Summary of Victor Horta

Many creative minds have been said to be undisciplined in their youth. Belgian architect Victor Horta's biographers have even gone further, describing him as "lazy" and a "dunce" as a teenager. Apparently, Horta's father eventually had enough, and as punishment, at age 16 Horta was sent to work on a construction site. There, as he later recalled, he had an epiphany, and saw the rest of his life laid out before him. Indeed, Horta would go on to become one of his country's most accomplished and innovative architects, and one of the first following Belgian independence to achieve international renown, as one of the founders of Art Nouveau in the 1890s. Horta turned to Art Deco as his professional fortunes declined in the aftermath of World War I, and though he was later to receive numerous honors late in life, he had faded largely into obscurity by the time of his death, and several of his key works have been lost. In the last fifty years Horta's reputation has dramatically recovered and he is now recognized for being one of the world's key designers at the dawn of the 20th century.

Accomplishments

- Horta is famous for his pioneering work in Art Nouveau and the translation of the style from the decorative arts into architecture in the early 1890s. Horta's inventiveness with Art Nouveau helped to make it something of a national style in Belgium by 1900 before its swift demise in advance of World War I.

- Horta's work in Art Nouveau is marked by a keen understanding of the capabilities of industrial advances with iron and glass as structure and infill. Horta's buildings disclose an honest handling of their materials' properties, particularly the ability of iron to be twisted and bent into hairpin forms that extend seamlessly into the accompanying décor, inside and out, making the buildings "total works of art."

- Horta was an adaptable architect who transitioned from Art Nouveau to other styles such as Art Deco as public tastes dictated. Though Horta was respected during his lifetime for his brilliance with Art Nouveau, he himself predicted the style's own demise and that many of his works would be demolished eventually.

Important Art by Victor Horta

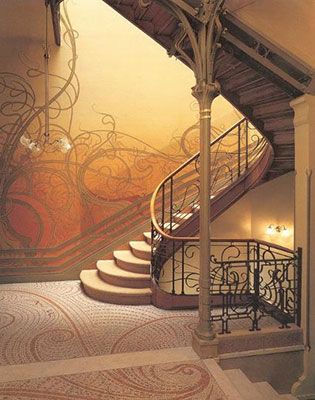

Hôtel Tassel, Brussels

The Tassel House, often cited as the first Art Nouveau building. In this townhouse for one of his typical professional clients from the 1890s - in this case, one of his colleagues at the Université Libre de Bruxelles - Horta fuses the twin themes of nature and industry almost seamlessly.

As with many of Horta's famed Art Nouveau residences, the heart of the building is the central stair hall, almost a foregone conclusion given the narrow urban lots that Horta was dealt for these commissions. Here, the emphasis is on structure, which Horta makes frankly clear in the dull green iron columns that anchor the space. The thin posts blossom into a tangle of tendrils and vine-like twists at their crown, which then blend with the vines evident in the mosaic floor and the stenciled whiplash curves of the plants on the wall surfaces. They are further echoed in the forms of the chandeliers that descend from the ceiling with flower-petal-shaped shades. The effect is that the exterior natural world (largely excluded from the tight-knit urban fabric of Brussels) is now permanently brought inside, with the soothing hues of green, orange, and yellow providing a respite from the bustling noise of the street.

The stair hall is plainly visible on the exterior, with a riveted green iron I-beam serving as its foundation above the recessed main entrance before blossoming into a luminous set of stained glass windows containing the blues of water and pinks of flowering plants. In this way Horta creates a subtle play between nature and industry, with each complementing each other as essential components of the building.

Stone, glass, iron, wood

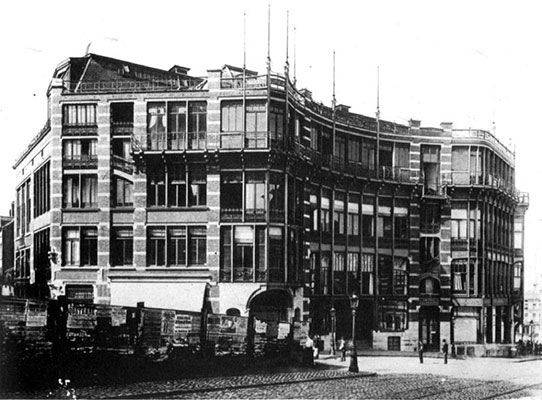

Maison du Peuple, Brussels

The crowning achievement of Horta's career was the Maison du Peuple (House of the People) in Brussels, the new headquarters of the Belgian Workers' Party. It was in many ways a temple of Socialism, as the Maison du Peuple was a common urban structure in several European countries. Maisons du Peuple provided various communal functions that often catered to working-class citizens: libraries, cafes, recreational spaces, bakeries, clothing shops, and a large auditorium for assemblies, along with offices for the local Socialist parties. Thus Horta's structure, the national headquarters for the party that represented the interests of a large sector of the population in highly industrialized Belgium, can arguably be seen as the apotheosis of the building type.

The Maison du Peuple was a masterwork of design on several levels. In the first place, Horta had to fit the building into a highly irregular wedge-shaped site that occupied about a third of the side of a circular plaza. It was organized in a way that showed the progression from pedestrian activity on the ground floor (shops, food services), towards the offices of the Party and recreational spaces such as the library on the floors above, with the auditorium, the great assembly space for discussion, lectures, performances, and cultural and political enrichment on a mass scale, at the top. On the roofline, the building was emblazoned with signs bearing the names of individuals who had contributed to the Socialist cause, such as Karl Marx and Leon Blum. Aesthetically, it was a paean to industrial methods of construction: its iron frame was clearly visible everywhere on the interior and exterior, punctuated by rivets, with an interlaced network of iron beams forming the decoration on its ceilings. The infill consisted of either the pedestrian material of red brick or glass, reflecting a transparency of purpose.

The inauguration of Horta's building in 1899 was front-page news in Brussels, with lavish posters being printed to advertise the event and the great French Socialist leader Jean Jaurès in attendance. Even in its demise some 65 years later, the Maison du Peuple highlighted the contemporary discourse about modern architecture, as it only was demolished amid massive global protests. Its replacement by a massive, aesthetically soulless concrete skyscraper has often been cited as one of the worst results of the modern redevelopment of Brussels in the 1950s and '60s that proved disastrous for Art Nouveau.

Iron, glass, stone, wood

Hôtel Van Eetvelde, Brussels

The van Eetvelde House represents arguably the most daring and innovative of Horta's residences in Brussels, built in two primary stages; the initial one from 1895-98 and an extension constructed from 1899-1901. As in the Solvay House, Horta was given an immense amount of freedom in design, in this case, for Léopold II's minister for Congolese affairs. While the facade of the house discloses a kind of rationalist, industrial structure, consisting of an iron frame with large windows, adorned with the whiplash curves that had become Horta's trademark.

Similar to the Tassel House, the significance of the building lies in its octagonal stair-hall at the center of the initial structure, whose metallic columns frankly reveal the unusual industrial frame of the residence. They branch out into flattened arches that support a large blue-green stained-glass ceiling, whose lower portions over the staircase employ Horta's exuberant, twisted curves that continue down into the balustrades and the rugs below, the furniture, and the grain of the marble around the inner walls under the stairs). Whether intentional or not, the effect suggests the modulation of light and shade and the tangles of vines and leafy foliage in the jungles of the Congo, the colonial territory that van Eetvelde administered.

More directly, the combination of the spiral of the staircase and the web-like decor implies that the residents of the house are firmly enfolded within nature's grasp. These motifs are extended throughout the furnishings of the rest of the house - in pieces as diverse as the fireplace and the lighting fixtures - emblematic of how the residence comprises a total, seamless work of art that acts like a lush oasis from the urban environment. Horta thus arguably exploits and appropriates the natural imagery of the Congo for the pleasure of his patron, though with much less sinister undertones than the way his patron's administration of the Congo - King Léopold II's personal fiefdom - exploited its native residents to near-genocidal proportions for the profitable harvest of natural resources.

Iron, glass, stone, wood

Horta House and Studio, Brussels

Horta's own house and studio are now home to the Horta Museum and constitute an important example of his surviving work. Its significance lies primarily in the way that it acts as a superb piece of rationalist architecture, expertly communicating its function and serving as an advertisement for Horta's own forward-looking architectural practice.

At ground level, the house catches the viewer's attention with the sinuous curves of Horta's signature ironwork and the I-beam used as a lintel over the double window left of the main entry, hinting at the house's industrial methods of construction. This subtle move is brought to full fruition on the interior with the frank exposure of the iron frame, particularly in the dining room, where Horta has unusually chosen the industrial material of white glazed ceramic subway tile to cover all the surfaces of the walls and ceiling. When the viewer looks upward from the street, she is immediately struck by the demonstration of the remarkable tensile and structural properties of iron, Horta's signature material: a delicate iron balcony whose posts extend upwards into sinuous corbels that astonishingly supports an entire stone oriel that bulges outward into space from the plane of the facade, thereby suggesting both Horta's own daring and genius as a designer.

Finally, once the viewer glances over to the right of the projecting bay, he notices the huge curtain wall topped by a skylight that signals a studio, indicating that the inhabitant is himself the residence's designer, whose perch on the top floor suggests he is fully in command of his craft. Inside, this sense of exclusivity can be seen in the spiraling staircase that terminates at the top in a brilliant tangle of sinuous metal structure under a skylight of white-and-gold-colored glass. Having climbed the trunk of a tree and finally reached the canopy, it is as if one now sits ensconced amongst its leafy branches and shielded from the bustle of activity on the levels below.

Stone, iron, glass, wood

Chair for the Hôtel Aubecq, Brussels

Horta frequently designed all of the aspects of his buildings, including large amounts of furniture, and was a talented interior designer. The press praised his dining room ensembles shown at the 1902 First International Exposition of Modern Decorative Art in Turin, where Art Nouveau was featured nearly to the exclusion of all other styles.

The Aubecq House (since demolished) was one of Horta's residences to feature furniture designed by him. This chair is typical of his designs from the turn of the century, with the crown of the back that flares outward and a frame that entirely eschews straight lines. The thick structure of the chair and the sinuous curves exude a sense of natural energy whose forms seem to be held in tension, kept in check by the counter-push of the other members. They mirror the whiplash curves of Horta's architectural elements that likewise convey a sense of living, stretching energy, which is underscored by the warmly-colored ash. Alternatively, one could read the bulging forms of the back and arms like the abstracted outlines of petals of a flower in full bloom, opened to receive the seated human form, thus also complementing the ubiquitous plantlike imagery of Horta's interiors that seem to enfold the residents of his houses in nature's grasp.

Ash, wicker - Brussels, Musée Fin-de-Siècle Museum

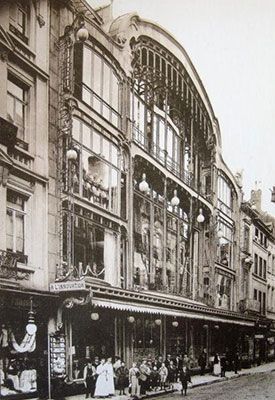

L'Innovation Department Store, Brussels

Horta was commissioned to design several department stores during his career; virtually all of them were built in a very short period between 1901 and 1906. The branch of L'Innovation that he constructed in Brussels at 111 Nieuwstraat is the best-known and most innovative of these. In it, Horta pushed the skeletal, tensile metal structure to the limits of its capabilities, exposing it to the elements with the simple infill of glass panels on the facade. The result is that the entire facade functions as one massive shop window, allowing everyone outside to see in, and vice versa.

In addition to creating a massive advertising display of the store's wares inside, the full glass facade - which stands out among the conventional stone-fronted buildings around it - communicates a sense of transparency and honesty to potential consumers, as if the store has nothing to hide. This sense of honesty is further communicated by the seamless, light use of iron for the interior structures of gallery levels around a central atrium, thus allowing customers and employees alike to survey nearly the entire store while inside. On the other hand, the building appears like a massive, glittering jewel box, with the added light from the all-glass facade adding an aura of brilliance to the items for sale inside, as if they were wrapped in a gleaming package, thus magnifying their appeal beyond their mere usefulness as ordinary commodities.

Unfortunately, in later years renovations to the store covered Horta's original curtain wall of glass with opaque panels, and the building eventually burned to the ground in a spectacular fire that took the lives of 322 people in May 1967; it was demolished shortly after.

Iron, glass

Palais des Beaux-Arts (Center for Fine Arts), Brussels

The Palais des Beaux-Arts, often fondly called "Bozar," a play on the pronunciation of the last half of its French name, demonstrates Horta's conversion from Art Nouveau to Art Deco as the latter garnered followers as a modern version of classicism in the years following World War I. It is a large complex that serves several different functions, and not surprisingly it took nearly ten years to complete.

Horta worked on an irregular, sloping site, whose ground was generally sandy and wet, and was subject to several constraints. Most notably, he could not build more than three stories, in order to preserve the view from the Royal Palace towards the center of Brussels; and he had to create street facades that allowed for the insertion of individual shops, a feature he considered unworthy of a structure called a "palace." Horta in part solved the height problem by locating many of the required spaces underground. The exterior is characterized by the interplay of cubic and rectilinear volumes in repetitive bays on the street facades, punctuated by a circular entrance pavilion distinguished by massive, severe paired Doric columns that extend the height of the upper two stories.

The interior at ground level is organized along a wide corridor that extends parallel to one facade and terminates in a grand auditorium that seats 2,200 people and serves as the home for the National Orchestra of Belgium. The building also contains several other small theaters and performance spaces, a sculpture hall (now named after Horta), exposition galleries for the visual arts, and a cinema.

Stone, steel, glass

Brussels-Central Railway Station

Horta was awarded the commission for Brussels' new central railway station in 1910, but delays caused by the two World Wars, logistical problems caused by track access, and funding constraints meant that Horta would not live to see the completion of the structure, which his student Maxine Brunfaut saw through at last in 1952. The greater part of the design was worked out by Horta in the 1930s. Part of the biggest challenge before Horta could begin designing the structure was the determination of where the heavy rail lines that would connect Brussels North and South stations - until the 1950s the twin termini of all intercity trains - would run through the center of the city.

Horta again dealt with a difficult, irregularly shaped, and sloping site. His solution was to construct a lozenge-shaped building, with one long facade that fronted the Cantersteen, with a street-level overhang to welcome passengers arriving by car. The opposite side facing the Carrefour d'Europe, which extends one level below the street grade, employs a large concave facade whose upper levels are distinguished by a multistory curtain wall. Each of the entrances from the two facades leads into the large, monumental central concourse that branches off to the intercity train platforms and subway station below ground. Horta has designed the Cantersteen facade in an unbroken rhythm of repetitive bays with minimal ornamentation, while the corners of the station use a gentle curve that makes the building's form resemble the image of a streamlined train.

Today, however, the station is undergoing studies for how to best handle the massive passenger traffic it receives - though not even designed to handle 70,000 users daily, on some days it welcomes upwards of 150,000 passengers - and so its future configuration remains uncertain.

Concrete, stone, steel

Biography of Victor Horta

Childhood and Training

Victor Horta was born in Ghent on 6 January 1861 into a large family. His father, Pierre Horta, was a luxury shoemaker, who, according to Victor, "ran his studio with such an air of superiority that for him it became an art." Victor was attracted to music at a young age, learning to play the violin. It appeared to be one of the very few things he was passionate about; nonetheless, at age 12 he was first attracted to architecture when he helped his uncle on a building site.

Horta matriculated to the local Académie des Beaux-Arts in Ghent, then left for Paris in 1878 to work in the atelier of the architect and interior decorator Jules Dubuysson in Montmartre, returning to Ghent two years later upon the death of his father. There in 1881 he married Pauline Heyse, and then moved to Brussels, where he enrolled at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts, the national art school. He also met the aspiring architect Paul Hankar, who during the 1890s would become one of his better-known colleagues in Belgium to work in Art Nouveau.

Horta did well at the Académie; in 1884 he won the inaugural Godecharle Prize for architecture, which still exists to promote the careers of young Belgian sculptors, painters, and architects, specifically to further their education and training. Around the same time he was taken on as an assistant by his professor Alphonse Balat, who was the architect to the Belgian king Léopold II. Horta was thrilled by this opportunity, as he had aspired to work with Balat for a long time. Balat was then in the midst of designing for Léopold the Royal Greenhouses at Laeken, a commodious expanse of iron-and-glass domed structures on the grounds of the royal palace (to which Balat had earlier made additions and renovations). Though not particularly inventive in terms of technology or form, the structure of the greenhouses nonetheless discloses the almost-purely-functional use of industrial materials that Horta would develop extensively thereafter.

Early Career

Balat's mentoring paid off for Horta. By 1885, he had joined the Société Centrale de l'Architecture Belge (Central Society of Belgian Architecture), established his own independent practice, and built three houses at 45-47 Twwaalfkameren Street in Ghent, his only structures in his native city. Through his mentor's influence he was awarded the commission for a small pavilion in 1889 to house a sculpture by Jef Lambeux in the Parc du Cinquantenaire in Brussels, which still stands. In 1890, his daughter Sophie was born, to whom Horta grew so strongly attached that he received custody of her when he divorced his first wife in 1906. (Their first daughter Marguerite died very young - only a few months old).

Horta socialized widely, and in 1888 he joined the Masonic lodge Les Amis Philanthropes of the Grand Orient of Belgium in Brussels, which brought him into contact with a large number of potential future clients. He was also appointed Head of Graphic Design for Architecture at the Université Libre de Bruxelles in 1892, then a professor of Architecture the following year.

Art Nouveau and the Development of a Personal Style

Horta's fellow masons Eugene Autrique and Emile Tassel (who was also a professor like Horta at the Université Libre de Bruxelles) soon commissioned him to design residences for them. These two houses, finished in 1893, represent Horta's first works in Art Nouveau - the Tassel House is often cited as the first Art Nouveau building. Horta later recalled that his goal in these two buildings was "to create a personal style, in which could be found a constructive, architectural, and social rationalism. In the Tassel House one sees for the first time the flowering of the style in full force, where Horta fuses seamlessly the structure of iron and twists it into decoration, making it resemble the shapes of vines and tendrils. This is mirrored by the decoration of the mosaic floors, the curves of the chandeliers and balustrades, and the snaking stenciled plant forms of the home's great stair hall.

It was also through Tassel that Horta met the engineer Charles Lefebure, who happened to be the secretary to Ernest Solvay, the chemist and king of industrial soda, used in various applications, including the production of glass, metallurgy, and detergents. Solvay's son Armand confided to Horta the commission for a lavish town house on the Avenue Louise in the Ixelles section of Brussels, giving the architect virtually carte blanche, and Horta obliged. He designed every facet of the house, down to the knobs, carpets, and doorbells, using expensive onyx, marble, bronze, and exotic woods, and collaborated with the painter Theo van Rysselberghe on the design of the grand staircase. The result is the Hotel Solvay, built from 1894-98, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site along with the Tassel House, the van Eetvelde House, and Horta's own house and studio. The Tassel House's use of audacious, 'whiplash' natural forms that became the hallmark of Horta's strain of Art Nouveau brought the architect instant renown, and he received a bevy of commissions in the last half of the 1890s, from various clients.

1895 was a banner year for Horta's practice. That year the city of Brussels commissioned him to build a kindergarten on the rue Saint-Ghislain. The same year, he was approached by the leaders of the Belgian Workers' Party (Parti Ouvrier Belge) to build them their new headquarters not far away. Though in his memoirs Horta insisted on his distance from politics, he had nonetheless taught an art class at the Party's old headquarters and was good friends with its intellectual leaders, including Max Hallet, Leon Furnemont and Emile Vandervelde. Horta accepted the challenge.

The result was his masterwork, the Maison du Peuple, a multifunctional structure of iron, glass, and brick that combined the Party's offices, stores, a cafe, recreational spaces, a library, and a large auditorium, all fitted into a highly irregular site on a circular plaza and on a slope. Horta supposedly made 8,500 square meters of drawings and fifteen craftsman worked for eighteen months on the ironwork. The building was finally inaugurated on Easter, in 1899, in the presence of the great French socialist leader Jean Jaurès. Brussels newspapers presented the event with great fanfare, even printing Horta's portrait among their coverage. After World War II the Belgian Workers' Party merged with other leftist organizations to form the Belgian Socialist Party, and vacated the Maison du Peuple. Amidst massive international outcry, the building was demolished in 1965, though a few remnants have been saved, and can be seen in a Brussels subway station and the Horta Museum. Its destruction and replacement by a soulless concrete skyscraper have since been described by some critics as the "greatest architectural crime" of the 20th century.

Also in 1895, Léopold II's secretary for the affairs of the Congo, Edmond van Eetvelde, commissioned Horta to build him a new residence in the fashionable district of the Avenue Palmerston. The house, which was built in two stages (the second from 1899-1901, after van Eetvelde was made a baron by Léopold), is often called Horta's most daring residential design, with the interior organized around a central octagonal stair-hall resting on iron pillars and topped by a stained glass skylight. Van Eetvelde also got Horta the job to design a pavilion of the Congo at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, though the contracts for this project were cancelled and only the drawings survive.

With this burst of success, between 1895-98 Horta purchased a couple of lots in the Saint-Gilles district of Brussels, not far from where he had built many of his residences in the 1890s and erected his own house and studio, which, thanks to the efforts of his student Jean Delhaye, now functions as the Horta Museum.

In 1897, Horta exhibited several of his designs for furniture and decor at the salon of the avant-garde artists' group La Libre Esthetique, thereby introducing his skill as an interior designer to an even wider public. That same year he was also commissioned by the Solvay family to build them a country chateau in Chambley, in northeastern France near Nancy, a kind of combination of Gothic revival and Art Nouveau design; unfortunately, the house's location near the front during World War I exposed it to bombardment and it was demolished soon after.

The New Century

Horta's career continued to flourish as the 20th century was born. While continuing to receive residential commissions in Brussels, such as the Aubecq House (1899), the Roger and Dubois Houses (1901), and a house for socialist leader Max Hallet (1902), Horta also was asked to design several department stores, such as the Grand Bazar d'Anspach in Brussels and Frankfurt, Germany (1903), the Waucquez department store in Brussels (1906), and three branches of L'Innovation in Brussels and Antwerp (1901, 1903, and 1906). In one of the two Brussels stores, Horta reached the apogee of his Art Nouveau work, employing a steel framework filled only by glass panels, thus creating a fully transparent, modern facade that functioned as a giant shop window. His work also was one of the prime attractions at the First International Exposition of Modern Decorative Art in Turin, Italy, in 1902, a fair which represented the apex of Art Nouveau's popularity in Europe.

In 1906, Horta divorced his first wife (he would remarry, to Julia Carlsson, two years later). That same year he began work on a large complex of structures for the Brugmann University Hospital in Laeken, not far from the Royal Palace, which spread out over a large number of low-rise pavilions, separated by function. The campus buildings, which cover 44 acres, use a striking combination of red and white brick. They show the stiffening and simplification of Horta's Art Nouveau, and appear much more workmanlike and sober than the exuberant, energetic designs for his more famous earlier buildings. Construction on the large project started only in 1911, was interrupted by World War I, and was only finished in 1923. It is still in use as a hospital today, and its design was positively received among the European medical community. In 1907, he designed a new Museum of Fine Arts in Tournai, Belgium, although it did not open until 1928. In 1910, Horta also received the commission for the planned new Brussels-Central Railway Station, though the work would not be completed until 1952, five years after Horta's death.

Horta resigned from his professorship at the Université Libre de Bruxelles in 1911 when the university administration did not offer him the contract to design extensions to the school's buildings. But the following year he accepted an appointment at his alma mater, the Académie des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles, and in 1913 began a three-year term as director. He planned on revising significantly the teaching of architecture at the school, which earned him the enmity of his colleagues.

World War I and Aftermath

Horta left for London in 1915 to attend the Town Planning Conference on the Reconstruction of Belgium, organized by the International Garden Cities and Town Planning Association. Belgium had already been devastated by World War I, with the German armies committing a great cultural crime by wantonly burning a large portion of the city of Louvain, including its university library, whose collection had held many priceless medieval manuscripts. However, Horta was unable to return to Belgium, so he left Britain for the United States, where he remained for the rest of the war, giving lectures at several American universities, including Cornell, Harvard, MIT, Yale, Smith College, and Wellesley College. In 1917, he accepted an appointment as Professor of Architecture at George Washington University in Washington, DC. In the United States, Horta also encountered the skyscraper for the first time and realized definitively that the wave of building in the future would not use Art Nouveau, and he resolved once the war concluded that he would need to adjust his designs to current tastes.

Turn to Art Deco and Later Works

The war left Horta in a difficult situation. Upon his return to Belgium in 1919 he sold his house and studio. That year, however, he was commissioned to design the new Palais des Beaux-Arts (Center for Fine Arts) in Brussels, a multipurpose facility that includes a concert hall, recital hall, chamber music room, a large exhibition space, a movie theater, and lecture rooms. The building took nearly ten years to complete, and was finally inaugurated in 1928; its aesthetic demonstrates that Horta had abandoned Art Nouveau fully and instead turned to a highly geometricized, rectilinear, classicized aesthetic that reflected the development of what we now call Art Deco.

In 1925, Horta was called upon to design the Belgian pavilion at the Exposition International des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris (International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts; the 1925 World's Fair). He produced a modest, symmetrical structure of wood, plaster, and other low-cost materials, whose straightforward rectilinearity was somewhat reminiscent of a small Greek temple or aedicule. It was crowned by six statues representing the historical development of the decorative arts by Marcel Wolfers, whose family had commissioned Horta to design a jewelry shop for them in Brussels in 1909.

Though late in life Horta was occupied with very few commissions, save for the ongoing work with the Brussels-Central Railway Station, he was given several honors both at home and abroad. In 1919, he was made a member of the Order of the Crown and the following year inducted into the Order of Léopold, the two highest classes of honors awarded by the Belgian state. In 1926, he served on the jury for the competition of the new buildings for the League of Nations in Geneva, and was named a member of the French Legion of Honor. In 1932, he was named a Baron by Albert I, the Belgian king.

In 1939, Horta began work on his Mémoires, which were only published posthumously in 1985. During the Second World War, he burned most of his papers and designs, regretting that he had never made the effort to actually publish his works. Perhaps because he had never done so, Horta was mostly forgotten at the time of his death in 1947. His student Maxine Brunfaut completed his unfinished Brussels-Central Railway Station in 1952, according to Horta's own plans. Horta was interred at Ixelles Cemetery in Brussels.

The Legacy of Victor Horta

During the height of his career at the turn of the 20th century, Horta achieved international renown as an innovator. He was an especially strong influence on the French Art Nouveau architect Hector Guimard, whom Horta met once in 1894 and advised to "banish the flower" in favor of the stalk in Guimard's own explorations of style. Horta also inspired a large number of minor architects in Belgium and especially around Brussels, thereby making Art Nouveau a kind of "national style" around 1900. His 'whiplash' curves, nearly a trademark aesthetic, are often termed "the Belgian line" in architectural discourse.

Horta did not represent the complete trajectory of Art Nouveau in Belgium, however; on the other pole was Henry van de Velde, with whom Horta did not have a good relationship. Though he sometimes borrowed from Horta's curvilinear aesthetic, van de Velde was known much more to favor the Arts and Crafts, and eventually left Belgium in 1899 to become director of the Arts and Crafts school in Weimar, Germany, before being forced out at the start of World War I. Unlike Horta, van de Velde had come to architecture through painting and the decorative arts (with Horta it was the other way around, and Horta never painted, anyways). While van de Velde was a gifted and polemical writer, Horta was laconic and published very little, preferring to let his built work and designs speak for him.

Horta died during an era when Art Nouveau began to enter one of the darkest chapters of its history. He had foreseen that many of his works would likely be destroyed because of the nature of the style in many places as a passing fad. Most of his department stores have been demolished; his great branch of L'Innovation in Brussels of 1903 was remodeled and then destroyed in a fire in 1967, and most famously, the Maison du Peuple was dismantled in 1965 amid a public outcry.

Such is not the case with Horta's residential works. His students Jean Delhaye and Maxine Brunfaut did much to ensure the survival of several of Horta's key works, as did many private owners of the houses that he built in Brussels, and a great number of them still remain; some are even open to the public occasionally. Even the Waucquez Department Store in Brussels still stands, and is in large part preserved, having now been transformed into the Museum of the Comic Strip.

With the revival of scholarly attention on Art Nouveau between the 1950s and 1970s, Horta's image began to be rehabilitated. At first, much of Art Nouveau was considered to be a critical forerunner or embryonic form of the modern movement, part of the search for a style for the "machine age" as epitomized by the International Style of architecture at midcentury. But more recently, Art Nouveau has begun to be treated as a style worthy of its own scholarly treatment and Horta's image as one of the great Belgian architects has been restored. At the end of the 20th century, Horta's portrait and whiplash designs were featured on the 2000 Belgian franc note.

Railings from Horta's Maison du Peuple can now be seen in the Brussels subway station Horta (named for him). Today the Musée Horta is now located in his former house and studio, meticulously preserved, and dedicated to the cultivation of his legacy.

Influences and Connections

- Alphonse Balat

- Godefroy Devreese

- Eugene Viollet-le-Duc

- Paul Hankar

- Max Hallet

- Leon Furnemont

- Emile Tassel

- Edmond van Eetvelde

-

![Arts and Crafts Movement]() Arts and Crafts Movement

Arts and Crafts Movement - La Libre Esthetique

- Les XX

-

![Hector Guimard]() Hector Guimard

Hector Guimard - Gustave Bovy Serrurier

- Marcel Wolfers

- Philippe Wolfers

- Jean Delhaye

-

![Laurie Anderson]() Laurie Anderson

Laurie Anderson ![Charles Atlas]() Charles Atlas

Charles Atlas- Pierre Braecke