Summary of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, the Baroness as she was known, became a living legend in the bohemian enclave of New York City's Greenwich Village in the years before and after World War I. A provocateur and essential catalyst for New York's burgeoning Dada movement, the Baroness obliterated the boundaries of conventional norms of womanhood and femininity and upended notions of what was considered art.

Along with the infamous French artist Marcel Duchamp, she pioneered the use of the readymade, and she stretched and manipulated the English language to create avant-garde poetry. Her penchant for cross-dressing and incorporating found objects into her wardrobe made going out in public a daily Dada performance. The Baroness was a radical proto-feminist who critiqued patriarchal norms but was largely overshadowed by her male colleagues. Her daringness was largely ascribed to female eccentricity, and she became a footnote in the annals of New York Dada. It has only been recently that her contributions to the avant-garde have been recognized for their innovativeness.

Accomplishments

- Steeped in avant-garde principles and strategies, Freytag-Loringhoven's work questions the very nature of what society considers art. The Baroness' use of the "readymade", a found object presented as a work of art, demands that the viewer consider the divide between high and low culture, utilitarian, everyday objects and fine art, and the role of the artist not as original creator but as appropriator. Her readymades and assemblages disrupt standard notions of beauty. Furthermore, the ephemeral nature of so much of the Baroness' work deeply embodies Dada's lacerating critique of the commodification of art objects, perhaps more so than Duchamp's "readymades," which were embraced by the very institutions they meant to undermind.

- The Baroness took the idea of the "New Woman," the image of the independent modern woman popularized at the end of the 19th century, to new heights with her rabid insistence on intellectual, artistic, and sexual autonomy. Her eccentric dress and unapologetic use of her body, both as a model and a performance artist, set her apart from her male Dada colleagues.

Important Art by Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

Enduring Ornament

Enduring Ornament is the Baroness' earliest known objet trouvé (found object). Said to have been found on her way to marry the Baron Leo von Freytag-Loringhoven at City Hall in New York City, the work is a simple, rusted iron ring, an auspicious find on the way to one's nuptials. Measuring about 3 ½ inches in diameter, however, the ring does not actually function as a wedding ring, but the Baroness saw in its roundness a female symbol. As historian Irene Gammel wrote, the title of the work "suggests a symbolic connection with her marriage (although the artwork would prove much more enduring than the marriage itself )." The Baron returned to Germany just prior to World War I, where he took his own life.

Freytag-Loringhoven discovered the ring and anointed it a piece of art in 1913, one year before Marcel Duchamp would present his Bottle Rack, known as the first "readymade." The readymade is an ordinary object, often industrial in nature, which the artist selects and sometimes modifies, designating it art. This strategy calls into question long-held tenets about the originality of the artist and the uniqueness of the art object.

Despite the similarity in artistic strategy, a major difference between Duchamp's and Freytag-Loringhoven's work lies in the lives of their objects. Whereas Duchamp's readymades were made with a nod to the exchange of objects and money in the art world, Freytag-Loringhoven's circulated among other channels. As art historian Amelia Jones writes, the "Baroness's readymade and assembled objects either self-destructed or very slowly percolated out into the world. " Enduring Ornament was one of four objects that the Baroness gave to friends Pavel Tchelitchew and Allen Tanner while living in Berlin in the 1920s and only it resurfaced eight decades later.

Rusted metal ring - Private Collection

God

The readymade sculpture God epitomizes the spirit and avant-garde strategies of New York Dada. Made in the same year as Duchamp's famous Fountain, a urinal turned on its side, God consists of a cast iron drain trap set on its end, mounted on a miter box. Freytag-Loringhoven elevates the everyday and industrial to art and asks us to question the use-value and aesthetic-value of art. God shows a Dadaist irreverence toward the authority of a higher power, substituting the holy image with that of lowly plumbing materials. Duchamp once observed that "The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges ." Along with Duchamp's Fountain, God gives an ironic nod to Duchamp's declaration. The sculpture, a pipe that no longer functions as it should, also suggests a twisted phallus, perhaps the Baroness' critique of a male-dominated, phallocentric society.

Just as Duchamp's championing of the readymade eclipsed the Baroness' first use of it, God was, until recently, attributed to Morton Schamberg, an artist known for his photographs of abstracted machine imagery. The attribution is likely from the fact that the Baroness ripped out the clogged pipe in Schamberg's studio and attached it (perhaps with Schamberg's assistance) to the miter box, at which time Schamberg photographed it in his studio.

Plumbing trap mounted on miter box - The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Cathedral

Made during her years in New York City, Freytag-Loringhoven's Cathedral, a piece of found, fractured wood with irregular, elongated lines, mounted simply on a piece of scrap construction wood, suggests the outline of the city's distinctive skyscrapers. Replacing the sleek lines and materials with jagged wood, Cathedral offers an organic riposte to the rationalism of the steel and glass skyscrapers that were beginning to rise around the city. One of the early skyscrapers, the Woolworth Building, finished in 1912, was known at the time as the "Cathedral of Commerce." With this suggestively titled readymade, the Baroness offers a critique of the capitalist society that worshipped the god of commerce over all else.

Art historian Irene Gammel suggests that Cathedral is also analogous to the Baroness's bodily performances in the public spaces of urban New York, writing, "the Baroness proudly displayed her weathered and erotic body - and conceptualized New York City in the upright dignity and weathered stateliness of her Cathedral. Both precariously aging bodies tell the tale of braving the elements - a tale of quotidian survival." Having spent most of her life in abject poverty, the Baroness was said to have acquired a rather haggard appearance early on in life but, refusing to accept normative standards of beauty and sexuality, continued to use her body as an expressive and disruptive force.

Wood fragment, 10 7/16 in. - The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Portrait of Marcel Duchamp

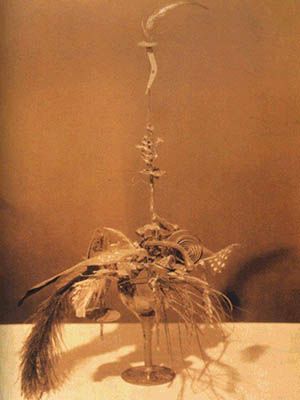

"Her best-known sculptures look like cocktails and the underside of toilets," art critic Alan Moore wrote of the Baroness' body of work. Portrait of Marcel Duchamp in effect serves up the artist as if a cocktail, adorned with feathers and precariously presented as if a delicate, rare bird. In this abstract portrait, Freytag-Loringhoven does not attempt to present a likeness of the artist, the target for her unrequited love, but instead presents an assemblage of found feathers and other detritus to hint at Duchamp's essential nature. Initially, the Baroness had intended the sculpture as a trophy to give to Duchamp for "The Most Inventive Artist." It is possible, though, that the Baroness was subtly poking fun at Duchamp. She wrote to Jane Heap, one of the editors of The Little Review, "cheap bluff giggle frivolity that is what Marcel now can only give. What does he care about 'art'? He is it."

No longer extant, this photograph by Charles Sheeler provides the only documentation of the sculpture. While Duchamp did not return the Baroness' romantic advances, the anti-mimetic portrait suggests an ongoing collaboration and dialogue between the two artists. An earlier, painted portrait of Duchamp with two of his readymades, as well as the artists' collaboration for The Baroness Elsa Shaves Her Pubic Hair, show just how connected the artists were in their lives and work. However, until the recent interventions of feminist art historians, Freytag-Loringhoven had more often been regarded as a muse than as Duchamp's equal.

Assemblage of miscellaneous objects in a wine glass

Limbswish

Freytag-Loringhoven's sculpture Limbswish exemplifies the artist's practice of incorporating found objects into her everyday dress, thus collapsing the distinction between life and art. The curtain tassel which hangs within the core of Limbswish's metal spiral was sometimes worn at the hip by the Baroness as she paraded about in the streets. The title of the work is itself a poetic pun referring to the movement it made when worn as an adornment (limb/swish, limbs/wish). The object was itself a kind of performer, making a distinctive sound as the Baroness walked.

Limbswish demonstrates the artist's interest in making kinetic objects that have a corporeal component. Even when mounted to a wooden base, Limbswish appears bouncy, the coiled spring dangling like an earring. As Irene Gammel suggests, the work may also subtly refer to the Baroness's own gender transgressions, as the term "swishes" was used to describe some gay men who publicly referred to themselves as "fairies." Against the backdrop of the "boys' club" of Dada, Freytag-Loringhoven's unabashed sexual references and unapologetic bodily presence countered gender norms. Works such as Limbswish assert that a woman could be provocative rather than passive. Amelia Jones, in her book Irrational Modernism: A Neurasthenic History of New York Dada, argues that it is with the Baroness' provocations that we may find the limit to the progressiveness of Dada. Frequently described by her male peers as repulsive and threatening, "she also functioned as a site of violent projections. She was thus a figure who pointed to the limits of avant-gardism as such."

Metal spring and curtain tassel - Private Collection

Dada Portrait of Berenice Abbott

The photographer Berenice Abbott, the subject of Freytag-Loringhoven's 1923-26 portrait, was a lifelong friend and supporter of the Baroness. Abbott met Freytag-Loringhoven in New York in 1919 and was taken with the artist's performative transgressions. Abbott said of her friend, "she invented and introduced trousers with pictures and ornaments painted on them. This was an absolute outrage... Elsa possessed a wonderful figure, statuesque and boyishly lean. I remember her wonderful stride, as she walk[ed] up the street toward my house." Freytag-Loringhoven's portrait of Abbott is resplendent with myriad materials and textures.

Rich with references to Abbott's appearance and life, Freytag-Loringhoven's portrait captures her close personal relationship with Abbott. Freytag-Loringhoven's dog - who purportedly had a particular fondness toward Abbott - is pictured in the bottom of the canvas and a handlebar mustache on Abbott's face serves to represent her androgyny. The portrait showers Abbott's image with adornments, including a brush with a white stone, a brooch, and gold-encrusted eyelashes. Not only does Freytag-Loringhoven's portrait bespeak the artist's intimate knowledge of Abbott, but it is also an innovative example of mixed media collage. Building on Synthetic Cubism, the sheer number and complexity of materials used is unusual for its time and looks forward to the painting practices of the later 20th century.

Gouache, metallic paint, and tinted lacquer with varnish, metal foil, celluloid, fiberglass, glass beads, metal objects, cut-and-pasted painted paper, gesso, and cloth on paperboard - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Biography of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

Childhood

Born Elsa Hildegard Ploetz to a middle-class family in 1874, Elsa was the elder of two siblings. She was not born a "Baroness," as she would later come to be known, but acquired the name von Freytag-Loringhoven when she married. She characterized her younger sister, Charlotte Louise, as the relatively more "sensible" person, unlike her mother Ida-Marie Ploetz, with whom she more readily identified. Freytag-Loringhoven described her mother as having a "sweetness and intensity - passionate temperament - only softer as I - kept subdued - regulated by custom-convention ." Ida-Marie died of uterine cancer in February of 1893, when Freytag-Loringhoven was just nineteen. Ida-Marie had suffered for years with mental illness and had spent two years prior at a sanatorium in Stettin, Germany. Shortly after her mother's death, which Freytag-Loringhoven blamed on her father, Freytag-Loringhoven had a violent encounter with her father, who had a history of abusive treatment of his daughter. "My father... behaved so unspeakably, pitifully ridiculous that I felt an overpowering nausea," Freytag-Loringhoven wrote of the attack. Her father's remarriage three months after her mother's death and his continued ill treatment of her, led Freytag-Loringhoven to run away to Berlin to live with a favored aunt.

Berlin was highly influential for Freytag-Loringhoven's future as an artist and as a provocateur. There she met the young Freytag-Loringhoven was exposed to bohemian theatre, art, and poetry circles. She encountered vaudeville, and having little money to support herself, she worked both as a chorus girl at Berlin's Zentral Theatre and as a waitress during these formative years. In that city she would also explore her bisexuality and gender fluidity, modeling for Henry De Vry's erotic series "Living Pictures " and starting a relationship with the cross-dressing graphic artist Melchior Lechter. Freytag-Loringhoven would spend much of her life living precariously, following the travels of artists with whom she made artistic as well as romantic connections.

Early Training and Work

Freytag-Loringhoven next moved to Munich, where she began to take lessons at an artists' colony. In Munich she met the Jugendstil architect August Endell, whom she married in 1901. In 1903, however, she left Endell for his friend the translator Felix Paul Greve. The couple then traveled to Naples, Zürich, and back to Berlin.

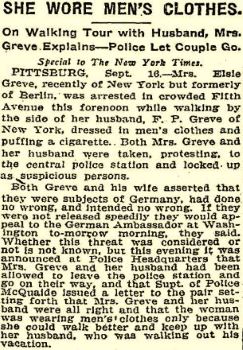

For what Freytag-Loringhoven lacked in academic training, she made up for in experience and in audacity. Greve found himself in severe debt, and Freytag-Loringhoven helped him to stage his suicide. Following Greve's "death" in 1909, Freytag-Loringhoven followed Greve to the United States, first landing in Pittsburgh and then moving to Kentucky and running a small farm. After a year, Greve left her and moved to Canada. Left in Kentucky, with limited knowledge of English, Freytag-Loringhoven began traveling through Virginia and Ohio, modeling for many artists and photographers along the way. Most notably, she posed for the photographers George Biddle and Charles Sheeler in Philadelphia.

Freytag-Loringhoven made her way to New York, where she met and married the German Baron Leo von Freytag-Loringhoven in 1913, thus endowing her with the title of "baroness." Their romance would be short-lived, however, as Leo returned to Germany on the eve of World War I, where he ultimately committed suicide after being held as a prisoner of war. After Leo's death, Freytag-Loringhoven had to make money and began modeling at the anarchist Ferrer Center and the Art Students League, where she met several influential artists, including the Dada and Surrealist photographer Man Ray, but thoughout this period, she largely lived in poverty.

New York Dada

Freytag-Loringhoven's years in New York would irreversibly shape the direction of her artistic career. In the early 1910s, she began to make sculptures out of found and discarded objects, anticipating a tactic which would later become a staple of the Dada movement. Emerging in the wake of World War I, Dada challenged societal norms and rational thought so prized by the bourgeoisie and sought to change the definition of art. Freytag-Loringhoven created collages,assemblages, paintings, and sculptures out of rubbish found on the streets. Her first known objet trouvé (found object) was a rusty metal ring which she titled Enduring Ornament in 1913. Freytag-Loringhoven and other Dada artists, especially her colleague Marcel Duchamp, began to defy the notion that art must be crafted by a singular author as well as the idea that it must conform to established notions of beauty.

Freytag-Loringhoven and Duchamp began to select everyday, often utilitarian, objects, designating them art; Duchamp would come to call such sculptures "readymades." Freytag-Loringhoven's irreverent sculpture God (1917) is the artist's most well-known readymade, which she made by mounting a found plumbing trap to a mitre box. God was made in the same year Marcel Duchamp's infamous Fountain, a urinal which Duchamp submitted to the American Society of Independent Artists Exhibition. Some art historians speculate that, in fact, the Baroness was the mastermind behind the groundbreaking conceptual work of art, citing a letter that Duchamp wrote to his sister recounting that "one of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture." The urinal's inscription of "R. Mutt"-a homonym for Armut in German, meaning "poverty"-would certainly have been a pun that the Baronnes relished.

Freytag-Loringhoven admired Duchamp both artistically and perhaps romantically. One of her early performances consisted of her rubbing a newspaper article about the artist's famous painting Nude Descending a Staircase (1912) over her naked body and then reciting a poem that ended, "Marcel, Marcel, I love you like Hell, Marcel." While Duchamp did not return her romantic advances, he did return the admiration for her as an artist, saying, "She's not a futurist. She is the future." Some historians suggest that the Baroness's persona and physical appearance inspired Duchamp to adopt his female alter-ego Rrose Selavy. Openly bisexual in the 1920s, Freytag-Loringhoven's unapologetic sexuality and promiscuity caused much scandal, even among her avant-garde confrères, and sometimes overshadowed the art she created.

Mature Period

Whether the rightful creator of Fountain or not, the Baroness was a pioneer of New York Dada. Freytag-Loringhoven's performances and the use of her body in public spaces were perhaps her most radical assault on rational norms. Her dress, which sometimes included a tin-can bra, a birdcage (with live bird) for a hat, curtain rings as bangles, and an assortment of feathers and tassels, collapsed the distinction between art and life. Freytag-Loringhoven did not simply make Dada artworks to be static objects in a gallery - she lived Dada, making her appearances in public into nonsensical performances. Noted Dada painter Francis Picabia wrote that "Dada speaks with you, it is everything, it envelops everything...." Parading about while wearing absurd objects, Freytag-Loringhoven was a living embodiment of Dada. Freytag-Loringhoven often wore postage stamps on her face and recited her poems in public; her eccentric behavior interrupted the mundanity of day to day life. These notorious performances also made her a figure of legendary status in New York's Greenwich Village.

As early as 1910, Freytag-Loringhoven was arrested for her public appearances in unconventional dress. She continued to pose for artists and to utilize her female, aging body as the site of her art throughout her career. In 1921, Freytag-Loringhoven starred in a film byMan Ray and Duchamp, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven Shaves Her Pubic Hair, in which she performed the action described in the title. Her performance of this mundane, repetitive task highlighted her body as mortal and abject.

Freytag-Loringhoven was not only a visual artist but also an innovative poet, appearing in the avant-garde magazine The Little Review in 1918 alongside James Joyce. A few years later, in 1922, The Little Review published her poem AFFECTIONATE alongside a photograph of her assemblage, Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, a quirky homage to the artist made up of feathers and botanical snippets which rest atop a fractured wine goblet.

Late Period

Despite her many contributions to the avant-garde, the Baroness remained poor and largely unacknowledged for her challenging work throughout her life. In 1923, Freytag-Loringhoven returned to Germany in the hopes of reconnecting with the avant-garde art scene there and thought out an improved financial situation. Instead, she found a homeland devastated by war. Her father had died and disinherited her, leaving her with no choice but to sell newspapers in Berlin to make a living. She depended upon friends and other expatriates to get by, but eventually found herself destitute. Her work from this period is often somber, such as her 1924 painting, Forgotten Like this Parapluice am I by You - Faithless Bernice, which references her relationship with photographer Berenice Abbott, who had financially supported Freytag-Loringhoven, but increasingly distanced herself as Freytag-Loringhoven had become more and more desperate in her final years. Abbott had introduced Freytag-Loringhoven to the writer Djuna Barnes in 1923, who became her artistic collaborator and lover. Barnes kept all correspondence between her and Freytag-Loringhoven and even attempted to write a biography of the artist which was never finished.

In 1926, Freytag-Loringhoven moved to Paris, where she would spend the last year of her life penniless and underemployed. She once again took up posing as a profession at the Montparnasse studios at the Grande Chaumière between 1926 and 1927. Never short of ambition despite her lack of good fortune, Freytag-Loringhoven made plans for her own modeling school to open in the late summer of 1927, calling it her "last dream." This dream was ultimately left unfulfilled, and her attempts to publish new material unsuccessful.

On December 14, 1927, Freytag-Loringhoven and her pets died of asphyxiation in her apartment on Rue Barrault, the gas having been left on. The circumstances of the Baroness's death remain unresolved. It is unclear whether her death was a suicide, or whether she had simply forgotten to turn the gas off. The Baroness is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

The Legacy of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

Though she is little known, Baroness Elsa Freytag-Loringhoven helped to shape the direction of New York Dada with her eccentric public displays and performances as well as with her desire to fuse her sexuality with her art. In the face of accusations that she was "crazy," Freytag-Loringhoven would simply state, "Every artist is crazy with respect to ordinary life." Her gender bending and blatant displays of her sexuality anticipated Feminist art and performance of the mid-20th century. She was an innovative artist whose works paved the way for later experimental Performance art of the late 1950s and 1960s. A renowned poet and a proto-feminist, Elsa and her work have only recently been rediscovered by art historians who have recognized the importance of her contribution to New York Dada. Her provocative poetry was published posthumously in 2011 in Body Sweats: The Uncensored Writings of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. At the very forefront of developing the readymade and performance art, the Baroness holds a legacy as the "Mama of Dada," as the New York Times critic Holland Cotter dubbed her.

Influences and Connections

- Felix Paul Greve

- August Endell

Useful Resources on Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

- Irrational Modernism: A Neurasthenic History of New York Dadaby Amelia Jones

- Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity -- A Cultural BiographyOur Pickby Irene Gammel

- Body Sweats: The Uncensored Writings of Elsa von Freytag-LoringhovenOur Pickby Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven and Irene Gammel

- Holy Skirts: A Novel of a Flamboyant Woman Who Risked All for Artby René Steinke

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI