Summary of Readymade and The Found Object

Post-World War I culture was suffering a deep malaise with many artists disenfranchised with a society that could participate in such atrocities - and so, artists sought to break out of traditional or historical modes of creating art, they searched for new ways to innovate by delving into every aspect of their culture and compelling new thought. From within this surge of rebellious re-investigation rose the "readymade," a genre in which artists chose ordinary found objects from everyday life, and repositioned them as works of art so that their original significance disappeared in light of sparking new points of view. This jostled society's attitude towards what art was supposed to, or could potentially be, and injected a spontaneous, fresh context into a staid lexicon. It also paved the way for Conceptual Art, which became more about presenting ideas and the process of exploring them rather than focusing on a finished work of art.

Today, the readymade in art is a common motif, as regular an addition to artists' work as paint and other more traditional mediums. In contemporary society, artists continue their on-going investigation of regular objects, elevating them to art status as means of investigating society's relationship with the environment, consumerism, mass production, and our attachment to the physical world of our own manifestation.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The primary principles of the Dada readymade philosophy were to 1.) choose an object, a creative act in itself; 2.) cancel that object's familiar purpose by presenting it not in its usual functionary role but as a work of "art"; and 3.) add a title to it that potentially provoked a new thought or meaning.

- Although readymades were undisguised presentations of usual objects as themselves, they were often manipulated, modified, or combined into assemblages to compel further disambiguity, further disassociating them from any preconceived meaning.

- Under the readymade light, an artist became a "chooser" rather than "maker." This laid the groundwork for art as something that could exist to express concepts, process, and ideas rather than being confined to only the visual presentation.

- The readymade became a way to challenge societal norms in that it broke down expectations, questioned originality, revealed familiar associations as meaningless mental constructs, and explored the commodification of beauty in general. Aesthetic, taste, and mass production were all put under a microscope, often with an attitude of irreverence or even humor.

- Man's relationship with objects in general was taken into question through the readymade. What everyday objects do we take for granted? What new associations might be generated when said objects are removed from a position of complacency into one of fresh perspective? How might this disrupt regular thinking and trigger the unconscious?

The Important Artists and Works of Readymade and The Found Object

Bicycle Wheel

This work, described by Duchamp as a "pleasant gadget," combined a stool with a wheel, which was intermittently turned so that it would revolve for viewers. Duchamp termed this an "assisted readymade" as it was based on the combination of two different objects.

The arrangement of these two objects is visually striking, even comical. As Duchamp experienced himself, there is also something very pleasing in how tactical this work appears, as if it invites the viewer to spin the wheel themselves. The work fuses together two different useful objects, but in doing so, renders them both stripped of their original function. We can no longer ride the bike or sit on the stool so the objects are totally reimagined. Instead, they become objects for us to contemplate, to look at, to treat as we would anything else in a gallery space. By juxtaposing two different objects, Duchamp creates a new thing, which is neither one nor the other.

Wooden stool, metal bicycle wheel - Israel Museum, Jerusalem

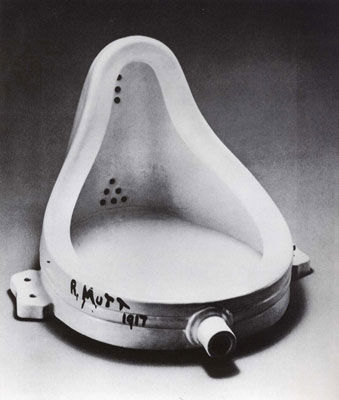

The Fountain

The Fountain is one of the best-known works of the 20th century and continues to be considered the most influential piece of modern art. Though its composition is simple - a porcelain urinal lay on its side and inscribed with the words "R. Mutt" and date - its impact on the art world cannot be understated.

With this piece, Duchamp could be saying any number of things, but most importantly, he seems to decimate the cultural reverence there is for art objects by making one of the most ubiquitous and lowly objects into one of admiration. By unifying the sacred and the profane, Duchamp rethinks the innate demands of art by asking us to laugh or feel puzzled by the object, rather than respecting it. Duchamp shows that even an ordinary toilet can become worth an incredible amount of money simply because an artist has selected it.

Duchamp also makes a joke about the good aesthetic "taste" of the artist by picking an object that most people would simply mock. He seems to challenge his audience, asking them: could you display this in your home? Clearly, one might never think it is in good taste to display a toilet, but by abstracting it from its use, Duchamp asks his audience to recontextualize the work, so it is no longer defined by its use, but instead by its lack of purpose. If we do this, then the object no longer becomes distasteful, but merely another object. By using indifference in selecting his objects, and transforming them into something other, Duchamp wanted to avoid making art into a purely aesthetic ideal that appealed only to the eye.

Though Duchamp is famous for his creation of the readymade, he actually only created thirteen such works of his own. Aside from The Fountain, this included Bicycle Wheel and Bottle Rack (1914), Prelude to a Broken Arm (1915), Pulled at 4 Pins (1915), Comb (1915), Traveller's Folding Item (1916), Trap (1917), 50cc of Paris Air (1919), Fresh Window (1920), Brawl at Austerlitz (1921), Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette (1921), and Why Not Sneeze, Rose Selavy (1921).

Porcelain urinal. Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz - Multiple versions

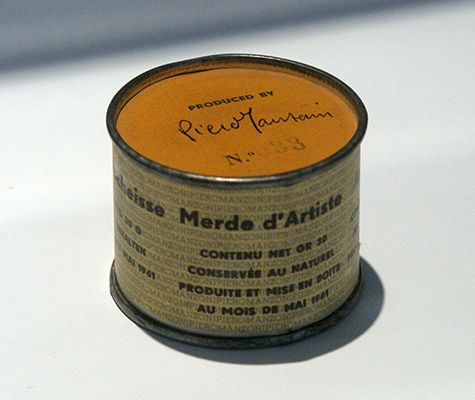

God

This work was created in collaboration by The Baroness and painter and photographer Morton Schamberg. The piece was originally solely attributed to Schamberg, but recent scholarship has found that it is likely to have been a combined effort. The piece is a section of cast-iron plumbing that has been turned upside down and mounted to a wooden base.

God is considered the sister piece to Duchamp's The Fountain in both the use of banal plumbing parts and its re-contextualized orientation. Because The Baroness and Duchamp were dear friends, even living for a time in the same apartment building, and because God was made in the same year as The Fountain, there has been much speculation about which piece was actually created first. Like The Fountain, God takes an overlooked item and repositions it in a new setting, questioning the inherent value in any piece of art. However, Freytag-Loringhoven places a different emphasis on this piece through its title. By naming this phallic-shaped piece God, she appears to make fun of the traditional idea of God as an authoritative figure. In joining together the high and the low, she questions the arbitrary boundary between the two, and the societal structures that keep them in place.

This piece also asks interesting questions about authorship, particularly in the fact that it has been misattributed in the past. By a woman artist naming a lowly object God, she gives herself a new power to name and to create, a power that is affiliated with God himself (notice God is traditionally considered male). Freytag-Loringhoven's playful and yet powerful work seeks to question the possibility of women to assert their own independence by challenging dominating power structures.

Cast iron plumbing trap - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Gift

Though Man Ray is best known for his photography, he tried his hand at many other forms of artwork throughout his career. In The Gift, Ray took an iron and added fourteen thumbtacks to its underside. The object was made on the day of his first solo exhibition in Paris with the help of musician and composer Erik Satie. They bought the two items from which this piece is made up, quickly put it together, and displayed it that evening.

The iron is visually striking in its new form. In its new combination, much like with Duchamp's Bicycle Wheel, a new object manifests, demanding another kind of attention. The domestic object becomes violent, even murderous, perhaps revealing the shadow sides of domestic spaces and familial homes. For example, if used to iron, rather smoothing the surface, this modified iron would cause harm and destruction. Curator Arturo Schwarz commented of this piece, "Man Ray never destroys, he always modifies and enriches. In this case, he provides the flatiron with a new role, a role that we dimly guess, and that probably accounts for the object's strange fascination." We might imagine then that this new iron is in fact waiting to discover its purpose, as we the viewers help surmise what that may be.

Iron with thumbtacks - Now Lost

Bull's Head

Upon first glance, this piece appears as a bull's head mounted to the wall - a universally familiar symbol of a hunter's trophy from a kill. But upon closer inspection its true identity, that of a simple bicycle seat and handles, emerges clear.

Picasso noted that for the sculpture to truly work, the viewer had to be able to see the bicycle parts and the bull's head at the same time. This meant that the work existed as a duality. Perhaps Picasso sought to show the malleability of shape and design in our day-to-day lives, revealing to viewers, like a magic trick, the way that we might "re-see" objects around us. Moreover, the piece also reminds us of our proximity to nature and animals: by finding an animal within a human object, he disrupts the boundary between our apparent sophistication as humans and reminds us of our previous reliance on beasts.

Picasso had explored the possibility of found objects in his earlier collages, but this work is more in line with the techniques of readymade. When the work was displayed in 1944 at a Salon in Paris, visitors were shocked by the sheer audacity of such a simple object placed into the context of high art and the piece was removed.

Picasso did not make many other readymades, though he sometimes added found objects into his assemblage sculptures. His Glass of Absinthe from 1914, for example, incorporated a real silver absinthe spoon balanced on the top of his bronze abstracted glass. His Head from 1958 is fashioned from a wooden box with buttons for eyes, creating an oddly charming human face from this simple combination. It seems that rather than the pure Readymade, Picasso was more interested in tricking the eye, taking advantage of the audience's constant search for sense and meaning in the world around them.

Bicycle seat - Picasso Museum, Paris

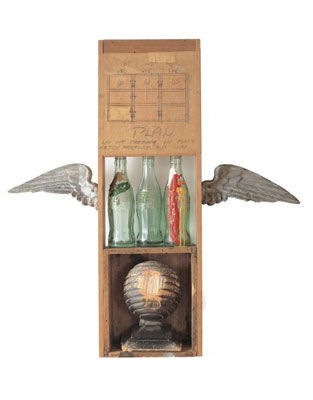

Coca-Cola Plan

In this piece, American artist Rauschenberg puts together various objects including glass, bottles, a wood newel cap, and iron wings into an eye-catching column. Rauschenberg also incorporates the ubiquitous Coca-Cola bottle, referencing our societal familiarity with the infiltration of branded objects. The wings on either side of the piece suggest its elevation beyond simple objects and the earthly realm. This is furthered by the wood newel cap, which looks almost like a globe mounted on a plinth, so that bottles rise far above the human world. Rauschenberg seems to be commenting not only on the "worship" of brands, but also on the creation of artworks in general, perhaps poking fun at our lofty ideals.

Rauschenberg made several similar works, what he coined "combines," throughout his career, including earlier pieces such as Charlene and Collection, both from 1954, which include a range of different materials and textures fixed to board or canvas, in evocative displays of the detritus of human life. The materials for these combines were often collected trash from the streets of New York City, suggesting the contingency and chance implicit within art making.

Rauschenberg experimented across media during his career, working in collage, photography, and performance as well as painting. He is considered a Neo-Dadaist (and part of the informal group that includes Jasper Johns, John Cage, and Edward Kienholtz) because of the influence Duchamp had on his work, not only through his use and innovation of readymade artworks, but because of his desire to interrogate the relationship between artist, viewer, and the production of meaning.

Pencil on paper, oil on three Coca-Cola bottles, wood newel cap, and cast metal wings on wood structure - The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

Sled

This piece is a sled on to which German artist Joseph Beuys attached a flashlight, a ball of lard, and a blanket of felt. Beuys said that the Tartars used such a sled when they rescued him in 1943. Beuys, who was a rear-gunner for a time in the Second World War, claimed that this "survival kit" kept him alive after he crashed on the Crimean front.

Though this story may well be apocryphal, the kit still seems to exude a sense of hope and comfort; the combination of the blanket and flashlight seem to suggest the possibility of a pathway somewhere safer or better, and that this is only a transitory state.

Like the earlier readymades, Beuys selected normal everyday objects and elevated them in the gallery setting. However, through the addition of his inspirational story, he makes this collection of objects theatrical, as if setting the scene for the beginning of a play. In this way Beuys asks questions about what story objects can tell, and how each of us gives objects purposes that go beyond their original function.

As a Conceptual artist, Beuys used the readymade as part of his wider artistic practice. As critic Valery Oisteanu comments "For Beuys, the readymade became part of a larger effort to reinvest artistic activity with metaphorical, ritual, political, and even spiritual significance". He saw the readymade as a means through which he could reimagine the role of the artist entirely, attempting to reject the commodification of all artworks, and break down the barrier between art and real life.

Beuys worked in many different forms, including sculpture, performance art, installation art, and theory throughout his career. His work was in deep conversation with politics and he sought to question the constructions and ideas of society.

Wooden sled, flashlight, cloth straps, cord, wax - Harvard Art Museum, Boston

New Hoover Convertibles, Green, Red, Brown, New Shelton Wet/Dry 10 Gallon Displaced Doubledecker

American artist Jeff Koons produces provocative and challenging work that looks to the relationship between high and low culture. His work is often comprised of banal, everyday objects that he places in new contexts to elevate them to the status of an art object. Like Duchamp before him, he sought to show the arbitrary line between objects of varying value, and perhaps exposing the underlining cynicism of the art world.

This early piece is made from four different Hoover vacuums sealed in a Perspex case. Each brand-name vacuum is lit with a fluorescent light as if presented in a showroom for purchase. This is furthered by the word "convertibles" as the title reminds audiences of America's very particular obsession with car culture, transporting spectators from the gallery space to the car showroom floor. Koons himself commented that '"if one of my works was to be turned on, it would be destroyed", echoing the ideas of Duchamp. In abstracting these objects from their normal contexts, they are no longer useful objects; this means that this piece only exists as an artwork because it has rendered these objects completely useless. Here Koons thinks about the idea of value within commodities and demonstrates that there is no such thing as innate value; instead our relationships with objects are totally contingent and changeable.

Under Koons' spotlight, we are shown that the value we place onto objects lives in a wildly transient zone, directed by our personal relationship and association with things we normally take for granted when viewed only in their familiar contexts.

4 vacuum cleaners, Perspex and fluorescent lights - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

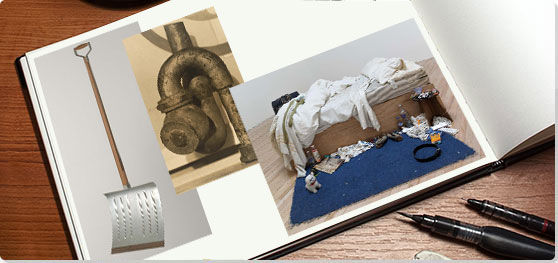

My Bed

British artist Tracey Emin works across media, producing works that explore her own life and history from many different angles. This piece competed for the Turner prize in 1999. It replicated a difficult moment in Emin's life when she was drinking heavily; she stayed in bed for several days, not eating and suffering deeply after a break-up. The scene is filled with bottles, dirty clothes, condoms, and a pregnancy test.

The work caused a stir at the time, with many think pieces produced about whether or not this qualified as an artwork. By using her own life's objects to illustrate the many different emotions centered on personal space and intimacy, Emin was often pegged as "confessional," opening her up to judgment and scrutiny by her viewers. A woman famously turned up at the gallery wanting to tidy the mess of the installation up.

Art critic Skye Sherwin wrote that this piece is "a theatrical arrangement worthy of Jacobean tragedy: a violent mess of sex and death" and the work does indeed engage with the mess of desire and of the body. In bringing this wide variety of objects into the gallery space, Emin seeks to tug at a viewer's sense of propriety about what one can and cannot share.

Under Emin's guise, the objects in our lives become fodder for artwork, helping to stage narratives and lend context to an artist's message.

Box frame, mattress, linens, pillows and various objects - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Tate Thames Dig

American artist Mark Dion's work seeks to explore the way that the world around is arranged and organized. He often produces works from found objects, using many different combinations of discarded or no longer used materials. This piece is representative of that work, but here it is also tied strongly to place. It was produced with the help of a team of volunteers who scoured the banks of the River Thames in London to look for discarded objects. Dion then categorized and labelled the objects he found, noting trends and similarities between what was found at this location.

Though the objects are damaged or perhaps seem unimportant, Dion begins to construct an alternative history of London through his collection. By showcasing discarded items, he suggests another way of understanding our present moment that is not built from what we want to see, but from what we throw away or overlook. As art writers Tina Fiske and Giorgia Bottinelli comment: "Each is a material witness, performing the same function as a historical proof". In this way, Dion asks the audience to think about the production of culture and what it is we choose to see or ignore about our lives. By showcasing these objects in a cabinet, he asks viewers to contemplate his collection as one of value, that is based on time and experience rather than any other kind of value system - or indeed money.

Through Dion’s lens, the readymade becomes an object of sociological import, evidence of time and place, providing a clear capsule into life at any given moment.

Wooden cabinet, porcelain, earthenware, metal, animal bones, glass and 2 maps - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Beginnings

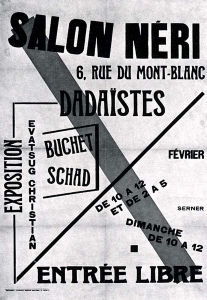

Dada

After the horrors of the First World War, many artists, writers, and intellectuals started to question every aspect of their culture that had allowed it to occur. Artists started to think about how technology, consumerism, art, and politics were all interrelated. Romanian-French poet Tristan Tzara noted, "The beginnings of Dada were not the beginnings of art, but of disgust." Artists and writers such as Tzara, Hugo Ball, Man Ray, Hannah Höch and Max Ernst decided that the only way to respond to these realizations was through irreverent and (potentially) nonsensical works. Dada artists used techniques such as collage, assemblage, and photomontage to form their works, creating new linguistic and visual languages that attempted to exist outside the rigid structures of contemporary society. The term Dada itself, though contested in origin, is said to come from its meaning of both 'Yes, yes' in Romanian and 'rocking horse' in French, demonstrating its transnational origins. The Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich Switzerland was an early hangout for Dada artists, but the movement soon spread to Paris and then to New York.

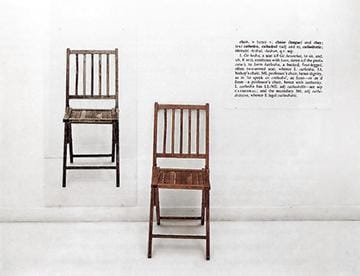

The Found Object

The phrase "found object" is a direct translation from the French "objets trouves," meaning everyday objects inserted into an art context thus transformed from non-art to art. Though found objects had been associated with the art world pre-1900s, they were mostly included as pieces of overall collections such as in Victorian taxonomy, or in cabinets of "curiosities." It wasn't until the beginning of the 20th century that artists started incorporating them into their work. Pablo Picasso is widely considered to have produced the first piece of art to incorporate found materials when, in 1912, he used the back of a chair as part of Still Life with Chair Caning. The piece was also considered one of the first collages of Synthetic Cubism. By incorporating this material into his work, Picasso began to break down the barrier distinctions between art and real life by demonstrating that art is always produced from real life.

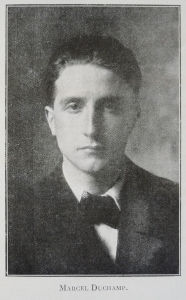

Marcel Duchamp

However, it was French-American artist Marcel Duchamp who took the found object to new heights in his theorizing of the readymade. Duchamp is understood to be the initiator of the readymade, though the term was already in use much earlier to denote objects made through manufacturing processes. He had been painting since 1904 and studied at the Academie Julien in Paris between 1904-5. His early works show the influence of Cubism and looked forward to the work of Futurists: his Nude Descending the Staircase (1912), for example, attempted to show the body in motion, suggesting the static and the active through fragmented lines.

However, that same year, Duchamp began to move away from painting, rejecting what he termed "retinal art." He started developing the idea of the readymade after he placed a bike wheel on a stool one day in his studio, and from there experimented with other forms including either objects he selected on their own or adapted or changed in some small way. For Duchamp, the readymade is in direct conversation with industry and manufacturing: by taking mass-made objects and elevating them by putting them in new contexts and defining them as art, he questions the very process through which something becomes art in the first place.

His most famous readymade came in 1917 when Duchamp submitted The Fountain, a plain porcelain urinal, to the Society of Independent Artists for their show of modern art under the pseudonym of "R. Mutt." Duchamp was part of the Board of the Society and the piece created much debate amongst its members about its status as art. An emergency meeting rendered it a reject and it was hidden from view in the show.

Duchamp was furious with this decision and in the following month, using a pseudonym, wrote a piece in The Blind Man, the magazine that he co-edited, in order to defend the work. He wrote: "Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view - and created a new thought for that object." In this statement, Jonathan Jones finds a new starting point for art in the 20th century, noting, "It's as if contemporary art history begins with him." Though he only made thirteen readymades, this groundbreaking work set up the foundation for the field of Conceptual Art by seeking to redefine the possibilities of art, in that art was not something merely to be enjoyed visually but that it could, instead, encompass ideas and process.

Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

Though Duchamp is often credited as the creator of the readymade concept, the German artist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven is now also thought of as an equal pioneer. Loringhoven traveled throughout Europe, moving in bohemian artist circles and working in various jobs as a waitress, a chorus girl, a performance artist, and later a model for photographers. But it was in America that she began to develop as an artist. In New York she met and married Baron Leo von Freytag-Loringhoven, leading to her nickname “The Baroness”. She made her first piece with a found object in 1913, a rusted metal ring, which she called Enduring Ornament. The Baroness went on to make other works, including her collaboration with Morton Livingston Schamberg entitled God, in the same year as Duchamp's Fountain. Via these powerful personalities the readymade became a way through which one could challenge society's norms and expectations, providing a means of exploring the commodification of aesthetics.

Readymade and Surrealism

Duchamp's work was extremely influential in both art theory and practice and influenced many of his contemporaries and friends. André Breton, one of the proponents of Surrealism, used and wrote about the found object and the readymade as ways to disrupt thinking and trigger the unconscious. In contrast to Duchamp, Breton explored society's identification of the object via an essay in 1937 entitled "The Crisis of the Object." He wanted to rethink the way that humans interacted with objects in general, and how through techniques like estrangement or assemblage, new associations could be generated. Salvador Dalí's Lobster Telephone aimed to reveal unconscious associations and desires through the juxtaposition of a telephone and a plaster cast lobster. As well as being immediately amusing and challenging, the combination appeared to reference the language of dreams, in which new combinations of objects and ideas become commonplace.

Concepts and Styles

Originality

While repurposing existing objects into new artistic contexts, one of the most vexing issues readymade artists face is the question of originality. What is an original piece of art? How much effort does an artist have to put into a work for us to say it is a unique work of art? Can an artist truly claim ownership of a work of art if it already existed outside of his or her co-option of the object? These are just some of the questions readymades provoke. They also engage with questions about our relationships with familiar objects on a daily basis. By placing them in an art context we are sometimes led to see how much we take for granted that which is in front of our eyes every day.

For some critics, the idea of the readymades in and of themselves are controversial because sometimes the original works, which have been lost or damaged or worn by time, have been remade by the artists themselves or by galleries. Bicycle Wheel (1913), for example, Duchamp's first readymade, has been remade three times, while the originals of many others have been lost altogether. However, in their remaking, these pieces ask even more profound questions about originality: can we still say that this is the same work as originally displayed? What does it do to the value of art if we can simply remake a lost work?

Humor and Visual Puns

Humor and play were regular themes in readymades, and artists often included jokes or visual puns into their work. As with Dadaism, Duchamp's work sought to subvert cultural norms and play with sense and meaning. His work L.H.O.O.Q (1919) combines a visual and verbal pun: the title when read aloud in French reads "elle a chaud au cul" meaning "she has a hot ass" and the image reflects a moustache and goatee, pencil-drawn onto a reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa. The work is a playful take on one of the Renaissance's most revered works and articulates a new artistic intention to excavate new meanings from old objects, be they everyday articles or works of great import. Humor is central in this approach, as it seeks to find new ways to think about expression and art-making.

Aesthetics and Taste

Readymades also play with the idea of aesthetic taste and choice. We traditionally view art in the context of a gallery as a purchasable item to be bought and displayed. Readymades challenge the idea of art as decorative by incorporating or using objects that are not identified as beautiful in any immediate sense. In doing this, the readymade implies that a work of art is not merely an aesthetic object. Duchamp suggested that in order to create a readymade one had to have an "indifferent taste," in which one could put aside their normal criteria for beauty and try to engage with the object in a radically new way. By divorcing art from personal or subjective taste, Duchamp paved the way for Conceptual Art, in which ideas took precedence over the final aesthetic of the piece.

Mass Production

In seeking to select mass-produced objects, Duchamp and other artists considered the relationship between art and technology and industry. The 20th century saw a radical shift in the way that objects were made through increased mechanization and the roll out of factories across the world. Mass production encourages the population to consider objects in terms of their function as opposed to beauty. Yet via readymades, artists could encourage their viewers to rethink these objects and consider them for their aesthetic beauty rather than their pre-defined purpose.

Later Developments

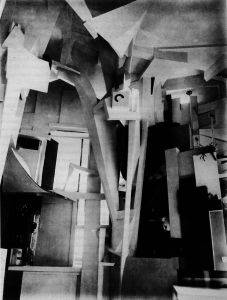

The Readymade and Neo-Dada

The readymade was used often in the late 20th century by artists whose work engaged with postmodernism, aiming to critique mass cultural production. Many young artists in America embraced the theories and ideas espoused by Duchamp. Robert Rauschenberg in particular was very influenced by Dadaism and tended to use found objects in his collages as a means of dissolving the boundary between high and low culture. His First Landing Jump (1961), riffed on Duchamp's Bicycle Wheel with its inclusion of a tire, while also speaking to the car-obsessed culture of 1960s America. He, along with others, became known as Neo-Dadaists through their adoption of humor, play, and critique of popular culture and aesthetic taste.

Other Neo-Dadaists such as Joseph Beuys and Jasper Johns responded to the ideas of Duchamp through their creations of work that disrupted or challenged the relationship between art object and gallery space. Johns' sculptures Lightbulb and Flashlight (both 1958) hearken back to Duchamp's disruptive aims, while also looking backwards to artistic craft and process. Johns bought both objects, and then sculpted them into a base using metal. The works became composite readymade sculptures, further problematizing the idea of creation, taste, and originality.

Readymades would lay important ground for Conceptual Art in that they allowed artists to consider and refine the presentation of an idea in itself as a work of art. They would also go on to influence contemporary artists, most dramatically seen both in the Pop Art that emerged in the 1960s, which appropriated everyday images from popular culture and elevated them into the annals of visual art, and the Neo Geo movement which turned its spotlight on everyday objects of mass production and consumerism.

Young British Artists

In the late 80s and early 90s, the readymade took new form through a group of artists who became known as the Young British Artists (YBAs). These artists, such as Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, and Rachel Whiteread, were infamous for shocking work that sold for very high prices. They also often looked toward mass-produced items from popular culture, or ubiquitous objects from everyday life, and experimented with placing them in new contexts. They were inspired by Duchamp's idea of "selection" and "taste," in which an object only becomes art through the artist's coining it art. The most famous readymade from this era is probably Tracey Emin's My Bed, which was shortlisted for the 1999 Turner Prize. Emin received much criticism because people thought the work (her actual bed and the mess around it) was lazy and did not show any artistic skill. In response to claims that anyone could make this work, Emin responded, "Well, they didn't, did they? No one had ever done that before."

Useful Resources on Readymade and The Found Object

- Remaking the Readymade: Duchamp, Man Ray, and the Conundrum of the ReplicaBy Adina Kamien-Kazhdan

- Pictorial Normalism: On Marcel Duchamp's Passage from Painting to the ReadymadeBy Thierry de Duve, trans. by Dana Polan

- Marcel Duchamps' Fountain: One Hundred Years LaterOur PickBy Robert Kilroy

- Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the CenturyBy R Kuenzli

- Self PortraitOur PickBy Man Ray

- Mark DionOur PickBy John Berger and Norman Bryson