Summary of Installation Art

Installation art is a term generally used to describe artwork located in three-dimensional interior space as the word "install" means putting something inside of something else. It is often site-specific - designed to have a particular relationship, whether temporary or permanent, with its spatial environment on an architectural, conceptual, or social level. It also creates a high level of intimacy between itself and the viewer as it exists not as a precious object to be merely looked at but as a presence within the overall context of its container whether that is a building, museum, or designated room. Artworks are meant to evoke a mood or a feeling, and as such ask for a commitment from the viewer. The movement remains separate from its similar forms such as Land art, Intervention art, and Public art yet there are often overlaps between them. The ideas behind a piece of Installation art, and the responses it elicits, tend to be more important than the quality of its medium or technical merit. Artists champion this genre for its potential to transform the art world by surprising audiences and engaging viewers in new ways.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Installation art champions a shift in focus from what art visually represents to what it communicates. Installation artists are less focused on presenting an aesthetically pleasing object to viewers as they are enfolding that viewer into an environment or set of systems of their own creation. Tweaking the subjective perception of the viewer is the artist's desired outcome. Pieces belonging to this movement resonate with our own human experiences - like us they exist within, and are always in conversation with, their lived environments.

- Installation artists are preoccupied with making art a less isolated concept - by installing work beyond the galleries and museums and by using more utilitarian components such as found objects, industrial and everyday items, commonplace materials, and technologies of the populous. This movement has broadened the scope of what qualifies as artwork.

- Because Installation art is especially difficult to collect and sell, this movement pushes against the commodification of art, thereby defying the traditional mechanisms used to determine the value of artworks.

- Attempts to sell installations have raised questions about the process of dismantling and reinstalling work that was conceived for a particular location, and how that might or might not decrease the original meaning and value. It has also provoked dialogue within the art and archival communities about whether or not a temporary piece might be reconstructed and sold in the guise of its original, or whether a non-permanent piece may be recreated ad infinitum to perpetuate its existence.

Overview of Installation Art

"I was totally interested in the physical world and would always be making something," Rachel Whiteread said of her childhood, "Playing around with bits and pieces, changing them from one thing into another," became the early inspiration for her installation work.

Artworks and Artists of Installation Art

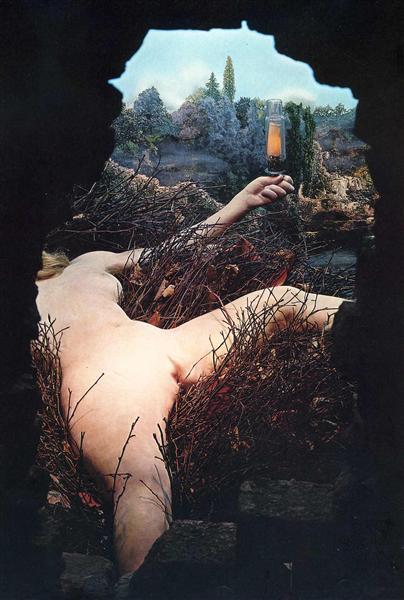

Étant donnés

Étant donnés was one of the first works to set up a specific and controlled viewing environment for audiences, which today remains a central tenet to Installation art. Duchamp surprised the art world with this three-dimensional tableau, since most believed he had decidedly retreated from art-making almost a quarter century before this, his final piece, was revealed.

The piece was described by the artist Jasper Johns as "the strangest work of art in any museum." At the time, it was. Imagine peering through two peepholes in a wooden door to find a reclining cast of a nude woman in the forefront of a lusciously painted landscape. By crafting an experience of voyeurism, rather than simply showing a traditional nude painting on the wall, Duchamp forced the viewer into a sense of complicity. Only one person at a time could peek in, making this a very enveloping experience and creating an intimate encounter with the work's enigmatic inhabitant.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art

The Dinner Party

The Dinner Party, an installation artwork that has become an icon of Feminist art, consists of a large triangular table adorned as a ceremonial banquet, with 39 place settings, each honoring an important woman. Each setting comprises embroidered runners, gold eating utensils, and porcelain plates that unapologetically resemble the female vulva and that vary in motif based on each specific honoree. The list of honorees includes, among others Sacajawea, Virginia Woolf, and the goddess Kali. The names of another 999 women are inscribed in gold on the white floor beneath the banquet table.

By creating this emulation of an event that audience members could easily relate to -the honorary dinner - and by designing the piece in a triangular fashion that would promote many people walking around and reviewing the place settings simultaneously, the artist sparked dialogue about these women who had been under-documented in history. Viewing the piece became an event in itself. By delivering her message through a three-dimensional, physical piece rather than a written manifesto or painted tableau, she proved the power in the presence signature to Installation art.

Wall Drawing #260, On Black Walls, All Two-Part Combinations of White Arcs from Corners and Sides, and White Straight, Not-Straight, and Broken Lines

Sol LeWitt's Wall Drawing #260 is one among hundreds of wall drawings started in 1969, which the artist continued to produce throughout his prolific career. Not only would LeWitt create a drawing for one specific location, he would then maintain detailed instructions on its composition so that others could duplicate it in other spaces going forward, even after his death. Even if LeWitt's Wall Drawings are ephemeral and endlessly replicated, the idea behind their initial conception lives on undiluted.

This seminal line of work inaugurated a new relationship between drawing and architectural spaces, furthering Installation art's site-specificity. By claiming entire walls, LeWitt's drawings responded to the spaces they occupied and enclosed viewers in work that alternated between soothing symmetry and dazzling randomness.

These drawings were also radical inclusions into the Installation art canon because they challenged the preciousness and permanence that is expected from fine art. They are birthed in conceptualism and carried out with simple tools. They are not confined to the originating artists' hand and they can be duplicated in multiple settings ad infinitum.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii

Nam June Paik's 1974 report to the Art Program of the Rockefeller Foundation forecasted the emergence of what he called a "broadband communication network," an electronic information "superhighway" - quite amazingly, this would become true by the 1990s with the rise of Internet connectivity. This interest in nascent technologies led Paik to create many enormous, free standing structures out of TV screens, cable, DVD players, and more. Multimedia experiences of this sort are a common theme in Installation art, allowing the artist to command the viewer's attention in a blunt, sensory-based way (Paik's creations are some of the first and innovative in this genre).

For this piece, the artist arranged over 300 TV screens into the shape of a map of the United States and outlined each state with bright neon lights, with each screen playing video clips reminiscent of the state it represents. Forty feet long and fifteen feet high, the work is a monumental record of the physical and cultural contours of America. Aside from delineating each state firmly, the neon outlines also represented the web of interstate highways that were increasingly unifying the country both economically and culturally. Encountering this massive installation was an overwhelming experience - the amalgam of voices, light, and information became a noisy testament of how the advent of media completely transformed American lives.

Smithsonian American Art Museum

My Bed

My Bed, by Tracey Emin, has inspired as much vitriol as it has critical acclaim throughout the years. The installation was a literal autobiographical presentation; the result of four bed-ridden, depressed days during which Emin accumulated debris surrounding her bed such as used condoms, blood stained underwear, and empty bottles. The piece, which the artist produced after a traumatic relationship breakdown, has been labeled self-absorbed and delusional by some, and seminal and inspired by others.

The one thing critics and enthusiasts alike can agree on is that My Bed forever changed the course of Installation art with its blatant realism. By taking her actual bed and displaying it as art Emin furthered the development of the movement's concern with bringing a more intimate experience to the viewer. The visually narrative portrait of Emin's life at the time and its candid nature created an engulfing atmosphere that eloquently evoked genuine experience. Audience members might either shudder in revulsion over the scene of personal debauchery or shirk guiltily inward with the knowledge that we all harbor our own dirty laundry. This piece also distanced itself resolutely from representational art as it reveled in its own mundanity and refused to stand in for any loftier concerns.

The Duerckheim Collection

Work No. 227: The lights going on and off

Martin Creed's Work No. 227: The lights going on and off consisted of an empty room which was lit up for five seconds, and then darkened for the following five seconds in a recurring pattern. This subtle intervention with the room's illumination, an intervention we all stage in our own homes regularly, might compel viewers to reconsider taken-for-granted elements of their everyday lives.

By playing solely with light in this minimalist piece, the artist sought to jostle viewer expectations. Creed wanted people to interact with the space as if it were a non-static entity and to gain new perspectives of something familiar - a key tool of Installation art. He did so by toying with their preconceived expectations of a seemingly dormant place. When encountering its animation, audiences were forced to interact more attentively with the room's physicality. Through subtle and mundane interventions Creed, like many other installation artists, was able to engage viewers in new ways.

Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Obliteration Room

Yayoi Kusama's Obliteration Room started out as a simple room, a completely commonplace one barring the fact that it was entirely painted over in white. Curious audience members were given a sheet of colored stickers made in accordance with the artist's specifications, and then invited to place the stickers anywhere they liked in the blank canvas of the room. Over the course of time the surfaces were transformed into an explosion of color with thousands of conglomerated spots covering every available surface.

Kusama was careful to choose a domestic environment that audiences would find familiar so that participants, especially children, would feel comfortable engaging with the work freely. The piece was her way of engaging with the surface of an architectural space and of handing over some of the creative process to the audience, thus involving them fully in the development of this spotted interior. This dynamic piece took Installation art's history of active viewer participation one step further by allowing them to actually co-create the work. It also allowed them to become fully immersed in an experience that significantly affected the senses but was also true to the artist's singular voice. Kusama is famously known for suffering life-long mental illness and polka dot-infused hallucinations, so in a way, this piece invited viewers to share a vivid glimpse into her own barraged mind.

Queensland Art Gallery

The Matter of Time

Richard Serra's primary focus is on large-scale site-specific sculptures made from industrial materials that exist in conversation with the physical spaces they occupy. According to him, "I consider space to be a material. The articulation of space has come to take precedence over other concerns. I attempt to use sculptural form to make space distinct." Viewing these sculptures necessitates moving around and through them, and thus encountering them from constantly shifting perspectives.

The Matter of Time is an installation comprising one of Serra's older sculptures, entitled Snake, in addition to 8 new, torqued pieces of steel. It occupies an entire gallery space in the Guggenheim Bilbao Museo. The different shapes made of weathered metal vary from simple elliptical ones to more complex spiral forms, and as viewers walk among these forms they move through varying passages of steel. The spaces between the sheets of curved metal change from being narrow and encroaching to being wide and open causing the viewer to experience constant disorientation. Serra's choice of material, with its textured rust and spectrum of browns and oranges, adds yet another layer of visual interest to this breathtaking installation.

Guggenheim Bilbao Museo

Shibboleth

Doris Salcedo's Shibboleth, a winding crack in the floor that ran the length of The Tate's Turbine Hall, managed to be both unobtrusive and intensely engaging. The Colombian artist created a fissure of varying width in the museum's floor and placed in it a concrete cast of rock with a wire fence set inside. The crevice measures 548 feet in length, and the depth varies from being a thin opening to a more cavernous one. Salcedo's fissure is meant to represent the immigrant experience in Europe. The title of the piece, "Shibboleth," refers to a word, phrase, or custom that may be used to determine if someone truly belongs to a particular group or place. In a manner characteristic of Installation art, this site-specific piece engages the viewers by demanding that they come up close to the crack and then shift their distance as they encounter its variations, handing them an experience that brings to mind notions of boundaries, discomfort, and safety.

materials - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Rain Room

In Rain Room, the collaborative studio group Random International, created a fully immersive environment, which travelled to various museums and architectural spaces consisting of an entire room filled with rain. Barely lit from above, visitors stood on the periphery to take in the emulation of a natural phenomenon. As guests stepped into the rain, their body heat triggered the rain to stop only in the spaces that contained them. It was meant to give a person peaceful respite from everyday life and to provoke sensory reflection on the relationship between man and nature. It also provided viewers the opportunity to control the rain. The piece aimed to question the human experience within a machine-led world.

Rain Room represents the exciting contemporary cross section of creativity, science, and technology currently informing cutting-edge installations that expand our traditional ideas of art.

Beginnings of Installation Art

Early Influences

Installation art did not arise from a particular collective impetus, or an organized intention. Rather, it arose organically from a lineage of conceptual, theatrical, site, and time specific ventures by various artists from within multiple movements. Installation art's roots are often traced back to the great Conceptual artists like Marcel Duchamp, the first to place a mundane toilet seat into the "fine art" setting in all of its literal plainness, to be considered in an out-of-context setting. Duchamp's readymades thus became precursors to this genre alongside other early influencers like the avant-garde Dadaists, who were the first Conceptual artists who chose to focus on making works that generated questions rather than crafting aesthetically pleasing objects. German artist Kurt Schwitters with his anti-commerce Merz objects-from-everyday-life collages and El Lissitzky with his Proun paintings that were a radical re-conception of space and material expressed early Installation art concerns along with notes of Spatialism - a movement that championed a synthesis of sound, sight, space, motion, and time into new forms of art. All of these prior efforts alongside inspiration from the theater - specifically seen in Performance art legends such as the Gutai group from Japan, who staged large-scale multimedia environments, coalesced into the birth of Installation art.

The earlier version of this innovative category of art was found in the expressionistic "environments," of artists in the 1950s and '60s such as Allan Kaprow. Kaprow curated entire gallery spaces into objects of art in which the guest might be absorbed. In his significant piece Words (1961), he installed rolls of paper with jumbled phrases and played audio recordings for the audience as they moved through the installation. Yves Klein was another pioneer of the curated environment, although his approach was a much sparser one. The Void, a piece made by Klein in 1958, featured a white gallery room, which was radically empty. It sought to validate space as an object worthy of artistic attention, thus shaping a path for Installation art.

Naming the Style: The 1970s

The term "Installation art" came of use in the 1970s to describe works attentive to the entirety of the spaces they occupied and to the audience's viewing process. During these decades of social, political, and cultural upheaval, the art world entered a time of experimentation that blurred the boundaries between disciplines. Installation artists were increasingly interested in doing work that could be displayed unconventionally and that would take into account the viewer's entire sensory experience. Bruce Nauman's claustrophobic works during the 1970s, for example, played with the audience's discomfort and aimed to make viewers feel out of sync with their surroundings. As visitors walked through his staged corridors and rooms, they experienced feelings of being locked-in or abandoned. For artists such as Vito Acconci, honing in on the audience's discomfort was also a means of engagement. In a 1972 performance entitled Seedbed, the artist masturbated under an installed, temporary floor at the Sonnabend Gallery while visitors walked overhead and heard him voicing sexual scenarios that involved them.

Shifting Concerns

Initially, art critics focused solely on the site-specific and ephemeral nature of Installation artwork to define it, but this focus shifted as proponents of the genre began to make work referencing cultural contexts and social concerns. Debates around art's relationship to people's everyday socio-economic reality spurred the transformation of Installation Art, during the late 70s.

The increase in venues for contemporary art and the vogue of large-scale exhibitions in the 1980s paved the way for Installation Art's current pervasiveness. Cildo Meireles's Through (1983-1989), for example, was a highly politicized piece that invited viewers to move thorough a labyrinth of barriers, shattered glass, and other disconcerting obstructions. The piece was meant to be a critique of social repression, consumerism, and political censorship. Bill Viola was another artist who carefully curated environments. He was noted for his use of video technology to explore elemental human experiences. For the Installation Room for St. John of the Cross (1983), for example, Viola created a black cubicle with a viewing window through which audiences could see a small color monitor perched atop a wooden table and alongside a metal pitcher. A screen in the background showed an image of a snow-covered mountain while a voice quietly recited poetry, making this a soothing and fully immersive scene.

By the 1990s, an even more involved viewer participation had surfaced as a central issue for Installation artists. Carsten Holler and Rosemarie Trockel, for example, created House for Pigs and People (1997) - a metaphor for social division that consisted of a house partitioned into two by one-way mirrored glass. People occupied one side of the house while pigs occupied the other, and the mirror enabled the people to see the pigs, but not the other way around. The artists felt that by immersing the viewers literally into the concept they were trying to express, viewers would have a visceral rather than an intellectual experience.

From the 2000s on Installation art has seen an increase in the incorporation of ever-burgeoning technological advances into works that create even more immersive environments. These highly stimulating works employ light, sensors, computers, and video realities and can be web-based, gallery-based, and even mobile-based installations. Bruce Nauman continues to work with audio recordings to create controlled situations in works such as Raw Materials (2004). The piece brings together multiple, overlapping readings of text which range in content from the stark repetition of single words to the more gasping recitation of longer texts in a sound installation. Some artists design these installation pieces so that they respond to interventions from audience members, such as in Maurice Benayoun's Brain Factory (2016). The piece translates visitor's emotions into visual data through a 3D printer so that audience and machine work together to produce the artwork. Brainwaves detected in the viewer are treated as abstract fodder to inform the materialization of solid objects and sculptures.

Installation Art: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Site Specificity: Location as The Integral Element

This category of art emerged during the 1960s as artists, disillusioned with the increasing commodification of the art world, began to break with artistic conventions in search of alternatives. Many Installation artists began making work that was solely created to exist in interrelationship with a particular space. Thus, if it were to be removed from said space, it would lose its meaning.

A great example of this is Walter De Maria's New York Earth Room (1977), on long-term display at the Dia Art Foundation. The piece consists of an entire room filled with dirt - De Maria's attempt to bring nature inside, to in fact contain what is regularly viewed as free from containment. Andy Goldsworthy has done similar experiments in manipulating nature. He's been known to paint entire walls of galleries and other architectural spaces with mud. As the mud dries and cracks, the pieces physically change and deteriorate allowing viewers to witness erosion in real time. German artist Eberhard Bosslet uses existing spaces to inspire construction projects. Since 1985, he has created many interior works using industrial building materials that exist as structural bodies that merge seamlessly within existing architectural frameworks. Kara Walker is known for affixing her black silhouettes depicting the African American experience directly onto walls, so that her messages of the ever-pervasiveness of racism cannot be removed or erased.

Conceptualism

Installation art also overlaps with the Conceptual art movement, since they both prioritize the importance of ideas over the work's technical merit. However, Conceptual art tends to be more understated and minimalist, whereas Installation art is often bold and more object-based. Some examples that connect the two movements include Jenny Holzer's works since the 1970s where she has expressed her own ideas about the human condition via text-based light projections and LED sculptural signage across the walls of many public buildings. Her thoughts become one with the surroundings, inviting visitors directly into her mind. When British artist Damien Hirst wanted to express society's global dependency on pharmaceuticals, he built actual pharmacy cabinets stocked with medicine bottles. The shelves from top to bottom corresponded with the human body - drugs for the head filled the top shelf and so on down to the bottom shelf for ailments of the feet. In 2010, when visitors to Ai Weiwei's Sunflower Seeds, 2010 at the Tate were allowed to take away one of (nearly) a billion tiny porcelain seeds piled on the floor of an entire gallery space, they also took away reflections on the geo-politics of cultural and economic exchange surrounding the words "Made in China."

Interaction and Immersion: Emphasis On Viewer Engagement

Pieces belonging to this category of Installation art shift the focus from art as a mere object to art as an instigator of dialogue. By occupying spaces so intentionally the artwork forces viewers into close interactions, so that viewing Installation art is more akin to an act of engagement than to one of contemplation. Artist Olafur Eliasson, has said, "I always try to make work that activates the viewer to be a co-producer of our shared reality." Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang epitomizes this notion. After strategically placing gunpowder on giant surfaces or constructions, he then stages public explosions of the works that rival exciting firecracker shows. After the sparks die down, gorgeous, soot-dark paintings are left to contemplate. Another artist, Rachel Whiteread, is known for large-scale installations that provoke the audience to consider interior space. In Embankment, she filled a room at the Tate museum with hundreds of white cubes cast from the insides of empty boxes and containers. As guests walked through and around these positive impressions of negative space, they were compelled to reflect upon all the "ghosts" of internal spaces in their own lives.

Some Installation artists create fully immersive environments in order to encapsulate the viewer within an experience completely separate from reality. These pieces become like amusement park attractions or experiential activities for the visitor's willing participation. A prime illustration is Yayoi Kusama's Infinity Room (2016), an installation inside an entire room of the Broad Museum, to which ticket-holding visitors enter one at a time to experience alone. The black room lit with thousands of tiny lights provokes feelings of being in space, or somewhere out of this world.

With the advent of technological advances, artists in this genre increasingly seek to captivate the viewer's every sense through smell, sound, performance, and immersive video reality (all connected to the loosely used term 4-D.) Artist Nathaniel Stern's works are often in direct collaboration with viewers as they require the movements of visitors' body parts to influence various actions by the artwork. In one piece, enter: hektor (2001), he had guests chase projected words with their arms to trigger spoken words.

Capitalizing on Massive Scale

Grand projects that transform public places into spaces for contemplation have long belonged to the realm of Installation art, with large-scale commissions having become requisite pieces in most major art museums. These works make bold statements and tend to be crowd favorites, but some argue that large-scale pieces have become overly ubiquitous and gimmicky, with public appeal far outstripping the pieces' artistic merit. Indeed, well known artists often seem to turn to the manufacturing of these massive Installations sure to catch the public's fancy, and to further catapult their fame. Duo Christo and Jean-Claude, largely known for spectacular outdoor works, once filled the fifty foot by fifty foot atrium of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia with a two floors high mastaba consisting of 1,240 oil barrels that guests could barely walk around in traversing the space. Some of Anish Kapoor's most famous work befit this category, in particular his enormous sculptural interventions into buildings that (often invasively) overtake multiple areas, rooms, and even floors.

Perception of Space

Some installation art endeavors to tweak our perception of space by manipulating an environment. For example, renowned artist James Turrell works with architecture, light, and shadow to eliminate a person's depth perception. In his seminal work Breathing Light (2013) for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, he transformed a room through strategically placed LEDs into an all-encompassing experience that enclosed the viewer in what felt like a breathing, heavenly womb. In The Weather Project (2003), Olafur Eliasson brought the outside inside by transforming a room, through the use of monofrequency lights and haze, into an eerie expression of the sun. Richard Serra is known for massive metal sculptural forms that warp, undulate, and command interior spaces in ways that tweak a viewer's equilibrium and sense of balance as they walk into, throughout, and around the gargantuan-scale works. These types of installations transport audiences into seemingly other dimensions, oftentimes provoking thoughts about existence - the physical, ethereal, and/or spiritual.

Later Developments - After Installation Art

Contemporary artists continue to use Installation art as a vehicle to inform a complete, unified experience. With the advent of revolutionary technologies and a rapidly expanding digital art toolbox, it can be said that artists are only just beginning to understand the possibilities of Installation art 2.0. Recently, installation artists have been turning toward work that immerses viewers in a virtual reality such as Daniel Steegmann Mangrane's Phantom (2015). The piece transports viewers to a Brazilian rain forest, complete with rustling leaves and imposing tree trunks. Although these new technologies haven't yet been widely adopted by the art world, many believe they are primed to emerge as one of the foremost directions in contemporary art's future.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI