Summary of The Wiener Werkstätte

The Wiener Werkstätte (Viennese Workshops) was one of the longest-lived design movements of the twentieth century and a key organization for the development of modernism. Centered in the Austrian capital, it stood at the doorway between traditional methods of manufacture and a distinctly avant-garde aesthetic. The Wiener Werkstätte's emphasis on complete artistic freedom resulted in a prodigious output of designs, and this, along with an army of skilled craftsmen and a complex network of production and distribution made it the standard for Austrian design between the dawn of the century and the depths of the Great Depression. Led by the unassuming architect Josef Hoffmann and his associates such as Dagobert Peche and Koloman Moser, the Wiener Werkstätte drew from movements such as the Arts & Crafts and Art Nouveau as well as from traditional folk art, and forecasted the flowering of Art Deco and the International Style in the interwar period. Its demise in the midst of repeated financial crises demonstrates the ultimate inability of artistic enterprises to completely free themselves from the economic concerns of the age.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The Wiener Werkstätte was the first organization in Austria dedicated to the production of modern decorative arts. Together with the Vienna Secession, out of which it was formed, it broke away from the stylistic revivals that had dominated Austrian architecture and design during the 19th century, though eventually it returned to historical tropes when new designers joined the group in the 1910s.

- The Wiener Werkstätte initially emphasized the creation of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or "total work of art," that sought to create a unified aesthetic across an entire designed environment, though this effort eventually fragmented into a highly diverse set of fields, with less and less emphasis on architecture and large-scale interiors, largely due to the financial constraints of the group's clients.

- The Wiener Werkstätte innovatively envisioned that many of its activities would complement and promote each other - for example, its postcards often featured the Workshops' output in architecture, textiles, fashion, and glass and ceramics - a move that helped Werkstätte attain two of its goals: first, narrowing the gap in prestige between artistic genres; and second, bolstering the commercial visibility of its designs.

- Unlike other contemporaneous movements in the decorative arts and design, the Wiener Werkstätte did not seek to create an art that would be accessible to all and enlighten the masses; instead, the group focused on the highest quality craftsmanship and materials for a socioeconomic elite that, perhaps ironically, would treat its work more as art objects than utilitarian items.

- Translated as the "Viennese Workshops," the name Wiener Werkstätte represents well the nature of its organization: it incorporated the craft-based production of decorative arts in a mostly rural country, which was historically concentrated in its primary metropolis. Though its artists made ample use of new industrial materials, they resisted temptations to completely turn to mass production.

- The artistry of the Wiener Werkstätte always took primacy over the commercial bottom line of the enterprise, and its reliance on wealthy underwriters to sustain its activities contributed to its gross financial insolvency. This, exacerbated by periods of broader economic troubles, was primarily responsible for its demise.

Artworks and Artists of The Wiener Werkstätte

Palais Stoclet

The Palais Stoclet represents the ultimate environment envisioned by the Wiener Werkstätte, as the cooperative received the commission during the brief period when Hoffmann had formally merged his architectural practice with the Werkstätte's activites. The program consisted of a palatial residence for the wealthy Belgian banking and railroad magnate Adolphe Stoclet, who in 1904 had just inherited a vast fortune from his late father, and gave the Werkstätte carte blanche. Hoffmann designed the house to maximize the two long facades: from the street it appears as an austere, stately urban mansion set amongst a verdant environment, with a formal covered pathway leading to the main entrance, while the rear, which opens onto a park, and onto multiple levels of terraces which facilitate several different views of the landscape.

The greater importance of the Palais Stoclet, however, lies in the interior, where Hoffmann and his associated artists used the most expensive materials available - gold, precious stones, rare woods, leather, and marble, among others. The key space within the house is the dining room, where Gustav Klimt - whose independent commissions separate from the Werkstätte included several portraits of the group's most enthusiastic patrons - designed a mural that wraps around three different walls. The mural shows a sprawling tree of life motif flanked on one side by a woman and the other by a couple in embrace; the characteristic panels of gold and other colors almost dissolves the figures into an abstraction that mimics the geometric patterns and panels of the rest of the room, including the furniture. The angularity, regularity, and severity of the geometries inside the house, combined with the luxurious tastes of the client, suggest the move in the years immediately preceding World War I to a craft-like, nearly Cubist ostentation that forecasted the emergence of Art Deco in the years following the conflict.

Brussels, Belgium

Wiener Werkstätte letterhead

The letterhead of the Wiener Werkstätte must have appeared startlingly modern for its time. In contrast to most organizations, whose letterheads frequently used intricate pictorial graphics of their factories and ornamental script-like or serif typefaces, the bold geometry, clean lines, and simplified lettering of the Werkstätte speak to a precision and straightforward approach to their work. The individual sections of the design are ruled by an overarching, repetitive set of boxes and borders, which use the exact same line weights as the arms of the sans-serif lettering. At the top left, one notices the interlocking "WW" logo of the Werkstätte, which almost completely blends in as if to demonstrate that its form is the "generator" from which the rest of the design proceeds.

The design thus uses a regimented order that mimics the uses of the forme and chase in manual printing-press typesetting. This is highly appropriate, as it arguably references the hybrid-like manner in which the Werkstätte functioned as a massive, craft-based workshop that nonetheless could not completely escape the use of mechanized production (as demonstrated by its furniture). Even nature itself, as suggested by the flower-like bloom on the right side of the letterhead, is abstracted - a further revelation of the hand of the artist - but also uses the same regimented boxes that reference the role of machine production.

In the broadest sense, the letterhead also indicates the impressive range of media in which the enterprise worked (especially in contrast to the massive tectonic scale indicated by the Palais Stoclet). More specifically, on the other hand, it demonstrates the seamlessness of the Werkstätte's graphic design, on multiple levels. This design, for example, resembles closely the layout of the address sides of the group's postcards.

Sitzmaschine chair

The Sitzmaschine ("sitting machine") chair, originally designed by Hoffmann for the Purkersdorf Sanatorium, a sort of combination hospital/spa resort, is the best-known piece of furniture produced by the Wiener Werkstätte. Its significance lies in the way it honestly discloses both function and construction without sacrificing aesthetic appeal. The legs and arms unite in dramatic curves that almost seem to suggest the forms of wheels of a machine itself in motion. Though the chair is pierced by gridded and slit-like openings, none of the lines or edges end in sharp corners, instead being rounded, which further underscores the notion of a well-oiled, harmonious machine. The exhibition of function, meanwhile, is evident in the set of balls on the back of the arms, which support a transverse bar behind the back and can be adjusted for different gradations of reclining for preferred comfort.

The chair's association with the machine is further extended with the choice of materials, as it uses bentwood for the curved pieces, a significant instance where the Wiener Werkstätte bowed to the dictates of mass production. It represents as well a specific instance in which Austria could claim technological innovation, as the process for making bentwood were perfected in the 1830s and '40s by Michael Thonet, a German manufacturer who moved his operations to Vienna in 1842. The Werkstätte outsourced the manufacturing duties for this chair to Jacob and Josef Kohn's firm, which, along with Thonet, was one of the primary companies used by the Werkstätte for furniture production. Nonetheless, for all its associations with utility, the chair is notorious for being anything but comfortable for its sitters. It thus reflects the nature of Hoffmann's design practice, wherein function was usually sacrificed to aesthetics when it became impossible to accommodate both.

Painted beechwood - Collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia

Rundes Modell flatware set

Hoffmann's designs for dining utensils also constitute some of the most recognizable items that the Wiener Werkstätte produced, able to be located in many museum collections in Europe and North America. This design exudes a rare sense of pure functionalism for the first decade of the new century, but one which is appropriate for the initial client of this design, the industrialist Adolphe Stoclet, whose business interests had to reflect a certain efficiency in order to be profitable.

Reintroduced by Alessi in 2015, this flatware line shows the simplification of the forms to their most essential characteristics: only handles and utensils, stripping away any extraneous ornament. The cylindrical shapes of the base of the handles of the forks and spoons taper to a thin flat plane as they reach the tongs or bowls, thus indicating the seamlessness between the hand of the user and the purpose the flatware serves. The only suggestion of decoration is the square incised at the base of the handle like a stamp that surrounds two W forms, indicating the items' manufacturer with an absolute minimum of required work. The clarity of form and identification thus disclose the fineness of the craftsmanship to which Werkstätte artists aspired. Ironically, the sense of efficiency that the utensils exude did not match the nature of the Werkstätte's design process, where organizational inefficiency and complete artistic freedom often contributed to wasteful expenses for materials and labor.

Silver - Collection of the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence, Rhode Island, USA

Wiener Cafe: Der Litterat (Viennese Cafe: The Man of Letters)

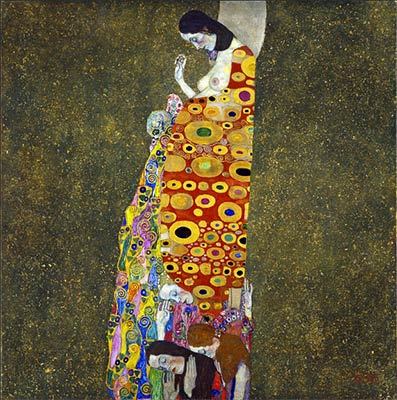

This design by the Czech artist Moriz Jung is one of the Werkstätte's most famous postcards, whose subject matter, like many of its sisters, is probably most significant due to the way it situates the Workshops firmly within the realm of Viennese municipal culture - in this case, the famous Vienna coffee house. In fact, due to the geographic specificity of their subjects, the Werkstätte's postcards perform this task of rooting the group in the city more effectively than any other type of item it produced.

The archetypal Viennese coffee house, whose form and function were well-established in the early-20th century, serves even today as one of the loci of the city's intellectual activity, acting as a kind of great reading room serving its eponymous drink to those who tend to linger for hours while working, discussing, or digesting a great number of newspapers. The postcard's imagery shows a caricatured example of one of the numerous writers - many of whom in real life were considered some of the most prominent Austrian intellectuals - who often inhabited the coffee house for long hours. He is slumped, presumably in a stretch of rumination - as suggested by his gaze to the space beyond the viewer - before putting the pen on his table to the paper nearby. His clothes, like his face, are rumpled in a way that suggests his intent concentration only on the work before him, and he sits on one of the high-backed upholstered seats covered in bright floral patterns, perhaps like those produced by the Werkstätte itself.

Chromolithographed postcard

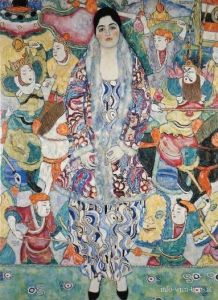

Afternoon dress

Textiles and clothing form important parts of the surviving Werkstätte items available today, as several museums conserve considerable collections of the enterprise's fabric swatches and samples. While this is fortunate for research purposes, the wide variety of patterns make it difficult to choose a single object as representative of the Werkstätte's work as a whole. This dress, however, holds special prominence as a favorite of Friederike Maria Beer, one of the Werkstätte's most devoted patrons, who insisted that Gustav Klimt depict her wearing it in a 1916 portrait (a commission otherwise unrelated to the Werkstätte). Indeed, the portrait reifies the design to a level of immortality: everyone who owned one could thus imagine herself as dressing in a Klimt painting.

The dress, created by two of the Workshops' chief fashion designers, represents some of the Werkstätte's innovative ideas about female fashion. Its irregular pattern of curved lines and regions, which requires one to look closely in order to detect the repetition within, also functions to obfuscate the actual shapely curves of the person wearing it. The free-flowing nature of the pattern also reflects its very nature as an "afternoon dress," not intended for formal events, but for casual and carefree occasions. The colors of cream, blue, and tones of gray, together with the pattern, also abstractly recall the idea of running water tracing over and dripping from the contours of the human body, or the rippling of bodily forms like hair due to wind, thus deftly adding a layer of sensuality to a garment that otherwise conceals nearly the entire figure.

Silk - Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Cup

Glassware formed an essential part of the Werkstätte's production from the outset, and remained as such until the Workshops' closure in 1932. Like textiles and clothing, Wiener Werkstätte glassware is so varied as to preclude easy choices to represent all its pieces. This cup, however, is significant on several levels. First, it illustrates the collaborative nature of much of the Werkstätte's designs, as Josef Hoffmann was responsible for the shape of the vessel and Mathilde Flogl, one of the Workshops' important women artists, completed the decorative painting.

Also importantly, one can also quite clearly see the enormous influence of Dagobert Peche on other designers some three years after he joined the Werkstätte: here Hoffmann has abandoned the strict geometries characteristic of his architecture and design for the applied arts between 1900 and 1915 in favor of a more decorative set of concave and convex profiles, particularly in the stem and base, but also in the flared lip. These recall the forms of Baroque and Rococo designs, and are highlighted by the way that Flogl has chosen to paint the lower half of the vessel in the alternating white and blue stripes.

Flogl's decoration of the actual cup, meanwhile, is highly fanciful, mixing forms of birds, humans, potted plants, and deer with abstracted curves and twisted lines in a non-narrative manner; it likewise recalls the work of Peche, such as the gilt jewel box of his from two years later. The simplified forms, floating almost randomly on the surface of the vessel, seem to ask the user to choose or fashion a connection between them purely from the imagination, and perhaps serving a potential utilitarian purpose as a conversation starter over a drink. In some ways, therefore, they anticipate the developments of both Surrealism and German Expressionism during the 1920s.

Painted blown glass - Collection of the Österreichisches Museum für angewändtes Kunst/Gegenwartskunst, (Austrian Museum for Applied/Contemporary Arts), Vienna

Jewel Box

This silver jewel box is exemplary of Dagobert Peche's creative work for the Werkstätte, which dazzled Josef Hoffmann and his colleagues from the moment that they met Peche in 1911. The box uses the motifs of a deer frolicking amongst grapevines, with the ground it stands on serving as the lid of the container. This is, in turn, perched on top of four pine cones that both serve as the legs and contain individual storage containers themselves - thus exhibiting the piece's ultimate utility. The curves of the deer's body and the vines and the deep ridges of the surfaces of the container recall the exuberance and ornamental qualities of Baroque and Rococo design, exhibiting a sharp contrast to the severe abstracted geometries of Hoffmann's early work.

The jewel box's artistic qualities exhibit several ironic twists: while the piece ostensibly functions to protect and guard valuable stones or other objects, its own precious materials and craftsmanship also rival whatever might be stored inside. On one level it only magnifies the precious nature of what it contains, both in the way the gold conceals the silver and the way it encapsulates other desirable objects. On the other hand, the valuable exterior means that it arguably ceases to perform its intended function and becomes its own precious object requiring proper safekeeping. The ultimate significance of the case, thus, might be that it subverts the honesty of construction and function common to modern architecture and the applied arts in favor of an increase in its fetishistic qualities. This aspect, along with the box's highly exuberant forms, presciently forecasts the emergence of Art Deco and the materialistic values that characterized the culture of the Jazz Age over the coming decade.

Gilded silver - Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Beginnings of The Wiener Werkstätte

The Wiener Werkstätte grew out of the Vienna Secession, the movement with which many of its chief designers were affiliated, and was part of the larger emergence of the importance of the decorative arts in Vienna at the turn of the century. Founded on 3 April 1897, the Secession consisted of a group of artists who resigned from the Association of Austrian Artists, which ran the Kunstlerhaus (Artists' House), the only venue in Vienna for the exposition of contemporary art. The Association of Austrian Artists favored the work of conservative, academically-minded painters and sculptors to the detriment of progressive-minded ones, as well as decorative artists.

The leaders of the Secession included Joseph Maria Olbrich, Josef Hoffmann, Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Max Kurzweil, Wilhelm Bernatzik, and several other artists. Klimt served as its first president. In January 1898, the group began publishing its own journal, Ver Sacrum (Sacred Spring), and Olbrich designed its famous exhibition building, completed that year. The Secession also gained significant credence in 1898 when Otto Wagner, the most respected name amongst Austrian architects and a professor at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, joined the group, a move that shocked the national academic establishment.

The Secession was the group most associated with the development of Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) in Austria. It favored the international exchange of artistic ideas, and welcomed artists such as the Scottish architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh to exhibit in Vienna. Mackintosh's highly geometric and rectilinear forms exerted a great influence on Austrian designers, as did the work of designers from the British Arts & Crafts Movement, whose work had generated much enthusiasm in Germany and were known for their emphasis on utilitarian design.

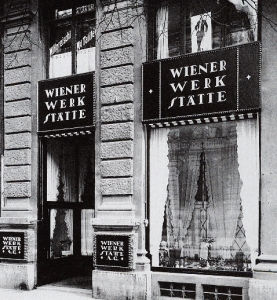

Inspired by these examples, in 1903 two Secession members, the architect Josef Hoffmann and designer Koloman Moser, formed an even-more-specific organization, the Wiener Werkstätte, dedicated to the artistic production of utilitarian items in a wide range of media, including metalwork, leatherwork, bookbinding, woodworking, ceramics, postcards and graphic art, and jewelry. The Werkstätte set up shop in three relatively small rooms but soon expanded in October 1903 to a full three-story building, with facilities that were lauded by the contemporary press. The Werkstätte was backed financially by Fritz Waerndorfer, a wealthy textile industrialist who had shown great enthusiasm for the Secession.

Building a Brand

The Wiener Werkstätte had an auspicious beginning. In 1904 its artists exhibited for the first time at Berlin's Hohenzollern Kunstgewerbehaus (Decorative Arts House), for which the art journal Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration published the first article on the enterprise, and soon developed a very close relationship covering the Wiener Werkstätte's activities. The Werkstätte also received its first official commission that year, for the production of a lavish publication commemorating the centennial of the Austrian Imperial and Royal Court and State Printing Press.

Initially, Hoffmann merged his architectural practice with the workshop's activities, which he ended after a lawsuit in 1905. He received commissions for the Purkersdorf Sanatorium in 1903 and Moser contributed stained-glass windows for the Steinhof Church, designed by Otto Wagner, Hoffmann's mentor at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts in the 1890s. In 1905, having only completed a handful of houses in Vienna, Hoffmann received the commission for the Werkstätte's most important undertaking: the Palais Stoclet for the banker and railroad magnate Adolphe Stoclet in Brussels, whose design and construction would occupy the group for the next five years.

The Werkstätte relied heavily on its participation in expositions all over Europe to help build a network of clients. Along with the German-speaking countries, Great Britain provided the Werkstätte early opportunities for exposure, and during the First World War the organization sustained its activities despite undoubtedly the shortages of materials, exhibiting in neutral countries like Switzerland and Sweden. After the war, Austria - unlike Germany - was not blacklisted from international fairs, and the Werkstätte was represented well at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris (which gave us, forty years later, the term Art Deco), in the extremely modern Austrian pavilion designed by Hoffmann.

Stylistically, the Wiener Werkstätte did not adhere to any stated set of guidelines. The principles of its founders were very similar to other progressive movements of the period. The focus on the design of utilitarian objects included the use of materials in ways consistent with their natural properties, emphasized the goal of raising the status of the decorative or applied arts in relation to the traditional dominance of painting and sculpture, and aimed to be in tune with current thinking and trends. Thus the real aesthetic qualities of the Werkstätte were often left to the individual designers, with the result that scholars and collectors can easily assign many of the workshop's examples to their creators at first glance.

Expansion, Sales, and Distribution

The Werkstätte soon expanded its activities into a highly complex network of artists, craftsmen, sales outlets, and production sites. In 1910 it established a fashion department and the next year opened showrooms exclusively for fashion and textiles on the Kärtnerstrasse in a fashionable district of Vienna. Eventually it would add retail locations in Marienbad and Zurich in 1916, New York in 1921, Velden in 1922, and Berlin (for just a few months) in 1929. Increasingly after 1910 it became far less known for its work in creating entire built environments than for the individual pieces of decorative or applied art such as its glasswork, ceramics, fashion, and graphic work.

Meanwhile, the Werkstätte, which officially reported that it employed some 100 workers in 1905, including 37 master craftsmen, established various types of affiliations with other firms and artists. Some of these produced Werkstätte designs; others sold the Werkstätte's products in their own stores; some individual artists and firms produced items that the Werkstätte itself sold in its storerooms, sometimes on consignment or where the artists were paid by the piece with the Werkstätte acting as a middleman. Some artists, such as Gustav Klimt, produced occasional work in concert with the Werkstätte without formally joining it.

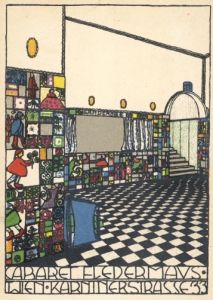

Starting in 1907 the Werkstätte functioned as the distributor for the Wiener Keramik, a ceramics enterprise founded by Berthold Loffler and Michael Powolny the previous year. The Wiener Keramik would supply tilework for some of the Werkstätte's most significant commissions, such as the famous interior decor of the Cabaret Fledermaus in Vienna from that year. Most importantly, perhaps, from the start the Wiener Werkstätte worked with the Backhausen textile company in Vienna, who produced many of the firm's fabric designs, including those for some of the Werkstätte's most important commissions, such as the Palais Stoclet and the Villa Primavesi in Vienna.

Relationship with Mass Production and Industry

The factory-like structure of the Wiener Werkstätte, with a large cadre of official and unofficial employees, might suggest that it would wholeheartedly embrace the new means of mass production and assembly-line techniques that were quickly transforming the face of modern industry worldwide. Yet this was not the case. The Austro-Hungarian Empire (and, after World War I, merely Austria itself) was not a heavily industrialized country or even one whose population cultivated a rich and broad artistic sensibility. Small collections of industries remained scattered around the Empire and its unwieldy amalgam of different nationalities, most of whom deeply resented the favoritism shown to Austrians and Hungarians. All of these factors meant that Vienna almost exclusively had the population and industrial capacities to support the cooperation of art and industry, and handcraft was the norm for most utilitarian goods.

The Wiener Werkstätte even officially acknowledged that it favored the specialized output of artists and craftsmen over the streamlined output of mass production, which it feared would lower the quality of goods it produced. This stood in stark contrast to the rapid industrialization in (for example) Germany, where designers and industrialists united formally in an organization called the German Werkbund to align both of these fields (though not without famous disagreements, such as the confrontation between the two factions at the Cologne Exhibition of 1914). Although before World War I Hoffmann had helped to organize a similar organization, the Austrian Werkbund, its ability to coordinate between designers and producers never approached the organizational successes of its German counterpart.

In contrast to many other design movements, a significant number of the artists of the Wiener Werkstätte were women. Maria Likarz, Jutta Sika, Mela Kohler, Valerie ("Vally") Wieselthier, and Mathilde Flogl, for example, were responsible for many of the Werkstätte's designs in a wide variety of media. These included textiles and fashion, principally, but also extended to graphics and ceramics. Unfortunately, the traditional male-chauvinist climate of the era meant that critics blamed the ultimate decline of the Werkstätte's fortunes in the 1920s on the influence of female designers, despite the absence of real evidence to that effect.

Clientele

One of the consequences of the decision of the Wiener Werkstätte to eschew the methods of mass production was the narrowness of its customer base. Unlike the aspirations of the practitioners of the Arts & Crafts Movement in Britain or the United States or Art Nouveau in European countries, the Werkstätte's aim was never to appeal to individuals of all backgrounds and to make art accessible to the working classes. Instead, it relied on a more refined audience, mostly upper- and middle-class clients in major metropolitan areas, including large numbers of Jewish supporters, or artists who were already included within its circle.

The Wiener Werkstätte: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Architecture

The Wiener Werkstätte was heavily influenced by the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk that permeated the thought of Art Nouveau and the Arts & Crafts Movement at the same time. After the 1902 Turin Exposition of Modern Decorative Arts, however, Art Nouveau entered its definitive decline in the German-speaking countries, thus prolonging the search for a unifying set of visual forms to represent the modern world of the new century. The buildings and interiors of the Wiener Werkstätte, therefore, represent the most complete vision of a modern environment that Hoffmann and his associated artists could produce, requiring the coordinated effort of the multitude of Werkstätte craftsmen and designers. Hoffmann's status as the group's only real architect was unusual for modern collective artistic movements, and as the only leader of the Werkstätte who remained affiliated with it for the entirety of its existence, his hand is evident in virtually every area of the Werkstätte's production.

This vision is made permanently evident in the major houses that the Werkstätte artists designed, for which they were given virtually carte blanche, in particular Adolf Stoclet's residence in Brussels. The absence of official public commissions in the city following the completion of the Ringstrasse's governmental and institutional buildings in the 1880s meant that the Werkstätte's built structures remained relatively few and far between. Other examples, however, can be seen in the interiors of various commercial establishments, such as cafes and salons, that the Werkstätte worked on - and sometimes distributed on postcards, such as the famed issues of the colorful tilework of Vienna's Cabaret Fledermaus - as well as the photographs of numerous temporary designs for interiors that the Werkstätte produced for exhibitions.

Furniture

The furniture produced by the Werkstätte remains some of the group's most recognizable work. It was a natural genre for the group to pursue as a foundational pillar of the decorative arts and for architecture, as the interiors for which the Werkstätte became especially famous both at exhibitions and for commercial clients demanded furniture as a prime component of the design.

Much like the Arts & Crafts Movement, there is an emphasis on the honesty of construction and the materials used in Wiener Werkstätte furniture. Hoffmann and Moser were initially the two artists responsible for furniture design, and the two can be distinguished from each other often by the materials used, reflective very much of their backgrounds. While Moser - the painter by training - was fond of using inlay to create gradations of color in otherwise blocky, massive pieces that have been said to look better as two-dimensional designs, Hoffmann - the architect - was more inclined to a lighter structure that included solely material necessary for the piece to function. Hoffman's pieces, especially the chairs, frequently make use of his favorite grid of squares puncturing the wood panels, thus revealing their true thickness and mass.

The Werkstätte tended not to produce its own furniture designs, though it was equipped with facilities for shaping wood; the bentwood pieces, such as Hoffmann's famous Sitzmaschine chair, were entrusted to Gebruder Thonet or J. & J. Kohn. The manufacture of bentwood itself was not an especially new process, having been perfected in the mid-19th century, but it was one of the most modern industries in Vienna and was invented by the cabinetmaker Michael Thonet, who moved to the city from Germany in 1842 and relocated his business there. Thus, it was appropriate that, in a relatively backward technological state such as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the instances in which the Werkstätte used modern manufacturing methods were for products pioneered by Austrians.

Both architecture and furniture, the two largest scales of design produced by the Wiener Werkstätte, were most prominent in the group's production before World War I. As the client base for the Werkstätte became increasingly limited during and after the war (when the Austro-Hungarian Empire was dissolved), the commissions in these fields correspondingly dried up.

Glass

Most of the Werkstätte's glasswork was produced as functional drinking vessels, regardless of whether they were destined for actual use. The other major area in which the Werkstätte relied on other firms for manufacturing was glass, produced historically in the regions of Bohemia and Moravia that are now part of the Czech Republic. Instead, the Werkstätte licensed firms in these areas to produce designs, initially by Hoffmann and Moser, and upon receipt of the blown and shaped pieces back in Vienna, another artist - after 1915 often a woman - would paint them by hand.

Fashion and Textiles

The Werkstätte's fashion and textile departments were not part of the initial program of the group, but by 1911 they had both been separately established and given their own showrooms. They soon became some of the most important parts of the Werkstätte's designs, and a mainstay of the production in the last fifteen years of the group's existence, especially when other areas of the Werkstätte's design program were declining. The Werkstätte built a new factory for fashion and textile production in 1914, and expanded the showrooms in Vienna in 1919. In 1924, it officially boasted 150 employees in the fashion division, which was technically spun off as an independent company (though it was reattached three years later). Initially headed by Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill and then Dagobert Peche, by the early 1920s most of its artists and craftspeople were women, including some of the more famous designers of the group such as Mela Kohler and Maria Likarz.

The fashion and textile departments also cultivated a close relationship with the Werkstätte's graphic design section, as fashion photography in Vienna was still in its infancy throughout the 1910s. As such, the Werkstätte's postcards became one of the prime vehicles for advertising clothing and textile patterns, some of which might be featured on cards with other purposes, such as holiday greetings.

Postcards

To a large extent, the exclusivity of the Wiener Werkstätte's items is reflected even in their pieces that are available on the market today, despite the wide variety of media they produced. The fame of the artistic postcards produced by the Wiener Werkstätte - which depict an extremely wide variety of subjects, from the group's architecture and fashion designs to characters from children's narratives - help to set the Workshops apart from many other design movements. The postcards functioned in a way to advertise the activities of the Workshops both in graphic design and many of their other media, particularly the designs for women's fashions and the interiors of cafes and shops Hoffman and his collaborators completed.

The postcards are serially numbered and can be dated given the number assigned to them; in many cases, they also contain the prominent monogram of the designers of the items depicted, acting like a signature, as if to give the artist's official approval of the work's final form. They thus constitute one of the fairly rare instances wherein ephemera is truly raised to the status of high art. The stature of Wiener Werkstätte postcards as art objects is only reinforced by the particular individuals who are known to collect them - including the cosmetics magnate Leonard Lauder, whose promised gifts of his cache of Werkstätte postcards have caught the eye of several prominent museums and have been the subject of several recent exhibitions.

While nearly ephemeral Wiener Werkstätte items such as postcards can be collected, they nonetheless command a premium when offered for sale, especially because of their associations with some of the best Austrian designers of the era. Even when sold during the early-20th century, the cards were often considered collector's items and not sent through the mail, and to attest to their popularity, the Werkstätte itself would display them in its shop windows. It is now probably much more difficult to locate a Wiener Werkstätte postcard that has been postmarked than an unused example.

Metalwork and Ceramics

As the postcards demonstrate, the notion of the Gesamtkunstwerk as extending to covering every aspect of the human environment held true for the Wiener Werkstätte even down to the smallest items. Metalwork initially was reserved for highly functional items, such as baskets for desktop organization and other useful containers. Hoffmann's penchant in his early pieces for the repeated grid of punched squares through a piece of sheet metal, forming a waffle-pattern structure called Gitterwerk, became one of the Werkstätte's most recognizable designs. The repetitive, pure forms, uncluttered by extraneous decoration, look modern and highly functional to us even today. Similar features could be described in the Werkstätte's ceramics production before World War I.

In 1915, the addition of Dagobert Peche to the Werkstätte staff changed the course of the group's designs, instilling a far more enlivened, theatrical, and baroque sensibility to them that in some ways look modern, with their fragmented forms that appear as if they were picked up from the scrap pile and strange, non-narrative combinations of figures, and in other ways look retrograde due to their use of familiar imagery, like animals and plants. Some clearly reference Art Nouveau and other contemporaneous styles and movements, such as Peche's chandeliers that appear like tree branches and leaves. The collaborative nature of the Werkstätte's environment meant that Peche's designs became infectious; Hoffmann virtually abandoned the extreme geometries of his early work for an abundance of sensuous curves, knobs, and protruding handles.

Typography and Graphic Design

Peche's arrival also prompted a revolution in the Werkstätte's graphic work. The Werkstätte's official logo, created by Moser around 1903 but not registered officially until 1914, consisted of an interlocking sans-serif "WW" that uses thick weights for the characters' arms, framed by a square with a weight of equal thickness; it formed the basis for most of the group's early typography. The affinity for such rectilinear qualities mirrors the forms seen in the Werkstätte's contemporaneous work in most other fields, as the artists' monograms found on Werkstätte designs and the initials of clients stamped on personalized pieces before the war all usually contained stylized letters set within a square border. The emphasis on the two-dimensional surface, meanwhile, constitutes an homage to honest graphic design in its pure form and forecasts the sans-serif lines used by many Bauhaus designers such as Herbert Bayer.

While this logo lasted for the duration of the Werkstätte's existence, the group's typography underwent profound changes; Peche's influence introduced serif characters of varying weights that created the illusion of three-dimensionality, strongly resembling the typefaces simultaneously popular in Art Deco graphics of the 1920s.

Later Developments - After The Wiener Werkstätte

The prime issue for the Wiener Werkstätte was, unsurprisingly, money, which was problematic from the start. Koloman Moser left the enterprise as early as 1907, partly due to the fact that he did not want his wealthy wife (whose accounts were kept separate from his own) to become entangled with the group's finances, and was insulted when Warendorfer and Hoffmann went over his head to directly ask her for a loan.

The Werkstätte never was able to become financially solvent on its own, and relied constantly on Warendorfer's capital to support a huge number of craftsmen and their activities. Its relationship with its benefactors could probably be best described - as Jane Kallir has indicated - as constantly looking for a "milk cow" that would continue to pour money into it without expecting a return on the investment. This was essentially Warendorfer's understanding of his role until he essentially went bankrupt in 1913 and - having been long considered the black sheep of the family - his relatives shipped him off to the United States after settling the organization's debt.

The problems were exacerbated by the Werkstätte's limited client base from the start, as it never intended to truly develop a mass appeal or accessibility for its items. These limitations sometimes fed back on themselves, as the Werkstätte counted many of its own and related artists among its clients, who, if unpaid, would also be unable to compensate the Workshops for the work and materials expended on its own projects.

In 1914 the Wiener Werkstätte was liquidated and reorganized as a private corporation, and found another backer, the banker Otto Primavesi, whose business contacts and acumen for a time in the late 1910s seemed to produce a profit amongst some of the Werkstätte's various branches, especially with Primavesi's ability to get the Werkstätte to exhibit at international trade shows. Otto Primavesi's cousin Robert even commissioned an entire house from Hoffmann and the associated Wiener Werkstätte artists in Vienna in 1913. In 1915, Dagobert Peche joined the Werkstätte and reinvigorated much of the small-scale production of clothing, textiles, ceramics, metalwork, and crafts with an infectious, baroque personal style that soon spread to many other Werkstätte artists, including Hoffmann, who soon abandoned the severe geometries that had characterized his earliest designs for the group.

But this second wind was short-lived. As World War I dragged on, resources and money amongst the Werkstätte's clients became increasingly tight, and these only deepened with the defeat of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and its breakup in the war's aftermath. Material shortages plagued the Werkstätte, making it difficult to produce items with genuine silk, silver, gold, and other metals, stones, and fabrics as originally envisioned. The quality of craftsmanship suffered as a result, with products that began to appear more like cheap knockoffs or knickknacks than fine art, damaging the Werkstätte's brand.

In the early 1920s, Philipp Häusler was brought in to reorganize the Workshops, and discovered that Hoffmann's system of allowing artists complete creative freedom had created an unsustainable environment of waste and ineptitude. Often craftsmen of questionable ability had been hired, including some of Primavesi's destitute relatives, with the result that their work squandered materials and time when it had to be scrapped altogether. Häusler's reorganization efforts may have been too little too late, as he was fired in 1925. In 1926 Primavesi's bank failed, and soon the Werkstätte went into receivership before its creditors granted it a reprieve, but the stock market crash of 1929 finally did it in. By 1931 it was clear that the Werkstätte would not survive, and its remaining inventory was sold off in September 1932.

Legacy

Despite its persistent financial troubles, the Wiener Werkstätte today represents the height of Austrian decorative art design during the first half of the 20th century, and examples of its work exist in dozens of museums and private collections, mainly in Europe and North America. Perhaps due to its remarkable emphasis on artistic freedom and its commitment to the spirit of the times, its designers' work did not seem to go out of style while it existed.

At its outset, the works of the Werkstätte artists anticipated the turn away from Art Nouveau that soon became apparent across Europe in the first decade of the 20th century towards a more severely geometric aesthetic. On the one hand, this harmonized with the revival of interest in classicism, which would eventually morph into Art Deco in the 1920s, a style with which many late Wiener Werkstätte designs exhibited a number of similarities. On the other hand, the simplicity of forms also reflected a minimalist aesthetic and emphasis on functional design that reflected the values of the Bauhaus in Germany, especially the emphasis on craft that Walter Gropius and his faculty promulgated during the school's early years.

The rights to the original designs of the Wiener Werkstätte are owned by various companies and many of them are still in production today. Backhausen, for example, owns a large number of the textile schemes, and WOKA owns a significant portion of the lighting designs. Backhausen even maintains a Museum of the Wiener Werkstätte in the basement of its headquarters in Vienna.