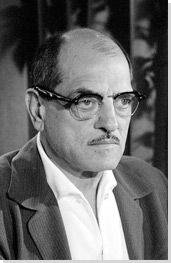

Summary of Luis Buñuel

Luis Buñuel pioneered Surrealist cinema, becoming the filmmaker who most successfully achieved the movement's goals of liberation from linear, logical narrative. Unlike many Surrealist films by other directors, such as Man Ray or Hans Richter, Buñuel is never "artsy" or stylized: there is an urgent, shocking, and visceral quality to his films - even at their most absurd moments. Buñuel went on to create harsh, unconventional realist films as well, but even in this mode his films contain startling juxtapositions of the real and the surreal. All of his major films, from Un Chien Andalou (1929) to That Obscure Object of Desire (1977), explore the torment and complexity of the human sexual need through uncompromising imagery. His films resist and criticize facile societal or religious solutions to the problems of human existence - his work at various times was derided with equal vehemence by the Catholic Church, Fascist Spain, and the Mexican Communist Party.

Accomplishments

- Surrealism broke new ground in literature through the practice of automatic writing, and in painting, it achieved startling but static dream-like images. Buñuel realized that the medium of film could go beyond painting and actually portray the disjointed visual narratives of human dreams in action. His first two Surrealist films capture the absence of moral filtering, the lack of will and logic that characterize the oneiric (dreaming) state, as if Buñuel had managed to place his camera inside actual dreams and record them.

- Buñuel's images of violence or cruelty are very successful at assaulting the viewer's complaisance, destroying comforting assumptions about existence and reality, and awakening the most basic and hidden fears lodged in the subconscious mind.

- His films provoke not only intellectual and emotional responses, but powerfully affect the viewer physically through repellent images of insects, bodily waste, decaying carcasses, amputation, and other shocking desecrations of human body parts. They involve and interact with the viewer in a way that is the hallmark of postmodernist art (many, many years later).

Important Art by Luis Buñuel

Un Chien Andalou

This silent short film, inspired by the dreams of Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, fulfills the Surrealist goal of achieving the pure automatism of the dream state, liberated from the constraints of reason, logic, traditional narrative, and temporal unity.

Un Chien Andalou shocks at multiple levels, showing acts of irrational physical violence, raw sexual desire, rotting animal carcasses, insects, and a complete violation of the fundamental rules of logical plot. In his Poetics, the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle had written that a work of literature or drama must consist of actions that arise logically out of each other, as well as preserve a unity of time and place. These rules of plot structure had dominated Western literature and theatre for centuries. But from the beginning, as they worked on their script at Dalí's home in Cadaques, Buñuel and Dalí agreed that nothing about the film could have a rational explanation. The resulting film has no narrative or linear logic. Skipping arbitrarily through time, "eight years later" and "sixteen years earlier," the film mocks and subverts the "title cards" that were used in silent movies to fill in temporal and narrative breaks.

There is no core narrative, although, if there is a constant at all in the film, it is an agonizing sense of sexual desire and sexual failure. Several of the film's images are among the most disturbing ever produced in the history of cinema: a razor slicing through a passive woman's eyeball, ants crawling out of an open wound on a hand, a woman's armpit hair turning into a man's beard, and many more. In the final scene, the romantic image of a happy couple cuts to an image of the same man and woman buried in the sand, the positions of their bodies or inclined heads reminiscent of Jean-François Millet's famous painting of 1859, The Angelus.

Both Buñuel and Dalí dismissed any attempts at analysis or rational meaning. Dalí wrote that the film "consists of a simple notation of facts... enigmatic, incoherent, irrational, absurd, inexplicable." In anticipation of a riot at the premiere in Paris, Buñuel filled his pocket with rocks to hurl at protesters - he later expressed his disappointment that a film aimed at offending the bourgeoisie was actually applauded by it.

L'Age d'Or

Buñuel's second collaboration with Salvador Dalí pushed the boundaries of decency even further. This film attacked the institutions that were considered the pillars of society: church, state, and family. The Surrealist combination of sex, violence, and truly bizarre images, made for confrontational viewing. Mocking the serious tone of documentaries, the film references the mating habits of scorpions, and features hapless bandits played by fellow Surrealists such as Max Ernst. In retelling a tale from the Marquis de Sade, the film's final episode casts Jesus Christ as the leader of the band of sexual libertines who have kidnapped and tortured young women in a castle. The film mercilessly mocks the clergy, shows the disrespectful manhandling of an ostensorium (one of the most sacred objects in the Catholic Church, the vessel that holds the Eucharistic host) as well as female scalps nailed to a cross. Other disturbing scenes include a father who shoots his little son for a ridiculously minor infraction, and the handsome lover in the film who beats up an old woman for spilling a drop of sherry on his suit. Outrageous as these scenes are, the characters seem to act as in a dream, without the restraints of reason. (Who has not committed terrible acts in their dreams?) A particularly strange scene, full of both a regressive, infantile orality, and outright cannibalism, shows the handsome lover and the young woman he desires sucking each other's fingers ecstatically instead of engaging in traditional coitus, and we discover at the end of the scene that the young woman has actually eaten most of the man's fingers; he caresses her with the almost fingerless stump of his hand. When he is called away, she resorts to sucking the toes of a classical statue in the garden.

If a continuous theme or narrative can be found in this film it is this couple's crazed desire for sex, which is persistently thwarted by absurd interruptions and petty annoyances. As in Un Chien Andalou, there is a nightmarish atmosphere of sexual desire, frustration, and failure. Buñuel achieved his aim to provoke: the crowd at the premiere rioted, destroying an exhibition of Surrealist paintings in the lobby. Le Figaro raged that the film was "obscene, disgusting and tasteless." The anti-Catholic themes were so upsetting that Dalí - who became a devout Catholic later in his life - refused to work with Buñuel again, and the Vicomte de Noailles, who had financed the project, was threatened with excommunication. The film was subsequently banned until 1979.

Los Olvidados

This film portrays the slums of Mexico City, where a group of street children live a life of murder, violence, poverty, and despair. Buñuel wanted to expose the reality of life here, and used Surrealist techniques to shock the audience - at one point an egg hits the camera and runs down the lens, breaking the fourth wall (thereby crossing the line between image and viewer, reminding us that we are watching a fictional story.) Other shocking scenes, reminiscent of L'Age D'Or, include the brutalizing of a blind man by the children as well as their destruction of a legless man's makeshift cart. The film reflects the Surrealist interest in pointing out the hypocrisy of accepted morality as well as the unrestrained actions of a group which, though brutal, is free from the controls of rationality. It explores the themes of sin and guilt, and in a stunning dream-sequence uses the techniques of superimposition and slow-motion to show the unconscious: chicken feathers fall as a mother walks holding a lump of rotten meat.

Buñuel screened this film first in Paris for his old Surrealist friends in the same cinema that had premiered L'Age d'Or twenty years earlier. The Surrealists loved his unsparing exposure of life's essential amorality - an issue that had always been at the heart of the Surrealist philosophy. It was shown at the 1951 Cannes Film Festival, where the accompanying brochure held praise from Andre Breton, and a poetic tribute from the Surrealist Jacques Prevert. Here, he was awarded the prize for Best Director. The film caused outrage in Mexico, however, where it was considered an insult to the country, to the point that Buñuel's Mexican citizenship was almost revoked. The Mexican poet and intellectual, Octavio Paz, defended the film passionately.

Viridiana

In this film, a young nun has a devastating encounter with her uncle who attempts to rape her but then commits suicide. He leaves her his house, and with her blind faith and trust in humanity, she decides to invite local beggars and lepers to share her home. This kindness is not repaid, and she is exposed to life's fundamental amorality, which corrupts her. The film's shocking tableaux vivant of Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper, with a blind Christ and sinful disciples, was denounced for blasphemy and banned by the Spanish authorities. This criticism of the Catholic Church reflects that expressed in L'Age d'Or, but in Viridiana he makes two clear points. Firstly, that naive faith in an institution such as the church or the innate goodness of people is foolish. The second point is about control - the Church is a symbol of oppression and attempts to crush natural human instincts, which can only lead to temptation and sin. The film ends with the woman with her hair down playing a game of cards - she has lost her innocence. The film uses Surrealist black humor to expose the fake morality of society. Despite the outrage in Catholic countries, the film was smuggled out of Franco's Spain to the Cannes Film Festival, where it won the 1961 Palme d'Or.

The Exterminating Angel

At an upper-class dinner party, the guests discover that they are mysteriously trapped in the room. It is an invisible barrier that traps them, not a physical one. It must be either magical in nature, or a shared psychiatric delusion. Trapped, their masks of social politeness rapidly fall away. This film picks up the key Surrealist theme of society attempting to control our true nature, despite the wild desires within. The primitive nature of the characters is exposed as they drop their social facades. In various ways, they try to find meaning or solutions. Some become argumentative, some depressed, some hysterical. Under the surface of polite society they are all savages. Random and inexplicable events take place: a sleepwalker stabs a woman, several people commit suicide, wild animals appear, characters enact magical rituals. Buñuel as usual takes aim at the Church, the film ending with a riot on the streets as a flock of sheep enter a church. Despite constant attempts to analyse this and other of his films, Buñuel resisted interpretations, saying: "basically, I simply see a group of people who couldn't do what they wanted to do - leave a room".

That Obscure Object of Desire

At the start of this film, a man travelling on a train dumps a bucket of water onto a young woman. This shocking image is explained by flashbacks. This man is the aging Lothario, Mathieu, who has fallen in love and is sexually tormented by a much younger woman, Conchita. A wealthy man, he believes he should be able to buy her with money and gifts, and his failure to seduce her turns his frustration into obsession. This expression of desire is a key concept of Surrealism, which Breton called l'amour fou (mad love). The early Surrealist movement considered the female more powerful than the male for her sentient and imaginative abilities; woman often appears in Surrealist works as an erotic muse but also as a conduit to the world of the fantastic and the magical. (This central role of the female in Surrealism is one reason why Breton forbade homosexuals writers and artists from joining the official movement.) Buñuel greatly admired Breton's novel Nadja (1928), in which the narrator, juxtaposing texts and photographs, explores his obsessive love for a beautiful, mysterious young woman who is ultimately placed in a mental asylum (the tragic real-life story of Leona Delcourt.) "Beauty is CONVULSIVE," the novel ends, "or not at all." Buñuel chose to have two actresses play Conchita to show both sides of her personality, one elegant, sophisticated, the other that of a wild Spanish flamenco dancer. But in a surreal touch, while the audience can see that she literally is two people, Mathieu does not. His sexual frustration is illustrated with Surrealist images and juxtapositions: a rough brown hobo sack reappears throughout the film, sometimes absurdly as Mathieu's sack (replacing his luxurious briefcase) or in the window of a fancy store for fine lace, Conchita wears a medieval chastity girdle that the exasperated Mathieu cannot unfasten, a pig is carried like a baby by a Spanish gypsy, a fly swims in a cocktail at an expensive bar, a mouse is killed in trap as Mathieu attempts to explain his feelings to Conchita's mother, and most shocking of all, senseless acts of terrorism are carried out by a group that calls itself "The Revolutionary Army of The Baby Jesus." Conchita in a sense terrorizes Mathieu sexually, at one point forcing him to watch her have sex with another man, though later she claims that the man was a homosexual and that nothing at all happened. The confusion of fantasy and reality, the violent depiction of frustration, and the inconclusive ending of a terrorist explosion, suggest the destructive power of unfulfilled desire.

Biography of Luis Buñuel

Childhood and Education

Buñuel was born into a wealthy and devout Catholic family in Calanda, Spain. It was a place of deep faith, where many literally believed in 'The Miracle of Calanda', in which an amputee had his leg restored by the Virgin Mary. Buñuel's strict Jesuit education equated sex with sin, a connection that, once made, ran deep and never left him. Buñuel also saw the divide between rich and poor, noting that poor children would stare open-mouthed at their luxurious home. By sixteen, he had doubts about the logic of the Bible, seeing the impossible conflict between human desire and the Church's taboos, and how this forced people into hypocrisy and self-deception.

At seventen, he went to Madrid to attend University. He originally enrolled to study Agricultural Engineering but, finding it dull, he instead spent a year indulging in his childhood passion for Entomology (insects) at the Museum of Natural History, before eventually studying Philosophy. Spain at this time was experiencing a powerful intellectual and artistic resurgence, and Madrid was a dynamic cultural capital. Buñuel lodged at Madrid's famous "Residencia de Estudiantes" (literally, "Student Residence"), a progressive educational institution founded in 1910, where some of the most talented Spanish intellectuals of the period converged, such as the Nobel Prize-winning poet Juan Ramon Jimenez and the philosopher José Ortega y Gasset. Guest lecturers included Albert Einstein, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, and the composer Igor Stravinsky.

At the Residencia, Buñuel met fellow-lodger Federico García Lorca, a young poet of extraordinary promise. The two would form a close friendship. Buñuel credited Lorca with introducing him to the secrets of poetry and to "a wholly new world." For a brief time, Buñuel was engaged to another poet, Concha Mendez, who broke off the relationship because of what she called his "insufferable character." Buñuel's friendship with Lorca was disrupted by the arrival in 1922 of the young painter Salvador Dalí, with whom Lorca soon became intimate, causing Buñuel considerable jealousy. Nevertheless, Dalí shared Buñuel's interest in dreams, sex, and the work of Freud, as well as in the relatively new medium of film. They especially loved American screwball comedies, such as Max Sennett's "Keystone Cops" films, which in their antics anticipate some of the irrational and chaotic events in Surrealist films. Buñuel was also impressed by German director Fritz Lang's film Weary Death (1921), which he claimed inspired him to become a filmmaker. Gradually, Buñuel and Dalí became closer, and together even expressed a certain disdain for the "old fashioned" folkloric elements of Lorca's famous Gypsy Ballads, which would be published to great acclaim in 1928. Lorca would later take offense at the title of their first film, Un Chien Andalou (1929), believing that the "Andalusian Dog" referred to him, a joke at his expense.

Early Career

Buñuel moved to Paris in 1925, where he went to movies obsessively, studied film-making under Jean Epstein, and wrote his first film reviews. After a violent break-up with Epstein, Buñuel became film editor for La Gaceta Literaria in 1927. Together with Dalí, he explored the film techniques of slow motion, dissolves, and superimpositions.

Among his most life-changing encounters of this period was with the Surrealist movement, whose founder, the poet André Breton, called for a liberation from "the absolute rationalism" that he believed had narrowed human experience since Descartes (and the later French Enlightenment). Breton argued for a new exploration of the human imagination, of the subconscious, of dream-life, madness, and even the supernatural. Influenced by Freud, Breton defined Surrealism in his first manifesto of 1924 as "pure psychic automatism" that expresses "the absence of all control exerted by reason, and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations." Surrealism was also anti-bourgeois, attacking conventional societal norms of conduct, class, and sex, as well as rejecting French colonialism and allying itself closely with communism and anarchism.

Breton was particularly fascinated by the lack of will that humans experience in dreams: "The mind of the dreaming man is fully satisfied with whatever happens to it. The agonizing question of possibility does not arise...Let yourself be led. Events will not tolerate deferment. You have no name. Everything is inestimably easy." This sense of suspended will, of impotence and passivity recurs frequently in Buñuel's films, from the disturbing image of the woman at the start of Un Chien Andalou, who passively allows her eyeball to be sliced, to Mathieu in That Obscure Object of Desire (1977), who must watch as his beloved Conchita makes love to another man.

Buñuel shared Surrealism's interest in dreams and hypnotism, later calling film itself a kind of "cinematographic hypnosis" as the dark cinema took the viewer into the unconscious. His first film collaboration with Dalí, Un Chien Andalou (1929) came directly from their dreams: Dalí dreamed of the ants emerging from a wound on his hand, Buñuel of horizontal clouds slicing the moon like a razor slicing an eye.

The Surrealists loved film for its power to shock and disorientate. Connecting himself to the Surrealist movement, Buñuel later said of this period: "It was an aggressive morality based on rejection of all existing values. We had other criteria: we exalted passion, mystification, black humor, the insult and the call of the abyss."

Despite Buñuel's hatred of the bourgeoisie, his first film was financed by his wealthy mother, and was actually successful with audiences, much to his surprise and even chagrin. His second film, L'Age d'Or (1930), was financed by an aristocratic patron, the Vicomte de Noailles. This time, however, Buñuel did succeed in causing a scandal, especially because of the film's scenes ridiculing Catholic priests and sacred Catholic rituals. Most shocking of all, perhaps, is the film's final episode, in which Jesus Christ appears as a sexual sadist. The film's last image is of a cross with female scalps nailed to it. Added to this, the film is rampant with scenes of absurd violence including a father shooting a son, sexual fetishism, and a repellent introductory documentary on scorpions.

Like Un Chien Andalou, L'Age D'Or disregards logical, linear narrative. The crowd at the premiere rioted, destroying paintings by Dalí, Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, and Man Ray. Le Figaro called the film "obscene, disgusting and tasteless." Buñuel wrote that it was "no more than a desperate impassioned call for murder." He often referred to his films as weapons, assaults, or even rape of the viewer. The aim was to shock spectators out of their complacency by revealing their primal nature. This film was banned until 1979. It also marked his final collaboration with Dalí, who disagreed with the attack on Catholicism. Their on-set disputes had grown so bad that one story had Buñuel chasing Dalí with a hammer across the set!

Following the scandal, Buñuel explored both Surrealist and political themes in his documentary Land without Bread (1932). Exploring the strange and savage land of Extremadura, in western Spain, his surreal voiceover spoke of dwarfs, hunger, poverty and incest. This accompanied unsparing images of horrific poverty, dead donkeys, and dead bodies, which contrasted with the classical music of the soundtrack.

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), Buñuel worked in the creation of propaganda films for the Republic, before leaving for the United States and working in both Hollywood and at New York's Museum of Modern Art, where he edited Nazi propaganda films, including Leni Riefenstahl's Triumph of The Will (1935). Buñuel's application for citizenship in the United States, however, was sabotaged by his former friend Dalí, who denounced him in his autobiography of 1942, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, as an atheist and communist, forcing his resignation. The Second World War saw Andre Breton, Max Ernst, and Yves Tanguy arrive in America, but Dalí had wrecked Buñuel's career and so remaining in America was impossible. Ernst later recalled that when Buñuel saw Dalí on 5th Avenue shortly afterwards, he knocked him to the ground.

Mature Period

Unable to settle permanently in the U.S., Buñuel arrived in Mexico in 1943, when Mexican cinema was flourishing. In 1949 he made El Gran Calavera, (The Grand Madcap), a screwball comedy of mistaken identity, and a box office hit. Although Buñuel's view was that realistic films lacked "the poetry, the mystery, all that completes and enlarges tangible reality", this period turned him into a professional filmmaker in the field of mainstream cinema. From 1946-1964 Buñuel made films ranging from melodramas, such as A Woman without Love (1951), to escapist fare, such as Robinson Crusoe (1954), in which he played with cinematographic techniques: "I amused myself with the montage, the constructions, the angles." Buñuel built into his films subversive, unsettling elements of violence and desire, dream sequences, fetishes and scenes of insect life. Buñuel's interest in exposing social injustice continued in his later works. He read in the newspaper of a child's body being dumped on a rubbish heap, a member of the child street-gangs who were then living in the slums of Mexico City. He set out to investigate. The result was the film Los Olvidados (1951). The opening credit starkly set the scene, stating that no character was fictional. It was a brutal portrayal of poverty, despair, cruelty, and betrayal, and even broke the "fourth wall" with an egg that is thrown directly at the camera lens (thus, the audience). The film caused outrage and was called an insult to Mexico, eliciting calls to revoke Buñuel's recently acquired Mexican citizenship, but it was championed by the Surrealists and particularly by the Mexican poet and thinker, Octavio Paz. The film won Buñuel the Best Director prize at Cannes.

Late Period

In the later period of his career, Buñuel combined his enhanced professional techniques and use of narrative with his Surrealist take on reality. All the themes of his early work recur: the critique of bourgeois morals and organized religion, hypocrisy, the blurring of dream and reality, thwarted desire, repression, and obsession. In 1960, he returned to Spain for the first time since the Civil War to make Viridiana (1961). The outcry over the themes of rape, incest, cruelty, and blasphemy included a scene that was considered by many as a blasphemous imitation of Leonardo Da Vinci's painting The Last Supper, showing a blind Christ and sinful disciples. The Spanish authorities banned it, but the film was smuggled to Cannes and won the Palme d'Or. When asked about religion, Buñuel said:" "I'm still an atheist, thank God." Buñuel's next film, The Exterminating Angel (1962), explores a surreal dinner party where guests find themselves unable to leave and try in various absurd ways try to discover meaning in a meaningless universe.

Buñuel never explained his work, but the links between sex and sin (and one could add, death) reflect a Catholic guilt not uncommon among Surrealist artists and writers, who were mostly born into the Catholic faith. In an interview in 1968, on the subject of his recurring dreams, Buñuel noted: "almost all my dreams are painful." He is variously frozen on a ledge, visited by dead parents, chased by a tiger, haunted by ghosts, caught defecating in public, fellating himself without pleasure, unable to find his penis, or unable to perform due to being watched.

The public scandal and international recognition that his films had generated had turned him from a subversive outcast to one of the world's most prestigious directors. He was in-demand by top actors and actresses such as Catherine Deneuve, who starred in the first of his three late masterpieces made in France, Belle de Jour (1967), where a respectable wife is also a prostitute. This challenge to expose the reality that underlies the surface of respectable society was matched by his next two films. In The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1973) the desire to eat is thwarted by bizarre coincidences, while in That Obscure Object of Desire (1977) it is sexual desire that is thwarted and compared to terrorism. In this film, one of the terrorist groups appears to be of a Catholic persuasion, with the absurd name of "Revolutionary Army of the Baby Jesus."

Buñuel's career is interesting in the way that he moved from creating such radical Surrealist work to more conventional mainstream films. Yet, while he moved away from narrative experimentation in his work, he continued to make innovative stylistic choices in his widely-distributed films and inject elements of Surrealist absurdity and dreams. Buñuel's films have influenced some of the giants of 20th century cinema. In a trip to Los Angeles in 1972 he met Fritz Lang, who had been his inspiration, and also Alfred Hitchcock, whose techniques and themes owed much to Buñuel and who called him "the best director in the world." He was unconcerned about his reputation and at the end of his life noted that when he died he would like his ashes thrown to the wind and his name forgotten. Buñuel claimed that in his life he had only one regret: "I hate to leave while there's so much going on. It's like quitting in the middle of a serial."

The Legacy of Luis Buñuel

Luis Buñuel created some of the most visually and emotionally shocking films of the 20th century, particularly his first two films, Un Chien Andalou and L'Age D'Or, and his Mexican film, Los Olivadados. The opening scene of Un Chien Andalou has never been surpassed for its disturbing image of calm and matter-of-fact violence; repeated viewings do not lessen its horror or power. While Germaine Dulac is often credited for creating the first Surrealist film, The Clergyman and The Seashell (1928), Buñuel's first two films embody Surrealist principles more fully in their violations of linear narrative and temporal unity, in their un-stylized absurdism, in their ferocious pillaging of societal and religious norms, and, most importantly, in their depiction of the pure automatism or passivity of the dream-state. Because dreams work in moving images rather than logocentric ideas, Buñuel made film itself a highly effective medium for Surrealism's exploration of the human subconscious.

After watching Buñuel's first two Surrealist films, movies by other directors that are said to be Surrealist, such as Hans Richter's Dreams That Money Can Buy (1947), can strike the viewer as tame, artsy, and fairly conventional. Buñuel's uncompromising view of reality, of human existence and cinema, continued beyond his Surrealist films. Los Olvidados, Viridiana, and Belle Du Jour expose society's cruelties, hypocrisies, injustices, and delusions. Buñuel's influence can be detected on numerous directors and scriptwriters, including Alfred Hitchcock, whose 1945 Spellbound contains dream sequences, a decor by Salvador Dalí (such as a man with scissors cutting eyeballs on the curtain of a gambling den), and Maya Deren, whose 1943 experimental film, Meshes of the Afternoon, is a conscious attempt to continue the explorations of Buñuel's first two Surrealist films. A great admirer of Buñuel was Japanese director Hiroshi Teshigahara. In his shocking 1962 film about an uprising of miners, Pitfall, he blends the violence and social realism of Buñuel's Los Olvidados with surreal incursions of the fantastic. Pedro Almodovar's Law of Desire (1986), as well as Julio Medem's Earth (1996), both trace their lineage to Buñuel and to That Obscure Object of Desire in particular. The blends of realism and surrealism that one finds in the films of David Lynch, or in the scripts of Charlie Kaufman, might be seen as, among other things, a continuation of Buñuel's legacy in contemporary cinema.

Influences and Connections

![Fritz Lang]() Fritz Lang

Fritz Lang![Buster Keaton]() Buster Keaton

Buster Keaton

-

![Salvador Dalí]() Salvador Dalí

Salvador Dalí -

![André Breton]() André Breton

André Breton ![Frederico Garcia Lorca]() Frederico Garcia Lorca

Frederico Garcia Lorca

![Alfred Hitchcock]() Alfred Hitchcock

Alfred Hitchcock![Pedro Almodovar]() Pedro Almodovar

Pedro Almodovar

![Gabriel Figueroa]() Gabriel Figueroa

Gabriel Figueroa

Useful Resources on Luis Buñuel

- The World of Luis Buñuel: Essays in Criticism (1978)Our PickBy Joan Mellen

- Surrealism and CinemaBy Michael Richardson

- Companion to Spanish Surrealism (2004)By Robert Havard