Summary of Gesamtkunstwerk

The German term Gesamtkunstwerk, roughly translates as a "total work of art" and describes an artwork, design, or creative process where different art forms are combined to create a single cohesive whole. The idea was popularized by the composer Richard Wagner who argued for the "consummate artwork of the future," where "No one rich faculty of the separate arts will remain unused in the Gesamtkunstwerk of the Future". Remaining most popular in Germany and Austria, the concept was developed throughout the 19th and into the early 20th century by a range of European art movements and became a core tenet of modern art. Although it fell out of favor in the post-modern period, the term is still sometimes used today to describe multimedia artworks and installations.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Gesamtkunstwerk survives most prominently in architecture, where all aspects of the design; interior, exterior and furnishing were created to complement one another and this influence can be seen in the artistic practice of movements including Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Jugendstil, the Vienna Secession, the Bauhaus, and De Stijl.

- Concepts of Gesamtkunstwerk were often aligned with the wider values and beliefs of the art movements that adopted it and the collaboration of arts and artists that created Gesamtkunstwerk was viewed as having the potential to create a more equitable and, ultimately, utopian society.

- Some of the forms of Gesamtkunstwerk had close associations with nationalism. For instance, the Arts and Crafts Movement promoted traditional English craftsmanship. More tragically, some of Wagner's views and work can be seen as forming the foundations of Nazi philosophy and his ideas of traditionalism in music helped to offer legitimacy to the new party. This association caused the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk to be rejected by many artists after the Second World War.

Overview of Gesamtkunstwerk

The Palais Stoclet (1905-10) represents the ultimate environment envisioned by the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshops) group, a total work of art that allowed for all aspects of the building to be cohesively designed.

The Important Artists and Works of Gesamtkunstwerk

The Red House

This photograph depicts the exterior of The Red House, named for the red brick used for its walls and the red tiles of its roofing. Morris saw the house as "very mediaeval in spirit" and the sloping and overhanging gables, prominent chimneys, and combination of round and narrow vertical windows reflect the influence of early English Gothic architecture. Innovative in its rejection of any architectural decorative elements, the building's design was, as J. W. Mackail wrote, "plain almost to severity, and depended for its effect on its solidity and fine proportion". Every element, from the site, which was then a rural setting in Kent on the outskirts of London, to the interior fittings, were designed to create a singular work of art.

Following his marriage, Morris built this house with Philip Webb, and the design, materials, and building methods reflected his emphasis on traditional handcrafts and utility. Built upon a L-plan, Morris designed the windows, employing a number of different types and shapes, to suit the layout and purpose of the rooms. He also worked with a wide range of other artists on the property, including Burne-Jones who created a selection of stained glass, Dante Gabriel Rossetti who produced painted panels and other elements were designed by Ford Madox Brown, Elizabeth Siddal, and Jane Morris. Designing the garden, Morris emphasized its integration with the house and he saw the building and grounds, and the collaborative approach they had employed to make it, as an artistic statement of his vision of "the future we are now helping to make". He also noted that "If I were asked to say what is at once the most important production of Art...I should answer, A beautiful House". During the five years that Morris lived in The Red House, it became an active center of the arts, informing both the Arts and Crafts movement and the Pre-Raphaelites, while also having a significant influence as a pioneering example of Gesamtkunstwerk. In the 1950s the architects Edward and Doris Hollamby renovated The Red House, which had fallen into disrepair, and it again became an important hub for artists and thinkers.

Red Brick, clay slate, wood - London

Bayreuth Festspielhaus or Bayreuth Festival Theatre

The façade of the Bayreuth Theatre reflects late-19th century fashions in architecture, with its columns and geometric patterns of light-colored stone framing the central entrance. Imposing, and referencing the appearance of a classical temple, it rises on a small hill above a garden laid out in a geometric design which reflects the decoration on the frontage. Richard Wagner built the theatre as a venue for the performance of his opera cycles at the annual Bayreuth Festival, officially titled Richard-Wagner-Festspielhaus, which still continues today. As such, the theatre and its performances embodied his vision of Gesamtkunstwerk, with every element combining to create a total aesthetic experience.

The foundation stone for the building was placed on Wagner's birthday in 1872 and Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung,) Wagner's cycle of four operas opened the theatre in 1876. To integrate the presentation of the operas with the building, Wagner pioneered a new design, including continental seating (a seating layout without a central aisle), a double proscenium, and a recessed orchestral pit. He also primarily used wood for the interior to improve acoustics. The continental seating, arranged in a single wedge, meant every seat had a clear view of the stage. The double proscenium created what Wagner called a "mystic gulf" between the stage and the audience, enhancing the dreamlike and mythic quality of his operas. At the same time, the orchestra pit, hidden under the stage, was invisible and let the audience focus entirely on the opera. Many theatres subsequently adopted these features.

Brick, wood, glass - Bayreuth, Bavaria, Germany

Hôtel Tassel

This townhouse, considered to be one of the first complete examples of an Art Nouveau building, was revolutionary in its architectural techniques and its fluid, open style. Innovating with modern materials, particularly steel and glass, Horta emphasized organic, curving lines, so the façade flowed both vertically and horizontally. He pioneered the use of thin iron columns, rather than conventional stone, allowing for the large windows. Horta also designed the interior, giving the property an open floor plan and emphasizing natural light, so that the total effect of the building was of a fully-integrated, light-filled space. The wider design was complemented by details such as the light fixtures, window frames, door handles, and stair railings which imitated sinuous plant-like forms, defining both the wider Art Nouveau aesthetic as well as creating a cohesive decorative and architectural scheme throughout the property.

Along with Horta's Hôtel Solvay, Hôtel van Eetvelde, and Maison & Atelier Horta, this building was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2000 and cited, as "some of the most remarkable pioneering works of architecture of the end of the 19th century. The stylistic revolution represented by these works is characterised by their open plan, the diffusion of light, and the brilliant joining of the curved lines of decoration with the structure of the building."

Iron, stone, glass - Brussels, Belgium

Ernst-Ludwig-Haus

A leading example of Gesamtkunstwerk within the Jugendstil movement, this building was the centerpiece of the Darmstadt Artists Colony (founded in 1899) and it served as artist's studios. Recruited by the Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig to design the colony, Olbrich was a leading figure of the Vienna Secession and had designed the famous Secession exhibition building three years before. Olbrich seized the opportunity to create a building that fused architecture, sculpture and decorative elements. The influence of the Vienna Secession can be seen in the white walls and decorative gold frieze around the entrance. The large windows demonstrate the practicality of the building and the monumental male and female statues by the sculptor Ludwig Habich's on either side of the stairs point to its purpose, representing strength and beauty.

Today the Ernst-Ludwig-Haus houses the Mathildenhöhe Institute, which promotes contemporary art, while UNESCO named the Darmstadt Art Colony as a World Heritage site in 2015, calling the colony "a unique ensemble testifying to experimental creativity."

Brick, plaster, glass, iron, tile - Darmstadt

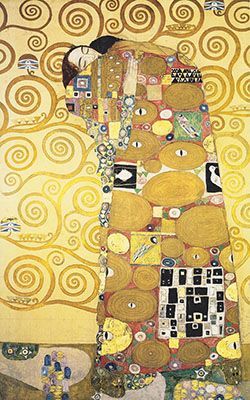

Preparatory design for the interior of Stocklet Palace

This stunning design shows a couple in an intimate embrace, a common motif of Klimt's work, and rendered in his distinctive style, using a gold background of elegant spirals. The couple is simplified, the woman's upturned face partially visible against the man's black hair, as her right arm clasps his shoulder. The shape and pattern of the man's cloak, combining gold ovals, with a grid of black and white, and other jewel colors, creates a feeling of unity between the couple and the setting.

This cartoon was one of nine, created on a 1:1 scale by Klimt for the Stoclet Frieze (1910-11), decorating the dining room of the Palais Stoclet in Brussels. His designs were executed as mosaics, following his specific directions and using precious materials, including mother-of-pearl, gold leaf, and enamel, by the Wiener Werkstätte and the Wiener Mosaikwerkstätte (Vienna Mosaic Workshop). Two twenty foot murals graced both sides of the dining room, while a smaller vertical panel, The Golden Knight, presided at the head of the table. The Vienna Secession architect, Josef Hoffman designed and built the luxuriant house for Adolph Stoclet, a wealthy banker and noted art collector, from 1905-11. Wiener Werkstätte artists, including Koloman Moser, Carl Otto Czeschka, Ludwig Heinrich Jungnickel, and Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill, along with Klimt, designed the interior.

Each element of the palace was specifically designed and made of the finest materials, irrespective of the cost, and as architectural critic Aaron Betsky wrote, "The sensuousness of the textures, culminating in the 20-foot murals that Gustav Klimt created to grace the walls of the dining room, conflates Ali Baba's treasure cave with a built version of haute couture: you surround yourself with visible wealth and luxuriate in it. Every moment of parquetry, marble, onyx, or hardwood is itself an exercise in geometry carried out in a dizzying variety of patterns. Everywhere you look, every aspect of life, from how you sit to what you see, has become an example of human ability to craft a complete environment." Named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, the organization cited the building as "one of the most accomplished and homogenous buildings of the Vienna Secession...embodying the aspiration of creating a 'total work of art' (Gesamtkunstwerk)."

Chalk, pencil, gouache, silver, gold, platinum, transparent paper, draft paper - MAK- Austrian Museum of Applied Arts/Contemporary Arts, Vienna, Austria

Imperial Hotel

The façade of the Imperial Hotel combined Wright's Prairie Style with the Mayan Revival style, as well as being informed by Japanese influences. At the entrance, a reflecting pool, framed by two large stone figures, evoked Mayan plazas. The motif continued throughout, as seen in the pair of short thick stone columns and the temple-like entrance way, as the visitor entered the building through a low and dark hallway before ascending the stairs into the spaciousness of the central lobby. Wright painstakingly designed all the elements and fittings of the hotel, notably creating tall columns, their surfaces incised with patterned openings to create light, so that they were dubbed "pillars of light." Due to their patterns, the columns also evoked Mayan hieroglyphs, while at the same time their light filled presence resembles the Japanese floating latterns that inspired Wright.

The Japanese government commissioned Wright to create a hotel complex that would attract Westerners. Building in an area known for devastating earthquakes, he expertly engineered the building, using massive concrete piles and a H-shaped plan. At the same time, made primarily of brick, the building is hand-constructed, evoking the Arts and Crafts movement. Like the artists of the Arts and Crafts movement, Wright coordinated the hotel's furnishings, including tableware and china, with the architecture to create one of his most completely realized examples of Gesamtkunstwerk. In 1968 most of the building was demolished to make way for a new high-rise while the central section was relocated and reconstructed at the Meiiji-Mura Museum.

Reinforced concrete, Oya stone, brick, glass, wood, copperplates - Meiji Mura, Near Nagoya, Japan

Rietveld Schröder House

Emphasizing interlocking rectangles, horizontal and vertical lines, and grey, black, or white mixed with primary colors, this architectural manifesto exemplifies De Stijl's approach to Gesamtkunstwerk. Designed with sliding or revolving panels, the interior space created a fluid openness that reflected the underlying values of openness in relationships, freed of hierarchal and traditional constraints. The line, color, and surface of the exterior's rectilinear lines flow, uninterrupted, into the interior space. Every detail of the design was carefully considered, as seen in the radical design of the windows, which open at a ninety-degree angle, emphasizing their rectangular form.

Reitveld designed the house, considered by some scholars to be the only true example of De Stijl architecture, as a private residence for Mrs. Truus Schröder-Schräde and her three children. Naming the house a World Heritage Site in 2000, UNESCO stated, "With its radical approach to design and the use of space, the Rietveld Schröderhuis occupies a seminal position in the development of architecture in the modern age."

Reinforced concrete, steel, brick, plaster, wood, glass - Utrecht, Netherlands

Bauhaus Building

This iconic building with its geometric design, glass curtain walls with the steel structural grid exposed, its color scheme and signature typography embodies the Bauhaus aesthetic in every way. Here, Gesamtkunstwerk is applied within a vision of total design that incorporates modern technology and industrialization. When the Bauhaus moved from Weimar to Dessau, Gropius, influenced by the design of the Fagus Factory (1911-13), took the opportunity to design a campus that reflected the principles of the school. Using the new technology of reinforced concrete and steel, he designed each space to embody its function. The use of the glass curtain and large ground floor windows illuminated workshops and studio spaces, while movable partition walls and interior spaces were designed for flexibility and openness, enhancing community collaboration. Students and artists in all Bauhaus departments were involved in designing various interior fixtures and fittings, as reflected here in the exterior's use of Herbert Bayer's font, invented at the Bauhaus.

Gropius also designed a five-story housing block for students and homes for the Bauhaus Masters, all reflecting the same use of modern construction technology with an emphasis on geometric style. The campus itself was innovative as architectural critic Nikil Saval wrote, "It was a school that was also - unusual for Germany - a campus: a place where students and teachers came to live. It was meant to embody the life that its teachers and students were also expected to make available to the world." Gropius described his own vision, "The ultimate aim of all artistic activity is building! The ultimate, if distant, aim of the Bauhaus is the unified work of art," a vision which included the union of technology, fine art, and crafts in what he called a "total architecture." UNESCO named this site, along with the Bauhaus in Weimar and Bernau, a World Heritage Site in 1999. The work of the Bauhaus and its concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, defined by Gropius as "total design" was internationally influential, as Bauhaus art and architecture trends developed in the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Australia and Israel.

Glass, steel, reinforced concrete - Dessau, Germany

Beginnings

Early Trends

Ideas related to Gesamtkunstwerk existed as early as the Baroque period. These can be seen in Johann Fischer von Erlach's monumental designs for Schönbrunn Palace (1696-1709) or Louis le Vau and Charles le Brun's designs for Versailles (c. 1661-1678), the residence of Louis XIV of France. Architecture, interior design, garden design, sculpture, and painting were combined in one total effect of grandeur that was reflected in every element from the tableware to the textiles. Later architects and artists expanding the royal estates continued to strive for a total effect, although they also reflected the influence of later styles. This can be still seen in the additions at Schönbrunn Palace by Rococo architect Nicolaus Pacassi. UNESCO, naming Schönbrunn Palace a World Heritage Site in 1996, called the buildings and grounds "a remarkable Baroque ensemble and a perfect example of Gesamtkunstwerk", demonstrating how well Pacassi's work blends with the original.

German Romanticism

Early 19th century Romanticism movement influenced the development of Gesamtkunstwerk, notably through the artist and theorist, Phillip Otto Runge. Runge was celebrated for his Tageszeiten (Time of the Day) (1803-1805) series that depicted specific times of the day as a holistic imagining of figures, natural forms, architectural and decorative motifs, and landscapes. Taken as a kind of precursor of Gesamtkunstwerk, Runge's work had a noted impact on German artists, particularly as the leading figure of the day, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe became a patron. Contemporary historian Rudolf M. Bisanz notes that Runge "expanded under the auspices of the visual arts...the Gesamtkunstwerk on the basis of the universal constancy of human predisposition and an ecumenical Christianity."

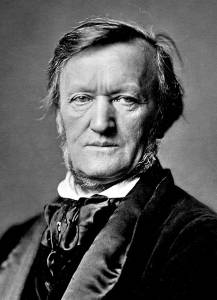

Richard Wagner

In 1827 K.F.E. Trahndorff, a German writer and philosopher, used the word Gesamtkunstwerk in his Ästhetik oder Lehre von Weltanschauung und Kunst (Aesthetic or Theory of Worldview and Art). Although the first to coin the term, he built on the views of other philosophers such as Ludwig Trek and Gottfried Lessing who advocated for a synthesis of the arts. Adopting the idea theoretically and embodying it in his renowned operas, Richard Wagner popularized the term to the degree that, subsequently, it was often attributed to him. His essays, such as "The Art Work of the Future" (1849), argued that, since the classical Greeks, the arts had been incoherently splintered from one another, and that the artwork of the future must return to creating a total work of art. Wagner felt that the 19th century was one of chaos, and wrote "It is for Art above all else, to teach this social impulse its noblest meaning, and guide it towards its true direction." His noted opera cycles, particularly Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876), made him the most famous and influential composer of his era, as he combined drama, poetry, music, and theatrical setting to create a single unified experience. In 1857 he also undertook the design and building of the Bayreuth Theatre in Bavaria, creating a complete environment for the performance of his opera cycles.

Wagner's anti-Semitism expressed in such works as "Das Judenthum in der Musik" (Judaism in Music), an essay published under a pseudonym in 1850 and then under his own name in 1869, combined with his emphasis on the superiority of Germanic culture were seen as foundational to Nazism and Hitler was an ardent fan of his music and performances. Although Wagner himself died in 1883, by the 1920s, Winifred Wagner, the composer's daughter-in-law who had assumed ownership of the Bayreuth Theatre and its festival, was a close friend and strong supporter of Hitler. In 1928, she along with the festival's leadership joined with the Nazi Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur (The Militant League for German Culture).

Arts and Crafts Movement (1880-1920)

An early example of modern Gesamtkunstwerk was The Red House (1859), codesigned by William Morris and Philip Webb in Southeast London. The house, drawing upon Medieval Gothic design and using traditional building methods and materials, was also a pioneering example of the Arts and Crafts movement. Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones also helped to decorate and fit the interior, while Morris designed the exterior garden, all to create a single artistic effect. Rossetti described the result as "more a poem than a house," and, as the thriving hub of the Arts and Crafts movement, as well as the site where Morris formed his design company, the building became an influential example of Gesamtkunstwerk. The movement's concept of Gesamtkunstwerk emphasized handmade objects over mass production, and focused on an English tradition of craftsmanship dating back to the 13th century, a period that also informed their aesthetics.

Art Nouveau (1890-1905)

One of the first examples of Art Nouveau was Victor Horta's Hôtel Tassel (1893) in Brussels, a private residence that he designed for the Tassel family. The same year Paul Hankar's Hankar House (1893) also pioneered the style, as did Henry Van de Velde's house, Bloemenwerf (1895). In all of these houses the architecture, fittings, and furnishings were designed to complement each other and produce a complete artistic effect. As art historian Kenneth Frampton writes, Van de Velde built a house for himself that "without question was intended to demonstrate the ultimate synthesis of all the arts, for apart from integrating the house with all its furnishings, including the cutlery, Van de Velde attempted to consummate the whole GESAMTKUNSTWERK through the flowing forms of the dresses that he designed for his wife".

Art Nouveau dominated the 1900 Paris International Exposition, an international showcase that, along with Van de Velde, included Bruno Paul, Louis Comfort Tiffany, René Lalique, Fvodor Schechtel, Josef Hoffman, Émile Gallé, Alphonse Mucha, and many others. Art Nouveau embraced the use of modern materials, including iron, glass, ceramics, and, eventually, concrete, while emphasizing curving sinuous lines and organic forms to create a sense of movement. It was widely employed in all elements of interior design, the graphic arts, metal work, and jewelry as well as architecture.

Jugendstil (1896-1914)

Jugendstil, the German term for Art Nouveau, began in 1896 in Munich with the work of Hermann Obrist. As art critic Andrew Hickling notes his "'whiplash'; a sinuous flourish of hairpin curves inspired by cyclamen stems...would become synonymous with fin-de siècle design." In much the same manner as Art Nouveau, the emphasis upon elegant lines, inspired by organic and sometimes geometric forms, involved a new vision of design that, rejecting conservative academic art, integrated all the arts into a Gesamtkunstwerk.

Founded in 1899 by the Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig of Hesse, the Darmstadt Artists' Colony became the hub of the Jugendstil movement, but also its most famous example of Gesamtkunstwerk. Led by Joseph Maria Olbrich, the artists who lived and worked in the colony included architect Peter Behrens, sculptor Ludwig Habich, painter Hans Christiansen, interior designer Patriz Huber, and furniture designer Julius Glückert. Each artist's home was a carefully-designed total work of art, while also harmonizing with the colony's wider architecture effect and reflecting its owner's artistic preoccupations. For instance, Olbrich's façade for Hans Christiansen's house was decorated with bright colors and figurative decoration to reflect the painter's artistic oeuvre. Olbrich's Ernst-Ludwig-Haus, (1900-1901) was the center of the colony, functioning as a public reception space but also housing artist studios and workshop space. Rejecting the hierarchal distinction between fine and applied art and emphasizing craft, the colony's workshops also embraced modern industrialization, producing various items commercially and promoting the idea that even the most ordinary home could be a Gesamtkunstwerk. In 1901 in their "A Document of German Art," written for the colony's official opening, Olbrich and Behrens celebrated the colony as a model of Gesamtkunstwerk.

The Vienna Secession (1897-1905)

Breaking with the conservative and academic hierarchy of the arts, the Vienna Secession emphasized an international "total art," that unified the decorative arts with painting, sculpture, and architecture. Founded in 1897 the movement was led by Gustav Klimt and included the architects Josef Hoffmann and Joseph Maria Olbrich, the designer Koloman Moser, and, later, the architect and designer Peter Behrens. The Secession's first and most famous project was the Secession Building (1897-1898) in Vienna, designed by Olbrich and serving as the movement's exhibition space. The building's architecture, its famous Beethoven Frieze (1901), designed by Gustav Klimt, and the distinctive façade details, designed by Moser, created a total work of art that also functioned as the movement's architectural manifesto. The tour de force of the movement was the Stoclet Palace (1905-11) in Brussels. Designed by Josef Hoffman, the private residence with its dining hall, containing murals by Gustav Klimt and employing rare and expensive materials, has been celebrated as the luxurious epitome of Gesamtkunstwerk. The Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshops), a commercial design group founded by Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser in 1903, played a primary role in creating elements for the Stoclet Palace (1905-11), including executing Klimt's murals made of precious materials.

Bauhaus (1919-1933)

Taking leadership of the Bauhaus, a school that emphasized rigorous training in the crafts along with the fine arts, Walter Gropius embraced the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk. In 1919 his Manifesto proclaimed the "universally great, enduring spiritual-religious idea..., which must find its crystalline expression in a great Gesamtkunstwerk." Redefining the term from a "total work of art," to what he called "Total Design," he believed the concept applied to all aspects of modern life, from designing a factory to urban planning to a private residence, and to all of its elements from workstations to lighting, teapots, and teaspoons. Believing that form should reflect function, under Gropius' management, the Bauhaus ardently embraced the materials and processes of modern technology and a modernist aesthetic to create a new utopian society.

De Stijl (1917-1931)

In 1917 Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian, with other artists, founded De Stijl, a Dutch movement that advocated for simplicity, using primary colors and geometric forms, to create abstract works that reflected underlying spiritual reality. Other noted artists who later joined the movement included Gerrit Rietveld and Vilmos Huszár. Van Doesburg was deeply interested in Gesamtkunstwerk's unification of fine art with architecture and the applied arts to create a kind of utopia. De Stijl became primarily known for its paintings, as exemplified by the Mondrian's Neo-Plasticism and van Doesburg's Elementarism, but the group also produced items including graphic design and Rietveld's iconic chair. Rietveld was the creator of one of the movement's most renowned buildings, the Rietveld Schröder House (1924), which incorporated interior and exterior space into one total art work that emphasized, according to historian Alice T. Friedman, "a fierce commitment to a new openness about relationships within their own families and to truth in their emotional lives."

Concepts and Trends

Raumkunst

The Jugendstil artist August Endell pioneered the concept of Raumkunst, or "room art," as all the elements in a room from furnishings to fittings to decorative motifs were designed to create a total work of art. He derived Raumkunst from his concept of Raumbewegung, or "space-movement," as he wrote, " It is the life of space (Raum) that gives...such a strong and meaningful basis to form and color...It is customary to understand under the term architecture the elements of a building, the facades, the columns, and the ornaments. And yet all of this is only secondary. What is in fact most powerful is not form, but...the emptiness that spreads out rhythmically between walls, that is defined by them, but whose liveliness is more important." At the 1899 Dresden German Art Exhibition, Richard Riemerschmid exhibited his Music Room, and at the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle, Bruno Paul's Hunting Room, Bernhard Pankok's Smoking Room, and Riemerschmid's Room for an Art Lover were exhibited. These rooms, each presented as a total work of art focused around the room's function, were wildly popular and most of the items went immediately into commercial production. The concept of living in a total work of art became available to the ordinary middle class, who could not afford custom buildings, but who could now transform their interior rooms with commercially available items. The concept of Raumskunst implicitly informed the later work of the Bauhaus and De Stijl, though modified. Walter Gropius emphasized function and total design, whilst De Stijl sought to create interior spaces that were open and flowing. Both Bauhaus and De Stijl, embracing modernization and its processes, commercially producing many of their products.

Multimedia

In essence, Gesamtkunstwerk prefigured modern multimedia practice and this interdisciplinary approach was expressed in the lives of its practitioners. At the time of his death, William Morris was remembered as much for being a poet as for his design work. Otto Eckmann created graphic work, logos, and several distinctive fonts, while also engaged in decorative painting, and Paul Bruno was not only a leading architect but also an interior designer, furniture designer, and illustrator. Rather than specializing in a single art, artists took a "Renaissance man" approach, continually learning new crafts, printing technologies, industrial processes, and artistic techniques to expand their repertoire to all aspects of designs. At the same time, the interdisciplinary approach led to an emphasis on collaboration, as artists and craftsman worked together on a single project.

Visions of Utopia

Beginning with the works of Richard Wagner, Gesamtkunstwerk was driven by the vision that the total work of art would reflect and create a utopian society. In many cases, including Wagner and the Arts and Crafts movement, the utopian society was, in essence, a revival of an earlier age. Wagner sought a return to the unity he saw in classical Greece and the Arts and Crafts movement saw that restorative value in the earlier, simpler age of medieval England. As a result, Gesamtkunstwerk often had an implicitly nationalistic focus, drawing upon the traditional crafts and beliefs of a particular people. As art historian Michael Wilson Smith writes, the concept embodied "an attempt to forge many cultures into a single, idealized national culture." By the 1920s, this emphasis had informed Nazism's extreme nationalism, defined by spurious concepts of racial and cultural purity.

Other movements, like Jugendstil and Art Nouveau saw Gesamtkunstwerk as connecting humans to the order and truth of nature, as artists turned to organic forms. These depictions were assisted by then-recent scientific observations including microscopic photographs. De Stijl saw their abstract elemental forms and primary colors as reflecting a deeper spiritual reality, where Gesamtkunstwerk would create a new openness in society.

Later Developments

Gesamtkunstwerk was not without its critics and in the 1920s the German playwright Bertolt Brecht compared it to hypnosis. He wrote, "So long as the expression "Gesamtkunstwerk" means that the integration is a muddle, so long as the arts are supposed to be "fused," together, the various elements will all be equally degraded and each will act as a mere "feed" to the rest." He advocated for a "radical separation of the elements." The noted filmmaker Eisenstein, while influenced by Wagner in his concept of "total cinema," similarly emphasized a separation of elements with his use of montage, juxtaposing discordant and contradictory images. As art critic Dustin Cosentino wrote, "Where there is totality, there is total control. And total control means that the successfully executed Gesamtkunstwerk...does not allow for free progression or natural evolution."

The concept of Gesamtkunstwerk fell from favor in the 1930s with the rise of Nazism, partly due to the displacement of many of its leading practitioners. Artists such as Walter Gropius and other members of the Bauhaus fled from Nazi persecution, moving to other European countries or to the United States. As the same time, however, Nazism co-opted some of the concepts of Gesamtkunstwerk and Wagner's music and theory was seen as foundational to ideas of racial purity. Reviving Nordic myth and culture during World War II, the Nazi party ran the Bayreuth Theatre Festival, presenting Wagner's operas as well as lectures on the composer. As a result, in the post-war period, the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk lost all legitimacy and artists such as Peter Behrens, who remained in Germany and worked with Speer at Hitler's behest, were disgraced. At the same time, the effect of the war and its atrocities made belief in a total work of art as a vehicle for a utopian society untenable in the post war era. Emerging art movements also rejected any concept of the unity of all the arts, as seen in Abstract Expressionism's emphasis on the formal qualities and media specificity of painting.

Contemporary scholarship has revisited and revitalized the historical and artistic analysis of Gesamtkunstwerk. Scholars such as M.W. Smith in his The Total Work of Art (2007) writes, "the total work of art is still a potent aesthetic idea, always intertwined with technology, continuing to blur distinctions between high and mass culture, artwork and commodity spectacle." As Smith noted, "The uses to which it had been put under the Third Reich made the Gesamtkunstwerk generally unacceptable throughout much of Europe in the wake of the Second World War. The genre, however, would find new life in the United States." Smith finds this "most sharply exemplified at Disneyland, which replicated many of the strategies of Bayreuth, the Bauhaus, and Nuremberg." His analysis also includes Warhol's multimedia Happenings, virtual reality and the pseudo-totality of the internet, as informed by the concept.

Other scholars including David Robers, Matthew Wilson Smith, and Juliet Koss also view the concept as central to twentieth century culture. As Art critic David Newland notes, "The multi-media installations so ubiquitous in contemporary art - such as Marta Minujin's raucous performance installations - are arguably indebted to the idea of the gesamtkunstwerk." Various events, including the opening ceremonies for the Olympic games, the Times Square New Year's Eve celebration, as well as concert performances by Laurie Anderson, Robert Wilson & Philip Glass, Madonna, Nine Inch Nails, and others have been viewed as aspiring to total works of art. Whilst various critics have applied the term retrospectively, none of the artists themselves have embraced or employed it.

In 2014, the Saatchi Gallery's exhibition Gesamtkunstwerk: New Art from Germany, a show that included over twenty contemporary artists, was described as pointing "to a new kind of Gesamtkunstwerk, one in which high and low culture, the avant-garde and the historical, the everyday and everything in between can co-exist." To avoid the negative connotations of the term, the exhibition emphasized the egalitarian and democratic aspects of the works.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI