Summary of George Inness

George Inness's atmospheric, illustrative compositions represent a vital contribution to nineteenth-century North American landscape painting. At the same time Inness is noteworthy for his resistance to many of the generic trappings associated with that era. Whereas contemporaries such as Thomas Cole and Frederic Edwin Church forged a distinctively American approach to the Romantic landscape, Inness was interested in exploring and turning to new effect the European Romantic origins of their work. His early works, in their soft brushwork and emphasis of light and tonal effects, suggest the proto-Impressionism of Camille Corot, and were directly influenced by the French Barbizon School. Later works take on the bold painterly effects of J.M.W. Turner. At the same time, Inness was a recalcitrant and obdurately individualistic figure, his fierceness vital in ensuring the singularity of his work. He remains a potent force in the history of modern American painting.

Accomplishments

- While the pioneers of the Hudson River School struck out from European Romanticism to forge a distinctively North American brand of landscape painting, George Inness remained a committed Europhile throughout his life: a commitment which, ironically, made him amongst the most unique painters of the Hudson River generation. Whereas the artists of that school set out across the wider American continent in search of new subject-matter, George Inness - who was actually born in the Hudson Valley - sought inspiration in the classical ruins and hillsides of Italy, and the dense forests of rural France. In this sense, his work arguably registers as contribution to mid-century European Naturalism as well as the era of the classic American landscape.

- George Inness's landscape paintings offer us a cultural space as much as a natural space. The vogue in nineteenth-century American painting was for vast canvases in which all human activity was excised from the scene to suggest an untamed wilderness. But Inness was more concerned with expressing the interaction of humankind with the landscapes which they made their own. In this sense, his paintings represent a uniquely optimistic view of social progress in the nineteenth century: they are monuments to a process of industrialization and urbanization that, it was felt, might bring about a new era of harmony between humanity and nature.

- Throughout his life Inness remained committed to studio working, and to an idea of the landscape painting as a synthetic composition, bringing together elements of the real and the fictional, which was rejected by painters such as Frederic Edwin Church. Though Church's landscapes were as imaginative and - in a positive sense - artificial as Inness's, Inness was unique in foregoing the cult of fidelity to nature and plein air technique that defined much of the Hudson River generation.

Important Art by George Inness

The Lackawanna Valley

This is one of George Inness's earliest pieces, produced while he was still a struggling young artist for the first president of the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad. Inness was paid $75 for the composition, which includes a mixture of pastoral and industrial elements. A picturesque scene of fields on the outskirts of Scranton, Pennsylvania is cut through with the tracks of the growing railroad. In the foreground we see stumps of trees felled to make way for progress, and the figure of a reclining man looking on at the approaching train. (The scene was in fact partially invented: Inness was aggrieved to be asked to add more tracks than existed, exaggerate the prominence of the roundhouse, and paint the company logo on the train.) Two sets of track meet in the middle, leading the eye to the steam engine and its roundhouse beyond. Beyond this, the eye is drawn to the steeple of a church, picked out in black beyond the white locomotive steam, while further afield the gentle Pennsylvanian hills are rendered in calming blues and purples.

For its unique status to be appreciated this work should be compared with prominent landscape paintings of the time. Two years later Frederic Edwin Church would produce his majestic Niagara, a work which shows no human history, no industry, and no progress, merely the unfettered power of nature at work. Inness by contrast chose - or was paid - to depict human civilization in nature, and as such, the bucolic Lackawanna Valley is an ambiguous work. The scene and color palette are calm and harmonious, but the scarred tree trunks in the foreground, emerging from the earth almost like marks of disease, raise questions about the artist's message. This synthesis of natural and manmade elements predicates the work of Precisionist artists such as Charles Sheeler.

The work has become one of Inness's most famous, but it went through a period of neglect. It was lost and the artist amazingly found it years later collecting dust in a curiosity shop in Mexico City. He brought it for a few dollars and gleefully brought it home. The curator Nicolai Cikovsky Jr. described it as "a great and compelling painting,...The Lackawanna Valley is a masterpiece not because of its subject, but because it is painted with such sensitivity and authority, such beauty and power."

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

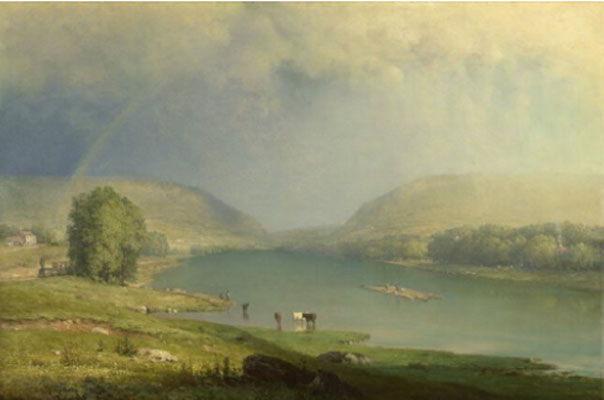

The Delaware Water Gap

This work, like The Lackawanna Valley, depicts the emerging North-American steam train network, but the prominence of the locomotive is far more diminished. He we see the Delaware Water Gap on the border of Pennsylvania and New Jersey. In the foreground, the rocks and grasses are darkened by cloud-cover, which are luminously rendered above, predicating the effects of Tonalism. The work also hints at the effects of Impressionism; although Inness would dismiss the school on a trip to France 13 years later, this work partly comprises a delicate study of light in the style of European proto-Impressionists such as Corot. A rainbow arcs from the earth to the left of the canvas, while the drizzle and mist are rendered in glazes of white and yellow as rain falls on the Kittatinny Mountains. In the flat, tranquil water cows wallow, while figures bob on a raft beyond, up the Delaware River. Houses are picked out among the trees while a small dark train steams out of the canvas to the left. Again, we see the contrast of man and earth, nature and machine, working together in quiet harmony.

Inness painted this scene more than any other subject throughout his career. Critics have suggested that for the young artist the scene presented a quintessential image of human progress. As Cikovsky stated, "[i]ts combination of natural beauty and the railroad, rafts and felled trees that exemplify human enterprise made it a pictorial type of definite meaning." In this rendering of the scene Innes broke from the carefully executed attention to detail which became associated with the Hudson River School, showing his desire to explore more painterly techniques, and the autonomous qualities of color.

In retrospect, the work seems rich with the combined influences of Dutch landscape painting and the expressive brushwork of the French Barbizon school, a movement that had a huge influence on the artist. Corot was cited by Inness as one of the finest landscape artists in existence, and his influence here is clear. As the cultural historian James Thomas Flexner put it, "[h]owever American [Inness's] work would have looked in France, it looked very French in America."

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, London

Peace and Plenty

Inness continued to battle the artistic norms promoted by the Hudson River School into the middle years of his career, as exemplified by this large and lush canvas. Favoring the pastoral over the grandiose, Inness renders Peace and Plenty in soft brushstrokes of copper, gold, and green, heralding the beginnings of the Tonalist movement as he carefully plays with color and composition to suggest spiritual harmony. Here we see workers setting down their tools at the end of a long day of harvesting. The fruits of their labors, sheaths of wheat tethered and piled, shine in the warm golden twilight. Inness again brings together nature and industry, with the enveloping glow of the sunset, hidden behind the central tree, uniting the different elements of the scene. The slow-moving river, the distant houses, and the blue and pink sky, all convey a sense of peace, a mood emphasized by Inness's use of enriched pigments.

If works such as The Delaware Water Gap represent the influence of European mid-century landscape painting, Peace and Plenty is strikingly reminiscent of early-nineteenth-century British Romantic landscape painting; John Constable seems a particularly suitable point of reference. In terms of cultural-historical resonances, meanwhile, the work was painted towards the end of the civil war, and seems to reflect the slowly emerging mood of a nation at peace.

The curator Leo Mazow offers a detailed, schematic reading of the work, suggesting that it reflects three different views of history: cyclical, millennial, and progressive. Firstly, the painting alludes to the cyclical view of history offered in Genesis, which presents alternating states of feast and famine, but it also references millennial, Swedenborgen notions of a 'New Jerusalem' or promised land that could be forged on American soil. Finally, Inness codifies a progressive view of the advent of industrialization, that he felt, in contrast to some of his Hudson River School contemporaries, might herald a new era of civility, defined by the peaceful coexistence of man and nature.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Monk

This is one of Inness's more mysterious and evocative works, characteristic of his deeply spiritual nature. The piece shows a white shrouded monk walking with his head bowed in the twilight. His advancing years are suggested by his bowed spine and the hint of a stick, implied by a single dab of white paint. The figure walks in the darkness amongst the olive trees of Albano, in Inness's beloved Italy, while enormous black silhouetted pines tower over him forming a horizontal band across the yellow and ochre sky. The scene is set in Villa Barberini, near Castel Gandolfo, a summer residence of the Pope. As such, it was frequently depicted in religious and landscape art of the time.

Cikovsky held that the work's flatness and 'occult' balance indicated the influence of Japonisme, a stylistic move not characteristic of Inness at any other point in his career. The work also hints at the predilection for decorative crafts that would take the art-world by storm at the end of the century. A Washington Post article from 1986 notes that "Inness flirted with overt symbolism in The Monk, a moody picture that, in its flat and rigid patterning anticipates the linearity of Art Nouveau." At the same time, the work forges a clear intertextual link with Caspar David Friedrich's classic work of Romantic genre painting The Monk By the Sea (1808-10).

This remains one of Inness's most striking and singular works, "collapsing space and flattening objects to shape", as Cikovsky puts it, to transform the romantic staple of the scene presented. For Adrienne Baxter Bell, paintings such as The Monk are as "[e]ndlessly compelling as reflections of nature's physical beauty", and "invite us to set aside our inclination to identify recognizable places in the natural world. Instead...we might begin to contemplate an unknown, imaginary, perhaps even spiritual existence."

Oil on canvas - Addison Gallery of American Art, Massachusetts

Niagara

This bold work represents a late stylistic departure for Inness. He returns to the themes of the great American landscapists, but whereas Frederic Edwin Church's famous painting of the Niagara Falls (1857) offers mesmeric hypernaturalism, Inness opts instead to express the noise and power of the falls through expressive paintwork and romantic color effects. The viewer is placed in an elevated position on the American bank, looking towards the bottom fifth of the canvas, which is populated in the foreground by shrubbery and people. Most of the composition, however, is given over to the blues and greens of cascading water, crashing noisily into the center of the composition and giving way to clouds of vapor. A dark and stormy sky makes up the top third of the composition; but whereas a common device of the Hudson River school was to omit all signs of human or industrial activities, Inness depicts a towering chimney belching out purple smoke that merges with the gray black sky.

Niagara Falls was a favorite subject of Inness's, one which he returned to nine times across his career. This version of the scene offers us a typically bold and idiosyncratic combination of influences, reminding us both of the late seascapes of J.M.W. Turner and perhaps the smoky nocturnes of the American Impressionist James Abbott McNeill Whistler. In terms of compositional fidelity the smokestack is a characteristically ambiguous feature. At the time of painting the chimney had been destroyed; as the art historian Alexander Jackson asks, therefore, "[c]ould [Inness] have been drawing attention to the negative impacts of human activity on nature? Or was he simply concerned with the harmonious tonal effects created by the combination of clouds, smoke and spray? The composition of the painting draws attention to the smokestack, yet the smoke itself does not seem threatening, as its pinkish-gray hues melt into the dark gray skies." Either way, the work is a perfect example of Inness's use of Tonalist effects, utilizing the loose painterly style typical of the school, that emphasized atmospheric effects over naturalistic detail.

Joshua Taylor, former director of National Collection of Fine Arts, wrote that when viewing Inness's paintings of his later period, "we are thrown back upon our emotional responses, set free to wander not only in the undefined washes of color in the landscape, but also pleasurably in the reaches of the mind."

Oil on canvas - Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

Sunset in the Woods

This work, painted just three years before Inness's death, exemplifies his ongoing commitment to independence as an artist. There is not so much a story to be told by the piece as a feeling to be conveyed, presented through the image of a dark, almost magical-seeming wood at twilight. No human figures or animals can be seen, and the gloaming obscures most of the detail. Illuminated in yellow golds, the canvas draws the eye to a beech tree in the center-right, met by a horizontal band of green forest-floor stretching across the lower center of the work. A looming rock structure blocks out light from behind. Beyond this, a strip of green light can be seen, with further illuminated trees in the background. The overall impression is of an ethereal and ghostly silence.

Inness did not often comment on his individual works, but he did talk about this piece the year it was completed: "I commenced this picture several years since but until last winter I had not obtained any idea commensurate with the impression received on the spot. The rocks and general formation are like the place but the trees, especially the beech, are increased in size. The idea is to represent an effect of light in the woods toward sundown but to allow the imagination to predominate." This work shows more clearly than ever the effect of Swedenborgen philosophy on the artist's work. As the art historian Sally Whitman Coleman notes, "Inness...believed that everything in nature had a mystical component, which he conveyed in his paintings with asymmetrical and balanced compositions, forms with softened edges [and] saturated color."

Whether or not we hold to the mystical conceptual underpinnings of the piece, Sunset in the Woods has an undeniably powerful effect, reminiscent of some of the sylvan scenes of the later, Russian Peredvizhniki school, but with a magical quality that is entirely unique to the artist. As Cikovsky puts it, "weight is suspended, time is slowed, sound is stilled, substance is softened, atmosphere is unbreathably substantial and thick with color."

Oil on canvas - Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Biography of George Inness

Childhood and Early Training

George Inness was born in 1825 near Newburgh, in the mid-Hudson River valley. He was the fifth of thirteen children born to Clarissa and John Inness, a farmer and grocer. The family moved to Newark, New Jersey when he was five and he was encouraged to read and learn about art. His father wanted Inness to become a grocer but he had other ideas, and at the age of 14 he took up drawing lessons. His father was well-off and could provide for his son's teaching but nonetheless his early artistic education ended here. Inness was a small child and suffered from epilepsy, which he cited as the reason for his lack of a formal education. But he was reportedly inspired by one of his father's books on art, which he would read and re-read, especially fascinated by the paintings of Claude Lorrain.

At the age of 16 he was employed as an engraver: a common route for aspiring artists at the time. He was employed in New York first by Sherman & Smith, and then N. Currier. He was inspired by the work of Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, artists who would have an influence on his later work. In 1839 he met the traveling painter John Jesse Barker, who became his first real teacher and is thought to be partly responsible for Inness's skill as a colorist. His main mentors, however, were the Old Masters; he loved to study and work from European art and his compositions show the clear influence of Claude Lorrain and Salvator Rosa.

In 1843 he caught the attention of the French artist Régis François Gignoux, a painter associated with the Hudson River School who specialized in snow scenes, and who offered Inness a month's instruction. Inness would go on to associate with many from the group. But although he worked alongside them, producing distinctly American landscapes, Inness's aims and methods were notably different from the school's, as reflected by the influence of Gignoux. A pupil of Paul Delaroche, Gignoux was inspired by the great traditions of European painting and passed his Europhile passions on to his young pupil. In 1844 Inness held his first exhibition at the National Academy of Design, where he was received as a "young artist with good promise". In 1845 he opened his own studio in New York.

In 1849, George married Delia Miller, about whom little is known. She died a few months later and the following year Inness was remarried, to Elizabeth Abigail Hart, with whom he would have six children.

Mature Period

During the 1850s peers of Inness's from the Hudson River School such as Frederic Edwin Church were departing on tours across the American hemisphere - including the Andres - to seek out new subject matter for their landscape painting. Inness, by contrast, modelled his first international trip on the European Romantic tradition of the Grand Tour, taking in Rome and Florence. It was in Europe that Inness encountered the works of the Swedish scientist and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, whose idiosyncratic philosophies would change the way Inness saw the world and make a lasting impact on his work. Inness was a religious man, once stating that "theology is the only thing except art that interests me". However, his faith is not necessarily inscribed in his work: unlike the painter William Page and the sculptor Hiram Powers, both of whom were followers of Swedenborg, Inness, according to one critic of the era, Charles de Kay, "does not express [his religion] but hides it in his art".

Inness was known as a contrarian, and it is believed that his 1851 trip to Italy was cut short due to an altercation with a guard at an assembly with the pope in the Piazza of San Pietro. According to a contemporary story in the Boston Transcript, "[a] French officer standing near Inness ordered him to take his hat off, to which he rapped the man in the epaulettes over the head; whereupon there was a terrible commotion among the soldiers...[they] took the little artist into custody, and carried him off to jail." He was soon set free, but it is thought he may have been expelled from Italy.

In 1853 Inness returned to Europe, this time visiting Paris, where he encountered the emerging movement of French Realism: the work of Gustave Courbet et al. At the Paris Salon he was inspired by the work of Théodore Rousseau, drawn, as Adrienne Baxter Bell notes, "to the fresh, loose brushwork and overt emotional tenor of Barbizon paintings".

Inness's itinerant lifestyle moved in parallel with his personal life. He was unsettled, often ill, and prone to depressive mood swings. He could be cantankerous and had a reputation for throwing people out of his studio for asking stupid questions. His movement away from the Hudson River Valley as a child, and as an adult away from North America entirely, symbolized his emotional movement away from contemporary American artistic milieux. During his mature period he became increasingly estranged from denizens of the Hudson River School such as Jasper Francis Cropsey, Sanford Robinson Gifford and Frederic Edwin Church's. In the words of the mid-twentieth-century critic and curator Nicolai Cikovsky Jr., "[w]herever his contemporaries were going, he was going the other way." Inness's fascination with the European tradition was out of kilter with the pioneering and nativist, though admittedly still European-influenced, spirit of nineteenth-century American painting. "Studying the old masters", Cikovsky notes, "was one of the worst things an American artist could do. It was the surest way to compromise one's nationality".

The critics often agreed. Early in his career Inness was lambasted for being overly fascinated with the Old Masters, with one commentator describing his pictures as "shallow affectations of that which is at best superficial to art - the accomplishment, not the subject." Inness was advised to curb his enthusiasm for the European tradition and to depict what he saw in nature instead. While everyone around him - Thomas Moran, Asher B. Durand and friends - was depicting the grandeur and majesty of the American wilderness, Inness wanted to depict the way man made his mark on nature. As curator Margi Conrad explains, "[i]nstead of minute fidelity to the facts of nature, he focused on the emotions the landscape evoked through the use of indefinite forms and suggestive color."

In 1853 Inness was elected to the National Academy of Design as an associate - most of his Hudson River School contemporaries had already been given full membership, a privilege which would not be extended to Inness until 1868. During the mid-1850s he returned Europe, this time visiting London and Amsterdam, where he was inspired by the work of Meindert Hobbema at the Rijksmuseum.

In 1855 Inness produced a series of canvases clearly influenced by the Barbizon School which, though modern in both style and intention, continued to disappoint critics in the United States. One found it "scarcely credible that an artist who is possessed of undoubted talents, and who has produced fine works, should so prostitute his ability to paint like this."

Five years later Inness moved to the village of Medfield in Massachusetts in a bid to improve his health. He was frail, suffering from epilepsy, and dogged by stress and anxiety due to his poor critical reception and accompanying financial insecurity. Here he began to work in the style of the Dutch landscape painters and honed the influence of the Barbizon School. According to Baxter Bell, "Inness felt a particular kinship with [Théodore] Rousseau, for both artists held that an immaterial, even supernatural force generated all forms of life."

Late Period

Inness's fortunes changed just as first generation of the Hudson River School began to disband, but it was the Civil War rather than the waning of the Hudson River flame that seemed to change everything for Inness. An ardent abolitionist, he tried to enlist, but failed the medical. Instead he banged the drum for the cause, organizing rallies, giving speeches, and trying to encourage volunteers and donations. As public opinion on this issue shifted Inness's work seemed to become more palatable: people at last understood it was intended to be interpretive rather than descriptive. According to Cikovsky, the two facts were related: "[t]he tensions of war created an emotional climate sensitive to his expressive style." By the end of the 1860s critics began to see Inness in a new light, with one naming him a "man of unquestionable genius."

In 1863 Inness became a drawing instructor, teaching the Art Nouveau designer Louis Comfort Tiffany and the landscape painter Carleton Wiggins. Five years later, Inness and his wife Elizabeth were baptized in the Swedenborgian New Church in Brooklyn.

In 1870 Inness returned again to Europe, this time staying for four years. He lived in Rome, creating a series of landscape paintings before moving to Normandy in 1874. (He attended the first Impressionist exhibition in Paris at the time, but was unmoved, describing the style as a "sham" and a "passing fad".) Returning to the States, he settled in Boston.

It was not until his final decade that Inness began to really prosper from his art. In December 1884 he brought an estate in Montclair, New Jersey and moved there permanently. He continued to work prolifically and travelled widely well into his sixties. During the last ten years of his life he visited the Adirondacks, Niagara Falls, Nantucket, Virginia, Georgia, Chicago, California, Montreal, and England. Baxter Bell notes that "[t]he unbridled energy that fueled these trips is evident in the many accounts of Inness at work in his studio, which often focus on his physical engagement with the process of painting."

Inness had at last found contentment, but good health still eluded him, and he suffered from dyspepsia and rheumatism. Friends also continued to be concerned by his bouts of depression; he could be melancholic and was reported to have attempted suicide. An early biography stated that he was once found in his studio "slowly bleeding to death from an artery he had opened in his arm on one of those days when life seemed too dark to endure."

By the end of his life Inness had won national acclaim, enjoying (or enduring) the accolade of "America's greatest living landscape artist." Baxter Bell described Inness as the "leading American artist-philosopher of his generation" in reference to spiritual and philosophical basis of his work.

Inness died suddenly of a heart attack in 1894 while on a trip to Scotland at the age of 69. His son reported that he was watching the sun set when he threw his arms in the air, proclaimed "My God! oh, how beautiful!", and fell to the ground. His body was returned to America where it lay in state at the National Academy of Design. According to Cikovsky, "[w]hen Inness died, he was in the public eye and his paintings had for a long time epitomized American artistic understanding and sensibility." He had created around 1,150 paintings, watercolors, and sketches.

The Legacy of George Inness

At the time of his death, Inness was known as "the father of American landscape painting". He left behind a son, George Inness Jr, who followed in his father's steps and became a painter, as well as his son-in-law, Jonathan Scott Hartley, who became a sculptor.

Though not a modern artist in the sense that we usually understand the term, George Inness' work certainly provoked strong reactions and intense debate in his lifetime. As the art historian Andrew Butterfield notes, "[e]ven at the height of his fame during the late nineteenth century, his landscape pictures disgusted some viewers, while moving others to rapturous praise." His critics called his paintings "diseased" and "perverted"; one reviewer in The New York Times in 1878 speculated that Inness might be insane.

Inness's expressionistic approach to depicting landscapes was at odds with the implied fidelity to nature of the Hudson River School, leading to comparisons with the English Romantic painter J.M.W. Turner. But these were vehemently rejected by Inness, who described Turner's groundbreaking Slave Ship as "the most infernal piece of clap-trap ever painted. There is nothing in it." In general he spurned comparisons to other artists: fiercely independent both professionally and personally, he preferred to forge his own path.

It was only in Inness's later years that critics really began to understand his influence on art, whether in paving the way for Tonalism, or in aligning the interests of the French Impressionists - whom Inness, of course, scorned - with the march of American Art. This combination of influences would inspire artists such as Joseph Decker and, in his later work, William Keith. Inness was also admired by African American artist Charles White, who studied Inness' landscapes at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Recent decades have seen a new appetite for Inness's work, with exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art, the Newark Museum, the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, and the National Academy of Design in 2003.

Influences and Connections

-

![Theodore Rousseau]() Theodore Rousseau

Theodore Rousseau -

![Claude Lorrain]() Claude Lorrain

Claude Lorrain -

![Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot]() Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot ![Charles-François Daubigny]() Charles-François Daubigny

Charles-François Daubigny- Salvator Rosa

- Régis-François Gignoux

- John Jesse Barker

-

![The Barbizon School]() The Barbizon School

The Barbizon School - American Landscape Painting

- Dutch Landscape Painting

-

![Louis Comfort Tiffany]() Louis Comfort Tiffany

Louis Comfort Tiffany - Carleton Wiggins

- Joseph Decker

- William Keith

- George Inness Jr

- Jonathan Scott Hartley

Useful Resources on George Inness

- A History of American Tonalism: Crucible of American ModernismBy David Adams Cleveland

- George InnessOur PickBy Nicolai Cikovsky Jr. and Michael Quick

- George Inness: A Catalogue RaisonnéBy Michael Quick

- George Inness and the Science of LandscapeBy Rachael Ziady DeLue

- George Inness and the Visionary LandscapeOur PickBy Adrienne Baxter Bell

- George Inness in Italyby Mark D. Mitchell and Judy Dion

- George Inness: The Man and His Art (Classic Reprint)By Elliot Dangerfield

- George Inness: Writings and reflections on art and philosophyOur PickEdited by Adrienne Baxter Bell