Summary of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity)

Eschewing the idealism and utopianism that marked the first decade of the 20th century and disillusioned by a World War that wreaked havoc on bodies and society, the artists associated with Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity as it is translated in English, presented an unsentimental realism to address contemporary culture. Disgusted with the corruption apparent throughout the Weimar Republic but also entranced by new freedoms, this diverse group of artists did not necessarily share a style but rather a commitment to expose the objective truth underlying contemporary ills. Employing caricature, satire, Neoclassicism, and even Surrealism, artists such as Max Beckmann, George Grosz, Otto Dix, and August Sander portrayed leaders, bureaucrats, bohemians, laborers, and themselves unflinchingly, each complicit in the society they inhabited. The artists highlighted the social and political turmoil of life emphasized through war-profiteers, beggars, and prostitutes. They explored the rise of the metropolis with its freedoms and sexual liberation, but noted the increasing alienation from nature and rural life.

While their version of realism was initially regarded by some art historians as retrograde, Neue Sachlichkeit's variants would go on to later influence Magic Realism and German art of the 1960s as well as contemporary photography as propagated by Bernd and Hilla Becher.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The Neue Sachlichkeit artists embraced realism in defiance of trends towards abstraction but renounced the idiosyncratic subjectivities espoused by early German Expressionists. They instead combined their realism with a healthy dose of the biting protests of the Dada movement. For the most part, their realism was not a traditional mimeticism but a distorted and dark realism that aimed to expose the moral degradation they witnessed in German society.

- While all of the artists were committed to depicting current affairs, their styles ranged from a satirical Verism to a nostalgic Classicism to an uncanny Magical Realism. Despite the stylistic differences, many of the artists preferred more static compositions rather than dynamic ones, rendered their subjects with great precision, and eradicated the traces of the painting process and all gestural elements.

- Portraiture, and self-portraiture, was common among the Neue Sachlichkeit artists. Whichever style the artist practiced, there is usually a tension in the portrait between the individual being represented and the type, or role, that person plays in society. In the effort to paint the truth of the person, Neue Sachlichkeit portraits do not shy away from unflattering details or unsettling psychological effects.

- Neue Sachlichkeit photographers shared the painter's desire to portray the objective truth of reality, but for the most part they avoided the social and political commentary that underlies so much of the painting.

Artworks and Artists of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity)

The Night

In this terrifying scene, Beckmann depicts a chaotic and violent event. Intruders have taken a family hostage, overturned their belongings, and are torturing them. The father hangs from his neck while one of the men twists his arm. Beckmann implies that one of the invaders raped the mother, with her wrists bound and her legs splayed and backside exposed, and a blond-haired child reaches out as another man attempts to carry her out of the room.

Beckmann intensifies the emotional charge of the scene with an illogical composition. For example, the woman seems to occupy the space in the foreground, and yet her hands are bound to a post that appears to be in the background. This distortion of space along with the exaggerated and fractured figures show Bekcmann's debt not only to Cubism but Expressionism as well, making The Night a transitional painting between Expressionism and Neue Sachlichkeit.

Having been supportive of the Great War, Beckmann became disillusioned with war and violence after having served as a medic in the military. Subsequently, he claimed that the role of the artist was to portray the "calamity" of the current situation: "We must be a part of all the misery which is coming. We have to surrender our heart and our nerves....It's the only course of action which might give purpose to our superfluous and selfish existence (as artists) that we give people a picture of their fate."

While Beckmann saw nothing good of the violence that the war had wrought, the scene is not without some ambivalence. As art critic Jonathan Jones argues that the scene "connects itself with images of sex and nocturnal adventure, especially with a scene in William Hogarth's The Rake's Progress, where we see the Rake indulging himself at a house of ill repute in London.". From this perspective, the work echoes a complexity of emotions, combining both "pain and pleasure, torture and desire." Both perpetrators and victims are rendered in the same way, thus in some sense rendering them on equal footing despite the events transpiring.

Oil on canvas - Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Germany

Tingel-Tangel

The painting depicts two bare-chested ladies dancing on a stage, with classical musicians in full tuxedoes playing behind them. Men in suits and official uniforms casually observe the scene. Painted just after the war, Schlichter provides a glimpse into the popular musical cabarets, with their suggestive female performers, that were so popular at the time.

These cabarets were known to be places where drugs and sex were in abundant supply. In normalizing the dancers, likely also prostitutes, the painting acts as a criticism and satirical analysis of society's decadence, a main theme of the New Objectivity movement. Schlichter's use of bright colors, his caricature-like portrayal of the men, and the awkwardness of the women underscore that the Neue Sachlichkeit artists were not interested in meticulously representing the details of what they saw but exposing the underlying truth of the current reality, which they saw as corrupt and bankrupt.

The subject of the cabaret went on to enjoy a life in popular culture, including the 1951 musical Cabaret, and the later film adaptation in 1972 that featured Liza Minelli. These depictions, however, were largely nostalgic and not quite as searing.

Watercolor on paper - Private Collection

Self-Portrait with a Cigarette

One of some 80 portraits painted over his life, here Max Beckmann presents himself in a suit and tie, holding a cigarette, seated before an ochre-colored wall. Perhaps more than the other Neue Sachlichkeit artists, Beckmann probed himself and his inner life in numerous self-portraits. Although he is often known for his "expressionist" language, he rejected the term, the movement, and their artistic ideas altogether. His time as an army medic led to a nervous breakdown, and the misery he witnessed during the war was reflected in his painting style. As critic Edward Sorel explained, "The brutality that they endured or witnessed scarred their psyches and darkened their outlook forever."

During this time, Beckmann frequented the house of Dr. Heinrich Simon, the editor-in-chief of the newspaper Frankfurter Zeitung, and another frequent guest recalled Beckmann during these meetings, "Nothing about him betrayed that he was an artist, but one sensed that in this circle of important men sat one who surpassed them all in concentrated power. His angular head was set on a short neck on his solidly built, athletic body. His face was hard, his profile sharp... not unlike a military inspector... He wore clothes that were too tight and looked like a workman in his Sunday best....His disdain for people was considerable. But under his prickly shell he concealed a highly vulnerable sensitivity, one that he sometimes mockingly exposed." In this particular portrait, Beckman holds a saffron-colored, red polka-dotted scarf on his lap, which references the costume of a clown, a common subject in Beckmann's painting, and thus undermines, or mocks, the dominance he transmitted. Beckmann was not above probing and criticizing his own self as he did other subjects.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Verwundeter (Wounded Soldier)

One of fifty prints in a portfolio titled Der Krieg (The War), Dix portrayed a wounded soldier in combat, surrounded by explosions, in a dark and highly dramatic setting. The character's facial expression suggests agony and suffering, and the overall scene and rendering allude to an imminent death. Dix himself participated in the war as an artillery gunner and faced ferocious battle in Somme and on the Eastern Front, where he was wounded several times. Curator Mark Henshaw describes the print having a "nightmarish, hallucinatory quality" and that "paradoxically, there is also a quality of sensuousness, an almost perverse delight in the rendering of horrific detail." Dix seems to use the printing processes, in which one exposes the metal plate to multiple acid baths, as a metaphor for what happens to human flesh during war.

The prints in Der Krieg all portray the brutality of war and the subsequent social calamity defined by prostitutes, crippled soldiers, and violence, pointing to the ruination and hardening of individuals who experience these cataclysms. Dix certainly had in mind Goya's Disasters of War series (1810-1820), but introduced a more critical and aggressive perspective. Like Goya, Dix strove to depict the objective brutality of the war and its aftermath, but as art historian Matthias Eberle points out, "Dix attacked with a bitter anger only a veteran could feel, the indifference of civilians to the suffering of the war-victims." Dix's publisher circulated the prints among a pacifist organization called Never Again War, but Dix, in his cynical view of humanity, had no illusion that his work might prevent a future war.

Etching, aquatint, drypoint - Collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Child Portrait (Peter in Sicily)

Schrimpf presents a portrait of his son Peter, while in Sicily. The child stands holding onto the balcony railing, while another terrace of the palazzo and green rolling hills appear in the middle and backgrounds. Schrimpf searched for a more poetical type of realism, believing that the calmness and harmony of a timeless approach could counterbalance the turbulent climate of the Weimar Republic. Unlike the Verists, Grosz and Dix, the Classicists of the Neue Sachlichkeit, eschewed satire and caricature for monumental, weighty figures that spoke to a nostalgia for an earlier time.

Despite this desire to flout this unsettled time, Schrimpf combines Classicism with Magic Realism in such a way that this portrait is not without commentary. Dressed in the typical children's fashion of the day, the young boy stands with a puzzled, even reserved expression on his face. Schrimpf and other Neue Sachlichkeit artists insisted on the unsentimental portrayal of all their subjects, even children. While we often think of children's innocence, their wonder at the world, and their sense of play, Schrimpf's portrayal suggests something more sinister, more foreboding, more alienating - a mood we would expect with the portrayal of disillusioned adults. The child's outsized proportion to his surrounding also adds a surrealistic quality to the composition that is rather disconcerting. Schrimpf was profoundly influenced by his countless visits to Italy and was a great admirer of Renaissance art, but it was the Pittura metafisica (metaphysical art) of Carlo Carrà and Giorgio de Chirico that had the greatest impact on Schrimpf's Magic Realism and naïve style.

Oil on canvas - Los Angeles County Museum of Art

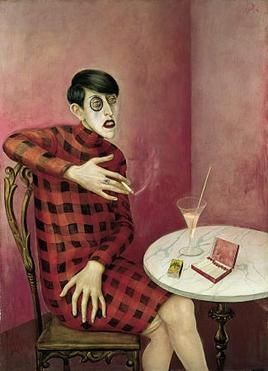

Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden

During the Weimar Republic, a new type of woman emerged. She wore bobbed hair, smoked cigarettes, and drank cocktails. She was sexually liberated and career oriented. The "New Woman" was androgynous and bohemian, and she was the source of much anxiety among male artists, writers, and intellectuals. In some ways, Dix glorifies the journalist and poet Sylvia von Harden as the embodiment of the New Woman, but as with all of Dix portraits, he did not strive to make her beautiful. As one art historian describes, "Dix stripped his sitters of all pretenses and staged their subjecthood as either victim or prop of social construction," and here Dix subtly pulls back the curtain on the New Woman.

While all of the attributes of the New Woman are present - the haircut, the cigarette, the cocktail - Dix distorts the figure to call attention to her seeming lack of feminine attributes. Her hands are oversized, and while their placement recalls the pose of the Venus de Milo, with one hand covering the breasts and the other her pudendum, here, von Harden's geometric dress completely flattens her breasts, nullifying the need for cover. Additionally, the placement of her left hand actually leads one's eye to the sitter's knees, and one sees a strikingly realistic detail: the stocking on her right leg has rolled down below her hem line, exposing her pale flesh. Such unkemptness, or lack of decorum in a public space, subverts respectable femininity. Some have even gone so far as to suggest that her overly long and cylindrical neck is rather machinelike. Overall, the harshness of her facial features, the flattening of her figure, the mechanizing of her body - all contrasted with the ornate curves of the chair in which she sits - presents an ambivalent view of Dix's friend and the new stereotype.

Mixed media on wood - Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

Flat Irons for Shoe Manufacture, Fagus Factory I

The work pictures flat irons, used in shoe manufacturing, organized in a very orderly and systematic way. It is exemplary of Albert Renger-Patzsch's body of work that aimed to capture the "reality" of ordinary objects. This fascination with the beauty of the commonplace granted him the title of "photographer of things." In 1927, Renger-Patzsch wrote, "We still don't sufficiently appreciate the opportunity to capture the magic of material things. The structure of wood, stone, and metal can be shown with a perfection beyond the means of painting....To do justice to modern technology's rigid linear structure...only photography is capable of that." These sharp, objective, and realistic depictions of life made him a key artist of the New Objectivity movement.

The sense of order was one of Renger-Patzsch's main themes, and the way in which he captures the objects' matter-of-factness lends an air of scientific illustration to the photograph. It should be noted that in his striving for "the truth" Renger-Patzsch's photographs seem to be impartial, without judgment or critique, an attribute completely lacking among his painter colleagues.

While his 1928 book of photographs entitled Die Welt ist schön (The World is Beautiful), a title forced on him by his publisher, was extremely popular and is a precursor to the industrial photographs of Bernd and Hilla Becher that came a few decades later, he remained largely unknown in the United States at the time.

Gelatin silver print - The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Eclipse of the Sun

In Eclipse of the Sun, Grosz critiques the power and greed of the military industrial complex that grew after World War I. He depicts the war-hero-turned-German-president Paul von Hindenburg whispering into the ear of a military-leader-turned-industrialist while besuited bureaucrats, without heads, furiously agree to and sign off on their desires. In the upper left corner, the sun has been eclipsed by a dollar sign. Art historian Matthias Eberle argues that the squints of the men in charge make it seem like they "cannot see past the end of their nose," and the headlessness of the bureaucrats suggest their mindless, unthinking acceptance. A donkey with blinders stands atop the table representing the bourgeoisie, blinded to what is transpiring in the upper echelons of their government, and to the right of a table, a young person behind bars might represent the future children the leaders have no apparent thought for or a dissident voice. Ominously, a skeleton lurks in the bottom right corner.

The satirical and metaphorical nature of this work is exemplary of Grosz' painting output. His unique artistic language of cartoon-like caricature employs irony, humor, and exaggeration in order to expose and ridicule the underlying conflicts that plagued Weimar society. Art critic Michael Kimmelman boldly stated, "More than any other artist since Daumier, Grosz captured through caricature the political spirit of a particular moment, and his vision of Germany between the world wars has lost none of its power to startle or frighten."

Oil on canvas - Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, New York

Self-portrait

A man in a translucent shirt sits on a covered bed next to a reclining, nude woman, whose hand grazes her hip and who looks straight ahead of her, outside of the canvas. Behind them, a diaphanous curtain separates the couple from a skyline in the twilight. The self-consciously posed figures - the man is Schad's self-portrait - the plethora of symbols, and the mysterious mood of the painting do not add up to a moment of sensuousness but belie a coldness and suggest something more allegorical.

Schad, who averts his eyes from the viewer, wears a translucent shirt, covering and exposing himself simultaneously. The shirt might be a reference to the Italian paintings he studied in Italy in the first half of the 1920s. The woman, perhaps an embodiment of the bohemian "New Woman" and/or a prostitute, is severe, with angular features and a bobbed haircut. Heavily make-upped, she bears a long scar down her chin, likely inflicted by a man who was adamant about marking his property and warning off other suitors. She wears a ribbon around her wrist, and one can see the cuff of her red, silk stocking, just over Schad's right shoulder. Rather mysteriously, a narcissus flower appears behind her, the lip of the vase barely visible above her breast. The flower, pointed toward the artist, alludes to the Greek myth of Narcissus who drowned while trying to embrace his own reflection in a pool of water. Art historian Linda Nochlin claims that the painting is a "a haunting image that - partly because of the picture surface's seductive smoothness and partly due to the subject matter's dreamlike perversity - persists in the mind's eye long after the actual experience of viewing the painting."

Although his early works show a clear influence of Cubism and Futurism, Schad developed his iconic realistic language during his stay in Italy, where he was especially influenced by Raphael. Turning his back on Expressionism and abstraction, he developed his own language that was associated with both the Classicist and Magic Realist branches of Neue Sachlichkeit.

Oil on Wood - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Coal Carrier, Berlin

A man with stubble on his chin and wearing dirty, worn pants and jacket steps up and out of a darkened doorway carrying a basket full of coal from the bowels of a building.

Along with Albert Renger-Patzsch, August Sander was one of the most influential photographers associated with the Neue Sachlichkeit group. He did not portray the beauty of industrial objects but instead aimed to portray the reality of ordinary life in the Weimar Republic at the time. As he said, "Nothing is more hateful to me than photography sugar-coated with gimmicks, poses and false effects. Therefore, let me speak the truth in all honesty about our age and the people of our age."

This photograph was part of his book entitled the Face of our Time published in 1929, which contained a selection of 60 of his portraits from a larger series entitled People of the 20th Century. Sander organized the portraits into categories: farmers, tradesman, woman, classes and professions, artists, city and "the last people," which portrayed homeless men and women along with war veterans. Critic Laura Cumming writes of these portraits, "Each person presents him or herself with more or less gravity to be fixed in black and white forever, and each is bared in that moment - giving themselves away." Sander's portraits not only document the types of workers and various classes but capture an array of emotions that all people, no matter their status, experience.

Sander worked in large formats and in slow exposures, sometimes over three seconds long, in order to capture the slightest details of his subjects. Sometimes recorded in the subject's work environment and sometimes created in the studio, these portraits portray the complex variety of Germany society. Cumming adds, "It's rightly said that some of Sander's photographs are as historically detailed as a passage of Zola. Together they amount to a journey through German society in a disastrous era."

Gelatin silver print - J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Beginnings of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity)

Before World War I, Expressionism, as practiced by the groups Der Blaue Reiter and Die Brücke, held sway in Germany. Inspired by the exoticism of non-Western art and the dynamism of modern, urban life, these artists abandoned the traditional conceptions of art and searched for a language that was highly intuitive and emotional. Artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emile Nolde focused on the individual's inner world, highlighting the subjective perspective of seeing and understanding the world. If the idealism of Expressionism reigned before World War I, Dadaism, founded in 1916 in Zurich and spreading to Berlin shortly thereafter, embodied the nihilism and anti-art sentiments felt by many artists during the war. The fierce critique of war and bourgeois culture led to the rise of the photomontages of Hannah Hoch and Raoul Hausmann after the war.

In the wake of the establishment of the Weimar Republic, Germany's first democratic government, and still reeling from the devastations of World War I, social upheaval, and economic distress, in November 1918 Expressionist painters Max Pechstein and César Klein formed an artistic group in order to foster much-needed unity between artists, the public, and the state. As art critic Edward Sorel explained, the November Group "were confident that merely by rejecting the sentimentality of prewar German Expressionism, and substituting a more realistic, sober view of the life around them, they could not only bring about a new society, but usher in a 'new man.'" With the radical aim of establishing and supporting a socialist society, the stylistically diverse group of over 100 artists, which included Höch, Hausmann, Otto Dix, and George Grosz, held many exhibitions throughout the 1920s and encouraged the development of a new type of realism that came to be known as Neue Sachlichkeit.

A New Realism: Neue Sachlichkeit

By 1922, the painters Otto Dix and George Grosz were among those who stood out among German artists practicing the new realism. Having both participated in the beginnings of German Dadaism, each moved away from the conceptualism promoted by the Dadaists in favor of hard-hitting realism that exposed the effects of war and corruption. The German artist Käthe Kollwitz, usually associated with a version of Expressionism, was another contemporary that engaged the horrors of war and explored the humanity of the working class, but her treatment of her subjects had a compassion and mournfulness that was absent among the younger, brasher painters.

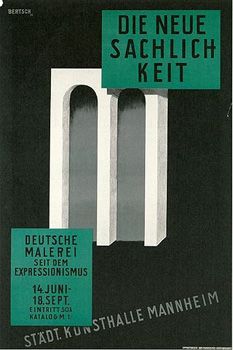

The term Neue Sachlichkeit, which is often translated as New Objectivity, was first coined by Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, the director of the Kunsthalle in Mannheim, as the title for an art exhibition that was initially planned to open in 1923 but did not open until 1925. The exhibition surveyed the post-Expressionism work of various artists, including works of George Grosz, Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, Georg Schrimpf, Alexander Kanoldt, and Carlo Mense, among others. While varied stylistic approaches were still apparent, all of the artists focused on an objective view of life aimed at portraying a more "tangible reality." Another translation of Sachlichkeit is often "matter-of-factness," suggesting the focus on the commonplace and straightforward.

Hartlaub acknowledged the contradictions within the group, noting that the movement expressed "the enthusiasm for immediate reality as a result of a desire to take things entirely objectively, on a material basis, without investing them with ideal implications" and, yet, some tended toward a "cynicism and resignation." Given this spectrum, paintings labeled as "New Objectivity" can be hyper-realistic portraits of children or scathing caricatures of corrupt individuals.

The rejection of romantic and idealistic longings was well received among Weimar's intellectuals, who promoted a more "conscious" society. Hartlaub's exhibition travelled through several cities in Saxony and Thuringia, making Neue Sachlichkeit quite popular and influential. Although the second half of the decade saw the continued development of New Objectivity, the 1925 exhibition was the only contemporary public showcase associated with the movement.

An "Objective" Understanding

Germany suffered numerous casualties during World War I, and approximately a quarter of a million people died from starvation or disease in the months that followed the conclusion of the war, leaving the nation in utter devastation. Combined with a highly unstable social, economical, and political context, this led to the emergence of a socialist revolution that resulted in the establishment of the Weimar Republic in 1919.

Germany's first democracy aimed to reinvigorate and redefine the nation with a new political and economical approach; however, in the years that followed, life in the Weimar Republic was marked by a tremendous hyperinflation, especially between 1921 and 1923, making the value of the German Mark completely worthless. This economic distress defined a continued generalized climate of starvation and disease, where prostitutes, beggars, and overall degradation was predominant across the nation. With huge amounts of debts to pay, the country's situation did not seem optimistic.

While geographically dispersed across Germany and stylistically diverse, the Neue Sachlichkeit artists shared the same skeptical perception regarding Germany's direction. Deeply disillusioned, their subjects and themes echoed their concerns. Otto Dix explained that all the artists "wanted to see things quite naked, clearly, almost without art."

Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity): Concepts, Styles, and Trends

The Verists

In 1922, Gustav Hartlaub had already identified two dominant approaches among the Neue Sachlichkeit artists, writing, "I see a right wing and a left wing. The former conservative to classicist... the other, left wing, harshly contemporary... the true face of our time." The left wing of the group, including Grosz and Dix, came to be called the Verists, from the Latin word Verus meaning "true," and defined a form of realism that preferred contemporary subjects with an underlying political commentary. Art historian Stefanie Gommel writes of the Verists, "In paintings that were partly caricatured exaggerations and partly shocking, their cool, razor-sharp perspectives nailed their era and the miseries of conditions during the Weimar Republic." They were unified by their aggressive, bitter, and highly critical attacks on society and power, focused on the effects of World War I and its economic impact on individuals. Developing the ongoing conception led by Dadaism that art didn't have to adhere to specific rules or languages, the Verists developed a form of "satirical hyperrealism," a term employed by Raoul Hausmann, that emphasized the ugly and the raw in a provocative way.

Other painters of the group included Conrad Felixmüller in Dresden, Rudolf Schlichter, and Christian Schad in Berlin, whose creations were so sharp they "cut beneath the skin," according to art critic Wieland Schmied, the early works of Max Beckmann, along with, Karl Hubbuch, Georg Scholz, and Wilhelm Schnarrenberger in Karlsruhe. The Verist branch also included some photographers. While primarily known as a Dadaist for his sharp criticality of Weimar Germany, John Heartfield's photomontages are an important example of this Verist trend.

The Classicists

Hartlaub's right wing, the Interwar Classicists, rooted themselves in the classical conception of art, searching for a more universal artistic language and proclaiming a "return to order" that was common during the interwar years throughout Europe. The group drew inspiration from the Italian metaphysical painters such as Carlo Carrà and Giorgio de Chirico. They developed a language that was often described as "cold" and "static" and mostly avoided the social issues that were so central to the Verists. The classicists were mainly defined by the works of Georg Schrimpf, Alexander Kanoldt, Carlo Mense, Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, and Wilhelm Heise.

Magic Realism

In 1925 the art critic Franz Roh coined the term Magic Realism to describe the trend of Neue Sachlichkeit, but during the development of the style, the term came to describe a different stylistic approach that combined an "objective" idea of life with surreal or mysterious qualities. Overall, these works emphasized a profound technical accuracy mixed with an elusive "magical" element that seemed to grant the work a "fantastic" perspective. During this time, the works of Albert Carel Willink are a main example, especially for his use of foreign objects in architectural contexts. Other artists include the later works of Max Beckmann, Carl Hofer, and Franz Radziwill, one of its main contributors whose complex, surrealistic art was created away from the artistic centers in the coastal city of Dangast. Radziwill, like Willink, used a combination of estranged elements within reality, aiming to depict "objectivity" through a different perspective.

The term Magical Realism migrated to North and South America and came to be associated with the uncanny and realist paintings of American artists Paul Cadmus, George Tooker, and sometimes Andrew Wyeth. Mexican artists such as Frida Kahlo were also engaged a Magical Realist style. It is perhaps most often associated with the literary genre, most popular in Latin America, that was practiced by the legendary writers Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Isabelle Allende, and later the term was applied to films such as Like Water for Chocolate (1992) and the films of Terry Gilliam.

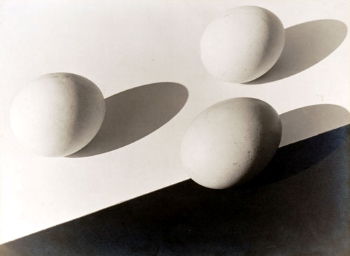

New Objectivity Photography

Photographers also aimed to accentuate an objective viewpoint, bringing in an unprecedented documentary aesthetic to the medium. The artists preferred subjects that depicted industry, technology, architectural spaces, and ordinary objects from daily life, such as eggs and plants. Like some of the painters, the photographers also took a keen interest in portraiture in an effort to document the realities of everyday people. In their main concern with portraying reality objectively, they tended to be associated with the Verists. Their works are characterized by the use of sharp angles, impartial perspectives, visual clarity, and order. Macro photographs were also predominant, especially in nature photography, and they often relied on serialized repetitions and ordered arrangements of objects to portray the industrial life.

Albert Renger-Patzsch's work is mostly characterized by industrial scenes and close-ups of nature, whereas August Sander, one of the most acclaimed of Germany's photographers, was known for his portraits. Hein Gorny, whose work was industrial and commercial, drawing on the tendencies spread by the Bauhaus and the Deutscher Werkbund, was also associated with the movement. Karl Blossfeldt's plant photography is also seen to be a fundamental example of the movement.

Later Developments - After Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity)

Neue Sachlichkeit came to an end with the rise of the Nazis and the end of the Weimar Republic in 1933. In October 1933, Wilhelm Frick, the Reich Minister of Interior, demanded "an end to the spirit of subversion" in art, adding that the "completely un-German constructs carrying on under the name of New Objectivity must come to an end." In 1937 all the group's work had been banished as a result of the Nazis campaign to clear Germany of "degenerate art," in German entartete kunst, which did not conform to the Nazi worldview and included all Modern art in general. Degenerate art was forbidden to be exhibited (except in an infamous exhibition put on by the Nazis to clarify public opinion), sold, and, in some cases, artists were forbidden to create. Some of the movement's artists, such as Max Beckman and George Grosz, fled the country, while others remained and adjusted to the new oppressive lifestyle.

Given the art historical tendency to favor the conceptualism unleashed by Dadaism, Neue Sachlichkeit fell out of favor with critics and historians, and its lack of a unified style and approach led some to dismiss the movement as secondary. Despite these attitudes, a new appreciation for New Objectivity as a movement began in the 1960s. This was mainly derived from Photorealism and Critical Realism movements that found great inspiration in New Objectivity. The movement thus experienced a "revival" in Germany, influencing important artists such as Sigmar Polke and his Capitalist realism ideas.

It can also be seen to be a main influence in the works of contemporary realistic photographers, such as the German husband and wife photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher, founders of the Düsseldorf School, who taught Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Thomas Ruff, and Thomas Struth.

Useful Resources on Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity)

- New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic 1919-1933Our PickBy Stephanie Barron and Sabine Eckmann (editors) / 2015

- German Post-Expressionism: The Art of the Great Disorder, 1918-1924By Dennis Crocket

- New ObjectivityOur PickBy Sergiusz Michalski / 1978

- Neue Sachlichkeit and German Realism of the Twenties.Our PickBy Wieland Schmied / 1994

- World War I and the Weimar Artists: Dix, Grosz, Beckmann, SchlemmerOur PickBy Matthias Eberle

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI