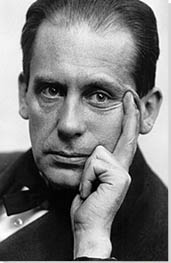

Summary of Walter Gropius

Not only was Walter Gropius one of the pioneers of modern architecture, he was the founder of the Bauhaus, a revolutionary art school in Germany. The Bauhaus replaced traditional teaching methods with a flexible artistic community, focusing on a collaborative approach to learning and the creation of integrated design projects. Later, the Bauhaus also incorporated mass production techniques into its output, designing objects and buildings for a wide audience. The school taught some of the most famous names in modernism as well as attracting established artists working within the fields. Despite its relatively short-lived existence, the Bauhaus and the design styles associated with it were hugely influential on a global scale, but particularly so in the United States where many of the artists moved before and during the Second World War to escape persecution by the Nazis.

Accomplishments

- Gropius believed that all design should be approached through a study of the problems that needed to be addressed and he consequently followed the modernist principle that functionality should dictate form. He applied these beliefs to wider social issues, designing affordable housing in the interwar period and seeking to improve physical conditions for factory workers through his architecture.

- As well as pushing boundaries in architectural design, Gropius also experimented with innovative building and assembly techniques using prefabricated units and new materials such as reinforced concrete. Similar ideas were later utilised to create cheap, mass produced housing in the 1940s (known as prefabs).

- Gropius is credited with the introduction of modernist architecture to the United States through his design of the Gropius House and his teaching at Harvard University. Gropius's buildings were in stark contrast to previous architectural styles and were characterized by their cubic design, flat roofs and expanses of glass that allowed for a merging of interior and exterior spaces.

Important Art by Walter Gropius

The Fagus Factory

Gropius designed the façade of this factory in conjunction with Adolf Meyer in the period after they left the office of Peter Behrens. The floor to ceiling glass creates a sense of light and the large rectangular panes, punctuated by steel mullions and brickwork, wrap the factory in a continuous manner rarely seen in building design before. Of particular note are the corners, where the glass joins at right angles, giving the illusion of not needing support. This works to eliminate the distinction between interior and exterior, a reoccurring theme in modernist architecture. Every element of the building is simple, functional, and cubic in construction and this pre-empts the Art Deco aesthetic of the interwar period. The entrance and clock date from a 1913 expansion to the building, also designed by Gropius and Meyer.

The building was commissioned by Carl Benscheidt, the General Manager of Fagus, a company that specialized in the manufacture of shoe lasts, foot-shaped forms that were used in the production and repair of shoes. Benscheidt was keen for the building to demonstrate a clear break with the past and this provided Gropius and Meyer with a chance to experiment with new ideas and technologies. The influence of their experience at Behrens's office, where they worked on projects such as the AEG Turbine Factory, can be seen in the openness of the aesthetic and the expansive use of glass. Gropius was particularly intrigued by how good design could benefit society as a whole and in this design he saw the use of glass as advantageous for the factory workers, who would be exposed to more light and fresh air than they had been in the enclosed brick factories of the 19th century.

Alfeld an der Leine, Lower Saxony, Germany

Sommerfeld House

Commissioned by the Berlin-based timber entrepreneur Adolf Sommerfeld as his private residence, Sommerfeld House marked the first large-scale example of the Bauhaus method of collaborative design and the unity of art forms. Almost all of the workshops of the Bauhaus Weimar contributed to the design and making of the building and its interiors with the design overseen by Gropius and Adolf Meyer. The interior featured elaborate geometric carvings by Joost Schmidt, stained glass by Josef Albers, weavings by Dörte Helm, wall paintings by Hinnerk Scheper, and furniture designed by Marcel Breuer.

Sommerfeld House is perhaps not instantly recognizable as a work by the architectural avant-garde of the period. The use of wood as the main building material lends it a traditional, rustic look and this reflects the early expressionistic phase of the Bauhaus. The plank-based design also references the owner's occupation and the building utilized a patented system of pre-cut interlocking timbers developed by Sommerfeld's own construction company called the Blockbauweise Sommerfeld (Sommerfled block building method). Despite Gropius's forward-thinking designs, he saw wood as a key material, describing it as "the building material of the present...Wood has a wonderful capability for artistic shaping and is by nature so appropriate to the primitive beginning of our newly developing life". In addition to Sommerfeld House, Gropius and Meyer were tasked with designing four houses on the same plot for employees of the Sommerfeld company. The house was destroyed in World War Two.

Berlin, Germany

Monument to the March Dead

This monument is the result of a competition launched by The Weimar Trades Unions to commemorate those who lost their lives opposing the Kapp Putsch in March 1920. This was an unsuccessful coup, led by the right-wing nationalist Wolfgang Kapp, which aimed to overthrow the Weimar government and establish a right-wing autocracy in its place. The competition committee chose Gropius's design from several submitted, and erected the monument in the Weimar central cemetery. Although Gropius maintained that the Bauhaus should not engage with politics, he agreed to participate in the competition and to involve the school's stone-carving workshop in the project. In doing so, Gropius revealed his increasingly Left leaning political sympathies. The memorial was destroyed by the Nazis due to its design and political overtones, but it was later rebuilt in the post-war period.

The design is abstract and fractured in its form and is considered part of Gropius's short Expressionist period. The lower sections form a circulatory, ascending path which visitors could follow to an enclosed area for quiet reflection. The lightning bolt rising from the main body of the monument suggests dynamism and the continued living spirit of those that died. The design bears similarities to Expressionist sculptures and architectural projects produced by Gropius's contemporaries at the Deutsche Werkbund. Its form is particularly reminiscent of the cathedral design by Lyonel Feininger which featured on the cover of the 1919 Bauhaus manifesto.

Weimar, Germany

Bauhaus building

The Bauhaus' relocation from Weimar to the industrial city of Dessau provided Gropius with a blank site on which to build a campus that embodied the principles of the school. In his choice of materials and design, Gropius developed ideas first fostered in the Fagus Factory in Saxony and the buildings all utilize new industrial materials such as reinforced concrete and are geometric in design with flat roofs. Additionally, each space was carefully designed to reflect its function. The three-story workshop wing features a glass curtain wall sitting on a steel framework, ensuring that workshops were well-lit, whilst also presenting the idea of the school as an experimental laboratory for new technologies and ways of creating. The interiors of the workshop wing were designed to be free flowing and encourage interconnectivity and movement, while large spaces had moveable partition walls for flexible learning. All the interior fixtures and fittings were designed and produced in the Bauhaus workshops, building community and encouraging collaboration between departments.

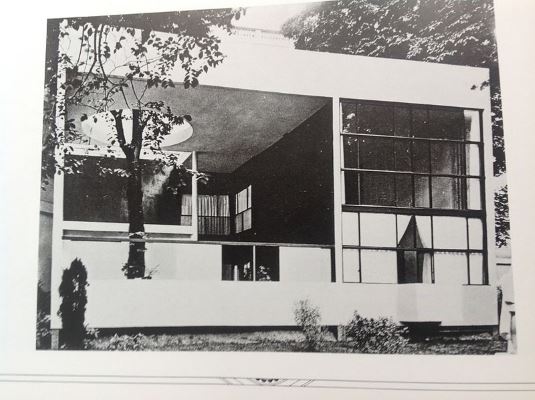

A five-storey block accommodated the students and junior masters in 28 studio flats with small cantilevered balconies. Away from the main site, Gropius designed houses for the Bauhaus Masters and their families. Originally Gropius had intended to build these using entirely prefabricated components, although, due to technical restrictions, this scheme was only partially realized. The Masters' houses are made of interlocking cubes of different heights and each one includes a studio with large windows and a balcony.

Dessau, Germany

Gropius House

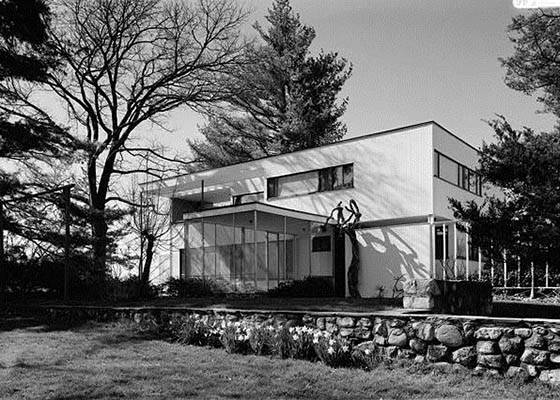

Built as his own family home shortly after emigrating to the United States, the Gropius House was highly influential in demonstrating modernist architecture outside of Europe. Gropius used materials typical of New England buildings, such as wood and brick, and combined them with industrial materials, including glass and steel. The structure is a traditional New England post-and-beam wooden frame, integrated with newer features such as the long windows on the first floor and the glass blocks in the porch. In keeping with the Bauhaus philosophy of total art, the house contained furniture designed by his contemporary Marcel Breuer, as well as works by Herbert Bayer and art by the painter and sculptor Joan Miró.

As with his earlier designs for factories and industrial buildings, Gropius planned the house to be simple and efficient and to fulfil the daily requirements of his family first and foremost. This can be seen in the links between outdoor and indoor spaces as well as practical adaptations such as the incorporation of built-in storage and a separate entrance for his adopted daughter. As well as spatial awareness within the house, Gropius divided the land around the house into multiple zones, creating a relationship between structure and site. Gropius House was the best way for the architect to establish himself and build his reputation in the United States. It served as a showcase of his ideas for his students at Harvard as well as for potential clients, demonstrating his adaptability in linking the local vernacular with cutting-edge design.

Lincoln, Massachusetts, USA

Harvard Graduate Center

The Graduate Center at Harvard University was designed by Gropius in conjunction with the younger architects that made up The Architects' Collaborative. Built to house 575 graduate students, the building complex consists of a main building, seven dormitories, a dining hall, and recreational rooms. Despite being a team effort, Gropius's influence on the project is clear. It contains features characteristic of his past buildings: the floor-to-ceiling windows give a sense of airiness and lightness to the building, as does the use of curves and pilotis (supporting columns) at ground floor level to hold up the upper storeys. The relationship between building and environment was also highly considered in the creation of inner courtyards and covered walkways connecting the individual parts of the complex. As well as glass, Gropius employed a technologically advanced steel structure filled in with limestone. Inside, Gropius's ongoing promotion of the importance of collaboration can be seen in artworks commissioned from artists including Has Arp, Josef Albers, Herbert Bayer, and Joan Miró.

Ideologically, the building brought key Bauhaus principles to an international setting: firstly, that modern architecture could benefit education, and secondly that cooperative architectural practice was valuable. It was a bold move for Harvard University, as this was, not only, the first modern building on the campus, but also the first for any major American university. Gropius commended this support of new styles, stating that: "If the college is to be the cultural breeding ground for the coming generation, its attitude should be creative, not imitative". The building can be seen as a turning point in the acceptance of International Modernism in the United States, an endorsement of The Architects' Collaborative as their first major project, and Gropius's largest public project since emigrating to the United States. It can also be seen as a fore-runner to 1950s and 60s Brutalist architecture which owed an enormous debt to the Modernist buildings of the 1930s and 40s in both style and construction.

Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

Biography of Walter Gropius

Childhood

Walter Gropius was born in Berlin to Walter Adolph Gropius, a government official and Manon Auguste Pauline Scharnweber, the daughter of the Prussian politician Georg Scharnweber. His parents were wealthy and well connected and Gropius spent his summers on the estates of landowning members of the family. Walter Gropius Senior had a keen interest in architecture and Gropius's uncle, Martin Gropius, was also an established architect, his biggest commission being the design for the Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin (1881), consequently Gropius's interest in architecture was encouraged from a young age.

Early Training

At the age of twenty, Gropius enrolled to study architecture at the Technical School in Munich and then the Konigliche Technische Hochschule in Berlin. His education was cut short when he inherited a substantial sum of money from a great aunt. Although his studies at the Hochschule were almost complete, he dropped out without taking the final exam, reflecting an early disregard for traditional methods of education.

In 1908 Gropius joined the office of the renowned architect Peter Behrens, one of the leading figures in industrial design and a creative consultant for large German industrial company AEG. Here, Gropius formed connections with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier who were based in the same office. Under the tutelage of Behrens, Gropius worked on the innovative AEG Turbine Factory and factories for the Krupp company. Working on industrial projects opened Gropius's eyes to the possibilities of new materials and construction techniques, ideas that he later applied to the design and manufacture of many buildings including mass housing projects and the Bauhaus building in Dessau.

In 1910, Gropius left Behrens's practice with fellow employee Adolf Meyer to set up their own architecture office in Berlin. The same year Gropius also began his decade-long love affair with Alma Mahler, the wife of the composer Gustav Mahler. Alma had married Mahler, 20 years her senior, in 1902, when he was director of the Vienna Court Opera, and they moved in creative circles in Vienna and, later, America. Gropius and Alma conducted a secret affair through liaisons and letters until her husband's death in 1911. They continued their intense relationship until 1913 when Gropius visited the Berlin Secession exhibition and saw Oskar Kokoschka's painting The Tempest. The painting depicts a man and woman embracing during a storm, and Gropius immediately recognized the female figure as Alma. Having discovered Alma's affair with Kokoschka, Gropius ended the relationship.

Gropius and Meyer joined the Deutsche Werkbund (German Workers' Federation); an association of designers and architects who promoted the integration of new industrial mass production with traditional art and design. During this period they designed objects such as furniture and wallpaper, as well as completing larger projects, most famously the façade of the Fagus Factory in Alfeld-an-der-Leine, Germany. This combined the modernist principle of form reflecting function with a desire to provide healthy working conditions for employees. Gropius also explored these ideas in an influential article, The Development of Industrial Buildings, published in 1913.

Their work was interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War and Gropius was drafted into the German army in August 1914. He served as a cavalry officer on the Western Front where he was wounded and received the Iron Cross for bravery. He could not forget his love for Alma and the couple reconciled, marrying in 1915 in Berlin in between Gropius's military postings. In 1916 their daughter, Manon, was born (she died in 1935). The marriage was as tumultuous as their earlier relationship and eventually ended in divorce in 1920 when Gropius discovered Alma had begun a relationship with the novelist and playwright Franz Werfel.

Mature Period

Following the war and the dissolution of his marriage, Gropius threw himself back into his architectural work. Despite previously staying out of politics, he now sympathized with the Left and became an advocate for the role that architecture and design could play in post-war social reform. In 1919 he became master of the Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstgewerbeschule (Grand Ducal Saxonian School of Arts and Crafts) in Weimar, which he renamed Staatliches Bauhaus Weimar. This was the beginning of the famous and important Bauhaus school.

Despite only being 36 when the Bauhaus opened, Gropius's reputation was already distinguished enough to attract a highly regarded faculty. The teachers came from a variety of countries and design backgrounds and included Paul Klee, Johannes Itten, Josef and Anni Albers, Herbert Bayer, László Moholy-Nagy, and Wassily Kandinsky. All were united in Gropius's aim of using workshop-based education to experiment and contribute to post-war society through art and architecture. The school's experimental approach was outlined in Gropius's 1919 founding manifesto. He wrote of all arts being equal and he consequently sought to reunite art forms that had been separated in traditional art and design schools. The teaching programme aimed to develop its students as well as provide technical skills, combining the disciplines of art, craft, and technology into a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). All students completed a preliminary course before specialising in workshops directed by a craftsman (Master of Works) and an artist (Master of Form). They studied fine arts and crafts, as well as the technology of materials and production. Collaboration was encouraged and students were taught to consider the larger context of society and environment when designing.

The mid-1920s marked a pivotal period for Gropius and the Bauhaus. In 1923, he initiated a change in the school, turning away from a craft-based, handmade output to one "adapted to our world of machines, radios and fast cars". To achieve this aim, he placed a new focus on functionable, affordable design and industrial production. The move was catalyzed by a number of incidents including the arrival of Theo van Doesburg, a Dutch artist associated with De Stijl and the constructivist El Lissitzky in Weimar, both of whom were proponents of industrial design. Most prominently, however, was the fact that in 1922 a condition of the school's renewed funding was that it start to publicly demonstrate its accomplishments. This change in direction caused a rift amongst the faculty, resulting in the resignation of the tempestuous Expressionist painter and director of the preliminary course, Johannes Itten whose mysticism and emphasis on personal artistic journeys came into conflict with Gropius's new vision. Gropius's decision to replace Itten with the Hungarian artist and designer László Moholy-Nagy further signalled the change towards a more technological curriculum. The same year also saw Gropius marry again, this time to Ise Frank - the couple remained together until his death.

In 1925, under pressure from a newly elected right-wing government in Weimar, Gropius moved the Bauhaus to the industrial city of Dessau. This created an opportunity for him to design a new school building and professors' housing complex, creating a campus that itself was a Gesamtkunstwerk. The move, however, did not save the school from increasing tensions caused by Gropius's change towards industrial design. These disagreements came to a head in 1926, when the Bauhaus found itself in financial difficulties. This prompted Gropius to ask his faculty to accept a 10% pay cut. Kandinsky and Klee refused, with the latter writing to Gropius: "I look gloomily ahead to further negotiations and am afraid of something that was avoided even during the worst phase at Weimar: an inner disruption". They eventually compromised on a 5% salary contribution. Alongside discontentment within the faculty, Gropius also had to contend with increasingly right-wing politics in Dessau and the country as a whole. He came to have strained relationships with local politicians, not aided by the lack of support from within his own school. Ultimately, in 1928, Gropius left the Bauhaus and moved to Berlin to open a private practice. He was succeeded as Bauhaus director by Hannes Meyer.

Between 1926 and 1932 Gropius worked on a number of large-scale housing projects in Berlin, Karlsruhe and Dessau. In these he sought to combat the lack of affordable housing in the inter-war period by creating cost effective pre-fabricated concrete building parts which were mass produced and assembled on site. Despite the industrial nature of the production, his housing designs focused on creating better living conditions for poorer families through the incorporation of well-equipped, light interiors and external green spaces.

Late Period

The changing political landscape in Europe during the early 1930s began to affect Gropius's career. The Gestapo closed the Bauhaus in 1933 and Gropius's designs for government projects were continuously rejected due to his Left-leaning ideas. With Nazi condemnation of modern art and architecture as 'un-German' and degenerative on the increase, those associated with the Bauhaus scattered, emigrating all over the world. In 1934, with the help of the English architect Maxwell Fry, Gropius and his family (they had adopted the young daughter of Ise's sister after her untimely death) escaped Germany for Britain, relocating to Hampstead in London. Here, he worked as part of the modernist Isokon group with other similarly-minded émigrés. During this time he designed a school in Impington, Cambridge and a house for playwright Benn Levy in London.

The Dean of Harvard's Graduate School of Design, Joseph Hudnut, visited Gropius in London in 1937 and subsequently offered him a job. Inspired by Gropius's innovative approach to arts teaching, Hudnut tasked Gropius with reorganising Harvard's traditional design curriculum. Gropius accepted and moved to the United States, along with Marcel Breuer. In 1938 Gropius was appointed Chair of the Department of Architecture and the same year he built a house for himself and his family in Lincoln, Massachusetts. Now known as Gropius House, this building was hugely influential in introducing international modernism to America.

During this time Gropius co-founded The Architects' Collaborative with a new generation of young American architects. Building upon the teamwork-based ethos Gropius had fostered at the Bauhaus, the Collaborative went on to become one of the most distinguished post-war architectural practices in the United States. In 1944 Gropius became a naturalized citizen of the United States and over the next two decades continued his architectural output, receiving numerous accolades, including election into the National Academy of Design and the AIA Gold Medal. He died in Boston, Massachusetts following a short illness in 1969.

The Legacy of Walter Gropius

Although he is remembered for championing architectural mass production techniques and as a key figure in introducing modernist architecture to the United States, Gropius's most lasting achievements were as an educator. The Bauhaus challenged and redefined the way in which art, design, and architecture was taught, moving towards a more collaborative and interdisciplinary mode of operation as well as incorporating technological innovation and mass production techniques into the syllabus. It also brought together a fascinating and hugely influential group of teachers and artists who worked alongside each other and together left a lasting legacy despite only existing for just over a decade Gropius was fundamental in shaping this approach, and in continuing its development through his teaching in the United States. This legacy was recognized during Gropius's lifetime and, along with Herbert Bayer, he co-curated Bauhaus 1919 - 1928, a retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1938.

Influences and Connections

-

![Le Corbusier]() Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier -

![Ludwig Mies van der Rohe]() Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe - Peter Behrens

- Adolf Meyer

-

![Lyonel Feininger]() Lyonel Feininger

Lyonel Feininger - Maxwell Fry

- John Harkness

- Norman Fletcher

- Jean Fletcher

-

![Marcel Breuer]() Marcel Breuer

Marcel Breuer ![Herbert Bayer]() Herbert Bayer

Herbert Bayer![Hannes Meyer]() Hannes Meyer

Hannes Meyer![Marianne Brandt]() Marianne Brandt

Marianne Brandt- Karel Teige

Useful Resources on Walter Gropius

- Walter Gropius: Visionary Founder of the BauhausOur PickBy Fiona MacCarthy

- Bauhaus: Workshops for Modernity, 1919 - 1933Our PickBy Barry Bergdoll and Leah Dickerman

- The Bauhaus Group: Six Masters of ModernismOur PickBy Nicholas Fox Weber

- Walter Gropius, 1883 - 1969: The Promoter of a New FormOur PickBy Gilbert Lupfer and Paul Sigel

- 100 Artists' Manifestos: From the Futurists to the StuckistsSelected by Alex Danchev

- BauhausBy Frank Whitford

- The Bauhaus Reassessed: Sources and Design TheoryBy Gillian Naylor

- The Bauhaus Idea and Bauhaus PoliticsBy Éva Forgács

- Modern ArchitectureBy Alan Colquhoun

- Modern Architecture: A Critical HistoryBy Kenneth Frampton