prince (1910).

In 1910, Cocteau moved back to his mother's apartment in Rue d'Anjou. He began a relationship with Madeleine Carlier, an actress much older than him, who did not share his intensity of feeling, which ended when Carlier became pregnant and had an abortion, rejecting Cocteau's suggestion of marriage. Cocteau founded a journal, Scheherazade, which introduced him to contributors including Pierre Bonnard, Natalie Barney and Marie Laurencin. Cocteau met Maurice Rostand, with whom he had a relatively happy relationship; the pair were lovers, collaborated on poems, and became known for wearing outfits inspired by their shared love of the infamous writer Oscar Wilde to society events. Cocteau's closest friends during this period were Marcel Proust and Anna de Noailles, both of whom he worshipped and had deliberately sought out.

Cocteau was insistent in making connections that aligned with the art that he admired and wished to produce, pursuing collaborators with a persistence that often alienated others. After seeing Vaslav Nijinsky perform in 1909, Cocteau began to pursue Sergei Diaghilev, hoping to write the libretto for the Ballet Russes; he succeeded, in 1912, with The Blue God, which was a critical and popular failure.

In 1914, Cocteau presented himself to be enlisted, but found himself exempted from military service due to a weak constitution. Instead, he was instructed to collect milk from farms to give to troops departing to fight in World War I. After this, Cocteau joined Misia Sert, a Parisian socialite, on an amateur ambulance crew outfitted by fashion designer Paul Poiret. In 1915, Cocteau was sent to the front at Coxyde as an engineer; he took photos and drew, seeing war as dreamlike. His perspective, divorced as it was from the reality of war, led to his unpopularity with the soldiers. These experiences would inform Cocteau's novel about the war, Thomas the Imposter (1923).

World War I changed Cocteau's stylistic interests. He became interested in Cubism and distanced himself from Proust and de Noailles, who were becoming outdated, instead pursuing Pablo Picasso with gifts of tobacco and requests for portraits which went unanswered. Picasso eventually came to accept Cocteau, though hesitantly, and accepted his invitation to work on sets for Parade, which was performed in 1917, with music by Erik Satie.

Shortly after this, Cocteau met the fifteen-year-old Raymond Radiguet, with whom he became obsessed. Radiguet was protégé, muse, collaborator and unrequited love interest to Cocteau, who drew pictures of him as he slept, but was devastated by his uncertainty regarding Radiguet's feelings for him, eventually realising the teenager was exclusively attracted to women. Cocteau informed Radiguet's father that he would assist with Radiguet's literary future, which he did, introducing him to Bernard Grasset, who published his first novel. The pair remained close until Radiguet's death, from typhoid fever, at age twenty.

Throughout the 1920s, Cocteau was bullied by the Surrealists, who saw him as a symbol of the poetry they wished to destroy. Cocteau wrote to writer Louis Aragon, who was friendlier than others in the group, asking why "this nastiness, at once confused and meticulous," persisted, but didn't receive a clear answer; it appears that the enmity was driven by André Breton's homophobia and envy over Cocteau's friendship with the writer and critic Guillaume Apollinaire alongside distaste for Cocteau's floral prose and Romantic attachment to fairy tales. Cocteau received death threats from Robert Desnos, a central Surrealist writer, and disturbing anonymous phone calls during this period.

In 1926, Cocteau met Jean Desbordes, a lover with whom he would live until 1933. Desbordes inspired Cocteau to create work engaging more directly with his sexuality, the result of which was The White Book, published in an edition of only thirty copies in 1928. Cocteau was bisexual and demisexual, though he largely refrained from categorizing sexuality, but viewed homosexuality as nobler and purer than heterosexuality. Cocteau published The White Book anonymously, so as to avoid upsetting his mother, but signed copies for friends and acquaintances and illustrated the larger edition that appeared in 1930, tacitly admitting authorship.

Cocteau was using opium regularly throughout this period. In 1928, he entered a clinic in Saint-Cloud in order to cure himself of the addiction, writing Les Enfants terrible (1929) as a patient and Opium: The Diary of an Addict (1930) shortly after leaving. Cocteau befriended Jacques Maritain, a philosopher, and Charles Henrion, a Catholic priest, during this time. Cocteau continued to use opium throughout his life, feeling that it enhanced his artistic output.

Mature Period

In 1929, Marie Laure and Charles de Noailles offered Cocteau a million francs - quite a substantial amount for Cocteau, though a smaller budget than that granted to commercial directors - to direct a film, leading to The Blood of a Poet, completed in 1930. The film, ending with a child's death, caused outrage, with the Prefect of Police trying to prevent its distribution. In 1932, when the film was finally released, with some changes, the media referred to it as a "surrealist film," angering the Surrealists, who accused Cocteau of plagiarizing Luis Buñuel and waited outside his door, hoping to attack him physically.

Cocteau had moved toward theatre and film because he felt that he was failing as a poet and had been rejected by his friends of five years earlier. He withdrew to his room for much of the decade, replacing the world with his own inventions. In 1932, he met Natalie Paley, a married Russian princess, who shared his desire to escape reality; the pair embarked on an affair, fueled by opium, in which they left the house only to see Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich movies. This ended when Paley, imagining that she was pregnant, returned to her husband, devastating Cocteau. The mutually destructive escapism of this relationship illustrates the way in which Cocteau's life and work paralleled one another, with critics later commenting on the similarity to his earlier novel, Les Enfants terribles, which had, in fact, initially attracted Paley to Cocteau.

The onset of the Depression meant a lack of opportunities for artists to make films, but Cocteau continued to write plays throughout the decade, with those performed including La voix humaine (1930), The Infernal Machine (1934), The Knights of the Round Table (1937), Les parents terribles (1938) and La machine à écrire (1941). In the late 1930s, he also began writing popular songs and a column for Paris-Soir detailing his trip around the world in 1936. He became close friends with Edith Piaf, writing Le Bel Indifférent for her in 1940. Cocteau's work became unfashionable, however, as art took on an increasingly political role in the years prior to World War II.

In 1937, Cocteau met Jean Marais, an actor who would remain a close friend and intermittent lover for the remainder of his life; Marais would also star in many of Cocteau's later films. Cocteau's views on World War II were largely shaped by his anxiety about Marais, who was sent to the front in 1940 and subsequently joined the Resistance, and by his ongoing confusion about the relationship between art, identity and politics. In 1940, Cocteau was a supporter of the League Against Anti-Semitism, which led Louis-Ferdinand Céline, a prominent right-wing writer, to issue calls for Cocteau to be shot; in 1941, the 17th Squadron bombed a staging of Les Parents terribles with tear gas and released rats in the audience, ostensibly due to Cocteau's difficulty fitting within existing categories.

In 1942, however, Cocteau became friends with Arno Breker, a German sculptor who used his connections in the Nazi Party to intervene, at Cocteau's request, to remove Jean Marais's name from the Nazi death-list after Marais punched a rightwing critic. Cocteau wrote an article celebrating Breker's work, resulting in outrage amongst the Parisian artistic community; Breker, who had by this point been selected by Adolf Hitler as Official State Sculptor, temporarily persuaded Cocteau to support the Nazi Party, appealing to the poet's love of myth. Cocteau's attitude, throughout the war, was shaped by self-interest, not ethics.

Late Period

In 1945, Cocteau returned to directing films with Beauty and the Beast, starring Jean Marais. He consequently directed The Eagle with Two Heads (1948) and Les Parents terribles (1948). In 1950, he directed Orpheus, the second film, after The Blood of a Poet, in a set that would become known as the Orphic Trilogy. This starred Jean Marais, as did Cocteau's last film and the last in this set, The Testament of Orpheus, completed in 1960, which included cameos from a number of celebrities Cocteau had befriended, including Pablo Picasso.

Cocteau met Francine Weisweiller, who became a close friend and patron, while filming Les Enfants terribles in 1950, and moved to her home in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, where he would live throughout the decade. Cocteau decorated and painted the villa, making a film, La Villa Santo-Sospir (1952), about this project. Cocteau's lifelong work was recognized during this decade by his appointment as a member of the Belgian Academy in 1954 and the French Academy in 1955. He spent much of this decade painting, having found in it the ability to forget himself, providing some relief from his depression. He painted chapels in Villefranche-sur-Mer, Milly-la-Forêt, London and Frejus, a theatre in Cap d'Ail and a wedding room in Menton. He returned to Milly-la-Forêt, where he had kept a house with Jean Marais, shortly before his death in 1963.

The Legacy of Jean Cocteau

While unpopular with those around him, Jean Cocteau and his work have had a significant impact on a later generation. His influence on the Pop great Andy Warhol, who shared Cocteau's fascination with celebrity, his eagerness to borrow from the surrounding culture, his excitement about collaboration and his interest in moving between media, is particularly clear. Cocteau's combination of ancient and modern reference points, while controversial in his day, resonates clearly in postmodern experimentation with 'high' and 'low' culture; postmodern multi-media superstars Jean Paul Goude and Antonio Lopez's iconic Grace Jones Maternity Dress (1979) is, in both its aesthetic and relationship to performance, progeny of Cocteau's Parade.

Cocteau's influence can also be seen in the media in which he worked. Composer John Adams shared Cocteau's interest in combining contemporary life with rarefied art forms, as seen in his 1987 opera Nixon Goes to China. Director Bernardo Bertolucci's adaptation of Les Enfants terribles, The Dreamers (2003), shows his debt to both Cocteau's themes and habit of borrowing from those around him, while director Leos Carax's Holy Motors (2012) draws upon Cocteau's use of dream imagery in film. Tom of Finland, known for his erotic drawings, continues Cocteau's exploration of sexuality and the male body, while photographs by Pierre et Gilles similarly explore self-fashioning and desire.

In Cocteau's final years, he was offered the opportunity to create a museum in Menton, which opened as the Musée du Bastion in 1966, three years after the artist's death, featuring restoration work by Cocteau and a small collection donated by the artist himself. In 2003, the city began raising money for a more substantial museum of Cocteau's work, which opened in 2011, with a collection bequeathed by an American businessman, Séverin Wunderman. This museum, the Musée Jean Cocteau, is connected to and shares its collection with the Musée du Bastion, enabling rotating exhibitions that have introduced Cocteau's work to a new generation of Mediterranean visitors.

Influences and Connections

-

![Gustave Moreau]() Gustave Moreau

Gustave Moreau -

![Sergei Diaghilev]() Sergei Diaghilev

Sergei Diaghilev ![Filippo Tommaso Marinetti]() Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti- Robert de Montesquiou

- Gustave Doré

-

![Henri Laurens]() Henri Laurens

Henri Laurens -

![Pablo Picasso]() Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso ![Erik Satie]() Erik Satie

Erik Satie- Anna de Noailles

- Jacques-Émile Blanche

-

![Andy Warhol]() Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol -

![Robert Mapplethorpe]() Robert Mapplethorpe

Robert Mapplethorpe ![Philip Glass]() Philip Glass

Philip Glass- Tom of Finland

- Cerith Wyn Evans

![Jean Genet]() Jean Genet

Jean Genet- Marcel Proust

- Raymond Radiguet

- Jean Marais

- Edith Piaf

Useful Resources on Jean Cocteau

- Jean Cocteau: A LifeOur PickBy Claude Arnaud

- Cocteau: A BiographyBy Francis Steegmuller

- Jean CocteauBy James S. Williams

- An Impersonation of Angels: A Biography of Jean CocteauBy Frederick Brown

- The Difficulty of BeingOur PickBy Jean Cocteau

- Professional Secrets: An Autobiography of Jean CocteauBy Jean Cocteau

- Past Tense: The Cocteau Diaries Volume 1By Jean Cocteau

- Past Tense: The Cocteau Diaries, Volume 2By Jean Cocteau

- The Art of CinemaBy Jean Cocteau

- Opium: The Diary of His CureBy Jean Cocteau

- The journals of Jean CocteauBy Jean Cocteau