Summary of George Grosz

George Grosz is one of the principal artists associated with the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement, along with Otto Dix and Max Beckmann, and was a member of the Berlin Dada group. After observing the horrors of war as a soldier in World War I, Grosz focused his art on social critique. He became deeply involved in left wing pacifist activity, publishing drawings in many satirical and critical periodicals and participating in protests and social upheavals. His drawings and paintings from the Weimar era sharply criticize what Grosz viewed as the decay of German society. Shortly before Hitler seized power, Grosz moved to America to teach art and thus avoided Nazi persecution when his work was deemed "degenerate." His later style changed sharply due to his loss of faith in humanity, shifting from political propaganda to caricatures of the inhabitants of New York City and romantic landscapes. The traumatic experiences that drove George Grosz to rally against war, corruption, and what he saw as an immoral society created a particularly affecting and indelible artistic legacy. As a symbol of the revolution in Germany, his art was instrumental in awakening the general public to the reality of government oppression.

Accomplishments

- George Grosz honed his skill for satire in his early illustrations of Berlin night-life while still an art student. He combined his skill for draughtsmanship with the influence of Cubist and Futurist modes of representing space to create an individual, yet objective social-realist style that could accurately convey his critical vision of contemporary society.

- The figures that inhabit Grosz's art are typically not specific individuals, but rather allegorical figures representative of the different classes and the various plights of German society between the world wars. The use of allegory allowed Grosz to present a biting critique of this society without straying too far from the ideal of portraying a modern vision of reality.

- Grosz synthesized two distinct and long-standing traditions within German art history with his own perspective to create his unique style. Combining the linear quality of the historic graphic tradition with German Gothic art's penchant for brutally grotesque imagery, Grosz utilized these traditional modes to add further emphasis to his contemporary moral perspective.

- Grosz's most critical works are typically executed in pen and ink, and occasionally he worked into them with watercolors. Many of his drawings were reproduced in periodicals and journals, which circulated Grosz's images among various radical groups and the working class. The immediacy of these drawings and their reproductions allowed them to clearly convey Grosz's commentary on the modern world to a more diverse audience than a singular painting in a gallery or museum could.

Important Art by George Grosz

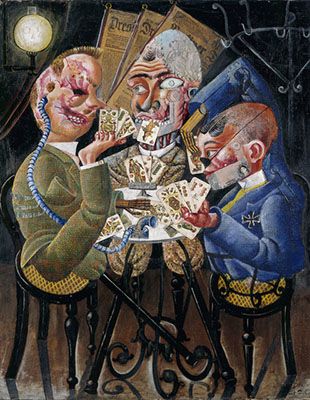

The Faith Healers

This work, also known by the title Fit for Active Service, depicts a doctor inspecting a skeleton with an ear trumpet, pronouncing him "KV" (short for kriegsverwendungsfahig, or "fit for combat"). Unconcerned with the diagnosis, the surrounding officers appear either bored or absorbed in other matters. The scene refers to the desperate recall of discharged soldiers toward the end of war, after the German forces suffered heavy losses. Grosz himself had been forced to return to the front in 1917, only to be released four months later for mental illness, lending the subject a great deal of personal significance. Grosz's penchant for grotesquerie is indebted to the precedent set by the German Gothic tradition, which he often looked to as a source of inspiration. Grosz is best known for his drawings and works on paper, and The Faith Healers is an exemplary work of his highly politically charged style that overlaps with the ideals of both Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) and the Berlin Dada group.

Ink and brush - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

A Funeral: Tribute to Oskar Panizza

Dedicated to the writer and psychiatrist Oskar Panizza, who was known for his witty criticisms against the state, A Funeral is a statement of Grosz's feelings of disgust and frustration toward German society during the tumult that followed World War I. The chaotic procession of distorted figures, painted in shades of dark red and black, seems to take place in a hellish chasm between precariously slanted buildings. The dense, collage-like technique, which draws from Cubism and Futurism, adds to the sense of claustrophobia by layering multiple scenes in a shallow space. In a letter, Grosz described his composition as a "gin alley of grotesque dead bodies and madmen.... A teeming throng of possessed human animals... think: that wherever you step, there's the smell of shit." This vivid description conveys Grosz's passionate opposition against the direction of the German administration following World War I. The synthesis of inspiration from both modern and traditional sources is typical of Grosz's work as well as that of the larger Neue Sachlichkeit movement.

Oil on canvas - Stattsgalerie Stuttgart, Germany

Daum Marries Her Pedantic Automaton "George" in May 1920. John Heartfield is very glad of it.

After several years of courtship, Grosz married Eva Peter, whom he met while taking classes at the School of Arts and Crafts in 1916. Nicknamed Maud (the anagram of "Daum") by Grosz, her character appears hesitant, even afraid, despite her seductive state of undress. Grosz is depicted as a robot, a central Dadaist motif that redefined the artist as machine. Wieland Herzfelde, the publisher of many of Grosz's portfolios, attempted to unravel the subject of the painting by explaining marriage as a condition that "comes between the bride and groom like a shadow, this fact that, at the very moment when the wife is allowed to make known her secret desire and reveal her body, her husband turns to other soberly pedantic arithmetical problems..." Grosz emphasized the cold, impersonal quality of the automaton with his use of collage. The anonymous - but oddly constructed background furthers the sense of alienation, a common theme in modernist art of the early-20th century - but here that lack of emotion is not necessarily a negative quality.

Pencil, pen, brush and ink, watercolor and collage - Berlinische Galerie, Berlin Landesmuseum fur Moderne Kunst

Germany: A Winter's Tale

Germany: A Winter's Tale, is close in style and composition to A Funeral: Tribute to Oskar Panizza(1917-18), which was created in the same time period. Both reference the shattered space of Cubism and the motion of Futurism. Grosz utilizes allegory throughout in order to maximize the impact of each figure and object within the tumultuous space of the painting. In the center, a man representative of the bourgeoisie readies himself to consume a meal, while a riot of bodies swirls around his head. The three figures at the bottom represent the church, state, and school, all of which spoon-feed their ideals to the receptive man. Those in control studiously ignore the resulting chaos, represented by figures such as the sailor, who Grosz declared to be a symbol of revolution. A Winter's Tale was named after a poem by Heinrich Heine, a darkly comedic work that was banned at the time of its 1844 publication due to its perceptive criticism of German society. Grosz acknowledged the German tradition of critical literature and aligned it with the visual arts tradition, while presenting a modern visual satire.

Oil on canvas - Whereabouts unknown

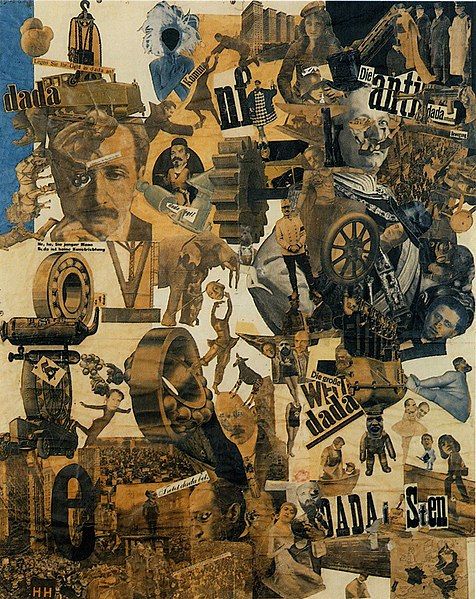

Life and work in Universal City, 12:05 Noon

George Grosz and John Heartfield collectively founded photomontage, the practice of cutting up and piecing together different photographs and re-photographing the result to make an entirely new image. In this joint effort by both artists, Grosz's original sketches have been obliterated by an explosion of collaged images that make reference to popular culture in the United States, or the "Universal City." Although meant to be illogical and random, the composition is organized into a procession of figures moving from the upper right to the lower left and set against a row of tall buildings, similar to A Funeral: Tribute to Oskar Panizza(1917-18). This compositional relationship suggests the Dadaist construction of Life and Work in Universal City was actually the result of a natural stylistic progression from Cubism and Futurism, utilizing modernist visual techniques in a new medium with a highly critical message.

Collage

Shut Your Mouth and Keep on Serving

Intended to criticize the bourgeoisie for their eagerness to go to war again while professing to worship the "Prince of Peace," Shut Up and Keep on Serving is a blatant accusation of hypocrisy. The image led to a trial against Grosz and his publisher, Wieland Herzfelde, who were both accused of blasphemy. Originating from set designs that Grosz created for a stage production of The Adventures of the Good Soldier Schwejk(1928), a popular satirical novel that takes place during World War I, the drawing was published as part of the Hintergrund portfolio(1928) on the day of the play's premiere. Photogravure, a print process that involves using a glass plate covered with a light-sensitive chemical, provided a cost-effective way to reproduce the drawing. This image chastises German society's march toward World War II, deploying religious imagery to incite anger in the viewer. The image and its message firmly align with the highly politicized publications of the Berlin Dada group, of which Herzfelde was the primary publisher. Reversing the historic tradition of Christian reverential art in Europe, Grosz uses the image of Christ for the modern means of social critique and judgment.

Drawing, Photogravure print reproduction - Schiller-Nationalmuseum, Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Marbach am Neckar

Peace, II

Painted the year after World War II ended, Peace, II, conveys Grosz's grim vision of the war's aftermath. Having witnessed the horrors of World War I in person, as well as its fallout while still in Germany, Grosz clearly held the pessimistic opinion that true peace could not be achieved in the modern world. Regarding the Treaty of Versailles and the resolution of WWI, he stated, "Peace was declared, but not all of us were drunk with joy or stricken blind." His view of humanity's tendency toward destruction proved true, and after a second World War, only his style had changed. This is one in a group of paintings that he executed during the war that shares similar apocalyptic imagery, swirling compositions, and haunting allegorical figures. He no longer satirized the bourgeoisie and capitalists, but instead portrayed a bleak future. Grosz presents the viewer with a central skeletal figure striding out of what remains of a bombed-out building, with detritus piled high on every side. The lone figure emerging from the depiction of a modern, 20th century hell-mouth comments on the outcome of war as well as the possibility of peace in the future. Grosz's art had shifted away from political content in his early years in New York, but he could not remain impartial during the travesty of World War II. This painting is far more expressionistic than any of his earlier work and is indebted to the tradition of Romanticism, evident in the dramatic composition that dwarfs the singular, grim figure striding amidst the rubble, the palette, and the jagged forms.

Oil on canvas - The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

Biography of George Grosz

Childhood

Georg Ehrenfried Groß was the youngest child born to Karl and Marie Wilhelmine Groß. He lived with his two older sisters in a Berlin public house, owned and managed by his parents, until the business failed in 1899. The family moved to Stolp, a rural town on the northeastern coast (now part of Poland), where Karl, a Freemason, had secured a position as the local lodge caretaker. His death in the following year compelled the Groß family to return to Berlin, where Georg's mother and sisters made a living by sewing.

Georg moved back to Stolp in 1902, when his mother obtained a job with the Hussars regiment. He enjoyed illustrations of war, having drawn pictures of horses and soldiers with his father at an early age, and gained further exposure through representations of historic battles and uniform sketches displayed in the officer's clubhouse. Georg's earliest known sketchbooks date to 1905, in which soldiers feature prominently, as well as the robbers, cowboys, and Indians gleaned from his favorite adventure stories. As he grew older, he continued to extract ideas from popular novels and magazines. Many of these stories took place in the Wild West, building an idealistic view of American culture in Georg's mind that persisted into adulthood.

Early Training

In 1908, Grosz was expelled from school for striking back after receiving punishment from a teacher. His drawing master, however, recognized his talents and helped him apply to the Dresden Academy of Art. At the academy, Grosz learned to be a skilled copyist by drawing plaster busts. His personal style developed outside of the classroom, strongly influenced by Jugendstil (Art Nouveau), magazines, and cartoon illustrations. He greatly admired illustrations in Ulk, the humorous supplement of the Berliner Tageblatt that also featured Grosz's first published drawing in 1910.

After graduating from the academy in 1911, Grosz moved back to Berlin. Looking to develop his work, he began to execute studies from life for the first time. He immersed himself in the pleasures of the city, drawing inspiration from café culture and nightlife. A growing interest in the macabre and the surreal also revealed itself in his drawings of circus performers and prostitutes. While attending the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts) in Berlin, Grosz documented the struggles of the working class in his sketches. Shielded by academic insularity from the influence of avant-garde groups such as Die Brucke and Der Blaue Reiter, these drawings were merely observations of reality rather than political commentaries. In 1913, Grosz spent several months in Paris at the Académie Colarossi. Although claiming to be unimpressed by the city, he became friendly with Jules Pascin, whose spontaneous artistic style and erotic nudes informed Grosz's later work.

Seeing the war stories of his childhood come to life in the beginnings of World War I, Grosz joined the army in 1914, but was discharged after six months due to sinusitis. Cynical drawings, such as The Faith Healers (1916), documented his own experiences as a soldier and clearly demonstrated the dissolution of his idealistic beliefs regarding war. In order to both distance himself from his German roots, and to proclaim his affinity for American culture, Georg Groß had his name legally changed to George Grosz in 1916. He was recalled to active duty in 1917, but was permanently released after an obligatory stay in a psychiatric facility. Disillusioned by a human predisposition for violence he observed during World War I, Grosz's drawings became even more explicit, expressing his shock and disgust. He was inspired by earlier political and social satirists like Honore Daumier and William Hogarth, and aspired to become the 20th-century German equivalent of these renowned artists. Along with his colleagues Wieland Herzfelde and John Heartfield, he joined the Communist Party of Germany and developed a political satire magazine called Die Pleite (Bankruptcy).

Mature Period

Grosz made his first painting sales in 1919, followed by a contract with Hans Goltz, a Munich dealer who represented him exclusively until 1922. His anti-war sentiments led to involvement in political discussion, in which he supported the Leftists. Also in 1919, Grosz joined the Dada movement in Berlin, as his critical view of German society aligned with their ideals. He participated in the first Dada publications, exhibitions, and actions. Grosz and Heartfield developed the medium of photomontage, creating images such as Life and Work in Universal City, 12:05 Noon (1920) that served as leftist propaganda. From his activities, Grosz became a revolutionary figure and had a warrant issued for his arrest by the conservatives during the 1919 Spartakus Revolution. He went into hiding for a time, but continued to draw satirical cartoons for Die Pleite (Bankruptcy) and other satirical magazines like Der Gegner (the Opponent).

Grosz's first one-man show took place at Goltz's Galerie Neue Kunst in 1920. In the same year, he married his longtime girlfriend, Eva Peter; the event was commemorated by the drawing Daum Marries Her Pedantic Automaton "George" in May, 1920. John Heartfield Is Very Glad of It (1920). Peter later collaborated with Grosz on erotic, macabre fantasies that often revisited the subject of Lustmord (sexual murder). Daum(1920) was exhibited at the First International Dada Fair (1920), along with a portfolio of satirical drawings entitled Gott mit uns (God with us)(1920). The organizers, including Grosz, were put on trial and fined for "grossly insulting the German army." Unfazed, Grosz continued to publish propagandistic materials against the establishment, including Ecce Homo(1915-22), another portfolio for which he was accused of pornography and fined. During the 1920s he was recognized internationally as one of Germany's most important artists who participated in social and political criticism. His renown brought change to his art as well as his life, as he received several portrait commissions, which he completed without any hint of scorn or derision for the sitters. Due to the increasing political instability in Berlin and his antagonistic relationship with the government, Grosz spent several months in Russia and the French Riviera in the mid to late 1920s, before accepting an invitation to teach at the Art Students League of New York in 1932.

Returning to Germany for a short time in October 1932, Grosz observed the growing presence of the Nazi party. Shortly before Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, he permanently moved his family to the United States. In addition to teaching, Grosz contributed illustrations to magazines such as the New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and Esquire. In 1933, he opened a private art school with fellow artist Maurice Sterne, but closed the school in 1937 after receiving a two-year grant from the Guggenheim Museum. Having abandoned satirical drawing, Grosz concentrated on painting oil landscapes. Meanwhile, the Nazis' Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition of 1937 in Berlin featured over 200 of his drawings, many of which were confiscated and later destroyed.

Late Years and Death

Grosz gained American citizenship in 1938, and his fame quickly spread after a 1941 retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Despite his status as a hero of the people in Germany and his critical acclaim in America, Grosz made few sales and was forced to resume teaching at the Arts Students League. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Grosz accepted teaching opportunities at Columbia University, the Skowhegan School of Art, and the Des Moines Art Center, even reopening an art school in his home. Episodes of depression and heavy drinking, which had started shortly after his move to New York, became worse. Feeling as though his efforts resulted in little or no real change, Grosz declared that he was finished with social and political issues, and his style softened to a more sentimental romanticism. However, some of his works from the early 1940s, particularly during World War II, do present an allegorical and dramatic representation of Grosz's moral perspective regarding war. Additionally, some of his last pieces from 1958 were photomontages and hearken back to his earlier Dadaist aesthetic and message, passing judgment upon consumerism and suggesting that his absorption with American culture had ended in disappointment. In 1959, Grosz sold his house and moved back to Berlin. He died shortly after his return, after a fall down the stairs.

The Legacy of George Grosz

His role in the Berlin Dada movement affected political outlooks and artistic developments not only in Germany, but also in Russia, the Balkan nations, and parts of France. Grosz's penetrating, darkly humorous style of drawing and his use of satire as a weapon left a deep impression on the work of his contemporaries and the artists of the next generation. His photomontage work set a standard for social critique in the new medium and inspired the later collages of Romare Bearden. The critical content of his paintings influenced painter Francis Bacon, while his elaborately detailed and unflinchingly honest portraits influenced Lucien Freud's portrait work. Grosz's political orientation and social critique, embodied in his writings, prints, and drawings also had a clear impact on the writings of American novelist John Dos Passos.

Influences and Connections

![Jules Pascin]() Jules Pascin

Jules Pascin![Rudolf Schlichter]() Rudolf Schlichter

Rudolf Schlichter