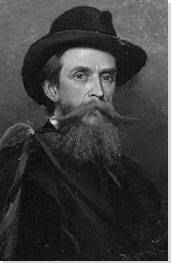

Summary of Thomas Moran

Thomas Moran was one of the most significant North-American painters of the nineteenth century. He was part of the second generation of great US landscape painters, who took the signature style of spiritually-infused naturalism developed by pioneers such as Thomas Cole and adapted it to new vistas. But whereas followers of Cole such as Frederic Edwin Church had fixed the quixotic gaze of the colonial artist on the Andes of South America, Moran's attention was drawn westwards, to the expanses of the Rocky Mountains and Yellowstone National Park. Painting in a style that arguably surpassed both Cole and Church for divine yet naturalistic grandeur - his seas and skies have something of the Sublime quality of J.M.W. Turner - he opened up a whole new portion of the North American landscape to the imagination of its settler community.

Accomplishments

- Thomas Moran is often said to form part of the Rocky Mountain School. Though not a 'school' in any conventional sense, he was one of a number of artists (including Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Hill, and William Keith) who developed the aesthetic of the East Coast-based Hudson River painters by depicting the vaster, more rugged terrains of the American West. A direct thread can be traced back from their work to the adapted European-Romantic aesthetic of Cole et al. Indeed, in the case of Bierstadt, Keith, and the English-born Moran, combined European and American identity perhaps enhanced the Northern-European Romantic aesthetic underlying their work.

- J.M.W Turner's work was an exemplar to many of Moran's contemporaries. But perhaps no North-American landscape painter of the nineteenth century inherited the mantle of Turner's rugged magnificence like Moran. The combined qualities of Sublimity and apparent rootedness in human emotion that define Moran's best canvases - less glossy and overdone than some of his contemporaries' - arguably position him as Turner's most important North-American protégé.

- Moran's work exemplifies the quality of the Sublime in art, whereby grand natural spectacles - or sometimes manmade ones - generate a sense of terror and awe in the viewer. The Grand Canyon and other landmarks of the American West appear so vast and alien in his work that they seem somehow impervious to the scales of human experience and emotion. This was a quality that Moran and other American landscape painters borrowed directly from European predecessors of the eighteenth century, such as the dramatic painter Caspar David Friedrich.

- Moran's depictions of the American West have a complicated legacy in national popular culture. While he opened up these landscapes to the tourist industry that would (practically) overrun them, his work has also been vital to ongoing attempts to preserve them. His paintings of Yellowstone, for example, were pivotal in ensuring that Congress established the area as a national park. Today, his paintings continue to inspire the American public to seek out the ever-diminishing rugged spaces of their nation.

Important Art by Thomas Moran

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone

This enormous canvas displays Moran's skill as a colorist, but also shows his ability to combine topography with myth. The composition is divided by a vast V shape, as the Yellowstone River scores the rocky landscape, evoking a strong sense of the primordial. It is picked out in a vibrant blue, which contrasts with the earthy greens, browns and ochres of the surrounding landscape. The river, though dwarfed by the mass of the landscape, asserts its own power as its shape dictates the very composition of the work. Shafts of light pour down opposite sides of the gulf, drawing attention to the rocks' strata and characteristics. Firs and pines extend vertically, drawing the eye heavenwards, while in the lower foreground, a party of Native Americans provide the only witness to this scene of desolate splendor.

Like many of Moran's canvases, the work combines his naturalist's eye for detail with a strong sense of the divine. The artist himself summed up these combined impulses as follows: "[b]y all artists, it has heretofore been deemed next to impossible to make good picture of Strange and Wonderful Scenes in nature; and that the most that could be done with such material was to give topographical or geologic characteristics. But I have always held that the Grandest, Most Beautiful, or Wonderful in Nature, would, in capable hands, make the grandest, most beautiful, or wonderful pictures, and that the business of a great painter should be the representations of great scenes in Nature." The greatness of this scene was enhanced by its scale: at 7-by-12 foot, The Grand Canyon was the largest painting Moran had ever produced, and he affectionately called it his 'big picture'.

When this piece was presented to the public, it provided many with their first view of the national wonders of the Yellowstone. The Grand Canyon has since become such an iconic part of American cultural identity that it is difficult to imagine the effect that its 'discovery' must have had (though of course, the figures in the lower foreground remind us that European settlers were not the first to view it). The work, which took six years to complete, was hailed a masterpiece, and the federal government paid $10,000 for it and hung it in the Capitol. A review at the time, by the poet and editor Richard Watson Gilder, declared it "[t]he most remarkable work of art which has been exhibited in this country for a long time." Its success was instrumental in launching Moran's career in art.

Oil on canvas mounted on aluminum - Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

The Chasm of the Colorado

The focus of this work is simultaneously on the rocky solidity of the American landscape and on the void which encompasses it. Literally, the work centers on a vast yawning gulf that sucks in light, life and water, at the bottom of which the tiny Colorado River snakes. Symbolically, The Chasm of the Colorado poses important questions about the nature of the landscape over which the United States had transposed its notions of civilization. The uninhabited scene has an almost apocalyptic atmosphere, suggesting some form of resistance or recalcitrance to the values inscribed in the painter's strokes. The snake in the foreground, meanwhile, adds a tincture of Biblical allegory to the composition.

Following in the tradition of European predecessors such as Casper David Friedrich, Moran is grappling here with the notion of the Sublime: with the idea that a natural landscape might embody qualities of beauty at once awe-inspiring and terrifying to the viewer, because they represented forces impervious to the scales of human existence. In this scene, that feeling is intensified by the complete absence of human life, and by our placement as viewers precipitously high up, almost level with the clouds. The work was in fact painted from this vantage point, at Powell's Plateau, a northwest summit of the Grand Canyon. Despite its equivocal gaze on the wilderness, this work would take on an ironically pivotal role in advertising the region to tourists, and it was reproduced repeatedly in magazines, posters and guidebooks. Like its predecessor, it was also commercially successfully, purchased by Congress for $10,000, to be hung in the Capitol opposite The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone.

The work reception was more mixed amongst the American critical community, perhaps more alert to the implicit sense of dread it conveys. Poet and editor Richard Watson Gilder wrote: "[i]t is awful. The spectator longs for rest, repose and comfort...The long vista of the distant table-land suggests a sunny place of refuge from all this chaos and tumult. But for the rest there is only an oppressive wildness that weighs down the senses. You perceive that terror has invaded the sky." Journalist Clarence Cook meanwhile, likened the work to a vision of Dante's inferno. Contemporary responses to the work tend to emphasize its unique value within Moran's oeuvre, as exemplified by Joni Louise Kinsey's summary: "The Chasm of the Colorado is a richly complex and profoundly evocative work of art that requires a comprehensive interpretation of its formal qualities, technical manipulations, and inextricable connection to the social, cultural and philosophical currents of its time. An awareness of its multidimensional meanings promotes a new respect for Moran as an artist of undeniable sensitivity to the visual world and to the world of ideas, elevating the work itself far above the level of simply another grand landscape with national significance."

Oil on canvas mounted on aluminum - Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

Fiercely the Red Sun Descending Burned His Way Along the Heavens

This work is one of a number presenting scenes from the south shore of Lake Superior, the largest of North America's Great Lakes. Following an approach developed by Claude Lorrain, and later associated with J.M.W Turner, most of the composition is taken up by the vast, low-hanging sky, filled with volcanic reds, oranges and yellows. The sun lights up the water-vapor in the atmosphere as if turning it to fire, a shocking hue reflected in turn on the thick, dark waves below. Emerging from this scene is an archway of rock, framed all around by water and mist. The arch would become an important motif for Moran, who sought to reference classical European art and architecture in his depictions of the strange New World.

The work takes its title from a poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, whose writing was in turn inspired by Moran. But the painting primarily pays tribute to Moran's idol JMW Turner, particularly his 1840 work Slave Ship (Slaves Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On). Turner's dynamic and troubling work is similarly afire with reds and oranges, a violent scene at once honoring the awesome power of nature and drawing attention to the evils of the slave trade. Moran produced an engraving of a similar subject in 1873, in which a man appears to be drowning at the base of the arch while a distant ship pitches in a violent sea. But in this later work, Moran's subject is the terrifying vengeance of God rather than the evils of humankind. The curator John Coffey sums up something of the impression of impending doom or cataclysm that it evokes: "Moran uses light to corrode landscape and dissolve it. You feel like the world is slipping away."

In art-historical terms, this is a work that seems at once to look forwards and back. On the one hand, not only is its debt to Turner evident in every brushstroke, but the presence of the arch seems to ground the scene in an earlier, European classical notion of mythological narrative and judgement. As Joni Kinsey explains, "[h]is affinity with such features...reveals that he, like his literary counterparts, was creating American analogies to grand historical landscapes because they alluded to the mysteries of creation." At the same time, Moran's wild seascape alludes in its tonal palette to contemporary developments in North-American Luminism, while its expressive (non-Luminist) brushstrokes evoke, perhaps unwittingly, the emergence of Impressionism in Europe across the preceding decade.

Oil on canvas - North Carolina Museum of Art

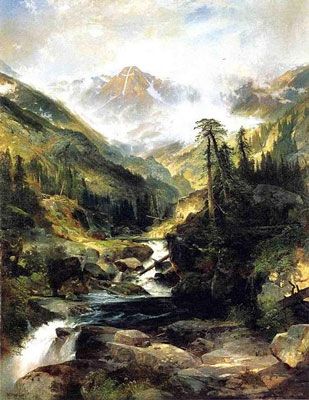

The Mountain of the Holy Cross

In this work depicting the glacial cruciforms beyond Gray's Peak in the Rocky Mountains, the imagined viewer is situated at the bottom of a mountain river whose strength and power is referenced in the tree trunks left vertical or upended upstream, felled by the water's currents. The lower two thirds of the canvas are dark, gloomy and damp, taken up by the zig-zagging valley, rocks and trees. The movement of the river leads the eye up to the small rock face in the center top, which provides the symbolic crux of the work. Shrouded by mist and snow, it clearly shows the geological feature from which the work takes its name. Two cleaves in the rock have left an enormous cruciform shape, filled with the snow and ice of glacial deposit.

The Mountain of the Holy Cross was an important landmark for pioneering settlers, unknown to topographical study until 1873, when the explorer and geologist Ferdinand Hayden published photographs of the area. One of Moran's more difficult expeditions, reaching the viewing plateau from which this work was created meant ascending 12,000 feet of treacherous and slippery mountainside on the Rockies' Sawatch Range. Witnesses had recounted that the cross would disappear on their approach, and the strangeness of this geographical formation added to its mystery and allure. Moran meant the work to be a nationalistic image, as he projected Christian doctrine onto this natural scene; the canvas became Moran's chief contribution to the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876.

Moran wanted this work to form a triptych with The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone and The Chasm of the Colorado but due to a disagreement at Congress, the three have never been hung together. It did however help to promote the area's popularity, and after the turn of the century the Mountain of the Holy Cross became a popular pilgrimage site, and an important destination for health tourism. Moran's work also inspired poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to write an elegy to his late wife entitled A Cross of Snow.

Oil on canvas - Museum of the American West, Autry National Center, Los Angeles, California

The Three Tetons

Once again, Moran's subject is the splendor of the Rocky Mountains, specifically the distinctive Three Tetons, the principle summits of the Wyoming Range. Despite the distant presence of the jagged peaks, however, the bed of grasses and prairie wildflowers in the foreground contributes to a lighter, more 'pastoral' mood than is achieved in many of his previous works. This is enhanced by the presence of roaming cattle, and a small encampment: here is a Moran landscape which, for once, seems fit for human habitation. Thus, while the work cannot exactly be called picturesque, it certainly strikes a less foreboding note than its predecessors. The viewer's eye is gradually drawn upwards to the snow-capped mountains in the mid- and background, but the white-cloudy sky above seems to subdue the impression of sublimity and terror which they might otherwise evoke.

Between August 21 and August 29, 1879, Moran attempted to cross the Snake River Valley running across Idaho and Wyoming, escorted by Captain Augustus Bainbridge along with a group of soldiers and Native American scouts. Though the expedition was ultimately unsuccessful, it afforded Moran memorable glimpses of the Tetons, which, as he wrote in his diary at the time, "loomed up grandly against the sky. From this point it is perhaps the finest pictorial range in the United States or even N. America." Later the same day he wrote: "we made sketches of the Teton Range but the distance, 20 miles, is rather too far to distinguish the details, especially as it is very smoky from fires in the mountains on each side of the peaks." Moran would never make it to the view the Tetons up close, though the pages from his diary which might explain why the mission was aborted have been mysteriously removed. This may explain why this work, measuring just 50 by 64 cm, strikes such a subdued and peaceful tone as compared to those works which depict the landmarks of the North-American wilderness close up.

Despite their diminutive scale, Moran's images of the Tetons captured the public and critical imagination. Notably, they caught the attention of the influential British art critic John Ruskin, who said of Moran: "[n]or are there any descriptions of the Valley of Diamonds, or the Lake of the Black Islands, in the 'Arabian Nights,' anything like so wonderful as the scenes of California and the Rocky Mountains which you may ... see represented with most sincere and passionate enthusiasm by the American landscape painter, Mr Thomas Moran." A mountain in the Teton Range is named Mount Moran in the painter's honor.

Oil on board - The Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa

Grand Canyon (From Hermit Rim Road)

If Moran's earlier canvases depicting the Grand Canyon convey a sense of distance and scale, this work might be said to express a sense of depth. Divided diagonally from the top right to the bottom left, it features an array of greens and grays in the foreground, the pines and rocks of the area represented - for the most part - with Moran's famous scientific accuracy. In the middle of the canvas, however, the landscape drops away, revealing the vast depths of the Canyon in a manner which is almost literally vertiginous. The left diagonal section of the work is rendered in blues, purples and grays, as if the sky itself were leaching into the Canyon, through which the distant Colorado River snakes.

The Grand Canyon was Moran's preeminent subject-matter, one he was drawn to again and again throughout his career. "Its tremendous architecture", he wrote, "fills one with wonder and admiration, and its color, forms and atmosphere are so ravishingly beautiful that, however well-traveled one may be, a new world is opened to him when he gazes into the Grand Canyon of Arizona." Moran was also fascinated by the indigenous flora of the area, which he described as "weird in the extreme". Some of the trees in the foreground of this work have particular significance, however. In this and other works he would add European trees and foliage to his scenes, many of them based on his travels around Italy, in an attempt to synthesize the landscapes of the old and new worlds. As Joni Kinsey notes, "[i]t was in the monumental vistas of the West that the United States could rival the great artistic subjects and achievements of the Old World, and it was through these scenes that America could claim distinction and even superiority to them."

This work, created as Moran approached the final decade of his life, sums up many of his most notable achievements as a draftsman. The early-twentieth-century critic Wolfgang Born lauded his mastery of the "panoramic style", noting that "[h]is feeling is akin to [that of] men who covered the ceiling of Baroque churches with illusionistic frescoes - only they raised their eyes to the heights of the sky, whereas Moran, placing his easel on a choice observation point, looked down into the crevices of the earth." More recently, the art historian Alexis Drahos has described Moran as the last great nineteenth-century American painter to depict the landscape with a scientist's eye for detail: "[h]is vast landscapes are imbued with Earth science, just like those of his forerunners Thomas Cole and Edwin Church. While continuing a great tradition into the final years of the 19th Century, he also brought about its closure."

Oil on canvas - The Santa Fe Collection of Southwestern Art, Chicago

Biography of Thomas Moran

Childhood and Education

Thomas Moran was born on February 12th, 1837 in Bolton, Lancashire, in the English industrial heartland which was also the childhood home of America's pioneer landscape painter Thomas Cole. Born to Mary (née Higson) and Thomas Moran Senior, Moran was one of seven children. He came from a line of handloom weavers, whose skills were made redundant with the invention of power looms.

Moran's early years were a time of financial stress for his family. According to his biographer Thurman Wilkins, Moran's father wanted a future for his children "free of the shackles of British class distinction and the starvation of being a handloom weaver". Enticed by the promise and economic opportunity of the new world, in 1844 he moved the family to America. The crossing made an impression on the seven-year-old Moran, and he spent hours watching the waves, from which he later produced sketches and paintings of the ocean.

The family moved first to Baltimore then settled in Kensington, a suburb of Philadelphia, where they found themselves at the center of a community of immigrant textile workers. Even as a child, Moran was drawn to art, and would regularly visit galleries and exhibitions, gaining an appreciation for a wide range of painting styles.

Early Training and Work

By the age of 16, according to his biographer, Moran had become a "prepossessing youth with gray-blue eyes, high forehead and light brown hair". He began an apprenticeship at the Philadelphia engraving firm Scattergood and Telfer, thus becoming one of a number of American landscape painters, including Asher B. Durand, John F. Kensett, John William Casilear and George Inness, who began their professional life as engravers.

According to Wilkins, "Moran filled his free daylight hours with painting in watercolors and his evenings with drawing by gaslight in black and white, when working in color was less feasible. Absorbed in a practice that would develop into a regular pattern, he began to reach the shop later in the mornings and to leave earlier in the afternoons." This early informal training would prove invaluable to him, and Moran remained largely self-taught throughout his life.

After three years at Scattergood and Telfer, he abandoned his apprenticeship. He was drawn to the studio of his older brother Edward, already on his way to becoming a respected marine painter. Here, Moran met the well-known Philadelphia painter James Hamilton, the man dubbed the "American Turner", who would became his mentor.

According to Wilkins, "Moran was never avant-garde. Coming to maturity at a time when British tradition was still a force in American art, he trained, indeed steeped himself in that tradition." Moran was particularly fascinated by the work of J.M.W. Turner, and spent years studying reproductions of his work. In 1861 he travelled with his brother to London, where they spent months studying and copying Turner's canvases at the National Gallery.

Moran was lucky enough to come to maturity at a time when Romantic landscape painting had become a potentially lucrative venture. But he was also very hardworking. As a young man he would work 13 hours a day in his studio, a routine he would maintain throughout his life. Inspired by English Romanticism, Moran chose to ignore most contemporary developments in European Modernism, such as the birth of Impressionism during the 1860. He was, however, inspired by the work of the English Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a cousin of the European Symbolist movement. He was also influenced by the Victorian art critic John Ruskin, particularly by his concept of "truth to nature", which proposed that the artist had a fundamental role connecting nature and society.

In 1857 Moran met Mary Nimmo, who later became his wife. After their marriage in 1863, the Scottish-born Nimmo began teaching herself to sketch and paint, and became a skillful artist in her own right. Their son Paul was born in 1864, followed by two daughters, Mary and Ruth. The couple were happy and well-matched, as their daughter Ruth recalled: "[i]n their home there was always music and laughter. Working through the evening as well as most of the day, they still had time for their friends." The family spent some time in France, but Moran was unimpressed with the landscape painting he found there, in spite of the country's rich artistic heritage. He would later state: "French art, in my opinion, scarcely rises to the dignity of the landscape." They also travelled through Italy and Switzerland, before returning to America, where they settled in New Jersey.

Mature Period

Moran was a member of the Hudson River School, a group consisting of several generations of American landscape painters who worked between 1825 and around 1870. The name was applied retrospectively, and referred mainly to the distinct subject-matter and aesthetics of a particular group rather than their confinement to one geographical location. That said, the school's early leaders, such as Thomas Doughty, Asher Durand, and, above all, Thomas Cole, were best known for representing the landscapes of the Hudson River Valley in upstate New York. The school grew largely out of the European Romantic movement, but it also had a strongly nationalistic bent, focusing on the sublime beauty of the American wilderness. Besides becoming an important painter associated with the "second generation" of the School, Moran enjoyed a successful career as an illustrator. Between 1870 and 1885 he is thought to have produced more than a thousand published commercial images and engravings, primarily to fund his frequent trips into the wilderness.

Moran's inquisitive and adventurous nature increasingly led him westwards, away from the spiritual home of the Hudson River School, for which reason he is also remembered, along with Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Hill, and William Keith, as a member of the so-called Rocky Mountain School. The painters of this school applied the luminous color palette and European Romantic aesthetics of the Hudson River School to the landscapes of the American West.

His emergence as one of the leading exponents of this school was partly fortuitous. In 1870, while still in his early thirties, Moran was asked by Scribner's Magazine to rework sketches of Yellowstone National Park made by a member of an expedition party. Moran was so inspired by the prospect that he borrowed the necessary funds to make the trip himself. Though he had never previously ridden a horse or spent a night under the stars, the following year he spent forty days traveling through Yellowstone with the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, as part of the Ferdinand Hayden survey. He documented over 30 sites, and legend has it that he became so thin that he had to travel with a cushion on his saddle to protect his bony bottom.

He kept a detailed diary during his trip, which, though not creatively inspired, reveals his sense of exhilaration and freedom: "[a]fter descending to the shore of the lake, some of the party fished in it and caught a few of the finest trout that I have yet seen...Made a large fire and cooked our supper of black tailed deer meat, which I enjoyed hugely after riding and nearly all day. For the first time in my life I slept out in the open air during the night. It rained a little but not enough to wet us to any extent." The Yellowstone trip marked a turning point in Moran's career. Exploratory trips across the American continent would shape the rest of his working life. He became so attached to the West that he was known as Thomas "Yellowstone" Moran.

Two years later Moran made his first trip to the Grand Canyon, with John Wesley Powell's government survey. The following year he explored the Mountain of the Holy Cross, a prominent summit in the northern Sawatch Range of the Rocky Mountains that had only been officially "discovered" the previous year. The mountain took its name from the cruciform shape of the snow-patch on its rocky face. He would use sketches and watercolors created en route to work from later in his studio. The oil paintings produced from these trips are now thought of as archetypes of American Landscape paintings.

Once his status allowed him to do so, Moran began to visit the English critic John Ruskin, whose writing had greatly influenced him, to show him his work. In a profile of the artist in The American Magazine in 1913, it was reported that "[w]hen Thomas Moran visited John Ruskin, that great but eccentric critic, and showed him a sketch of the 'Bad Lands' of Utah, Ruskin exclaimed, 'What a horrible place to live in!' 'Oh', replied Moran, with a twinkle in his eye, 'we do not live there. Our country is so vast that we keep such places for scenic purposes only'." The magazine also reported that when Moran showed him a sketch of the Grand Canyon, he had to convince the critic it was not the work of Turner.

In 1882, Moran designed and built his family home in the Hamptons, without the help of an architect. The couple covered the walls with art and curiosities they had collected from their travels. The house has been preserved, and stands now as a tribute to the couple's work. The building, on East Hampton's Main Street, was nearly destroyed by the 2012 Hurricane Sandy, but has since been repaired and restored.

The art historian Joni Kinsey states, "[b]y the end of the nineteenth century, his landscape views, especially those of Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon, were recognized as the definitive treatments of those natural wonders. His work, then as now, was seen as both accurate and eloquent, with the sense of place conveyed as much by its spirit as by its appearance". Moran's work made him rich, and he was able to travel extensively throughout the landscape that captured his imagination right up until the end of his life.

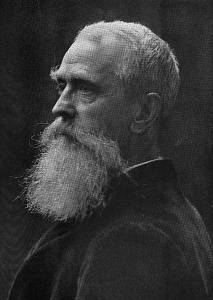

Late Period

Moran's love affair with the art of Turner took him across the world during the later decades of his career, as he followed the path taken by his idol. In 1883 he visited Mexico, and spent time touring the Grand Canyon and New Mexico. In 1899, Moran was devastated by the death Mary at the age of 47. She had contracted typhoid fever after nursing her daughter Ruth through the disease. Two weeks later he left the family home to lead an itinerant life for the following 17 years. He settled in Santa Barbara in the early 1920s with Ruth, remaining there for the rest of his life. He made his final journey to Yellowstone in the 1920s, at the age of 87.

Moran worked right up the end of his life, creating more than 1500 oil paintings and 800 watercolors across the course of his career. He died in 1926 at the age of 89 in Santa Barbara, California, and was memorialized as both the "the last of America's romantic painters" and the "Dean of American Landscape Painters." His daughter Ruth described him as "a romantic figure, in a not very romantic period. He was quick-witted, full of humor, kind and generous; but quick-tempered, also, and a good fighter for any cause that he might take up." The artist's legacy lives on at his East Hampton home, the Thomas and Mary Nimmo Moran Studio, while Mount Moran in the Grand Teton National Park was named in his honor.

The Legacy of Thomas Moran

Like his predecessors Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, Moran was steeped in the traditions of European Romantic painting, but he also believed that American art needed to find its own, native subject-matter. Believing that artists owed it to the American wilderness to depict its beauty for posterity, his work became integral to the protection of the areas he loved. His paintings of Yellowstone, for example, proved essential in convincing the United States Congress to establish the area as a National Park.

In artistic terms, Moran's significance perhaps resides in his work's capacity to outlive the trends that inspired it. The artist Arthur Millier once described Moran as "an 'old master' not incomparable with Turner and Claude Lorrain", whose work "did not 'date' in quite the same manner as, for instance, Albert Bierstadt. There was an imaginative element in his work that was able to transcend a style of painting itself successively outmoded by the Barbizon, Impressionist, and finally the hydra-headed Post-Impressionist importations."

As regards specific threads of influence, Moran's work notably went on to inspire members of Group f/64 and especially Ansel Adams. The most important American landscape photographer of the twentieth century, Adams was a nature-lover like Moran, and his work has taken on an equally integral role in campaigns to conserve the American landscape.

But perhaps above all else, Moran's significance lies in the capacity of his work to influence popular consciousness, and the American nation's sense of itself. As the critic Joni Kinsey states, "[i]n making remote and mysterious regions accessible to the American public through paintings, drawings and illustrations, he influenced an entire generation's understanding of its country. Thomas Moran provided his viewers with a visual sense of place, thus contributing to making the West an indelible part of the American consciousness." For writer Robert Allerton Parker, Moran's "expression has passed into our very culture. Perhaps more than any other American painter of the latter half of the nineteenth century, Thomas Moran compelled the American people to appreciate the beauty of its own continent."

Influences and Connections

-

![Thomas Eakins]() Thomas Eakins

Thomas Eakins - James Hamilton

- Edward Moran

- Thomas Hill

- William Keith

-

![Ansel Adams]() Ansel Adams

Ansel Adams - Gustave Buek

- William Robinson Leigh

- Edward Percy Moran

- Jean Leon Gerome Ferris

- Thomas Hill

- William Keith

-

![Luminism]() Luminism

Luminism -

![Tonalism]() Tonalism

Tonalism -

![Group f/64]() Group f/64

Group f/64 -

![American Regionalism]() American Regionalism

American Regionalism - The Rocky Mountain School