Summary of Medium Specificity & Flatness

Since the Enlightenment era, philosophers and art critics alike have ruminated on the unique aspects that separate the arts from each other. For some, the shared qualities of painting, sculpture, literature, and theater diminished the singular power each potentially held. Advocates for medium specificity demanded that each art concentrate on that which made it unique. In painting's case, it was its "flatness" that made it distinct from the others.

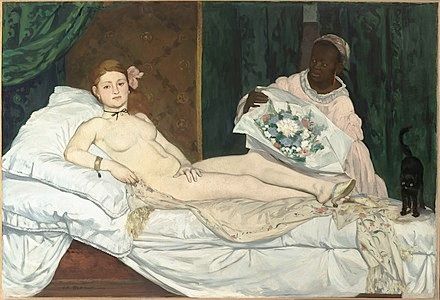

While ideas of medium specificity circulated among modern artists and critics alike, it was the American critic Clement Greenberg who gave a prominent voice to these ideas. In Greenberg's estimation, the postwar movement of Abstract Expressionism, and later Post-painterly Abstraction, was a further culmination in painting's self-analysis that began with Édouard Manet, bringing the viewer's attention to the surface of the painting and its material support.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Beginning in the second half of the 19th century, many artists and critics felt that for painting to be relevant to modern life, it needed to throw off the tradition of illusionistic depth and historical narrative and instead re-establish the flat surface of the canvas. Painting was no longer an illusionistic window to look through but an announcement of its construction out of canvas and paint.

- Greenberg did not consider abstraction to be an artistic style, but the specific nature of painting itself, as the artist emphasizes the two-dimensional flatness of the canvas and the paint represents nothing other than paint. He felt that a painting that included narrative content or figuration had been invaded and weakened by literature or sculpture.

- Greenberg argued that painting required an "escape from ideas," to maintain its medium specificity. The artwork and the critic were required to reject or dismiss biographical connection, social and political purpose, and cultural or philosophical associations.

- Greenberg's style of criticism - focusing on the formal aspects of the work of art - has its source in Enlightenment-era thinking and owes much to the teachings of Hans Hofmann. Subsequently, Greenberg's insistence on attending to compositional arrangement and relationships and not on biography or cultural context was widely influential for younger critics, although many critics and historians have questioned the narrow focus.

The Important Artists and Works of Medium Specificity & Flatness

Full Fathom Five

Clement Greenberg came to prominence as a critic during and after World War II as he was championing the Abstract Expressionists and, in particular, Jackson Pollock, who in 1947 embarked on his infamous drip paintings. In his 1948 essay, "The Crisis of the Easel Picture," Greenberg introduces the term "all-over" to describe a manner of handling pictorial space and surface in paintings, an approach he sees as an emerging tendency in American abstract art. For Greenberg, Pollock's drip painting were the epitome of the all-over technique, which continued Modernist painting's evolution toward flatness and its emphasis on its material support. According to Greenberg, the "'decentralized,' 'polyphonic,' all-over picture which, with a surface knit together of a multiplicity of identical or similar elements, repeats itself without strong variation from one end of the canvas to the other..." The picture was dissolving into "sheer texture, sheer sensation." Greenberg argued that this answered to "something deep-seated in contemporary sensibility. It corresponds perhaps to the feeling that all hierarchical distinctions have been exhausted, that no area or order of experience is either intrinsically or relatively superior to any other."

Pollock created a web of paint skeins that extend over the entirety of the canvas. No single area is highlighted as more interesting than any other, and the viewer's eye roams over the whole surface. While there are discrete areas of interest found amidst the composition - nails, tacks, buttons, cigarettes, etc. - the overall effect was of utmost importance to Greenberg. The immediate sensation of the texture of the painting, of its seemingly infinite repetition - that it could continue beyond the edges of the canvas - constituted Pollock's breakthrough for Greenberg.

Oil on canvas with nails, tacks, buttons, key, coins, cigarettes, matches, etc. - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Return

This abstract painting shows uneven shapes of blue, brown, and gray, punctuated by red and green, against a pale blue and pink background that is opaque and yet atmospheric. The gestural and visible brushstrokes and the slashes of red and green create a sense of movement and, simultaneously, make the irregular shapes seem like a crowd of figures glimpsed on a street, the setting hazy behind them. Subtly, Guston undercuts both the flatness of the pictorial plane and its medium specificity, as the abstract work nonetheless suggests forms materializing out of something like a landscape, even as the physicality of his painting, the pigment applied from different directions, emphasizes the surface and plane of the canvas itself.

While Greenberg had championed Abstract Expressionism, by the mid-1950s he felt that the artists had gone astray, citing what he called "homeless representation" in the works of Pollock, Guston, and, particularly, Willem de Kooning. For Greenberg, the representational and quasi-representational compositions defeated painting's specificity by suggesting narrative content, which Greenberg had deemed anathema.

Eventually abandoning abstraction altogether, in the late 1960s Guston began creating figurative paintings that were more cartoon-like and teemed with humor, unrest, and disjunctions. Emphasizing his artistic independence, Guston directly challenged the concept of medium purity, then saying, "There is something ridiculous and miserly in the myth we inherit from abstract art: That painting is autonomous, pure and for itself, therefore we habitually analyze its ingredients and define its limits. But painting IS 'impure.' It is the adjustment of 'impurities' which forces its continuity. We are image makers, and image ridden."

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

The Conjurer

In this abstract painting, color itself becomes "the conjurer," as irregular forms materialize energetically in the spatial relationship between intense primary colors and white and black. Profoundly influenced by Hofmann's teaching and artistic practice, Clement Greenberg noted the "intensity of color" in his work, which he saw as the exemplar of what he called "American-Type Painting." In his essay of the same name published in 1955, he wrote, "By tradition, convention, and habit we expect pictorial structure to be presented in contrasts of dark and light, or value. Hofmann, who started from Matisse, the Fauves, and Kandinsky as much as from Picasso, rejected value contrast as the essential building block," in favor of color, creating "a fully chromatic art."

Hofmann was a formative influence upon Greenberg. The artist's belief that "each medium of expression has its own order of being" was foundational for Greenberg's insistence on medium specificity. Equally important was Hofmann's concept of "recreated flatness." Acknowledging that the application of paint disturbed the flatness of the surface, Hofmann felt that the artist's challenge was to achieve what he called "recreated flatness," as texture, form, and color created, interdependently, a spatial "push and pull." Importantly, this "push and pull" created an optical space, not an illusionistic space that one could imagine inhabiting. Greenberg acknowledged the artist's importance in 1955, when he wrote, "Over the past fifteen years, a body of painting has emerged in this country that deserves to be called major. Hans Hofmann's art and teaching have been one of its main fountainheads of style.'

Oil on canvas

The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, II

Part of the artist's pioneering series Black Paintings, The Marriage of Reason and Squalor employs a simple geometric pattern. The inverted U-shapes on each side are arranged concentrically around a central single line of unpainted, raw canvas. As the artist explained, the "regulated space" pushed "illusionistic space out of the painting at a constant rate." The impersonal flatness of the image and its simple, almost grid-like forms was a radical departure from gestural and emotionally tinged work of the Abstract Expressionists and reflected Stella's view of a painting as "a flat surface with paint on it - nothing more. "

Stella's series, emphasizing the painting as a flat object, had a notable influence on Minimalism, as it emphasized art as a material object with which the viewer interacted. This painting was made for MoMA's 1959 exhibition Sixteen Americans, where it was shown along with three of his other black paintings. At the time, Stella stated what became his most famous maxim, "What you see is what you see."

In his influential essays Michael Fried praised Stella for emphasizing the flatness of the painting's support, writing, "Stella's stripe paintings ... represent the most unequivocal ... acknowledgment of literal shape in the history of modernism." He saw the artist as representing "a new illusionism [that] both subsumes and dissolves the picture-surface."

Enamel on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

Gift

In Gift, concentric rings of white, blue, and two shades of green are centered in an off-yellow background. Varying in thickness, the rings both suggest a pattern and evade it, as the thickness of the white outer ring disrupts the pattern of the other rings that widen toward the larger light green orb at the center. Noland began making his target series in the late 1950s, as he concentrated solely on the formal device, while eschewing any hint of personal expression. In the early 1960s, Greenberg wrote, "Painterly Abstraction has collapsed because in its second generation it has produced some of the most mannered, imitative, uninspiring and repetitious art in our tradition." He felt Noland's work was a vital new direction putting "the main stress on color as hue . . . Harking back in some ways to Impressionism, reconciling the Impressionist glow with Cubist opacity." He aggressively promoted the artist's work, seeing it as a leading exemplar of a "newer abstract painting [that] suggests possibilities of color for which there are no precedents in Western tradition."

The two men first met in 1950 when Noland was studying at Black Mountain College and began taking Greenberg's advice, as he said, "I would take suggestions from Clem very seriously. More seriously than from anything else." This work, originally titled Clement's Gift, was a kind of homage to the critic's sensibility and taste, as Noland explained, "I think judgment's crucial ... and that has something to do with taste. Taste: we use it in the negative sense, but there is the best taste, you know. There's the right taste. There's the real taste." Greenberg hung this painting in his apartment, just above his desk, so that the monumental work dominated his study.

In 1963, Greenberg included this work in his exhibition, Three New American Painters: Louis, Noland, Olitski, where he used the shortened version of the title. Subsequently, he loaned the work for the 1964 Venice Biennale, where it was included with twelve other paintings by Noland. Noland's work was widely viewed as representing the traditional modernism and abstract painting that Greenberg promoted in contrast to the radical challenge of the proto-Pop Art of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, and critic Gene Baro described Noland's work as "more enshrined than exhibited." When Rauschenberg's work was awarded the Grand Prize at that year's Biennale, the moment was seen as marking the diminishment of Greenberg's primacy.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Beginnings

The debate about the limitations and defining character of art media originated in the 18th century, when German philosopher, art critic, and dramatist Gotthold Ephraim Lessing published Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry in 1776. The title referenced the famous classical sculpture Laocoon and His Sons (27 BCE-68CE), which depicted the myth of Laocoon and his two sons, killed by giant pythons sent in punishment by the gods. In his essay, Lessing viewed poetry as extending itself in time while painting extended itself in space. He wrote, "It is an intrusion of the painter into the domain of the poet, which good taste can never sanction, when the painter combines in one and the same picture two points necessarily separate in time." Lessing felt that because painting and sculpture were static, material objects, they could not truthfully represent narratives that happen over time. Clement Greenberg noted Lessing's work as being the first to recognize "the presence of a practical as well as a theoretical confusion of the art."

By the 19th century, a number of implicitly modern trends developed as artists and critics in various disciplines attempted to establish the characteristics of specific art disciplines. Since the time of Plato and Aristotle the Western tradition had most valued representational art that served a moral and philosophical purpose, but newer, modern trends, responding to rapidly changing industrial societies, reflected the search for art's value outside of representation. In this quest, many began to argue that art had value in and of itself, independent of social, political, religious, or historical purposes. The art-for-art's-sake attitude is often attributed to the writer Théophile Gautier who used it as the epigraph for his novel Mademoiselle de Maupin (1835), though it was also widely employed by a number of writers, including Benjamin Constant, Victor Cousin, and Edgar Allan Poe, before being adopted by the writers Aubrey Beardsley and Walter Pater.

Often artists and critics relied on the musical analogies to argue for art's autonomy. American-born artist James McNeill Whistler argued, "Art should be independent of all clap-trap - should stand alone." Because music was understood as non-representational, it offered a model for painting in its search for autonomy. To emphasize this point, Whistler began titling his paintings with musical terms, such as nocturne, symphony, harmony, study, and arrangement. Ironically, in yoking painting to music, Whistler, in fact, undermined painting's autonomy, but for him and others, their insistence on the musical analogy was a means to re-think what painting could be. In titling his paintings, he emphasized the color and tones of his composition instead of the representational subject matter. By naming a portrait of his mother Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1 (1871), Whistler de-emphasized the subject matter - what is represented - and encouraged the viewer to concentrate on the formal aspects of how the subject is composed.

Recognizing this history, the American art critic Clement Greenberg, one of the most well known and respected critics in the U.S. in the 20th century, thought it was with the Impressionist painters, and in particular Édouard Manet's scandalous painting Olympia (1863), that artists began to emphasize the flatness of the pictorial plane. Greenberg noted, "Modernism [starting with Manet] used art to call attention to art." In his depiction of the prostitute as the modern-day Venus, Manet's use of a dark outline around the woman's body and the visibility of the brush strokes, Manet calls attention to the flatness of the picture plane instead of illusionistic space. For Greenberg it was this flatness and not the subject matter - also with controversial socio-political implications - that made it one of the most radical paintings of its time.

Medium Specificity and Flatness in Abstract Art

After the Impressionists, artists such as Paul Cézanne, and later the Cubists, would continue the development of modern art. In the faceted compositions of Analytical Cubism, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque created ambiguous spaces in which background and forms merged, becoming almost indistinguishable. Later, artists like Piet Mondrian took abstraction to extreme ends, creating seemingly austere compositions with only horizontal and vertical black lines and blocks of primary colors. The intersecting black lines that structure Mondrian's composition recall two-dimensional grids, emphasizing not only the flatness of the picture plane but also the shape of the canvas, thus abolishing illusionistic depth.

Importantly the German-born artist Hans Hofmann absorbed this modernist tradition, and when he came to the United States in the 1930s, he taught countless young artists - and Clement Greenberg - these ideas. His ideas that "each medium of expression has its own order of being" and his concept of "re-created flatness" were a formative influence upon Greenberg, who noted how Hofmann's lectures in 1938 and 1939 "were a crucial experience" in his being "able to see abstract art." For Hofmann, once an artist applied paint to a canvas, the pristine flatness of the canvas was actually destroyed, as there was now a foreground - the mark - and a background - the canvas, but once the artist "destroyed" the flatness, he or she had to "re-create" it; that is, the modern artist could not rely on the illusionistic depth of foreground and background, but had to keep the focus on the surface of the canvas as a place for expression. For Greenberg, the emphasis on flatness, then, was ultimately more than just emphasizing painting's uniqueness among the arts, but was essential for the very possibility of expressing oneself in paint.

It was, of course, the Abstract Expressionist painters who quickly took this idea to heart, creating abstract compositions that emphasized the gesture or monochromatic swaths of color, which the artists insisted, were expressive of their own experiences, thoughts, and feelings.

Clement Greenberg's Championing of Modern Painting

Though earlier trends informed Medium Specificity and Flatness, the concepts became primary concerns among artists and critics after World War II. Greenberg defined medium specificity as "the unique and proper area of competence of each art [that] coincided with all that was unique in the nature of its medium." In other words, each art should concentrate on what set it apart from the other arts. He also called the concept medium purity, though he often used "pure" in scare quotes to indicate that absolute purity was impossible.

To achieve its independence as a medium, painting needed to be abstract, as Greenberg wrote, "to divest itself of everything it might share with sculpture, and it is in its effort to do this, and not so much - I repeat - to exclude the representational or literary, that painting has made itself abstract." In moving away from representational subject matter, painting would no longer attempt to create an illusionistic three-dimensional space that one could imagine inhabiting. Instead, in pursuing abstract forms, painting would emphasize its flatness.

Flatness, or what Greenberg described as the "literal two-dimensionality" of the canvas was considered the defining element of medium specificity in painting. As he noted, "flatness alone was unique and exclusive to pictorial art... the only condition painting shared with no other art." For Greenberg, the recent paintings of Jackson Pollock, with their swirling skeins of paint and lack of representational imagery, were the epitome of flatness. Later, he would also champion the works by other abstract expressionists, including Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, and Clyfford Still, whose Color Field paintings Greenberg argued set a new trajectory for painting.

Concepts and Styles

Flattening the Canvas Further: Post-Painterly Abstraction

After formalizing his thoughts on medium specificity and flatness in his 1960 essay "Modernist Painting" and his 1962 essay "After Abstract Expressionism," Greenberg's theories greatly influenced a group of artists centered in Washington D.C. The Washington Color School, as it came to be known, was first described as Post-Painterly Abstraction, from the name of a 1964 exhibition curated by Clement Greenberg at the Los Angeles Country Museum of Art. Its practitioners, including Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, and Jules Olitski, emphasized the planar field of the canvas. The artists used color, and not drawing, to create and delineate simple geometric forms, and they often spoke of wanting to put pure color on the canvas to create an immediate, all at once, visual experience for the viewer. This optical experience became more important than conveying subject matter. They also often left large portions of their canvases bare and untreated, further emphasizing the shape and flatness of the physical canvas. In eschewing the gestural approach of the Abstract Expressionists, their paintings seem impersonal, or at least not as expressive as their predecessors, but Greenberg heralded the new approach as one of "openness and clarity."

Minimalism-A New Approach to Medium Specificity

In the 1960s, a young critic and acolyte of Greenberg, Michael Fried praised the work of Olitski and Noland as well as the work of Frank Stella as exemplifying "a new illusionism [that] both subsumes and dissolves the picture-surface." According to Fried, the Post-Painterly artists used literal shapes on a flat surface in order to bring together canvas, shape and color into one unified whole, where each entity ceased to be independent. Put most simply, these artists achieved a complete flatness by eliminating the illusion of depth.

Frank Stella's work, emphasizing the shape of flat canvas by employing precise but uniform color, minimal detail, and a cool impersonal technique, had a formative influence on Minimalism. Several of Stella's paintings were significant in this regard because of their unique shapes. By fitting the canvas to the contours of the paintings' colors, Stella redefined the traditional support system and made paint itself the painting's form.

While Fried praised Stella's use of the shaped canvas and his emphasis on flatness, he felt that other artists were taking the emphasis on art's materiality too far. In 1967, Fried published "Art and Objecthood," a scathing indictment of Minimalism, or what he termed "literalist" art. In his estimation artists such as Donald Judd and Tony Smith were intentionally creating non-art. As he saw it, their approach exaggerated the material object of the work, focusing on an interactive experience for the viewer that he defined as "theatrical" and the "negation of art." In emphasizing the object and the viewer's physical interaction with the work, the "literalists" introduced a temporal element to art, aligning it more with the temporal experience of theater. "Art" and "objecthood" were viewed as opposing forces, and Fried felt that modern art, committedly resisted objecthood, while still emphasizing its medium specificity.

Further Developments

Greenberg's championing of medium specificity and flatness had an outsized influence on much postwar art and criticism, but he also had his detractors, including his rival critic Harold Rosenberg. Already in 1952, Rosenberg asserted, "The new American painting is not 'pure' art, since the extrusion of the object was not for the sake of the aesthetic. The apples weren't brushed off the table in order to make room for perfect relations of space and color. They had to do so that nothing would get in the way of the act of painting."

While many of the Abstract Expressionists welcomed Greenberg's championing of them in the press, most of them, including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Philip Guston, cared little for maintaining the purity of abstract forms in their work, and by the 1950s, they had fallen out of Greenberg's favor for including elements of figuration in their work. Subsequently, other artists, notably Robert Rauschenberg refuted medium specificity by creating what he called "combines," placing everyday objects such as blankets, glass, and miscellaneous hardware onto his painted canvases.

Critic Leo Steinberg, who was not a fan of Greenberg's formalist criticism, took the idea of flatness in an entirely new direction with his description of Rauschenberg's screen-printed collages as "flatbed picture planes." Steinberg wrote, "Rauschenberg's picture plane had to become a surface to which anything reachable-thinkable would adhere. It had to be whatever a billboard or dashboard is, and everything a projection screen is, with further affinities for anything that is flat and worked over - palimpsest, canceled plate, printer's proof, trial blank, chart, map, aerial view. Any flat documentary surface that tabulates information is a relevant analogue of his picture plane - radically different from the transparent projection plane with its optical correspondence to man's visual field." Here, Steinberg puts a cultural spin on the idea of flatness that had circulated through the 20th century, which is not so much about the flatness of the canvas but the flat screens and surfaces that carry the images we consume on a daily basis.

During the 1960s, artists concerned with Civil Rights, the war in Vietnam, a new feminist wave, and gay rights increasingly felt that the medium specificity championed by Greenberg and Fried was not up to the task to handle the cultural seismic shifts happening in U. S. society. Performance, Installation, and Video Art became more common as artists purposefully crossed artistic boundaries, blurring the distinctions between mediums and additionally insisted on the temporal nature of the work, which Fried had decried. In his influential essay accompanying the 1977 Pictures exhibition, Douglas Crimp argued that Fried's lament of the increasing importance placed on temporality, on the viewer's experience, came to dominate much of the art making in the last 30 years of the 20th century. In describing the likes of Cindy Sherman and Jack Goldstein, Crimp explained, "If many of these artists can be said to have been apprenticed in the field of performance as it issued from minimalism, they have nevertheless begun to reverse its priorities, making of the literal situation and duration of the performed even a tableau whose presence and temporality are utterly psychologized; performance becomes just one of a number of ways of 'staging' a picture."

Later critics such as W.J.T. Mitchell continued to oppose Greenberg's theory. In his influential 1989 essay "Ut Pictura Theoria: Abstract Painting and the Repression of Language," Mitchell criticizes the emphasis on the atemporal aspect of painting, its pure visuality, as a convenient myth that needs to be left behind.

Important Essays

“Towards a Newer Laocoon”

By Clement Greenberg

Originally published in Partisan Review, 1940

With the word "Laocoon," Greenberg referenced two sources: Gotthold Lessing's 1766 "Laocoon: An Essay Upon the Limits of Poetry and Painting" and Irving Babbit's 1910 essay, "Laokoon: An Essay on the Confusion of the Arts." Greenberg particularly noted Lessing's work as recognizing "the presence of a practical as well as a theoretical confusion of the arts." While Lessing was primarily concerned with literature, Greenberg's essay undertook the critical debate of medium specificity in the arts.

In tracing the history of modern painting, Greenberg notes that in the past, various art forms imitated the art that was most prominent. In doing so, the "subservient arts" betrayed that which was unique to them, "concealing their medium," and according to Greenberg, "A confusion of the arts results." In this context, Greenberg stressed the importance of the "purist's" attitude toward art. He wrote that a "purist's" concern with art translates to "an anxiousness as to the fate of art, a concern for its identity. We must respect this." A desire for a "pure" form of art, therefore, is a desire for the survival of painting and sculpture, or plastic arts, in the face of mass-produced kitsch and entertainment. Additionally, Greenberg created the foundation for one of his more controversial positions in this essay, writing, "it is not so easy to reject the purist's assertion that the best of contemporary plastic art is abstract."

With this historical analysis, Greenberg understood abstraction as an "historical imperative," noting, "what I have written has turned out to be an historical apology for abstract art." In subsequent, future writings, Greenberg would go on to explain how Abstract Expressionism, what he preferred to call "American-Type" Painting, was not only the dominant art form of its day but the purest art form to have emerged in the modern era.

“Modernist Painting”

By Clement Greenberg

Originally published in Forum Lectures (Voice of America), Washington, D. C., 1960

Analyzing Modernism within the historical continuity of art, Greenberg wrote, "it includes almost the whole of what is truly alive in our culture" and defined it as self-critical, "the characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself...to entrench it more deeply in the area of its competence."

Greenberg argued that the essential and unique element in Modern painting is its flatness. As he wrote, "Flatness, two-dimensionality, was the only condition painting shared with no other art, and so Modernist painting oriented itself to flatness as it did to nothing else."

The limitations of painting, which he defined as "the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of pigment...were treated by the Old Masters as negative factors that could be acknowledged only implicitly or indirectly." In contrast, "Modernist painting has come to regard these same limitations as positive factors that are to be acknowledged. Manet's paintings became the first Modernist ones by virtue of the frankness with which they declared the surfaces on which they were painted."

He also paid close attention to Cubism as a defining moment for flatness in Modern art. Artists like Picasso and Braque used the canvas plane to create spatial ambiguity, a representation of form without a clear and singular perspective. Greenberg wrote, "the Cubist counter-revolution eventuated in a kind of painting ...so flat indeed that it could hardly contain recognizable images."

Greenberg did concede that "the flatness towards which Modernist painting orients itself can never be an absolute flatness." He wrote, "The first mark made on a surface destroys its virtual flatness, and the configurations of a Mondrian still suggest a kind of illusion of a kind of third dimension. Only now it is a strictly pictorial, strictly optical third dimension." Perhaps drawing from Hans Hofmann's idea of "push-pull," in which forms and colors naturally shift from foreground to background based on their relationships to one another, Greenberg emphasizes the optical aspects of painting instead of its physicality.

“Art and Objecthood”

By Michael Fried

Originally published in Artforum, September, 1967

In the mid-1960s, Minimalism was seen as an alternative to the high drama of Abstract Expressionism, but Michael Fried was suspicious of Minimalism's foundations. Fried wrote his essay, "Art and Objecthood," in response to the work and theory of Minimalists Donald Judd, Robert Morris, and Tony Smith, whom he deemed "ideologists" and "literalists." He accused these artists of creating objects rather than autonomous works of art. With an emphasis on the viewer's physical interaction with work, literalist art demanded the viewer's attention, which Fried referred to as its theatricality.

Fried acknowledged that Minimalists like Judd and Morris challenged the ways in which the viewer developed a relationship to the object. In his view, modern art, insisting on its autonomy, sought "to defeat or suspend its...objecthood." For Fried, art and objecthood were opposing forces, and in reveling in its objecthood, Minimalism could not be art.

Fried also argued "theater is now the negation of art." His concluding points insisted on medium specificity and the separation of the arts. Fried argued, "The success, even the survival, of the arts has come increasingly to depend on their ability to defeat theater," and that "art degenerates as it approaches the condition of theatre."

Despite his ire for the sculptors, Fried felt that the Post-Painterly abstractions of Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, and Frank Stella, were aware of the importance of "shape" in painting. Stating "a conflict has gradually emerged between shape as a fundamental property of objects and shape as a medium of painting," Fried felt these painters successfully defended the medium of painting. Unlike the literalist who viewed "shape as a given property of objects," these painters viewed shape as a pictorial quality and thus, following Greenberg, held to the all-important self-criticality of the medium.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI