Summary of Art for Art's Sake

Taken from the French, the term "l'art pour l'art," (Art for Art's Sake) expresses the idea that art has an inherent value independent of its subject-matter, or of any social, political, or ethical significance. By contrast, art should be judged purely on its own terms: according to whether or not it is beautiful, capable of inducing ecstasy or revery in the viewer through its formal qualities (its use of line, color, pattern, and so on). The concept became a rallying cry across nineteenth-century Britain and France, partly as a reaction against the stifling moralism of much academic art and wider society, with the writer Oscar Wilde perhaps its most famous champion. Although the phrase has been little used since the early twentieth century, its legacy lived on in many twentieth-century ideas concerning the autonomy of art, notably in various strains of formalism.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The idea of Art for Art's sake has its origins in nineteenth-century France, where it became associated with Parisian artists, writers, and critics, including Théophile Gautier and Charles Baudelaire. These figures and others put forward the idea that art should stand apart from all thematic, moral, and social concerns - a significant break from the post-Renaissance artistic tradition represented by contemporary academic painting, which favored historical and mythical scenes, and held that art should have a clear ethical message often connected to religion or state power.

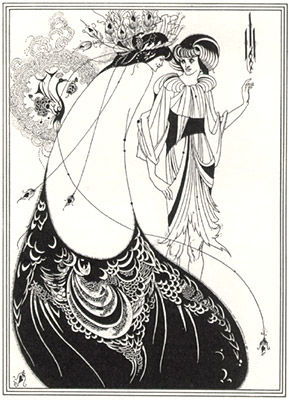

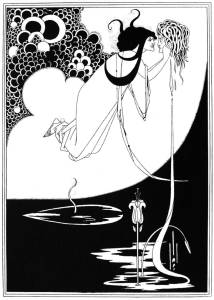

- Although Art for Art's Sake withdrew from all political and ideological concerns, it was nonetheless radical in rejecting the moralizing standards of its day. Artists such as Aubrey Beardsley delighted in shocking polite taste through images which had sexual or grotesque overtones. In this regard, Art for Art's Sake was often implicitly radical, and its program of seeking scandal informed the more politically charged activities of subsequent movements such as Dada and Futurism.

- Although the term Art for Art's Sake fell out of favor by the end of the nineteenth century, the idea it stood for - that art had a value which stood apart from subject-matter, purely connected to formal qualities such as line, color, and tone - remained highly significant. Some such notion is at the basis of all abstractionabstraction, for example. Art for Art Sake can thus be seen to have predicted the work of artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, for example, as well as the work of the Abstract Expressionists.

The Important Artists and Works of Art for Art's Sake

La Ghirlandata

A woman delicately plays a harp while two angels circle pensively above her head. The rich velvet of the woman's green dress flows into the luxurious vegetation that surrounds her, her striking red hair echoed by the garland of flowers and the angels' auburn locks. William Michael Rossetti, the brother of the artist, translated this work's as "The Garlanded Lady" or "Lady of the Wreath," with Alexa Wilding, the model depicted in the center of the work, portrayed as the ideal of love and beauty.

This is a painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a British artist associated with both Aestheticism and the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, and known for his tempestuous and often exploitative romantic relationships with female models and artists. This work's title, along with the idealized treatment of subject matter, may be intended to evoke the spirit of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa (c. 1503-19), then often known as La Giaconda ("the happy one" or "the jocund one"), and revered by critics associated with Art for Art's Sake such as Theophile Gautier and Walter Pater. In effect, Rossetti may have meant his idealized beauty to become an icon for the Aesthetic movement just as the Mona Lisa had become an icon of Renaissance art.

In its guide to the work, the Guildhall Art Gallery notes that the painting ushered in "a new aesthetic of painting," as every element contributed to the elevation of beauty. William Michael Rossetti wrote that his brother's intent was to "to indicate, more or less, youth, beauty, and the faculty for art worthy of a celestial audience, all shadowed by mortal doom." In this respect, the painting summed up the "Cult of Beauty" for which the Pre-Raphaelites stood, and represents an important contribution to the principles of Art for Art's Sake.

Oil on canvas - Guildhall Art Gallery, London

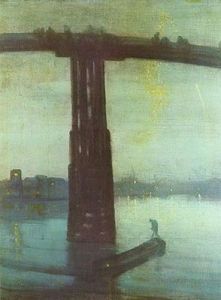

Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket

This iconic painting depicts a firework display at Cremorne Gardens in London. A few shadowy figures can be discerned in the foreground, depicting the shore of the Thames River, but most of the canvas is given over to the black night sky, lit up by the rocket's falling gold sparks and the explosive smoke from the firework battery on the horizon. With its dreamy wash of color and abstracted figures, this painting represented the emergence of a new approach within painting which emphasized the artist's freedom to represent a mood or emotion at the expense of representational accuracy.

This painting, the last in Whistler's series of so-called "nocturnes," became important talismans of the idea of Art for Art's Sake, with the artist stating that "[a]rt should be independent of all clap-trap - should stand alone, and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear." Color and mood were crucial to Whistler's work, with his paintings often bordering on abstraction, while his titles often used musical terms such as "nocturne" and "harmony" to insist on painting's relationship to other artforms, particularly music, which had a 'pure' aesthetic quality not connected to themes or symbolism.

No work is a better example of Whistler's artistic stance. Perhaps for that reason, it became the subject of legal dispute after Whistler sued the noted critic John Ruskin for attacking the painting as worthless and poorly executed. While Whistler won the case, he received only a single farthing in settlement, and his legal fees contributed to his subsequent bankruptcy. Despite this Pyrrhic victory, Whistler's defense played a key role in establishing the principles of art as an entirely liberated pursuit disconnected from all conventions of society, politics, or morality, which would be important to the development of modernism. Art critic James Jones notes that Whistler described a painting as "an arrangement of light, form and colour," an emphasis which predicts, for example, the movement of Abstract Expressionism in the mid-twentieth century.

Oil on panel - The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, Michigan

Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room

The concept of Art for Art's Sake, via the Aesthetic movement, had a transformative effect on interior design and architecture. As art critic Fiona MacCarthy writes, "[o]ne of the main tenets of aestheticism was that art was not confined to painting and sculpture and the false values of the art market. Potential for art is everywhere around us, in our homes and public buildings, in the detail of the way we choose to live our lives."

This photograph depicts the famous Peacock Room, named for the turquoise, gold, and blue murals featuring a peacock motif and designed by James Abbott McNeill Whistler for the home of the shipping magnate Frederick Leyland. Leyland's centerpiece for his dining room was Whistler's painting The Princess from the Land of Porcelain (1863-65), while the interior design embodied Whistler's enthusiasm for Japonism, a style based on western perceptions of Japanese art and design. Whistler described his working process in the room as spontaneous and intuitive: "I just painted on. I went on - without design or sketch - it grew as I painted. And toward the end I reached [...] a point of perfection." He said the finished interior was a "harmony in blue and gold," in effect transforming the space into an artwork and elevating design to a fine art that existed for its own sake.

Whistler's design was enormously influential, informing the development of both the Anglo-Japanese style and the Aesthetic movement, which included all realms of design within its dictum. In a wider sense, the decoration of this room encapsulates the idea so important to exponents of Art for Art's Sake that, by surrounding themselves with beautiful things - not just artworks but walls, tables, chairs, and so on - the artist or art lover could become beautiful themselves.

Oil paint and gold leaf on canvas, leather, and wood - Freer Gallery of Art, Washington DC

The Peacock Skirt

Aubrey Beardsley's stylish ink sketch depicts the Biblical figure of Salome, whose failed seduction of John the Baptist leads to his beheading. Salome was the subject of Oscar Wilde's eponymous one-act tragedy, written in French in 1891. When the English translation was published in 1894, it contained ten woodblock illustrations based on ink sketches by Beardsley, of which The Peacock Skirt is the second. Depicting the figure of Salome to the left in a long, elaborately patterned dress, with a peacock veil and headdress, the work embodies the qualities of elaborate beauty and luxury which Beardsley and other Art-for-Art's-Sake artists promoted. At the same time, the sinister figure to the right, whose made-up face and feminine dress contrasts with their hairy legs, embraces the ideas of androgyny and sexual fluidity with which the movement was (often disapprovingly) associated.

The origins of Beardsley's Salome series are in a single illustration depicting the anti-heroine kissing the severed head of John the Baptist, printed in 1893. Upon seeing the image, Wilde recognized an artistic affinity and invited Beardsley to illustrate the entire narrative. The illustration was heavily influenced by Whistler's decorations for the peacock room, as well as the stylized lines of Japanese woodblock prints; the resultant long, sinuous depiction of bodies anticipates the work of Gustave Klimt and other Art Nouveau artists.

Beardsley contributed much to the Art for Art's Sake approach, in particular developing its connections with Japonism and the decorative arts. At the same time, the Salome series reflects Beardsley's interest in courting and exacerbating the scandal which the Art for Art's Sake movement was already attracting. Salome is perhaps the original femme fatale, ordering John the Baptist killed by her father Herod - himself incestuously infatuated with his daughter - after the Christian prophet refuses her sexual advances. She and her story thus represent a number of themes, such as sexual transgression, incest, and female lust, which scandalized the patriarchal, puritanical Victorian public. In focusing on her as a worthy subject of drama, Wilde and Beardsley were quite deliberately courting controversy, while promoting lifestyle choices such as plurality of gender and sexual freedom.

Woodblock Print - Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge MA.

Fountain

Duchamp's famous artwork - consisting of a mass-manufactured urinal placed on its back and signed with the artist's pseudonym R. Mutt - powerfully challenged the idea of Art for Art's Sake, while also carrying it into new realms. Fountain was submitted to the 1917 Society for Independent Artists and should have been included in the Society's annual exhibition, since membership alone granted the right to exhibit. However, the work was rejected on the grounds of immorality (proving that, despite assumptions to the contrary, other judgments - in this case, morality - did indeed inform aesthetic judgment.) This work bore almost no trace of the artist's input or - so it seemed - creative vision or skill, thus subverting the notion foundational to Art for Art's Sake that a painting or sculpture should have an inherent aesthetic or formal value.

Paradoxically, however, the work's supporters did employ a version of the notion of Art for Art's Sake to defend the object, arguing that Duchamp's mere presentation the urinal imbued it with special significance, as an artwork which he had created. So, if the controversy demonstrated the fading importance of Art for Art's Sake in the 20th century, it also showed the concept's tenacity, as it became part of the foundation of modern art.

As contemporary art historian Peter Bürger wrote, "the autonomy of art is a category of bourgeois society...The relative dissociation of the work of art from the praxis of life in bourgeois society thus becomes transformed into the (erroneous) idea that the work of art is totally independent of society." Bürger noted how "Duchamp's provocation not only unmasks the art market where the signature means more than the quality of the work; it radically questions the very principle of art in bourgeois society according to which the individual is considered the creator of the work of art."

Found object

Full Fathom Five

Full Fathom Five was among the first drip paintings Jackson Pollock completed. Its surface is clotted with an assortment of detritus, from cigarette butts to coins and a key. The uppermost layers were created by pouring lines of black and shiny silver house paint, though a large part of the paint's crust was applied by brush and palette knife, creating an angular counterpoint to the weaving lines. Pollock's drip paintings have been interpreted in numerous ways, some seeing them as inventing a new abstract language for the unconscious, others suggesting that they evoke the night sky, or in this case, the depths of the ocean.

However, the critic Clement Greenberg, who was Pollock's most powerful supporter, insisted that their value lay purely in their formal elements, as he believed in the inherent value of abstract art, arguing that it offered the only means by which to say something new in a world increasingly full of conventional, representational images. He also believed that formal analysis held the key to aesthetic evaluation and that discussion of all other matters - such as theme and subject matter - was irrelevant. As art historian Anna Lovatt states, "the notion of the self-reflexive, autonomous medium propounded by modernist critics - most notably Clement Greenberg," became a leading trend in the twentieth century.

In effect, while the idea of Art for Art's Sake had nominally fallen out of fashion by the early twentieth century, it continued to inform trends in modern art, and its emphasis on the value of art as disconnected from all thematic concerns, became the grounds for Greenberg's concepts of medium specificity, as well as his definition of the avant-garde and his arguments in favor of abstract art. As Lovatt adds, "[b]y emphasizing the opacity and autonomy of each 'medium', Greenberg disengaged the word from its relational and communicative connotations. Thus isolated, the modernist 'medium' was objectified and reified as a thing-in-itself, abstracted from the broader conditions of artistic production and reception."

Oil on canvas, with nails, buttons, tacks, key, coins, cigarettes, matches, etc. - The Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Beginnings

The Literary World and Théophile Gautier

The Swiss writer Benjamin Constant is thought to have been the first person to use the phrase "art for art's sake," in an 1804 diary entry. But the term is most often credited to the French philosopher Victor Cousin, who publicized it in his lectures of 1817-18. The idea of Art for Art's Sake - that art should not be judged on its relationship to social, political, or moral values, but purely for its formal and aesthetic qualities, first became popular amongst writers, encouraged by the French novelist Théophile Gautier. In the preface to his novel Mademoiselle de Maupin (1835), Gautier wrote that "nothing is really beautiful unless it is useless; everything useful is ugly."

Gautier had first studied painting before turning to literature and, subsequently, he became a leading art critic, so that he influenced both the literary and visual-art worlds. The poet Charles Baudelaire, a famous art critic in his own right, dedicated his groundbreaking poetry collection Les Fleurs du Mal (1857) to Gautier, whom he called "a perfect magician of French letters." In 1862 Gautier was elected chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (National Society of Fine Arts) by a board that included Édouard Manet, Eugène Delacroix, and Gustave Doré among others. Gautier's view that aesthetic beauty was central to the value of art, and that thematically suggestive or didactic work often lacked this quality, became widely influential in securing the reputation of the Aesthetic movement.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

The American painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler is generally credited with pioneering the concept of Art for Art's Sake within the visual arts. In his idiosyncratic art manifesto "The Red Rag" (1878) he wrote that "[a]rt should be independent of all clap-trap - should stand alone [...] and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism and the like."

Whistler's assertion that visual art should not promote any particular subject-matter led him to compare it to the purely abstract domain of music. With reference to his "nocturnes," such as Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge (c. 1872-75), he described painting as "pure music," noting that "Beethoven and the rest wrote music [...] they constructed celestial harmonies [...] pure music."

In emphasizing the value of art for its own sake, Whistler helped to establish both the Aesthetic movement and Tonalism, the former movement having great currency in Britain, the latter in North America. In 1893, the critic George Moore, in his book Modern Painting, wrote that, "[m]ore than any other painter, Mr. Whistler's influence has made itself felt on English art. More than any other man, Mr Whistler has helped to purge art of the vice of subject and belief that the mission of the artist is to copy nature."

Aesthetic Movement

By 1860 the Aesthetic movement had emerged, coalescing around the influential idea of Art for Art's Sake, with its base in the United Kingdom. Informed by Whistler's pioneering work and Gautier's criticism, the movement became associated particularly with images of female beauty set against the decadence of the classical world, as exemplified by the work of artists such as Albert Joseph Moore and Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

Aestheticism also overlapped with the worldview of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones, and William Morris. These artists were wrapped up with what has been dubbed the "Cult of Beauty," a concept closely connected to the ideals of Art for Art's Sake, and suggesed that the formal power of the art work mattered above all else. However, many Pre-Raphaelites, such as Morris, were also invested in utopian politics, informed by an idealistic notion of the social structures of the medieval era. This suggests that the ideas of Art for Art's sake informed a slightly wider range of artistic philosophies than is sometimes imagined.

The canonical art critic Walter Pater became a leading proponent of Aestheticism. In his influential book The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry (1873) he stated that "art comes to you proposing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality of your moments as they pass, and simply for these moments' sake." In so doing, he extended the concept of Art for Art's Sake to define the kind of experience that a viewer should derive from a particular artwork, rather than merely applying it to the artist's intentions.

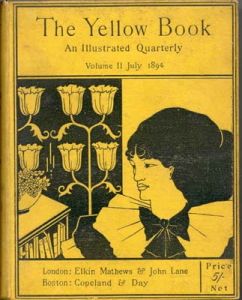

The illustrator and pen-and-ink artist Aubrey Beardsley, who died in 1898 at the age of just 25, played several important roles in the development of Aestheticism - beyond his connection with the more famous Oscar Wilde. Beardsley's sketches, critical commentaries, and editorship of The Yellow Book, a literary magazine published in London from 1894 to 1897, all left their mark on the emergence of formalistic and Decadent strains during the British fin-de-siècle (the end of the nineteenth century). In fact, the literary content of The Yellow Book often represented fairly traditional veins within art criticism, while in terms of visual layout, as the art historian Linda Dowling writes, "[the] asymmetrically placed titles, lavish margins, abundance of white space, and relatively square page declare The Yellow Book's specific and substantial debt to Whistler." Nonetheless, the journal's garish color - which associated it with illicit French novels - and Beardsley's often uncanny and grotesque illustrations, made the journal widely influential and ensured its scandalous reputation.

Decadent Movement

The Decadent movement, which began in the 1880s, developed alongside the Aesthetic movement and shared roots in the mid-nineteenth, with Beardsley a significant figure in both schools. The Decadent movement, however, was particularly associated with France, notably with the work of the French-based Belgian artist Félicien Rops. Rops was a peer of Charles Baudelaire, who had proudly declared himself a "decadent" in his Les Fleurs du Mal ("The Flowers of Evil") (1857), after which time the term became synonymous with a rejection of nineteenth-century banality, puritanism, and sentimentality. In 1886, the publication of the magazine Le Décadent in France gave the Decadent movement its name.

Théophile Gautier, for his part, saw the principles of decadence as reflecting a point of advanced aesthetic and cultural evolution - not to say fatigue and decay - within Western societies. "Art [has] arrived at that point of extreme maturity that determines civilizations which have grown old; ingenious, complicated, clever, full of delicate hints and refinements [...] listening to translate subtle confidences, confessions of depraved passions, and the odd hallucinations of a fixed idea turning to madness." In the Decadent movement, Art for Art's Sake meant not so much an emphasis on pure formal beauty as an ostentatious rejection or mockery of the ideologies and social positions for which art might have been expected to stand.

The Decadents, arguably led by Aubrey Beardsley in Britain - who was also central to the Aesthetic movement - emphasized the erotic, the scandalous, and the disturbing. The Yellow Book pioneered the trend of decadence in art, with Beardsley's drawings rumored in the press to be filled with hidden (or not so hidden) erotic and lewd references, emphasizing his defiance of Victorian moralism. As the art historian Sabine Doran writes, "from the moment of its conception, The Yellow Book presents itself as having a close relationship with the culture of scandal; it is, in fact, one of the progenitors of this culture."

Tonalism

The art of Tonalism, mainly based in North America, held no truck with the scandal-seeking decadence of Beardsley and his peers. However, with their glowing, mist-filled, atmospheric landscapes, the Tonalists pioneered a style that was, in its own way, equally committed to the notion of Art for Art's Sake.

Whistler was a lodestar for these artists. As the art historian David Adams Cleveland notes, Tonalism's "emphasis on balanced design, subtle patterning, and a kind of otherworldly equipoise came directly out of the Aesthetic movement and the work and artistic philosophy of Art for Art's Sake promoted by its greatest exponent, James McNeil Whistler." In works such as Nocturne: The River at Battersea (1878), Whistler emphasized mood and atmosphere while exploring a simplified, almost abstract landscape in terms of its color tonalities.

Art critic Grace Glueck describes Tonalism as "not really a movement, but a mix of tendencies that began to drift together around 1870." "[I]t remained a style without a name," she adds, "until the mid-1890s." Tonalism became a touchstone within US art, associated in particular with the North-American painters George Inness and Albert Pinkham Ryder, as well as the photographer Edward Steichen.

Whistler vs. Ruskin

Many of the principles of Art for Art's Sake were publicly exclaimed by James Abbott McNeill Whistler during a famous libel case, which pitted his views against those of the Victorian art critic John Ruskin. The roots of the dispute were in the founding of the Grosvenor gallery in London in 1877. The gallery promoted the Aesthetic movement, and, as Fiona MacCarthy notes, became a "fashionable talking shop. The gallery's proximity to the Royal Academy polarized opinion about the techniques and purposes of art."

It was this polarization of opinion which led Ruskin, a proponent of more traditional technical and moral values within art, to dismiss Whistler's Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1875), shown in the first Grosvenor exhibition, as the equivalent of "flinging a pot of paint in the public's face." Never shy of publicity, Whistler sued Ruskin for libel, and the case came to court in 1878.

During the legal proceedings, Ruskin used a portrait of Vincenzo Catena's Portrait of the Doge, Andrea Gritti (1523-31), then thought to be painted by Titian, as an example of "real art" meant to counter Whistler's painting. By arguing his right to freedom from pre-imposed artistic standards, Whistler won the case. However, he was awarded only a single farthing in damages, and his legal expenses and the public controversy which the episode had caused severely impacted on his career, to the extent that he was forced to declare bankruptcy, subsequently moving to Paris.

Oscar Wilde and the Aesthetic Movement Teapot

Following Whistler's trial, the British public, as well as a number of powerful cultural figures, turned against the Aesthetic movement, and what they perceived as the indulgence and immorality of Art for Art's Sake. In 1881, the English dramatist W.S. Gilbert premiered Patience, a musical satirizing the leading Aesthetes, while cartoons lampooning Aestheticism appeared frequently in Punch, the leading British magazine of satire and humor.

Oscar Wilde, by this time already an established writer and a cultural celebrity, was often the target for attacks with homophobic overtones. As the art historian Sally-Anne Huxtable writes, he was "the most famous Aesthete of them all [...] at that time dressing in velvet breeches, lecturing on the topic of Art and supposedly quipping that he was 'finding it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue and white china'." In 1882, playing off the success of W.S. Gilbert's Patience, which had included a character based on Wilde called Bunthorne, the designer James Hadley, employed at the famous Royal Worcester Porcelain Factory, created his so-called Aesthetic Movement Teapot.

This piece mocks the ideals of aestheticism, particularly what was seen as its blurring of traditional gender roles. On the base of the pot appears the phrase "Fearful Consequences Through The Laws of Natural Selection & Evolution of Living up to One's Teapot," an allusion to Wilde's comment and to the idea - inferred by the public - that the Aesthetes thought they could make themselves beautiful by surrounding themselves with beautiful objects. (The line also mocks Darwin's recently published and not yet accepted theory of natural selection.) As Huxtable notes, the message of the work embodied "the self-styled 'sensible' and 'manly' world of the Victorian mainstream press", which "saw Aesthetes as effete poseurs." However, she also adds that the work became "the most iconic design object associated with British Aestheticism."

This said, the artistic debate that Hadley alluded to, masked an uglier hostility towards the homosexual tendencies seen to be wrapped up in ideas of Art for Art's Sake. Presenting a young man on one side and a young woman on the other, the teapot suggests the erosion of the traditional masculine and feminine qualities, encapsulating what Huxtable calls "the hysterical fears circulating in the 1880s about the effects that effeminacy and the blurring of gender roles might have on the future British population." These fears placed figures like Wilde in the spotlight, and in 1895, after two trials and much public scandal, he was sentenced to prison and two years' hard labor after being convicted of "gross indecency" for homosexual acts.

Concepts and Trends

Philosophy

The idea of aesthetic experience that informed Art for Art's Sake arguably has its roots in the work of eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant, who held that the true appreciation of art was a process disconnected from all worldly concerns. Subsequent eighteenth- and nineteenth-century artists and thinkers, including Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, and Thomas Carlyle, built upon Kant's ideas. Schiller's Briefe über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen (1795) ("On the Aesthetic Education of Man"), inspired by Kant, developed the idea that appreciating art took the viewer away from social, political, or otherwise 'non-artistic' concerns: "beauty cajoles from [man] a delight in things for their own sake." As a result, when Benjamin Constant first used the phrase "art for art's sake" in 1804, he was coining a memorable phrase that captured an already important philosophical trend.

Art Criticism

A number of nineteenth-century art critics, particularly Théophile Gautier and Walter Pater, did much to establish the ideas of Art for Art's Sake. Pater famously described the possession of an artistic sensibility as meaning "[t]o burn always with [a] hard, gem-like flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life." As art historian Rachel Gurstein writes, "[s]uch an elevated, if extravagant, ideal of art demanded a new kind of criticism that would match, and even surpass, the intensity of the impressions that a painting evoked in the sensitive viewer, and the aesthetic critic responded with ardent prose poems of his own." She adds that "proper Victorians thought such a view of art and criticism immoral and irreligious. They were appalled by what they perceived as its decadence."

Effect on Art History

With their passionate criticism, Gautier and Pater influenced the evaluation not just of contemporary art but also of the Renaissance and classical work that influenced it. Rejecting the story-telling style and moral subject-matter of classical history painting, exemplified by Raphael and favored by the traditional academies, these two critics rediscovered the work of artists such as Botticelli. Additionally, as Rochelle Gurstein writes of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa (c. 1503-19), "[a]lthough many writers associated with the art-for-art's sake movement in France and England paid enthusiastic tribute to the painting, Theophile Gautier and Walter Pater are now best known for launching it on its modern path to what is now inelegantly called 'iconicity.'"

Gautier described the "strange, almost magic charm which the portrait of Mona Lisa has for even the least enthusiastic natures." In his book The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry (1873), Pater called Mona Lisa "the symbol of the modern idea," in a lyrical passage that continues to inform our idea of what the painting represents. As Rachel Gurstein notes, "[i]n an incantatory paragraph, Pater portrayed the Mona Lisa in language that eclipsed Gautier's rhapsody and would relegate Giorgio Vasari to history. Indeed, this single passage so completely formed the imagination and the vision of art lovers who read it that no one - from Oscar Wilde to Bernard Berenson to Kenneth Clark - could speak of the Mona Lisa without uttering in the same breath that he, like everyone else of his generation, had committed Pater's luminous words to memory."

Opponents of Art for Art's Sake

From the beginning, the idea that art should be judged solely on a set of isolated aesthetic or formal criteria was opposed by a range of creatives and thinkers. Academic painters rejected the work associated with Art for Art's Sake as frivolous, lacking the moral purpose offered by the classical subjects which the Academy favored. Ruskin's criticism of Whistler's work encapsulates some aspects of this position.

Just as it was criticized by traditionalists, Art for Art's Sake also gradually fell afoul of emerging avant-garde trends in the arts. Gustave Courbet, the pioneer of Realism, generally seen as the first modern art movement, consciously distanced his aesthetic approach from Art for Art's Sake in 1854, while also rejecting the standards of the academy, presenting them as two sides of the same coin: "I was the sole judge of my painting [...] I had practiced painting not in order to make Art for Art's Sake, but rather to win my intellectual freedom."

Courbet's position anticipated that of many forward-thinking artists who felt, as the novelist George Sand wrote in 1872, that "Art for art's sake is an empty phrase. Art for the sake of truth, art for the sake of the good and the beautiful, that is the faith I am searching for." Modernism and Avant-Garde trends in art increasingly became associated not with a mere decadent rejection of academic and Victorian morals, but with the proposition of alternative social, political, and ethical ideals.

Later Developments

According to the Victoria and Albert Museum, "[t]he Aesthetic project finally ended following the scandal of the trial, conviction and imprisonment of Oscar Wilde for homosexuality in 1895. The fall of Wilde effectively discredited the Aesthetic Movement with the general public, though many of its ideas and styles remained popular into the 20th century." With the decline of the Aesthetic movement, the phrase "art for art's sake" fell out of fashion, though it continued to exert a presence, often notably, in other countries.

In St. Petersburg in 1899 Sergei Diaghilev, along with Léon Bakst and Alexandre Benois, founded the magazine Mir iskusstva ("World of Art"). The magazine was allied with a group of young artists in St. Petersburg which had formed the World of Art movement the preceding year. Promoting Art for Art's Sake and artistic individualism, the group had perhaps its greatest impact through the formation of the groundbreaking Ballets Russes, which Diaghilev founded in 1907, and which operated until 1927.

The idea of Art for Art's Sake had a profound if somewhat paradoxical influence on avant-garde art. As art historian Doug Singsen notes, "the avant-garde was not simply a negation of l'art pour l'art but rather both a negation and continuation of it." Many leading twentieth-century artists dismissed it. Pablo Picasso stated "[t]his idea of art for art's sake is a hoax," while Wassily Kandinsky wrote that "[t]his neglect of inner meanings, which is the life of colours, this vain squandering of artistic power is called 'art for art's sake.'" Nonetheless, the concept was often met with ambiguity. Kandinsky empathized with the concept to a limited extent, describing it as "an unconscious protest against materialism, against the demand that everything should have a use and practical value."

The leading art critic Clement Greenberg, who promoted Abstract Expressionism in the post-World War II era, build his concepts of medium specificity and formalism upon the groundwork of Art for Art's Sake. As art historian Anna Lovatt writes, "Greenberg expanded the concept of art's autonomy as he developed his concept of medium specificity." Contemporary art historian Paul Bürger described the concept of Art for Art's Sake as fundamental to the evolution of the avant-garde and modernism in his influential 1974 text Theory of the Avant-Garde: "the autonomy of art is a category of bourgeois society. It permits the description of art's detachment from the context of practical life as a historical development."

Social historian Rochelle Gurstein notes that "Pater's style was a harbinger of modernity." His influence continued into the twentieth century, particularly among noted critics and writers. Contemporary critic Denis Donoghue describes Pater's influence as "a shade or trace in virtually every writer of significance from [Gerard Manley] Hopkins and [Oscar] Wilde to [John] Ashbery." During the era of postmodernism in literary studies, many critics also took an interest in Pater's worldview as a precursor to modern ideas of "deconstruction." In 1991, scholar Jonathan Loesberg argued in Aestheticism and Deconstruction: Pater, Derrida, and de Man that aestheticism and modern deconstruction produced similar forms of philosophical knowledge and political effect through a process of self-questioning or "self-resistance," and through the internal critique and destabilization of hegemonic truths.

In 2011 the Victoria & Albert Museum held The Cult of Beauty exhibition on the aesthetic movement. As curator Stephen Calloway noted, "the idea of looking at an art movement where, consciously, beauty and quality are central ideas, seems to me extraordinarily timely," suggesting that Art for Art's Sake is an idea with ongoing currency in the information and opinion-saturated contemporary world.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI