Summary of Marcel Breuer

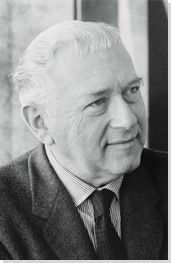

His friends and family affectionately called him Lajkó, but the rest of us know him as Marcel Breuer, the Hungarian-American designer whose career touched nearly every aspect of three-dimensional design, from tiny utensils to the biggest buildings. Breuer moved quickly at the Bauhaus from student to teacher and then ultimately the head of his own firm. Best known for his iconic chair designs, Breuer often worked in tandem with other designers, developing a thriving global practice that eventually cemented his reputation as one of the most important architects of the modern age. Always the innovator, Breuer was eager to both test the newest advances in technology and to break with conventional forms, often with startling results.

Accomplishments

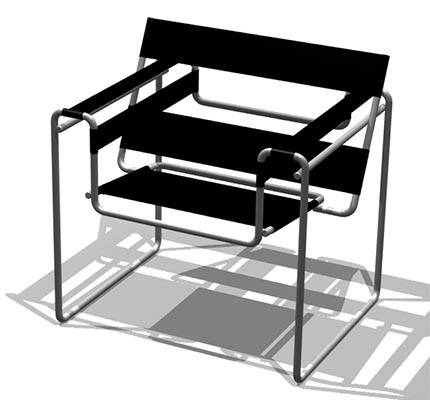

- Breuer's Wassily Chair (1927-28) became an instant classic of modern design, and even today it remains one of the most recognizable examples of Bauhaus design. For this chair, he used the newest innovations in bending tubular steel for the entirety of the structural frame, thereby demonstrating the possibilities of modern industry applied to everyday objects.

- Breuer's early success in education often overshadows his brilliant career as an architect. Although Breuer assumed the role of primary designer for some of his most famous buildings, on several others he was happy to work alongside other giants in the profession, often generously sharing credit with his collaborators - a sharp contrast with many other high-profile architects in the postwar era.

- A pioneer of the International Style in his use of steel and glass, Breuer's affinity for concrete later made him a key figure in the emergence of Brutalism, which has drawn criticism due to his designs' heavy-handed massiveness. However, Breuer counterbalanced this tendency in his small-scale houses that are notable for their sensitive handling of traditional materials, such as wood and brick.

- Breuer is one of the most important and best-known figures associated with the Bauhaus, where he was first a student and later led the furniture design workshop. His reputation as a teacher was further cemented when he joined Walter Gropius at Harvard University, teaching some of the most successful architects of the postwar era, including I. M. Pei and Philip Johnson .

Important Art by Marcel Breuer

Club chair (model B3)

Made of leather and cantilevered steel, the Wassily chair has become one of the world's most enduring and iconic pieces of furniture. Breuer designed the chair at the age of the 23, while still an apprentice at the famed Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany. Inspired by the Constructivist principles of the De Stijl movement and the frame of a bicycle, the Wassily chair distills the type to its bare essentials, reflecting the Bauhaus' proclivity for functionality and simplicity. Breuer viewed the bicycle as an object that represented the paragon of design, owing in part to the fact that its form had remained largely unchanged since its inception. The tubular steel of the bicycle's handlebars also intrigued Breuer, as it was light, durable, and suitable for mass production (a manufacturer by the name Mannesman had recently perfected a type of seamless steel tubing that was capable of being bent without collapsing). Breuer once mused to a friend regarding the bicycle, "Did you ever see how they make those parts? How they bend those handlebars? You would be interested because they bend those steel tubes like macaroni." Breuer bent the steel components so that they were devoid of any weld points and could thus be chromed piecemeal and assembled. He named the chair after the painter Wassily Kandinsky, a professor at the Bauhaus, who was so enamored by the piece during a visit to Breuer's studio that Breuer fashioned a duplicate for Kandinsky's home. First mass-produced by Thonet, the license for manufacturing the chair was picked up after World War II by the Italian firm Gavina, which was in turn bought out by the American company Knoll in 1968. Knoll retains the design trademark and the chair remains in production today.

28 1/4 x 30 3/4 x 28" (71.8 x 78.1 x 71.1 cm)

Cesca Chair

Shortly after finishing his design for the "Wassily" chair, Breuer continued his explorations of the plastic possibilities of tubular steel with the B32, or The Cesca Chair, as it is now popularly called. In this case, he molded the material into a single, snaking outline onto which he attached two beechwood frames covered in caning. The form of the frame - where the seat and back are supported only by the legs at the front - comprises the first cantilevered chair design in history, a feat only possible due to the seamless steel tubing that resists collapsing when bent. With ease, Breuer's design thus marries the traditional methods of craftsmanship - the woven caning hand-sewn into the wood frame - with the industrially mass-produced tubular steel. The chair takes its popular name from that of Breuer's daughter Francesca; the moniker was suggested by the Italian furniture manufacturer Dino Gavina, whose firm started making the Cesca (and the B3 Wassily chair) with Breuer's permission in the 1950s before being bought out by Knoll in 1968.

Imitations of the chair are ubiquitous, with only slight subtleties - such as the distinctive patina of the beech, the curvature of the back, or the texture of the caning - differentiating knockoffs from the 1928 originals. As Elaine Louie wrote in the New York Times, the chair "costs $45 at The Door Store, $59 at The Workbench, $312 at Pallazetti or $813 at the Knoll store itself, and yet, to the average person, all the chairs look the same." Despite the iconic stature of the original design, Breuer himself made several modifications to the Cesca in later years, including choosing a shallower curve for the back and strengthening the beechwood frame by manufacturing it from two pieces instead of one. Since the Cesca's introduction, literally millions of versions have been sold to decorate homes and office buildings around the world, making it arguably Breuer's most popular chair.

Cane, Beechwood and Chromed Steel - 23.5 x 23.5 x 31 in.

John Hagerty House (aka the Josephine Hagerty House)

Erected in 1938, on the Atlantic shores of Cohasset, Massachusetts, The Hagerty House represents the first commissioned architectural collaboration between Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer (they had previously worked together on Breuer's own Lincoln, Massachusetts home), and one of the first examples of International-Style architecture in the USA. The rectilinear structure uses an L-shaped plan, with the one-story longitudinal section running north to south and parallel to the coastline. The east side of the home features floor-to-ceiling windows intended to maximize the residents' views of the Atlantic Ocean, thereby blurring the distinction between interior and exterior space. In the words of John Hagerty, "The house was to be focused like a camera toward the magnificent expanse of ocean...blank walls would cut out the view of neighboring houses." The base and south wall, constructed from the site's granite, disclose their sensitivity to the rocky environment. The house thus appears as a prism partially nestled into and partially resting on top of the shoreline, creating a kind of belvedere for the ocean views.

With its exterior staircases forged from galvanized steel pipes, terracotta chimneys, and exposed radiators, the building reflects the architects' affinity for the preponderance of utilitarian building materials in the United States. Its austere, white wood siding and extreme reliance on rectilinearity - even in the design of the base and rocky south wall - and tubular steel railings tie it both to a precise, machine-cut aesthetic associated with prodigious American manufacturing and the power of man to reshape and control nature, even as nature itself weathers and batters the structure's exterior. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Hagerty House's radical departure from traditional aesthetics was unsettling to those who enjoyed the architectural conformity of the area's large collection of Federalist and Greek Revival homes. In response to the new minimalist intrusion, one of the Hagerty's neighbors jested that it looked like "the ladies' wing at Alcatraz."

But overall, the house rapidly became a preferred destination for students, tourists, and architects due to its pioneering stature in American modern architecture. Fully cognizant of this, during their tenure as owners the Hagertys generously welcomed visitors and even offered tours to inquisitive passersby.

Cohasset, Massachusetts

Alan I W Frank House

Designed by Breuer and his partner, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, for Pittsburgh engineer and industrialist Robert Frank and his wife Cecelia in 1939-40, this is a palatial private residence encompassing 17,000 square feet over four levels of living space. Set on a sloping double plot in the fashionable Shadyside neighborhood, the house includes nine bedrooms, thirteen bathrooms, five terraces, an indoor swimming pool, and a rooftop dance floor. The general oblong prismatic form is punctuated on the main facade by two projecting balconies, one of which forms the roof of the main entrance. To the right of the entry, the Frank house's signature aspect, a cantilevered sweeping staircase that connects the various levels - rises dramatically behind a three-story curved window.

The massive size of the residence and the Franks' deep pockets afforded Breuer and Gropius a wide berth of freedom of imagination in their designs, making the house a modern Gesamtkunstwerk, or "total work of art." The success of the house lies in its continuous interplay between opposites: rigid geometries and sensuous curves, theatricality and drama counterbalanced by spaces of intimate scale and the use of man-made technologies alongside a sensitivity to the outdoors through the use of natural materials such as stone and wood. The relationship between client and architects was no less important, as Robert Frank frequently corresponded with Breuer and Gropius on the house in letters stretching for several pages, pushing them to incorporate innovations into the house not commonly seen elsewhere, such as a method of using heat removed by the air-conditioning system to warm the indoor pool. The result was a building whose construction has withstood the test of time remarkably.

The notion of a "total work of art" extended to literally every aspect of the design, with the emphasis on innovation seen in the hundreds of pieces of furniture and decor designed by Breuer using the most cutting-edge materials - new resins, for example, and Lucite, which had only been developed in the 1920s. These aspects dovetailed with the Franks' active involvement with and hosting of events for the Pittsburgh arts, cultural, and educational communities. As a commitment to the house as an artwork itself, the Franks' son, Alan I W Frank (who still occupies the house) has preserved virtually all of the residence's original furnishings and created a foundation to care for it as a living museum of the architects', and clients', vision.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

The Whitney Museum of American Art

Composed of granite-covered concrete, the Met Breuer (formerly the home of The Whitney Museum of American Art) has often been described as resembling an inverted ziggurat - a rectangular stepped pyramid that was sometimes capped with a temple in ancient Mesopotamia. The recess created under the main facade draws visitors inside, then allows for exhibitions to unfold with progressively larger display spaces as one ascends to the upper floors, a procession that logically terminates in the museum bookstore and café on the fifth level. The museum's blind facades, pierced at only a few points by angled, projecting windows, direct the building's focus inward, towards the art it houses. Located on the corner of Madison Avenue and 5th street on Manhattan's Upper East Side, Breuer's structure constituted a radical, jarring departure from the older, ornate surrounding brownstone, limestone and brick townhouses in terms of style, scale, and materials, provoking a round of criticism.

There were many, however, who lauded Breuer's bold statement as a rebuttal to the ubiquitous glass-and-steel towers of the International Style that, over the previous decade, had become closely identified with American corporate culture, as exemplified by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Seagram Building and Skidmore, Owings and Merrill's Lever House located on nearby Park Avenue. Breuer thus joined the ranks of many architects of the 1960s and '70s who created a new kind of monolithic monumentality, often using the massive concrete forms of Brutalism, to critique the International Style's overwhelming popularity. The inverted ziggurat form of the Whitney Museum subtly recalls the screwlike design of Frank Lloyd Wright's inward-looking Guggenheim Museum, completed just a dozen blocks to the north.

Along with Wright's building, and the host of other major museums nearby, the MET Breuer further serves to cement the Upper East Side as an artistic enclave. As August Heckscher once observed, "A whole section of the town has been pinned down by this structure; the galleries and small shops around it fall into place and have their meaning drawn out and expressed in its bold form." Breuer's building thus at once questions the prevailing norms of modern architecture and yet provides an anchor for the surrounding urban fabric.

New York, New York

St. Francis de Sales Catholic Church

Located just south of Muskegon, on the eastern edge of Lake Michigan, Saint Francis de Sales Catholic Church sits amidst a mixture of single-family homes and commercial and industrial structures. Breuer constructed the edifice out of concrete and steel, using a decidedly sculptural set of forms; in all, a hallmark of the Brutalist designs of his late career. The inclined main facade of the church, or "banner" as it is sometimes called, develops from a rudimentary trapezoidal design, narrow at its base and broadening to the roofline seventy-five feet above ground, where the church's bells are suspended from a projecting cantilever. The exterior appears smooth from a distance, but upon close inspection reveals the delicate grain of the wooden molds for the concrete, the subtle striations of which are echoed and exaggerated in the ribbed pattern of the hyperbolic paraboloid exterior walls. A cantilevered balcony creates a low ceiling above the main entrance around the other end of the church, producing a dramatic effect when the visitor emerges into the soaring height of the sanctuary proper. Here, the inclined, windowless concrete walls give the effect of a cave-like, yet warm, communal space, at once welcoming and enfolding those inside.

Breuer's design for St. Francis de Sales represents just one example of his exploration of new possibilities for religious architecture. The decidedly cold and utilitarian material of concrete connects with both a sense of artistic minimalism as well as an asceticism devoid of expensive ornament, similar to the vow of poverty and simplicity the Catholic Church imposes upon its clergy, and in contrast to the exuberant sculpture traditionally associated with Catholic sanctuaries. The form of the church - with the main slab of the facade resting against two concave flanking walls tapering to the ground - seems to mimic the shape of a bird with wings extended, rising above the rough-hewn base resembling the fortified walls of a bastion. It suggests the abstracted form of a dove, symbolizing peace, above the castle-like base, perhaps a subtle reference to a church as a place of spiritual refuge. The soaring height of the sanctuary, accentuated by the inclined walls and the vertical ribs of concrete, conveys a sense of spirituality, yet also imparts a sense of humility in worshippers as it dwarfs them through its dramatic scale.

Norton Shores, Michigan

UNESCO Headquarters, Main Building

One of Breuer's most prominent architectural commissions was the headquarters for UNESCO, which he designed in collaboration with Bernard Zehrfuss and Pier Luigi Nervi. The selection of the three was not without controversy, as Le Corbusier coveted the job for himself, but ultimately agreed to serve as part of a five-member consulting team that also included Walter Gropius, Sven Markelius, Ernesto Rogers, and Lucio Costa. The property, still owned by the French state, occupies a prestigious location in the seventh arrondissement of Paris adjacent to the École Militaire. Breuer and his collaborators' design for the structure consists of a Y-shaped plan (often called a "three-pointed star"), mounted on seventy-two massive reinforced concrete piloti, and facades distinguished by their staggered levels of elongated uniform windows. Offset slightly from the center of the Y on the main facade is a concrete hood that welcomes visitors into the service core like a giant half-funnel. Today, the site contains several other significant auxiliary structures (some designed by Zehrfuss alone), but Breuer, Zehrfuss and Nervi's edifice remains the linchpin of the complex.

The UNESCO headquarters' piloti, construction in steel, concrete, and glass - especially its window-filled facades - firmly establish it within the clutches of the International Style. But this association is tempered by the dramatic concave sweep of the building's three wings (or three facades), which, in forming the three-pointed star, provide a sculptural counterpoint to the rigidity of modernism. The sweep of the wings themselves in different directions suggests the ways in which UNESCO reaches to and seeks to bring cultural understanding and education to the far-flung corners of the globe. The choice of Breuer - a Hungarian-born designer who had lived and worked in Germany and (by this time) the USA - as one of an international group of three architects is significant precisely because of his own preference for collaboration (and shared credit) with others in the design process. This, in combination with UNESCO's decision to commission several high-profile international artists - Alexander Calder, Joan Miro, Pablo Picasso, Henry Moore, Isamu Noguchi, among others - to adorn the building and grounds with their own site-specific works underscores the institution's commitment to worldwide cooperation and physically marks the site as an important center for research, promotion of cultural events, and the funding of educational programs and projects.

Paris

Biography of Marcel Breuer

Childhood and Education

Marcel Breuer was born on May 21, 1902, in Pécs, Hungary, a small town near the Danube River. After graduating from high school at the Magyar Királyi Föreáliskola in Pecs, Breuer enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna to study painting, where he had been offered a scholarship. He almost immediately disliked the program, however, and within weeks of joining, he left to begin an apprenticeship with a Viennese architect. Breuer was eager to work with his hands and joined the cabinetmaking studio of the architect's brother. At age 18, in 1921, he moved to Weimar, Germany, to enroll at a new school called the Bauhaus, founded in 1919 with a mission to marry functional design with the principles of fine art. Its head, the architect Walter Gropius, immediately recognized Breuer's talent and promoted him within a year to the head of the carpentry shop. At the Bauhaus, Breuer produced the furniture for Gropius' Sommerfeld House in Berlin as well as his acclaimed series of "African" and "Slatted" chairs. But he also became acquainted with many of the most important artists of this era, who likewise worked and taught at the Bauhaus, including Wassily Kandinsky, László Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, and Josef Albers. Breuer later reflected that Klee served as one of his two greatest teachers in life, along with his high school geometry instructor.

In 1924, he finished his studies at the Bauhaus and briefly relocated to Paris before returning to the Bauhaus after it moved to Dessau in 1925. During the late 1920s and early 1930s, Breuer supported himself largely from fees garnered from his furniture designs, most notably the widely reproduced "Wassily" chair, as his architectural commissions were few and far between at this stage in his career. In 1926, Breuer married fellow Bauhaus graduate Marta Erps. While his parents were both Jewish, Breuer was forced to officially renounce his faith in order to marry Erps, due to the anti-Semitic hostilities in Germany at the time.

Mature Work

In 1928, Breuer moved to Berlin, to begin his own architectural practice; in 1934, he designed the Doldertal Apartments for the well-known Swiss architectural historian Sigfried Giedion in Zurich. Breuer moved to London in 1936, at the behest of Walter Gropius, who was concerned for his safety during the Nazi occupation. Here, he found work with Jack Pritchard of the Isokon Company, one of the earliest champions of modern design in Britain, where he designed the "Long" chair predominantly from plywood. The following year, Breuer left Europe permanently to join Gropius in teaching architecture at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts; many of their students would themselves go on to become legends in the field, such as I.M. Pei, Paul Rudolph, and Philip Johnson. From 1938 to 1941 Breuer and Gropius collaborated on various architectural projects throughout the northeastern United States, including each of the architects' own houses as well as the Pennsylvania state exhibition at the 1939 World's Fair in New York.

Breuer finally moved to New York City in 1946, where he would work for the remainder of his life, and continued the collaborative efforts that had marked much of his career, mostly with Hamilton Smith. Over the next thirty-five years his practice expanded considerably; although he had worked mostly on small-scale domestic structures before the war, Breuer increasingly took on larger and more diverse institutional projects. He sought and regularly received internationally-renowned commissions, including the Sarah Lawrence College Theatre in Bronxville, New York (1952); St. John's Abbey and University, Collegeville, Minnesota (1953-61); the De Bijenkorf department store, Rotterdam (1955-57); the headquarters for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Washington, D.C. (1963-68); and the Atlanta Central Library (1969-80). He retired in 1976, the same year that he was awarded the Grande Medaille d'Or by the French Academie of Architecture.

The Legacy of Marcel Breuer

Today, Marcel Breuer is regarded as one of the most important modernists in architecture and design. His furniture productions remain as influential and popular today as ever before, and continue to be mass-produced by esteemed manufacturers such as the Knoll Group. Breuer's most famous chair, the "Wassily," in the words of New York Times journalist Maura Egan, is a manifestation of "modernism's faith in technology, convenience, and the promise of a better life." Breuer's continual interest in the possibilities of new materials and technologies and the reexamination of trends in architectural practice also mark him as an important practitioner of modernist theory. Although he eventually abandoned teaching in favor of his own practice, Breuer also left an important legacy as an instructor, both at the Bauhaus and eventually also at Harvard, where he and Gropius introduced the International Style on a large scale to American students and architects for the first time.

Influences and Connections

![Modern Architecture]() Modern Architecture

Modern Architecture

Useful Resources on Marcel Breuer

- Marcel Breuer and a Committee of Twelve Plan a Church: A Monastic MemoirBy Hilary Thimmesh

- Marcel Breuer: A MemoirOur PickBy I.M. Pei and Robert Gatje

![Paul Klee: Affected Place [<i>Betroffener Ort</i>] (1922)](/images20/works/klee_paul_3.jpg?1)