Summary of Assemblage

In the early 20th century, many artists increasingly began incorporating everyday objects into their paintings and sculptures, blurring the lines between art and life. Ranging across styles, avant-garde artists created three-dimensional, mixed-media assemblages that questioned the very definition of art as it had come to be known. Using mass-produced objects and junk, artists like Marcel Duchamp often made satirical and biting critiques of modern, commercial culture. In the 1950s, Jean Dubuffet coined the term Assemblage for this hybrid art form, and while other artists used terms like Combines or Accumulations, the trend took off in the second half of the 20th century.

Artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, Arman, and Martha Rosler pushed the boundaries of Assemblage into the realm of Installation and Performance, creating immersive environments and experiential events. More contemporary artists such as David Hammons and Tracy Emin engage Assemblage techniques to create works that confront viewers in challenging ways.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Assemblage art combines mundane objects in new and surprising ways, requiring the viewer to question their relation to the world of objects around them. Sometimes used as social critique or as an exploration of the fantastical and dream worlds, Assemblage art gives objects new meanings, makes creative connections between disparate elements, and elevates non-art materials into the realm of art.

- In combining readymade or found objects with varying degrees of modifications, Assemblage art challenges the medium specificity that formalist critics insisted structured the progress of modern art. Blurring the distinctions between painting, sculpture, and theater, Assemblage art is not just an optical experiences but engages multiple senses and often requires more physical interaction on the viewer's part.

- Because it usually incorporates manufactured items and non-art materials, much Assemblage art aims to question notions of authorship and originality that have been so important to traditional concepts of the artist. In choosing the objects instead of hand-crafting them, the Assemblage artist subverts the traditional notion of the artist as a creator. Additionally, because Assemblage art is often a characteristic of folk art traditions, who can be considered an "artist" has greatly expanded over the decades, incorporating untrained and self-taught artists outside of the mainstream.

The Important Artists and Works of Assemblage

Bicycle Wheel

While Picasso and Braque invented modern collage by incorporating real objects into their paintings, Marcel Duchamp's creation of a sculpture from only mundane objects was the spark that eventually led to Assemblage art. The first of its kind, the work consists of a bicycle wheel mounted on a four-legged stool. Both elements, immediately recognizable, are transformed into something new as their everyday functions are disrupted. Rather than meeting the ground, the bicycle wheel rotates freely and continuously through the air, its circular shape and radiating spokes creating a geometric contrast to the triangular stool, and with the seat of the stool occupied, it is no longer available for a sitter and instead becomes a makeshift pedestal. Duchamp wrote, "The Bicycle Wheel is my first Readymade, so much so that at first it wasn't even called a Readymade. It still had little to do with the idea of the Readymade. Rather it had more to do with the idea of chance." As he further defined his concept of the readymade, he called this work, an "assisted readymade," indicating the alteration or combination of various found objects, a technique that greatly informed the development of Assemblage as a distinctive genre.

The work is also considered a pioneering example of Kinetic Art, a trend that emphasized movement in the artwork, and is closely aligned with Assemblage. It was the bicycle wheel's potential for movement that attracted Duchamp, as he said, "To set the wheel turning was very soothing, very comforting, a sort of opening of avenues on other things than material life of every day." In many ways, the heart of Assemblage can be traced back to Duchamp's questioning of definitions of art, originality, and our relation - in ways both good and bad - to the modern, physical world.

Wooden stool, metal bicycle wheel - Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Mechanischer Kopf (Der Geist Unserer Zeit) (The Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Time))

Various items, including a wooden ruler, a tape measure, a watch mechanism, a tin cup, are attached to a wooden model of a head, once used for making wigs. The work, the only existing Assemblage by Hausmann, conveys Hausmann's caustic assessment of the state of his country: "The German wants only his order, his king, his Sunday sermon, and his easy chair...has no more capabilities than those which chance has glued on the outside of his skull; his brain remains empty." In addition to being a commentary on the state of the German people, the subtitle The Spirit of Our Time alludes to the influential German philosopher Friedrich Hegel, who thought everything was mind. But art critic Jonathan Jones notes, the "sculpture might be seen as an aggressively Marxist reversal of Hegel: this is a head whose 'thoughts' are materially determined by objects literally fixed to it... a head that is penetrated and governed by brute external forces."

A leader of Berlin Dada, Hausmann's innovative use of Assemblage creates a sculpture that, by presenting a kind of robotic dummy, challenges the expressivity of the face that one sees in more realistic sculpture. At the same time, the work speaks to the fragmentation of identity and life that the artist and others experienced in the aftermath of World War I.

While Hausmann was known for his innovative photomontage, Mechanical Head has become his most famous work and is an important touchstone for the contemporary discourse on the cyborg. As art historian Matthew Biro wrote, Hasumann established "the cyborg as a figure of modern human identity: the cyborg to represent the new hybrid human: a half-organic, half-mechanized figure that he believed was appearing with ever greater frequency."

Hairdresser's wigmaking dummy, crocodile wallet, ruler, pocket watch mechanism and case, bronze segment of old camera, typewriter cylinder, segment of measuring tape, collapsible cup, the number "22", nails, and bolt - Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

Merzbau (Merz Building)

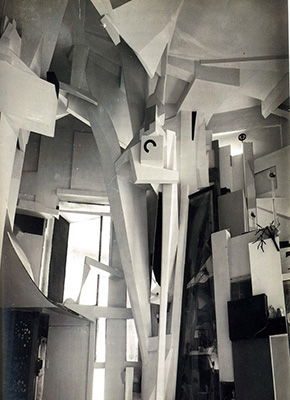

This photograph depicts a partial view of Schwitter's most ambitious project - his living space in Hanover, transformed by Assemblage into an installation. A vertical and angular column rises toward a cluster of planes and cubes on the ceiling, while on both sides of the image a profusion of forms both invite and reject a rational reading of the architectural space. Destroyed during the Second World War, only accounts and a few photographs testify to the original construction. Following her 1924 visit to the site, Dada artist and art historian Kate Steinitz described it as a "three-dimensional collage of wood, cardboard, iron scraps, broken furniture and picture frames."

Merzbau was a forerunner of what we today call installation, as Schwitters conceived of the space as an immersive environment where interactivity was a fundamental factor. As art historian Jaleh Mansoor wrote, Merzbau was "a continuous project altered daily, the small apertures were often sliced out of a larger mass, or covered over and buried under the agglomeration of objects, wood or plaster." Fellow Dada artists, including Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Hoch, Hans Richter, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, contributed pieces to the installation, which Schwitters originally called the Cathedral of Erotic Misery.

For Schwitters, the work was meant to be the all-consuming culmination of what he called Merz. In 1918, Schwitters began creating the over 2,000 abstract collages, paintings, and drawings that he called Merz. He connected its origins to the traumatic effects of World War I, explaining, "Things were in terrible turmoil... Everything had broken down and new things had to be made out of the fragments; and this is Merz." Including detritus, such as movie tickets, broken pipes, chicken wire, and metal scraps, he said Merz was "the combination of all conceivable materials for artistic purposes. And technically the principle of equal evaluation of the individual materials... A perambulator wheel, wire-netting, string and cotton wool are factors having equal rights with paint."

Forced to relocate several times during World War II, Schwitters created multiple Merzbaus, which were destroyed, and he left an unfinished one in England before his death. Based upon the surviving photographs, a reconstruction of the Merzbau was subsequently built in Hanover. Contemporary art critic Rachel Cook described visiting the site, "The walls have disappeared behind constructions which comprise a series of grottoes, columns, shelves and cubes.... The effect of all this strange geometry is disorienting and paradoxical. Even as you're beset by a sense that the floor is shrinking and the ceiling growing ever lower, the structure itself seems somehow to be infinite." Instead of creating a simple sculpture, Schwitters created a built environment, pushing Assemblage art beyond sculpture and into installation. Here was an art form that had to be physically experienced - walked through - in order to be comprehended.

Schwitters became foundational to later artists, including Robert Rauschenberg and Richard Hamilton who, as a student, helped move and restore part of the third Merzbau in England, and subsequent art movements, including Neo-Dada, Pop Art, and Arte Povera.

Paint, paper, cardboard, plaster, glass, mirror, metal, wood, electric lighting, and other materials - Destroyed in 1943

Object

This iconic Surrealist work presents an ordinary cup, saucer, and spoon lined with fur from a Chinese gazelle, which has been placed so that fur emphasizes the round shape of the cup and the spoon. The work confounds sensual pleasure, as the tactile nature of the fur both attracts the touch of the hand and repeals the mouth, the pleasure of drinking from the cup stymied. Following the Museum of Modern Art's 1936-37 exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Alfred H. Barr Jr., the director, noted, "Few works of art in recent years have so captured the popular imagination... The 'fur-lined tea set' makes concretely real the most extreme, the most bizarre improbability."

Oppenheim first unveiled this work at the Exposition surréaliste d'objets in 1936, and it was subsequently shown in London and later New York. Breton saw the work as exemplifying Surrealism's aim to "hound the made beast of function," and Max Ernst noted the work's significance with a tone of wry rivalry, "Who covers a soup spoon with precious fur? Who has outpaced us? Little Meret." Subsequently, as art critic Alexxa Gotthardt wrote, the pioneering work "began to assume its position as a tantalizing expression of Surrealist ideals: a sculpture that joined incongruous parts to create an impossible, uncanny object."

When the Museum of Modern Art purchased this work in 1936, it marked the first time the museum had purchased a work by a female artist. In addition to being an important example of Surrealism, the work is also a significant precursor of the Feminist Art movement.

Fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon - The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

Untitled (Soap Bubble Set)

This shadow box, Cornell's first effort in the signature Assemblage for which he is famous, combines a bird's egg, a doll's head, a fluted glass, a soap bubble pipe, and four cups, displayed against a print of the moon's geography. The wood and glass planes dividing the box create a sense of geometric order, framing the soap bubble pipe and the moon, images of elevation and flight, within the box's confined space. As art critic Olivia Laing noted of Cornell, "In his own artwork, which he didn't begin until he was almost 30, he made obsessive, ingenious versions of the same story: a multitude of found objects representing expansiveness and flight, penned inside glass-fronted cases."

Influenced by Max Ernst's La Femme 100 Têtes (1929), Cornell began to make collages in the early 1930s. He associated with the leading Surrealists and exhibited in the 1932 Surréalisme show. This work was made for MoMA's 1936 Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism. As art critic Jonathan Jones wrote, "From his collections of glass swans, Baedeker guidebooks, clay pipes, compasses and other suggestive souvenirs of the day before yesterday he invented a new kind of art." Cornell's boxes are at once thoroughly avant-garde, with their connections to the then-current Dada and Surrealism, as well as nostalgic memories of the past, with their allusions to old film actresses, dove cotes, and children's pastimes.

While he was well-known among New York avant-garde artists in the 1930s and 1940s, Cornell's work was only fully recognized in the 1960s, when the Guggenheim Museum held a retrospective in 1967. As Laing noted, "Cornell is seldom given his due in art-history textbooks, which tend to repeat the familiar post-war narrative in which Robert Rauschenberg and his 'Combines' (Monogram, 1955-59) launched the junk-into-art aesthetic in America.... Yet Cornell directly inspired Rauschenberg's early use of found objects.... 'The only difference between me and Cornell,' Rauschenberg once told me, 'is that he put his work behind glass, and mine is out in the world.'"

Wood, glass, plastic, paper, box construction - Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut

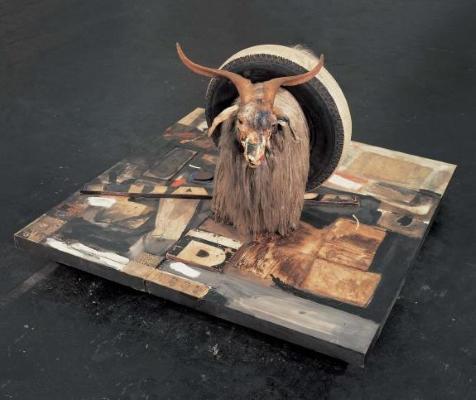

Monogram

This famous Assemblage improbably combines a taxidermied Angora goat, wearing a tire around its mid-section, with an abstract painting that includes a tennis ball and strips of wood. The work was prompted by Rauschenberg's discovery of the goat in a used furniture store, though he spent four years working out the possible combinations before deciding to attach the goat to the horizontal painting as if it were a pasture. The work evokes surprise and incongruity, as Rauschenberg said, "I wanted to use the surprise.... So the object itself was changed by its context and therefore it became a new thing." The effect of the surprising combination is made more compelling by its use of undeniably real materials, as the artist said, "I think a picture is more like the real world when it's made out of the real world."

The work is a culmination of Assemblage's early history, with its combination of readymades, evoking Duchamp, and its wooden platform painting, evoking Schwitters' Merz. As Frances Morris, director of Tate Modern said, "Rauschenberg is one of those artists who, in the decade after the second world war, truly transformed the nature of artistic practice, smashing through the boundaries of different media." A leader of what was later dubbed Neo-Dada, Rauschenberg called such works "combines," hybrids of sculpture and painting. His work influenced subsequent movements, including Conceptual Art, Performance Art, and the 1980s Young British Artists, including Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin.

Oil paint, paper, fabric, printed reproductions, metal, wood, rubber shoe-heel, and tennis ball on two conjoined canvases with oil on taxidermied Angora goat with brass plaque and rubber tire on wood platform mounted on four casters - Moderna Museet, Stockholm

Sky Cathedral

Nevelson's Assemblage made of boxes and three-dimensional objects towers against a wall and is painted monochromatically black, giving it a pictorial quality. The allover color minimizes the depth of the objects, but the curving and geometric shapes both extend outward and recede inward, creating inky black entrances and crevices as if the work were the improbable edifice its title indicates. Nevelson salvaged these boxes, pieces of wood, spindles, dowels, architectural ornaments, and moldings from various construction sites in New York City before gluing and nailing them together. Nevelson said, "When I look at the city from my point of view, I see New York City as a great big sculpture." But as much as the Assemblage recalls New York architecture, the monumental work also evokes other mysterious spatial and spiritual realms. By painting the piece black, she unified the individual components and erased their past histories, as she described, black "is the total color. It means totality. It means: contains all."

It is clear that Nevelson carefully arranged the items in each of the smaller boxes creating intuitive and suggestive compositions, but she later denied being interested in the individual boxes. Initially, the boxes were not nailed together, and the arrangement of the stacked boxes was variable, changing each time it was installed, although eventually Nevelson became more particular about fixed arrangements.

With its scale, monochromatic color, and allover composition, Nevelson's work can be seen as a sculptural response to Abstract Expressionist painting that dominated her era, but it also challenges Clement Greenberg, champion of Abstract Expressionism, who emphasized flatness and media specificity, as the work's three dimensionality blurs the distinction between sculpture, painting, and installation. While she eschewed feminists labels, Nevelson's work was a primary influence upon subsequent artists, such as Eva Hesse and later feminists, and also influenced the development of Installation Art in the late 1960s.

Painted Wood - The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

Homage to New York

This mechanical and kinetic Assemblage is composed of various found objects, including a piano, a go-cart, and a bathtub, along with autonomous motors, scrap metal, and mechanical wheels. The monumental work, standing twenty-seven feet tall and originally painted white, was meant to be set into clanking angular motion, providing a spectacle for the audience, before self-destructing in an explosion, triggered by a control button. According to the Museum of Modern Art, "During its brief operation, a meteorological trial balloon inflated and burst, colored smoke was discharged, paintings were made and destroyed, and bottles crashed to the ground. A player piano, metal drums, a radio broadcast, a recording of the artist explaining his work, and a competing shrill voice correcting him provided the cacophonic sound track to the machine's self-destruction - until it was stopped short by the fire department." Indeed, a mechanical misfire, 27 minutes into the performance, sparked a fire that destroyed the machine except for a fragment, now in the Museum of Modern Art's collection.

Tinguely pioneered mechanized kinetic Assemblage. As he wrote, "Everything moves continuously. Immobility does not exist. Don't be subject to the influence of out-of-date concepts. Forget hours, seconds, and minutes. Accept instability. Live in time. Be static - with movement." The innovative work also emphasized collaboration, as he worked with engineers, most notably Billy Klüver, and artists, including Robert Rauschenberg who contributed his Money Thrower, which threw silver dollars into the crowd at one point in the performance.

Tinguely's concepts have become fundamental to contemporary art, as his influence can be seen in the works of Joep van Lieshout and Jordan Wolfson, as well as popular events, such as the Burning Man Festival, and art projects created by Survival Research Laboratories in San Francisco.

Found objects, motorized elements - The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

The Liberation of Aunt Jemima

In this Assemblage, an Aunt Jemima figurine, commonly sold as a pencil and notepad holder to housewives, transformed into a revolutionary, as she holds a rifle in her hand in addition to a broom and stands amidst a carpet of cotton. The "mammy" figure emerged in the United States in the late 1800s and was a grotesque stereotype of black women that was used to sell home goods to women who worked in the home. Standing in front of wallpaper displaying ads for Aunt Jemima syrup, the figure holds a postcard in front of her. As Saar described, "In front of her, I placed a little postcard, of a mammy with a mulatto child, which is another way black women were exploited during slavery. I used the derogatory image to empower the black woman by making her a revolutionary, like she was rebelling against her past enslavement."

The glass vitrine, recalls Joseph Cornell's surrealist shadow boxes, which she encountered in a 1967 Pasadena Art Museum exhibition, as well as Andy Warhol's gridded, Pop Art screen prints of Marilyn Monroe and other celebrities. In this early work, she turns her influencers into a work of social and political protest. Subsequently, she began collecting racist and derogatory items at local yard sales, and noted, "My work started to become politicized after the death of Martin Luther King in 1968. But The Liberation of Aunt Jemima...was the first piece that was politically explicit. There was a community center in Berkeley, on the edge of Black Panther territory in Oakland, called the Rainbow Sign. They issued an open invitation to black artists to be in a show about black heroes, so I decided to make a black heroine." In 1960s Los Angeles, a number of African American artists turned to Assemblage, including David Hammons and John Outterbridge. They saw in it a way to bridge not only art and life, but the personal and the political, appropriating (and re-appropriating) racist images and objects and giving them new meanings. As art historian Caroline A. Miranda writes, "In Saar's hands...these notorious artifacts became something mighty," and the noted activist Angela Davis credits this work as the beginning of the black women's movement. Saar's work continues to attract contemporary attention, as seen in her 2019 solo exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art.

Mixed media - University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, California

Long Term Parking

This monumental work, standing 50 feet high, is an Assemblage of 60 cars embedded in concrete. Made of 40,000 pounds of concrete, the work, as art critic Nessia Pope writes, "makes evident the undeniable mass of objects and our relationship to them by underlining the proportions of the cars and of the column they composed with that of a human being."

In 1960, Arman began developing Assemblages that he called "accumulations," which according to Pope, transformed the objects "into a new amalgamated object - a unique kind of sculpture." His works ranged from a collection of gas masks in a Plexiglas case to his famous and controversial Full Up (1960), where he filled the Galerie Iris Clert with trash collected from the Paris streets. With Long Term Parking, he also pioneered the use of Assemblage as public art. As he noted, "The perfect knowledge of the visual impact of objects is a part of my work. I have a very simple theory. I have always pretended that objects themselves formed a self-composition. My composition consisted of allowing them to compose themselves."

To make this work he selected the various cars, almost all by French auto makers, by noting particular cars he saw driving by and then finding the same model in a junkyard. Before embedding the cars in concrete, they were restored and painted to enhance their visual effect. Over time, the pigments have faded, and exposed elements have begun to suffer some corrosion, reflecting Arman's view that over a long period of time, the cars would eventually began to collapse, leaving their empty space in the concrete as a wry comment on the disposable nature of consumer culture. His accumulations profoundly influenced subsequent artists, including Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, and Martha Rosler.

Automobiles in concrete - Chateau de Montcel, Jouy-en-Josas, France

Meta-Monumental Garage Sale

Ordered for the flow of traffic, this "garage sale" at New York's Museum of Modern Art includes neat rows of used furniture, display tables, two tents housing other items, a car, and a multitude of objects hung on the walls, from clothing to prints. A large flag and a sign reading "SAVE MONEY $" with an arrow painting down hang from the upper floor. Here, the Assemblage of disparate elements are not composed into a single work of art, but instead arranged separately in a large space, creating more of an installation to walk through than a sculpture to behold. Rosler supervised the event, for which she had also hired performance artists and actors to work the floor, and produced two issues of a pamphlet, including fake coupons made to resemble a newspaper. As Rosler noted, "The garage sale is about social and economic relations. It is a performance with an accompanying 'soundtrack.' Most visitors don't look beyond the fun and the bargains. That is why we needed this publication to function as it did, to offer news, history, notes, and critique. The themes of the two issues were The Social Lives of Objects and Work, Value, and Waste."

Rosler held her first garage sale, the Monumental Garage Sale, in 1973, and said it "was prompted by my interest in commodity fetishism in the suburban world I was now inhabiting.... [It]... was as much about social transactions as about the exchange of money for goods." Reprised frequently, and also reconfigured as her Traveling Garage Sales, Rosler's use of Assemblage masterfully challenges aesthetic categories and assumed boundaries between art and life. As art critic Randy Kennedy noted, the Meta-Monumental Garage Sale was not a usual garage sale, but "a piece of performance art in which a garage sale is enacted." But the items are sold, making the event, as Rosler said, "...not symbolic activity. It's real activity. Like most things, it has symbolic dimensions. But it is what it is."

Various items

My Bed

This controversial and iconic work consists of the artist's bed, linens strewn and stained, along with various items, including empty liquor bottles, used condoms, old newspapers, slippers, and underwear. Conveying an emotional rawness and plucked from real life, here Assemblage takes on a confessional quality in an installation that also shocks. As art critic Jonathan Jones wrote, Emin's works "remain flat, unredeemed; she transfigures nothing. But in many ways Emin's achievement is the same as Caravaggio's: she rubs our noses in reality, in a way that subverts all our illusions, fantasies, snobberies and repressions, those barriers we put up between us and death." In assembling these items, Emin does not transfigure them into something more aesthetic or artful but insists that the viewer confront them for what they are and how that might make for discomfort.

Emin said the work was "a self-portrait, but not one that people would like to see." She explained the origins of the work: "I had a kind of mini nervous breakdown in my very small flat and didn't get out of bed for four days." When she was finally able to crawl out of bed, she described, "And then I thought, 'What if here wasn't here? What if I took out this bed...and placed it into a white space? How would it look then?' And at that moment I saw it, and it looked fucking brilliant. And I thought, this wouldn't be the worst place for me to die; this is a beautiful place that's kept me alive."

Noting how the work evokes Rauschenberg's Bed (1955), Jonathan Jones described Emin's innovation: "By lucky chance I saw Rauschenberg's Bed again in New York a few weeks ago. In fact, the comparison helped me understand Emin's originality. Rauschenberg's bed is splattered with paint and...hangs on the wall.... Rauschenberg makes it quite clear that a transformation has taken place. Emin's bed, by contrast, has no aesthetic additions... it is just there, a messy fact, and a decade on, refuses to be anything else. It now looks like one of the truly great readymades."

Shown at the Sagacho Exhibition Space in Tokyo in 1998, this work became iconic and exemplary of Young British Artists's emphasis on shock and spectacle, and later led to her being shortlisted for the Turner Prize. Emphasizing a messy and autobiographical reality, her work has redefined Assemblage for contemporary artists such as Song Dong and Tokomo Takahashi, whose installations include accumulations of autobiographical objects, displayed in their original chaos.

Box frame, mattress, linens, pillows and various objects - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Beginnings

Historical Influences

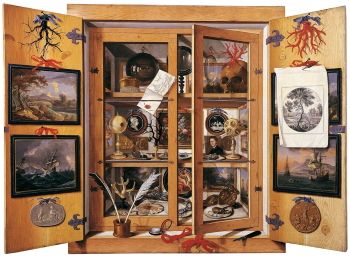

The avant-garde development of Assemblage drew upon long-standing cultural and artistic trends, dating back to the Renaissance. By the late 1500s, curiosity cabinets were popular among the aristocratic class, as shown by Gabriel Kaltemarckt's advice that a collection should include "curious items from home or abroad" and "antlers, horns, claws, feathers...belonging to strange and curious animals." Some collectors went so far as to combine taxidermied animal parts to create fantastical creatures. Such collections, essentially containing found objects and readymades, became de rigeur symbols of intellectual and cultural distinction. Curiosity cabinets, often on a more intimate scale, subsequently became popular among the middle class and were often found in Victorian homes.

In 1482, Carlo Crivelli included a gold key on an actual cord in his depiction of Saint Peter in his Madonna and Child with Four Saints (1482). Though Crivelli's inclusion was somewhat novel, small, precious items were often used to enhance religious or secular objects. In the late 1890s, Antonio Mancini, an Italian painter best known for his impasto Impressionist works, at times included found materials, such as pieces of glass or tin foil and, in one painting of a clarinet, the instrument's keys. According to art historian William C. Seitz, the Italian Futurist Gino Severini began using found materials in his painting after talking with the French critic Guillaume Apollinaire about similar methods used in Italian fifteenth-century paintings.

Pablo Picasso and Umberto Boccioni

Traditionally, Pablo Picasso's Still-Life with Chair Caning (1912) is often credited as both the first collage and the precursor of Assemblage as it incorporates oilcloth and an ordinary piece of rope into the painting's composition. However, it should also be noted that by 1911 the Italian Futurists were exploring Assemblages, creating what they called "object sculptures."

As art historian William C. Seitz noted, Umberto Boccioni's "Fusion of a Head and a Window...which included a real wooden window frame and fastener was done in 1911 or perhaps 1912, the year of the first collages of Picasso and Braque." The leader of Futurism, Filippo Marinetti noted Boccioni used "materials that were totally different as far as weight and tactile value: iron, porcelain, and female hair." In the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture (1912) Boccioni advocated for a stunning inclusion of found materials, writing, "even twenty different materials can compete in a single work to effect plastic emotion. Let us enumerate some: glass, wood, cardboard, iron, cement, horsehair, leather, cloth, mirrors, electric lights, etc., etc." Futurist works of Assemblage were subsequently lost or destroyed and their impact overshadowed by Picasso's work in the genre, but their work influenced the Russian Constructivists, including Vladimir Tatlin.

In 1913, Apollinaire published images of several of Picasso's constructions in his journal Les Soirées de Paris. As art historian Jackie Heuman noted, the works "provoked uproar.... Criticism was based on the desultory finish, the use of ignoble materials and on the perceived inappropriateness of the subject matter. This hostile response may have expressed a sense that the sculptural canon was being subverted by popular culture. When asked whether the constructions were sculptures or paintings, Picasso replied: 'Now we are delivered from Painting and Sculpture, themselves already liberated from the imbecile tyranny of genres. It's neither one thing nor another.'" This blurring of genres became fundamental in the practice and theory of Assemblage.

Readymades

Many Assemblage artists trace their interest in the technique back to the Dadaist Marcel Duchamp and his "readymades." In 1913, Duchamp combined a bicycle wheel and a common stool to create Bicycle Wheel, which he cited as his first readymade, when he coined the word in 1915. Subsequently, the use of readymades, ordinary objects that are mass produced, and found objects, which can include natural objects such as feathers, butterfly wings, or bits of wood, became an integral part of Assemblage. As New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art's Nan Rosenthal wrote, "His most striking, iconoclastic gesture, the readymade, is arguably the century's most influential development on artists' creative process.... The object became a work of art because the artist had decided it would be designated as such." In many ways, Duchamp's insistence that the artist - not critic or curator - is responsible for defining what art is opened the door for other artists to expand notions of art beyond what had previously been imagined. From the beginning, Assemblage art questioned the canons that had been put in place by critics and art historians.

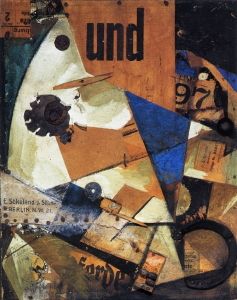

Dada

As art historian William C. Seitz noted, "the admixture of Dada in assemblage must not simply be granted; it must be insisted upon." Developing in the aftermath of World War I and rejecting traditional political and social structures as absurdities that had led to the war, Dada emphasized an "anti-art" or anti-aesthetic approach to art. Ardently embracing experimentation, artists like Hannah Höch, John Heartfield, and Raoul Hausmann, transformed collage into pioneering forms of photomontage and Assemblage. Additionally, artists like Max Ernst and Hans Arp engaged ideas of chance in their collages and assemblages. By 1918, Kurt Schwitters scavenged scrap materials and trash to incorporate into works that he called Merz, a term he explained both as a nonsense word and derived from the second syllable of the German word "commerce." As Seitz further noted, Schwitters "occupies a position of special honor in the history of assemblage.... It was he who conceived of an embracing medium that included painting, collage, agglomerate sculpture."

Surrealism

Dada assemblage was subsequently adopted by the Surrealists to create uncanny objects. Man Ray, who was associated with both movements, glued tacks to an iron to create Cadeau (Gift) (1921), while Meret Oppenheim's Object (1936) is a teacup, saucer, and spoon wrapped in fur. Provoking subconscious realities and desires, Surrealist Assemblage echoed André Breton's suggestion: "Recently I suggested that as far as is feasible one should manufacture some of the articles one meets only in dreams."

Influenced by Max Ernst but distancing himself from Surrealist ideas of the subconscious, the American artist Joseph Cornell pioneered Assemblage in the United States with his shadow boxes in the mid-1930s. Described by art critic Jonathan Jones as "a new kind of art," Cornell's shadow boxes, known for their evocative juxtapositions of objects, had a noted impact on a diverse range of subsequent artists, including Arman who used glass display boxes and cubes for his accumulations of detritus and Betye Saar who adopted the shadow box to social and political critique.

International Trend: 1950s and Beyond

In the 1950s, Assemblage came of age, its potential fully developed by leading international artists in a number of movements. Neo-Dada, Arte Povera, Nouveau Réalisme, and Pop Art fully exploited the artistic potential of Assemblage, expanded its scale, ambition, and approach. Neo-Dadaist Robert Rauschenberg created Assemblages that he termed "combines," while Arman in the Nouveau Réalism movement pioneered what he called "accumulations," collections of objects that expanded into Installation Art and Public Art. Jean Tinguely created mechanized and motorized Assemblages that pioneered Kinetic Art. At the same time, artists not strongly associated with a particular movement also pioneered new approaches, as seen in Louise Nevelson's assembled wood sculptures. In 1961, the Museum of Modern Art in New York mounted an exhibition entitled The Art of Assemblage, curated by William Seitz, and as art critic Alexander Glover wrote, "It would go on to establish the art of Assemblage as a global phenomenon and one that was indulged in by well-known artists."

Concepts and Styles

Assemblage and African Art

Following colonial conquest, many African sculptures and masks were imported to Europe in the 1800s. Viewed as artifacts rather than artworks, some were displayed in various museums, including the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris, while other items were often sold for very little. These works had a profound influence on avant-garde artists and movements beginning in the early 1900s, lending to the trend of Primitivism. In 1906, Henri Matisse bought a small Vili figure and showed it to Picasso, prompting his many visits to the African art collection at the Trocadéro. African art, while exhibiting a wide range of styles and techniques originating in specific tribal cultures, often incorporated various materials, including cowrie shells, leather, feathers, metal nails, raffia and other plant fibers, and bits of glass or metal. As art historian Jackie Heuman wrote, Picasso's "constructions were launched at a time when Picasso had become deeply interested in tribal art. Ethnographic artifacts use a mélange of materials, including found objects, and their presence undoubtedly had a profound influence on him." This influence continued among subsequent generations of artists, including Arman, who had a museum-quality collection of African art.

Blurring the Boundaries

From the beginning, Assemblage blurred boundaries between art and the reality of everyday life and explicitly challenged the traditional separation of genres. Referencing Picasso's Still Life (1914), a work that includes found pieces of wood, a shelf, and table tassels, art historian Jackie Heuman wrote, "The admission into the work itself of selected but otherwise untransformed fragments of the real world meant that art was not only addressing the everyday but being visibly invaded by it, challenging the concept of art as something precious and valuable." Duchamp's readymades also questioned the tradition of Western sculpture, the insistence on originality, and the nature of authorship, while Kurt Schwitter's Merz works envisioned an art encompassing all genres in one immersive environment, as seen in his Merzbau (1923-37). The trend became dominant in the 1950s, expressed in works like Rauschenberg's "combines," which combined sculpture and painting, and flew in the face of art critic Clement Greenberg's championing of media specificity as well as Abstract Expressionism.

Innovation

Originating in experimentation, Assemblage played a notable role in innovating other artistic approaches, including Kinetic Art, Installation Art, Environmental Art, and Performance Art. Schwitter's Merzbau (1923-37), an early example of an Installation, influenced artists, such as Richard Hamilton. Hamilton, along with other artists from The Independent Group, collaborated on room installations for the 1956 exhibition This Is Tomorrow. In time, Assemblages became vast "accumulations," as seen in Arman's Le Plein (Full Up) (1960), for which he filled a Parisian gallery with trash, and Allan Kaprow's Yard (1961), consisted of a sculpture garden filled with tires. Such works also emphasized audience interaction in diverse ways, and exhibitions became events, performances, and happenings. Unveiled at the Museum of Modern Art, Yves Tinguely's performance Homage to New York (1960) was a self-destructing sculpture, whose remnants audience members were to pick up as souvenirs, and is a touchstone of Kinetic Art. Christo's increasingly monumental Assemblages in the 1960s helped to spur the trend of Environmental Art. In 1966, Allan Kaprow's book Assemblage, Environments & Happenings became a foundational text, not only definitively describing contemporary developments, but also influencing subsequent artists.

Later Developments

Assemblage, as art critic Alexander Glover notes, "is still influential and prevalent among today's contemporary artists," though it often subsumed as a technique in works defined as installations. Conceptual, Neo-Pop, and the Young British Artists widely adopted Assemblage, while leading artists of the 1950s and 1960s continue to masterfully explore the technique. For instance, Martha Rosler's Monumental Garage Sale (1973) and Meta-Monumental Garage Sale (2012) were advertised as garage sales in local papers and as a performance in the art press.

A new generation of artists uses Assemblage in large-scale installations, as seen in Tokomo Takahashi's Clock Work (2010), her third reprisal of a 1998 work, and Song Dong's 2009 Museum of Modern Art installation of fifty years' worth of objects hoarded by his mother. Assemblage also reflects a contemporary ethos of reusing and recycling. Maha Mullah, whose sculpture Food for Thought Almuallaqat (2014) assembled a large number of used Saudi Arabian aluminum pans, said, "I don't see the point in creating new objects while we have a lot of waste around us." Gabriel Orozco, Fishli/Weiss, Mike Nelson, and Christina Mackie are just a few of the contemporary artists noted for installations, assembling found objects and scavenged materials.

Useful Resources on Assemblage

-

![Kurt Schwitters: Merzbau 2013]() 8k viewsKurt Schwitters: Merzbau 2013BAMPFA

8k viewsKurt Schwitters: Merzbau 2013BAMPFA -

![Contemporary Responses to Kurt Schwitters | TateShots 2013]() 6k viewsContemporary Responses to Kurt Schwitters | TateShots 2013

6k viewsContemporary Responses to Kurt Schwitters | TateShots 2013 -

![Meret Oppenheim. Retrospektive. Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin 2013]() 6k viewsMeret Oppenheim. Retrospektive. Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin 2013

6k viewsMeret Oppenheim. Retrospektive. Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin 2013 -

![Mark Stokes - Joseph Cornell: Worlds in a box]() 74k viewsMark Stokes - Joseph Cornell: Worlds in a box

74k viewsMark Stokes - Joseph Cornell: Worlds in a box -

![Robert Rauschenberg - Pop Art Pioneer Full BBC Documentary 2016]() 530k viewsRobert Rauschenberg - Pop Art Pioneer Full BBC Documentary 2016

530k viewsRobert Rauschenberg - Pop Art Pioneer Full BBC Documentary 2016 -

![Assemblage and Politics (Modern Art in Los Angeles)]() 3k viewsAssemblage and Politics (Modern Art in Los Angeles)Getty Research Institute

3k viewsAssemblage and Politics (Modern Art in Los Angeles)Getty Research Institute -

![Hunters & Gatherers: The Art of Assemblage]() 29k viewsHunters & Gatherers: The Art of AssemblageOur PickSotheby's

29k viewsHunters & Gatherers: The Art of AssemblageOur PickSotheby's -

![Betye Saar: The Liberation of Aunt Jemima]() 52k viewsBetye Saar: The Liberation of Aunt Jemima

52k viewsBetye Saar: The Liberation of Aunt Jemima -

![Tracey Emin on My Bed | TateShots]() 69k viewsTracey Emin on My Bed | TateShots2015

69k viewsTracey Emin on My Bed | TateShots2015 -

![Martha Rosler's Meta-Monumental Garage Sale at MoMA 2012]() 2k viewsMartha Rosler's Meta-Monumental Garage Sale at MoMA 2012

2k viewsMartha Rosler's Meta-Monumental Garage Sale at MoMA 2012 - Jean Tinguely, Homage to New York, 1960Our Pick

- Audio. Robert Breer. Homage to Jean Tinguely's Homage to New York. 1960

- Louise Nevelson Sky Cathedral videoOur Pick

-

![ART EXPLAINED | Robert Rauschenberg Monogram at Tate Modern]() 5k viewsART EXPLAINED | Robert Rauschenberg Monogram at Tate ModernTalk by Sarah Phillips

5k viewsART EXPLAINED | Robert Rauschenberg Monogram at Tate ModernTalk by Sarah Phillips -

![Inside 'Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust" 2015]() 6k viewsInside 'Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust" 2015Our PickRoyal Academy of Arts / Sarah Lea

6k viewsInside 'Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust" 2015Our PickRoyal Academy of Arts / Sarah Lea -

![Assemblage]() 88k viewsAssemblageOur PickMOCA / Artists George Herms and Betye Saar and MOCA Chief Curator Helen Molesworth

88k viewsAssemblageOur PickMOCA / Artists George Herms and Betye Saar and MOCA Chief Curator Helen Molesworth -

![Betye Saar interview]() 10k viewsBetye Saar interviewNetropolitan Artsconversations

10k viewsBetye Saar interviewNetropolitan Artsconversations -

![Art and everyday life]() 2k viewsArt and everyday lifeLecture by Martha Rosler 2014 / lisbonconsortium

2k viewsArt and everyday lifeLecture by Martha Rosler 2014 / lisbonconsortium -

![Assemblage - Sculpture: Jeremy Mayer at TEDxGoldenGatePark (2D)]() 29k viewsAssemblage - Sculpture: Jeremy Mayer at TEDxGoldenGatePark (2D)TEDx Talks November 29, 2012

29k viewsAssemblage - Sculpture: Jeremy Mayer at TEDxGoldenGatePark (2D)TEDx Talks November 29, 2012 -

![The Art of Assemblage - George Herms | Agathe Snow - MOCA U - MOCAtv]() 18k viewsThe Art of Assemblage - George Herms | Agathe Snow - MOCA U - MOCAtvMOCA

18k viewsThe Art of Assemblage - George Herms | Agathe Snow - MOCA U - MOCAtvMOCA -

![HANNELORE BARON : A COLLAGE AND ASSEMBLAGE EXHIBITION]() 25k viewsHANNELORE BARON : A COLLAGE AND ASSEMBLAGE EXHIBITIONERIC MINH SWENSON

25k viewsHANNELORE BARON : A COLLAGE AND ASSEMBLAGE EXHIBITIONERIC MINH SWENSON - Sunday at the Met - Robert Rauschenberg: CombinesOur PickConversation with Robert Rauschenberg and Calvin Tomkins