Summary of Hector Guimard

Hector Guimard practiced what he preached. His architectural creations tend to embrace each of the different branches of the arts, from painting and sculpture to graphics and even typography. The seamless harmony and flow that reigns in the aesthetic of Guimard's buildings and other works very much mirrors the kind of harmonious environment and society that Guimard hoped the world could eventually achieve politically, though this never came to pass. Guimard's version of Art Nouveau was nationalistic (he was French), but also focused on community and the friendly acknowledgement of differences between the varied nationalities and ethnicities of the world. Today Guimard is regarded as one of the most individualistic artists of his era, one of the innovating founders of Art Nouveau who developed a personal aesthetic that is often instantly recognizable and distinguishable even from his fellow practitioners of the style.

Accomplishments

- Guimard is by far the best-known French Art Nouveau architect, to the extent that in some French circles Art Nouveau was referred to as "Style Guimard," a moniker promoted by Guimard himself. His work is easy to distinguish amongst other practitioners of the style, with plastic, abstracted and sometimes bizarre vegetal and floral imagery in iron, glass, and carved stone that is usually twisted and bent into irregular and asymmetrical forms.

- Though well-educated at the École nationale des arts décoratifs, and familiar with many of the leading French architectural theorists, Guimard attended but did not receive a diploma from the École des Beaux-Arts as was the norm for most French academic architects at the end of the 19th century, and was often thought of during his lifetime as outside the mainstream of architectural practice.

- Guimard's work has recently been discovered to be rather political - particularly pacifist and socialist. The strange forms in his architecture are intended to function as great kinds of social levelers, favoring no social or economic class above any other in terms of their familiarity or ability to be interpreted. As a result, they also constitute a step towards artistic abstraction, one of the great developments of 20th-century modernism.

- Guimard's Paris Métro entrances are his signature work and classic emblems of Art Nouveau, which combine the movement's embrace of nature as well as the advances of technology, standardization, and modernization. Their sinuous, unusual forms stand out against the typical street environments, making them ideal for their functions, and they have become worldwide icons for mass transit design.

Important Art by Hector Guimard

École du Sacré Coeur (Sacred Heart School), Paris

Guimard's first significant work, the École du Sacré Coeur, an elementary education facility in the 16th arrondissement, shows the way that he uses technological innovations to improve on a classic building type in French architecture. The building exhibits the usual features of most French primary schools: the bands of yellow brick or stone punctuated by large panels of windows, often topped by shallow arched lintels of red brick, like on the upper level.

The key feature of the structure, however, is at ground level, where Guimard has used pairs of inclined iron columns arranged in a V shape (seen here) to raise all the classroom space one floor above. The scheme is directly taken from a design by Eugene-Emmanuel Viollet-le-duc for just such a school, to demonstrate the possibilities of iron structural technology. Here, Guimard has rotated the columns 90 degrees from Viollet's plan to align with the plane of the façades and thus clear the space at ground level under the rest of the structure as a playground, thus solving the problem of the limited space on the site. Much of this area at ground level, however, was enclosed in the 1950s, which eliminated this recreational function.

The columns themselves use an unusual shape that leaves them open to precise interpretations, thus attracting continual rumination and attention. They taper towards the bottom, with flared joints where they join the I-beams that support the rest of the school structure above, resembling torches that may represent the archetypal lamp of learning. The twisted grooves on the upper parts of the columns add a kind of dynamism to the shape, as if to represent the compression of force transferred through them to the ground below, much like the sinews of muscles or the plastic three-dimensional forms of stems of plants. It thus represents some of Guimard's first recognizable experiments with Art Nouveau.

Castel Beranger, Paris

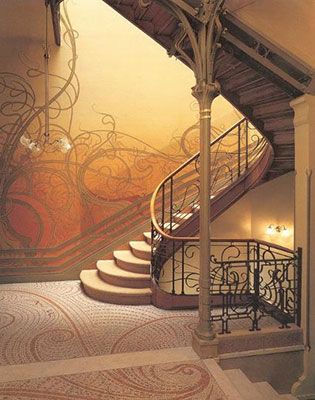

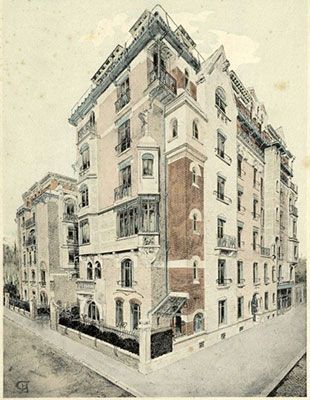

The Castel Beranger is the building that made Guimard famous, and he regarded it as one of his most important, going so far as to include it along with the Humbert de Romans concert hall and the Paris Métro entrances as some of his most notable in an article in Architectural Record explaining Art Nouveau to an American audience in 1902. It is a multistory apartment building of 36 units in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, for which Guimard was given carte blanche by his patron, Mme. Marie-Elisabeth Fournier, and was the first apartment structure in the city to use the new style. As a result, it displays the complete range of Guimard's creative powers with Art Nouveau, the full expression of which he had seen just before he started designing it when he traveled to Brussels and met Victor Horta in 1895. After the completion of the project, Guimard sent Horta a signed copy of the lavish album of prints produced to publicly promote it, along with an inscription of admiration. (The first plate from this folio, a perspective of the building - which is difficult to capture in its entirety in a photograph - is pictured here.)

The Castel Beranger's ornament is full of whiplash and undulating plastic surfaces, such as in the vestibule, whose walls are covered with glazed ceramic tile. These are seamlessly complemented by similar sinuous forms resembling the stems or branches of plants inside the individual apartments, two of which were occupied by Guimard and his friend, the painter Paul Signac. The building makes extensive use of copper sheeting and ornament in the balconies, downspouts, and gates, much of which has been oxidized to a natural green, using strange motifs such as facial masks and seahorses. Its name "Castel" suggests its comparison (especially its picturesque quality and use of rusticated stone) to a medieval castle and, by extension, the Gothic style, which Guimard admired. In 1898 it won the inaugural façade competition launched by the city of Paris to encourage new variety in design amongst the city's monotonous stretches of bourgeois apartment buildings. This distinction, now carved into the façade, catapulted Guimard to instant fame. Nonetheless, the building spawned numerous detractors who decried the curious forms of Art Nouveau, nicknaming the building the "Castel Dérangé" (Deranged Castle). It remains one of Guimard's largest surviving works.

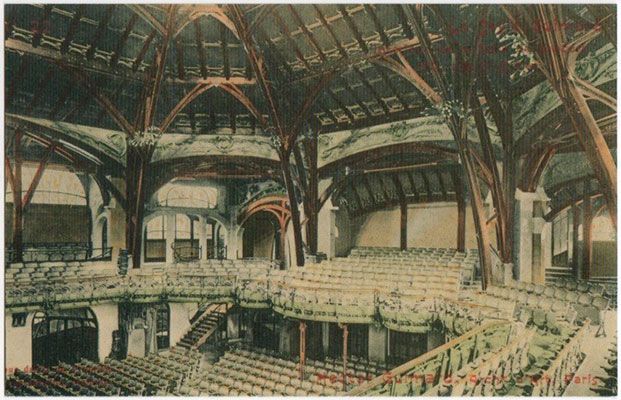

Humbert de Romans Concert Hall and School, Paris

One of the commissions that Guimard received in the wake of the success of the Castel Beranger was a combination concert hall and parochial school complex in the 16th arrondissement conceived by the Dominican monk known as Père Lavy, intended to be ready in time for the Exposition Universelle in 1900. Here again Guimard did not disappoint. The lavish building was a tour-de-force of Guimard's creative powers, with sinuous arabesques covering the surfaces and structures, creating a continuous sense of movement and animation for the visitor. The heart of the structure was the octagonal concert hall, with a vaulted roof structure of iron and abundant mahogany paneling, accented by colored glass of yellow and orange whose effect in modulating the interior natural light must have been spectacular. The auditorium, focused around a hexagonal stage with room for 100 musicians and 120 choristers, contained a massive organ. It could seat an audience of 1150 people - one of only two venues in Paris to accommodate that many spectators - on chairs designed by Guimard with a twisted, mass-produced iron frame, all painted green with luxurious embroidered cushions monogrammed "HR." Guimard even consulted noted composer Camille Saint-Saens on the hall's design, producing magnificent acoustic effects.

Sadly, the structure was doomed probably from its conception, as Père Lavy was admonished by his superiors for commissioning a building so lavish, whose purpose was viewed as suspect as it appeared to be devoted to secular rather than church functions (the building contained no noticeable religious iconography, nor except for its name did it hint at having a religious purpose). Its construction required a huge amount of expensive materials, including marble, along with the stained glass and ample quantities of mahogany, and was a financial disaster. One month after the dedication on 9 November 1901, Père Lavy left Paris, reassigned by his superiors to Constantinople. The building struggled to turn a profit as a concert venue and was sold at auction in 1904; its new owners demolished it soon after and replaced it with a tennis court.

Entrances for the Paris Métropolitain

When Guimard was commissioned to design what would become his signature work, Paris was only the second city in the world (after London) to have constructed an underground railway. Guimard's design answered the desire to celebrate and promote this new, efficient infrastructure with a bold structure that would be clearly visible on the everyday Paris streetscape. Guimard was awarded the commission as a favor from the Socialist-controlled Paris City Council, whose political leanings mirrored his own sympathies.

The Métro connects with themes of Socialism and industry on several levels. Guimard used the industrial materials of cast iron for the structures of the entrances - a nod, no doubt, to the industrial workers who used the system for their commute and helped build the network. Guimard created three standard types of entrances: enclosed, tripod canopies, and open to the sky - that use the twisted, organic vegetal forms typical of Art Nouveau. At first, these appear to be nearly seamless, yet in fact they are constructed out of several cast iron parts that were easily mass-produced at the modern iron foundries to the east of Paris. The possibilities of cast iron were shown off in two unique elaborate enclosed pavilions, located at the busy stations Bastille and Etoile, which were often nicknamed "Chinese pagodas" due to their resemblance to eastern architecture. In another modern twist, the red bulbs that illuminated many of the entrances at night also pulsated upon the arrival of a train to alert potential users at street level. Guimard even invented the typography used for the yellow porcelain signs hung between the lamps, a typeface that has now famously become known as Métropolitain.

But the Métro entrances' forms do much more than make smart use of modern technology. Guimard conceived of the Métro as a means to connect people residing in different geographic parts of the city and across social classes and backgrounds - especially since Paris has traditionally been a favorite destination for immigrants and foreign travelers. The sinuous stem, seed-pod, and bulbous forms of nature Guimard employs are unrecognizable as any particular species, in effect making them great levelers of all who use the network, as they are universally incomprehensible - save for the "M" cleverly worked into the seed-pod shields in the railings. Guimard's designs were thus instrumental in bringing Art Nouveau's otherwise complex designs to a mass audience for whom the style seemed like a symbol of unattainable luxury (a function that it arguably still fulfills today). They helped combat the notion that Art Nouveau was a style destined only for a wealthy clientele who could afford lavish and labor-intensive constructions.

For all their attempts at unity, the Métro entrances nonetheless represent one of the most noteworthy examples of the French backlash against Art Nouveau. As early as 1908, Guimard's entrances were removed from the Champs-Elysees because they did not "harmonize" with the classical buildings there. Demolition of individual entrances continued through the 1960s, with the Etoile pavilion removed in 1926 and the Bastille station in 1962. With the retrospective recognition of Guimard's artistic genius, however, the remaining 88 entrances have been protected by the French state since 1978. Moreover, the physical dissemination of Guimard's entrances to different cities across the world and their functional installation there means that his designs have become universally synonymous with the idea of mass transit. In this sense, they finally fulfill Guimard's dream of linking people across political, social and economic boundaries, on an even broader level than he may have ever imagined.

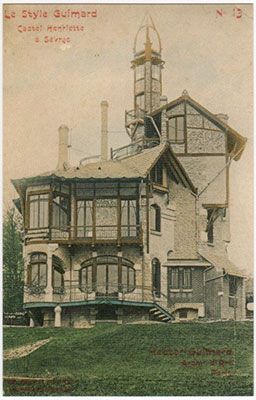

Castel Henriette, Sèvres, France

The Castel Henriette reflects the kinds of suburban or vacation houses that several of Guimard's clients commissioned from him, many of which were either located a short distance from Paris or on the seashore of the English Channel in Normandy. Often the villas were given pet names by their owners, such as "La Bluette," or "La Surprise." Guimard usually designed them with an exposed wood framework of curved members that was filled in with rusticated millstone. Each one used a highly picturesque design, asymmetrical volumes with steep gabled roofs and dormers, and sometimes, tall turrets. The "castel" designation like a castle is appropriate for many of these, as they consisted as private country retreats where their owners could escape the bustle and crowding of Parisian daily life.

In another sense, the connection with nature emphasized by Art Nouveau becomes most explicit in these houses, which appear in some cases like modest hamlets that might be carved out of rock formations instead of built, or assembled in a hodgepodge manner from whatever materials are available, not unlike the kinds of houses that Antoni Gaudí, for example, imagined for the residents of the Parc Güell at about the same time. It also gives an illusory sense of age to the structures that makes them appear much like ruined medieval buildings that are being reclaimed by the landscape, a theme that visually was associated with Romanticism. Indeed, when some of these Guimard-designed structures were abandoned their disrepair literally created such kinds of crumbling ruins; in the case of the Castel Henriette, vacated after World War II, the structure was used as a haunted house setting for several films in the 1960s; despite public outcry, it was demolished in April 1969, though several fragments were salvaged and can be located in museum collections.

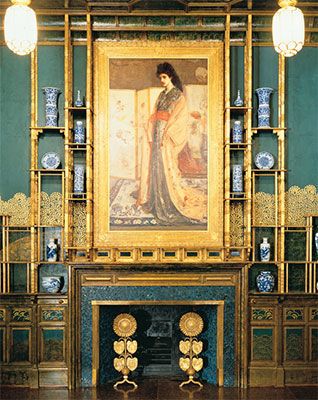

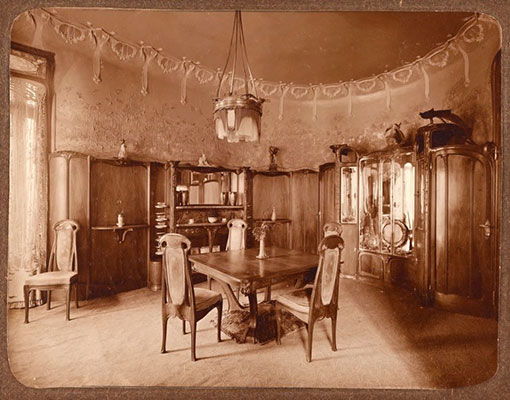

Dining Room suite for the Hôtel Guimard, Paris

Guimard, like many other architects of his era, including his contemporary Frank Lloyd Wright, had a propensity to make his buildings Gesamtkunstwerks, or total works of art, designing everything down to the tableware and napkins that his clients used. The idea was to make the aesthetic of the entire building as harmonious and seamless as possible. His own house, which he designed in 1909 as a wedding present for his wife, herself a talented painter, was no exception. Numerous examples of Guimard's furniture can be seen today in museums; Mme. Guimard donated the dining room suite from the couple's house in Paris to the city, including the cabinetry and wall panels.

As a result, Guimard's furniture, like his buildings, is usually easily recognizable due to his highly personal aesthetic. It was unusual for the exact same furniture designs to be re-used for different commissions. The chairs of this suite are nonetheless characteristic of Guimard's seating designs: they have a tall, thin back that usually terminates in ear-shaped handles at the top, with a kind of sinuous carved construction of the legs that has a very subtle curve to it. In some ways they are reminiscent of 18th-century Rococo furniture, a period which was also seen as a "golden age" of French decorative arts. The cabinetry, meanwhile, is typical of large-scale Art Nouveau storage designs, with a kind of arabesque curve to the front that undulates, bulging forward and recessing back rhythmically, in a manner that keeps the viewer's eye moving about the room, studded with floral and vegetal motifs within the structural members. One can see how the paneling, table and chairs fit nearly seamlessly with the rest of the interior, which was covered with natural relief motifs on the walls and a repetitive, elaborate molding of sinuous brackets around the ceiling line.

Petit Palais, Museum of the City of Paris

Agoudas Hakehilos Synagogue, Paris

Guimard's only religious structure is this Jewish house of worship located on the rue Pavee in the Marais, a traditionally Jewish district in the center of Paris; as such, it is often known simply as the Rue Pavee Synagogue. It was commissioned by a community of relatively recent immigrant Orthodox Jews from what is now Russia and Poland. Constructed on a very narrow lot, with little frontage on what is also a very narrow street, Guimard chose to give the structure a distinctive presence by building upward, with a predictably undulating façade capped by a roof that projects forward at the center.

The synagogue is one of Guimard's late works; in truth he built no more than five buildings after this structure was inaugurated on 7 June 1914, barely two months before the start of World War I. As such, it forecasts his move towards a stiffer, less flamboyant, and more angular aesthetic characteristic of the larger turn towards Art Deco. This is particularly evident in the main worship space, particularly in the columns and brackets. It is unknown precisely why Guimard chose to depart from his highly personal aesthetic, though cost (the synagogue was erected entirely through private funds) may well have been a factor.

The interior worship space, organized on three levels around a central nave, makes the most of a condensed footprint, arguably bringing the congregation closer together as they face one another and the service towards the back of the nave, illuminated itself by a large window. The front of the building, in fact, houses offices and educational spaces, a characteristic of Orthodox Jewish buildings signifying the congregation's wishes to engage more closely with the daily activities of the world beyond rather than cloister itself off. Such a purpose might also be read in the way that the façade is concave, as if to embrace those approaching the building.

Biography of Hector Guimard

Early Life and Education

Hector-Germain Guimard was born in Lyons in March 1867. He was the first of several major architects to be born that year, two months before Frank Lloyd Wright, four months before Henry Hornbostel, and nine before Josef Maria Olbrich. His father was an orthopedist originally from Toucy, while his mother was a seamstress from Larajasse. Guimard developed a difficult relationship with his parents: at age thirteen the family moved from Lyons to Levallois-Perret, just outside the northwestern city limits of Paris, and soon afterward Guimard apparently ran away from home, finding refuge in the home of Apollonie Grivellé, a rich landowner in the suburban 16th arrondissement of Paris.

At the age of fifteen, Guimard entered the École supérieure des arts décoratifs in Paris, the national school for decorative arts. Two of his teachers there were Charles Genuys, the official chief architect for the Commission of Historic Monuments, and Eugene Train, the official municipal architect for the city of Paris. He also received instruction from the decorative artist Victor-Marie-Charles Ruprich-Robert, who introduced Guimard to the study of nature and the intimate relationship between structure and decoration.

Genuys and Ruprich-Robert were disciples of Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, a fervent Gothicist and Genuys' predecessor as the first chief architect of historic monuments. Viollet-le-Duc greatly admired the medieval use of vaulted construction and dreamed about using the modern material of iron to achieve similar results. Viollet-le-Duc was in charge of restoring many medieval buildings that had either been intentionally damaged or fallen into disrepair over the subsequent centuries, sometimes "over-restoring" them to a kind of idealized state that had not previously existed, for which he has received substantial criticism from many purists (the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris is probably the best example). It is undoubtedly due to this lineage from Viollet-le-duc that Guimard developed his own great love of exposed, honest, and experimental structure in his buildings.

The young Guimard proved adept artistically and excelled at the École nationale des arts décoratifs; in 1884 his designs were awarded two silver and three bronze medals. The following year, he placed in every competition he entered, winning four bronze medals, five silver, and the school's most prestigious award, the Grand Prix d'Architecture known as the Prix Jay.

Guimard then enrolled in the architecture section of the École nationale des Beaux-Arts, then the foremost architecture school in the world, through which most French architects passed and which featured a global student body, with a growing number of American and central and eastern European students by the late 1880s. There he joined the atelier of the architect Gustave Raulin, who had inherited it in 1881 from the even-more influential Emile Vaudremer, who still retained an active role in it as a teacher.

In a much more competitive architectural environment than the École des arts décoratifs, Guimard's brilliance did not shine through quite as clearly. He entered the 1892 competition for the Prix de Rome, the École des Beaux-Arts' most prestigious prize, which carried a five-year stipend to study at the French Academy in Rome, but was eliminated early on. This was not necessarily a mark of failure: one of the mottoes of the Raulin-Vaudremer atelier was to "let everyone develop according to his own tastes and aptitudes" - a quality that would be clearly borne out with Guimard's work. Nonetheless, Guimard made friends with many of his comrades, including Henri Sauvage, who like him would become one of the pioneers of Art Nouveau in France in the 1890s. He also won a small travel scholarship in 1894, which allowed him to go to England and visit many Arts and Crafts and Aesthetic movement buildings, interiors, and craft workshops.

Early Career

Guimard chose to begin independent practice in 1888, with a small commission for an outdoor cafe and stage on the quai d'Auteuil, on the banks of the Seine in his home neighborhood of the 16th arrondissement. The following year he was given the job of constructing Ferdinand de Boyères electrotherapy exhibit at the Exposition Universelle in Paris.

Guimard also helped support himself by teaching. In 1891, he became a professor of drawing for the girls' section at his alma mater, the École des arts décoratifs, being promoted twice, in 1892 and 1894. He remained a professor there until leaving in 1900, after his career had reached new heights. Despite the fact that most of his students were women, he remained a bachelor for the next fifteen years.

During the early 1890s, Guimard's career began to gather steam as the 16th arrondissement of Paris was rapidly developing into a fashionable suburban district. Guimard was asked to design several single-family houses and large apartment buildings in the neighborhood by developers and landowners who recognized its potential. As someone who grew up in that arrondissement, Guimard knew the area well and likewise understood what his clients wanted. These commissions in effect launched his career.

It was also during the mid-1890s that Guimard met and befriended several colleagues who would collaborate with him on a number of projects over the mature part of his career. One of the first was Louis Muller, a ceramicist who produced the lettering designed by Guimard for the house at 142, avenue de Versailles, in Paris. Guimard also met Alexandre Bigot, another prominent ceramicist who developed an extensive network of contacts with architects who would soon be working in the new style appropriately called Art Nouveau, including Jules Lavirotte, with whom Bigot would collaborate on a large apartment house in Paris' 7th arrondissement.

In 1894, Guimard met the Belgian architect Paul Hankar, who had recently completed his own townhouse, one of the first examples of Art Nouveau, in Brussels. The following year, Guimard traveled to Brussels and met Victor Horta, with whom he would develop a close correspondence and for whom he expressed great admiration. Guimard was greatly moved when he visited Horta's Hotel Tassel, completed two years earlier and often considered the first Art Nouveau building. Like Guimard, Horta was looking to nature as inspiration for a modern architecture, and he told Guimard that he preferred, when looking at a plant, to cut off the flower and concentrate on the stem, the essential structure.

The Development of Art Nouveau

Guimard's artistic contacts also brought him into the circles of several bourgeois and upper-class patrons, including Anne-Elisabeth Fournier, a wealthy widow who also lived in the 16th arrondissement. Fournier and the architect hit it off, and by the end of 1894 she had given Guimard the commission to build a new speculative apartment house on the rue de la Fontaine, soon to be called the Castel Beranger. When Guimard returned from Belgium and the Netherlands after his inspirational meeting with Horta in the summer of 1895, he persuaded Fournier to let him design the building using Art Nouveau. Fournier gave Guimard essentially carte blanche for the job, and he did not disappoint. Guimard himself moved into one of the apartments, relocating his studio there as well. One of his neighbors in the building and friends was the painter Paul Signac. Guimard would later publicize his own practice on a series of postcards that not only showed his completed buildings but also an image of him working in the studio, which reveals the seamless style of Art Nouveau that he had clearly mastered with ease in a very short time.

Because Guimard was not a graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts, he did not benefit from the connections and alumni network that a diploma from the institution offered. Instead he relied upon a relatively small circle group of artistically adventurous, loyal clients who provided him the opportunity to cultivate his art. For example, for the Nozal family, Guimard not only built a house in the 16th arrondissement in Paris, but also artists' studios, a country house in Normandy, and the new steel and ceramics factories just north of Paris.

Guimard seemed to relish this relative isolation, however, because it made him more distinctive and individualistic. In 1903, he released a series of postcards advertising his work, almost all of which bore in red script the moniker "Architecte d'art," suggesting that he was truly an imaginative designer, not simply a constructor like other architects. He also inextricably tied himself to Art Nouveau as a style, as the postcard in the series of him working in his atelier attests by the phrase "Le Style Guimard," and in some circles indeed Art Nouveau literally became known by that name.

The years between 1895 and 1905 were the most productive for Guimard. It was during this period that his best-known works were constructed. Guimard designed and built schools, funerary monuments, apartment houses, town houses, vacation homes and country villas, a concert hall, train stations, ceramics factories, artist studios, and exposition pavilions. During this decade Art Nouveau reached the apogee of its popularity in Paris and then began to recede.

In 1909, Guimard married the American painter Adeline Oppenheim, who had trained in France during much of the previous decade; his wedding present to her was a new house Hector designed on the Avenue Mozart in the 16th arrondissement of Paris. The house still stands today, though the interiors do not retain the full range of Guimard's designs, most notably the original furniture, which the Guimards took with them when they moved to New York in 1938. Mme. Guimard later donated the dining room suite and interior wall paneling to the city of Paris in the late 1940s. It is on display today at the Petit Palais.

Social Activism

Guimard had a deep social consciousness. He joined the new Ligue des Droits de l'Homme (League of the Rights of Man), an organization that fought against injustice, soon after it was founded in 1898, and like its members Emile Gallé and Victor Prouvé of Nancy, he became a supporter of Alfred Dreyfus and the campaign to overturn the disgraced captain's wrongful conviction. The Ligue also fought for workers on the construction of the 1900 Exposition Universelle, whose employers were cheating them out of the wages mandated to them by the state.

Like many of his fellow members of the Ligue, Guimard recognized the catastrophic consequences of the arms race that was developing out of the complex system of alliances and nationalist sentiments in Europe. After World War I broke out, Guimard published a couple of pamphlets arguing for the wholesale disarmament of nations and the establishment of an international body in Europe that would prevent armed conflict (essentially a forerunner to the League of Nations), along with an international tribunal. He joined a committee formed in 1917 called Etat-Pax (Peace State), headed by Adolphe Carnot (the brother of Sadi Carnot, an assassinated President of France) that advocated for the formation of precisely these organizations.

Late Career

After 1909 the number of Guimard's commissions dropped precipitously. This was due for certain to several factors, chief among them the decline in Art Nouveau's popularity - it had long fought charges that it was a foreign import from Belgium or Germany, despite the fact that at the dawn of the century it had been suggested as the basis for a French "national style." Guimard's own difficult personality - which likely was one reason why he never developed a loyal following - must have also contributed to his dwindling clientele. In all likelihood, Guimard also probably did not feel obligated to continue to seek out a steady stream of commissions since his wife was independently wealthy.

During World War I, when building activity came virtually to a standstill, Guimard left Paris, living in Candes Saint-Martin and Pau in the west and far southwest of the country, respectively, far from the fighting. The interwar period became known for the emergence of the style known now as Art Deco, which took its name from the 1925 Exposition International des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris, where it predominated. Guimard was awarded the right to design the church for the French Village at the fair, which shows a stiff, angular form that is only an echo of his work from the turn of the century. He built his last realized work in 1930. Guimard retained a strong bond with a small circle of friends, giving the eulogy at Henri Sauvage's funeral when the latter passed in 1932.

The Legacy of Hector Guimard

Guimard's wife Adeline was of Jewish descent, and with the growing Nazi menace in the late 1930s and the German antipathy towards modern art as showcased in the Degenerate Art exhibition that opened in Munich in 1937, the two felt unsafe and immigrated to New York in 1938; Hector died there four years later.

In the aftermath of World War II, Adeline, who outlived Hector by 23 years, returned to France to settle her late husband's affairs. She attempted to convince French officials to establish a museum dedicated to Guimard's legacy. Rebuffed, however, she donated the remaining original furniture in her possession to several Parisian and Lyonnais museums, then placed much of Guimard's extant drawings, correspondence, and other archival materials with the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the New York Public Library, where they now reside.

Guimard's decision to tie himself to one particular style served him well briefly, but by the close of World War II he was largely forgotten. The 1950s and '60s proved a catastrophic period for Art Nouveau and particularly Guimard's own work. A few of his most elaborate Parisian subway entrances, for example, had been destroyed long before the Second World War, but their removal accelerated in a climate of increasing modernization of the Métro and changing tastes in favor of the International Style. The most notable of these demolitions in the postwar period was that of the elaborate "Chinese pavilion" Bastille station, one of the centerpieces of the network, in 1962. Guimard's buildings use a highly personal style that suited the tastes of his initial clients; as they changed hands, many of their new owners sought to transform them as they saw fit, often beyond recognition, and in some cases bulldozing or dismantling them. Other private houses by Guimard in the always-highly-fashionable 16th arrondissement were demolished to make way for speculative modern apartment buildings. Few took notice in 1967 when the centennial of Guimard's birth came and went.

At the same time, however, Art Nouveau and especially Guimard slowly began to experience a revival, beginning in the scholarly literature in the 1950s. Several museum exhibitions in Europe and North America during the 1970s began to rehabilitate the reputation of Guimard and many of his fellow Art Nouveau designers. The beginnings of the preservation movement now actively sought to prevent the further destruction or alteration of Guimard's works. In 1992, the 125th anniversary of his birth, the Musée d'Orsay devoted a large show solely to Guimard and some of the first monographs devoted solely to the architect appeared that decade. The year 2000 saw a flood of publications commemorating 100 years since 1900 and that year's world's fair in Paris, and, by extension, Art Nouveau.

Many of Guimard's buildings, including the 88 remaining Art Nouveau Paris Métro entrances designed by him, have now been classified as French historic monuments (in 1913 there were supposedly 167 entrances in place). In the spirit of cultural exchange, over the last half of the 20th century the Régie autonome des transports parisiens (RATP), which runs the Métro, has given several replicas of Guimard's original Métro entrances to various cities around the world, such as Lisbon, Moscow, and Chicago. The most notable of these entrances are those in Montréal, given in 1967, and in Mexico City, gifted in 1968, when each of those cities' subway systems opened (the RATP assisted with the construction of the network in Mexico). In return, each time the RATP has received works of art by major artists from the country receiving the Guimard replica. Additionally, several Guimard Métro entrances can be found in major museums with strong collections of decorative arts, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, and the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio. A street in the 19th arrondissement of Paris has been named the rue Hector-Guimard since 1984. Online, a society known as Le Cercle Guimard, made up mostly of Art Nouveau enthusiasts in France, actively promotes his legacy.

Influences and Connections

- Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc

- Victor-Marie-Charles Ruprich-Robert

- Charles Genuys

- Gustave Raulin

- Emile Vaudremer

-

![Victor Horta]() Victor Horta

Victor Horta - Alexandre Bigot

- Paul Hankar

-

![Art Nouveau]() Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau -

![Baroque Art and Architecture]() Baroque Art and Architecture

Baroque Art and Architecture -

![The Rococo]() The Rococo

The Rococo ![Gothic Revival]() Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival

- Eugène Vallin

- Emile André

- Louis Majorelle

- Louis Trézel

- Alexandre Charpentier

-

![Paul Signac]() Paul Signac

Paul Signac - Henri Sauvage

- Frantz Jourdain

- Charles Plumet

Useful Resources on Hector Guimard

- Architectural Monographs 2: Hector Guimard (1978)Our PickImage based survey of the French architect's projects and designs

- Hector Guimard (1988)Our PickMonograph of Hector Guimard works

- Hector Guimard (1970)MOMA 1970 catalogue / supplemental materials

- Guimard: Paris, Musée d'Orsay, 13 avril-26 juillet 1992 [et] Lyon, Musée des arts décoratifs et des tissus, 25 septembre 1992-3 janvier 1993 (1992)

- Guimard: Colloque international, Musée d'Orsay, 12 et 13 juin 1992 (1994)