Summary of Donald Judd

Donald Judd was an American artist, whose rejection of both traditional painting and sculpture led him to a conception of art built upon the idea of the object as it exists in the environment. Judd's works belong to the Minimalist movement, whose goal was to rid art of the Abstract Expressionists' reliance on the self-referential trace of the painter in order to form pieces that were free from emotion. To accomplish this task, artists such as Judd created works comprising of single or repeated geometric forms produced from industrialized, machine-made materials that eschewed the artist's touch. Judd's geometric and modular creations have often been criticized for a seeming lack of content; it is this simplicity, however, that calls into question the nature of art and that posits Minimalist sculpture as an object of contemplation, one whose literal and insistent presence informs the process of beholding.

Accomplishments

- Judd's goal was to make objects that stood on their own as part of an expanded field of image making and that did not allude to anything beyond their own physical presence. As a result, his work, along with that of other Minimalist artists, is often called literalist.

- Unlike traditional sculpture, which was placed upon a plinth, thus setting it apart as a work of art, Judd's works stand directly on the floor and as a result, force the viewer to confront them according to their own, material existence.

- Judd combined the use of highly finished, industrialized materials, such as iron, steel, plastic, and Plexiglas - techniques and methods associated with the Bauhaus School - to give his works an impersonal, factory aesthetic. This served to separate his pieces from those of the Abstract Expressionists, whose emphasis on the artist's touch gave their images a confessional, personal context.

- Judd often presented his work in a serialized manner, a strategy that related to the reality of postwar, consumer culture as well as to the standardization and de-subjectifying nature of identical, multiple forms or systems. The multiple was another way to reinforce their materiality. This method was also seen as a part of a more general tendency toward the democratization of art, that is, to make art more accessible to more people, because it was composed of fabricated parts.

Important Art by Donald Judd

Untitled

This work represents one of Judd's early experiments in Minimalism: a freestanding, aluminum rectangle colored with brown enamel. By the 1960s, Judd had abandoned painting, having recognized that, "actual space is intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on a surface;" that is, he believed that a work that shares three-dimensional space with the beholder calls more attention to itself than an image that is hung on the wall. As an artist, Judd was beginning to recognize the importance of the environment to how a work is perceived. Here, he places a simple, rectangular form directly onto the floor of the gallery so that it demands recognition through its insistent materiality as well as through the fact that it impinges upon the viewer's passage through the space. The work, therefore, exists as an object rather than as something that belongs to the privileged and remote world of art. In this manner, Judd has begun to use a new visual language for three-dimensional form, one that emphasizes the simplicity and physical nature of the piece.

Enamel on aluminum, 55.9 x 127 x 95.3 cm - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Untitled

By the 1970s, Judd's "specific objects," as he liked to call these box-like forms that sat directly on the floor, had become, despite their sharp edges and flat color, more complex through his exploration of surface and color. The exterior surface is composed of copper, an industrial material, but one whose warm and reflective surface combines with the richness of the wooden floor as it mirrors its environment. The interior is colored with a highly saturated, red enamel that vibrates in its intensity and contrasts with the static nature of the form in its entirety. The red interior also contrasts with the copper, and yet deepens the viewers' experience by encouraging them to think about the relationship between inside and outside and by asking them to consider the effects of different surface values. Here, the sleekness of the red enamel adds to the seductive aspect of the piece, and may suggest some of the objects, like nail polish or cars, that we choose to purchase as consumers. Moreover, this piece is in some ways the polar opposite of the whole anthropomorphizing tendency that viewers have when they look at sculpture -- the tendency for humans to extend the vertical orientation of their own bodies and see human forms in sculpture, which traditionally was vertically oriented. Instead of seeing in the work a reflection of that usual vertical orientation of the human, organic form, here we have a piece that is more horizontal than vertical and contains inside it empty space rather than "insides" (internal organs).

Copper, enamel and aluminum, 916 x 1555 x 1782mm - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Untitled

This work is comprised of six identical, separate units with equal space in between each one. Although Untitled would seem to be part of a continuum, Judd believed that his works should be "seen as a whole" rather than as a composition of parts, and was convinced that color, shape, and surface created a unitary character; there is no hierarchy of forms or focal point as in more traditional works -- only repetition and rhythm created by the repetition. Here, Judd has begun working with Plexiglas and has combined it with a highly polished, reflective metal -- brass. This juxtaposition gives the viewer two very different experiences; on the one hand, the brass turns the observer's gaze outwards as it doubles both their own image and the space around them, while on the other, the transparent, yet richly colored Plexiglas draws the viewer's attention to the interior of the forms. The photograph of the work as reproduced here has been taken from an angle, but in actuality the viewer has a choice of point of view and distance from the piece. Changing either of these two variables changes the shapes and proportional relationships between the brass surfaces and those of the red Plexiglas. The viewer is also forced to confront the paradox of the unreal distortions reflected in the shiny brass surface versus the insistent reality of the units as things-in-themselves. Although the boxes are no longer placed on the floor, they still exist as objects in space, ones that impinge upon the viewer's own corporeal presence.

Brass and red flourescent Plexiglas, 6 units with 8 inch intervals, each unit 86.4 cm - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

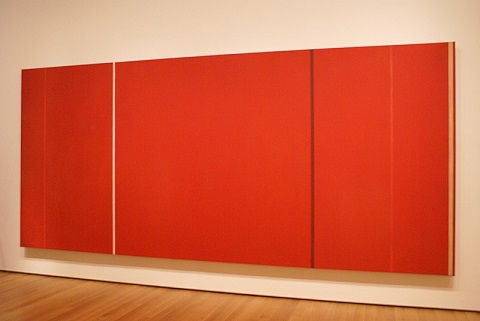

Untitled

By the 1980s, Judd turned to the creation of vertically-suspended stacks whose emphasis on the upright strongly suggests a repetition of the observer's own body, a fact that serves to create a strong and unique relationship between two material presences. The use of two different materials, aluminum and Plexiglas, again offers the viewer two experiences; from the front, the beholder is drawn into the murky depths of space, while from the side, the piece presents itself as opaque forms, jutting into space. Judd, himself, said that his works were, "neither painting nor sculpture" and in this manner, he has created an entirely new vocabulary for art.

Steel, aluminum and Plexiglas, 229 x 1016 x 787 mm

Untitled

The 15 concrete works that run along the border of the Chinati's property were the first works to be installed at the museum and were cast over a four-year period from 1980 through 1984. Each unit has the same measurements -- 2.5 x 2.5 x 2.5 meters -- and thus is large enough to enter. Here, the notion that the environment is an integral aspect of the work is taken to another level, where each box is both a permeable space as well as a monolithic whole. The neutral color of the concrete combines with the earth tones of the Texas plain, and the industrial nature of the forms seem intrinsically related to the abandoned air force base on which they are placed. Inspired, as well, by the Missouri landscape in which the artist was raised, these structures grow naturally out of both Judd's Minimalist aesthetic and from his early childhood years. In this work, he has achieved a full integration of form and space, art and environment.

Concrete - Chinati Foundation, Marfa Texas

Untitled

As a G.I., Judd had come across a military site in Marfa, Texas, which he later purchased with the help of the Dia Foundation in New York and which would eventually become the Chinati Foundation. These 100 milled aluminum rectangles form the center of the permanent collection. Each of the 100 rectangular forms, which are spread over two artillery sheds, has the same dimensions, yet the inside of each rectangle is unique. Although the configurations may seem arbitrary, Judd created them with the site in mind; as the viewer moves around the installation and the sunlight shifts throughout the day, the solid, aluminum boxes are transformed into ephemeral pieces and substance gives way to light. This is how the artist wanted these works to be seen. Judd had always been critical of the way his works had been displayed and with the creation of the Chinati, he was finally able to control all aspects of his work.

100 works in mill aluminum - Chinati Foundation, Marfa Texas

Judd Foundation: Judd's Restored Studio

In 1968, Judd purchased 101 Spring Street, a five-story cast iron building located in the Soho area of New York City. The building, constructed in 1870, was his home and studio and reflects his Minimalist aesthetic. As it contains Judd's own furniture designs and other artwork, the space has been dubbed the birthplace of the "permanent installation." It is interesting to note how the rectangular forms that predominate the interior, such as the tables, window frames and the planks of wood that make up the floor and ceiling are reflections of the grid-like forms that comprise the buildings and windows of lower Manhattan. As Judd said, "Art and architecture - all the arts - do not have to exist in isolation, as they do now. The fault is very much the key to the present society. Architecture is nearly gone, but it, art, all of the arts, in fact all parts of society, have to be rejoined and joined more than they have ever been." To this day the studio serves as one of the spaces where the Judd Foundation displays Judd's works.

101 Spring Street, New York

Biography of Donald Judd

Childhood

Donald Judd was born on June 3, 1928, in Excelsior Springs, Missouri. He spent much of his early childhood on his grandparents' farm and continued to live in the Midwest with his parents until they finally settled in New Jersey.

Early Training

Judd served in the United States Army in Korea and subsequently attended the College of William and Mary, the Art Students League in New York, and Columbia University, where he obtained a B.S. in Philosophy in 1953. He went on to work toward a master's degree in Art History, studying under such well-known scholars as Rudolf Wittkower and Meyer Schapiro. Between 1959 and 1965, he supported himself by writing criticism for major art magazines, such as Art News, and in 1968, he bought a five-story, cast-iron office building in Soho, which served as his New York residence and studio for the next 25 years.

In the late 1940s, Judd practiced as a painter and then shifted to the medium of the woodcut, whose linear qualities helped him move from figuration to abstraction. By the early 1960s, Judd had completely abandoned the two-dimensional picture plane and began to focus on three-dimensional forms in which the notion of materiality played a key role. In 1964, Judd wrote Specific Objects, a manifesto-like essay calling for a rejection of the residual, European value of illusionism and advocating an art based upon tangible materials. Judd aligned himself with other artists working in New York, such as John Chamberlain, Jasper Johns, and Dan Flavin, whose work also incorporated non-traditional materials such as found objects, steel, aluminum, and neon lighting. Like Judd, these artists had begun to recognize the physical environment as an intrinsic aspect of the work and that three-dimensional form was the most effective way to address spatial concerns.

Mature Period

By 1963, Judd's presence on the international art scene was beginning to take hold and his second solo show was held at the Green Gallery in New York. In 1966, the influential dealer Leo Castelli organized what would be the first in a long series of solo exhibitions for the artist, which ensured his prominence in the New York art scene. From 1962 though 1964, Judd worked as an instructor at Brooklyn College. Judd served as a visiting artist at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire in 1966 before going on to teach sculpture at Yale the following year. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Judd was the recipient of numerous grants and award from such institutions as the National Endowment for the Arts, the John Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, and the Swedish Institute. In 1968, the Whitney Museum of American Art organized the first retrospective of his work, an event that would establish his importance in the world of contemporary art.

In the early 1970s, Judd began to work on increasingly large and complex pieces, such as large, hollow boxes made of steel or copper, often colored with an enameled surface on the inside, which were placed directly on to the floor. By installing his works in this manner, Judd broke with the traditional manner of exhibiting three-dimensional art, which was usually placed on a plinth. Judd's strategy to erase the distance, both physical and psychological, between object and observer served to redefine this inter-relationship; rather than existing as a discrete work of art, Judd's structures form part of the environment and demand to be experienced as part of the viewer's own phenomenological existence.

Late Years and Death

In 1971, Judd rented a house in Marfa, Texas, whose desert surroundings resonated with the artist's aesthetic and which would form an antidote to his New York City studio. In 1979, with the help of the Dia Foundation, Judd purchased a 340-acre tract of desert land outside of the town, which included abandoned buildings from the former Army Fort D.A. Russell and on which he founded the Chinati Foundation, which opened in 1986. The landscape and wide-open spaces resonated with his Minimalist aesthetic. Judd was able to expand his visual language into larger forms, often using aluminum or concrete and integrating the works into the environment. In addition, the development of the Chinati Foundation gave Judd the opportunity to permanently install several large-scale works, according to his own aesthetic standards, as well as to create an exhibition space for other like-minded practitioners. In 1984 he also started to design furniture and expanded his materials to include anodized aluminum and acrylic.

The artist died of lymphoma on February 12, 1994, in New York.

The Legacy of Donald Judd

Donald Judd was a leader of the Minimalist movement and as such, helped to create an appreciation for the clean lines and uncluttered spaces often favored in interior design. By establishing the Chinati Foundation, Judd established a space that now serves as a museum, artist residency, and research center. In 1976, Judd began to turn his attention beyond Marfa and purchased land in Presidio County close to the Mexican border, where he developed his ideas on rural architecture and land conservation, which have influenced practitioners in this area. Judd's writings are, to this day, seen as the most comprehensive statement of Minimalist art; his work both defined a new lexicon of sculptural concerns and contributed to a revised notion of the process of beholding.

Influences and Connections

-

![Anish Kapoor]() Anish Kapoor

Anish Kapoor -

![Julian Opie]() Julian Opie

Julian Opie -

![Richard Tuttle]() Richard Tuttle

Richard Tuttle ![David Batchelor]() David Batchelor

David Batchelor![Joel Shapiro]() Joel Shapiro

Joel Shapiro

-

![Robert Morris]() Robert Morris

Robert Morris ![Thomas Lawson]() Thomas Lawson

Thomas Lawson

Useful Resources on Donald Judd

- Donald JuddOur PickBy David Raskin

- Donald Judd: ArchitectureBy Peter Noever, Brigitte Huck, Donald Judd, and Rudi Fuchs

- Donald Judd: ColoristBy Dietmar Elger, Donald Judd, Martin Engler, and William Agee

- Donald Judd: The Early Works 1955-1968By Donald Judd and Thomas Kellein

- Donald Judd: Architecture in Marfa, TexasBy Urs Peter Fluckiger and Ute Spengler

- Donald JuddBy David Batchelor, John Jervis, David Raskin, Nicholas Serota, Richard Shiff, and Donald Judd

- Donald Judd: Large Scale WorksBy Rudi Fuchs

- Donald Judd: Late WorkBy Donald Judd and Richard Shiff

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI