Summary of Edward Steichen

Very few artists have had an impact on the American photographic arts to match that of Edward Steichen. From around 1900, he was instrumental in establishing a status for American photography as art through a commitment to the principles Pictorialism. After travels across Europe, and a spell living in Paris, he became acquainted with many of the 20th centuries greatest artists and performers, helping to bring European modernism to the wider attention of the American public through his involvement with the 291 gallery in New York. Steichen joined the American army during WW1 after which he abandoned Pictorialism and painting in favor of Straight Photography. He put his new creativity to use in commercial photography and he is credited by many as having invented what became known as fashion photography. With the onset of WWII, Steichen enlisted once more before resuming his career as Director of the Department of Photography at New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). While at MoMA he curated The Family of Man exhibition, still considered to be the most successful photographic exhibition of all time.

Accomplishments

- With Alfred Stieglitz, he helped form the Photo-Secession group, co-founded the influential quarterly Camera Work and established the famous 291 gallery, and all within the first five years of 1900s. In this early period of his career, Steichen divided his time between impressionistic painting and photography. He mastered the skill of Tonalism and the multi-layered color printing process known as gum-bichromate. By this method he was able to bring an impressionistic mood to his photographic images (and, perhaps, something of his photographic practice to his painting).

- Following his involvement in the first Great War as a member of the Army's photographic division, Steichen abandoned pictorialism and painting altogether in favor of a more direct form of photography. Steichen reached the conclusion that photography should be treated as an artistic medium on its own terms (it should not try to imitate painting in other words). He effectively started afresh as a Straight Photographer. Straight Photography demanded a commitment to high definition and fine picture detail and through it he brought a new standard of graphic excellence to the pages of top quality magazine publications including Vogue and Vanity Fair.

- Through his commercial work, Steichen took many portraits of luminaries from various walks of public life during the 1920s and 1930s. But it was his portraits of the stars of stage and screen that gained him renown as a most brilliant portraitist. Steichen realized the importance of establishing a rapport with his subject and by approaching his portraiture as a collaboration between photographer and sitter he revealed an uncanny ability to capture something of the very essence of their aura.

Important Art by Edward Steichen

Rodin, le Monument à Victor Hugo et Le Penseur

Steichen took several photographs of the virtuoso French sculptor Auguste Rodin. He also made prints of his sculptures and exhibited many of Rodin's sketches and drawings at the 291 Gallery in New York. The two men had become close friends whilst Steichen was living in Montparnasse at the very beginning of the twentieth century. Indeed, Rodin was to become godfather to Steichen's daughter Katherine whose middle name Rodina was chosen in tribute to the sculptor.

In this photograph, Rodin is in profile at the left-hand side of the image, mirroring (on the right of the frame) the profile of possibly his most iconic sculpture, Le Penseur (The Thinker). In the background is another of Rodin's famous works, his Monument to Victor Hugo, a writer whose work the Frenchman greatly admired. (The monument to Hugo is here only rendered in plaster and was not cast in bronze until after Rodin's death.) Both works connect Rodin with the intellectual virtues of art, philosophy and literature and Steichen's aim was to associate himself with these qualities too. By photographing a Modern artist and with two of his artworks, Steichen invokes a sort of four-way conversation (between Rodin, the Thinker, Hugo, and Steichen himself) that places photography, still in its infancy in 1900, as a legitimate tool to expand the dialogue of modernism.

Photograuve - Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Landscape with Avenue of Trees

In his early career Steichen combined painting and photography and one can begin to see here how his painting informed on his photographic work. In Landscape with Avenue of Trees, Steichen clearly shows the influence of Tonalism, an artistic movement that began with the painter James McNeill Whistler in the 1870s. Whistler, who was an acknowledged influence on the young Steichen, was interested in composing his paintings in a way that echoed the composition of musical pieces, but by using color rather than notes. Through this tight compositional structure and focus, Tonalists explored the subtle nuances of color and its possibilities for expressing a given mood (much like music).

This painting shows Steichen's skill in communicating the nuances of expression through a muted color palette. The work almost verges into abstraction through its interplay of dark and light. Though the title alerts us to the "avenue of trees", the shapes in the foreground are not necessarily very easy to make out, and the landscape itself is only faintly depicted. The moon peeks out from just behind the foliage of the tall tree, casting a glow around the edge of its shape and causing an almost ripple effect of light across the sky itself. It is an image that demands our concentration, Steichen is encouraging his viewer to look (and look again) in order to determine the distinctions in color, shape and line.

Oil paint on canvas - Private Collection

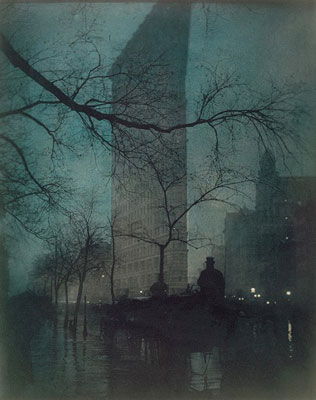

Flatiron Building

Steichen's interest in the interrelationship between photography and Tonalist painting is evident in his famous images of the Flatiron Building. Located at 175 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, the Flatiron building was one of the tallest in the world upon its completion in 1902, and was truly unique due to its shape. This image was first seen publicly at the "International Exhibition of Pictorial Photography" held in Buffalo, New York in 1910. It was in fact one of six hundred images selected by Alfred Stieglitz as a means of showcasing the artistry of Pictorialist photography. Steichen's photograph, which highlights his feel for shapes and textures, became one of his most famous images and it is easy to see a relationship here with his painting Landscape with Avenue of Trees. The building of the title looms disconcertingly in the background, a large shadow in the centre of the frame. Steichen omits the tip of the building, as if, perhaps, its sheer scale could not be contained by the frame.

This image was produced at the height of Steichen's Pictorialist period with the Photo-Secession group. At this time he was interested in adapting and manipulating his photographs and here he colorized the image using layers of pigment in a light-sensitive solution. The image actually exists in three versions, each with a slightly different tone and feel, demonstrating how powerful color can be in altering mood. With this print, his aim was to capture something of the nuances of light in the early hours of the evening. As Professor William Sharpe observed: "Night is a time of dreaming, of freeing repressed libidinal energies, and photographs such as this subtly exploit the suggestive properties of urban landscape, using a symbolic language to disclose truths [that would be] hidden at midday."

Gum bichromate over platinum print - Gum bichromate over platinum print

Moonlight: The Pond

This image was taken in Mamaroneck, New York, when Steichen was visiting his friend, the art critic Charles Caffin. It depicts the moon rising behind a clearing of trees, and then reflected onto a completely still pond. Like Flatiron, Moonlight: The Pond uses light and shadow in an extraordinarily evocative and haunting way.

Steichen demonstrates here once more his interest in Tonalism. His landscape is "washed" in a color tone to form a finished mist-like effect. The interplay of light and dark, and the broad dark washes laying across Steichen's palette, were then fully in keeping with the pictorial preferences of the Photo-Secession group. Though the image might appear to be quite simple, it is in fact a complex emotional composition in the way it manipulates its light sources. The moon peaks above the horizon and glows brightly through the trees; its center-frame positioning, meanwhile, suggesting a precise and studied compositional set up. Responding to this image in Camera Work, Caffin confirmed Steichen's credentials as a bone-fide photographic artist through this rather poetic reading: "It is in the penumbra, between the clear visibility of things and their total extinction into darkness, when the concreteness of appearances becomes merged in half-realised, half-baffled vision, that spirit seems to disengage itself from matter to envelop it with a mystery of soul-suggestion."

Getty Center

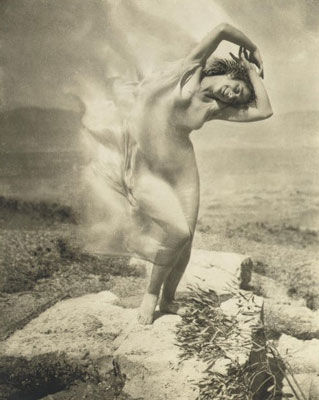

Wind Fire, Thérèse Duncan on the Acropolis

In this astonishing image, made after he abandoned his interest in Tonalism, Steichen captures an otherworldly energy in the movement of Thérèse Duncan, the adopted daughter of the renowned dancer Isadora Duncan. Steichen met Isadora when she was in Venice with her dance troupe. He then followed her to Greece in the hope of being able to photograph her dancing on the Acropolis. In the end, however, it was Thérèse and not Isadora that he photographed on the rocks above the citadel. The image was first published in Vanity Fair in 1923 accompanied with a caption by the poet Carl Sandburg (Steichen's brother-in-law) which read: "Goat girl caught in the brambles . . . let it all burn in this wind fire, let the fire have it..."

In the photograph, the exuberant Thérèse has contorted her body; her knee is cocked, and her arms are cradled over her head in an almost Classical female pose. She stands on uneven rock with some leaves of wild-plants in the foreground, but it is her billowing dress that grabs our attention. The translucent material both hides and reveals her body. Thérèse appears to us as almost naked in fact. Steichen said the following about the image: "She was a living reincarnation of a Greek nymph [...] The wind pressed the garments tight to her body, and the ends were left flapping and fluttering. They actually crackled. This gave the effect of fire." Steichen has managed to capture a timeless image here in the way the modern and the classical meet.

Gelatin silver contact print - Private Collection

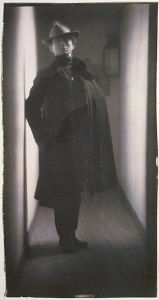

Gloria Swanson

This portrait of silent movie star Gloria Swanson is one of Steichen's most celebrated works. It merges the worlds of portraiture and fashion photography to spellbinding effect. The image was later published in the February 1928 issue of Vanity Fair to help publicize Swanson's new film Sadie Thompson.

Journalist, critic and editor of Vanity Fair Frank Crowinshield referred to Steichen as the "world's greatest living portrait photographer" and in this portrait one can appreciate his point. The most striking element of the picture are the Star's hypnotic eyes that look directly into ours. Given that they had no voice, it was the norm for silent film stars to convey their screen presence through their eyes. Indeed, Swanson was widely recognized for her wide-eyed look and by emphasising them in this image, Steichen acknowledged her intelligence and her skill as a performer. In this way, the portrait celebrates both her standing as an artist and her qualities as an individual. Steichen wrote about the photography session in his autobiography: "At the end of the session, I took a piece of black lace veil and hung it in front of her face. She recognized the idea at once. Her eyes dilated, and her look was that of a leopardess lurking behind leafy shrubbery, watching her prey. You don't have to explain things to a dynamic and intelligent personality like Miss Swanson. Her mind works swiftly and intuitively." In this description, Steichen acknowledged that if one is to strive for the very best portraiture, then there must first be a true affiliation between sitter and artist.

Gelatin silver print - Private Collection

The Maypole, Empire State Building

During the first half of the twentieth century, New York came into its own. There was considerable public fascination with skyscrapers and demand for architectural photography and magazine features was high. Steichen was thus commissioned by Vanity Fair to photograph the Empire State Building, at that time the world's tallest building, and arguably the modern world's greatest architectural achievement.

Faced with the problem of capturing the true majesty of this iconic landmark, Steichen prepared for his assignment with the same thoughtfulness with which he approached his portraiture. In order to capture the building's true stature, Steichen devised a strategy whereby he photographed the building frontally and cater-cornered before then superimposing one negative on top of the other. The end effect, in which Steichen renders the building's power in three dimensions, is astounding. As for the images title, Steichen said "I conceived the building as a Maypole...to suggest the swirl of a Maypole dance" (a city centrepiece, indeed, around which the proud denizens of New York might come to rejoice).

In 1951, MoMA initiated an "Art Lending Service" which operated into the early eighties. The lending service was devised by the museum's Junior Council to encourage art collecting amongst its members and/or the general public. Selected works were available for rent for three months at a time, after which, the patron was free to buy or return the work to the museum. The Maypole was one of the most popular images to pass through the "Art Lending Service". According to MoMA's own publicity, The Maypole's popularity was "testament [to] the technological advancements in architecture as much as in photography, and [to] the iconic legacy of one of the sharpest eyes to have captured both."

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

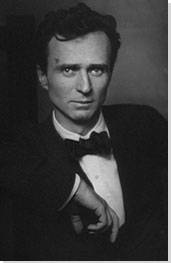

Biography of Edward Steichen

Childhood and Education

Eduard Jean Steichen was born in Bivange, Luxembourg in 1879. His father, Jean-Pierre, moved to the United States the following year; Eduard and his mother, Marie, following in 1881, once his father had secured work in the copper mines in Hancock, near Chicago. Eduard's sister Lilian was born soon thereafter in 1883. The Steichen family moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1889, where, due to Jean-Pierre's deteriorating health, Marie took on the role of breadwinner, working as a milliner.

When he was fifteen, Steichen started an apprenticeship in lithography with the American Fine Art Company of Milwaukee. Before long he had showed an aptitude for drawing and moved quickly through the ranks to become a lithograph designer. He bought a second-hand camera in 1895, and began teaching himself how to take photographs. He was also studying painting in his spare time and his first forays into photography duly replicated the painterly techniques of the Pictorialist style that was in vogue at the time. His employers were impressed with his photographic work and insisted that the company's designs should come from his work from then on. Soon thereafter, Steichen and a select group of friends formed the Milwaukee Art Students League. The League rented a room in a downtown building to work in and to host lectures. In 1899, Steichen's photographs were exhibited in the second Philadelphia Photographic Salon next to those of Alfred Stieglitz and Clarence H. White. The event proved to be a prelude to a fruitful professional relationship between the men.

In 1900 White wrote to Stieglitz to suggest he meet with Steichen. The meeting was a success; so much so in fact, Stieglitz become Steichen's early mentor and collaborator. Stieglitz, who was 13 years Steichen's senior, and who had already made a reputation for himself, bought three of Steichen's prints (for $5 each). Those were the first prints Steichen ever sold. That same year, Steichen became a naturalised citizen of the U.S., changing the spelling of his name from "Eduard" to "Edward".

In October 1900, the Boston photographer F. Holland Day put on an important exhibition entitled The New School of American Photography at the London headquarters of the Royal Photographic Society. Some of the content of exhibition shocked the British press and public: indeed, The Photography News claimed that the collection had been "fostered by the ravings of a few lunatics." There was some disquiet about the School's "progressive" Pictorialist method (having clashed with Day, Stieglitz had refused to partake in the exhibition) but the annoyance was aimed mostly at Day (an individual who courted controversy, and who modelled himself on Oscar Wilde) for his homoerotic images featuring naked black men and a self-portrait in which he presented himself as Christ. Yet amidst the furore, the 22-year-old Steichen was singled out for giddy praise.

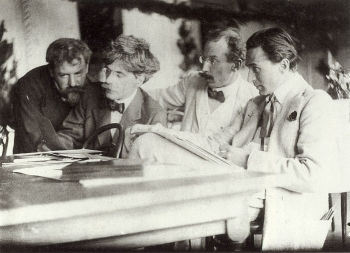

Between 1900 and 1902 Steichen had taken a studio on the bohemian Left Bank area of Paris. His connections with European modernists proved very useful for his next co-endeavor with Stieglitz: the gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue. Trading between 1905 and 1917, and officially called the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, it soon became known simply as 291. Thanks to Steichen's French connections, the 291 gallery was responsible for introducing the work of up and coming (and now legendary) French avant-gardists to the American public. In its first five years of operation, the gallery had exhibited works by the likes of Rodin, Cezanne, Matisse and Picasso.

In 1902 Steichen and Stieglitz established the artistic group Photo-Secession, a collective of photographers including White, Eva Watson-Schutze, William B. Dyer and Edmund Stirling. The group wanted to celebrate the photograph as art, but with a particular emphasis on Pictorialism, and the range of techniques that could be used to manipulate and alter the original composition. The birth of Photo-Secession coincided more-or-less with the inaugural edition of the influential quarterly Camera Work. Established by Stieglitz and Steichen, Camera Work, for which Steichen designed the logo and page layouts, and contributed essays, ran from 1903 to 1917. The second edition was devoted almost exclusively to Steichen's work and during its 14 year history, Steichen became Camera Work's most frequent contributor (with some 70 entries). Steichen's involvement with the magazine was interrupted in 1906 however when he returned to Paris with his family - Steichen had been married in 1903 to Cara E. Smith, a musician he met on his earlier visit to Paris - until 1914. Though he was still able to contribute to Camera Work, his primary motivation for returning to the French capital was to concentrate on his painting.

Mature Period

In 1910, divisions had started to arise between members of the Photo-Secession, due to differing opinions on the wavering artistic credibility of Pictorialism. There was a new call for a pure photographic style that would bring new perspectives and detail to ordinary or previously ignored subjects in the name of fine art. The new aesthetic took inspiration in the second half of the decade from Paul Strand whose "Straight" aesthetic condemned all forms of Pictorialism. The Photo-Secession group dissolved around this time, and Steichen himself started to move into commercial photography. In 1911, he was commissioned to take photographs for the French magazine Art et Décoration. His images were to accompany a piece on the French fashion designer Paul Poiret, and are now widely considered to be the first examples of fashion photography.

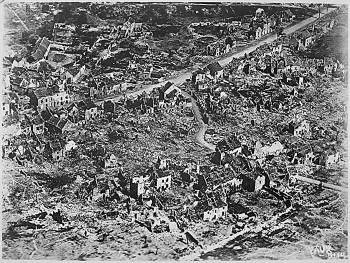

When the U.S entered the First World War in 1917, Steichen joined the Army and helped create the photographic division, eventually becoming commander and head of aerial photography. In this role, he had to change his approach to photography, abandoning his Pictorialist style for a more exacting, realist method. The war also signalled a final break between himself and Stieglitz. Firstly, Stieglitz disapproved of Steichen's move into commercial photography and, secondly, the men had opposite views on the war. Stieglitz, a German, was primarily worried for the safety of his family and friends in Germany. He was also troubled by practical and commercial concerns such as the fact that he needed to find a new printer for the photogravures for Camera Work, which had been printed hitherto in Germany. For his part, Steichen supported America's involvement in the war and he was more concerned for the fate of Luxembourg (the country of his birth) and his beloved France. By the time the war had ended, Steichen had completely reappraised his photographic technique, and abandoned Pictorialism and painting altogether. He commented that: "As a painter I was producing a high grade wall paper with a gold frame around it [...] we pulled all the paintings I had made out into the yard and we made a bonfire of the whole thing [...] it was a confirmation of my faith in photography, and the opening of a whole new world to me."

He and Clara divorced in 1922 after several years of acrimony. The couple had two daughters, Katherine and Mary, but they had a difficult relationship with their father due in part to Clara's accusations of Steichen's infidelity. Steichen married actress Dana Desboro Glover in 1923. The same year, he returned to the world of fashion, and took up the post of chief photographer for Condé Nast, the publisher of high-end fashion magazines such as Vogue and Vanity Fair. Steichen then effectively transformed the world of fashion photography by making his haute couture images more animated and more inventive. He also took several portraits of dignitaries and Stars of stage and screen including Lillian Gish (as Ophelia), Marlene Dietrich, Gloria Swanson, Greta Garbo and Paul Robeson. Of his shoot with Robeson, Steichen said the following: "In photographing an artist, such as Paul Robeson, the photographer is given exceptional material to work with. In other words, he [the photographer] can count on getting a great deal for nothing, but that does not go very far unless the photographer is alert, ready and able to take advantage of such an opportunity."

Later years

After working for 15 years in the fashion industry, Steichen closed his studio on January 1st, 1938. When World War II broke out, Steichen took up his second military post as Director of the Naval Aviation Photographic Unit. During his service (through which he rose to the rank of Captain) he produced two shows - The Road to Victory and Power in the Pacific - for the Museum of Modern Art, and directed his only film, a documentary entitled The Fighting Lady. The film followed the life of an aircraft carrier of the same name and won the Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1945.

Following the war, Steichen served as Director of the Department of Photography at New York's Museum of Modern Art between 1947 and 1961. In 1955 he curated and assembled the exhibit The Family of Man, an exhibition that travelled across the world and was seen by an estimated nine million people over eight years. The exhibition, the most famous photographic exhibition of all time, brought together works by two hundred and seventy-three different photographers, including the likes of Ansel Adams, Diane and Allan Arbus, Robert Frank, Nora Dumas, Lee Miller, Henk Jonker, and August Sander. Steichen had worked on the selection of images for two years and wanted to show the wide range of experiences photography can capture. In the press release from the time he said "[The photographers] have photographed the everyday story of man - his aspirations, his hopes, his loves, his foibles, his greatness, his cruelty his compassion, his relations to his fellow man as it is seen in him wherever he happens to live, whatever language he happens to speak, whatever clothes he happens to wear."

In 1957, Dana, his wife of 34 years, died of leukaemia. Three years later the 80-year-old Steichen married the copywriter Joanna Taub, 53 years his junior. They remained together until his death in 1973 when she became the guardian of her husband's legacy. While in his last year at MoMA, a 14-year-old boy named Stephen Shore rang Steichen to ask if he could show him some of his photographs. Admiring of the boy's audacity, Steichen allowed him an appointment and bought three of the images. Shore, known predominantly for his color photography, has gone on to have a long and laureled career.

In 1963 Steichen published his autobiography A life in Photography. He died on March 25th, 1973 at the age of 93 in his home on a farm in West Connecticut.

The Legacy of Edward Steichen

Steichen's place in the pantheon of photographic greats was secured as a young man through his contribution to three interlocked bodies: the Photo-Secession group; Camera Work and the 291 Gallery. With his colleagues he was instrumental in establishing a permanent footing for photography amongst the modern plastic arts and as such his influence can be traced through a range of photographic genres. He made the most personal impact however on fashion photography and magazine portraiture. The renowned photography historian Beaumont Newhall put it perfectly when he said that "Armed with his mastery of technique, and with his brilliant sense of design and ability to grasp in an image the personality of a sitter, [Steichen] began to raise magazine illustrations to a creative level." Curators and art critics William A. Ewing and Todd Brandow went further still when they suggested that Steichen "was among a tiny band of talented photographers who elevated celebrity portraiture from the status of formulaic publicity stills to an aesthetically sophisticated genre in its own right."

Through Steichen is primarily - and rightly - known through his photography, he was also crucial in bringing the works of highly distinguished French artists such as Rodin, Cézanne and Matisse to the United States. His curation of Family of Man exhibition, meanwhile, suggested new possibilities for photographic portraiture as at once an art form and a means of reaching a more nuanced understanding of the complexities of humankind.

Steichen was the recipient of numerous awards and honors in his lifetime including the Presidential Medal of Freedom (for his work in Photography) in 1963. He has been the subject of books and exhibitions and in 1974 he was inducted (having already served on its advisory board) into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum. In 1994, meanwhile, The Family of Man Exhibition found a permanent home in Luxembourg (Steichen's birthplace) where it is housed in the Steichen Museum. Perhaps the last word on his legacy should go to the esteemed American poet Carl Sandberg who said this of Steichen's work: "A scientist and a speculative philosopher stands [at the] back of Steichen's best picture. They will not yield their meaning and essence on the first look nor the thousandth -- which is the test of masterpieces."

Influences and Connections

-

![Alfred Stieglitz]() Alfred Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz ![Clarence White]() Clarence White

Clarence White- Gertrude Käsebier

- Eva Watson-Schütze

-

![Paul Strand]() Paul Strand

Paul Strand -

![Robert Frank]() Robert Frank

Robert Frank -

![Richard Avedon]() Richard Avedon

Richard Avedon -

![Stephen Shore]() Stephen Shore

Stephen Shore - Bruce Weber

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI