Summary of László Moholy-Nagy

László Moholy-Nagy is arguably one of the greatest influences on post-war art education in the United States. A modernist and a restless experimentalist from the outset, the Hungarian-born artist was shaped by Dadaism, Suprematism, Constructivism, and debates about photography. When Walter Gropius invited him to teach at the Bauhaus, in Dessau, Germany, he took over the school's crucial preliminary course, and gave it a more practical, experimental, and technological bent. He later delved into various fields, from commercial design to theater set design, and also made films and worked as a magazine art director. But his greatest legacy was the version of Bauhaus teaching he brought to the United States, where he established the highly influential Institute of Design in Chicago.

Accomplishments

- Moholy-Nagy believed that humanity could only defeat the fracturing experience of modernity - only feel whole again - if it harnessed the potential of new technologies. Artists should transform into designers, and through specialization and experimentation find the means to answer humanity's needs.

- His interest in photography encouraged his belief that artists' understanding of vision had to specialize and modernize. Artists used to be dependent on the tools of perspective drawing, but with the advent of the camera they had to learn to see again. They had to renounce the classical training of previous centuries, which encouraged them to think about the history of art and to reproduce old formulas and experiment with vision, thus stretching human capacity to new tasks.

- Moholy-Nagy's interest in qualities of space, time, and light endured throughout his career and transcended the very different media he employed. Whether he was painting or creating "photograms" (photographs made without the use of a camera or negative) or crafting sculptures made of transparent Plexiglass, he was ultimately interested in studying how all these basic elements interact.

Important Art by László Moholy-Nagy

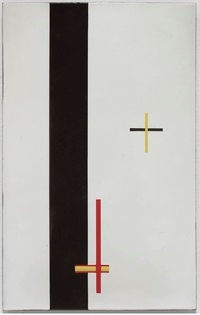

Konstruktion in Emaille 1 (Construction in Enamel 1, also known as Telephone Painting)

in this abstract geometric composition, a thick black vertical bar intersects against a bare white background, while in front of it in the lower center, a small yellow horizontal rectangle, outlined in red, sits behind a further, thin red vertical. In the upper right third of the painting, a second cross shape, formed from intersecting black and yellow stripes, seems to levitate in the space behind the central black girder, creating a subtle sense of depth. Due to the quality of movement which the painting generates, the distant shape almost seems to approach the viewer, while at the same time, the painting conveys a sense of minimalistic, architectonic order apposite to contemporaneous architectural styles.

In 1923, Moholy-Nagy identified this painting with Constructivism, which had emerged in Russia in the 1910s but was at that time sweeping westwards, partly through the activities of the Bauhaus, seen as Constructivism's most significant outpost in Norther Europe, and where Moholy-Nagy had been appointed as preliminary course director in the year of the work's completion.

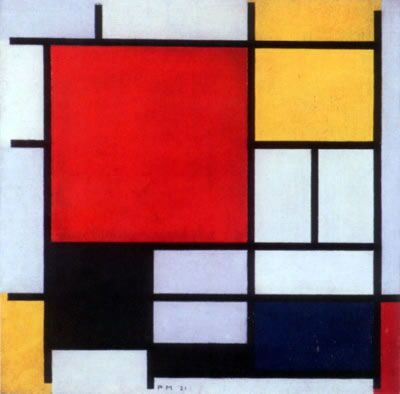

The piece also bears an obvious affinity to the contemporaneous Dutch movement of De Stijl particularly in the use of minimal geometrical arrangements and primary colors. As art historian Leah Dickerman puts it, Moholy-Nagy's painting during this period served as "both manifesto and testing ground for a Constructivist and de Stijl vocabulary." The work is radically innovative both in terms of choice of materials - porcelain enamel on sheet metal - and in terms of its process of construction. Using a color-chart produced for advertising and sales by a commercial sign factory, Moholy-Nagy phoned in the instructions for the painting's composition to the factory foreman, working from a diagrammatic grid to determine where shapes would appear on the "canvas". Moholy-Nagy described the process as akin to "playing chess by correspondence." As the curator Oliver A. I. Botar states, "to reject this belief in the sign or trace of the hand, Handarbeit, as a signifier of authenticity was a truly radical move." The artist made five such Telephone Paintings, and this one was produced in three different sizes, a process which reflected Moholy-Nagy's interest in "seriality"; he envisioned people ordering the works directly, in whatever size they wanted.

Rejecting the "aura of the art object" in favor of a process of industrial design, undertaken by an anonymous third party, Moholy-Nagy predicted Walter Benjamin musings on art's loss of spiritual resonance in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1936). The telephone paintings also prefigure a whole range of later developments in modern art, including Andy Warhol's factory-produced screen-prints, the serial works of Minimalists, and the outsourced composition processes of the Conceptual Artists. In visual terms, Moholy-Nagy's influence can be sensed in Peter Halley's Neo-Geo paintings, such as Red Cell with Conduit (1962), which depict geometric forms in primary colors intersecting at right angles.

Porcelain enamel on steel - Guggenheim Museum, New York

Pneumatik (Tire)

In this playful collage-work from 1923-24, a motor-car races along a curved road constructed from the word "pneumatik," a reference to a new type of air-pressurized tire. Due to the use of vanishing-point perspective, the letters grow larger as if the car were racing towards the viewer, the front P intersecting with a white curve which surges upwards through the pictorial plane, creating a dynamic sense of movement.

This work is an example of what Moholy-Nagy called his "Typophotos", which combine typography and photo collage: type is transformed into a component of visual communication, rather than being used solely for its semantic content. Forms of visual poetry and letter-based collage had been pioneered by artists such as the Futurists since the early 1910s, and graphically adventurous use of type was also abounding in the new advertising culture of the twenties, but never had lettering and photography been combined in this way. Nonetheless, we can sense Moholy-Nagy's creative antecedents in this work: in the Marinetti-esque speeding motor-car on the one hand, and in the Typophoto's explicit commercial function on the other. The artist himself described the Typophoto as "communication composed in type", adding that while "[p]hotography is the visual presentation of what can be optically apprehended", "[t]ypophoto is the visually most exact rendering of communication." He saw Pneumatik as a key example of the genre, which expressed "the new tempo of the new visual literature".

In hindsight, we can see that Moholy-Nagy's Typophotos preempt the visually adventurous uses of language made both by subsequent commercial designers and by later avant-garde art and poetry movements. As well as predicting later developments like the Concrete Poetry movement of the 1950s-60s, we can sense the influence of Moholy-Nagy's 1920s graphics on modern designers such as Neville Brody, Peter Saville and David Carson.

Collage - Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humblebaek, Denmark

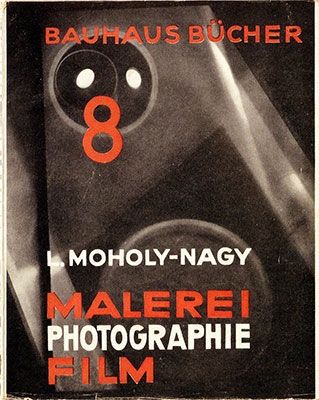

Malerei Photographie Film (Painting Photography and Film)

Moholy-Nagy was responsible for the typography and graphic design of all but three instalments of the Bauhaus Bücher ("Bauhaus Books") series, issued through the publishing arm of the Bauhaus. This image shows the cover of his own book Malerei Photographie Film ("Painting Photography and Film") (1925), the eighth volume in the series. It is considered a landmark work, showcasing Moholy-Nagy's pioneering achievements across all three media; the front cover is a photographic study featuring various geometric shapes outlined in white, with boldly ruled sans-serif letters in red and white. To the left and right, diagonal planes of light materialize, suggesting the photographic trace of an object, in the style of Moholy-Nagy's "photograms". The design continues onto the back of the book, as the left diagonal reveals itself to be a strip of film. For the artist, the book-cover represented a unique design opportunity, a kind of double-sided picture plane, on which the spirit of the book's themes and contents could be materialized, thus making the cover a crucial creative element of the work in the spirit of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art.

Moholy-Nagy played a leading role in launching the Bauhaus Bücher series in 1924; it would go on to publish an iconic and canonical range of artists' books. His pioneering designs for the series radically transformed thinking around book publishing, which he had previously criticized for its "monotonous grey" linearity. By contrast, Moholy-Nagy pioneered stylistically unified branding, with element of the book, from typography to layout to cover designs and binding, contributing to the overall creative effect. Key to this approach was Moholy-Nagy's emphasis upon the "typographical process", which he described in 1925 as "based on the effectiveness of visual relationships. Every age has its own visual forms and, accordingly, its own typography; and the latter, being a visual form, has to take account of the complex psycho-physical effects upon our organ of vision; the eye."

Such ideas, and the typographic designs that they spawned, were a fundamental influence on Jan Tschichold's Die Neue Typographie ("The New Typography") (1928), a book that became a bible for practicing graphic designers during the modernist era. Moholy-Nagy's book and lettering designs also influenced Gyorgy Kepes, his assistant during the late 1920s, who later founded the Center for Advanced Visual Studies, promoting collaboration between the arts and sciences, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Moholy-Nagy's ideas have also played a notable role in guiding the course digital design, influencing contemporary software designers such as Ben Fry, Casey Reas, and John Maeda.

Letterpress printed book - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Photogram

This famous early Photogram shows the reverse-silhouette of the artist's hand, intersected by a long rectangular grid of white lines and overlaid with the shape of a paintbrush, across which a further ghostly set of digits is embossed. Moholy-Nagy was engrossed with the life and form-giving effects of light throughout his career, and nowhere is that obsession more clear than in his photograms, in which light is the very means of visual composition: "the medium of plastic expression", as he put it. As the art historian Leah Dickerman notes, however, the photogram also represents the "trace of physical contact," thus having a strongly tactile quality also and slyly suggesting that the "artist's touch" could be as significant to the new medium of photography as it was for painting.

Photograms were camera-less photographs, created by exposing photosensitive paper to light in controlled conditions, with objects placed over the 'canvas' to leave white patches unaltered by the darkening effects of ray on page. The technique had been pioneered by Henry Fox Talbot in the early-to-mid nineteenth century, and Moholy-Nagy also found immediate precedents in the Schadographs and Rayographs of his Dadaist contemporaries Christian Schad and Man Ray. But Moholy-Nagy's Photograms represent a more concerted, considered use of the medium, backed up not by a Dadaist desire to break down medium-boundaries, but by an earnest belief in the life and art-enhancing possibilities of photography.

Moholy-Nagy used images of hands in a number of his Photograms: they take on a quality which is at once archetypal and anonymous, and yet infused with a sense of personal and bodily agency; the fact that the artist's left thumb was shattered by shrapnel during his service in World War One grants a sense of defiance to the motif of creative power. Throughout his career, he continued to return to the Photogram as an enduring medium of expression, and his wife, the artist Lucia Schulz, who had studied philosophy and art history and was also a gifted photographer, also began experimenting with photograms in 1922. At the School of Design in Chicago, which Moholy-Nagy founded in 1939, courses in the "light laboratory" were a core element of the program, with many students creating photograms in the style of their teacher. Moholy-Nagy's photograms influenced subsequent artists including Arthur Siegel, who studied with him, and, more recently, Thomas Ruff.

Gelatin silver print - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

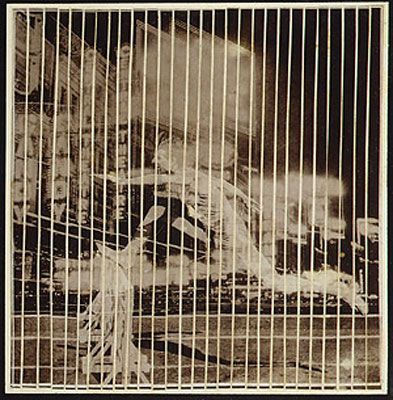

Puppen, Ascona (Dolls, Ascona)

This uncharacteristically macabre image shows two dolls from an aerial perspective, lying on a white piece of cloth on a sunlit concrete balcony. The balcony's wooden screen diagonally transverses the upper left corner, casting a harsh grid of shadows across the balcony and the dolls. The doll on the left turns with an animated expression toward the other doll that lies, legless, with its eyes closed and head back, as if injured. The aerial perspective and nod to Constructivist compositional grid through the use of shadow-play create a jarring contrast with the connotations of violence and internment, which seem to refer with biographical pointedness to the horrors of World War One, a conflict in which Moholy-Nagy had served bravely.

Moholy-Nagy took this photograph while on vacation with Oskar Schlemmer, an artist and fellow Bauhaus instructor, at Casa Fantoni in Ascona, Switzerland. Moholy-Nagy, though he preferred to concentrate on his Photograms and on images of architecture, explored a surprisingly wide variety of photographical styles, and always held that it was the true medium of the twentieth century: "[i]t is not the person ignorant of writing but the one ignorant of photography", he asserted, "who will be the illiterate of the future." This particular image shows the influence of Straight Photography in its use of harsh contrast, dramatic shadow play and straight clean lines, but the limbless, lifeless, yet anthropomorphic protagonist pushes it into the uncanny world of Surrealism. Publishing the photograph in the second edition of Painting, Photography and Film in 1927, Moholy-Nagy included the following caption: "[t]he organization of the light and shade, the criss-crossing of the shadows removes the toy into the realm of the fantastic."

As Karole Vail, curator of the Guggenheim's Moholy-Nagy: Future Present exhibition in 2016 stated, the artist "believed you could use radical and unexpected angles to foster new perceptions of the world." In this sense, this image is a quintessential example of his exploration of the craft of photography.

Gelatin Silver Print - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

A 19

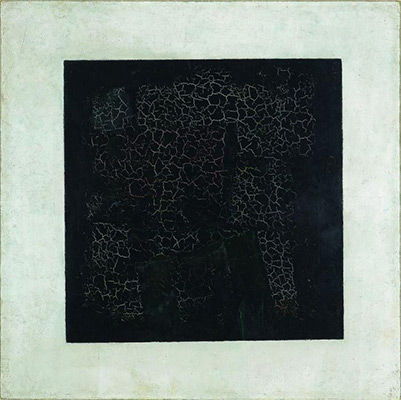

Moholy-Nagy's first abstract paintings features opaque geometric shapes reminiscent of the works of El Lissitzky and Kazimir Malevich, yet A 19 shows him evolving a unique idiom that emphasizes translucency over solidity, foregoing the iconic geometrical shapes favored by those artists. As he said, he preferred painting "not with colors, but with light." The cross motif that appears in his early oil and graphite works - an obvious nod to Malevich's Suprematism - is here enlarged and doubled, and the red and black crossbeams, overlapping each other with varying levels of transparency, create a sense of dynamic movement, with their various diagonals and triangles. The white circle, revealing the colors of the crossbeams beneath it, evokes a kind of photogram effect, as it intersects asymmetrically with columns behind it.

Moholy-Nagy had mixed feelings about painting as a medium, sensing that the notion of individual creativity that it represented was being superseded in the machine age, and that the creative spirit needed to find a new way of interacting with and accepting the mechanical and the robotic in their work. Yet he remained engaged with developments in "fine art" going on around him, including the advent of Constructivism and De Stijl by the early 1920s.

At the same time, the work shows a more overarching interest in the life-giving effects of light. As the art critic James Wilkes notes, the "beautifully modulated tones of an iconic painting such as A 19 are clearly a result of Moholy-Nagy's deepening interest in light...by 1923 he thought of light as a 'new plastic medium', analogous to 'color in painting and tone in music'." The title's combination of letters and numbers reflects the artist's belief, also dating from the early 1920s, that titles should suggest an objective order, analogous to a scientific formula. As he later wrote, he was interested in art's "primordial, basic elements, the ABC of expression itself."

Oil and graphite on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

Massenpsychose (Mass Psychosis)

This Dada-inspired collage consists of figures cut from magazines clustered in three tubular shapes that seem to resemble test tubes. To the lower left of the image, appearing closest to the viewer, a group of tribal African men form a ring, their arms linked as they squat upon the ground. A woman crouches on the upper rim of the circle, aiming a rifle towards an anatomical diagram of a man, a trilby perched absurdly on his head. Above him, a second man aims a billiard cue at a group of women in negligees, while in the background a German army officer stands erect in an empty circle. The overall effect is disconcerting, suggesting a series of absurd, arbitrary and potentially violent interactions between a disparate range of individuals, all of whom seem simultaneously isolated, and at the merges of forces beyond their control.

Moholy-Nagy felt that that photomontage - what he called the "Photoplastic" - was capable of portraying "concentrated situations", creating sets of pithy inter-associations and metaphors that could be immediately and instinctively apprehended. In this case, the connotations of the test tube, and the range of social, ethnic, and cultural types represented by the cut-out figures, suggests an analogy between social unrest and violent chemical reaction, while the rifle and billiard cue, both poised to strike, imply some imminent eruption or flashpoint. The effect is similar to that of contemporary photomontage work by Dadaists such as Hannah Höch and John Heartfield.

Like much of Heartfield and Höch's work, this Photoplastic, also known as In the Name of the Law, refers to a specific political event. In July 1927, there were massive protests in Vienna against the acquittal of a group of right-wing agitators accused of having killed two innocent bystanders - one of them a child, the other a war veteran - during a street skirmish earlier in the year. Protestors occupied the Austrian Parliament and set fire to the Palace of Justice; in response, the police opened fire on the crowd, killing 89 demonstrators. Thus, as the art historian Stefan Jonsson has noted, the artist is offering an acerbic evocation of the volatile excesses of group psychology, "referencing, with tongue in cheek, Freud's book Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1921)".

Photo-montage - George Eastman House, Rochester, New York

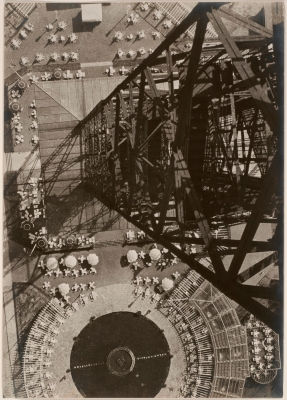

Funkturm Berlin (Berlin Radio Tower)

Taken from the top of the Berlin Radio Tower - a "purposefully disorienting vantage point", as the art historian Christopher Phillips puts it - Moholy-Nagy's famous 1928-29 photograph appears more like a complex interplay of geometric forms than a city-scene, as the narrow tower, formed from stark diagonals, seems to intersect a vertical pictorial plane as it plunges to the ground. The interplay of triangles and circles, intensified by the strong contrast of light and shadow, is replicated in the smaller circles clustered around the grid of the tower's base, the overall effect strikingly similar to abstract geometric paintings, of the kind that Moholy-Nagy and his Constructivist peers were creating around this time. The difference, of course, is that this is also an image with a specific subject-matter, and thus a diagram of modern technology's conduits of information and energy. As the critic Lynne Warren notes, the "dense and abstract pattern" is "implicitly celebrating the technological and industrial shaping of modern life."

Moholy-Nagy took a series of photographs of the Berlin Radio Tower, a 450-foot-tall structure completed in 1926; employing aerial perspective, the series exemplifies the artist's belief that photography's primary function was to allow the viewer to engage with reality in previously impossible ways: allowing new levels of detail, new kinds of focus and coloring, perspective and scope. His ideas were expressed in an influential photography book published in 1927 suitably titled Neue Sehen ("New Vision") which, as Lynne Warren notes, explores "the perspectives offered by the modern city - its high-rises and dramatic scales, its geometries of contrast, its industrial patterns and texts."

In its brilliant simultaneous evocation of the geometric principles of contemporary abstract art and the contemporary urban and technological milieu, this photograph is arguably one of Moholy-Nagy's most exemplary works. It can be read with reference to the development of Straight Photography during the 1920s, but also as a work which pushes at the conceptual boundaries of Constructivist principles, readmitting content and theme into the geometric composition.

Gelatin silver print - The Art Institute of Chicago

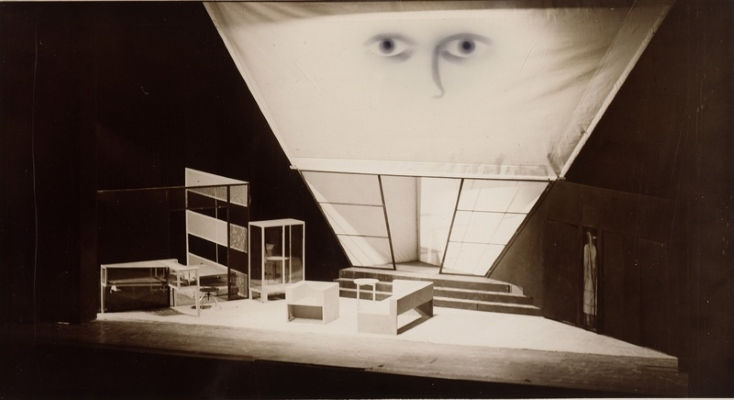

Stage Set Design for Tales of Hoffmann

Tales of Hoffman was Moholy-Nagy's first full theatre design. He created not only the set but also the costumes, and even aspects of the lighting scheme, for the Kroll Opera House's production of Jacques Offenbach's famous work. The opera was generally produced in a gothic, romantic style suited to Offenbach and Hoffman's era, with lavish sets and costumes, but Moholy-Nagy defied expectations in his use of contemporary urban elements such as stainless steel cots and plain white walls. As he stated in interview, "[l]et us test the staying power of so-called great music by having fun with its trappings. If we insist on grand opera, let us see it as contemporaries." Hoping that the production would exemplify his principle of "vision in motion" - an idea of mobile aesthetic form which would approach the complexity and subtlety of a living entity, rooted in his engrossment with light - he began with a series of geometrical drawings. Created in radiant colors, they were intended "to create space out of light and shadow [...] everything is transparent and all these transparences contribute to an elaborate [...] pattern of shapes."

At the Bauhaus, Moholy-Nagy had worked with his friend and colleague Oskar Schlemmer in the school's stage department; Tales of Hoffman was the first theatrical project he undertook after he had left the school for Berlin in 1928. In Berlin, he would become known for his theater designs, with Tales of Hoffman followed shortly by stagings of Madame Butterfly and The Merchant of Berlin. For his treatment of Hoffman's famous macabre tales, Moholy-Nagy pioneered the use of mirrors, film projection, and even amplification in set design. As the critic Edith Tóth has noted, he also elaborated "the idea of musical automata," as "the magnification and doubling of the actor's gestures through the use of mirrors, shadows, and close-up film projection, and simultaneous amplification of their voices, brought about interplay between theatrical distancing and intensification of embodied presence." The art historian Peter Heyworth adds that "[m]achinery and human emotion ... interact so as to reflect the ambivalence that gives the opera its special flavor."

Moholy-Nagy's Hoffman set was seen as a breakthrough in modern operatic mise-en-scène, and also as being unexpectedly well-suited to the subject-matter. As the philosopher and art critic Ernst Bloch asked, what could be "more truly Hoffmanesque than this power to bring ghosts into our world? Without nightgowns, but with machinery? In the cold, phosphorescent world of machines, in the empty chambers of our time, what is suppressed is here liberated in the form of what is to come."

Gelatin silver print - George Eastman House, Rochester, New York

Light Prop for an Electric Stage (Light Space Modulator)

Moholy-Nagy worked with engineer Istvan Sebok and technician Otto Ball to realize his vision for Light Prop for an Electric Stage, also known as the Light Space Modulator. Standing at about five feet tall and powered by an electric motor, the work consists of a large circular base supporting various moving components: a number of metal rectangles which jerk around in irregular fashion, a series of perforated metal discs designed to release a small black ball at a certain point in their rotation, and a glass spiral which rotates to create the illusion of a cone of light. Central to the mesmeric effects the piece was intended to create are 130 integrated electric light bulbs, which shine through different sections of the construction to create complex patterns of light and shadow on the surrounding surfaces.

In fact, Moholy-Nagy's Light Proper was never intended to be a unique art object. Produced in collaboration with the German electronics company AEG, it was intended for commercial use in theaters and festivals. The work was first shown as part of an exhibition by the Deutscher Werkbund ("German Association of Craftsmen") in Paris in 1930, and the same year, Moholy-Nagy created a film showcasing the capacities of the machine, Light Play Black-White-Grey. The film captures the reflections and shadows created by the spinning sculpture, at different times giving the impression of a whirring machine, a factory pumping out futuristic products, and an urban landscape. Moholy-Nagy referred to his modulator as a machine for "creat[ing] pools of light and shadow;" it also embodied many of the principles expounded in his 1922 "Manifesto on the System of Dynamico-Constructivist Forms", co-authored with Alfred Kemeny: "[w]e must put in the place of the static principle of classical art the dynamic principle of universal life. Stated practically: instead of static material construction [...] dynamic construction [...] must be evolved, in which the material is employed as the carrier of its forces."

Moholy-Nagy's Light Space Modulator represents a bold extension of the limits of Constructivist abstraction and stands at the forefront of subsequent developments in Kinetic Art, influencing future artists such as Jean Tinguely and Otto Piene. It also sums up perhaps more than any of Moholy-Nagy's other works his Utopian vision for a total work of art that would transcend all media, approaching the complexity of living, biological form. As the art critic Peter Schjeldahl notes, whether or not "[t]he work was designed for a purpose", "its primary function is to fascinate. Its rhapsodic inventiveness - there had never been anything like it before - puts it in a class of twentieth-century utopian icons."

Aluminum, steel, nickel-plated brass, other metals, plastic, wood, and electric motor - The Busch-Reisinger Museum, Harvard University

Double Loop

This Plexiglas sculpture consists of a series of geometric planes, incised with holes and slits, flowing in biomorphic curves to double back and enfold each other and themselves. The effects of light and viewing perspective continually transform the appearance and mood of the piece, as art critic Chi-Young Kim notes: "[w]hen you walk around the piece in person, the incisions seem to disappear and reappear depending on your vantage point." Moholy-Nagy's use of translucent plastic, combined with his awareness of the ambient effects of light and viewer positioning, is typically prescient, prefigures later movements in modern art such as the 1960s Light and Space movement.

In 1937, having previously fled Germany for England shortly after Hitler's rise to power, Moholy-Nagy emigrated again, this time to Chicago, completing a staggered journey which was repeated by many modern artists during 1930s, as totalitarian regimes became increasingly inhospitable to their presence. The same year he arrived in the United States, he founded the IIT Institute of Design in Chicago, originally known as "The New Bauhaus", an institution that would have a significant impact in spreading the principles of the Bauhaus and European Constructivism to North America. In 1939, to further his work on what he called his Space Modulators, Moholy-Nagy started using Plexiglas, a new industrial material developed in 1934. The Space Modulators blurred the boundaries between painting and sculpture: a Plexiglas sheet, painted and incised on either side, was placed on painted wooden rails so that the sheet would hang a few inches away from the backing board, allowing a complex interplay of light and shadow. He also began working on transparent sculptures such as this one, painting and incising strips of Plexiglas, then heating it in his oven so that he could shape it while it was still warm: a process that incorporated a strong element of chance and creative spontaneity.

Diagnosed with leukemia in 1945, Moholy-Nagy was seriously ill when he made Double Loop, but the freedom of the dynamic form betrays nothing of his doubt or fear of death. By that time, through his pioneering work not only at the Bauhaus but also at the successor institution he had founded in Chicago, he had had a profound impact on the development of modern art across a wide range of media.

Plexiglas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Biography of László Moholy-Nagy

Childhood

László Moholy-Nagy was born in a small farming town in southern Hungary. His father abandoned the family when he was young, and his mother took László and his brothers to live with their grandmother. "I lived my childhood years in a terrible great quietness," he later wrote. Along with his mother and brothers, he left for Budapest in 1913 to study law, but his studies were interrupted when he enlisted into the Austro-Hungarian Army as an artillery officer in 1915. He experienced the horror of war on the Russian and Italian fronts, which remained with him for the rest of his life. During this time as a soldier as he sketched field life, his fellow officers, and the civilians he encountered, he discovered a passion for drawing.

Early Training

In Budapest, encouraged by his friend and mentor the art critic Iván Hevesy, he began taking art classes, studying the Old Masters, especially Rembrandt, as well as the works of the Expressionists and Futurists. His style ranged widely in this early period. He painted landscapes with abstract elements and used bright colors typical of Hungarian folk art to depict technological subjects in a Cubist style. He also developed an interest in photography, encouraged by the photographer Erzsébet Landau.

In 1919, when the Communist Hungarian government, with which he sympathized, was replaced by a military dictatorship, he withdrew to the neighboring city of Szeged, and, after a few months, moved to Vienna. There he joined MA (Hungarian Activism, also referring to the Hungarian word for 'today'), a Hungarian avant-garde group that believed in the revolutionary potential of art. In 1920 he moved to Berlin, then the vibrant hub of Central and Eastern European avant-garde art, where his ideas began to crystallize.

He painted completely abstract works influenced by Dadaism, Suprematism, and Russian Constructivism. He used letters as compositional devices and created photomontages that resembled those of Kurt Schwitters - though his serious and passionate nature did not embrace the sarcasm of Dada. Moholy-Nagy was also intrigued by the paintings of Kazimir Malevich, although he did not accept the Russian's spirituality. El Lissitzky and the Constructivists were his primary influences at this time. He experimented with transparency in color as he overlapped geometric shapes, believing in the Constructivist affirmation of art as a powerful social force that could teach workers to live in harmony with new technology.

Although Moholy-Nagy considered himself primarily a painter throughout much of his career, he also produced a great deal of photography. His first wife, Lucia, whom he met in Berlin in 1920, was a talented photographer and went on to record the Bauhaus years with her camera. They experimented with "photograms" (camera-less photographs in which light-sensitive paper is exposed directly to light), which allowed Moholy-Nagy to explore light and shade, transparency, and form. In 1922, his success as a painter secured him a solo show at Galerie der Sturm, the most popular gallery in Berlin. A year later he received an invitation to teach at the Bauhaus from Walter Gropius.

Mature Period

From 1923 to 1928, Moholy-Nagy taught at the Bauhaus, an influential school of architecture and industrial design that provided students with groundwork in all of the visual arts. His recruitment to the faculty marked a turning point in the school's direction since he was given control of the school's crucial preliminary course, or Vorkurs. Rather than endorsing the individualism of Expressionist painting, he introduced a new emphasis on the unity of art and technology. Moholy-Nagy's gregarious disposition made him a natural teacher. He taught the metal workshop, taking over from Paul Klee, which designed a line of lighting fixtures under his direction that are still in use today.

He also co-edited the periodical Bauhaus with Gropius, who became his mentor and lifelong friend. They co-published the Bauhausbucher, the fourteen books that acted as the manifesto of the Bauhaus faculty. He designed the typography for the books and wrote two influential ones himself. Painting, Photography, and Film was published in 1925. The second book, and the 14th in the series, From Material to Architecture, was published in 1930 (this was translated as The New Vision: From Material to Architecture in 1932) and offers a summary of Moholy-Nagy's Vorkurs.

Political pressure in the late 1920s prompted Moholy-Nagy to resign from the Bauhaus. Next, he explored a variety of creative fields to support his family, no longer identifying himself as a painter. Socialists and Nationalists alike attacked his controversial stage sets for the Krolloper, an experimental opera house in Berlin, for the overt use of machinery that dwarfed the human figure onstage.

Moholy-Nagy expressed himself more fully in the 11 films he made between 1929 and 1936. His first film, Berlin Still-Life (1931), follows a documentary style he often employed. However, it was his famous Light-Play, Black-White-Gray of 1930 that was distinctly avant-garde. In 1932, he and Lucia separated, and he married his second wife, Sibyl, whom he had met at a film production studio. Their daughter Hattula was born in 1933.

Political tension and rise to power of the National Socialists in 1933 led Moholy-Nagy and his wife to emigrate. They moved to Holland temporarily in 1934, then to London in 1935. Moholy-Nagy discovered an international group of artists and intellectuals who had also fled there, finding many opportunities for industrial design. However, he was not satisfied with the situation in London as he truly sought an artist community and a chance to re-create the Bauhaus. His second daughter, Claudia, was born amid his busy work life and just before an opportunity to return to Berlin. A British film agency asked him to record the Olympic Games of 1936, as he described it to capture, "the spectator psychology, the physiognomic contrast between an international crowd and the rabid German nationalists," but, disgusted at finding that former friends and students in Berlin had become Nazis, he quit after three days, telling the agency, "I'll never go back to Germany." In 1937, a door opened for the artist when he was recommended by Gropius to direct a new art school in Chicago.

Late Years and Death

From 1937 to 1946, Moholy-Nagy dedicated himself to teaching as much as to his own work. He negotiated a five-year contract as director of the New Bauhaus in Chicago, but the school went bankrupt after its first year. While the faculty stood by him, Moholy-Nagy faced personal attacks by the Executive Committee, which instilled his distrust of industrialists. Against all odds, he re-opened the school in 1939 as the School of Design and recruited a board of art supporters who agreed with his educational philosophy, including Walter Gropius, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., and philosopher John Dewey. Moholy-Nagy and the faculty supported themselves through other work and taught at the School out of devotion. The start of World War II presented new challenges as the draft depleted the school of both faculty and students. However, Moholy-Nagy's inventiveness kept the school alive, and he found ways for the school to contribute to the war effort through ideas for camouflage and other ventures.

Moholy-Nagy worked tirelessly at a multitude of projects, including teaching and administering the school, dictating a new book, Vision in Motion (1947), and working in industrial design to support his family. In 1944, a board formed by industrialists friendly to the educational ideas of the school offered to support its administration and finances to the newly named Institute of Design.

Moholy-Nagy, however, became seriously ill and was diagnosed with leukemia in November 1945. After x-ray treatment, he returned to work as diligently as ever. In November 1946, he attended the Museum of Modern Art's Conference on Industrial Design as a New Profession. This conference was his last stand for his ideas of art education, especially the idea that art should guide industry rather than industrialists dictate design. He died from internal hemorrhaging soon after his return to Chicago.

The Legacy of László Moholy-Nagy

Moholy-Nagy's influence on modern art is felt broadly in several disciplines. Along with the other emigres from the Bauhaus, he succeeded in instilling a modern aesthetic into modern design. His impact was felt most strongly by his students, but his use of modern materials and technology impressed other young designers, including Charles Eames, who visited the New Bauhaus while studying at the Cranbrook Academy of Art. In addition, by combining photography with typography to create what he called the typo-photo, Moholy-Nagy is considered by many to be the initializer of modern graphic design.

Moholy-Nagy's influence on photography is felt equally through his writings as through his photographs and photomontages. His first Bauhaus book established photography as a fine art equal to painting. His experiments in light and shadow reinforced photography's value as a subjective medium, and therefore an artistic medium, rather than simply a means to document reality.

Recent years have brought international attention to Moholy-Nagy's achievements with several major museums organizing retrospectives, including the Tate Modern in London, the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, and the Loyola University Museum of Art in Chicago, that celebrate the impact of his work on American art.

Influences and Connections

-

![Walter Gropius]() Walter Gropius

Walter Gropius ![Lajos Kassak]() Lajos Kassak

Lajos Kassak![Paul Scheerbart]() Paul Scheerbart

Paul Scheerbart![Herbert Read]() Herbert Read

Herbert Read

![Robert Brownjohn]() Robert Brownjohn

Robert Brownjohn![Marianne Brandt]() Marianne Brandt

Marianne Brandt![Charles Eames]() Charles Eames

Charles Eames![Herbert Bayer]() Herbert Bayer

Herbert Bayer![Gyorgy Kepes]() Gyorgy Kepes

Gyorgy Kepes

![Geometric Abstraction]() Geometric Abstraction

Geometric Abstraction

Useful Resources on László Moholy-Nagy

- The New Vision: Fundamentals of Bauhaus Design, Painting, Sculpture, and ArchitectureOur PickBy László Moholy-Nagy, Daphne M. Hoffmann

- Vision in MotionBy László Moholy-Nagy

- The New Vision...And Abstract of an ArtistBy László Moholy-Nagy