Summary of Max Liebermann

Liebermann is widely celebrated as both a forerunner of German Impressionism and as the founder of the influential avant-gardist Berlin Secession. Drawing on the techniques of French Impressionism and the Dutch Hague School, his naturalistic painting departed from the traditional methods and genres of academic German art. Galvanized by the paintings Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas, he began to experiment more and more with light and color on canvas. But while his formal approach became secondary to subject matter (as it was for the French masters), Liebermann always remained true to the narrative traditions of German art. Indeed, his art drew upon a wide range of subjects, from the travails of hard manual labor, to the leisure pastimes of bourgeois German society. In the autumn of his career, Liebermann led the Berlin Academy, and was elected its president until the Nazis came to power and forced him to resign his position shortly before his death.

Accomplishments

- One of Liebermann's key influences and mentors was Jean-Francois Millet, co-founder of the French Barbizon School. His adopted thus the painterly codes of naturalism which permeate his early paintings of rural peasant life and of the hardships of manual "workhouse" labor. Yet Liebermann was able to transform his material into something more personal without resorting to the glorification of his subjects (as was the charge often levelled at Millet).

- Liebermann left behind his early commitment to Realism in favor of a more spontaneous, impressionistic approach. He addressed himself to the challenge of representing the themes of the urban leisure and recreational activities of Berlin's bourgeois classes with a new vivacity. In his new commitment to representing what was familiar in a new way, he turned towards a more varied color palette which he applied using less refined brush strokes.

- A thematic feature of Liebermann's later period was his liking for open spaces. Liebermann tended to resist painting pure landscapes, however, preferring to punctuate his scenery with spontaneous observational, or "anecdotal", details and movement. This narrative characteristic in Liebermann's work has sometimes seen him associated with the German Realist Adolph Menzel who was known for his keen senses of observation and his skill at capturing the essence of everyday German life.

- In addition to his narrative paintings, Liebermann is less well known as a painter of portraits, this despite the fact that he accepted over 200 commissioned portraits of distinguished figures from the fields of commerce, science and politics during his lifetime. His most famous sitters were the world-renowned physicist Albert Einstein, and the second president of the Weimar Republic, Paul Von Hindenburg.

Important Art by Max Liebermann

Women Plucking Geese

This work shows a darkened room in which several mature women pluck geese. There are baskets of feathers at their sides. A sense of stoicism permeates the room, which appears quite impoverished and dirty, with hay and feathers lying on the floor. A man is shown bringing more geese to the women and his presence adds the only hint of social interaction to the narrative on working-class rural life.

This work was Liebermann's "breakthrough" painting, though it was widely criticized and earned him the nickname "apostle of ugliness." The painting is indicative of Liebermann's preoccupation with Dutch culture having spent many summers in Holland and it considers the birth of German modernism, which took much of its influence from 16th and 17th century Dutch and Flemish painting. Liebermann's own modernist works were also strongly influenced by Dutch painters Anton Mauve and Jozef Israëls. Liebermann was fascinated with the mundanity and unassuming nature of rural life in Holland, and spent many years trying to capture its essence in his paintings. However, this work does not capture the serenity that Liebermann must have felt in the Dutch countryside. In fact, the work has a certain lackluster quality; the women working appear overworked and tired. Perhaps Liebermann sought to elucidate the cyclical and unforgiving nature of manual labor, which was undertaken out of necessity. His fascination with such a lifestyle displayed his early affection for a socially conscious aesthetic.

Oil on canvas - National Gallery, Berlin

Self-Portrait in Kitchen with Still-Life

This work portrays Liebermann himself (in a chef's cap) smiling over a group of cabbage, cauliflower, mushrooms, carrots, leeks, potatoes and a dead chicken. On the left of the frame sits a large copper pot while the leafy greens are in a large wicker basket covered with a cloth. This work is significantly darker than some of Liebermann's other early paintings given that the background is almost completely black.

There are several symbolic connotations to this work. The vegetables may represent his time spent in rural Holland, and their unorganized arrangement suggest the naïve virtuosity of his early career. The obscured background could also allude to the feeling of uncertainty which he felt at this early point in his career. The work also poses an interesting juxtaposition between his "high art" treatment of "low art" subject matter (namely a kitchen still-life) and his still lifes follow in the proud tradition of Dutch still life painting which hid a symbolic depth behind lavish "banquet scenes" and the more humble "breakfast pieces" to which this image alludes. But the painting may have also represented Liebermann's self-image as a craftsman and a creative artist, in the way that chefs were thought of during the time. The cruder subject of the work may have even sought to elucidate the idea that the craft of painting was of more importance than the subject matter. Additionally, the kitchen setting could be a tribute to his mother, who was known to have loved to cook, with the chef cap acting as a metaphor for his bond with her.

Oil on canvas - Stadtisches Museum, Gelsenkirchen

The Flax Spinners

This work, another of his ruminations on rural labor, depicts a group of orphans working in an unkempt weaving mill. Some are pictured holding out the string whilst others sit in a line, each on their own spindle, weaving flax. The room is bleak, as is the mood of the orphans, who all wear dark, drab clothing and look down towards to floor. Nevertheless, some hope exists in the sunlight that is allowed to enter the composition through the windows.

Liebermann demonstrates the permeation of slow-moving, casual rural life with the ordered, timely, cold and industrial urban world. Every figure within the work is so lost in thought they appear almost robotic, as if cogs in a large machine in fact. They also wear the same clothing emphasizing thus the uniformity and order of factory-like manual labor. The industrialism of the work is exemplified indeed by Liebermann's use of strict horizontals and parallels and the bleak blue and gray tones that are omnipresent in the work. The darkness inside the room, with the only light coming in through the windows shows how warmth and slower pace of rural life has been stripped away, perhaps alluding to the incoming industrial wave.

Oil on canvas - National Gallery, Berlin

The Parrot Man

Liebermann's Parrot Man depicts a working man - a zoo warden probably - in a sunny and warm Berlin Zoo. He holds three parrots one held up in his right hand and two below with his left hand. Reflecting his more adventurous use of color, the parrot in his right hand is blue, while the others are red. Another smaller (red) parrot sits on his cap. The Parrot Man himself wears a worker's "uniform" of black cap, blue jacket and brown pants.

The zenith of German Impressionism came in the decade after the establishment of the founding of the Berlin Secession (in 1898). Amongst the most important works were Liebermann's zoo paintings - The Parrot Man and The Parrot Walk (at Amsterdam Zoo, both from 1902) - and a number of beach scenes. His choice of subject matter reflects his immersion into leisure and culture in Berlin (and Amsterdam). He was by now a prominent painter and political activist who brought Berlin to the forefront of European modernism. His more varied use of color and less defined brush strokes indicate this; challenging the more realistic, more monochromatic images that characterized his earlier works. This new frivolity seemed to reflect his immersion into a more diverse and colorful culture in Berlin. The lack of strict linearity may also indicate the more leisurely approach towards his new subjects.

Oil on canvas - Museum Folkwang Essen

Terrace at the Restaurant Jacob in Nienstedten on the Elbe

This painting depicts a convivial outdoor scene at a bourgeois restaurant. The restaurant sits on the banks of the Elbe and within a colonnade of trees. The patrons, wearing colorful clothing, engage with one another and there is a sense of community amongst them. It appears to be summer, as the patrons' clothing is characterized by light colors and they do not wear jackets. The tables and chairs are painted white and the painting generally has a light color palette.

This piece demonstrates the turn of the century shift in Liebermann's in focus from rural, working class scenes in Holland, to leisurely days enjoyed by Berlin's bourgeois classes. There are several characteristics within the work that mark the stark contrast between the two periods. Firstly, all of the figures in this painting wear light, airy and varied clothing, whereas in Liebermann's earlier works the figures wear dark, uniform clothing. Also, the figures in this piece enjoy a relaxing lunch on the river, interacting with one another; any social interaction like this was a hint of luxury that is lacking in works such as Women Plucking Geese. Overall, this work has a lighter, warmer tone than the earlier works. We may note too that the scene is set outdoors, whereas the working paintings are set in a dark, claustrophobic indoor spaces.

Oil on canvas - Hamburger Kunsthalle

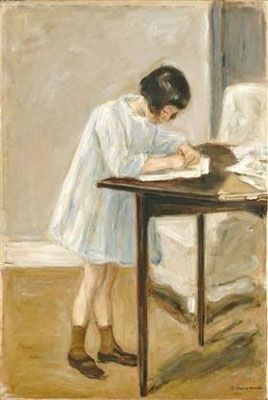

The Artist's Granddaughter at the Table

This piece portrays Liebermann's granddaughter Maria leaned over a wooden table. She appears to be either drawing or writing. She has short dark hair and wears a white dress with brown socks and shoes. She is in a well-lit, beige room with a darker floor. The painting exudes thus a mood of relaxation and nonchalance.

This work, painted late in Liebermann's career, is set in his villa at Wannsee. It is quite characteristic of this late period: almost all of Liebermann's paintings set within the villa and its gardens are painted in pastel shades. This contrasts Liebermann's bold coloration of other works set during the Berlin Secession or in Holland, suggesting that Liebermann, no longer subject to the criticism that plagued him throughout most of his career, felt a sense of quiet contentment and escape in Wannsee. Though he produced at least one self-portrait that showed him in a somber mood, Liebermann painted his daughter Käthe and granddaughter with great warmth and fondness. This shift in subject matter alludes also to his withdrawal from his leadership role within the German art establishment; a situation precipitated by the rise of the Nazis Party who demonized his art and subjected his activities to intense scrutiny. His portrait of his granddaughter Maria clearly marks the artist as a "recluse" who, having been an active member of society in his earlier years, now reclines as a quiet observer of the next generation.

Oil on canvas - Staatliches Museum, Schwerin

The Birch Alley in the Garden of Wannsee

In 1910, Liebermann started work on what would be his summer residence on the edge of Lake Wannsee, south-west of Berlin. The design of the villa and its gardens reflected the ornamental architecture, interior design and landscape principles as espoused by the Art Nouveau movement. Liebermann and his family would be residents of the villa between the months of April and October until his death in 1935. The gardens, which were designed together with his friend, the art historian Alfred Lichtwark, were intended to serve both as a place of rest and an "open air workshop" (that would ultimately inspire some 200 paintings). The architecture, interior design and landscaping worked in complete harmony but it was the warren of hedges, the gardens, and the birch grove that provided the artist with so many painterly motifs.

According to the philosophy of Art Nouveau, birch wood was symbolic of spring and the flowerings of youth. Lieberman's picturesque Birch Alley features close framing that plays on the geometric dynamic of the vertical trunks of the birch trees and the path of the trees that acts as a framing device for the view on the architectural splendour of the villa. Liebermann employs thick impressionistic touches of natural color, sometimes applied with a spatula, as a means of conveying the shape and flowing movement of the foliage.

After his death, Liebermann's family was forced to leave the villa by the Third Reich which took control of the property for the purposes of a Post Office. Following the war, the villa formed part of the Wannsee hospital and Liebermann's studio was converted into an operating theater. It was not until the end of the 1990s that the Max Liebermann Society secured a "historical building" status for the property and duly undertook the reconstruction of the garden and the house as a museum which opened to the public in 2006.

Oil on canvas - Gessellschaft Berlin

Biography of Max Liebermann

Childhood

The second child of four, Max Liebermann was born in 1847 in Berlin to Louis Liebermann, a wealthy Jewish manufacturer, banker and councilor, and Philippine Liebermann (née Haller). In 1860, The Liebermann family bought the "Dannenberg'sche Kattun-Fabrik", one of the leading

companies for the production of cotton in Europe. Both parents were prominent members in the German business world and their son enjoyed an affluent upbringing in a bourgeois home in Pariser Platz, near the Brandenburg Gate. He received an excellent education as well as the self-confidence of growing up in a financially secure family.

Liebermann was raised as an observing Jew, but was afforded a more secular education, one that complimented his parents' busy lives and prepared him for a future career in business. For instance, Saturday was not treated as a day of rest because schools and offices in Berlin were open for business on Saturday mornings. Through his school education, Liebermann developed self-control, discipline and an unrelenting work ethic that he would carry into his art practice.

Liebermann and his siblings attended a makeshift class in a Berlin Gymnasium where they were taught Latin and Greek (though they were not taught Hebrew). As an assimilated Jew, he described this element of his education as "Prussian," and drew on the 16th century Germanic state to articulate his feelings and ideas. From the age of nine, Liebermann began to exhibit an interest in the arts. Although his parents tried to discourage their son's "folly", painter Carl Stiffest took note of his artistic abilities and encouraged him to continue with painting into his teenage years.

Early Training and Work

Prompted by his parents, Liebermann enrolled at the University of Berlin to study Law and Philosophy. However, he remained passionate about art and between 1866 and 1868 secretly resumed his education with Steffeck. While Steffeck was pleased with his student's progress, Liebermann felt that he was not getting a complete arts education and enrolled in the Weimar Art School, where he studied drawing and painting, between 1868 and 1872. He had finally won the tempered approval of his father in his pursuit of a career in art. He travelled next to Holland (the first of several visits) in 1871 and by his own admission it was in Holland that he truly found his vocation as a painter. During his education he also yearned to work with Belgian painter Gustaf Wappers, who was well known as an expert colorist. He finished his first canvas in 1873 entitled Women Plucking Geese, which yielded considerable scorn within the art establishment who dubbed him the "apostle of ugliness." However, a buyer purchased the painting and Liebermann used the proceeds to fund a trip to Paris that same year.

Once in Paris, Liebermann became interested in the work of French Realist Gustave Courbet and made the acquaintance of Hungarian painter Mihály Munkácsy, whom he followed in manner for a short period. Liebermann also received news that renowned German artist Adolph Menzel requested a meeting with him. He greatly admired Menzel and upon his return from Paris, met with him. Liebermann also travelled to Barbizon, a small French village, where he encountered the Barbizon School and met with its founder Jean-Francois Millet. Though from sound bourgeois stock himself, Liebermann took on board Millet's noble socialist principles. However, whereas Millet tended to represent the rural working classes as heroic figures, Liebermann approached the same subjects without embellishment or unnecessary sentiment. After his return to Germany, Liebermann continued with his travels, spending summers in Holland, where he became fascinated by the slow-paced lifestyle and the atmospheric landscape.

Liebermann also travelled to Italy where he stayed in Venice for two months and met with Munich-based painter Franz von Lenbach. In 1878, he relocated to Munich, solidifying his status as a serious progressive artist. In the early 1880s, he enjoyed the culture and continued art patronage Munich had to offer, visiting museums and galleries and forming friendships that would last the rest of his life. He resettled in Berlin in 1884 and remained there until his death. He married Martha Marckwald in 1884. They parented one child, Marianne Henriette Käthe, in 1885.

Mature Period

During the 1890s Liebermann continued to live and paint in Berlin (spending his summers in Holland). Following the death of his mother in 1892, and his father soon thereafter in 1894, Liebermann was financially and emotionally liberated from his father's lingering trepidations about his status as an artist. He moved into his family home in Pariser Platz (where he lived out the remainder of his life).

In 1898, Liebermann became the President of the Berlin Secession, an art club that was founded as an alternative to the conservative Prussian Art Association. It was formed of sixty-five Berlin artists who sought to digress from traditional and academic art and was instrumental in Berlin's transition from imperial metropolis to an artistic hub during the turn of the century. It followed secession groups in France (better known as the "Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts"), Munich and Vienna. The most influential of these was the Vienna Secession founded in 1897 and led by the great Symbolist painter Gustav Klimt. The group placed strong emphasis on architecture and design and played a major part in the burgeoning Art Nouveau movement and the flowering of modern design. Later on, the Vienna Secession attracted the likes of Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka, two of the greatest exponents of Expressionism.

The art of Germany was strongly affected by the Secession, moving towards more modern and progressive art styles including Art Noveau and Impressionism. However, German art was not generally influenced by the French impressionists, and Liebermann was one of the leading proponents of Impressionism in Germany having drawn on the paintings of Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas. However, because of rising anti-Semitism in Germany, Impressionists such as Liebermann, Max Slevogt, Lovis Corinth and August von Brandis stood accused of transposing international ideas into German art. Liebermann's art and life during the time of the Secession was thus riddled with inner conflict between his conservative Prussian upbringing, his Jewish heritage, and his admiration for international art styles. This was most evident after Liebermann organized a politically courageous show of new German art, for which was awarded the French Legion of Honor, though in the event, the repressive German government would not let him travel to France to accept the award.

Despite the interference of the state, Liebermann persevered, bringing Berlin to the forefront of the art world as founder and leader of the Verein der Elf (Club of Eleven) and furthered the reach of the Berlin Secession. However, he also maintained mainstream relevance through his extensive network of artistic contacts, and in 1897 the very traditional Prussian Academy of Art recognized his fiftieth birthday with a major art exhibition. His art thus came to represent both the past and future of Berlin art.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, Liebermann's range of artistic subjects became more constricted as he focused more on portrait and still-life representations. He remained a prominent Berlin artist, but he was not the same champion of modernism and artistic progression that he was prior. Because of Liebermann's French associations, he still had numerous confrontations with Prussian conservatives and government officials. Yet despite his involvement with German politics, Liebermann's output remained constant; between 1900 and 1910 he averaged 28 oil paintings per year in addition to numerous sketches, prints, lithographs and pastels.

Late Period

Due to his career success at the turn of the century, Liebermann had become a part of Germany's wealthiest echelon. In 1909, he purchased land on the Wannsee lake with his own earnings. There he built a stately home and called on the lush scenery for artistic inspiration. However, he was still subject to criticism within Berlin and in 1911 he resigned as President of the Berlin Secession. After the outbreak of World War I (in 1914) Liebermann, with a number of other painters, decided to try to work with the government to uphold cultural unity in Germany and to help promote victory on the warfront. Liebermann did so by contributing to a journal entitled Kriegszeit (Wartime) that was issued by his friend Paul Cassirer. He contributed to the journal for several years, creating lithographs and fostering German patriotism and unity.

At the end of World War I, Germany and its art scene was emaciated. Liebermann had hoped that in the wake of military defeat, Germany would become a more liberal society. He was indeed a proponent of liberalism and sparked debates in order that political, cultural and ethical disagreements might result in civilized dialogue. However, because of his intellectual focus he was (mistakenly) thought of by many as elitist. Nevertheless, for his eightieth birthday, Liebermann held a party for one hundred guests at Wannsee's Swedish Pavilion, where he was presented with the key to Berlin by the mayor. In 1933, as the Nazis Party intensified their scrutiny of him, Liebermann resigned his post as president of the Academy. Soon after, the Gestapo began removing his paintings from museum walls and confiscating them from private collections. Deeply affected by the menacing shift in German politics, he withdrew from public life but continued to paint his gardens, self-portraits and portraits of family members until his death in his Pariser Platz home in 1935.

The Legacy of Max Liebermann

Liebermann is regarded by many as one of the most instrumental proponents of artistic and political modernism in Germany. He has been cited alongside Courbet, Monet, Manet and Degas as an important member of early modernism and Impressionism in Europe. His technique, artistry and talent were admired throughout the 20th century. Meanwhile, some of his most notable achievements have been in his role as a cultural spokesperson. His input had allowed Berlin to become an influential art hubs at the turn of the 20th century. In fact, in 2005 Mason Klein, the curator of New York's Jewish Museum, stated that Liebermann's cultural leadership created a public artistic forum in which traditional and new art institutions were able to interact.

Despite being of a privileged background himself, Liebermann's work was also praised by officials of the German Democratic Republic during the mid-20th century for its honest depictions of rural labor. He has had numerous commemorative exhibitions - Liebermann's work can be found in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris - and his villa in Wannsee was converted in 2006 into a museum which also holds exhibitions. Liebermann's work has also been regarded as seminal for the development of Impressionism in Germany and Europe, and he remains a prominent figure within the pantheon of modern European artists.

Despite being highly regarded amongst his peers, and a VIP within the German artistic community at large, his death went unreported by the press which was now under Nazi control. Consequently, his funeral passed without representation from the Prussian Academy of Arts. Yet despite taking place under the close scrutiny of the Gestapo, more than 100 guests attended his funeral including Hans Purrmann, Otto Nagel, Bruno Cassirer, Georg Kolbe, and Adolph Goldschmidt.

Influences and Connections

-

![Édouard Manet]() Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet -

![Edgar Degas]() Edgar Degas

Edgar Degas -

![Frans Hals]() Frans Hals

Frans Hals -

![Gustave Courbet]() Gustave Courbet

Gustave Courbet - Adolph Menzel

-

![Jean-François Millet]() Jean-François Millet

Jean-François Millet - Mihály Munkácsy

- Lovis Corinth

- Max Slevogt

- Ernst Oppler

- Fritz von Uhde

- Jozef Israëls

Useful Resources on Max Liebermann

- Max Liebermann: Modern Art and Modern GermanyOur PickBy Marion F. Deshmukh

- Max Liebermann: Pathfinder of German SecessionistsBy Anna Louise Wangeman