Healing sea, spiritual and edifying sea, you bleach cardinal, carnivore, cannibal lips, shrimp juice or bicolores and plastered cement of our stripped bathing Eves."

Summary of James Ensor

Although educated in traditional painting, Ensor quickly stepped off that path and began to develop a revolutionary style that reflected his own take on modern life. He was particularly fascinated with the popular carnival culture organized around the celebration of Mardi Gras each year throughout Belgium, most certainly influenced by the fact that his family's shop in Ostend was a main purveyor of carnival paraphernalia. The imagery he produced is consistently cynical and mocking; presenting an almost grotesque form of Realism meant to record the stresses underlying contemporary social morays of his time, and probably of all times.

Accomplishments

- Ensor developed a revolutionary method of painting better suited to his personal agenda. Abandoning the usage of illusionism and one-point perspective to organize the image depicted, he began to build volume with patches of color across the surface of the canvas. The effect was imagery that no longer receded but instead, threatened to enter the viewer's space. Crowded to the point of bursting, denied room to breathe, the figures in Ensor's works impress with their presence.

- The artist was particularly intrigued by the carnival theme and found it an excellent means by which to capture society's foibles. He masked his figures, giving them faces that would express their inner selves rather than their outer, anatomical ones. In this way he was able to dig beneath the surface and reveal the "true face" of society. His exploration of society unmasked eventually caused his rejection by many, even the local avant-garde artists.

- Ensor's social commentary, at first subtle, eventually took on a furiously cynical tone. While it could be noted in the inclusion of a jesting element within an image it could also be a full-blast attack on a subject as sacred as the Entrance of Christ into Jerusalem. There's no question that the artist's continual feeling of rejection was responsible for his frenzied critiques, but the end result was simply further alienation.

Important Art by James Ensor

Portrait of the Painter in a Flowered Hat

Portrait of the Painter in a Flowered Hat represents Ensor in a three-quarter view, openly confronting the viewer's gaze. His use of loose, feathery brushstrokes and the juxtaposition of colored areas on the canvas to suggest volume and the emphasis on differentiating light in order to suggest depth, typify the contemporary portraiture work of the Impressionists who were already painting in Belgium and Holland from the 1870s.

Like many artists before him, Ensor received great inspiration from the tradition of the great masters. This portrait recalls the Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens' Self-Portrait with Hat, (1623-25). Despite the vague similarities between the two images they actually differ quite a bit and there is a clear sense that Ensor is making a joke of the tradition of the old master who he ostensibly emulates. The hat he sports, adorned with pastel flowers and feathers, was part of a traditional Belgian costume worn by women during the mid-lent carnival. And although the facial hair seems close to that of Rubens', he works blue flame-like whiskers into his mustache in a very untraditional manner. Although both depicted figures have an intense expression, suggesting something of their state of mind, Ensor alleviates the unhappy set of his own mouth with the gaiety of the hat.

This painting's light-hearted motifs represent a transition in Ensor's work from his "somber period" to his "light period;" the move from Realism to some form of whimsical reality. It marks the beginning of his experimentation with playful subjects and alternate meanings.

Oil on canvas - Ensor Museum, Ostend, Belgium

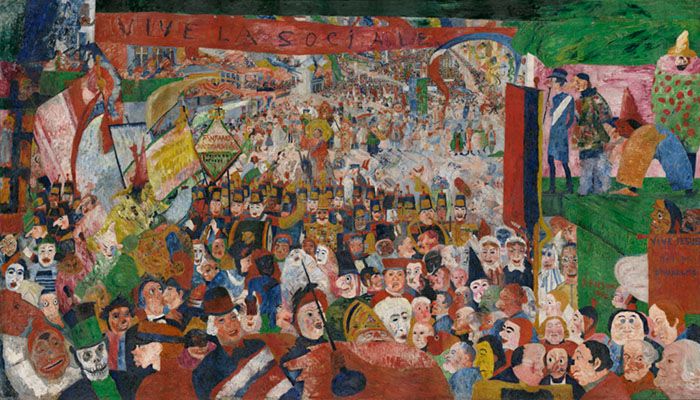

Christ's Entry into Brussels

This painting, no question Ensor's most famous, represents a carnival mob engulfing Christ sitting on a donkey. Although traditional in subject, the presentation is anything but. The formal means by which he describes this chaotic scene defy an easy understanding of what is being depicted. There is a vague sense of a vanishing point perspective. In the foreground, the grotesque faces, painted as if wearing masks, are enormous, and seem to loom in the viewer's face, but as they recede into the background, coming together in a "V," they blur into dots of color. Nevertheless, this is countered by a more modern approach to building volume. Ensor flattens out the figures across the surface of the composition, denying the perspective he's built in order to make the image more pressing and intense. There is even a sense that the crowd is slightly tipped forward, ready to rush out at the viewer and engulf her at any moment. Figures in the crowd are depicted from multiple angles, their shapes and forms deconstructed, and their volume is suggested through the juxtaposition of unmodulated dabs of pure, unsaturated color. This almost primitive, simplistic technique resembles that utilized by Gauguin. As Ensor described: "My colors are purified, they are integral and personal."

Leopold II of Belgium had remade Brussels into a modern city with royal monuments, streamlined facades and broad new boulevards along the model of Haussmann in Paris, but by the late 1880s the country's state of affairs was similar to that of the infamous Paris Commune. The country struggled with economic and political oppression that Ensor captures by transforming Brussels into a sea of disorder and chaos.

Ensor's Christ faces a Belgian public instead of one in Jerusalem. The crowd depicted is a mixture of bourgeoisie, clergy, and the military - basically the ruling class. Individuals are illustrated masked in order to emphasize their superficiality in a carnival-like atmosphere - at the same time as a religious, serious event is supposedly depicted. The strength and intensity of the masses suggest the artist's interest in giving those marginalized by society a voice, enabling them to speak out against figures of authority. This chaotic spectacle takes the focus off the figure of Christ. Christ himself has interestingly been painted with the artist's own features, expressing his empathy with the biblical figure, purposefully representing himself as a martyr.

Ensor found the use of a kind of grotesque realism cleansing and, despite the fact that his representation of the ugly side of society through mystical parody met with harsh criticism; he used this technique throughout his career. In this way his work shares the avant-garde impulse toward social, formal, and libidinal rebellion and anticipates many modern movements from Fauvism to Surrealism, and even Abstract Expressionism.

Oil on canvas - The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California

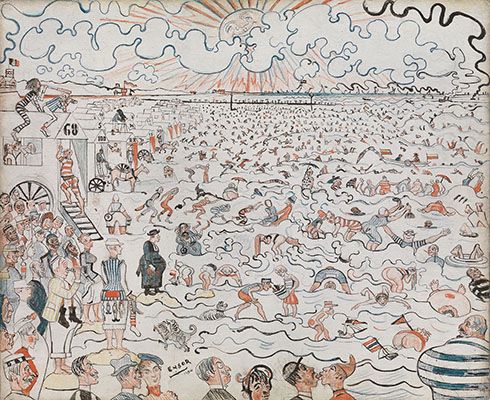

The Baths at Ostend

Here, Ensor draws a whimsical scene, paying homage to his beloved Ostend Sea. By this time the town of Ostend had become a seaside resort, known for its casino, boardwalk, beach, and restorative baths. Ensor uses colored pencils, crayons, and oil to represent this quirky vacation spot. He adds a decorative effect by describing the water and figures with arabesque lines which resolve into a sea of caricatures, drawn on multiple planes, representing the seaside resort as a crowded spectacle. Ensor refrains from using linear perspective and instead, draws his figures across the canvas with a restricted palette of black, blue and red, creating a dream-like space.

In total, Ensor represents this summer playground for the middle-class in a satirical manner. He paints the tourists as caricatures. While overall the scene depicted seems to be a happy one, a sunny day where tourists are enjoying themselves, it also depicts them missing clothing, and a few of which are shown upside down with their heads between their legs- in the midst of vulgar acts. Accordingly, when viewed up close, this painting takes on a somewhat comic and most definitely unsettling effect, it runs counter to the social decorum expected of the bourgeoisie. Ensor's work offers a very clear critique of the contemporary social milieu in which he lived, anticipating movements like Dadaism.

Black crayon, colored pencil and oil on panal - Fondation Challenges, Paris, France

Masks Confronting Death

Masks Confronting Death exemplifies Ensor's usage of masks to reveal the underside of society. Although the instigation for including this prop may have come with his awareness of them in his family's shop, he was most probably attracted to their ability to both hide the specific identity of the figure depicted and simultaneously add a note of intrigue and mystery. In this case the masked figures are even scarier than the figure of Death at the center. In fact, shrouded in a white garment and tucked under a hat, Death seems almost cowering in the face of society's mockery. The appearance of masks within early modern art increased around the turn of the century, as their ability as expressive tools was understood. While Ensor's masks are more mocking in nature, primitive masks were noted in works by Gauguin, Derain, and Picasso.

In this image Death looks out at the viewer, actually confronting her with his gaze.

Ensor was struggling with the recent death of his father at the time the work was created and his inclusion of the motif may indicate his attempt to deal with his own mortality.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

The Vengeance of Hop Frog

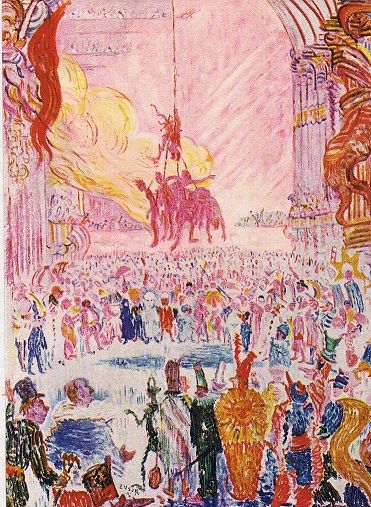

This work represents Edgar Allan Poe's short story, The Vengeance of Hop Frog (1845) wherein the title character, a court-jester, is the victim of social and class injustice inflicted by the king and clergy. Ensor chooses to illustrate the final scene of the story when Hop-Frog exacts his revenge on the king and clergy at a masquerade ball, stringing them up on a chandelier, above the party, and setting them on fire.

Ensor represents a whimsical scene filled with expressive, arabesque lines and pastel colors. Furthermore, the artist uses linear perspective to create a feeling of depth, capturing the enormity of receding space by framing the scene in an arched theatre. Many of the figures are grotesque, broken up in such a way that they appear more abstract concepts of human beings than realistic representations of the same.

Beyond offering a satirical way to highlight the dark side of political and religious figures within modern society, Ensor's representation of Poe's story suggests his frustration at receiving unfair and cruel judgment on the part of contemporary critics. In general, Ensor's dependence on literature as a source of inspiration for his work aligns him with other Symbolist artists at the time like van Gogh and Gauguin.

Oil on canvas - Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

The Temptation of Saint Anthony

Ensor's painting represents Anthony the Great of Egypt (c. 251-356) resisting the temptations of the devil. The monumental painting includes fifty-one sheets of paper, mounted side by side on canvas. It is assumed that the individual drawings, varied in nature but all with acidic color bound by line in a volume-defying style, were part of a book of drawings inspired by Flaubert's narrative. By representing Saint Anthony surrounded by surreal figures, including, a multi-breasted goddess, a sphinx, nude women, bourgeois men, and musical instruments the artist makes a bold statement regarding the depravity of modern society.

Representing Saint Anthony's battle with the devil may have been Ensor's response to the temptations and ethical concerns of modern society. Ensor specialist Susan M. Canning suggests that the symbolism included in the painting, elements such as distortion, exaggeration and the macabre, would have been easily identifiable to the 19th century viewer as indicators of the degeneracy of humanity within modern society.

Colored pencils and scraping, with graphite, charcoal, pastel and water color, selectively fixed, with cut and paste elements on fifty-one sheets of paper, mounted on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

Skeletons Fighting over a Pickled Herring

This painting depicts two skeletal figures fighting over a pickled herring in an amorphous landscape with pastel sky. The sky engulfs the two figures, whose dark tones make them stand out against the background - infusing the work with a lighthearted, comical nature. While the feathery brushstrokes and palette of the sky somewhat recall Impressionism, the fantastic, grotesque subject in a no-man's land actually anticipates much later takes on reality, such as found in Surrealism.

The painting represents the two critics: Édouard Fétis and Max Sulberger. Their negative responses to Ensor's artwork drove him to portray them in multiple satirical paintings. In this particular work Ensor represents himself as a pickled herring being torn apart by their hateful criticism. The word herring in French, hareng-saur-close, if said with the proper pronunciation, apparently sounded like "art Ensor" or "Ensor's art."

Ensor's intention here, as in many of his other works, was clear: "My favorite occupation is to make others famous, to uglify them, to enrich their ugliness." Ensor discovered an iconography of the grotesque that best enabled him to comment on the injustice and superficiality by which he was surrounded. His development of the macabre was part and parcel of his revelation of society's malaise.

Oil on canvas - Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels

Biography of James Ensor

Childhood

James Sidney Ensor was born in Belgium in 1860. His father James Frederic Ensor and mother Maria Catherina Haegheman owned a souvenir shop in the tourist town of Ostend, selling carnival novelties and seaside trinkets. The shop, full of innovative motifs and objects, inspired Ensor throughout his artistic career. He had a happy and carefree upbringing, living with his mother, father, sister and aunt. He went to school at the College Notre-Dame but showed very little interest in learning. He struggled within the structured disciplinary environment and after two years withdrew from school.

Early Training

Ensor showed an aptitude for painting at thirteen and received instruction from two Ostend watercolorists, Michel Thomas Anthony Van Cuyck and Édouard Dubar. As he recounted, "Van Cuyck and Dubar, both pickled and oily, professorially initiated me to the disappointing commonplaces of their dreary, stillborn, and stubborn craft." He enrolled at the Brussels Academy of Fine Arts at the age of seventeen and worked there under the tutelage of Joseph Stallaert, Alexandre Robert and Jef Van Severdonck. Ensor rejected the formal instruction prevalent in the Academy and found creative ways to enliven the mandatory study of antiquity. As he explained: "The moment I arrived, a big problem appeared on the horizon. I was ordered to draw Octavius, the most august of the Caesars, from a white plaster bust. The snowy plaster horrified me. I reproduced it with vibrant pink chicken skin, reddening the hair and causing a great commotion among the students."

Despite causing a scandal, he was allowed to continue his education at the Academy and was permitted to paint from live models. After three years he left the institution, calling the school an "establishment of the short-sighted."

During his years at the Academy, Ensor befriended many other liberal minded artists including Fernand Khnopff, Théo van Rysselberghe, Guillaume Van Strydonck and Theo Hannon. Together they founded the Belgian group of painters, designers and sculptors who would become known as Les Vingt and was responsible for the publication of two artistic journals, La Jeune Belgique and L'Art Moderne. Les Vingt, established in 1883 as an independent artist's group, worked with neither the constraints nor restrictions incumbent to the official Belgian Salon. Other independent artists, such as Georges Seurat, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Vincent Van Gogh, were also invited to include their works among those of Les Vingt.

Ensor exhibited six works at Les Vingt's first show in 1884. Irate critics deplored his paintings and among the negative reactions were comments like "That is painting? No way! It is garbage!" His work was also termed: "Sickening studio rubbish" and "Sinister Idiocies." Although troubled by the reviews, Ensor continued to paint at a steady rate.

Ensor's early career, lasting about five years, is labeled his "somber period" and is characterized as belonging to Realism. Among the subjects of focus were middle-class interiors, self-portraits, and still life paintings, all painted with layers of thick paint in warm colors. Despite the dark interiors, the artist's fascination with the study of light, similar to the Impressionists, is clear. This particular aspect of his painting was considered too revolutionary in Belgium, and accordingly, his works went unsold.

Mature Period

During his "somber period" Ensor painted a work, titled Scandalized Masks (1883), which would lead him in the direction now known as his "light period." Lasting for about fifteen years, this next stage was characterized by the depiction of masks and other carnival paraphernalia. Gradually his work was considered too progressive for Les Vingt and his submissions to the group were rejected. The sculptor Achille Chainaye even requested his official dismissal from the group. This issue was actually put to a vote and although Ensor was able to remain a member, Chainaye resigned. Despite being an outcast in one of the more avant-garde groups of the time, Ensor continued to exhibit with them until they disbanded in 1893.

Ensor's deviant style caused him to become a target of ridicule in Ostend. The rumors about him led his mother and aunt to turn their back on him. He became depressed and his failing art career and the lack of support from his contemporaries drove him to move to Brussels where he sought refuge with the family of Ernest Rousseau, a professor of physics and the Rector of the University of Brussels. It was at Rousseau's house that Ensor befriended Eugene Demolder, who would become one of his biggest supporters, as well as other local intellectuals, artists, and free thinkers. The anarchistic and atheist views of this group served as a major source of inspiration for the artist.

While at the Rousseau's home, Ensor showed off his eccentric personality by assuming the role of the joker, sometimes playing pranks on the family's friends, as well as strangers. Sometimes he went so far as to plagiarize the works of the major masters he studied such as Courbet, Hokusai, De Braekeleer, Rembrandt, Watteau, Bosch, Turner, Manet, and Bonnard.

Ensor returned now and then to Ostend to visit his girlfriend, Augusta Boogaerts, whom he nicknamed "the Siren." She was ten years his junior, had a charming personality and worked at his family's souvenir shop as a salesgirl. Although his parents disapproved of their relationship and they were never to marry, their romance continued throughout his lifetime.

Ensor's circle of friends in Brussels admired his work and wrote enthusiastic reviews of it in local magazines, including la Plume. It is believed that his success as an artist was due to their emphatic critiques. Following great success, he became a founding member of the Free Academy of Belgium in 1901 and was made a "Chevalier" of the Order of Leopold in 1903. While his reputation thrived and his talent came to be admired, his creativity gradually began to dwindle. The decline of the artist's enthusiasm for life can be attributed to any one of the many disappointments he experienced: the loss of his father, his newfound success, and/or the lack of stimulation and encouragement he'd formerly received at the Rousseau's home.

Late Years and Death

Ensor's final period, known as the "crystalline period," began at the turn of the 20th century and lasted fifty years). These works are characterized by vivid colors that scarcely cover the canvas, hesitant lines and the absence of internal structure. While a few were considered innovative and masterful, most were repetitions of earlier paintings and subjects. While he continued to receive official awards - he was admitted to the Royal Academy of Belgium in 1925, made a baron in 1929, presented with the Legion of Honor, had a bust chiseled in his honor by Edmond de Valeriola, and a work of music, James Ensor Suite, composed by Flor Alpaerts - he continued to retreat even further from the public. While his paintings commanded a higher price than any other living Belgian artist, his output dwindled.

Augusta pushed him to continue to work, keeping close track of his paintings, making an inventory of his oeuvre and curating their sale. Ensor was not accustomed to having such an authoritative figure in his life, overseeing his production and the story goes that: "One day, she went out and Ensor left a note on the table 'do not take anything; I have counted everything." On his return she left him a note, "Do not count anything; I have taken everything."

Ensor's death in 1949 caused a spectacle throughout the Belgian community. Cabinet ministers, generals, judges, bishops and artists came to pay their respects. He was buried in the cemetery of Notre-Dame des Dunes, in Mariakerke.

The Legacy of James Ensor

Ensor received a great deal of recognition during his lifetime due to his wedding of technical innovation to social criticism. His explorations, independence from tradition, and purposeful break with reality place him in a category of his own. Aspects of his work were influential in the later formation of a number of significant artistic movements including Symbolism, Fauvism, Expressionism, Dadaism, and Surrealism. For example, his willingness to critique the society in which he lived influenced a range of artists such as Derain, Munch and Picasso, while his use of bold, expressionistic color that adheres to the surface of the canvas and refuses to recede in any traditional manner, affected the works of Matisse, Bonnard, and the German Expressionists.

Influences and Connections

![Honore de Balzac]() Honore de Balzac

Honore de Balzac![Edgar Allan Poe]() Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe

![Emile Verhaeren]() Emile Verhaeren

Emile Verhaeren![Maurice Maeterlinck]() Maurice Maeterlinck

Maurice Maeterlinck