Summary of Willem de Kooning

One of the most prominent and celebrated of the Abstract Expressionist painters, Willem de Kooning's pictures typify the vigorous, gestural style of the movement. Perhaps more than any of his contemporaries, he developed a radically abstract style of painting that fused Cubism, Surrealism and Expressionism. While many of his colleagues moved from figuration to abstraction, de Kooning always painted figures, most notably women, and abstractions concurrently, making no distinction between the art historical categories. De Kooning's real subject, he insisted, was space and the figure-ground relation.

De Kooning fused abstraction, figuration, and landscapes in various ways throughout the many long decades of his career, and his unceasing journey to find new forms and subjects made his overall output more eclectic than most of his colleagues. His engagement with popular culture was also unique and informed a host of post-war artists from the Neo-Dadaism of Robert Rauschenberg to the Pop Art of James Rosenquist, and younger painters such as Cecily Brown have explored the gestural eroticism of his later paintings.

Accomplishments

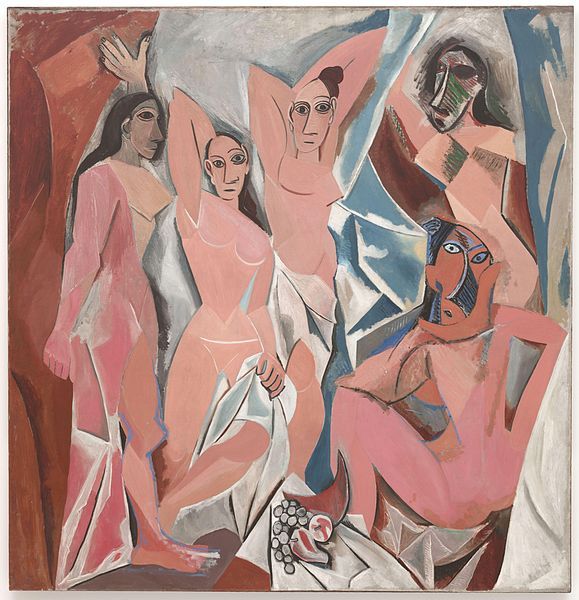

- Unlike most of his colleagues, de Kooning never fully abandoned the depiction of the human figure. His paintings of women feature a unique blend of gestural abstraction and figuration. Heavily influenced by the Cubism of Picasso, de Kooning became a master at ambiguously blending figure and ground in his pictures while dismembering, re-assembling, and distorting his figures in the process.

- Although known for continually reworking his canvases, de Kooning often left them with a sense of dynamic incompletion, as if the forms were still in the process of moving and settling and coming into definition. In this sense, his paintings exemplify Harold Rosenberg's definition of Action Painting - the painting is an event, an encounter between the artist and the materials, rather than a finished work in the traditional sense.

- Although he came to embody the popular image of the macho, hard-drinking artist, de Kooning approached his art with careful thought and was considered one of the most knowledgeable among the artists associated with the New York School. He possessed great facility, having been formally trained as a young man, and while he looked to the Modern masters like Picasso, Matisse, and Miró, he equally admired the likes of Ingres, Rubens, and Rembrandt.

The Life of Willem de Kooning

De Kooning’s drinking was nearly as prolific as his art making. He would drink until he had blackouts and a doctor warned him that his nervous system could be affected. In fact, de Kooning’s consumption of alcohol cost him his marriage as well as his mental and physical health.

Important Art by Willem de Kooning

Seated Woman

Seated Woman evolved out of a commission for a portrait. Around this time, Elaine Fried (they were not yet married) often modeled for de Kooning (one can see a resemblance of her, in the auburn-colored hair). The woman, wearing a low-cut yellow dress, sits on a chair with one leg crossed over the other. One arm rests in her open lap while the other seems to bend up toward her face, although there is no hand attached to it. As curator John Elderfield points out, all of her body parts, which seem more like shapes, float around her body, not quite connected to one another. De Kooning wrote in the early 1950s, "With intimate proportions I mean the familiarity you have when you look at somebody's big toe when close to it, or a crease in a hand or a nose - or lips or a ty [thigh]. The drawing those parts make are interchangeable one for the other and become so many spots of paint or brushstrokes." Given the struggles de Kooning had with painting certain body parts, it makes sense that he would reduce them to so many shapes, flipping, rotating, and using them in various contexts.

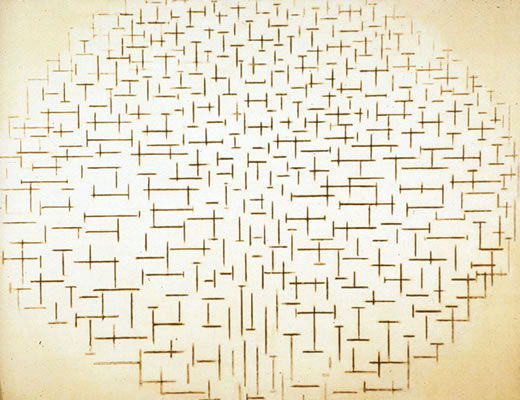

One can also see de Kooning's artistic influences on display in this painting. The fractured form of the figure certainly recalls Picasso, but Arshile Gorky's The Artist and his Mother (c.1926-c.1942), with all of its erasures and seemingly unfinished state, is also evident. The background of oranges, greens, and blues has been scraped down many times, creating a smooth, almost jewel-like surface. The planes of color hint at a Cubist space but also Mondrian's Neo-Plastic paintings. The squares also suggest the artist's studio walls, with various canvases tacked and piled against the wall. Coming on the heels of a series of paintings of seated men, Seated Woman (c.1940) can be seen as a companion piece and was de Kooning's first major painting of a woman, a subject to which he would continuously return over the decades.

Oil and charcoal on masonite - The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Pink Angels

In Pink Angels, pink- and coral-colored, biomorphic shapes float above and meld with a background of mustard yellows and golds, and the painting marks an important stage in de Kooning's evolution from figuration to abstraction in the later 1940s. The fleshy pink shapes evoke eyes and other anatomical forms that have been torn apart or are in the process of colliding. Certainly the carnage of World War II would not have been far from his mind, but curator John Elderfield has also pointed out connections to Picasso's Guernica as well as Miró, Matisse, and Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Importantly, de Kooning resisted disguising the process of the painting's making. Throughout the composition, charcoal lines outline the pink forms and intersect the golden areas. One sees an eye, perhaps part of a fish head, in the bottom left corner, and a circle and rectangle in the bottom center next to a crab-like form in the bottom right. De Kooning would often draw shapes onto paper and then trace them onto the canvas. As Elderfield describes, "He was continuing to use tracings to position and reposition drawn shapes beside and above each other on the canvas as he worked, a technique that indubitably helps to account for the complex layering and sudden, shifting dissonances that animate the work's surface." While most of the Abstract Expressionists denied that they made sketches for their paintings and instead worked spontaneously, de Kooning created a method that allowed for fluid construction and reconstruction of his compositions, leaving them still with an aura of spontaneity.

Oil and charcoal on canvas - Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation, Los Angeles

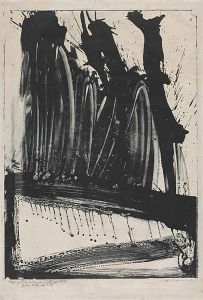

Untitled

De Kooning was already forty-four years old when he had his first solo exhibition at the Charlie Egan Gallery in the spring of 1948. Most of the paintings in the exhibition resembled Untitled - compositions painted in black and white, with vaguely recognizable shapes and complex plays of figure and ground. The show was little noticed in the press, but it jolted the artists of the downtown scene - old timers and newcomers alike. With the reduction of the color palette to stark black and white, de Kooning's play with surface and depth are amplified and unstable, creating a dynamic composition that threatens to break apart.

While one might observe a haunch or a penis, there is also something calligraphic about the white lines de Kooning draws on the surface, and one is reminded that he was a sign painter at one point in time. There was much interest in the time among the Abstract Expressionists about symbols and ideographs and how paintings might communicate a universal human emotion or experience. De Kooning's friend Harold Rosenberg described these paintings, calling them "symbolist abstraction dissociated from their sources in nature[;] organic shapes are carriers of emotional charges in the same category as numbers, mathematical signs, letters of the alphabet; the memory of a friend may be aroused by a pair of gloves or a telephone number, an erotic memory by a curved line or an initial." And, indeed, the shapes and signs enact a sort of mysterious drama that seems to be constantly shifting, making the viewer constantly adjust and see anew.

Oil and enamel on paper mounted on composition board - The Art Institute of Chicago

Excavation

Even as he returned to figuration in the late 1940s, he embarked on another abstraction, Excavation at the same time. Just over six-and-a-half-feet tall and eight-feet wide, Excavation is not as monumental as some later Abstract Expressionist paintings, but it is the biggest painting de Kooning ever made. The pictorial space de Kooning depicted on the canvas was closely tied to his own embodied sense of space in the physical world. In a talk he wrote for the Artists' Club, de Kooning explained, "If I stretch my arms next to the rest of myself and wonder where my fingers are - that is all the space I need as a painter." In other words, de Kooning's canvases are born at the fullest extension of his arms, where his fingers hold the brush that touches the canvases. To move beyond this scale one risks losing the human intimacy of the space.

The bulk of the surface is covered with dirty white, cream, and yellowish shapes outlined with black and gray lines. Throughout the canvas, one sees passages of crimson, blue, magenta, gold, and aqua. The effect is an all-over composition with no single point of entry and which draws the viewer's eyes across the entirety of the canvas. No one section stands out a more important or less interesting than another. That being said, one does see something of a ground line at the bottom of the edge of the painting and a rectangle that evokes a door or a window. Just as the composition seems to expand beyond the edges of the canvas, de Kooning brings the viewer back to a threshold, suggesting a particular place and time, grounding them in the present. Harold Rosenberg commented on the painting, "For all the protracted agitation that produced it, Excavation was a classical painting, majestic and distant, like a formula wrung out of testing explosives. If, as de Kooning liked to say, the artist function by 'getting into the canvas' and working his way out again, this masterpiece had seen him not only depart but close the door behind him."

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

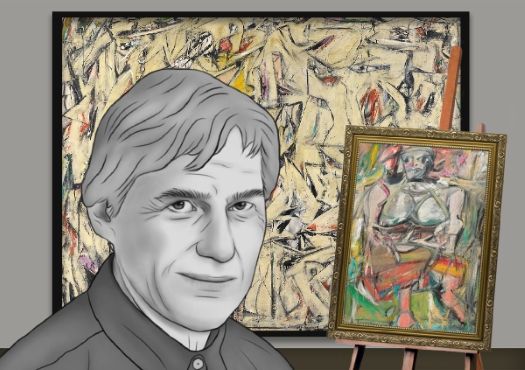

Woman III

Woman III belongs to the series of Women paintings de Kooning showed at the Sidney Janis Gallery to much outrage and controversy within the art world. The surface of the canvas is covered in thick swathes of energetic, vertical, and horizontal gestures of creamy and silvery hues. From this frantic surface, the figure of a wide-eyed, large-breasted woman emerges. She sports blond hair and a big smile. The compactness of the figure gives the sense of the body being squeezed or constrained, but at the same time, its gestural quality gives it a sense of wound-up energy. The slight tapering of the figure towards the knees and ankles is reminiscent of prehistoric figurines and Cycladic idols, precedents of the importance of the female form in art to which de Kooning often alluded. Importantly, de Kooning blends the figure and ground together, making it difficult to discern where one begins and ends, hence the woman both dissolves into and emerges from the background, an effect that de Kooning termed "no-environment." In the Women paintings from the early 1950s, we begin to see the ways in which body and landscape will merge in his later paintings.

The theme of women was one that de Kooning returned to regularly. Some cited his rocky relationship with his wife, his estranged relationship with his mother, and his penchant for womanizing as the source for the subject. Some went so far to say that de Kooning must hate women because, in this instance, he used smears of red paint to depict three bullet holes across her chest, but de Kooning responded to the accusation by saying, "I thought it was rubies." Elaine de Kooning clarified, explaining, "The bullet holes, be it known, are very chic rubies which stick to the skin unaided or abetted by pins or chains - a device de Kooning saw in Harper's Bazaar and never forgot."

While critics may have projected their own anxieties and misogynist tendencies onto the pictures, they missed the ways in which de Kooning engaged with and incorporated popular, consumer culture in his paintings. He often spoke of his women as being funny and larger than life, satirizing the shopping denizens of department stores and the fashionable ladies who paraded down Madison Avenue. He may have looked to ancient idols and classical odalisques, but de Kooning was equally intrigued with pin-up girls and movie stars. He was one of the only Abstract Expressionists to take on such subject matter, and for this reason he became an important touchstone for younger artists like Robert Rauschenberg, Larry Rivers, Grace Hartigan, and later Pop Artists.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Rosy-Fingered Dawn at Louse Point

At the end of the 1950s, de Kooning began to spend more and more time in East Hampton, a place far more rural and quieter than the bustling streets of New York City. In Rosy-Fingered Dawn at Louse Point, we see the quintessential bold strokes de Kooning had become known for, but the color palette and arrangement seem unlike what had come before. Curator John Elderfield refers to the new palette as "rococo hues of pink, yellow, and blue" and links it to his recent trip to Italy. The bright, pastel nature of these colors evokes a brighter landscape and reflections of water. Louse Point was a section of beach not far from where de Kooning was building his new studio, and Rosy-fingered dawn is a reference to Homer's epic The Odyssey. The reference also draws one's attention to the pink forms, which are also reminiscent of de Kooning's various forays with his women figures. While there is no form reminiscent of the figure or of landscape, for that matter, one thinks of de Kooning's quotation, "The landscape is in the Woman and there is Woman in the landscape."

The surface of the painting is quite varied. There is a lushness throughout, but parts are heavily impastoed, where de Kooning applied the paint thickly, while other parts are dry and thin where de Kooning pressed newspaper onto the surface to absorb the excess oil. Elderfield also points out that drips of paint run in multiple directions, suggesting that de Kooning worked on the canvas from multiple vantage points before settling on its final orientation. Such flexibility and open-endedness speaks to de Kooning's spontaneity and his desire to not pin any one form or composition down before it was ready.

Oil on canvas - Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

Woman and Child

It did not take long after de Kooning moved to Springs, East Hampton, that he again took up the figure. While he was still very much interested in pin-ups and pop stars, he also turned his attention to those who lived near him and frequented the beaches. Here, in Woman and Child, we see the pink flesh and breast of a woman whose knees are drawn up and touching each other. Perhaps she is lying on her back with her knees in the air. A goggle-eyed, orange-haired figure, presumably the child of the title, lies next to her, or perhaps the child is sitting. Of course, though, the title recalls the titles given to traditional depictions of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child, an allusion de Kooning was surely aware of. In a radical gesture, de Kooning makes the heavenly and spiritual fleshy and material.

De Kooning distorts the perspective and the figures to such a degree that the space of the painting becomes utterly ambiguous. As in his earliest Women paintings from the 1940s, body parts assume shapes and lives of their own, quite apart from where they are supposed to be. The increasingly abstract figure will completely dissolve, once again, into large, gestural, all-over abstract compositions in the 1970s.

Many decried these paintings as being out of step with the times. Their over-sweet pink and pastel hues, their lush and seemingly excessive gesturalness, and their exuberance contrasted sharply with the coolness of Color Field Painting, Minimalism, and Pop Art of the time. Some also felt uncomfortable with a man of de Kooning's age engaging in such overt eroticism. Despite these concerns, de Kooning was at the height of his fame in the 1960s, with collectors and museums alike wanting to acquire his paintings.

Oil on paper mounted on canvas

Untitled VI

By the end of the 1970s, de Kooning was struggling not only with his own drinking and depression but with his familiar process of all-over paintings as well; he was looking for a new way of painting. A friend recalled about the artist at that time, "What [de Kooning] would like to do now would be very 'free,' and he gently waves his hands in the air. He thinks about Matisse's La Danse." In some ways, even as he was trying to find a new path, he returned to old ways. The surface of Untitled VI is both thickly and sumptuously painted in parts and thin and scraped down in others. One sees evocative shapes, layers, and sharp juxtapositions.

The wispy ribbons of red and blue seem to blow across the white surface of the canvas, suggesting shapes, eddies, and doodles. The white, negative space between the lines suddenly becomes solid and equally suggestive, a play with figure and ground always at the heart of de Kooning's work. One of de Kooning's studio assistants from the time recalled that the forms in his paintings from the 1980s were often inspired by his earlier paintings, explaining that he looked at photographs of the older paintings and simplified their forms and lines "so that the new paintings are distillations of the old ones."

After de Kooning stopped painting in 1990, many looked to these later paintings suspiciously, as if they were too indebted to a team of studio assistants who were covering for an ailing artist, but when one considers them in relation to his earlier work, the paintings from the 1980s are an elegant and playful evocation of his entire career.

Oil on canvas - Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Collection

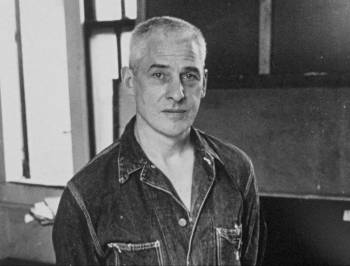

Biography of Willem de Kooning

Childhood and Education

Willem de Kooning was born in Rotterdam in the Netherlands in 1904, and his parents divorced when he was three. His mother, Cornelia Nobel, ran a bar and largely raised de Kooning on her own. He found his artistic vocation early and left school when he was twelve to apprentice at a commercial design and decorating firm. He then went on to study at the Rotterdam Academy of Fine Arts and Techniques. During this period, de Kooning became interested in Jugendstil, the German variant of Art Nouveau, and its organic forms were significant in shaping his early style; however, he was soon enamored with the ascendant Dutch movement De Stijl, becoming particularly interested in its emphasis on purity of color and form and its conception of the artist as a master craftsman.

After living for a year in Belgium in 1924, de Kooning returned to Rotterdam before travelling as a stowaway to the United States, arriving in Virginia in August 1926. He worked his way to Boston on a coal ship, then worked as a house painter in Hoboken, New Jersey, before moving across the Hudson River to Manhattan. There he took jobs in commercial art, designed window displays, and produced fashion advertisements, work which would consume him for several years. De Kooning was still unable to devote himself to the art he loved, but he found the community of artists in New York too valuable to leave behind; when offered a salaried job in Philadelphia, he remarked that he would rather be poor in New York than rich in Philadelphia.

Several artists proved important for his development in these early years. He valued the example of Stuart Davis' urbane modernism as well as John Graham's ideas, but Arshile Gorky was the biggest stylistic influence on de Kooning. He remembered, "I met a lot of artists, but then I met Gorky." Gorky had spent years working through Picasso's Cubism and then Miró's Surrealism before reaching his own mature style, and in subsequent years, de Kooning would follow a similar path; haunting the halls of the Metropolitan Museum as well as the Museum of Modern Art. He was impressed by two major exhibitions he saw at MoMA in 1936, Cubism and Abstract Art and Fantastic Art: Dada, and Surrealism, and he was powerfully influenced by a Picasso retrospective that was staged at the same museum in 1939.

Early Period

De Kooning worked on projects for the Works Progress Administration mural division from 1935 to 1937, and for the first time, like many American artists, he was able to focus his attention entirely on fine art instead of commercial painting. His network of friends expanded to include photographer Rudy Burckhardt, dance critic Edwin Denby, and art critic Harold Rosenberg, who became one of de Kooning's most ardent supporters, and in 1936, he was included in the show New Horizons in American Art at MoMA.

Men were often the subjects of his pictures during this period, and although they are often traditionally posed, the bodies of figures such as The Glazier (c.1940) were radically distorted and the planes flattened. De Kooning often struggled with certain details in his portraits - hair, hands, and shoulders in particular - which encouraged a habit of scraping down the paint and reworking areas of his pictures, which left them with the appearance of being unfinished. He also painted highly abstract pictures during this time, and these, such as The Wave (c.1942-44), are characterized by flat, biomorphic forms similar to those which had first attracted the young artist to Jugendstil.

In 1938, de Kooning took on Elaine Fried as a student; she became his wife in 1943, and in time, she would become a prominent critic and Abstract Expressionist in her own right. The two shared a tempestuous, alcohol-fueled relationship, and their marriage did not conform to traditional standards, each engaging in extramarital affairs. After several affairs, de Kooning had a child, Lisa, with one of his girlfriends, Joan Ward, and he and Elaine separated in the mid-1950s, though never officially divorced.

Mature Period

In the mid-1940s, De Kooning began a series of black and white abstractions, reportedly because he could not afford expensive pigments and had to turn to cheaper household enamels. With the pared-down color palette and the radical flattening of pictorial space, these abstractions, shown at the Charles Egan Gallery in 1948, portended the rise of Abstract Expressionism and were instrumental in establishing his reputation. He continued to work on them until the end of the decade, eventually allowing color to re-enter into later works such as Excavation (1950).

De Kooning is probably best known for his paintings of women. He worked on them over a nearly thirty-year period, starting in the early 1940s, yet they were first exhibited in 1953 at the Sidney Janis Gallery. At the center of this show was Woman I, a picture de Kooning began in 1950 and completed in the summer of 1952. The picture's process of creation was made famous not only by a series of photographs taken by Rudy Burckhardt, but also by Thomas B. Hess' article "de Kooning Paints a Picture," in which he described the process of the picture's creation as a voyage that involved hundreds of revisions, several abandonments and restarts, and was only completed minutes before the work was loaded onto the truck to go to the gallery.

Woman I was purchased from the Janis Gallery show by MoMA, which confirmed its importance in the eyes of many critics, yet the whole series of Women paintings became a controversial talking point for many other reasons. De Kooning's 1948 show had made him a leader of a new generation of painters, who seemed interested in suppressing narrative content and figuration in their paintings. Now de Kooning had reintroduced the figure, and some commentators - prominent critic Clement Greenberg included - felt it was a step backward.

While many saw de Kooning's figuration as an abrupt reversal, de Kooning always painted both figuratively and abstractly at the same time, and he dismissed these criticisms of returning to the figure. When asked about the controversy in 1960 by art critic David Sylvester, de Kooning replied, "In a way, if you pick up some paint with your brush and make somebody's nose with it, this is rather ridiculous when you think of it, theoretically or philosophically. It's really absurd to make an image, like a human image, with paint today, when you think about it, since we have this problem of doing or not doing it. But then all of a sudden it was even more absurd not to do it. So I fear that I'll have to follow my desires." De Kooning felt that one should not restrict oneself to certain ways of painting, since at the end of the day it's all paint on canvas, whether figural or abstract, so why not paint whatever one wants.

De Kooning's pictures were also controversial due to the expressive distortion of the figures and earned him the reputation for being a misogynist. Contrarian critic Emily Genauer wrote in Newsday in 1969, "[de Kooning] flays [the women], beats them, stretches them on racks, draws and quarters them.... It isn't the contempt in de Kooning's works that I mind, per se. It's the absence of wholeness and diversity in a great talent who seems to have chained himself to a leering, lynx-eyed totem pole." While many see something sinister in de Kooning's intentions, the pictures were, in part, inspired by fashionable women of the time and images of women in popular magazines. De Kooning explained to one interviewer, "In a way I feel that the Women of the '50s were a failure. I see the horror in them now, but I didn't mean it then. I wanted them to be funny and not look so sad and downtrodden like the women in the paintings in the '30s so I made them satiric and monstrous, like sibyls." Others defended the series as archetypes inspired by the work of ancient Mesopotamian idols, Old Masters, and modern artists. One of the most erudite among the New York School, de Kooning was steeped in art history, and he regarded Ingres's Odalisque (1814) as one of the major antecedents for the series; however he was also cautious about tracing the series' genealogy, saying "I don't paint with ideas of art in mind. I see something that excites me. It becomes my content."

De Kooning was a member of the Eighth Street Artists' Club, which met weekly to discuss art and ideas, and he also became a hard-drinking fixture at the Cedar Tavern. He had a very close working relationship with Franz Kline and was certainly the most powerful influence on the painter. He was less close to Jackson Pollock, though he admired him greatly and admitted to being jealous of his talent. He felt that Pollock possessed Michelangelo's terribilita, an ability to produce art of a sublime and awe-inspiring beauty. He once recalled, "a couple of times [Pollock] told me 'you know more, but I feel more.'"

Despite the controversies of the early 1950s, de Kooning's reputation continued to grow throughout the decade, and by the end of it, he found himself financially stable for the first time, buying land to build a studio in Springs, the small hamlet in East Hampton, where Jackson Pollock had lived and where other artists had flocked.

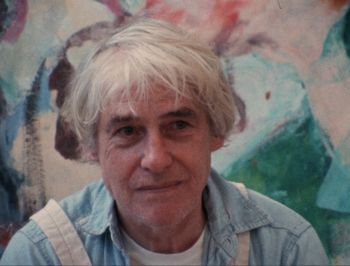

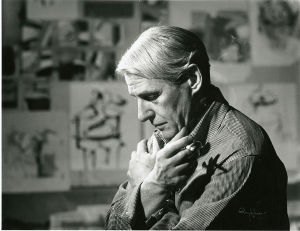

Later Years and Death

Thomas Hess described the settings for de Kooning's Women as "no-environment," indicating their ambiguous space, and his larger abstractions from mid-1950s seemed part and parcel of the gritty urban environment in which de Kooning lived. By the late 1950s, however, he was beginning to show interest in a new type of scenery. He began a series of Abstract Parkway Landscapes (1957-61), which were based on the landscape as seen from a moving car, and the Abstract Pastoral Landscapes (1960-66), explored his new environs in a more rural setting close to the water.

His personal life became correspondingly more settled. In 1962, he finally became an American citizen, after living in the U.S. for thirty-five years, and in 1963, he settled permanently in East Hampton, while he was finishing his large studio.

De Kooning's interests were moving away from the city, but they were not necessarily becoming any less radical. He had always looked to the Old Masters more than most of his peers, and even his Women series retained roots in traditional portraiture. His landscapes may have suggested tradition, yet they too were highly abstract and sometimes only referred to their inspiration in the title. They were characterized by bold, simple gestures similar to those of Franz Kline, with whom de Kooning had been very close. And although they have attracted less notoriety than the Women series, they proved highly influential, particularly on the work of the Californian painter Richard Diebenkorn's Ocean Park series.

On Long Island, de Kooning continued to paint women, but he also explored new avenues. In 1969 during a trip to Rome, de Kooning took up sculpture for the first time, and throughout the 1970s, he created works whose lumpy clay modeling was carried over into their cast bronze form. In 1968, de Kooning returned to Holland for the first time in forty-two years for his own retrospective at the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, organized by his friend Thomas Hess, which was also seen in London, New York, and Chicago.

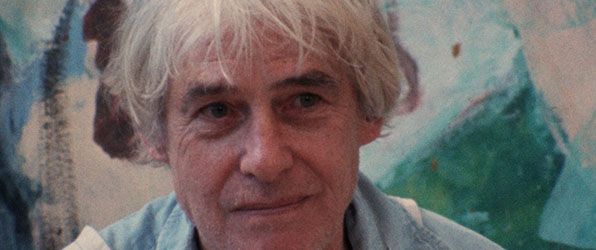

Living and painting on Long Island throughout the 1980s, de Kooning created large abstract works in bright tones with simpler, more restrained gestures than those that had characterized his earlier style. His work continued to attract high praise and looked like the work of an artist still in full charge of his talents. In the late-1970s, Elaine de Kooning returned to her husband's life to try to make him healthy after decades of hard drinking. By the end of the decade, de Kooning's memory began to be severely impaired, and he seemed to be suffering from Alzheimer's-like dementia. After Elaine de Kooning died in 1989, Willem came under the guardianship of his daughter, Lisa, until his death in 1997 at the age of 92.

The work he created in his last years has since prompted considerable debate about the nature of creativity. As de Kooning's prices continued to rise at auction, there was disagreement over whether his late works were compromised by his mental incapacity. Many argued, however, that - certainly as far as the Abstract Expressionists were concerned - creativity sprung more from intuition than intellect and that memory loss would likely not affect his ingrained motor functions such as using a paintbrush.

The Legacy of Willem de Kooning

While Jackson Pollock has been extolled as the most important and influential Abstract Expressionist and influenced the likes of Allan Kaprow, many young painters at the time found that appropriating Pollock's process of painting tended to produce paintings that looked like Pollock's, but de Kooning's use of color and gestural application of paint, as well as his disregard for divisions between abstraction and figuration, however, inspired countless painters and led critic Clement Greenberg to decry what he termed the "Tenth Street touch" that de Kooning spawned. With de Kooning's example, artists such as Larry Rivers and Grace Hartigan took figurative painting in new directions, and artists such as Al Held and Jack Whitten continued experimenting freely in abstraction. Even artists who attempted to distance themselves from the existential rhetoric surrounding de Kooning, including Robert Rauschenberg, who infamously took one of de Kooning's drawings, erased it, and eventually exhibited it as his own artwork (Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953)), found lessons in de Kooning's work.

The lush exuberance of his works from the 1960s and 1970s as well as the elegance of the paintings from the 1980s may not have received the same critical acclaim as his earlier work, but nevertheless, de Kooning's influence on painters remains important even to this day, particularly those attracted to gestural styles. The highly abstract and erotic work of prominent painter Cecily Brown is inconceivable without his example, and Amy Sillman has also recalibrated the macho histrionics associated with Abstract Expressionism in her contemporary paintings.

Influences and Connections

-

![Robert Rauschenberg]() Robert Rauschenberg

Robert Rauschenberg -

![Cecily Brown]() Cecily Brown

Cecily Brown ![Jack Whitten]() Jack Whitten

Jack Whitten- Amy Sillman

-

![Franz Kline]() Franz Kline

Franz Kline -

![Jackson Pollock]() Jackson Pollock

Jackson Pollock -

![Elaine de Kooning]() Elaine de Kooning

Elaine de Kooning -

![Thomas B. Hess]() Thomas B. Hess

Thomas B. Hess ![Milton Resnick]() Milton Resnick

Milton Resnick

-

![Abstract Expressionism]() Abstract Expressionism

Abstract Expressionism -

![Neo-Expressionism]() Neo-Expressionism

Neo-Expressionism - Contemporary painting