Summary of Raoul Hausmann

One of the founders of Berlin Dada, Hausmann is credited with formulating the technique of photomontage. With his companion Hannah Höch, he devised a cut-and-paste "anti-art" strategy that was nothing short of an afront to the aesthetic and ideological standards that had come to define earlier and current avant-garde movements. In Berlin Dada's attempts to build a new aesthetic code for a shell-shocked post-war German society, his output extended to assemblage, experiments in sound poetry, and polemical writings. After the demise of the Group, Hausmann effectively reinvented himself in the duel role of fine art photographer and painter, and as the would-be inventor of an ambitious sound/image conversion machine he named the "Optophone".

Accomplishments

- There is a split of opinion over who "invented" photomontage. George Grosz and John Heartfield lay claim to that accolade though it was soon countered by Hausmann and Höch. What is generally agreed upon, however, is that Hausmann and Höch were considered the more expressive - or the Dada anti-art "aesthetes" - whereas Grosz and Heartfield were associated with a more direct approach that allied more candidly with the political aims of the Group.

- Hausmann also gained renown as a pioneer of the phonetic poem; a form of poetry that abandoned rational words and sentences in favor of typed letters and punctuation marks that formed on the page an impression or a picture rather than a poem (or prose) to be read. His poems had a life beyond the page and were designed to be recited in the rhythmic manner of an avant-garde musical piece. Hausmann's fascination in the fusion of sounds and images saw him patent his blueprint for an Optophone machine (sadly never realized in the artist's lifetime).

- Hausmann believed that "the embryo of God exists in all men". What he called the "new European man" would emerge from the ruins of a world war in the same way the post-revolutionary Russian worker had built a new Soviet society. His anti-art aesthetic would play a not-insignificant part in destroying what he called the "soulless force of the materialistic and militaristic machine" that he believed had given rise to a septic German society.

- Prior to his starring role in the within the Dada group, Hausmann was whetting his anti-establishment appetite through his involvement with the Die Brücke movement and specifically his training under one of its greatest protagonists, Erich Heckel. It was at Heckel's atelier, indeed, that Hausmann produced a series of "primitive" lithographs and woodcuts that were his first protests against the Academic art establishment and the bourgeois political systems which he was so intent on dismantling.

The Life of Raoul Hausmann

Speaking of his relationship with Höch, Hausmann stated "We called [the] process 'photomontage,' because it embodied our refusal to play the part of the artist". Berlin Dada would, he claimed, "strive anew towards conformity with the mechanical work process" and the new German society "will have to get used to the idea of seeing art originating in the factories".

Important Art by Raoul Hausmann

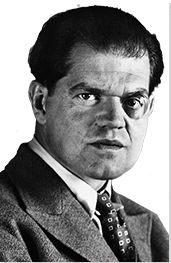

Portrait of Hannah Höch

Having already taken inspiration from the bold outlines of Matisse's figures in a series of early watercolors, Hausmann's first encounter with German Expressionism came on a visit to Herwarth Walden's Sturm Gallery in 1912 and subsequently through his involvement with Erich Heckel with whom he became close friends. Indeed, he remained committed to expressionism as late as 1917, the same year he co-formed the Berlin Dada Club. Having joined Heckel's atelier, Hausmann produced a series of lithographs and woodcuts and, firmly in keeping with the ideology of the Die Brücke movement's political opposition to the bourgeois refinements of academic painting, Hausmann favored the more "primitive" modes of artistic expression. He also took on the role of staff writer for Walden's magazine, also called Der Strum, which gave him a platform for his polemical "anti-art" essays.

Hausmann met Hannah Höch in 1915; the pair quickly embarking on an artistic and tempestuous sexual relationship that would run more-or-less the course of the Berlin Dada movement. His portrait of Höch, who appears to be reclined in (their shared) bed, carries the same expressive energy and aggressive bold outlines that were a feature of the work of Heckel, and fellow Die Brücke group member, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. In keeping with his Expressionist colleagues, Hausmann initially welcomed the war, naively buying into the group's belief that it would help cleanse German society of its staid bourgeois ideology and instigate the birth of the "new man". He did not hold his pro-war beliefs for long, however, and, anticipating the birth of Berlin Dada, would soon publish two essays on the relationship between artistic production and human subjectivity in Franz Pfemfert's anti-militaristic Die Aktion journal.

Oil on canvas

bbbb

Hausmann's phonetic poetry was designed to be "read" and performed. Featuring letters and punctuation marks in an arrangement that forms a picture rather than a poem (or prose), his formations, that do not create words or sentences, but which still might be spoken or uttered, resemble rather small insects crawling in different directions, and in different formations, across the white page. The letters are not arbitrarily placed, however, and there is a vague meandering shape that leads our eyes ultimately down to the horizontal line of letters at the bottom of the page "o n o o o h h o o u u u m h n". The interplay between text and sound opens up the opportunity for a synesthetic experience if one sees in them an innate rhythm. The phonetic poem also prompts the more meditative viewer/reader to consider the nature of semantics and the arbitrary relationship between words and their meaning (or lack of).

This was one of Hausmann's first phonetic poems. Having been constructed on a typewriter, it was very much created to be performed like a musical piece, while the visual appearance of the letters themselves turned text into image. As historian Jeanne Willette writes "The vertical-horizontal arrangement [of text on page] was invaded and dis-arranged. Rather than organization, the Dada artists stirred up disorganization, which became their contrarian design plan". The writer and Curator Timothy O. Benson adds that Hausmann's phonetic poems "were proposing a new language combining perception and articulation in the subconscious; a form of processing and expressing the world that was no longer limited to just one sense. As one of the first in his experimentation with phonetics, the aspect of performance came to be thoroughly formative for a lot of ideas later on in his life that toyed with the fusion of sound and image". Indeed, one could site bbbb as an antecedent of mid-twentieth-century Concrete Art movement in the way it offered a precise compositional structure at the expense of any kind of commitment to represent lived (or mythological) worlds.

Typewriter ink on paper

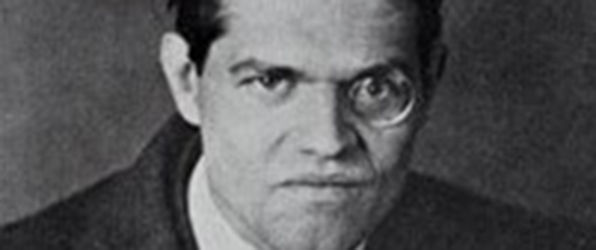

The Spirit of Our Time

With this sculpture Hausmann brought together a collection of seemingly random manufactured objects and in so doing he was in keeping with the Dadaist agenda of subverting aesthetic and artistic conventions and expectations. Indeed, The Spirit of Our Time is a classic work of Dada assemblage; giving everyday objects a new context and thereby prompting the viewer to rethink their perception of them. Hausmann said of the piece: "The everyday man has nothing but the capacities which chance has glued to his skull, on the exterior, the brain was vacant. So I took a nice wooden head, polished it for a long time with sandpaper. 1crowned it with a collapsible cup. I fixed a wallet to the back of it. 1 took a small jewel box and attached it in place of the right ear. 1 added further a typographic cylinder inside and a pipe stem. Now on to the left side. And yes, 1had a mind to change materials. 1 fixed onto a wooden ruler a piece of bronze used to raise an old antiquated camera and I looked at it. [I] still needed this little white cardboard with the number 22 because, obviously, the spirit of our time has but a numerical signification. Thus it still stands today with its screws in the temples and a piece of a centimeter ruler on the forehead".

Coming in the immediate aftermath of World War One, this piece remains probably Hausmann's most iconic work. It represents the absurdity of "the war to end all wars" and the idea that human world has been overrun by machines, and that the "machines of war" have reduced the loss of so much human life to an empty list of statistics. The title of the work could be read thus as a direct reference to the influential German philosopher Georg Willhelm Friedrich Hegel, who discussed the concept of "spirit" "geist" (or "zeitgeist"), as that which encompassed the human spirit at a given time and place. In any case, Historian Timothy O. Benson suggested that Hausmann's take on the idea of "geist" was ironic and manifest in "the concrete materiality of the objects used in place of raw art materials". Hausmann himself seemed to confirm Benson's reading when stating, "Dada is the full absence of what is called Geist (Spirit). Why have Geist in a world that runs on mechanically?"

Hairdresser's wig-making dummy with mixed media - Pompidou Centre, Paris

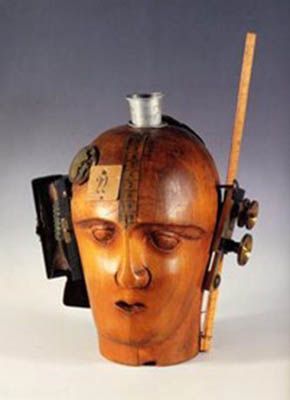

The Art Critic

The background to this photomontage is taken from a poem/bill-poster that Hausmann displayed on the streets of Berlin. The central figure, with his tongue sticking out, often presumed (given his distinctive attire and the fact he is holding a pencil) to be Grosz (or an amalgamation of Grosz and Heartfield) is comprised of a series of cut out and drawn images.

The female and male onlookers - separated by Hausmann's calling card - appear to be cut respectively from a print advertisement or catalogue and from newspaper print (possibly modeled from a photograph of Hausmann), while the triangular cut of a German banknote is perhaps an indictment of the "art industry" in which the critic - the arbiter of taste - is such a key figure. Indeed, the art critic's outsized pencil is brandished sword-like as a weapon. As Willette writes, "Cutting and pasting from anonymous sources and turning the media against itself suited the purposes of the Dada artists in Berlin and the result was a critique of the status quo of society and the new Weimar government. The photomontage was a deconstruction and a form of destruction, wiping away the last remnants of the dead hand of history in search of a new mode of marking on the walls of the present".

Benson writes, "Hausmann used photography as an integral element to present the "art reporter" in a sparse atmosphere of fashion (shoes and spats), Dada art (the poster-poem which forms its foundation), the newspaper, and the "currency" of the banknote and postage stamp. Absent are the references to high art often included in the Klebebilder [glued picture] of the Grosz-Heartfield "Konzern" ["group"] which would suggest the traditional values of art criticism".

The Dadaist's attitude to art criticism was firmly expressed by the author Wieland Herzfeld who wrote in his introduction to the famous Dada Fair exhibition catalogue of 1920: "If it [producing art] does happen, at least there should be no despotic standpoint laid down, and the broad masses should not have their pleasure in creative activity spoiled by the arrogance of experts from some supercilious guild".

Lithograph and printed paper on paper

The Optophone

This work was Hausmann's great scientific project. It was a proposal for a machine that could turn sound into images and vice-versa. It was for Hausmann a machine that the modern age deserved; a device that expanded the sensory experiences; a synaesthestic experience of mixing the senses. It was in fact an expansion of the ideas being explored by Wassily Kandinsky who explored the concept of synaesthesia by translating sound into abstract paintings. Hausmann looked in fact to the natural world and the example of bees whose "optophonetic" makeup consisted of six hundred tube eyes which allow for the simultaneous perception of sound and vision in a single organ. The Optophone never made it past the stage of prototype even though Hausmann received a patent for his invention in 1934.

In 1926, The Hungarian polymath Lazlo Moholy-Nagy showed Hausmann a letter he had received from Albert Einstein in which the physicist suggested that Hausmann's blueprint for the Optophone was a triumph in scientific conception. Einstein's words of encouragement were enough to push Hausmann to develop the plans into something more fully formed but his ambitions were thwarted by the onset of a second world war and the lack of an investor. In a letter dated June 23, 1963, to the French avant-garde poet and musician, Henri Chopin, Hausmann wrote: "I would like to attract your attention to the fact that since 1922 I have been developing the theory of the optophone, an apparatus that transforms visible forms into sound, and vice versa. I had an English patent - 'Procedure for combining numbers on the photoelectric base' - which was a variant on this apparatus, and at the same time the first robot. The only thing that kept me from constructing an optophone was money".

In 2018 avant-garde musicians Geneviève Strosser and Florent Jodelet presented the latest of several attempts over the years (an undertaking made easier, of course, with modern computer technology) to realize Hausmann's project through an optophone concert. Staged at Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris, it featured a light show that combined images and sounds generated by the rhythm of Hausmann's poetry.

Reproduction of the original drawing accompanying the patent

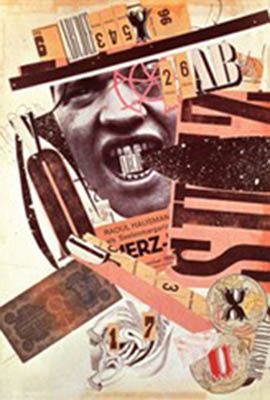

ABCD

Benson wrote that "What the Dadaists referred to as the Klebebild [glued picture] and the Plastik [sculpture] were to them the logical place to begin the formation of a new language and myth" and that, like "the numerous other avant-garde groups, the Dadaists worked communally, creating their own 'testing ground' in which their art works were developed". Hausmann's last photomontage stands as both an ode to the spirit of communal experimentation and also a Dadaist self-portrait.

This photomontage, with one image overlapping and partially obscuring another, suggests that the cutout elements have been almost shaken into place. The mixture of text and numbers, and in particular the repetition of the alphabet at two points in the picture, is typical of the Dadaist's interest in written language as an aesthetic device. It is also in keeping with Hausmann's own phonetic forms and sound poems. We see too a mixture of circular and linear elements that lead our eyes in a zig zag fashion across the picture plane. This adds to the chaotic bustle and "noise" of the work which is a metaphor for the idea of a society in chaos. The face is Hausmann's and the letters he grips in his teeth act as a sort of speech bubble which is confirmed with the ticket or flyer for one of his phonetic poem recitals placed just under his chin. There is a gynecological diagram (at the bottom center of the image) which, as well as creating an element of controversy, relates to the idea of creation, and perhaps even the creation of art. The tickets to the Kaiser jubilee in his hat, meanwhile, hints at banalities of a culture he and his Dadaist colleague's had fought so hard to reverse.

Indian ink and magazine illustrations cut and pasted on paper

The Drunken Sailor

From around 1927, while still living in Germany, Hausmann became a dedicated photographer, using his camera to make nudes and record land and seascapes during visits to the Baltic coast. Onced forced into exile in Ibiza (with the rise of Nazism), his photography focused on the local life and Ibizan architecture before he was forced once more to emigrate in 1936 (this time due to Spanish fascism). It was an intensive ten year period that saw Hausmann develop an individual photographic style that accommodated documentary and lyrical elements. But it was a career path that was likely foisted upon him given that it was the only artistic activity in which he could safely indulge without the threat of political persecution. From Ibiza he moved to Zurich and then Prague in 1937 before arriving in France in 1938, spending the years of occupation in Peyrat-le-Château before reaching Limoges where he settled for good. Here he lived a life of virtual isolation but kept alive active correspondences with old and new colleagues including Jasper Johns, Wolf Vostell and Daniel Spoerri.

This photomontage differs from his earlier Dada pieces inasmuch as it is composed of original (rather than found) photographic images. It depicts a sort of palimpsest face, and although the different camera angles provide us with multiple perspectives, the sailor's facial expression appears to be unchanged. It is almost impossible to separate out the images but their combination evokes a sense of pictorial movement which corresponds with the title of the work. Indeed, Hausmann has created a dizzying effect that leaves the viewer with a sense of intoxication themselves. The model is unknown, but the French auction house, Ader, described how on the reverse of the image the words "jamais deux sans trois" ("never two without three"), which is the French way of saying "third time lucky". We are able to guess from this that Hausmann printed three exposures and was perhaps inspired by the silver print photography of Man Ray, himself an early advocate of Dada.

Gelatin silver print

Biography of Raoul Hausmann

Childhood and Education

Hausmann was born to middle-class Viennese parents, Gabriele and Viktor Hausmann, during the height of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Viktor, a professional Academy painter and restorer, was unmoved by the rise of the Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) and Vienna Secession groups that were blossoming in Vienna at that time and, in 1901, relocated his family to Berlin where he continued to paint empirical studies and work on restoration projects.

In 1905, Hausmann met the violinist Elfride Schaeffer whom he married in 1907 following the birth of their daughter, Vera, a year earlier. Viktor tutored his son until he entered formal scholastic training (at the relatively late aged of 22) at Arthur Lewin-Funcke's Atelier for Painting and Sculpture, one of a number of private art studios in Berlin. Attending between 1908-11, he focused mostly on nude and anatomy drawing. He also experimented with typographical designs and assisted his father on a restoration project at Hamburg's City Hall in 1914. It was around this time that Hausmann made the acquaintance of the unconventional utopian architect Johannes Baader, a lifelong friend and future Dadaist collaborator. Hausmann later described Baader as "the man who was necessary for Dada because there was nothing which could stop him once he got an idea into his head".

Early Work

Prior to the war, Germany had been alive with creative experimentation. The Die Brücke movement, which thrived in Dresden between 1905-13, and Der Blaue Reiter movement which brought together the great German expressionist painters in Munich between 1911-14, put Germany firmly on the map of European modernism. But once the First World War had started (in 1914), German art entered a phase of cultural isolation and stagnation. However, being Austrian born, Hausmann avoided the draft and was thus relatively free to pursue his artistic interests as he saw fit. He remained largely faithful to the expressionistic style associated with the Die Brucke group and also showed a keen interested in the work of Alexander Archipenko (an artist much admired - as much as they were allowed to "worship" individual artists - by the Berlin Dadaists) which was neither realistic nor idealistic. Hausmann had in fact cherished an early copy of Guillaume Apollinaire's foreword to Archipenko's solo exhibition at the Sturm Galleries in late 1913 in which Apollinaire stated that "Archipenko seeks above all the purity of forms. He wants to find the most abstract, most symbolic, newest forms, and he wants to be able to shape them as he pleases".

On leaving Lewin-Funcke's atelier, Hausmann fell under the influence of the painters Ludwig Meidner and Erich Heckel, the latter introducing him to the techniques of woodcutting and lithography. As the art historian Timothy O. Benson observed, Hausmann was "particularly close to the work of Heckel. A close friend, Hausmann was sketching and pulling prints in Heckel's studio during 1915". Unlike Heckel, however, "whose attitude at this time has aptly been characterized as tragic", Hausmann had "been interested simply in experimenting with the formal elements of the Expressionists' vocabulary". By now Hausmann had also started to compliment his painting experiments with a burgeoning career as a writer, publishing articles scolding the German arts establishment in Der Strum and Franz Pfemfert's left-wing, antimilitarist journal Die Aktion.

Mature Period

In 1915 Hausmann met Hannah Höch who was studying graphic arts at Berlin's Royal Museum of Applied Arts. The pair, who became lovers, forged a combustible personal and artistic partnership that lasted into the early 1920s. Also in 1916, Hausmann met the anarchist Otto Gross and the radical writer Franz Jung. The two men introduced Hausmann, respectively, to the writings of Sigmund Freud, and Walt Whitman and Friedrich Nietzsche. Hausmann began to see himself in the role of the "new man" which would feed into the Berlin Dada philosophy.

Höch had produced two "mini sculptures" - or "puppets" - in 1916 that are generally thought to have been modelled on the geometric costume Hugo Ball wore for his famous sound poem ("Karawane") recital at Zurich's Cabaret Voltaire earlier that year. But Hausmann's (and Höch's) formal introduction to the Dada movement came through Richard Hülsenbeck whom Hausmann first met in 1917. Benson wrote, "When Hülsenbeck arrived in Berlin from Zurich sometime in January 1917, he had brought with him the 'magic' word 'Dada' as well as a comprehensive set of tactics and assumptions for launching a movement - what [Hans] Richter has called the Dada bomb which had been perfected and tested in Zurich".

Benson surmised that it was the Russian Revolution of 1917 that inspired Hülsenbeck "to dress the word Dada in a decidedly political and internationalist tone in his 'Dadarede' [Dada speech] delivered at a Vortragsabend ["lecture night"] in I. B. Neumann's gallery in Berlin on January 22, 1918". His speech won over the movement's politically minded figures including Heartfield, Grosz, Herzfelde, and Jung. But Hausmann and Baader came to Dada by a non-political route and "were very much closer to Huelsenbeck's image of man as a container of pandemonium as he had expressed it in his essay, 'Der neue Mensch'".

Baader, the self-proclaimed "Oberdada" ("Upper Dada"), and Hausmann, the "Dadasoph" ("philosophical Dada"), embarked on a series of Dadaist turns together. In 1917, for instance, the pair founded Christus GmbH, its goal being to support conscientious objectors by likening them to Christian martyrs. A year later Baader staged a performance in the Berlin cathedral called "Christus ist euch Wurst" ("Christ you're a sausage") which provoked a public outcry and saw him arrested for blasphemy. An outraged Hausmann dispatched an angry letter to Berlin's Minister of Culture defending his friend's actions as an act of free speech.

In 1918, Hausmann and Höch took a vacation at the Baltic sea resort of Ostsee where, Höch later claimed, the pair had "invented" photomontage. In what was (is) a somewhat circular argument amongst Dadaists, George Grosz had claimed that it was he and John Heartfield who had invented photomontage in 1916 (in point of fact photomontage already had a commercial history dating back to the mid-1850s). In any case, Hausmann and Höch adapted the idea, not from examples made by Heartfield or Grosz, but rather by studying official group photographers of Prussian army regiments onto which had been pasted individual photographic portraits. These images were part of an enterprise by which paying customers, by having their images superimposed on the figures of smartly uniformed soldiers, could create a seamless fantasy of living a heroic military life. Hausmann and Höch saw the creative potential for photomontage to dismantle the myth that surrounded the modern art establishment. As the art historian Jeanne Willette wrote: "Taking up the scissors or a razor blade and cutting carefully around a complex printed photograph was a mechanical act, requiring dexterity but denying the individual touch of the artist's hand and eliminating the aesthetic pleasures of painting with pigment and rebuking the senses that revelled in pleasure derived from traditional 'art'". As Hausmann himself put it, "We called [the] process 'photomontage,' because it embodied our refusal to play the part of the artist. We regarded ourselves as engineers, and our work as construction: we assembled our work, like a fitter".

Hausmann, Baader and Hülsenbeck (who was, with Hugo Ball, Jean Arp, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco and Emmy Hennings, co-founder of the Cabaret Voltaire which opened in Zürich in 1915) formed the "Berlin Dada Club" which was active between 1918-23. Complementing to their journal Der Dada, they wrote a Dadaist manifesto in which they demanded that Dada denounce aestheticism and, in a second anti-art manifesto entitled "The New Material in Painting", Hausmann proposed that Dada should produce alternatives to oil painting (which was dismissed as a bourgeois activity). He also published a piece called "Synthetisches Cino der Malerei" ("Synthetic Cinema of Painting") in which he declared: "In Dada you will recognize your real state of mind: miraculous constellations in real material, wire, glass, cardboard, tissue, corresponding organically to your own equally brittle bulging fragility".

Hülsenbeck presented the first Dada speech, on January 22, 1918, at the avant-garde Neumann gallery on Kurfürstendamm. The first Berlin Dada Club "evening" took place on April 12, 1918. It was staged at a meeting of the Berliner Sezession (a breakaway group of artists, including Lovis Corinth and Max Liebermann, who formed a modernist challenge to the "official" Academy art) and featured a mixture of Dadaist performance and poetry recitals. The gathering was attended by Höch, Grosz (who read "syncopations" and poetry), Else Hadwinger (who recited Marinetti's "BeschieBung" ("Bombard-Ment") and Tzara's "Retaite" ("Retreat") to the accompaniment of drum noises supplied by Hülsenbeck), Heartfield, Jung, Baader, Wieland Herzfelde and Walter Mehring. Hausmann brought the evening's proceedings to a close by shouting his "New Materials" manifesto at the now near-riotous audience. The newspaper, Berliner Börsen-Courier, reported the next day that "The threat of violence hung in the air. One envisioned Corinth's pictures torn to shreds with chair legs. But in the end it didn't come to that. As Raoul Hausmann shouted his programmatic plans for dadaist painting into the noise of the crowd, the manager of the sezession gallery turned the lights out on him".

In 1918 Hausmann produced the "poster poem", OFFEAHBDC, a collection of randomly selected letters meant to be recited, and the "optophonetic poem" OFFEAH, which was a visual poem created out of a collage of typography. Hausmann was by now working extensively in photomontage, producing one of his signature pieces, Art Critic, in 1919 and, arguably his most famous piece of all, an assemblage called, Mechanical Head: Spirit of Our Age, which featured a hairdresser's wig dummy adorned with an absurdist collection of items including a tape measure, a tin cup, a wooden ruler, and various mechanical parts. In early 1919 Hausmann and Baader announced the formation of the so-called Dadaist Republik Nikolassee and staged a "Propaganda Evening" at Berlin's Café Austria. But undoubtedly the most famous of the Dadaist events was The First International Dada Fair which opened on June 5th 1920.

The First International Dada Fair, which followed on the back of a short, and well attended, tour of East Germany and Czechoslovakia, saw the group subvert the rules for a traditional art exhibition by cramming the collected artworks into a small gallery space. Hausmann exhibited photomontages, Synthetisches Cino der Malerei (now thought to be lost), Self-Portrait of the Dadasoph and Tatlin Lives at Home (featuring the face of the Russian artist). The cover for the exhibition catalogue, meanwhile, featured Hausmann's motorcar photomontage and collage, Elasticum. Herzfelde, Heartfield's brother, and himself an author of some note, wrote "Zur Einführung" ("For The Introduction") of the exhibition catalogue which included the following passage: "Any creation is Dadaist that is produced uninfluenced by and heedless of, public authorities and values‚ provided the depiction is anti-illusionist and motivated entirely by the urge to keep on eroding the present world, which is obviously in a state of disintegration, of metamorphosis. The past is only important and relevant in so far as its cult must be fought [...] The Dadaists take credit for being the vanguard of dilettantism, for the art dilettante is nothing but the victim of a prejudiced, arrogant, and aristocratic conception of life".

In the fall of 1921, Hausmann, Höch and Kurt Schwitters took an "Anti-Dada" show to Prague where Hausmann recited sound poems and delivered a manifesto that announced his intention to make a machine ("Optophone") that would translate audio signals into visual signals and vice-a-versa. Hausmann published his "Dadasophy" (philosophy of Dada) in several publications (including Der Dada which lasted just three issues between 1918-20), and, in 1921, contributed written pieces to the Dutch De Stijl publication, but the Dada movement was evolving into Surrealism while his relationship with Höch had also run its course. Hausmann created his final photomontage, ABCD, a poster publicizing one of his poetry recitals which showed the artist clenching the letters (ABCD) in his teeth, in 1923. Hausmann was now poised to reinvent himself as a fine artist.

Late Period

Benson wrote that "For Hausmann, Dada had been a heuristic enterprise, a 'practical self - decontamination.' As Dada came to an end, he sought to transform the New Man from clown and puppet into engineer and constructor, the insider of the new Gemeinschaft [community] of functionality and practicality. Departing from satire, Hausmann attempted to probe deeper into perception and consciousness in a new activity which he proclaimed in 1921 as 'Presentism': a 'synthesis of spirit and matter' and 'the elevation of the so-called sciences and arts to the level of the present'".

In 1923 Hausmann married his second wife, the painter Hedwig Mankiewitz. This coincided with his shift towards more conventional artistic modes, namely photography. Known predominantly for his nudes, portraits and landscapes, he became a well-respected fine-art photographer and published several theoretical articles on photography throughout the 1920s. However, Hausmann's Dadaist legacy brought him to the attention of the Nazis who were persecuting "degenerate" artists. Hausmann, Mankiewitz, who was Jewish, and the couple's shared lover, Vera Broido (who was also Jewish) fled Germany for Ibiza in 1933. Once settled on the Spanish island, Hausmann developed a keen interest in ethnography, wrote about, and photographed, the island's architecture and published his work in the French-language journals Oeuvres and Revue anthropologique. Hausmann also pursued his interest in the relationship between the sound and typography and finally presented his blueprint for his "Optophone", device which he patented in England in 1934.

With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, and with Ibiza under military rule, Hausmann, who was a vocal supporter of Spanish anti-fascist groups, and Mankiewitz travelled to Zurich and Prague before arriving in France on the eve of the outbreak of World War Two. Despite receiving an invitation from Laszlo Moholy-Nagy to teach at the Institute of Design in Chicago (the so-called "New Bauhaus"), the Hausmann's had their application to emigrate to the United States refused. Instead, they moved to Peyrat-le-Château in central France where they hid out in a rooftop cabin. Hausmann taught language lessons in German, English and Spanish and the couple also met Marthe Prévot with whom they entered into another ménage à trois relationship.

After the Normandy landings in 1944 the trio settled for good in Limoges. As one of the many artists in exile, Hausmann corresponded with Maholy-Nagy who sent him a parcel of photographic paper which he used to produce photograms, and Kurt Schwitters, with whom he published a journal entitled Pin. Hausmann pursued his interest in photography throughout the late 1940s and 1950s. He exhibited regularly and wrote poetry and articles on photography for journals including A bis Z and Camera.

In later years, Hausmann also renewed his interest in oil painting. Benson noted in fact that "This return to traditional artistic media and the application of illusionist perspective was accompanied by a demand for 'materialism in painting'" that dated back in fact to 1920 when he published his manifesto "Die Gesetze der Malerei" ("The Laws of Painting") and "presented [as] a monist interpretation of the elements of art, apparently as an alternative to Dadaism". Hausmann stated, "Painting is the visualization of material space through the relations of bodies. The concepts of bodies were discovered through the rules of stereometry and perspective, which made possible for the first time a clear conception of vision and the optical milieu".

In 1958 he published a memoir, Courier Dada, which tallied with the rise of the Neo-Dada movement in America. Artists including Yves Klein, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Allan Kaprow and George Maciunas were all associated with the rise of Neo-Dadaism. Hausmann had been in correspondence with a number of American avant-gardists and, in 1962, delivered the following denouncement in a letter to Maciunas: "I think even the Americans should not use the term "neodadaism" because "neo" means nothing and 'ism' is old-fashioned. Why not simply 'Fluxus'? It seems to me much better, because it's new, and dada is historic. I was in correspondence with Tzara, Hülsenbeck and Hans Richter concerning this question, and they all declare neodadaism does not exist. So long".

Hausmann continued to experiment with photography and photograms, recorded sound poetry and making oil paintings, which he transformed into pictorial writing, up until his death in 1971. His last work, the book, Am Anfang war Dada (At the Beginning Was Dada), was published posthumously in 1972.

The Legacy of Raoul Hausmann

As a founder of the Berlin Dada Club, Hausmann was one of the great political and cultural radicals of the post-war years. As part of his artistic agenda to invent the "New Man" and to usher in a new German society it was Hausmann, with Hannah Höch (and notwithstanding the counter argument that it originated with Grosz and Heartfield), who pioneered what would become the defining legacy of Berlin Dada: the art of photomontage. Its impact on twentieth and twenty-first century modernism and post-modernism is hard to overestimate with the collage technique of cutting and juxtaposing (and blending) photographic images being adopted (and adapted) by the Constructivists, The Surrealists, The Bauhaus Schools, Neo-Dada, Fluxus, Pop Art, and by contemporary artists as diverse as Martha Rosler, Barbara Kruger, David Hockney, Jeff Wall and Lorna Simpson.

Hausmann was also the leading proponent of the Dada poem through which he showed a daring disregard for semantic rules. His exploration of the overlaps between the audio and the visual in his poems, was later picked up on by Isadore Isou and the avant-garde Lettrist International (LI) movement during the mid-1940s. he pursued his goal of inventing a device for translating sounds into images (and vice-versa) throughout his career, and although his Optophone device was never realized in his own lifetime, as recently as 2018 the avant-garde musicians Geneviève Strosser and Florent Jodelet have sought to bring his Optophone to fruition. The Raoul Hausmann Fund has taken on the main responsibility for his legacy and an impressive archive of his poems, essays, photographs, letters and notebooks are held at the Musée d'Art Contemporain de la Haute-Vienne at the Château de Rochechouart - a magnificent thirteenth-century French Castle.

Influences and Connections

-

![Hannah Höch]() Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch -

![Alexander Archipenko]() Alexander Archipenko

Alexander Archipenko -

![Wassily Kandinsky]() Wassily Kandinsky

Wassily Kandinsky -

![Man Ray]() Man Ray

Man Ray ![Richard Huelsenbeck]() Richard Huelsenbeck

Richard Huelsenbeck

-

![Erich Heckel]() Erich Heckel

Erich Heckel ![Johannes Baader]() Johannes Baader

Johannes Baader- Arthur Lewin-Funcke

- Ludwig Meidner

-

![Die Brücke]() Die Brücke

Die Brücke - Berlin Dada

-

![Hannah Höch]() Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch -

![Robert Rauschenberg]() Robert Rauschenberg

Robert Rauschenberg -

![Jasper Johns]() Jasper Johns

Jasper Johns - Isadore Isou

Useful Resources on Raoul Hausmann

- DadaismBy Dietmar Elger

- Raoul Hausmann and Berlin DadaBy Timothy O. Benson

- Raoul Hausmann: Photographs 1927-1936By Cecile Bargues, Nik Cohn, David Benassayag, David Barriet, Beatrice Dider and Raould Hausmann

- PhotomontageBy Dawn Ades

- Dada and Surrealism: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions)By David Hopkins